Abstract

Poly-N-acetyllactosamine extensions on N- and O-linked glycans are increasingly recognized as biologically important structural features, but access to these structures has not been widely available. Here, we report a detailed substrate specificity and catalytic efficiency of the bacterial β3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (β3GlcNAcT) from Helicobacter pylori that can be adapted to the synthesis of a rich diversity of glycans with poly-LacNAc extensions. This glycosyltransferase has surprisingly broad acceptor specificity toward type-1, -2, -3 and -4 galactoside motifs on both linear and branched glycans, found commonly on N-linked, O-linked and I-antigen glycans. This finding enables the production of complex ligands for glycan-binding studies. Although the enzyme shows preferential activity for type 2 (Galβ1-4GlcNAc) acceptors, it is capable of transferring N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) in β1-3 linkage to type-1 (Galβ1-3GlcNAc) or type-3/4 (Galβ1-3GalNAcα/β) sequences. Thus, by alternating the use of the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT with galactosyltransferases that make the β1-4 or β1-3 linkages, various N-linked, O-linked and I-antigen acceptors could be elongated with type-2 and type-1 LacNAc repeats. Finally, one-pot incubation of di-LacNAc biantennary N-glycopeptide with the β3GlcNAcT and GalT-1 in the presence of uridine diphosphate (UDP)-GlcNAc and UDP-Gal, yielded products with 15 additional LacNAc units on the precursor, which was seen as a series of sequential ion peaks representing alternative additions of GlcNAc and Gal residues, on matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) analysis. Overall, our data demonstrate a broader substrate specificity for the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT than previously recognized and demonstrate its ability as a potent resource for preparative chemo-enzymatic synthesis of complex glycans.

Keywords: acceptor specificity, β3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, chemo-enzymatic synthesis, glycopeptides and glycolipids, polylactosaminoglycan

Introduction

Polylactosamines (poly-LacNAc) are a common extension of glycans of cell surface glycolipids and glycoproteins. Although LacNAc (N-acetyllactosamine; LN) extensions of the sequence Galβ1-4GlcNAc (type 2) are the most common form of poly-LacNAc repeats found in glycoconjugates (Niemela et al. 1998; Ujita, McAuliffe, Hindsgaul, et al. 1999; Togayachi et al. 2010), LacNAc repeats with Galβ1-3GlcNAc (type 1) have also been reported in mammals (Holmes 1989; Fan et al. 2008; Lin et al. 2009). LacNAc extensions are present on linear or branched core structures of N- and O-linked glycoproteins (Cummings and Kornfeld 1984; Fukuda et al. 1984, 1986; Wilkins et al. 1996; Ujita et al. 1999; Ujita et al. 2000), glycolipids (Fukuda and Hakomori 1982; Zdebska et al. 1983) and keratan sulfate proteoglycans (Nieduszynski et al. 1990; Greiling 1994). Distal substitutions such as sialylation, fucosylation, sulfation and ABO blood group antigens frequently decorate the poly-LacNAc chains and constitute glycan ligands involved in specific biological activities (Fukuda and Hakomori 1982; Leppanen, Niemela, et al. 1997; Niemela et al. 1998; Chandrasekaran et al. 2008).

Recent studies have shown that the topology induced by a different number of LN repeat units has a significant impact on glycan-binding specificity and the affinity of glycoconjugate ligands to their receptors. For example, T and B cell activation is influenced by the number of LN repeats in glycoconjugates on the immune cell surfaces (Togayachi et al. 2007). Also, in context of malignant cell phenotypes, B16 melanoma cells that expressed sialyl Lewis X on long poly-LacNAc were highly metastatic, while cells expressing even more sialyl Lewis X on short poly-LacNAc were not metastatic (Srinivasan et al. 2009). Changes in binding specificity associated with the number of LN unit repeats also has been well documented for common glycan-binding proteins such as galectins (Stowell et al. 2008; Dennis et al. 2009; Srinivasan et al. 2009; Horlacher et al. 2010), selectins (Renkonen et al. 1997; Renkonen 2000; Leppanen et al. 2002; Mitoma et al. 2003; Nagae et al. 2009; Bateman et al. 2010), as well as the influenza-hemagglutinin receptor (Chandrasekaran et al. 2008; Bateman et al. 2010; Nycholat et al. 2012). These are just examples of varied functions of the roles of poly-LacNAc glycans implicated in cell differentiation, aging, immune response, malignant alteration, metastasis and infections.

Although poly-LacNAc extensions are well documented for their biological significance, they are hard to study because of the difficulty to produce them in quantities needed for detailed biological studies. Efforts to address this problem have focused on enzymatic synthesis of poly-LacNAcs. Eight mammalian enzymes specific for poly-LacNAc extensions on various core elements in different tissues have been identified, cloned and used in synthesis (McAuliffe et al. 1999; Ujita et al. 2000; Korekane et al. 2003; Togayachi et al. 2010), which include β3GnT1–β3GnT8. The differences in substrate specificity and distribution of these enzymes indicate that each β3GlcNAc transferase synthesizes a different glycan type. β3GnT2, β3GnT3 and β3GnT5 have shown catalytic activity for initiation and elongation of poly-LacNAc chains on N-glycan, core 1 O-glycan and glycolipids, respectively (Togayachi et al. 2010). However, the in vitro synthesis of poly-LacNAcs on natural core structures has remained a challenge because the mammalian enzymes are typically specific for glycan class and are not efficient enough for preparative scale synthesis (Seppo et al. 1995; Leppanen, Salminen, et al. 1997). On the other hand, bacterial glycosyltransferases with a broad substrate specificity and high activity are known as powerful tools for preparative synthesis of glycans. Combinations of chemical and enzymatic procedures, using mammalian and bacterial enzymes, have been employed to produce poly-LacNAc backbones on various precursors (Maaheimo et al. 1994, 1995; Renkonen 2000; Naruchi et al. 2006; Vasiliu et al. 2006; Severov et al. 2007; Sauerzapfe et al. 2009; Nycholat et al. 2012). We previously reported the gram-scale productions of linear type 2 poly-LacNAc derivatives using N. meningitides enzymes, LgtA (β3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, β3GlcNAcT) and LgtB-GalE (β4-galactosyltransferase fusion) (Vasiliu et al. 2006). However, this method was less successful with natural branched glycans. Moreover, the LgtA catalytic activity was substantially decreased with increasing the number of LacNAc repeats on linear substrates, which diminished the efficiency of extended LacNAc elongation. Particularly, the β3GlcNAcT, LgtA, did not show catalytic efficiency with branched N-glycan acceptor substrates (Vasiliu et al. 2006) and has not been found to utilize type 1 and type 3 acceptor substrates, limiting its utility.

As an alternative, a β3GlcNAcT from Helicobacter pylori (JHP1032) was identified by an activity screening approach of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis genes, and an insertional inactivation method confirmed that it plays an integral role in making LacNAc in the biosynthesis of LPS in H. pylori (Logan et al. 2005). Sauerzapfe et al. (2009) have recently demonstrated that the β3GlcNAcT in combination with a recombinant human Gal-T1, and uridine diphosphate (UDP)-nucleotide donors, can generate poly-LacNAc extensions on type-2 LacNAc substrates. To better assess the potential of the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT for the synthesis of diverse poly-LacNAc glycans, we performed a detailed substrate specificity analysis for the β3GlcNAcT to evaluate its ability in poly-LacNAc synthesis on various natural N-linked, O-linked and I-antigen glycans other than type 2 LacNAc substrates. The enzyme's ability was then assessed for its utility in the preparative scale synthesis of a series of extended type 1 and type 2 poly-LacNAc elongations on various natural core structures. Our data suggest that the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT is an efficient and flexible enzymatic catalyst for poly-LacNAc synthesis on a diverse range of natural linear and branched glycans.

