Abstract

Objectives. Individuals released from prison have high rates of chronic conditions but minimal engagement in primary care. We compared 2 interventions designed to improve primary care engagement and reduce acute care utilization: Transitions Clinic, a primary care–based care management program with a community health worker, versus expedited primary care.

Methods. We performed a randomized controlled trial from 2007 to 2009 among 200 recently released prisoners who had a chronic medical condition or were older than 50 years. We abstracted 12-month outcomes from an electronic repository available from the safety-net health care system. Main outcomes were (1) primary care utilization (2 or more visits to the assigned primary care clinic) and (2) emergency department (ED) utilization (the proportion of participants making any ED visit).

Results. Both groups had similar rates of primary care utilization (37.7% vs 47.1%; P = .18). Transitions Clinic participants had lower rates of ED utilization (25.5% vs 39.2%; P = .04).

Conclusions. Chronically ill patients leaving prison will engage in primary care if provided early access. The addition of a primary care–based care management program tailored for returning prisoners reduces ED utilization over expedited primary care.

In the United States, 700 000 individuals are behind prison bars at any point in time; this represents the highest incarceration rate in the world.1 In the past 20 years, states’ correctional costs have risen by 315% to $44 billion annually, constituting the fastest-expanding area of government spending after Medicaid.2 Ninety-five percent of prisoners will eventually be released to the community; more than 500 000 prisoners are released annually.3 There is pressure to release more prisoners because of prison overcrowding, growing correctional health expenditures, and constrained legislative budgets.1,4,5 In October 2011, California began releasing more than 30 000 inmates from its prison system to comply with a Supreme Court ruling citing an unhealthy level of overcrowding.6 Correctional health care systems are constitutionally responsible for health care while patients are incarcerated, but not upon release.

Recently released prisoners have low educational attainment; high rates of poverty, unemployment, and homelessness; and high risk of poor health outcomes, including death, upon release.7,8 Eighty percent of released individuals have chronic medical, psychiatric, or substance abuse problems, yet only 15% to 25% report visiting a physician outside of the emergency department (ED) in the first year postrelease.8,9 Most released individuals state that they use the ED as their regular source of care.10 There is little care coordination between prison and community health systems. Few individuals are released with a sufficient supply of chronic medications, primary care follow-up, or health insurance.11,12 There is limited evidence to guide how to provide effective health care to this population after release. More primary care practices are tailoring care to high-risk populations using primary care–based, complex care management (PC-CCM) programs.13 These PC-CCM programs are designed to assist patients in managing medical problems and related psychosocial problems, in an effort to improve care and health system engagement, and to reduce costs.14–16 However, the effectiveness of these PC-CCM programs for recently released prisoners has not been demonstrated.

In 2007, we designed and compared 2 interventions to engage recently released prisoners into primary care. We offered individuals returning to San Francisco postincarceration an initial transitional care visit. After this initial visit, we randomly assigned participants to receive (1) ongoing care at Transitions Clinic (TC), a PC-CCM program for formerly incarcerated individuals consisting of primary care from a provider with experience working with this population and care management from a community health worker (CHW) with a personal history of incarceration,17 or (2) an expedited primary care (EPC) appointment at another safety-net clinic. Care management from a CHW included basic case management, as well as chronic disease self-management support, health care navigation, and patient panel management. We compared the effectiveness of TC versus EPC in increasing primary care and reducing acute care utilization. We hypothesized that individuals randomized to TC would have more primary care and fewer ED visits compared with those randomized to EPC.

METHODS

We used a community-based participatory research approach by partnering with a community advisory board consisting of individuals with a history of incarceration, representatives from community organizations working with formerly incarcerated individuals, and local policy leaders to choose the study design, protocol, and plan for analysis.18 Because low rates of primary care engagement and high rates of ED use and death among recently released prisoners are well documented,7,8 we offered transitional care to returning prisoners and compared the 2 interventions designed to improve primary care engagement.

Participants

The CHW attended a weekly mandatory parole meeting and offered all attendees a clinical transitional health care appointment within 2 weeks of their date of release. During the period of recruitment, individuals released from California state prisons were mandatorily placed on parole and required to attend this meeting.19 We recruited study participants into the trial immediately following a transitional care visit with a TC provider, which consisted of refilling medication and addressing urgent medical issues.

After the transitional clinic visit, TC providers referred patients who met enrollment criteria for further evaluation. A trained research assistant then confirmed study eligibility, explained study procedures, and obtained written consent. Eligibility criteria were (1) English speaking, (2) aged 50 years or older or having at least 1 chronic illness including mental health conditions and addiction (either self- or physician-identified), and (3) not having a primary care provider in San Francisco. We referred individuals not interested in participating or not meeting study eligibility to a primary care provider within the safety-net system.

Study Procedures

The research assistant obtained informed written consent using a teach-to-goal method, which verifies adequate understanding of study design and protocol among vulnerable populations.20 Following enrollment, the research assistant administered a 45-item questionnaire (described subsequently) and selected a consecutive, opaque, sealed envelope containing a randomly generated randomization code to assign the participant to an intervention group.21 According to randomization, the research assistant provided the participant a follow-up appointment with a reminder card with the appointment date and time at either TC or in 1 of 5 safety-net primary care clinics according to participant preference (EPC). Participants randomized to EPC did not have further contact with the TC provider or CHW.

