Abstract

The Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 presents an opportunity to change the nutritional quality of foods served in low-income childcare centers, including Head Start centers.

Excessive fruit juice consumption is associated with increased risk for obesity. Moreover, there is recent scientific evidence that sucrose consumption without the corresponding fiber, as is commonly present in fruit juice, is associated with the metabolic syndrome, liver injury, and obesity.

Given the increasing risk of obesity among preschool children, we recommend that the US Department of Agriculture’s Child and Adult Food Care Program, which manages the meal patterns in childcare centers such as Head Start, promote the elimination of fruit juice in favor of whole fruit for children.

CHILDHOOD OBESITY HAS reached epidemic proportions in the United States. By age four, 18.4% of all children are obese, with a body mass index (BMI; defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) in the 95th percentile or greater for age and gender. There is an even greater prevalence among Hispanic (22.0%), American Indian or Alaska Native (31.2%), and non-Hispanic Black children (20.8%) than among non-Hispanic White children.1 Among older children, the greatest increase in the prevalence of obesity has been in those in low-education, -income, and -employment households that have sustained increases from 22% to 33% from 2003 to 2008.2 Per capita daily caloric intake increases in beverages, particularly sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices, parallel the surge in childhood obesity in the United States.3 Additionally, studies document the association between excessive consumption of fruit juice and an increased risk for childhood obesity and short stature.4

To address the obesity epidemic in children and the simultaneous increase in caloric intake from beverages, the Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children changed the food package in 2009 for the high-risk children who the program serves to eliminate fruit juice for infants younger than 12 months and to limit juice consumption to less than four ounces a day for children older than one year.5 In this article, we have argued that the rapid increase in obesity among American children necessitates a more aggressive approach, for example, to limit high caloric beverages such as 100% fruit juice, particularly among young children, who are first developing eating behaviors and practices.

A unique opportunity to reshape the eating and drinking habits of high-risk US children presents itself in the forms of the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act and the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act.6 The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act is designed to target the nutritional health of high-risk, low-income children younger than five years, including those participating in the Child and Adult Food Care Program (CAFCP), which includes Head Start and other low-income daycare centers. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) is mandated to develop, as early as fall 2013, updated meal patterns and nutrition standards for CAFCP meals and snacks that reflect current relevant science.7 Additionally, the secretary of agriculture is required to provide nutrition guidance to childcare centers and states by January 1, 2012, to ensure increased consumption of such foods as fresh, canned, and frozen fruits.7

We recommend that the CAFCP meal patterns and nutrition standards include the removal of 100% fruit juice from the CAFCP programs to counter increases in fruit juice consumption among US preschool children and in line with recent science that underscores the danger of fructose consumption without concurrent fiber in contributing to childhood obesity. Our recommendations also parallel the act’s mandate that only low-fat milk options be served to children older than two years, that water be made readily available and accessible,7 and that CAFCP programs adhere to the limits placed on 100% fruit juice by professional organizations and institutes in the past 10 years.

PRESCHOOL CHILDREN’S INCREASED FRUIT JUICE CONSUMPTION

US children have increasing per capita daily caloric contribution from sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juice.3 Toddlers and young children have the highest consumption of fruit juice of all age groups in the United States.8 Fruit juices and flavored drinks are the second and third largest contributors to energy intake among toddlers.9 Total consumption of fruit juice is also high among preschool children.

An analysis of National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey data from 1999 to 2004 reveals that preschool children (aged two to five years) who drink 100% fruit juice consume an average of 10 ounces or more daily.3 Meanwhile preschool children are not meeting the recommendations for milk10 or fiber intake.11 Similarly, the Feeding Infants and Toddlers study found 40% to 60% of toddlers did not have fruit at breakfast, lunch, or dinner to meet the five-a-day requirement.12 After the transition to adult table foods, consumption of fruit decreases; one third of children aged 19 to 24 months never consume fruit.13

100% FRUIT JUICE IS NEVER THE SAME AS WHOLE FRUIT

Consumption of fruit juice by children is problematic because of its high sugar content and low levels of fiber. For example, four ounces of 100% apple juice has 0 grams of fiber but 13 grams of sugar for 60 calories.14 Similarly, 100% grape juice has 20 grams of sugar per four fluid ounces. Correspondingly, one half cup of sliced apples has half as many calories (30) and fewer calories from sugar (5.5 g) and the addition of 1.5 grams of fiber. US children’s overall consumption of fiber is low,11 although increased consumption of fiber is associated with a reduced risk for obesity in both children and adults.15,16 Dietary fiber intake in high-risk youths is inversely related to visceral adiposity.17