Results

Acceptor substrate specificity studies

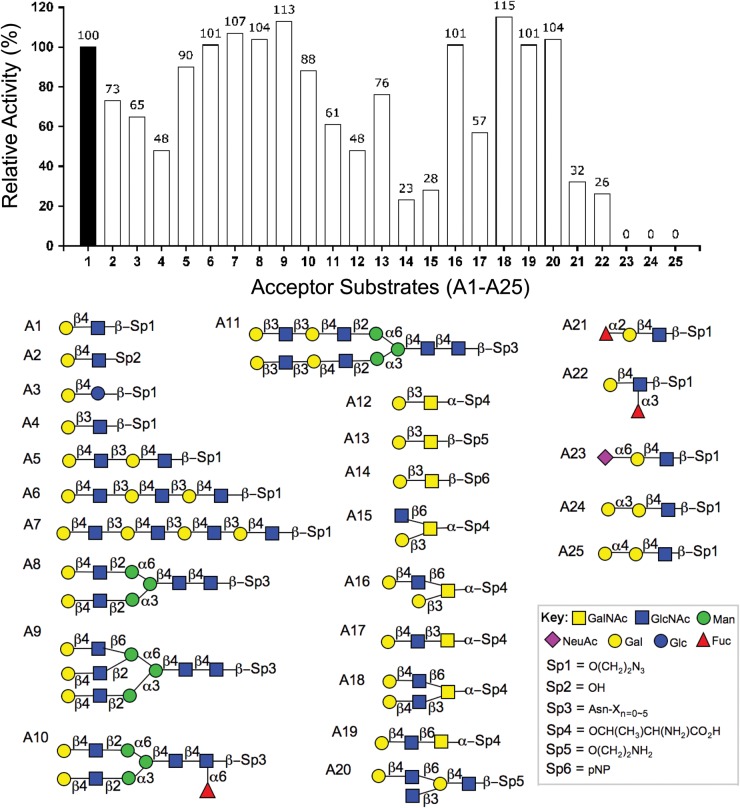

In order to investigate whether the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT can recognize substrates other than linear type 2 LacNAc (Sauerzapfe et al. 2009), we employed a simple assay using UDP-[3H]GlcNAc as a donor to assess the ability of H. pylori β3GlcNAcT to transfer [3H]GlcNAc to 25 different neutral glycans, using separation with an anion Dowex resin to retain the unreacted donor substrate. As shown in Figure 1, nearly all substrates with a terminal Gal residue with a β-linkage to the underlying sugar (A1-A25) exhibited activity, regardless of their penultimate glycan sequence. The best acceptor was the type 2 LacNAc (A1, Galβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp1), exemplified by LacNAc-β-ethylazide used as a positive control (100% activity). Importantly, however, type 1 (A4, Galβ1-3GlcNAc) and type 3 sequence (A12, Galβ1-3GalNAcα-R) and even poor acceptors like the type 4 sequence (A14, Galβ1-3GalNAcβ-R) exhibited a reasonable activity (23%).

Fig. 1.

Substrate specificity of the H. Pylori β3GlcNAcT with panel of acceptor glycans. Relative catalytic activity was determined by the radioactive assay with UDP-[3H]-GlcNAc incorporation onto the acceptor substrates and illustrated in a vertical bar chart. Type 2-LacNAc sp1 as a positive control (100% activity). Reaction conditions are described in Materials and Methods.

Structural features other than the penultimate disaccharide sequence also had little influence on acceptor activity. Extended LacNAc acceptors, i.e. di-LacNAc (A5), tri-LacNAc (A6) and tetra-LacNAc (A7), showed no drop off in activity, demonstrating that the enzyme is useful for the production of extended poly-LacNAc. Transfer to branched bi-antennary (A8), tri-antennary (A9) or core fucosylated bi-antennary (A10) N-glycan acceptors with terminal type 2 LacNAc showed high efficiency, suggesting its utility for the extension of N-linked glycans. Moreover, the enzyme showed ∼60% efficiency with biantennary N-glycopeptide with terminal type 1 LacNAc on each antenna (A11). These results suggested that the β3GlcNAcT would be useful for synthesis of both type 2 and type 1 poly-LacNAc extensions of natural N-glycan derivatives.

The enzyme was also active with type 3 (Galβ1-3GalNAcα-R) and type 4 (Galβ1-3GalNAcβ-R) disaccharides. The efficiency of the β3GlcNAcT with natural core 1, comprising the type 3 structure with α-linkage to Thr, was ∼35% of the LacNAc control (A12). For the type 4 substrates, the enzyme activity varied with the aglycone, ranging from 70% with β-ethylazide (A13) to 20% with, β-p-nitrophenol (A14). Although there was some variation in acceptor specificity, it is important to note that all of the type 3 and type 4 disaccharides were acceptor substrates.

The enzyme was also tested with threonine-conjugated O-glycan cores (cores 2, 3, 4 and 6). Of these, the branched core 2 (Galβ1-3-(GlcNAcβ1-6)GalNAc-α-Thr; A15) sequence contains a single Type 3 galactose that can serve as an acceptor determinant for β3GlcNAcT. For the other cores, prior β4-galactosylation of O-glycans installs a linear or branched type 2 LacNAc sequence that proved to be favorable substrates for the enzyme (A16-A19), yielding 57–115% efficiency.

The H. pylori β3GlcNAcT activity was also tested on I-antigen glycolipid glycans, Galβ4GlcNACβ6(GlcNAcβ3)Galβ4GlcNAcβ-sp. The enzyme retained 104% efficiency for GlcNAcβ3 incorporation onto the Galβ4GlcNAcβ6 antenna of the I-branched antigen glycan structure (A20).

Finally, the effects of terminal substitutions were evaluated on H. pylori β3GlcNAcT activity. Introducing a fucose to the two positions of galactose (A21) or three positions of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc; A22) of LacNAc-sp reduced, but did not block the β3GlcNAcT activity, resulting in a relative rate of 32% (A21) and 26% (A22), respectively. In contrast, the enzyme showed no activity on a terminal Gal with Neu5Acα2-6 substitution (A23). Terminal galactose with α-linkage, Galα1-3Gal- or Galα1-4Gal-, was not an acceptor substrate for the enzyme (A24 and A25).

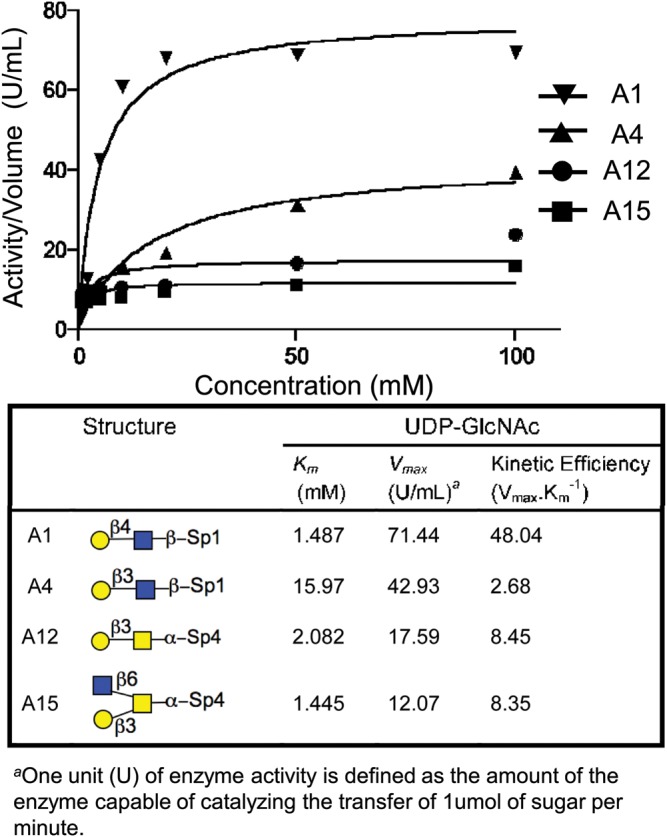

Kinetic parameters with type 1, type 2 and type 3 acceptor glycans

In addition to evaluating acceptor specificity at a fixed concentration of 10 mM, we examined the kinetic properties of key acceptor substrates to assess the potential to use the enzyme for preparative synthesis. To this end, the kinetic parameters (apparent Km and Vmax) were determined for four representative substrate precursors with UDP-GlcNAc as a donor (Figure 2). As expected, the highest kinetic efficiency of the enzyme was found for the type 2 LacNAc (A1) acceptor. The exemplary type 1 acceptor (A4) showed a Vmax ∼60% and ∼10-fold higher Km compared with the type 2 acceptor. The type 3 O-linked core 1 (A12) and core 2 (A15) acceptors showed a relative low activity with a Vmax ∼20% of the LacNAc reference substrate and a comparable Km with type 2 LacNAc.

