Abstract

Patients with nocturia are often referred to urologists, but the underlying cause most often lies outside the urinary tract. Nocturia should be considered a systemic disorder and investigated and treated as such. Comprehensive assessment of the symptoms, optimally including a frequency volume chart, can help to determine the potential underlying cause and help to direct the patient to the most suitable medical professional for further management.

Although patients with nocturia are often referred to urologists, the underlying problem causing the problem most often lies outside the lower urinary tract. As such, it is more helpful to think of nocturia as a systemic disorder, rather than merely a lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS),1 and to select treatment based on a proper evaluation for contributory factors.

Assessment of nocturia

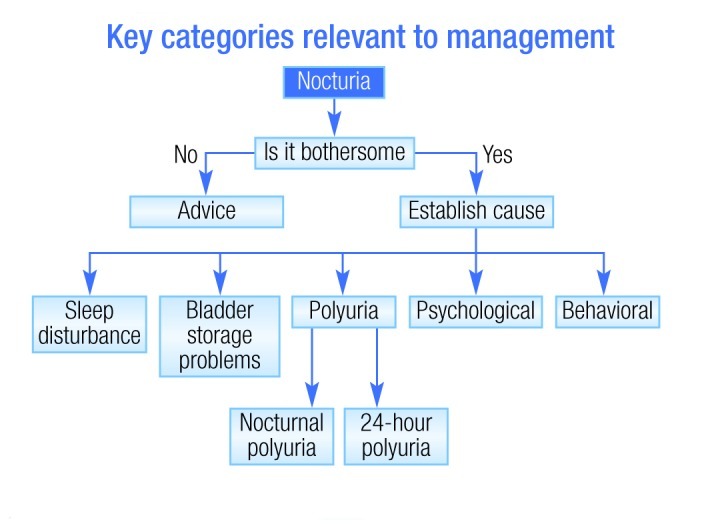

Assessment of nocturia should seek to categorize patients according to the presence or absence of sleep disturbance, bladder storage issues, polyuria, and psychological or behavioural influences (Fig. 1).2 A frequency volume chart is an indispensable tool to help characterize each individual patient’s problem.3

Fig. 1.

Investigating potential causes of nocturia. Adapted from Wein et al. Nocturia in men, women and the elderly: a practical approach. BJU Int 2002;90(Suppl3):28–31.

Management of nocturia

There has been a substantial body of research conducted using LUTS-specific pharmacotherapies for nocturia. Statistically significant symptom improvements from LUTS pharmacotherapy or surgery have been reported, but should be reviewed critically. The placebo-adjusted improvement in the number of voids with alpha-blockers, antimuscarinics, and 5-alpha reductase antagonists (alone or in combination) is in the range of 0.08 to 0.3 per night.4–11 Surgical management (prostatectomy) has been shown to reduce symptoms, but again, is far from curative. One analysis of prostatectomy showed that the nocturia frequency decreased from 3.4 preoperatively to 2.6 postoperatively.12 Nonetheless, it is doubtful whether this is clinically significant.

These minimal improvements with LUTS-specific treatments have helped to drive the recognition of nocturia as a systemic disorder, necessitating access to multimodal investigation and multi-disciplinary expertise, and obligates a shift away from a bias that the lower urinary tract is the main driver of nocturia. Other potential causes need to be investigated and treated when identified.

Patients with endocrine dysfunction

Nocturnal polyuria is potentially due to renal tubular13 or endocrine dysfunction and fluid shifts, leading to diuresis/natriuresis. Desmopressin is effective in some patients, and new data are emerging to guide safe dosing,14 including recognition of potential gender differences in response. Decrease in nocturnal urine volume in nocturia patients have been shown to be larger for women at lower desmopressin doses, and decreases in sodium greater in women over 50 years old than in men.15

Patients with sleep disturbances

Sleep disturbance can result from sleep disorders, medical/neurological/psychiatric disease and other influences, which need to be factored in by any urologist responsible for treating nocturia. Patients suspected of having a sleep disorder (e.g., sleep apnea, nocturnal seizures, excessive daytime sleepiness) should be referred to a sleep specialist.

In terms of therapy for sleep disturbances, an improvement in sleep hygiene (e.g., optimal room temperature, noise reduction, etc.) may be helpful for many patients. As a reflection of intrinsic circadian rhythm, the normal reduction in urine output during sleep is seen in alteration of key water-handling proteins of the kidney.16 Accordingly, the key circadian hormone, melatonin, was studied in 20 men with urodynamically confirmed bladder outflow obstruction and nocturia (three or more times per night).17 This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study assessing the effect of 2 mg controlled release melatonin at night. As shown in Table 1, a significantly greater proportion of patients responded to melatonin than to placebo, but responders were still in the minority in the active treatment group.

Table 1.

Melatonin for nocturia: Responder rates (by episodes reduced per night) in a randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study

| Responder definition | Melatonin | Placebo | P value | Mean bother reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.5 | 6 | 1 | 0.04 | 1.0 |

| −1.0 | 3 | 0 | 0.07 | 1.7 |

| −2.0 | 1 | 0 | 0.31 | 2.0 |

Adapted from Drake et al. Melatonin pharmacotherapy for nocturia in men with benign prostatic enlargement. J Urol 2004;171:1199–202.