Moreover, recent data suggest that excessive fructose consumption, either from the sucrose (approximately 50% fructose) in 100% fruit juice or from high-fructose corn syrup in sweetened beverages, may be associated with liver injury and the metabolic syndrome.18 Hepatic metabolism of fructose promotes fat development and storage of intrahepatic lipids, inhibition of mitochondrial β-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids, triglyceride formation and steatosis, liver and skeletal muscle insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia.18 Longitudinal intervention studies have shown that hypercaloric diets of both fat and fructose can increase intrahepatocellular lipids, and those of fructose alone stimulate very low-density lipoprotein triacylglycerols.19

Data also suggest that liquid calories may fail to trigger physiological satiety mechanisms as solid foods do, also implicating 100% fruit juices—even those with added fiber—in the obesity epidemic.20,21 Conversely, although whole fruit also has fructose, the fiber present in whole fruit limits the insulin response and increases satiety.22 Fruit juice may alter nervous system energy signaling, resulting in dependence and habituation, which is associated with overconsumption and the metabolic syndrome.23

Although the 100% fruit juice industry might be inclined to simply add fiber to fruit juice to address consumer complaints as some brands have done, it is imperative to emphasize that fruit juice with added fiber cannot be equated with whole fruit. Liquid calories do not trigger the same physiological response as do solid calories, and whole fruit has a different macronutrient composition, including fewer calories from sugar, than does 100% fruit juice.

TREND TOWARD LESS FRUIT JUICE FOR CHILDREN

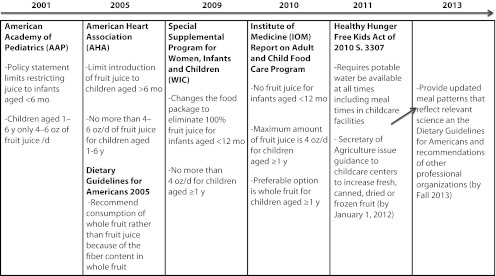

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and professional societies have recently recommended limiting children’s consumption of fruit juice to begin to address the obesity epidemic. The IOM report for the CAFCP includes recommendations for fruit juice consumption that follow those made by the American Academy of Pediatrics8 and the American Heart Association24 of no more than four to six ounces per day in children aged one to six years. The IOM report also states that the more preferable option for children older than one year is whole fruit and suggests not providing any juice to children younger than one year.25 Emphasis on the fiber in whole fruit rather than fruit juice was promoted as early as 2005 by the USDA and the US Department of Health and Human Services in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 (Figure 1).26

FIGURE 1—

A timeline of events: restriction and elimination of US children’s 100% fruit juice consumption.

We reason that consumption of juice should be delayed until children are older than the preschool years because young children should become accustomed to drinking water and milk at meals and eating whole fruit instead of any fruit juice.

The Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children food package does not support the purchase of candy or desserts, as these food items are not deemed nutritionally adequate. Similarly, the Academy of Pediatrics does not set a daily limit for consumption of candy, desserts, sodas, or even “juice treats” because these food items and beverages are not recommended for daily consumption. Although some juices do contain adequate amounts of potassium, folate, vitamin C, and vitamin A, we contend that fruit juices should be viewed similarly to other high-sugar items such as candy and desserts. Thus, the USDA’s recommendations for CAFCP should include substitution of water and whole fruit for any fruit juice servings in this vulnerable and high-risk population.

HEALTHY, HUNGER-FREE KIDS ACT OF 2010

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act presents an opportunity to affect the obesity epidemic in young, at-risk children served by the CAFCP program by eliminating 100% fruit juice from daycare centers. The CAFCP provides daily meals and snacks to 3.2 million at-risk and low-income children, including those attending Head Start. First lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move Campaign to End Childhood Obesity lists the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 as one of its main accomplishments.27 The USDA receives $10 million of support specifically to ensure implementation of the act.7 The USDA’s recommendations and guidelines for CAFCP will likely include limits on juice, in accordance with the limits on consumption of the amount of 100% juice set by the Academy of Pediatrics,8 the American Heart Association,24 and the IOM.25 However, it is imperative that the USDA take into consideration more recent relevant science (as mandated by S. 3307 of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Children Act) on risks of sugar consumption and benefits of fiber and recommend removal of all fruit juices from high-risk daycare and childcare environments.