Fig. 2.

Kinetic curve and characteristics of the H. Pylori β3GlcNAcT for four exemplary acceptor substrates. Reaction conditions are described in the Materials and Methods.

Although each acceptor differed in their kinetic properties, which accounts for differences in their activity in Figure 1, the studies strongly supported the potential for the use of the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT for the synthesis of extended glycans using all these acceptor substrates. Accordingly, we set out to systematically evaluate its use for the synthesis of both type 1 and type 2 poly-LacNAc repeats on diverse N-linked, O-linked and branched I-antigen glycan cores.

Synthesis of type 1 and type 2 extensions on branched LacNAc I-antigen

Linear and branched poly-LacNAc repeats characterize the histo-blood group i and I-antigens, respectively (Dejter-Juszynski et al. 1978; Jarnefelt et al. 1978; Fukuda et al. 1979, 1984), found on glycoproteins and glycolipids of most human cells and on glycoproteins of body fluids (Fukuda 1980; Fukuda et al. 1980; Turco et al. 1980; Fenderson et al. 1990; Muramatsu and Muramatsu 2004, 2008). Enzymes involved in poly-LacNAc biosynthesis of I-antigens have been identified (Ujita, McAuliffe, Suzuki, et al. 1999, 2000; Renkonen 2000; Korekane et al. 2003). While chemical synthesis of type 2 LacNAc extensions on a branched I-antigens has been reported (Severov et al. 2007), an efficient preparative enzymatic synthesis has not yet been documented.

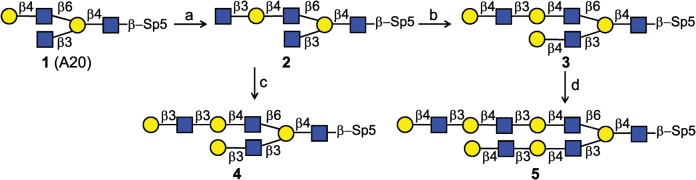

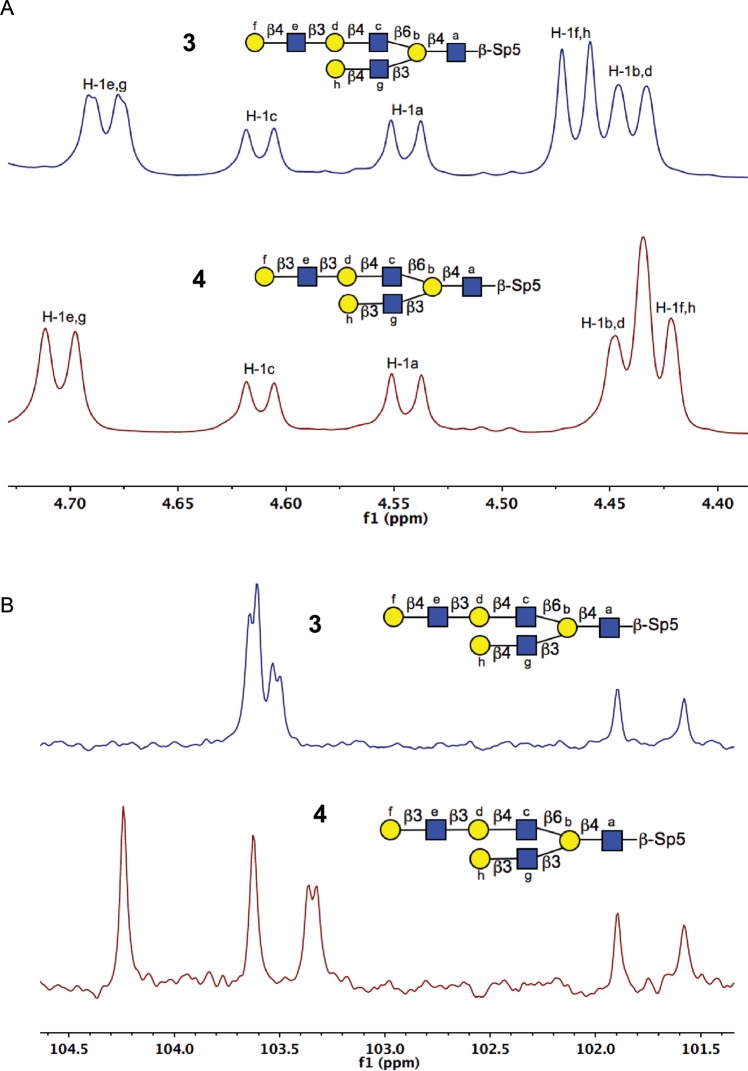

Scheme 1 displays the strategy of I-antigen poly-LacNAc synthesis starting with compound 1, which was chemically synthesized by the Dr N. Bovin group. An overnight incubation at 5 mg scale of 1 and excess UDP-GlcNAc with 25 mU H. pylori β3GlcNAcT led to the production of 2 in 95% yield. The matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) result (m/z 1221) confirmed one GlcNAc residue (m/z 203) was added to compound 1. A coupling constant of 8.4 Hz (δ 4.54 ppm, doublet) for the newly formed anomeric proton showed that this residue was in β-anomeric configuration as expected (Supplementary data). Compound 2 was incubated with bovine Gal-T1 or human Gal-T5 and UDP-Gal to produce type 2 or type 1 LacNAc extension on both antennae of I-antigen, giving compounds 3 (70% yield) and 4 (53% yield), respectively. Figure 3 displays the anomeric region comparison of 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of 3 and 4 for further characterization of these molecules as an exemplary characterization for type 1 (Galβ1-3GlcNAc) and type 2 (Galβ1-4GlcNAc) extensions. The data confirmed the specificity of the utilized enzymes, Gal-T1 and Gal-T5 in Galβ4 and Galβ3 incorporation, respectively, onto the GlcNAcβ3-R acceptor site. Compound 3 was extended with an additional LacNAc unit on each antenna by two-step incubations with H. pylori β3GlcNAcT and Gal-T1 in the presence of UDP-GlcNAc or UDP-Gal, respectively, to obtain compound 5 with tri-LacNAc extension on β6GlcNAc and di-LacNAc on β3GlcNAc antenna of I-antigen in 70% yield for two steps.

Scheme 1.

Strategy of type 1 and type 2 LacNAc extensions on I-antigen branched core structure. (a) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc (2.0 equiv.), 95%; (b) Gal-T1, UDP-Gal (4.0 equiv.), 80%; (c) Gal-T5, UDP-Gal (4.0 equiv.), 80%; (d) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc (4.0 equiv.), 80%; Gal-T1, UDP-Gal (4.0 equiv.), 88%. Optimal reactions conditions were used, as described in Results.

Fig. 3.

NMR comparison of compounds 3 and 4. (A) Anomeric region of 1H NMR of compounds 3 and 4 (assumed H-1c have the same chemical shift for comparison). (B) Anomeric region of 13C NMR of compounds 3 and 4. Exemplary of type 1 (Galβ1-3-R) and type 2 (Galβ1-4-R) poly-LacNAc extensions using human GalT5 and GalT-1, respectively. Reaction conditions are described in Materials and Methods.

