Abstract

The objective of this study was to evaluate effects of genistein and moderate intensity exercise on Achilles tendon collagen and cross-linking in intact and ovariectomized (OVX) female Sprague-Dawley rats. Rats were separated into eight groups (n=9 per group): intact or OVX, treadmill exercised or sedentary, genistein-treated (300 mg•kg−1•day−1) or vehicle. After 6-weeks, tendons were assayed for the collagen-specific amino acid hydroxyproline and hydroxylyslpyridinoline (HP). Collagen content was not influenced by exercise (p=0.40) but was lower (p<0.001) in OVX vehicle rats compared to intact vehicle rats (OVX: 894±35 µg collagen/mg dry weight, intact: 1185±72 µg collagen/mg dry weight). In contrast, collagen content in OVX rats treated with genistein was greater (p=0.010, 1198±121 µg collagen/mg dry weight) when compared to untreated rats and not different from intact rats (p=0.89). HP content was lower in OVX genistein-treated when compared to intact genistein-treated rats, but only within the sedentary animals (p=0.05, intact-treated: 232±39mmol/mol collagen, OVX-treated: 144±21mmol/mol collagen). Our findings suggest that ovariectomy leads to a reduction in tendon collagen, which is prevented by genistein. HP content, however, may not have increased in proportion to the addition of collagen. Genistein may be useful for improving tendon collagen content in conditions of estrogen deficiency.

Keywords: hydroxyproline, hydroxylyslpyridinoline, ovariectomized, exercise, phytoestrogen

Introduction

It is well documented that the loss of estrogen associated with post menopause results in an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and sarcopeniain women (Dionne et al. 2000; Maltais et al. 2009; Subbiah 2002). There is also recent evidence demonstrating that estrogen can influence tendon extracellular matrix (ECM), specifically collagen synthesisin women (Cook et al. 2007; Hansen et al. 2009; Hansen et al. 2008; Hansen et al. 2009). Indeed, in vitro studies of tendon fibroblasts suggest that estrogen deficiency may decrease collagen turnover (Irie et al. 2010) and tendon collagen synthesis is lower in post-menopausal women not taking estrogen therapy (ET) (Hansen et al. 2009). In experimental studies using the ovariectomized (OVX) rat the activity of the ECM degrading protein matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 is increased in tendon (Pereira et al. 2010), which has been associated with a decrease in collagen content in some tissues (Jackson et al. 2002). Supporting this hypothesis, a significant decrease in type I collagen content has been documented in non-tendon connective tissue in post-menopausal women (Moalli et al. 2004). Estrogen also appears to activate lysyl oxidase (Sanada et al. 1978), the enzyme regulating the addition of lysine and hydroxylysine-based cross-links into collagen fibrils (Eyre et al. 1984). Therefore, a lack of estrogen could alter collagen and/or cross-linking content of tendon, both of which are important for maintaining the tendon tensile strength and stiffness (Chan et al. 1998; Franchi et al. 2007).

Although ET is used as a substitute therapy to counter the natural loss of circulating estrogen levels in postmenopausal women (Ronkainen et al. 2009), this form of therapy is often associated with significant adverse health effects including increased incidence of coronary artery disease (Hulley et al. 1998; Manson et al. 2003) and certain cancers (Chen 2011; Furness et al. 2009). Genistein, a naturally occurring isoflavone phytoestrogen, has structural similarities to estrogen, and has been shown to bind to estrogen receptors (Casanova et al. 1999). We have demonstrated that short-term genistein treatment reduces arterial blood pressure and heart rate (Al-Nakkash et al. 2010) and increases cardiac ischemic tolerance in the OVX rat (Al-Nakkash et al. 2009). Thus, genistein has been promoted as an alternative to ET due to its beneficial effects on cardiovascular and reproductive health without the unequivocal effects on the female reproductive system (Anthony et al. 1996) or cancer incidence (Sliva 2008). Whether genistein treatment produces favorable effects on tendon collagen or cross-linking in the OVX rat remains to be determined.

