Abstract

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is an uncommon, distinctive cutaneous ulceration which is usually idiopathic, but may be associated with many systemic disorders. The etipathogenesis of of PG is still not well understood. Clinically it is classified into ulcerative, pustular, bullous and vegetative types. A few atypical and rare variants have also been described. The diagnosis mainly depends on the recognition of evolving clinical features as investigations only assist in the diagnosis. In view of this a few criteria have been proposed for the diagnosis of PG. the treatment mainly consists of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents. A few new agents have also been tried in the management.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, pyoderma gangrenosum, ulcerative

INTRODUCTION

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare inflammatory disease of unknown etiology characterized by neutrophilic infiltration of the dermis and destruction of the tissue.[1] PG was first described by Brocq in 1916 as “phagedenisme geometrique” and later named by Brunsting et al.[2] The latter author considered PG to be the dissemination of a distant focus of infection (i.e., the bowel in ulcerative colitis or lungs in empyema).[3] Presently PG is considered a reactive inflammatory dermatosis and part of the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatosis.[4]

EPIDEMIOLOGY

PG is a rare disease and the incidence of this disease is uncertain. It is estimated to be 3-10 patients per million population per year. In one of our case series, it constituted 0.03% of the new dermatology cases seen in the hospital.[2] Annual incidence in southern Germany has been reported to be 2 cases per year per 106 population. The peak incidence occurs between the ages of 20-50 years with a possible slight female preponderance, and approximately 4% of patients are children.[2,5] However, in our Indian case series we found a larger number of pediatric PG cases and a lower mean age, which may indicate involvement of an infective agent in the etiopathogenesis of PG.[2]

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The precise etiopathogenesis of PG is not well understood. However immunological factors and neutrophil dysfunction can be considered to be involved in etiopathogenesis of PG.[2]

Immunological factors

The following immunological factors can be considered:

Frequent association of PG with autoimmune diseases.

Pathergy phenomenon indicating an abnormal response to an inciting stimuli such as trauma.[1]

Defective cell-mediated immune response in PG.[6]

Deposition of immunoglobulins in the dermal blood vessels. Monoclonal or polyclonal hyperglobulinemia may also be associated with PG.[3]

However, the immunological abnormalities associated with PG are not always consistently observed in all patients and it is unclear whether or not they are an epiphenomena.[3]

Neutrophil dysfunction

PG is considered part of the spectrum of the neutrophilic disease. Impaired phagocytosis by neutrophils has been suggested in the pathogenesis of PG. Neutrophil analysis in PG showed evidence of abnormal neutrophil trafficking and aberrant integrin oscillations.[4] Interleukin-8 (IL-8), a potent leucocyte chemotactic agent, has been shown to be overexpressed in PG ulcers. In the recently described “PAPA syndrome” (pyogenic sterile arthritis, PG and acne) there is an overexpression of the IL-16 gene and the 1L-16 protein is chemotactic to neturophils. It can be concluded that the factors triggering/maintaining the various immunological/neutrophil abnormalities are multiple and include genetic predisposition, parainflammatory, paraneoplastic or para immune phenomena.[3] The predisposed patient experiences an inciting event such as minor trauma, and instead of normal response that recognizes and removes the damaged tissue, the patient"s abnormal response results in lesions of PG.[2]

PG can also arise as a consequence of drug therapy like propylthiouracil, pegfilgastrim (granulocyte stimulating factor), gefinib (epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor), and isotretinoin.[7,8]

Clinical features

The description of PG by Brunsting et al., in their original article, is still very relevant for the classic ulcerative form of the disease. They described PG as follows:

The borders of ulcers are well defined because of their striking blue color which clearly outlined the lesions as it extended peripherally in rough, serpiginous configuration. The blue zone consisted of an edematous boggy strip from 5-8 mms wide in which there had been exclusive undermining and necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue, the epidermis remaining as a thin, gray translucent film extending over the crater of the lesion in a ragged, irregular fashion. On the advance of the underlying process, often at the rate of 1-2 cms in 24 hrs, a zone of erythema extends as an areola into the area of normal skin. The lesion occurred as crops of small, discrete pustules surrounded by an inflammatory areola. Within a few days, the centre of the pustule softened and the covering became blue and broken down. The lesion either underwent involution or extended peripherally to coalesce with others.[9]