Synthesis of type 1 and type 2 LacNAc extensions on biantennary N-glycopeptides

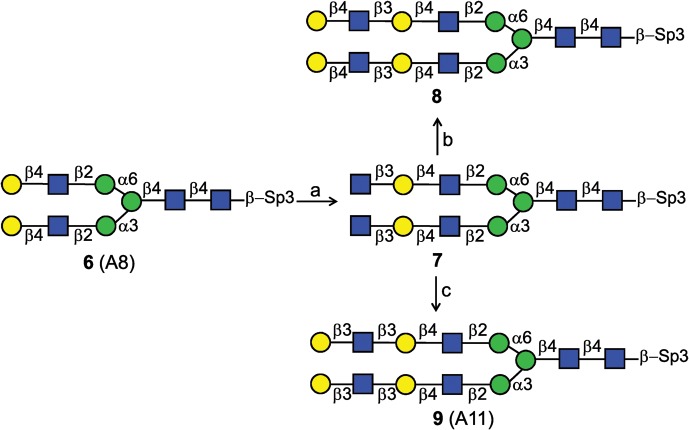

Scheme 2 illustrates the strategy of type 1 and type 2 LacNAc extensions on a natural asialo-N-glycopeptide substrate. Asialo glycopeptide 6 has a terminal type 2 LacNAc on each branch. Incubation of 6 with H. pylori β3GlcNAcT and UDP-GlcNAc in optimal conditions gave compound 7 (92% yield), biantennary N-glycopeptide with terminal LNT2 (GlcNAcβ3-LacNAc-) on each antenna, which allowed further type 2 and type 1 LacNAc extensions. Incubation of compound 7 and UDP-Gal with Gal-T1 or Gal-T5 lead to type 2 LacNAc (8, 95%) or type 1 LacNAc (9, 87%) on each antenna, respectively. It is noteworthy that, in our synthesis, the mammalian Gal-T1 displayed higher efficiency in galactosylation of branched glycans than the bacterial galactosyltransferase LgtB from Neisseria meningitidis.

Scheme 2.

Strategy of type 1 and type 2 LacNAc extensions on natural N-glycans. (a) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc (4.0 equiv.), 92%; (b) Gal-T1, UDP-Gal (4.0 equiv.), 92%; (c) Gal-T5, UDP-Gal (7.0 equiv.), 87%. Optimal reactions conditions were used, as described in Results.

Synthesis of type 1 and type 2 LacNAc repeats on core 1-α-Thr O-glycan

The LacNAc extended core 1 O-glycan derivatives are common glycoconjugates mainly detected on high endothelial venules and are known as L-selectin ligands (Yeh et al. 2001; Mitoma et al. 2003). In vitro synthesis of poly-LacNAc on serine- or threonine-conjugated core 1 has been reported with N. meningitidis β3GlcNAcT (LgtA; Naruchi et al. 2006). We assayed two bacterial β3GlcNAcTs from N. meningitidis (LgtA) and H. pylori to compare the efficiency of these enzymes on core 1-Thr. The results showed ∼10 times higher activity for H. pylori β3GlcNAcT than LgtA at transferring a GlcNAc residue to Core 1-α-Thr (Supplementary data).

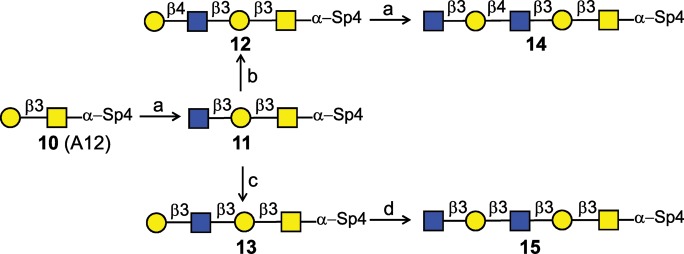

Scheme 3 illustrates the strategy of type 1 and type 2 LacNAc extensions with core 1-α-Thr. High concentration (50 mM) of core 1-α-Thr (10, 5 mg), to compensate for the high Km of the acceptor, and UDP-GlcNAc were incubated with increased amounts of H. pylori β3GlcNAcT (60 mU) to compensate for the low Vmax of the enzyme for the Galβ1-3GalNAc structure, resulting in the elongated compound 11 in 90% yield. Both the type 2 and type 1 mammalian galactosyltransferases, Gal-T1 and Gal-T5, showed good activity with compound 11 (Supplementary data), and overnight preparative reaction of 11 with UDP-Gal and Gal-T1 or Gal-T5 produced type 2 compound 12 (70% yield) or type 1 compound 13 (53% yield), respectively. Subsequent reaction with the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT yielded the extended core 1 pentasaccharides 14 (95%) and 15 (93%) in high yield.

Scheme 3.

Strategy of type 1 and type 2 LacNAc extensions on core 1 O-glycans. (a) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc (3.0 equiv.), 90% for 11, 95% for 14; (b) Gal-T1, UDP-Gal (2.3 equiv), 70%; (c) Gal-T5, UDP-Gal (3.0 equiv), 53%; (d) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc (3.0 equiv), 93%. Specific reactions conditions were used, as described in Results.

Selective synthesis of type 2 LacNAc extensions on one or both branches of O-linked core 2 glycans

Poly-LacNAc derivatives on core 2 O-glycans are the major components of mucin oligosaccharides and known to be involved in various biological functions and malignancies (Fukuda et al. 1986; Yousefi et al. 1991; Wilkins et al. 1996). The extended chains are usually found on the GlcNAcβ6 antenna, where the distal substitutions can generate functional glycan ligands for receptor binding (Ujita et al. 2000). Taking advantage of the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT flexibility and its different affinities toward various acceptor sites, in addition to the common core 2 poly-LacNAc extensions on antenna 6, we successfully synthesized unprecedented LacNAc extensions on both antennae of core 2.

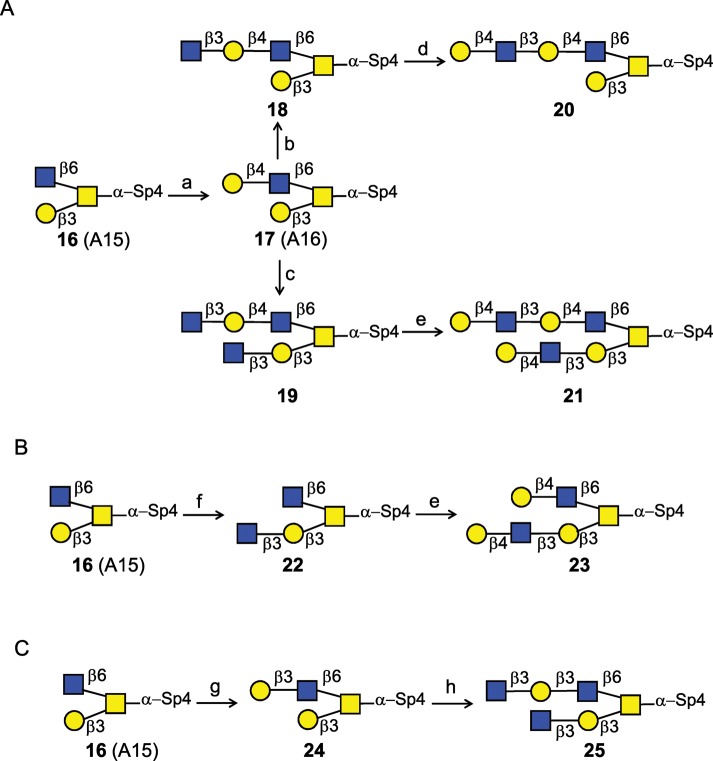

Scheme 4A illustrates the strategy of selective LacNAc extensions on β6 antenna of core 2 O-glycan. Addition of Gal to GlcNAc on antenna 6 was readily attainable by the incubation of 16 and UDP-Glc with LgtB/GalE fusion enzyme to achieve compound 17 in 100% yield, with two terminal Gal residues. Selective extension of the type 2 Galβ1-4GlcNAc acceptor sequence on antenna 6 was achieved by taking the advantage of the preferred acceptor specificity of the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT. Incubation of 10 mM 17 with UDP-GlcNAc and modest levels of enzyme (5.7 mU/μmol acceptor) leads to the production of compound 18, with a single GlcNAc added onto the favorable type 2 chain, while the unfavorable Galβ1-3 acceptor site remained unsubstituted. However, increasing the concentration of the acceptor 17 to 60 mM and supplementing the reaction with higher quantity of H. pylori β3GlcNAcT (8.2 mU/μmol acceptor) lead to GlcNAc incorporation onto both the Galβ1-4 and the Galβ1-3 of the substrate to produce the uncommon structure 19. The latter reaction did not go to completion and contained trace amounts compound 18 with one GlcNAc incorporated. However, successive galactosylation of the mixture of 19 and 18 with Gal-T1 leads to the production of two compounds: 21 in 80% yield with LacNAc extensions on both antennae and trace amounts of 20 which was easily separated by size exclusion chromatography on G25 superfine Sephadex.