Moderate intensity exercise is generally recommended for postmenopausal women to help maintain bone mass, reduce the risk of metabolic diseases, and improve quality of life (Kohrt et al. 2004). Whether exercise stimulates tendon collagen synthesis in women is still debatable, as studies have shown that exercise may (Hansen et al. 2008) or may not (Hansen et al. 2009; Miller et al. 2007) increase tendon collagen synthesis. Additionally, in young women tendon adaptations to exercise appear to be blunted when compared to males (Magnusson et al. 2007). In contrast, the effects of chronic exercise on tendon adaptations have not been extensively explored in estrogen deficient females. Furthermore, no studies to date have evaluated the combined effects of genistein treatment and exercise on tendon structural properties in estrogen deficit females. Therefore, in this study, we have evaluated the effect of ovariectomy and genistein treatment with or without treadmill exercise on Achilles tendon collagen content and hydroxylyslpyridinoline (HP) cross-linking in female Sprague-Dawley rats. We hypothesized that ovariectomy would lead to a reduction in tendon collagen content and HP cross-linking and that genistein treatment and/or treadmill exercise would prevent any changes in collagen or HP cross-linking induced by ovariectomy.

MATERIALS AND Methods

Study Protocol

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (n=72) were purchased (200–300 grams, Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) as either OVX or intact. These rats were randomly placed into vehicle orgenistein-treated groups, then subdivided further into sedentary or exercise groups (Table 1). Animals were surgically implanted with a subcutaneous constant day-release pellet (300 mg genistein•kg body weight−1•day−1) or placebo (vehicle) pellet. Rats in the exercise groups completed treadmill running (Columbus Instruments Exer 3/6 treadmill, Columbus, Ohio) five days per week for six weeks. Exercise was progressed from 10 minutes to 30 minutes by adding five minutes per week. Speed was maintained at 15 meters•minute−1(~60% of estimated maximal oxygen uptake) for the first three weeks then increased to 20 meters•minute−1(~80% of maximal oxygen uptake) for the remaining three weeks (Hoydal et al. 2007; Wisloff et al. 2001). Rats were caged in pairs, allowed access to genistein-free food (a specially formulated casein-based diet (Al-Nakkash et al. 2006), DyetsInc, Bethlehem, PA), and water ad libitum, and maintained on a 12-hour light-dark cycle. This investigation was approved by the Midwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and all animals were cared for in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Nation Research Council 2011).

Table 1.

Groups Assignments

| Ovary Status | Physical Activity | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Intact | Sedentary | Vehicle |

| Genistein | ||

| Exercise | Vehicle | |

| Genistein | ||

| Ovariectomized | Sedentary | Vehicle |

| Genistein | ||

| Exercise | Vehicle | |

| Genistein |

Female Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized into a total of 8 groups (n=9/group) according to presence/absence of ovaries, 6 week of exercise or sedentary lifestyle, and 6 weeks of 300 mg•kg−1•day−1 genistein constant regime pellet supplementation or empty control vehicle.

Tissue Analysis

After the completion of the 6-week treatment period animals were euthanized and Achilles tendons were carefully extracted and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Prior to the analysis of collagen and HP crosslinks, a 5–10 mg portion of the tendon was freeze dried for 36 hours and then reweighed to obtain tendon dry weight. Samples were then hydrolyzed for 24 hours at 100°C in 6 N HCl (Carroll et al. 2012).

Collagen Analysis

Tendon collagen concentration was determined by quantification of the collagen specific amino acid hydroxyproline (HYP) by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and fluorometric detection, as we have previously described (Carroll et al. 2012). Briefly, derivatized samples were injected onto an HPLC (LC-20AB and SIL-20, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA) and separation of HYP was achieved via an XTerra RP 18, 5 µm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) using an isocratic mobile phase of 35% acetonitrile and 65% acetic acid (3% glacial acetic acid, sodium acetate buffered to pH 4.3) at a 1.0 ml•min−1 flow rate. Peaks were monitored at 260 nm excitation/316 nm emission (RF-10AXL, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments) and integrated with chromatography software (LC Solution Ver. 1.2, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA).