We enrolled participants from November 15, 2007, through June 30, 2009. After completion of the baseline interview, we made no further contact with study participants. Study participants received a $10 gift card to a local grocery store as compensation. We abstracted 12-month outcomes from an electronic repository available from the safety-net health care and jail health systems. The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Committee on Human Research reviewed and approved this study, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse issued a Certificate of Confidentiality.

Interventions

The TC is a PC-CCM program embedded within a preexisting community health center. The TC’s primary care team consists of a primary care provider with experience caring for formerly incarcerated patients and a trained and certified CHW with a personal history of incarceration. The CHW had completed a 6-month certificate program at a community college and on-the-job training to learn how to navigate the local health care and social service delivery system. The CHWs provide (1) case management support, including referrals to community-based housing, education, and employment support; (2) medical and social service navigation, including accompanying patients to pharmacies, social services, and medical or behavioral health appointments; and (3) chronic disease self-management support, including home visits for health education and medication adherence support.17

Participants enrolled in the TC arm received an expedited (within 4 weeks) primary care appointment with the TC provider. All other appointments were scheduled at the discretion of the TC provider, but patients receiving care at TC could call the TC CHW to schedule urgent visits as needed. The TC program staff initially included 1 part-time provider and 1 full-time CHW but in July 2008 grew to 2 part-time providers and 2 full-time CHWs to accommodate a growing patient panel and to ensure a 1-to-30 ratio of CHW to recently released patients. The costs of this program included the CHW salary and the time costs of a TC provider supervising the CHW. Otherwise, the program utilized the existing resources in the community health center.

Participants enrolled in the EPC arm received expedited (within 4 weeks) primary care appointment with a safety-net primary care clinic provider. All other appointments were scheduled at the discretion of the new clinic provider. Providers at these safety-net clinics generally do not receive formal training in caring for individuals with a history of incarceration. The EPC did not have a CHW functioning as a care manager. Participants in TC and EPC had equal access to the resources of the local public health safety-net system.

Baseline Data

The baseline questionnaire included questions regarding marital status, education, employment, housing status, insurance status, accessible financial resources, and incarceration history. Participants reported self-rated health22 and whether a health care provider had ever diagnosed them with one of the following chronic medical problems: arthritis, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, chronic pain, depression, diabetes, heart disease or heart failure, hepatitis B or C, HIV/AIDS, hypertension, posttraumatic stress disorder, renal disease or renal failure, schizophrenia, seizure disorder, and stroke. We asked about hazardous alcohol use,23 illicit drug use, or prescription drug misuse (defined as “medications that you bought off the street or stole from someone or were given by someone other than a medical professional”). To assess past health care utilization, we asked whether participants were sent to the ED or hospitalized while incarcerated. We asked about locations where they received health care before incarceration. Given variability in the prison discharge process, we asked participants whether they had been assigned a caseworker or given discharge medications or medical records before release. Finally, we asked them about ED utilization and hospital admission in the time between their release from prison and before study enrollment.

We abstracted age, gender, race, and ethnicity on all patients from the electronic data repository maintained by the safety net system.

Outcomes

We assessed 2 primary outcome measures at 12 months after study enrollment: (1) having 2 or more visits to the study-assigned primary care clinic and (2) having any visits to the medical or psychiatric ED that did not result in a hospitalization at San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH), the only local public hospital. We also defined 4 secondary outcomes at 12 months after study enrollment: (1) rate of ED use, (2) having any hospitalization at SFGH, (3) having any incarceration in the San Francisco County Jail, and (4) time to first incarceration. Incarceration in jail includes both short stays for arrests that did not lead to conviction and longer stays, including all transfers to the state prison system. For descriptive purposes, we collected information on the primary diagnosis for each hospitalization and the number of individuals who died.

The research assistant, blinded to randomization assignment, abstracted outcomes data from the UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute’s The Health Records Electronic Data Set (THREDS) and the Jail Health Services database. The THREDS database is an electronic data repository for research that contains data from the San Francisco public health care system’s electronic health record and registration system. It includes all health care utilization data from the public health care system in San Francisco, which comprises 13 community clinics and SFGH. THREDS obtains its data on mortality from the California Department of Health Services Death Registry.24 The Jail Health Services database has information on any incarceration episode in the San Francisco County Jail, including the dates of incarceration and release.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted an intention-to-treat analysis for each of the primary and secondary outcomes and used the χ2 test to compare primary care, ED utilization, hospitalizations, and incarceration between the 2 intervention groups. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare the number of ED visits for the following categories (0, 1, 2 or 3, and 4 or more ED visits) and applied Poisson regression to compare the rates of ED utilization and hospitalization, adjusting for time incarcerated and censoring for death. We used survival analysis to compare time to first incarceration censoring participants who died. We performed frequency analyses to describe the median number of clinic visits and days incarcerated for both study arms. We considered P values of less than .05 statistically significant. We performed all statistical analyses with SAS statistical software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