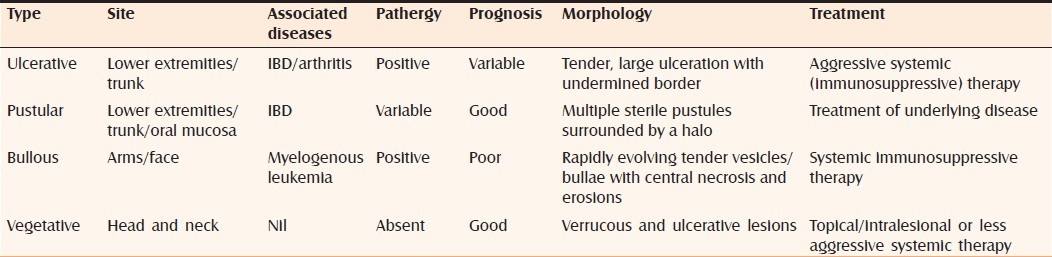

Ulcerative (classic form) PG [Figure 1] is the most common type of PG and the salient feature is a necrotic and mucopurulent tender ulcer with an edematous, violaceous, serpignously expanding, undermined border.[2,3] It usually appears on the lower limb and the trunk but may occur at any site.[7]

Figure 1.

Ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum

The clinical course may present two patterns:

Explosive onset and rapidly progressive

Indolent and gradually progressive.

The former pattern is characterized by sudden onset with rapid progression and severe necrosis, whereas the latter is characterized by gradual progression and spontaneous regression.[3]

Pustular PG [Figure 2] was first described by O Laughlin and Perry in association with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).[3] It is considered a forme fruste of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum in which pustules do not evolve into ulcers. In such patients, pustules are painful and occur mainly on the extensor aspects of the extremities and upper trunk.[5] Pustular PG is usually associated with exacerbations of IBD and manifests with fever and arthralgias. However, in one of the reports, two patients with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease developed pustular PG.[10] In our case series, two patients had a combination of pustular and ulcerative lesions in the absence of associated IBD.[2]

Figure 2.

Pustular pyoderma gangrenosum

Bullous or atypical PG [Figure 3] was first described by Perry and Winklemann in 1972, characterized by rapidly evolving vesicles/bullae with central necrosis and erosion with an areola of erythema. This type of PG is considered to be due to rapid superficial necrosis. It is usually seen on the face and arms rather than on the legs. It is reported in patients who have myloproliferative diseases like leukemia. Because of the clinical appearance, some authors believe that bullous PG and atypical Sweet's syndrome represent different points in the same spectrum of reactive skin conditions in patients with myeloproliferative diseases.[3,5,11]

Figure 3.

Bullous pyoderma gangrenosum

Vegetative PG [Figure 4] is a localized, nonaggressive form of PG first described by Wilson–Jones and Winklemann who termed this variety as superficial granulomatous pyoderma.[12] The entity was originally described as malignant pyoderma, but Gibson et al. analyzed some of these cases as an atypical form of Wegener's Granulomatosis.[3]

Figure 4.

Vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum

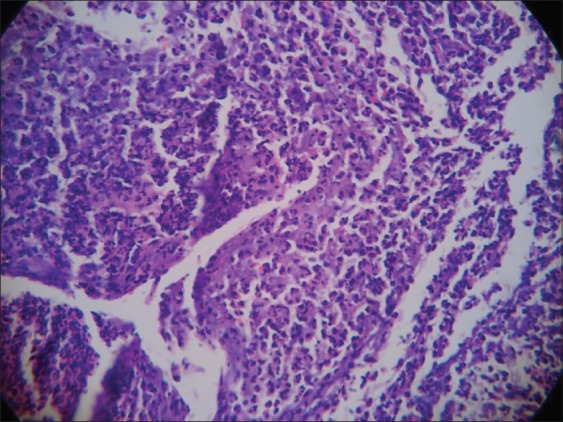

Figure 5.

Ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum histopathology (H and E, 10×10)

Rare variants

Peristomal PG is a rare subset seen around enterostomy/colonostomy in patients with IBD. It is considered a pathergy phenomenon due to irritation to the peristomal skin casued by leakage of faecus or by the adhesive stomal appliance.[3,13]

Genital involvement in PG may be seen in association with ulcers elsewhere in the body. Vulvar, penile, and scrotal involvement has also been described as a solitary manifestation of PG.[14–17] When genital lesions are present Behcet's disease has to be ruled out in addition to other causes of genital ulcers.[3] Gential and buttock PG present more in the infantile age group than in others. PG in association with HIV infection may show involvement of perineum complicated by secondary bacterial infection.[18]

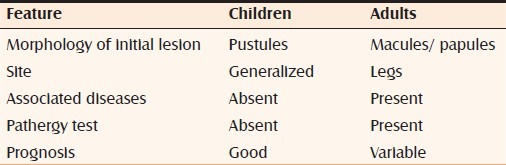

PG in infants and children is rare (4% only).[19] However in our case series we had a higher percentage of cases in children. In children, the lesions are generalized and with involvement of genital areas. However, clinical appearance, location, and response to treatment resemble those of the classic lesions in adults.[2] The possible differences between adults and children are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Differences between childhood and adult form of pyoderma gangrenosum

Extracutaneous neutrophilic disease refers to sterile neutrophilic infiltrates occurring in various internal organs. Pulmonary neutrophilic infiltrates are the most commonly reported extracutaneous sign.[3,20]

Pyostomatitis vegetans is considered as oral pustular PG characterized by a pustular, vegetative process of mucous membrane.[21] The oral lesions usually coincide with the active exacerbations in IBD [Table 2].[3]

Table 2.

Clinical features of pyoderma gangrenosum

The “pathergy,” first described by Blobner, refers to the localization of PG to sites of skin damaged by trauma, surgery or venepuncture.[22] It probably represents a localized, misdirected host-mediated effector cell response to cutaneous tissue antigenically changed by trauma in a patient with altered immune reactivity.[10] Pathergy is seen in nearly 25% of the patients with PG.[4] We have reported that pathergy is more common in PG associated with systemic disease.[2]

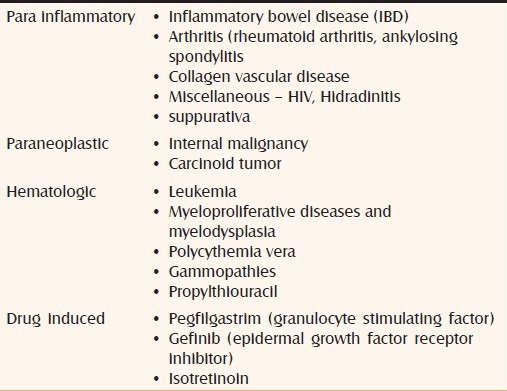

Associated diseases

Approximately 50% of patients with PG have an associated systemic disease. These diseases may precede, follow or occur simultaneously.[23] Depending upon the associated conditions PG was also be classified as follows:

Parainflammatory (paraimmune) (associated with IBD, collagen vascular diseases, arthritis, etc)

Paraneoplastic (associated with malignancy)

Hemotologic (leukemias, polycythemia)

Drug induced

Idiopathic

The most common associations are IBD, arthritis, and hematologic diseases. PG associated with IBD is characterized by ulcerative or pustular PG. Oral and peristomal PG can also occur. PG in association with myeloproliferative diseases may present with bullous PG.[3] In patients with HIV infection, perineum is the most common site of involvement and ulcers are often secondarily infected with bacterial organisms [Table 3].[19]

Table 3.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (associated diseases)

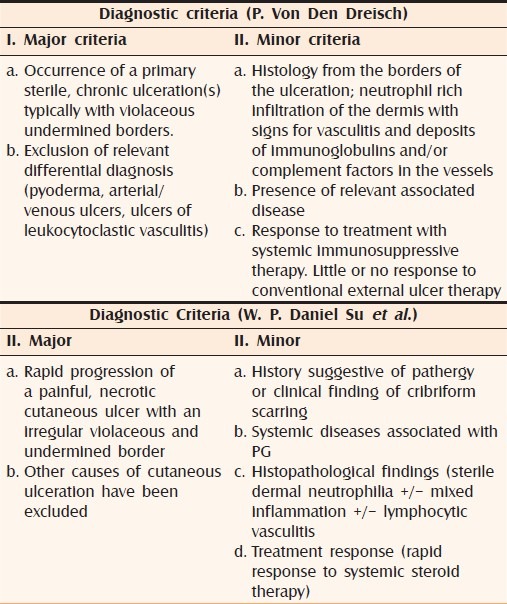

Criteria for the diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum

Table 4 enumerates the criteria proposed by various authors.[4,24]

Table 4.