Collagen Cross-linking Analysis

Hydroxylyslpyridinoline concentrations were determined using HPLC, as we have previously described (Carroll et al. 2012). A 500 µL aliquot of the hydrolyzed sample (see Collagen Analysis) was evaporated to dryness overnight at ambient temperature (Thermo Fisher Scientific Savant SPD131DDA SpeedVac Concentrator, www.fishersci.com), reconstituted in cross-link buffer (0.5% (v/v) heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) in 10% acetonitrile), and injected into the HPLC system described above. Samples were compared to known HP standards (PYD/DPD HPLC Calibrator, 8004, Quidel Corp., San Diego, CA, USA). Separation was achieved with a Restek RP C18, 5 µm, 150 × 4.0 mm ID column (9174564, Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA) using an isocratic method [mobile phase A (0.13% HFBA) and mobile phase B (0.13% HFBA, 75% acetonitrile)]. Samples were eluted using 17% mobile phase B from 0–17 minutes, followed by 100% mobile phase B for a 5-minute wash. The column was then re-equilibrated with 17% mobile phase B for 8 minutes prior to the next injection. A flow rate of 1.0 mL/min was used. Fluorescence was monitored at 295 nm excitation/395 nm emission and peaks were integrated with chromatography software (LC Solution Ver. 1.2).

Statistics

Animal body weight was evaluated with a balanced two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) while all other variables were evaluated with a balanced three-way ANOVA [exercise (sedentary vs. exercise), treatment (vehicle vs. genistein), and condition (intact vs. OVX)]. The Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test was used to explore differences when a significant interaction was detected. Values were considered significant at an alpha level of p<0.05. All data are expressed as mean±standard error. All data were analyzed using SigmaPlot Version 11 (Systat Software, Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Body Weight

The effects of ovariectomy, genistein treatment, and exercise training on body weight are shown in Table 2. Body weight increased in all groups (p<0.001) during the 6-week intervention. A significant main effect for condition (intact vs. OVX) was detected (p<0.001). Post hoc testing indicated that the OVX rats treated with vehicle weighed significantly more than intact animals independent of exercise training.

Table 2.

Animal Body Weights

| IVS | IVE | IGS | IGE | OVS† | OVE† | OGS | OGE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Body Weight (g) | 240±10 | 228±8 | 232±15 | 237±15 | 274±10 | 284±12 | 245±5 | 261±14 |

| Final Body Weight (g) | 269±12* | 268±8* | 263±16* | 264±11* | 318±9* | 327±6* | 307±8* | 300±10* |

p<0.001, main effect increase with time in all groups.

p<0.001, main effect for condition (intact vs. OVX), OVS and OVE greater than all intact groups. Intact (I), Ovariectomized (O), Vehicle (V), Genistein (G), Sedentary (S), Exercise (E). n=9 animals per group.