Restrictions on fruit juice are timely, as the Let’s Move campaign hopes to reverse the course of childhood obesity in one generation. To meet such an ambitious goal, the CAFCP population, including Head Start children, should adopt healthy eating habits and gain exposure to as much whole fruit as possible. Although the IOM report recognizes that substituting fruit for fruit juice may be fiscally challenging, the IOM also notes that a variety of options are available, including dried, canned, and frozen fruit, that may help reduce overall costs.25 The USDA is mandated to take relevant science into consideration as it issues guidance and constructs meal plans, and, as noted by the Task Force on Childhood Obesity in 2011, the government will focus on childcare settings.28 Our hope and vision is that childcare settings will have high enough priority that the government will work with the USDA and the CAFCP to ensure that high-risk preschool children receive limited exposure to quickly ingested, energy-dense beverages, including fruit juice.

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases support the authors (grant DK080825 to J. M. W. and grant DK060617 M. B. H.).

We thank the University of California, San Francisco Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute KL2 Scholars program for reviewing an earlier version of this article.

References

- 1.Anderson SE, Whitaker RC. Prevalence of obesity among US preschool children in different racial and ethnic groups. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(4):344–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Risking social inequalities in US childhood obesity, 2003–2007. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(1):40–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1604–e1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dennison BA, Rockwell HL, Baker SL. Excess fruit juice consumption by preschool-aged children is associated with short stature and obesity. Pediatrics. 1997;99(1):15–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): revisions in the WIC food packages; interim rule. Federal Register. December 6, 2007;27(234): 68966–69031 7 CFR part 246 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Pub L. 111-296, S. 3307. 111th Congress (December, 13, 2010)

- 7.Food Research and Action Center Summary of Child and Adult Care Food Provisions in the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Washington, DC; 2010. Available at: www.frac.org/pdf/summary_cacfp_cnr2010.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Commission on Nutrition American Academy of Pediatrics: the use and misuse of fruit juice in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):1210–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox MK, Reidy K, Novak T, Ziegler P. Sources of energy and nutrients in the diets of infants. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(1, suppl 1):S28–S42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connor TM, Yang SJ, Nicklas TA. Beverage intake among preschool children and its effect on weight status. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):e1010–e1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butte NF, Fox MK, Briefel RRet al. Nutrient intakes of US infants, toddlers, and preschoolers meet or exceed dietary reference intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(12, suppl):S27–S37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skinner JD, Ziegler P, Pac S, Devaney B. Meal and snack patterns of infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(1 suppl 1):s65–s70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LLet al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):544–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber. Gerber NatureSelect 100% Fruit Juice—Apple. Available at: http://www.gerber.com/AllStages/products/beverages/fruit_juice_apple.aspx. Accessed October 13, 2011.

- 15.Kimm SY. The role of dietary fiber in the development and treatment of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 1995;96(5 pt 2):1010–1014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Neil CE, Zanovec M, Cho SS, Nicklas TA. Whole grain and fiber consumption are associated with lower body weight measures in US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. Nutr Res. 2010;30(12):815–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JN, Alexander KE, Ventura EE, Toledo-Corral CM, Goran MI. Inverse relation between dietary fiber intake and visceral adiposity in overweight Latino youth. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(5):1160–1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim JS, Mietus-Snyder M, Valente A, Schwartz JM, Lustig RH. The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroneterol Hepatol. 2010;7(5):251–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobrecases H, Le KA, Bortolotti Met al. Effects of short-term overfeeding with fructose, fat and fructose plus fat on plasma and hepatic lipids in healthy men. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36(3):244–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almiron-Roig E, Chen Y, Drewnowski A. Liquid calories and the failure of satiety: how good is the evidence? Obes Rev. 2003;4(4):201–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flood-Obbagy JE, Rolls BJ. The effect of fruit in different forms on energy intake and satiety at a meal. Appetite. 2009;52(2):416–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolton RP, Heaton KW, Burroughs LF. The role of dietary fiber in satiety, glucose and insulin: studies with fruit and fruit juice. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34(2):211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lustig RH. Fructose: metabolic, hedonic, and societal parallels with ethanol. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(9):1307–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LLet al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners: consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2061–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine Child and Adult Care Food Program: Aligning Dietary Guidance for All. Washington, DC; 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Department of Health and Human Services; US Department of Agriculture Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Let’s Move. Accomplishments. Available at: http://www.letsmove.gov/accomplishments. Accessed October 13, 2011.

- 28.Barnes MC. White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity: One Year Progress Report; February 2011. Available at: http://www.letsmove.gov/sites/letsmove.gov/files/Obesity_update_report.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2012 [Google Scholar]