Scheme 4.

Strategy of selective LacNAc extension on single and double chains of core 2 O-glycan. (a) LgtB/Gal-E, UDP-Glc (3.5 equiv.), 100%; (b) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc (2.0 equiv.), 95%; (c) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc (4.0 equiv.); (d) Gal-T1, UDP-Gal (1.5 equiv.), 98%; (e) Gal-T1, UDP-Gal (4.0 equiv.), 80% for 21 (two steps), 84% for 23 (two steps); (f) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc (4.0 equiv.); (g) Gal-T5, UDP-Gal (2.3 equiv.), 100%; (h) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc (4.0 equiv.), 30%. Specific reactions conditions were used, as described in Results.

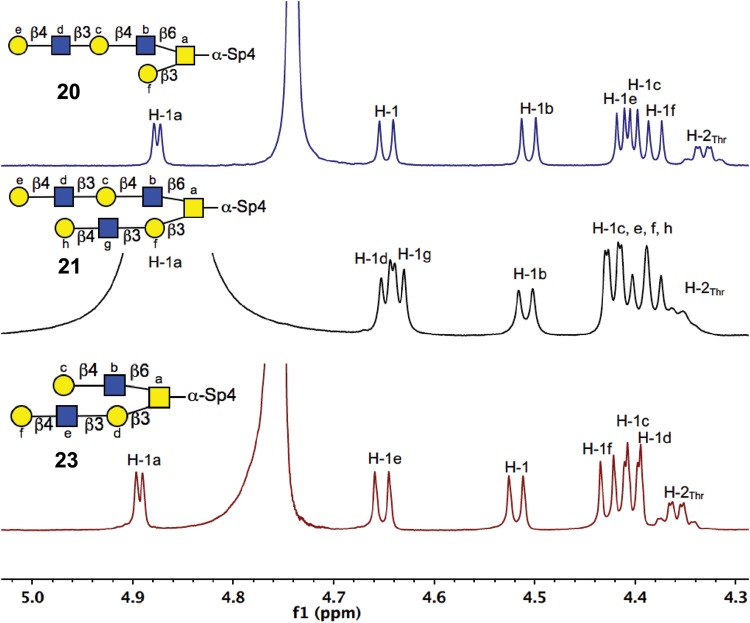

Scheme 4B illustrates the LacNAc extension procedure on intact core 2-α-Thr with only the Galβ1-3GalNAc sequence as an acceptor, which is a poor substrate for H. pylori β3GlcNAcT with a low Vmax. However, using an acceptor concentration of 50 mM 16 and increased amount of enzyme (17 mU/μmol acceptor) yielded the extended structure 22. Compound 22 was further galactosylated on both branches with Gal-T1 to produce compound 23, a core 2 derivative with LacNAc extensions on both antennae. Figure 4 shows the anomeric region comparison of 1H NMR spectra of compounds 20, 21 and 23. It shows that while both the antennae of compound 21 were extended with one LacNAc unit, only one LacNAc unit was introduced to one of antenna in compounds 20 and 23.

Fig. 4.

Anomeric region of 1H NMR of compounds 20, 21 and 23 (TMS at 0 ppm). Confirming poly-LacNAc extensions on alternative antennae of core 2 O-glycan, exploiting the kinetic specificities of H. Pylori β3GlcNAcT for type 2 and type 3 sequences.

Synthesis of type 1 LacNAc extensions on core 2

Type 1 LacNAc extension on core 2 O-glycan is shown in Scheme 4C. Compound 16 was incubated with Gal-T5 and UDP-Gal to form compound 24, with a Galβ1-3 extension on antenna 6 (Supplementary data). An overnight incubation with a high concentration compound 24 (50 mM) and UDP-GlcNAc and with excess amounts of enzyme (13.6 mU/μmol acceptor) successfully lead to the production of another uncommon structure 25, with GlcNAcβ1-3 extension of Galβ1-3, installing Galβ1-3/4 acceptor sites on both antennae of core 2-Thr (30% yield) for further elongations, which was confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

LacNAc extensions on cores 3, 4 and 6 O-glycans

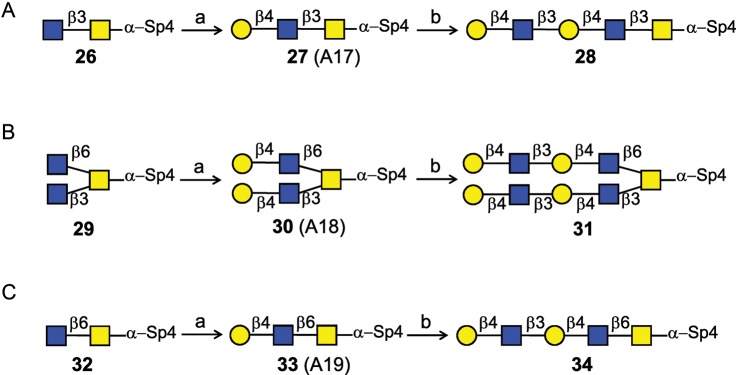

We explored the same strategy in the syntheses of other core structures (Scheme 5). The intact O-glycan core 3 (26), core 4 (29) and core 6 (32) were galactosylated with LgtB/Gal-E fusion enzyme and UDP-Glc, to provide the acceptor for β3GlcNAcT. The galactosylated compounds 27, 30 and 33 were incubated with H. pylori β3GlcNAcT and UDP-GlcNAc, in optimal conditions, to form intermediate structures for subsequent elongations. These intermediates were further galactosylated with Gal-T1 and UDP-Gal to produce di-LacNAc structures 28 (76%), 31 (77%) and 34 (80%).

Scheme 5.

Strategy of type 2 LacNAc extensions on core 3 (A), 4 (B) and 6 (C) O-glycans. (a) LgtB/Gal-E, UDP-Glc, 100% for 27, 100% for 30, 93% for 33; (b) H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, UDP-GlcNAc; Gal-T1, UDP-Gal, 76% for 28, 77% for 31, 80% for 34. Optimal reactions conditions were used, as described in Results.

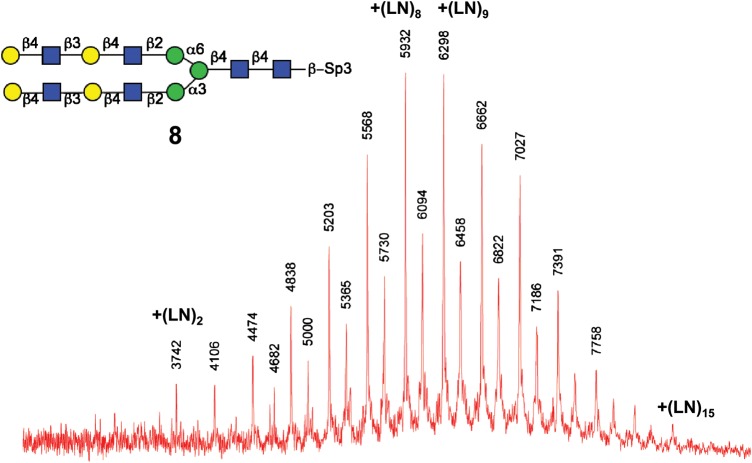

One-pot poly-LacNAc extension of a biantennary-N-glycopeptide with H. pylori β3GlcNAcT and Gal-T1

The capacity of H. pylori β3GlcNAcT for generating extended LacNAc repeats was tested in one-pot incubation of di-LacNAc biantennary-N-glycopeptide with H. pylori β3GlcNAcT and Gal-T1. The progression of the reaction was evaluated by MALDI-TOF MS (Figure 5) after 24 h incubation. The MS analysis of the products mixture suggested consecutive additions of up to 15 LacNAc units to the biantennary, illustrated as a series of sequential ion peaks representing alternative additions of GlcNAc and Gal residues. Products with eight and nine LacNAc repeats were prevalent in the mixture, which is consistent with the limited quantities of donor nucleotides (10 equiv.) in the reaction. Elongation may continue to produce longer chains with excess amounts of donor nucleotides. This experiment suggests that H. pylori β3GlcNAcT can be utilized in the synthesis of poly-LacNAcs with extended LacNAc repeats on natural branched glycans.