Collagen and Tissue Water Content

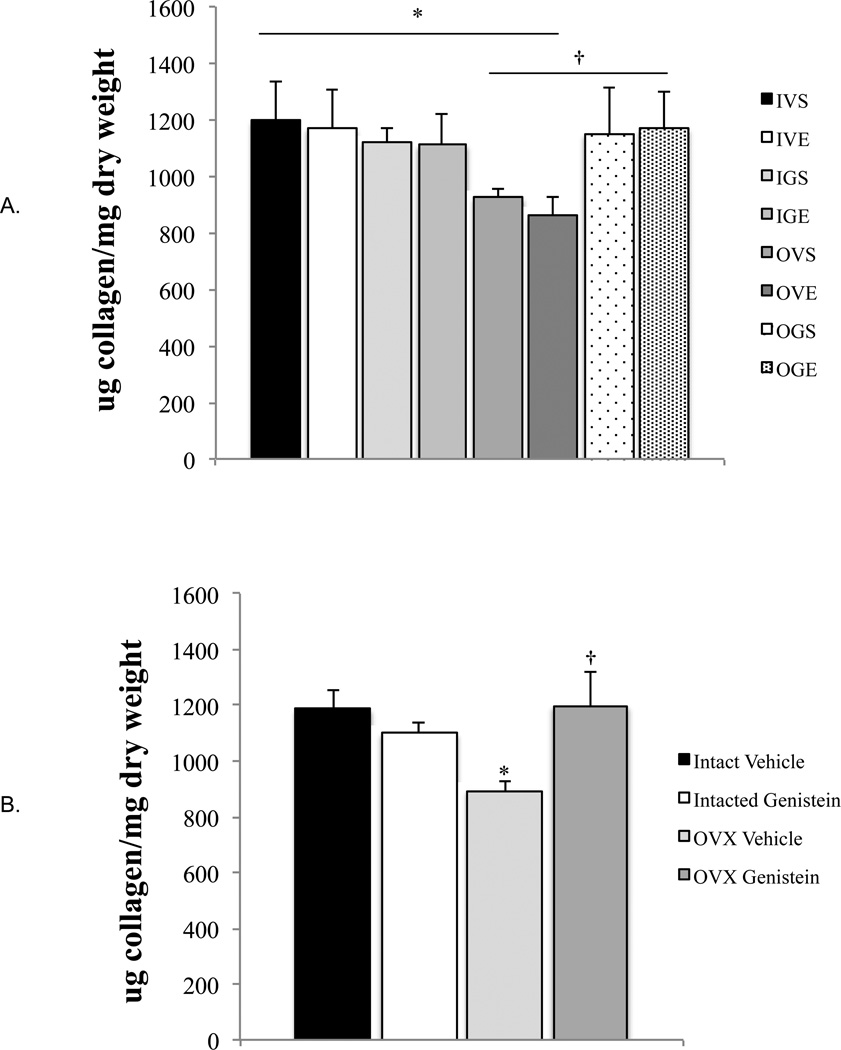

Tissue water content was not influenced by exercise, ovariectomy, or treatment with genistein (p=0.61; Figure 1), thus all collagen data are expressed relative to tissue dry weight. Tendon collagen content was not influenced by exercise (Figure 2) and no significant three-way interaction was detected (p=0.40). There was, however, a significant two-way interaction (p=0.025, Figure 2b) for condition (intact vs. OVX) × treatment (vehicle vs. genistein). The post-hoc analysis of this two-way interaction indicated that: 1) in OVX-vehicle rats, tendon collagen content was 28% lower compared to intact-vehicle animals (OVX: 894±35 µg collagen•mg dry weight−1, intact: 1185±72 µg collagen•mg dry weight−1, p<0.001, Figure 2b), 2) treatment with genistein did not altercollagen content in intact animals (intact-vehicle: 1185±72 µg collagen•mg dry weight−1, intact-genistein: 1099±42 µg collagen•mg dry weight−1,p=0.55, Figure 2b) and 3) OVX animals treated with genistein had greater collagen content (Figure 2b) than untreated OVX animals (OVX-gensitein: 894±35 µg collagen•mg dry weight−1, OVX-vehicle: 1198±121 µg collagen•mg dry weight−1, p=0.010) weight.

Figure 1.

Achilles tendon water content (percentage of total tissue weight). Intact (I), Ovariectomized (O), Vehicle (V), Genistein (G), Sedentary (S), Exercise (E). Data presented as mean±standard error.

Figure 2.

Achilles tendon collagen content normalized to tendon dry weight. a) All groups. Intact (I), Ovariectomized (O), Vehicle (V), Genistein (G), Sedentary (S), Exercise (E). Each bar represents n=9; b) Data highlighting two-way [condition (intact vs. ovariectomized) × treatment (vehicle vs. genistein)] interaction. Each bar represents n=18. *p<0.001, Intact-Vehicle vs. OVX-Vehicle. †p≤0.010, OVX-Vehicle vs. OVX-Genistein. Ovariectomized (OVX). Data presented as mean±standard error.

Collagen HP Cross-linking

A significant (p=0.014) three-way interaction was detected for HP cross-linking with post-hoc testing indicating a condition (intact vs. OVX) × treatment (vehicle vs. genistein) interaction within the sedentary animals (p=0.05, Figure 3a). Specifically, HP cross-linking was lower in genistein-treated OVX rats when compared to intact rats (Figure 3a) but only when considering the sedentary animals. There was an opposite trend in the exercise animals, i.e. HP cross-linking was greater in genistein treated OVX animals when compared to untreated animals but lower in intact treated animals compared to untreated intactrats (Figure 3b). This difference, however, did not reach statistical significance (p=0.12).

Figure 3.