Proposed diagnostic criteria

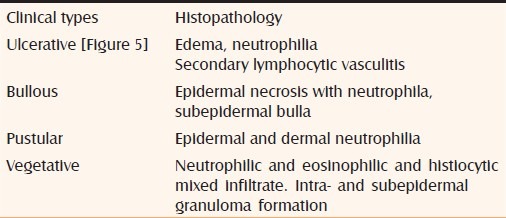

Diagnosis

The diagnosis mainly depends on recognition of the evolving clinical features and is only supported by histopathology.[5] The histopathologic changes depend on the type of the lesion being studied, the stage of the evolution of the lesion, and the site from which the biopsy specimen is obtained in a given lesion. The histopathologic distinction of PG from other ulcerative processes with dermal neutrophilia is challenging and at times impossible.[25] Massive neutrophilic infiltration (authors prefer to call it as “sea of neutrophils”), in the absence of vasculitis and granuloma formation, is typical of PG.[20] However it has been shown that PG lesions when associated with Crohn's disease may contain granulomatous foci.[26,27] The histopathology of various morphologic types of PG is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Histopathology of pyoderma gangrenosum

PG has to be differentiated from the following categories of diseases:

Vaso-occlusive and venous diseases.

Systemic vasculitis - Wegener's granulomatosis, livedoid vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa, etc.

Infections - subcutaneous mycoses, tuberculosis, syphilis, ecthyma gangrenosum.

Malignancies - lymphomas, leukemia.

External tissue injury - insect bites, factitious panniculitis.

Other neutrophilic dermatoses - atypical Sweet's syndrome, Behcet's disease.

Drug reaction - pustular drug reaction, halogenoderma.

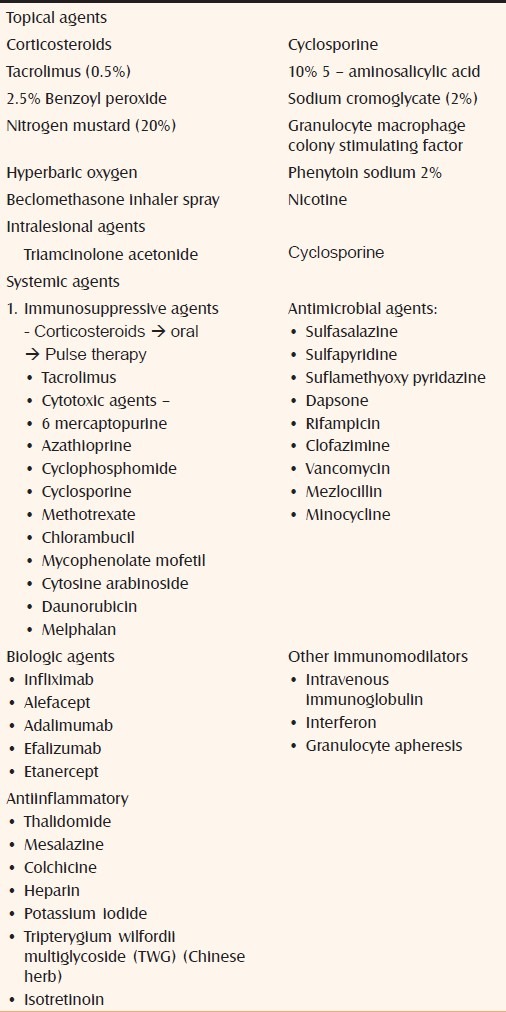

Treatment

It is essential to exclude other diagnosis such as infectious disease before therapy is initiated as corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy is the mainstay in the treatment of PG. The treatment of underlying disease may aid in healing. In patients without an identifiable associated disease, it is still possible for it to appear later; hence follow-up and evaluation are required even after the skin lesions have healed.[28] The disease behaves in an unpredictable manner and in both acute and chronic forms spontaneous healing can occur, but as old lesions resolve, new lesions may appear.[3]

Various topical and systemic agents used in the treatment of PG are enumerated in Table 6. The exhaustive list indicates that there is no single agent which is useful in all cases of PG. With the exception of the study by Brooklyn et al., there are no placebo-controlled trials in the treatment of PG. This may be because of rarity of PG and ethical consideration involved in giving a placebo to a patient with PG.[29]

Table 6.

Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum

Local therapy

Local therapy is an important adjunct to systemic therapy and may provide relief from symptoms. As most of the ulcers show heavy exudates, foam/laminate dressings are recommended. In the case of sloughy or purulent ulcers wet compresses with saline and alginate dressings are useful.[7] Aggressive surgical debridement or skin grafting is discouraged because of the risk of a pathergic response. Although some topical agents such as tacrolimus, potent corticosteroids, and cyclosporine have reported efficacy, evidence from large clinical trials is lacking.[29,30] Applications of beclomethasone inhaler 4 puffs to the peristomal PG have been reported to be successful.[31] Phenytoin sodium 2% solution has also been reported to be beneficial.[32] Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is thought to benefit PG elevating oxygen tension in the ulcers either through the greater arterial oxygen supplied to the capillary bed or through the local delivery of oxygen to the ulcer surface.[33] Skin grafting or microvasular flap grafting may be successful in nonprogressive disease or a systemic steroid cover is given. Cultured keratinocyte autografts and allografts have also been reported to be useful in some cases [Table 6].[30]

Systemic therapy

Systemic corticosteroids have been the most predictable and effective treatment of acute, rapidly progressive form of the disease. High doses of prednisolone or pulse therapy with suprapharmocologic doses of methylprednisolone/dexamethasone may have to be used in resistant disease.[3,30] Among the immunosuppressive agents cyclosporine which does not cause significant myelosuppression has proved to be a useful substitute therapy for PG resistant to steroid treatment.[28]

Sulfa drugs may be used either alone or as a steroid sparing agent to maintain improvement in PG.[3]

More recently, tumor necrosis factor – alpha (TNF-alpha) blockers and other injectable biologics have been demonstrated to be successful.[29] Infliximab (5 mg/kg/week intravenously at weeks 0, 2, 6 and at every 6-8 weeks), adalimumab (40 mg subcutaneously weekly), all seem to be effective in PG –especially in association with IBD.[34] Infliximab is the only biologic reported to be efficacious in a randomized double blind placebo control trial.[33] Adalimumab has also been reported to be successful in recalcitrant PG with comparable efficacy to infliximab.[35] Two of the patients who showed recurrence also responded to adalimumab. Biologics like efalizumab and alefacept have also been used successfully in the management of PG.[29] Even though isotretinoin is used successfully in the treatment of superficial PG, it has also been reported to cause PG.[8,36]

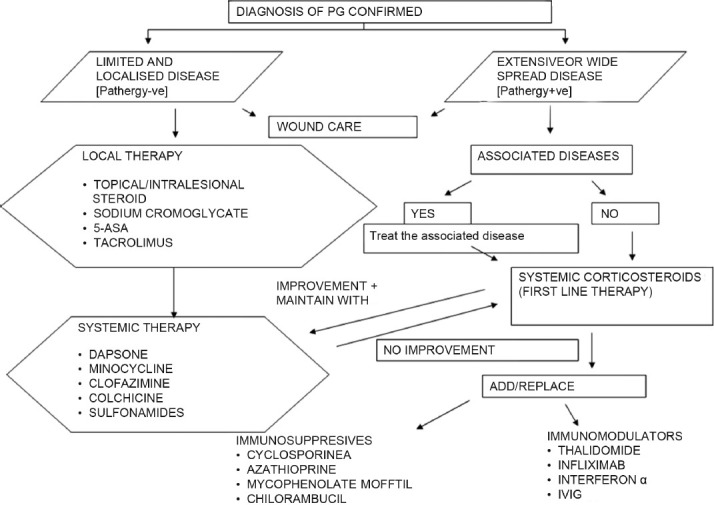

The various systemic agents used in the treatment of PG are listed in Table 6. We have presented an algorithm for the treatment of PG [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Suggested treatment algorithm for pyoderma gangrenosum