Fig. 5.

MS-TOF spectra of one-pot incubation of di-LacNAc biantennary N-glycopeptide with H. pylori β3GlcNAcT, Gal-T1 and UDP nucleotide donors (without fractionation). 8 (0.5 mg), H. pylori β3GlcNAcT (18 mU), Gal-T1 (18 mU), UDP-GlcNAc (10 equiv.), UDP-Gal (10 equiv.), 37°C, 24 h.

Discussion

The H. pylori β3GlcNAcT had been previously demonstrated to have utility in the synthesis of linear type 2 LacNAc repeats with LacNAc precursors (Sauerzapfe et al. 2009). Here, we show that this enzyme is of general utility for the synthesis of both type 1 and type 2 poly-LacNAc repeats on a diverse set of galactose-terminated substrates, including branched N-linked and O-linked glycan cores. Notable characteristics of the acceptor specificity of the enzyme include: (i) a requirement for a terminal galactose in β-configuration; (ii) a preference for acceptors with the type 2 Galβ1-4GlcNAc-β-R sequence; (iii) an ability to use Galβ1-3GlcNAc-R, as well as Galβ1-3GalNAc-R acceptors; (iv) an ability to extend both linear and branched LacNAc chains including N-linked, O-linked and I-antigen glycans; (v) no noticeable reduction in efficiency with acceptors of increasing number of LacNAc units. Such distinct characteristics make H. pylori β3GlcNAcT a superior β3GlcNAcT alternative in poly-LacNAc synthesis with a wide range of natural and modified glycans. The enzyme exhibited significantly decreased activity with fucosylated substrates. Considering that H. pylori β3GlcNAcT is naturally involved in the biosynthesis of the Lewis antigen in H. Pylori LPS, fucosylation may therefore have a regulatory effect on enzyme activity, i.e. fucosylation may naturally limit the LacNAc elongation in the bacteria.

Because of its broad acceptor specificity, the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT may be instrumental for preparative synthesis of poly-LacNAc backbones on various core structures. The kinetic specificity studies of four selected exemplary acceptors allowed preparative synthesis of 34 compounds, in milligram scale, with sequential poly-LacNAc extensions on natural glycans, several of which are unprecedented compounds with poly-LacNAc extensions on alternative antenna of branched glycans. These compounds may further be elaborated by various substitutions to generate specific glycan array platforms for glycan-binding investigations. Indeed, systematic synthesis of oligosaccharides with poly-LacNAcs is required to obtain a better insight in glycan–protein interactions and cell signaling.

Materials and methods

General

In addition to the methods described in General procedures for elongation of LN with different enzymes, the production of the H. pylori β3GlcNAcT (Sauerzapfe et al. 2009) and other methods are found in Supplementary data. Units of enzyme (U) are defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes incorporation of 1 µmol of GlcNAc, from the UDP-GlcNAc, onto an acceptor sequence per minute. In order to prevent the free nucleotide's inhibitory effects on the enzyme activity, alkaline phosphatase (CIP) was added into all the reactions to hydrolyze the free UDP to uridine and inorganic phosphate. It should be noted that the separation of the small molecular weight products (MW < 1200) from the reactants, namely sugar nucleotides, would only be possible by several gel filtration chromatography on G-25 followed by purification against an ion-exchange Dowex column. An exemplary chromatogram representing the purification of the product (MW = 2782) on a Sephadex™ G-25 Superfine gel filtration column is presented in Supplementary data.

H. pylori β3GlcNAcT enzyme activity assays

Assays were conducted in a 25-μL reaction mixture containing acceptor substrate (10 mM), enzyme (2.5 μL), KCl (25 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), dithiothreitol (DTT) (5 mM) and UDP-GlcNAc (12.5 nmol), UDP-[H3]-GlcNAc 2000 cpm/nmol) in Cacodylate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5) incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Reactions were terminated by the addition of cold dH2O (700 μL). The reaction mixtures were then passed through Pasteur pipette columns of Dowex-Cl resin (200–400 mesh, 1 μL). The columns were washed with 2 mL of dH2O and effluents were directly collected in scintillation vials and mixed with 4 mL of LSC-cocktail (Ultima Gold™ XR, PerkinElmer Life Science Inc., Waltham, MA), measured on liquid scintillation analyzer (Tri-Carb 2100TR, Packard BioScience, Waltham, MA). Under the above incubation conditions, the optimal enzyme activity for the favorable acceptor substrate, LacNAc-sp1 (A1), was calculated 1 U/mL. For substrate specificity evaluation, a concentration of 10 mM of each acceptor was used. For Km determination, substrate concentrations of 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 mM were used.

General procedure for elongation of LN with H. pylori β3GlcNAcT

The appropriate galactose terminated substrate (0.4–10.0 mg, 5–10 mM) was treated with UDP-GlcNAc (2.0 equiv./terminal galactose) in buffer A (50 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer, pH 7.2, with 25 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM MgCl2, 100 mU/mL of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase) and H. pylori β3GlcNAcT (3 mU/μmol acceptor) in an appropriate microcentrifuge tube. The reaction mixture was incubated in an isotherm incubator with agitating in 600 rpm at 37°C. If necessary, the pH of the solution was re-adjusted to 7.2 with 2 N NaOH, after 3 h. The reaction was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) with ethanol:NH4OH:H2O = 5:2:1 (by volume). The insoluble precipitates were removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was concentrated, passed through by Sephadex™ G-25 Superfine gel filtration column with 0.1 M NH4HCO3 (aq) eluent, and lyophilized to give the final product.

General procedure for enzymatic synthesis of LN with β4GalT from bovine milk (Gal-T1)

The appropriate GlcNAc terminated substrate (0.4–10.0 mg, 5–10 mM) was treated with UDP-Gal (2.0 equiv./terminal GlcNAc) in buffer B (50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.5, with 0.1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 20 mM MnCl2, 100 mU/mL of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase) and Gal-T1 (3 mU/μmol acceptor) in a microcentrifuge tube. The reaction mixture was incubated in an isotherm incubator with agitating in 600 rpm at 37°C. If necessary, the solution pH was adjusted to 7.5 with 2 N NaOH again after 3 h. The reaction was monitored by TLC with ethanol:NH4OH:H2O = 5:2:1 (by volume). The insoluble precipitates were removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was concentrated, passed through by Sephadex™ G-25 Superfine gel filtration column with 0.1 M NH4HCO3 (aq) eluent and lyophilized to give the final product.

General procedure for enzymatic synthesis of LN with β4GalT/GalE (LgtB fusion)

The appropriate GlcNAc terminated substrate (1.5–5.0 mg, 5–10 mM) and UDP-glucose (4.0 equiv./terminal GlcNAc) were combined in buffer C (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MnCl2, 100 mU/mL calf intestine alkaline phosphatase) with LgtB (3 mU/μmol acceptor) in an appropriate microcentrifuge tube. The reaction was incubated in an isotherm incubator with agitation at 600 rpm at 37°C. The reaction was monitored by TLC with ethanol:NH4OH:H2O = 5:2:1 (by volume). The insoluble precipitates were removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was purified on Sephadex™ G-25 Superfine gel filtration column with 0.1 M NH4HCO3 (aq) eluent. Pure product fractions were collected and lyophilized to give the final product.