Achilles tendon hydroxylyslpyridinoline (HP) normalized to collagen content. a) plot of the two-way [condition (intact vs. ovariectomized) × treatment (vehicle vs. genistein)] interaction (*p=0.052) within the sedentary rats. b) plot of the two-way [condition (intact vs. ovariectomized) × treatment (vehicle vs. genistein)] interaction (†p=0.119) within the exercise rats. Data presented as mean±standard error.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first investigation to examine the interactive effect of ovariectomy, genistein treatment, and exercise training on collagen and HP cross-linking content of tendon. Neither moderate intensity physical training nor genistein treatment had an influence on Achilles tendon collagen content in intact animals. In contrast, our results show that ovariectomy resulted in a substantial decrease in Achilles tendon collagen content, which was prevented by genistein treatment. The lack of an effect of genistein in intact animals suggests that genistein supplementation in young females may not have the negative effects on tendon often associated with exogenous estrogen given to young females (Hansen et al. 2008; Hansen et al. 2009). These data are also consistent with in vitro studies demonstrating no effect of physiological estrogen levels on fibroblast collagen synthesis (Seneviratne et al. 2004). We also observed a trend (p=0.05, Figure 2a) for collagen HP cross-linking content to be lower in sedentary genistein-treated OVX rats, suggesting that the addition of HP cross-links may not have been proportional to the addition of collagen with genistein treatment in these animals. Exercise, however, seemed to normalize HP cross-link content in genistein-treated OVX rats (Figure 2b). The observed effect of genistein on tendon collagen in OVX rats is considerable and suggests that the further study of genistein as a beneficial therapy for conditions of estrogen-deficiency is warrented.

The only known enzyme regulating the addition of HP cross-links into collagen fibrils, lysyl oxidase, has been shown to be activated by estrogen in skin and bone (Sanada et al. 1978). Our data, however, suggest that the presence of estrogen is not an absolute requirement to maintain the appropriate ratio of HP cross-links per collagen molecule, i.e. HP cross-linking likely decreased in proportion to the decrease in collagen content with ovariectomy. Although genistein treatment increased collagen content in OVX animals, cross-linking may not have increased in proportion to the addition of collagen, at least in sedentary animals. It is possible that the enhancement of collagen production by genistein also altered the fibril diameter distribution in favor of smaller diameter fibrils, as seen with estrogen therapy (Hansen et al. 2009), which could reduce the possibility for establishment of intra-molecular cross-links. A longer treatment regimen or the addition of exercise may be needed to increase HP cross-linking in proportion to collagen in OVX animals treated with genistein.

The lack of an observed effect of exercise training on collagen and HP cross-linking content in our intact animals could be due to the intensity of exercise training or the sex of the animals. Several studies (Magnusson et al. 2007; Miller et al. 2007) have demonstrated that the ability of tendon to adapt to exercise is blunted in females and our findings would seem to confirm these data. Additionally, the intensity and/or duration of exercise training may not have been adequate to induced changes in tendon structural properties. Using a treadmill protocol of higher intensity and longer duration (60 minutes per day for 8 weeks) we have recently demonstrated that chronic treadmill exercise increases Achilles tendon collagen HP cross-linking but not collagen content in male rats (Carroll et al. 2012).

In line with our hypothesis, ovariectomy resulted in a substantial decline in tendon collagen content and this effect was prevented by administration of genistein. The decline in tendon collagen is consistent with previous studies in non-tendon connective tissue where type I collagen content was reduced (Moalli et al. 2004) and MMP-2 activity increased (Pereira et al. 2010) in estrogen-deficient states. Tendon strain for a given stress is higher in females compared to males regardless of age (Carroll et al. 2008). A decline in collagen content in postmenopausal women could result in a weakened tendon (Davison 1989) and even greater strain at a given stress, which may increase the tendon’s susceptibility to strain injury (Magnusson et al. 2007; Riley 2008; Wang et al. 2006).