CONCLUSION

Thus, although PG is clinically characteristic, it remains an enigma with regard to its etiopathogenesis. There are various clinical and histological variants of the disease. Criteria have been proposed to diagnose PG. The various therapeutic agents including biologics have been used in the management of the disease.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Powell FC, Hackett BC. Pyoderma Gangrenosum. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SL, Gilchrist BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Vol. 1. New York: McGraw Hill; 2007. pp. 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhat RM, Nandakishore B, Sequeira FF, Sukumar D, Kamath GH, Martis J, et al. Pyoderma Gangrenosum: An Indian perspective. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:242–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruocco E, Sangiuliano S, Gravina AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G. Pyoderma gangrenosum: An updated review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1008–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:790–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: Classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:395–409. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell FC, Schroeter AL, Perry HO, Su WP. Direct immunofluorescence in pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 1983;108:287–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb03966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wollina U. Pyoderma grangrenosum: A review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tinoco MP, Tamler C, Maciel G, Soares D, Avelleria JC, Azulay D. Pyoderma Gangrenosum following isotretinoin therapy for acne nodulocystic. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:953–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunsting LA, Gockerman WH, O’Leary PA. Pyoderma (ecthyma) Gangrenosum clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1930;66:655–80. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shankar S, Sterling JC, Rybina E. Pustular pyoderma gangrenosum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:600–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caughman W, Stern R, Haynes H. Neutophilic dermatosis of myeloproliferative disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:751–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell FC, O’Kane M. Management of Pyoderma gangrenosum. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:347–55. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(01)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;484:1546–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TH, Oh SY, Myung SC. Pyoderma grangrenosum of the penis. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:1200–2. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.6.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parren LJ, Nellen R, van Marion AM, Henquet CJ, Frank J, Poblete-Gutierrez Penile pyoderma gangrenosum: Successful treatment with colchicines. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:7–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcovich S, Gatto A, Ferrara P, Garcovich A. Vulvar pyoderma gangrenosum in a child. Paediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:629–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho SA, Tan WP, Tan AW, Wong SN, Chua SH. Scrotal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn's disease. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:c397–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pallor SA, Sahn EE, Garen PD, Dobson RL, Chadwick EG. Pyoderma gangrenosum in paediatric acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Paediatr. 1990;117:63–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82444-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhat RM, Shetty SS, Kamath G.H. Pyoderma gangrenosum in childhood. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:205–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callen JP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Lancet. 1998;351:581–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paramkusam G, Meduri V, Gangashetty N. Pyoderma Gangrenosum with oral involvement: Case report and review of literature. Int J Oral Sci. 2010;2:111–6. doi: 10.4248/IJOS10032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadi BA, Lebwohl M. Clinical features of pyoderma gangrenosum and current diagnostic trends. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:950–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prystowsky JH, Kahn SN, Lazarus GS. Present status of pyoderma gangrenosum: Review of 21 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Von den Driesch P. Pyoderma gangrenosum: A report of 44 cases with follow- up. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:1000–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown TS, Marshall GS, Callen JP. Cavitating pulmonary infiltrate in an adolescent with pyoderma gangrenosum: A rarely recognized extracutaneous manifestation of a neutrophilic dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:108–12. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.103627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders S, Tahan SR, Kwan T, Magro CM. Giant cells in pyoderma gangrenosum. Cut Pathol. 2001;28:97–100. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.280206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talansky AL, Meyers S, Greenstein AJ, Janowetz HD. Does intestinal reaction heal pyoderma gangrenosum of inflammatory bowel disease? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1983;5:207–10. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198306000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chow KP, Ho CV. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:1047–60. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller J, Yentzer BA, Clark A, Jorizzo JL, Feldman SR. Pyoderma gangrenosum: A review and update on new therapies.J. Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:646–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhat RM. Management of pyoderma gangrenosum: An update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:329–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levell NJ, Skellett AM, Chriba M. Beclomethasone inhaler used to treat pyoderma gangrenosum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:337–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foneska HF, Ekanayake SM, Dissanayake M. Two percent topical phenytoin sodium solution in treating pyoderma gangrenosum: A cohort study. Int Wound J. 2010;7:519–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazokopakis EE, Kofteridis DP, Pateromihelaki AJ, Vytiniotis SD, Karastergiou PG. Improvement of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:134–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses: A review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:301–12. doi: 10.2165/11310730-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacob SE, Weisman RS, Kerdel FA. Pyoderma gangrenosum: Rebel without cure. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:192–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proudfoot LE, Singh S, Staughton RC. Superficial pyoderma gangrenosum responding to treatment with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1377–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]