General procedure for enzymatic synthesis of type 1 LacNAc with β3GalT (Gal-T5)

The appropriate GlcNAc terminated substrate (0.35–5.0 mg, 10–25 mM) was treated with UDP-Gal (2.5 equiv./terminal GlcNAc) in buffer C (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MnCl2, calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (100 mU/mL) and Gal-T5 (3 mU/μmol acceptor) in an appropriate microcentrifuge tube. The reaction was incubated in an isotherm incubator with agitation at 600 rpm at 37°C. The reaction was monitored by TLC with ethanol:NH4OH:H2O = 5:2:1 (by volume). The insoluble precipitates were removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was purified on Sephadex™ G-25 Superfine gel filtration column with 0.1 M NH4HCO3 (aq) eluent.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data for this article is available online at http://glycob.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM62116 and AI058113-07).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Abbreviations

β3GlcNAcT, β3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase; DTT, dithiothreitol; Gal, galactose; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; LN, N-acetyllactosamine; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MALDI-TOF MS, Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry; TLC, thin layer chromatography; UDP-Gal, uridine diphosphate galactose; UDP-Glc, uridine diphosphate glucose; UDP, uridine diphosphate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Ms. Anna Tran-Crie for administrative assistance.

References

- Bateman AC, Karamanska R, Busch MG, Dell A, Olsen CW, Haslam SM. Glycan analysis and influenza A virus infection of primary swine respiratory epithelial cells: The importance of NeuAcα2–6 glycans. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34016–34026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115998. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.115998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran A, Srinivasan A, Raman R, Viswanathan K, Raguram S, Tumpey TM, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. Glycan topology determines human adaptation of avian H5N1 virus hemagglutinin. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:107–113. doi: 10.1038/nbt1375. doi:10.1038/nbt1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings RD, Kornfeld S. The distribution of repeating [Gal beta 1,4GlcNAc beta 1,3] sequences in asparagine-linked oligosaccharides of the mouse lymphoma cell lines BW5147 and PHAR 2.1. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:6253–6260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejter-Juszynski M, Harpaz N, Flowers HM, Sharon N. Blood-group ABH-specific macroglycolipids of human erythrocytes: Isolation in high yield from a crude membrane glycoprotein fraction. Eur J Biochem. 1978;83:363–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12102.x. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis JW, Lau KS, Demetriou M, Nabi IR. Adaptive regulation at the cell surface by N-glycosylation. Traffic. 2009;10:1569–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00981.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan YY, Yu SY, Ito H, Kameyama A, Sato T, Lin CH, Yu LC, Narimatsu H, Khoo KH. Identification of further elongation and branching of dimeric type 1 chain on lactosylceramides from colonic adenocarcinoma by tandem mass spectrometry sequencing analyses. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16455–16468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707274200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M707274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenderson BA, Eddy EM, Hakomori S. Glycoconjugate expression during embryogenesis and its biological significance. Bioessays. 1990;12:173–179. doi: 10.1002/bies.950120406. doi:10.1002/bies.950120406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M. K562 human leukaemic cells express fetal type (i) antigen on different glycoproteins from circulating erythrocytes. Nature. 1980;285:405–407. doi: 10.1038/285405a0. doi:10.1038/285405a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Carlsson SR, Klock JC, Dell A. Structures of O-linked oligosaccharides isolated from normal granulocytes, chronic myelogenous leukemia cells, and acute myelogenous leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:12796–12806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Dell A, Oates JE, Fukuda MN. Structure of branched lactosaminoglycan, the carbohydrate moiety of band 3 isolated from adult human erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:8260–8273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Fukuda MN, Hakomori S. Developmental change and genetic defect in the carbohydrate structure of band 3 glycoprotein of human erythrocyte membrane. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:3700–3703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Fukuda MN, Papayannopoulou T, Hakomori S. Membrane differentiation in human erythroid cells: Unique profiles of cell surface glycoproteins expressed in erythroblasts in vitro from three ontogenic stages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3474–3478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3474. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.6.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda MN, Hakomori S. Structures of branched blood group A-active glycosphingolipids in human erythrocytes and polymorphism of A- and H-glycolipids in A1 and A2 subgroups. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:446–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiling H. Structure and biological functions of keratan sulfate proteoglycans. Exs. 1994;70:101–122. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7545-5_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EH. Characterization and membrane organization of beta 1,3- and beta 1,4-galactosyltransferases from human colonic adenocarcinoma cell lines Colo 205 and SW403: Basis for preferential synthesis of type 1 chain lacto-series carbohydrate structures. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;270:630–646. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90546-8. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(89)90546-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horlacher T, Oberli MA, Werz DB, Krock L, Bufali S, Mishra R, Sobek J, Simons K, Hirashima M, Niki T, et al. Determination of carbohydrate-binding preferences of human galectins with carbohydrate microarrays. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1563–1573. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000020. doi:10.1002/cbic.201000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarnefelt J, Rush J, Li YT, Laine RA. Erythroglycan, a high molecular weight glycopeptide with the repeating structure [galactosyl-(1 leads to 4)-2-deoxy-2-acetamido-glucosyl(1 leads to 3)] comprising more than one-third of the protein-bound carbohydrate of human erythrocyte stroma. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:8006–8009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korekane H, Taguchi T, Sakamoto Y, Honke K, Dohmae N, Salminen H, Toivonen S, Helin J, Takio K, Renkonen O, et al. Purification and cDNA cloning of UDP-GlcNAc:GlcNAcbeta1-3Galbeta1-4Glc(NAc)-R [GlcNAc to Gal]beta1,6N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase from rat small intestine: A major carrier of dIGnT activity in rat small intestine. Glycobiology. 2003;13:387–400. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg044. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwg044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen A, Niemela R, Renkonen O. Enzymatic midchain branching of polylactosamine backbones is restricted in a site-specific manner in α1,3-fucosylated chains. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13729–13735. doi: 10.1021/bi9712807. doi:10.1021/bi9712807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen A, Penttila L, Renkonen O, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Glycosulfopeptides with O-glycans containing sialylated and polyfucosylated polylactosamine bind with low affinity to P-selectin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39749–39759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206281200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen A, Salminen H, Zhu Y, Maaheimo H, Helin J, Costello CE, Renkonen O. In vitro biosynthesis of a decasaccharide prototype of multiply branched polylactosaminoglycan backbones. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7026–7036. doi: 10.1021/bi9627673. doi:10.1021/bi9627673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Fan YY, Chen YY, Wang SH, Chen CI, Yu LC, Khoo KH. Enhanced expression of beta 3-galactosyltransferase 5 activity is sufficient to induce in vivo synthesis of extended type 1 chains on lactosylceramides of selected human colonic carcinoma cell lines. Glycobiology. 2009;19:418–427. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn156. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwn156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan SM, Altman E, Mykytczuk O, Brisson JR, Chandan V, Schur MJ, St Michael F, Masson A, Leclerc S, Hiratsuka K. Novel biosynthetic functions of lipopolysaccharide rfaJ homologs from Helicobacter pylori. Glycobiology. 2005;15:721–733. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi057. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwi057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maaheimo H, Penttila L, Renkonen O. Enzyme-aided construction of medium-sized alditols of complete O-linked saccharides. The constructed hexasaccharide alditol Gal beta 1-4GlcNAc beta 1-6Gal beta 1-4GlcNAc beta 1-6(Gal beta 1-3)GalNAc-ol resists the action of endo-beta-galactosidase from Bacteroides fragilis. FEBS Lett. 1994;349:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00638-5. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)00638-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maaheimo H, Renkonen R, Turunen JP, Penttila L, Renkonen O. Synthesis of a divalent sialyl Lewis x O-glycan, a potent inhibitor of lymphocyte-endothelium adhesion. Evidence that multivalency enhances the saccharide binding to L-selectin. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:616–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.616_b.x. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.616_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe JC, Fukuda M, Hindsgaul O. Expedient synthesis of a series of N-acetyllactosamines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:2855–2858. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00485-0. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(99)00485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoma J, Petryniak B, Hiraoka N, Yeh JC, Lowe JB, Fukuda M. Extended core 1 and core 2 branched O-glycans differentially modulate sialyl Lewis X-type L-selectin ligand activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9953–9961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212756200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M212756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu H, Kusano T, Sato M, Oda Y, Kobori K, Muramatsu T. Embryonic stem cells deficient in I β1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase exhibit reduced expression of embryoglycan and the loss of a Lewis X antigen, 4C9. Glycobiology. 2008;18:242–249. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm138. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwm138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu T, Muramatsu H. Carbohydrate antigens expressed on stem cells and early embryonic cells. Glycoconj J. 2004;21:41–45. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000043746.77504.28. doi:10.1023/B:GLYC.0000043746.77504.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagae M, Nishi N, Murata T, Usui T, Nakamura T, Wakatsuki S, Kato R. Structural analysis of the recognition mechanism of poly-N-acetyllactosamine by the human galectin-9 N-terminal carbohydrate recognition domain. Glycobiology. 2009;19:112–117. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn121. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwn121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruchi K, Hamamoto T, Kurogochi M, Hinou H, Shimizu H, Matsushita T, Fujitani N, Kondo H, Nishimura S. Construction and structural characterization of versatile lactosaminoglycan-related compound library for the synthesis of complex glycopeptides and glycosphingolipids. J Org Chem. 2006;71:9609–9621. doi: 10.1021/jo0617161. doi:10.1021/jo0617161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieduszynski IA, Huckerby TN, Dickenson JM, Brown GM, Tai GH, Bayliss MT. Structural aspects of skeletal keratan sulphates. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990;18:792–793. doi: 10.1042/bst0180792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemela R, Natunen J, Majuri ML, Maaheimo H, Helin J, Lowe JB, Renkonen O, Renkonen R. Complementary acceptor and site specificities of Fuc-TIV and Fuc-TVII allow effective biosynthesis of sialyl-TriLex and related polylactosamines present on glycoprotein counterreceptors of selectins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4021–4026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4021. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.7.4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nycholat CM, McBride R, Ekiert DC, Xu R, Rangarajan J, Peng W, Razi N, Gilbert M, Wakarchuk W, Wilson IA, et al. Recognition of sialylated poly-N-acetyllactosamine chains on N- and O-linked glycans by human and avian influenza A virus hemagglutinins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:4860–4863. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkonen O. Enzymatic in vitro synthesis of I-branches of mammalian polylactosamines: Generation of scaffolds for multiple selectin-binding saccharide determinants. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:1423–1439. doi: 10.1007/PL00000627. doi:10.1007/PL00000627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkonen O, Toppila S, Penttila L, Salminen H, Helin J, Maaheimo H, Costello CE, Turunen JP, Renkonen R. Synthesis of a new nanomolar saccharide inhibitor of lymphocyte adhesion: Different polylactosamine backbones present multiple sialyl Lewis x determinants to L-selectin in high-affinity mode. Glycobiology. 1997;7:453–461. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.4.453-c. doi:10.1093/glycob/7.4.453-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauerzapfe B, Krenek K, Schmiedel J, Wakarchuk WW, Pelantova H, Kren V, Elling L. Chemo-enzymatic synthesis of poly-N-acetyllactosamine (poly-LacNAc) structures and their characterization for CGL2-galectin-mediated binding of ECM glycoproteins to biomaterial surfaces. Glycoconj J. 2009;26:141–159. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9172-2. doi:10.1007/s10719-008-9172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppo A, Penttila L, Niemela R, Maaheimo H, Renkonen O, Keane A. Enzymatic synthesis of octadecameric saccharides of multiply branched blood group I-type, carrying four distal α1,3-galactose or β1,3-GlcNAc residues. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4655–4661. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a019. doi:10.1021/bi00014a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severov VV, Belyanchikov IM, Pazynina GV, Bovin NV. Synthesis of N-acetyllactosamine-containing oligosaccharides, galectin ligands. Russ J Bioorg Chem+ 2007;33:122–138. doi: 10.1134/s1068162007010141. doi:10.1134/S1068162007010141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan N, Bane SM, Ahire SD, Ingle AD, Kalraiya RD. Poly N-acetyllactosamine substitutions on N- and not O-oligosaccharides or Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen facilitate lung specific metastasis of melanoma cells via galectin-3. Glycoconj J. 2009;26:445–456. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9194-9. doi:10.1007/s10719-008-9194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell SR, Arthur CM, Slanina KA, Horton JR, Smith DF, Cummings RD. Dimeric Galectin-8 induces phosphatidylserine exposure in leukocytes through polylactosamine recognition by the C-terminal domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20547–20559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802495200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M802495200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togayachi A, Kozono Y, Ishida H, Abe S, Suzuki N, Tsunoda Y, Hagiwara K, Kuno A, Ohkura T, Sato N, et al. Polylactosamine on glycoproteins influences basal levels of lymphocyte and macrophage activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15829–15834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707426104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707426104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togayachi A, Kozono Y, Kuno A, Ohkura T, Sato T, Hirabayashi J, Ikehara Y, Narimatsu H. Beta3GnT2 (B3GNT2), a major polylactosamine synthase: Analysis of B3GNT2-deficient mice. Methods Enzymol. 2010;479:185–204. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)79011-X. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(10)79011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turco SJ, Rush JS, Laine RA. Presence of erythroglycan on human K-562 chronic myelogenous leukemia-derived cells. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:3266–3269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujita M, McAuliffe J, Hindsgaul O, Sasaki K, Fukuda MN, Fukuda M. Poly-N-acetyllactosamine synthesis in branched N-glycans is controlled by complemental branch specificity of i-extension enzyme and beta 1,4-galactosyltransferase I. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16717–16726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16717. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.24.16717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujita M, McAuliffe J, Suzuki M, Hindsgaul O, Clausen H, Fukuda MN, Fukuda M. Regulation of I-branched poly-N-acetyllactosamine synthesis. Concerted actions by I-extension enzyme, I-branching enzyme, and beta1,4-galactosyltransferase I. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9296–9304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9296. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.14.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujita M, M J, Hindsgaul O, Sasaki K, Fukuda MN, Fukuda M. Poly-N-acetyllactosamine synthesis in branched N-glycans is controlled by complemental branch specificity of i-extension enzyme and β1,4-galactosyltransferase I. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16717–16726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16717. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.24.16717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujita M, Misra AK, McAuliffe J, Hindsgaul O, Fukuda M. Poly-N-acetyllactosamine extension in N-glycans and core 2- and core 4-branched O-glycans is differentially controlled by i-extension enzyme and different members of the beta 1,4-galactosyltransferase gene family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15868–15875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001034200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M001034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasiliu D, Razi N, Zhang Y, Jacobsen N, Allin K, Liu X, Hoffmann J, Bohorov O, Blixt O. Large-scale chemoenzymatic synthesis of blood group and tumor-associated poly-N-acetyllactosamine antigens. Carbohydr Res. 2006;341:1447–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.03.043. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins PP, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Structures of the O-glycans on P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 from HL-60 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18732–18742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18732. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.31.18732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh JC, Hiraoka N, Petryniak B, Nakayama J, Ellies LG, Rabuka D, Hindsgaul O, Marth JD, Lowe JB, Fukuda M. Novel sulfated lymphocyte homing receptors and their control by a core1 extension beta 1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. Cell. 2001;105:957–969. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00394-4. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi S, Higgins E, Daoling Z, Pollex-Kruger A, Hindsgaul O, Dennis JW. Increased UDP-GlcNAc:Gal beta 1–3GaLNAc-R (GlcNAc to GaLNAc) beta-1, 6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase activity in metastatic murine tumor cell lines. Control of polylactosamine synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1772–1782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdebska E, Krauze R, Koscielak J. Structure and blood-group I activity of poly(glycosyl)-ceramides. Carbohydr Res. 1983;120:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(83)88011-2. doi:10.1016/0008-6215(83)88011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.