The ability of genistein to enhance collagen content in the OVX rat is substantial given the fact that the rats were treated for a period of only 6 weeks. Although future studies are needed to define the mechanism(s) by which genistein influences tendon ECM, tendons do express estrogen receptors (Sciore et al. 1998) and genistein is known to bind estrogen receptors and have estrogenic effects on other tissues (So et al. 1997; Suetsugi et al. 2003; Tissier et al. 2007; Zava et al. 1997). In heart tissue, estrogen treatment has been shown to decrease MMP-9 activation and reduce collagen accumulation in volume-overload hearts of OVX rats (Voloshenyuk et al. 2010), suggesting that genistein may have decreased the increase in MMP activity associated with ovariectomy (Pereira et al. 2010). Genistein may also directly influence collagen synthesis. For example, in a model of oxidative stress were collagen synthesis is suppressed, genistein treatment prevented the oxidant induced decrease in collagen synthesis (Sienkiewicz et al. 2008). The effect of genistein on collagen synthesis may be via the IGF-1 signaling pathway, an important growth factor regulating collagen synthesis (Murphy et al. 1997). In studies of human fibroblasts, genistein has been shown to upregulate insulin-like growth receptor protein expression (Sienkiewicz et al. 2008). Additionally, in contrast to estrogen therapy (Hansen et al. 2009), which decreases IGF-1 bioavailabity, genistein treatment increases serum IGF-1 in postmenopausal women (Marini et al. 2007). These differences between gensitein and estrogen highlight the need for additional studies evaluating the mechanism(s) by which genistein influences tendon collagen.

Interestingly, genistein appears to reduce collagen accumulation (i.e., fibrosis) in the heart (Mizushige et al. 2007; Voloshenyuk & Gardner 2010) and lung (Day et al. 2008) in pathological states. Furthermore, in contrast to tendon, collagen content is elevated in some connective tissues in post-menopausal women (Falconer et al. 1996), suggesting either a tissue specific effect of estrogen deficiency and genistein action and/or a different mechanisms of action on collagen metabolism in healthy versus diseased states.

PERSPECTIVE

In summary, we demonstrate that genistein treatment may be an effective means to prevent a decline in tendon collagen content in a rat model of the postmenopausal state. Moreover, our findings confirm that estrogen is an absolute requirement for maintaining normal levels of tendon collagen in females. As the most abundant protein in mammals, collagen is an important component of many tissues and is the predominant protein in tendon. Collagen is also an important constituent of bone, skeletal muscle, and heart, thus our findings may have implications for these tissues. The lower HP content in the OVX-treated sedentary rats suggests that the addition of HP cross-links may not have been proportional to the addition of collagen in these animals. Exercise, however, seemed to normalize HP cross-linking in genistein-treated OVX rats. The ability of genistein to prevent declines in tendon collagen may have important implications for post-menopausal women and our findings continue to support the potential health benefits of genistein consumption. Futures studies are needed to evaluate the functional implications of genistein’s effect on tendon and whether these effects extend to other tissues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Jamie Tedeschi for assistance with animal training and Jason Kamilar, PhD for statistical guidance. Funding Support: Midwestern University Kenneth A. Suarez Summer Research Fellowship to J.E. Ramos and M.S. Moore, College of Health Sciences, Midwestern University Intramural Awards to C.C. Carroll and T.L. Broderick, and NIH 1R15DK071625-01A2 to L. Al-Nakkash.