Short-acting hypnotics may be helpful for patients with sleep disturbances. Oxazepam has been associated with a reduction in nocturia (but not nocturnal urine production).18

Global polyuria

For patients with global polyuria (>40 mL/kg/24h), the best approach may be behavioural modification (e.g., advise drinking to thirst, reduce salt intake). However, fluid restriction is not appropriate if an underlying cause of fluid loss is present, e.g., diabetes insipidus.

Nocturnal polyuria

Nocturnal polyuria may occur secondary to any renal tubular dysfunction, third space fluid sequestration, obstructive sleep apnea, circadian impairment or as a side effect of drugs (e.g., steroids).19

For those patients with suspected fluid sequestration (which is a possibility in patients with venous insufficiency, hypoalbuminemia, congestive cardiac failure, etc.), one can consider compression and elevation, or the use of a diuretic in the afternoon.20,21

Conclusions

The lower urinary tract is not the major cause of nocturia. One needs to assess the patient for underlying causes, recognizing that sleep disorders, polyuria and endocrine disease are the most likely causes. The management of nocturia may require a team approach, whenever possible, making optimal use of multidisciplinary expertise.

There is a need for better nocturia treatment algorithms based on screening measures and outcome prediction. Ultimately, these algorithms would incorporate simple screening measures to guide interdisciplinary referral and lead to the multidisciplinary teamwork that is required for full investigation and treatment success. This process should also help prevent the use of treatments for which symptomatic response cannot be anticipated.19

Footnotes

Competing interests: Prof. Drake is an ongoing paid consultant with Ferring. He has also received speaker fees, educational grants and/or travel assistance from Ferring, Allergan, Pfizer and Astellas within the last two years.

References

- 1.Gulur DM, Mevcha AM, Drake MJ. Nocturia as a manifestation of systemic disease. BJU Int. 2011;107:702–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wein A, Lose GR, Fonda D. Nocturia in men, women and the elderly: a practical approach. BJU Int. 2002;90(Suppl3):28–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.90.s3.8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss JP. Nocturia: “do the math.”. J Urol. 2006;175:S16–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson TM, 2nd, Jones K, Williford WO, et al. Changes in nocturia from medical treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: secondary analysis of the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Trial. J Urol. 2003;170:145–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000069827.09120.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Djavan B, Milani S, Davies J, et al. The Impact of Tamsulosin Oral Controlled Absorption System(OCAS) on Nocturia and the Quality of Sleep: Preliminary Results of a Pilot Study. Eur Urol Suppl. 2005;4:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eursup.2004.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson TM, 2nd, Burrows PK, Kusek JW, et al. The effect of doxazosin, finasteride and combination therapy on nocturia in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2007;178:2045–51. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi O, Marui E, Kakizaki H, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo- and propiverine-controlled trial of the once-daily antimuscarinic agent solifenacin in Japanese patients with overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2007;100:579–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brubaker L, FitzGerald MP. Nocturnal polyuria and nocturia relief in patients treated with solifenacin for overactive bladder symptoms. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:737–41. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0239-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nitti VW, Dmochowski R, Appell RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tolterodine extended-release in continent patients with overactive bladder and nocturia. BJU Int. 2006;97:1262–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rackley R, Weiss JP, Rovner ES, et al. Nighttime dosing with tolterodine reduces overactive bladder-related nocturnal micturitions in patients with overactive bladder and nocturia. Urology. 2006;67:731–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, et al. Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2319–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margel D, Lifshitz D, Brown N, et al. Predictors of nocturia quality of life before and shortly after prostatectomy. Urology. 2007;70:493–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda M, Motokawa M, Miyagi S, et al. Polynocturia in chronic kidney disease is related to natriuresis rather than to water diuresis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2172–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rembratt A, Riis A, Norgaard JP. Desmopressin treatment in nocturia; an analysis of risk factors for hyponatremia. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25:105–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juul KV, Klein BM, Sandström R, et al. Gender difference in antidiuretic response to desmopressin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F1116–22. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00741.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuber AM, Centeno G, Pradervand S, et al. Molecular clock is involved in predictive circadian adjustment of renal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16523–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904890106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drake MJ, Mills IW, Noble JG. Melatonin pharmacotherapy for nocturia in men with benign prostatic enlargement. J Urol. 2004;171:1199–202. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110442.47593.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaye M. Nocturia: a blinded, randomized, parallel placebo-controlled self-study of the effect of 5 different sedatives and analgesics. Can Urol Assoc J. 2008;2:604–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss JP, Ruud Bosch JL, Drake M, et al. Nocturia Think Tank: Focus on Nocturnal Polyuria. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:330–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.22219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynard J. A novel therapy for nocturnal polyuria: a double-blind randomized trial of furosemide against placebo. Br J Urol. 1998;82:932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedersen PA, Johansen PB. Prophylactic treatment of adult nocturia with bumetanide. Br J Urol. 1988;62:145–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1988.tb04294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]