REFERENCES

- Al-Nakkash L, Clarke LL, Rottinghaus GE, Chen YJ, Cooper K, Rubin LJ. Dietary genistein stimulates anion secretion across female murine intestine. J Nutr. 2006;136:2785–2790. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.11.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nakkash L, Markus B, Batia L, Prozialeck WC, Broderick TL. Genistein induces estrogen-like effects in ovariectomized rats but fails to increase cardiac GLUT4 and oxidative stress. J Med Food. 2010;13:1369–1375. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nakkash L, Markus B, Bowden K, Batia LM, Prozialeck WC, Broderick TL. Effects of acute and 2-day genistein treatment on cardiac function and ischemic tolerance in ovariectomized rats. Gend Med. 2009;6:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony MS, Clarkson TB, Hughes CL, Jr, Morgan TM, Burke GL. Soybean isoflavones improve cardiovascular risk factors without affecting the reproductive system of peripubertal rhesus monkeys. J Nutr. 1996;126:43–50. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll CC, Dickinson JM, Haus JM, Lee GA, Hollon CJ, Aagaard P, Magnusson SP, Trappe TA. Influence of aging on the in vivo properties of human patellar tendon. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1907–1915. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00059.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll CC, Whitt JA, Peterson A, Gump BS, Tedeschi J, Broderick TL. Influence of acetaminophen consumption and exercise on Achilles tendon structural properties in male Wistar rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R990–R995. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00659.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova M, You L, Gaido KW, Archibeque-Engle S, Janszen DB, Heck HA. Developmental effects of dietary phytoestrogens in Sprague-Dawley rats and interactions of genistein and daidzein with rat estrogen receptors alpha and beta in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 1999;51:236–244. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/51.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan BP, Fu SC, Qin L, Rolf C, Chan KM. Pyridinoline in relation to ultimate stress of the patellar tendon during healing: an animal study. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:597–603. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: current status and unanswered questions. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:509–518. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JL, Bass SL, Black JE. Hormone therapy is associated with smaller Achilles tendon diameter in active post-menopausal women. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17:128–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council NR. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison PF. The contribution of labile crosslinks to the tensile behavior of tendons. Connect Tissue Res. 1989;18:293–305. doi: 10.3109/03008208909019078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RM, Barshishat-Kupper M, Mog SR, McCart EA, Prasanna PG, Davis TA, Landauer MR. Genistein protects against biomarkers of delayed lung sequelae in mice surviving high-dose total body irradiation. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2008;49:361–372. doi: 10.1269/jrr.07121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne IJ, Kinaman KA, Poehlman ET. Sarcopenia and muscle function during menopause and hormone-replacement therapy. J Nutr Health Aging. 2000;4:156–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre DR, Paz MA, Gallop PM. Cross-linking in collagen and elastin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:717–748. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer C, Ekman-Ordeberg G, Ulmsten U, Westergren-Thorsson G, Barchan K, Malmstrom A. Changes in paraurethral connective tissue at menopause are counteracted by estrogen. Maturitas. 1996;24:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(96)82010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi M, Trire A, Quaranta M, Orsini E, Ottani V. Collagen structure of tendon relates to function. Scientific World Journal. 2007;7:404–420. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness S, Roberts H, Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A, Hickey M, Farquhar C. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women and risk of endometrial hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000402.pub3. CD000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Kongsgaard M, Holm L, Skovgaard D, Magnusson SP, Qvortrup K, Larsen JO, Aagaard P, Dahl M, Serup A, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Langberg H, Kjaer M. Effect of estrogen on tendon collagen synthesis, tendon structural characteristics, and biomechanical properties in postmenopausal women. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1385–1393. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90935.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Koskinen SO, Petersen SG, Doessing S, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Westh E, Magnusson SP, Kjaer M, Langberg H. Ethinyl oestradiol administration in women suppresses synthesis of collagen in tendon in response to exercise. J Physiol. 2008;586:3005–3016. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Miller BF, Holm L, Doessing S, Petersen SG, Skovgaard D, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Koskinen S, Pingel J, Kjaer M, Langberg H. Effect of administration of oral contraceptives in vivo on collagen synthesis in tendon and muscle connective tissue in young women. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1435–1443. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90933.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoydal MA, Wisloff U, Kemi OJ, Ellingsen O. Running speed and maximal oxygen uptake in rats and mice: practical implications for exercise training. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:753–760. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3281eacef1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, Furberg C, Herrington D, Riggs B, Vittinghoff E. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie T, Takahata M, Majima T, Abe Y, Komatsu M, Iwasaki N, Minami A. Effect of selective estrogen receptor modulator/raloxifene analogue on proliferation and collagen metabolism of tendon fibroblast. Connect Tissue Res. 2010;51:179–187. doi: 10.3109/03008200903204669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S, James M, Abrams P. The effect of oestradiol on vaginal collagen metabolism in postmenopausal women with genuine stress incontinence. BJOG. 2002;109:339–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt WM, Bloomfield SA, Little KD, Nelson ME, Yingling VR. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand: physical activity and bone health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1985–1996. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000142662.21767.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson SP, Hansen M, Langberg H, Miller B, Haraldsson B, Westh EK, Koskinen S, Aagaard P, Kjaer M. The adaptability of tendon to loading differs in men and women. Int J Exp Pathol. 2007;88:237–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltais ML, Desroches J, Dionne IJ. Changes in muscle mass and strength after menopause. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2009;9:186–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson JE, Hsia J, Johnson KC, Rossouw JE, Assaf AR, Lasser NL, Trevisan M, Black HR, Heckbert SR, Detrano R, Strickland OL, Wong ND, Crouse JR, Stein E, Cushman M. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:523–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini H, Minutoli L, Polito F, Bitto A, Altavilla D, Atteritano M, Gaudio A, Mazzaferro S, Frisina A, Frisina N, Lubrano C, Bonaiuto M, D'Anna R, Cannata ML, Corrado F, Adamo EB, Wilson S, Squadrito F. Effects of the phytoestrogen genistein on bone metabolism in osteopenic postmenopausal women: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:839–847. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BF, Hansen M, Olesen JL, Schwarz P, Babraj JA, Smith K, Rennie MJ, Kjaer M. Tendon collagen synthesis at rest and after exercise in women. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:541–546. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00797.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushige T, Mizushige K, Miyatake A, Kishida T, Ebihara K. Inhibitory effects of soy isoflavones on cardiovascular collagen accumulation in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2007;53:48–52. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.53.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moalli PA, Talarico LC, Sung VW, Klingensmith WL, Shand SH, Meyn LA, Watkins SC. Impact of menopause on collagen subtypes in the arcus tendineous fasciae pelvis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DJ, Nixon AJ. Biochemical and site-specific effects of insulin-like growth factor I on intrinsic tenocyte activity in equine flexor tendons. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira GB, Prestes J, Leite RD, Magosso RF, Peixoto FS, Marqueti Rde C, Shiguemoto GE, Selistre-de-Araujo HS, Baldissera V, Perez SE. Effects of ovariectomy and resistance training on MMP-2 activity in rat calcaneal tendon. Connect Tissue Res. 2010;51:459–466. doi: 10.3109/03008201003676330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley G. Tendinopathy--from basic science to treatment. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:82–89. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronkainen PH, Kovanen V, Alen M, Pollanen E, Palonen EM, Ankarberg-Lindgren C, Hamalainen E, Turpeinen U, Kujala UM, Puolakka J, Kaprio J, Sipila S. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy modifies skeletal muscle composition and function: a study with monozygotic twin pairs. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:25–33. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91518.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanada H, Shikata J, Hamamoto H, Ueba Y, Yamamuro T, Takeda T. Changes in collagen cross-linking and lysyl oxidase by estrogen. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;541:408–413. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciore P, Frank CB, Hart DA. Identification of sex hormone receptors in human and rabbit ligaments of the knee by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction: evidence that receptors are present in tissue from both male and female subjects. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:604–610. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratne A, Attia E, Williams RJ, Rodeo SA, Hannafin JA. The effect of estrogen on ovine anterior cruciate ligament fibroblasts: cell proliferation and collagen synthesis. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1613–1618. doi: 10.1177/0363546503262179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sienkiewicz P, Surazynski A, Palka J, Miltyk W. Nutritional concentration of genistein protects human dermal fibroblasts from oxidative stress-induced collagen biosynthesis inhibition through IGF-I receptor-mediated signaling. Acta Pol Pharm. 2008;65:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliva D. Suppression of cancer invasiveness by dietary compounds. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2008;8:677–688. doi: 10.2174/138955708784567412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So FV, Guthrie N, Chambers AF, Carroll KK. Inhibition of proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive MCF-7 human breast cancer cells by flavonoids in the presence and absence of excess estrogen. Cancer Lett. 1997;112:127–133. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(96)04557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiah MT. Estrogen replacement therapy and cardioprotection: mechanisms and controversies. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2002;35:271–276. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2002000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetsugi M, Su L, Karlsberg K, Yuan YC, Chen S. Flavone and isoflavone phytoestrogens are agonists of estrogen-related receptors. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:981–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissier R, Waintraub X, Couvreur N, Gervais M, Bruneval P, Mandet C, Zini R, Enriquez B, Berdeaux A, Ghaleh B. Pharmacological postconditioning with the phytoestrogen genistein. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voloshenyuk TG, Gardner JD. Estrogen improves TIMP-MMP balance and collagen distribution in volume-overloaded hearts of ovariectomized females. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R683–R693. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00162.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JH, Iosifidis MI, Fu FH. Biomechanical basis for tendinopathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:320–332. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000195927.81845.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisloff U, Helgerud J, Kemi OJ, Ellingsen O. Intensity-controlled treadmill running in rats: VO (2 max) and cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1301–H1310. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zava DT, Blen M, Duwe G. Estrogenic activity of natural and synthetic estrogens in human breast cancer cells in culture. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(Suppl 3):637–645. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]