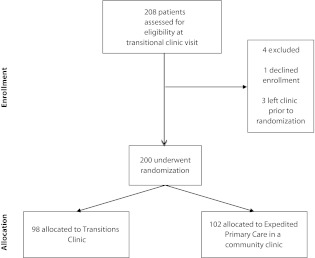

All 208 new patients who presented for an initial transitional visit were eligible for the study. Two hundred (96%) agreed to participate and were randomized. Of these, 98 were assigned to TC and 102 were assigned to EPC (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Enrollment and treatment of individuals (n = 200) released from California state prisons, 2007–2009.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Baseline characteristics between the 2 study groups were similar (Table 1). The mean age of participants was 43.2 years, 64.3% were Black and 12.2% were Hispanic, 38.3% had less than a high-school education, 6.0% were employed, 68.7% were uninsured, 95.0% had access to less than $1000, and 7.5% were stably housed. The most common self-reported diagnoses were posttraumatic stress disorder (50.5%), chronic pain (47.5%), hypertension (42.7%), depression (31.1%), hepatitis C (27.6%), and asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (23.5%). More than 90% of participants reported use of illicit drugs in their lifetime.

TABLE 1—

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants: Individuals (n = 200) Released From California State Prisons, 2007–2009

| Characteristic | Randomized to Transitions Clinic (n = 98), No. (%)a or Mean ±SD | Randomized to Expedited Primary Care in Safety Net Clinic (n = 102), No. (%)a or Mean ±SD | P |

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age, y | 42.9 ±9.7 | 43.6 ±8.3 | .56 |

| Married | 23 (23.5) | 14 (13.7) | .08 |

| Male | 89 (91.8) | 97 (96.5) | .21 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 5 (5.2) | 3 (3.0) | .65 |

| Black | 61 (63.4) | 65 (65.0) | |

| Hispanic | 10 (10.4) | 14 (14.0) | |

| Native American | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | |

| White | 20 (20.8) | 17 (17.0) | |

| Educational attainment | |||

| < high school | 33 (33.7) | 43 (43.0) | .4 |

| High school | 39 (39.8) | 35 (35) | |

| > high school | 26 (26.5) | 22 (22.0) | |

| Employed | 8 (8.2) | 4 (3.9) | .2 |

| Living in San Francisco before incarceration | 68 (75.6) | 78 (83.9) | .16 |

| Insured | 32 (33.3) | 30 (29.4) | .55 |

| Insurance provider | |||

| Medicaid | 13 (43.3) | 11 (39.3) | .75 |

| Medicare | 4 (13.3) | 4 (14.3) | .92 |

| Employer | 8 (26.7) | 9 (32.1) | .65 |

| Healthy San Franciscob | 4 (13.3) | 3 (10.7) | .76 |

| Money accessible now, $ | 2728 ±25 256c | 392 ±2217 | .36 |

| Current housing status | |||

| Homeless | 12 (12.2) | 16 (15.6) | .63 |

| Living with family or friends | 35 (35.7) | 29 (28.4) | |

| Transitional housingd | 45 (45.9) | 48 (47.1) | |

| Stable housing | 6 (6.1) | 9 (8.8) | |

| Incarceration history | |||

| Mean age at first incarceration | 20.1 ±10.4 | 20.1 ±7.8 | .98 |

| Mean number of times incarcerated | 6.4 ±11.6 | 6.7 ±8.4 | .88 |

| Mean time incarcerated, mo | 32.9 ±60.0 | 39.8 ±57.9 | .43 |

| Total length of incarceration, y | |||

| < 5 | 19 (19.8) | 22 (21.6) | .39 |

| 5– < 10 | 26 (27.1) | 18 (17.6) | |

| 10–15 | 15 (15.6) | 22 (21.5) | |

| > 15 | 36 (37.5) | 40 (39.2) | |

| Currently on parole | 88 (90.7) | 95 (94.1) | .37 |

| Physical health history | |||

| Self-rated health: fair or poor | 32 (33.0) | 43 (42.6) | .16 |

| Chronic disease | |||

| Arthritis | 22 (22.4) | 17 (16.7) | .3 |

| Asthma or COPD | 26 (26.8) | 21 (20.6) | .3 |

| Cancer | 0 (0) | 2 (2.0) | .16 |

| Chronic pain | 46 (46.9) | 49 (48.0) | .88 |

| Diabetes | 13 (13.4) | 17 (16.7) | .52 |

| Heart disease or heart failure | 9 (9.3) | 12 (11.8) | .57 |

| Hepatitis B | 6 (6.2) | 6 (5.9) | .93 |

| Hepatitis C | 23 (23.7) | 32 (31.4) | .23 |

| HIV/AIDS | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | .97 |

| Hypertension | 33 (34.0) | 52 (51.0) | .02 |

| Renal disease or renal failure | 3 (3.1) | 3 (2.9) | .95 |

| Seizure disorder | 8 (8.3) | 6 (5.9) | .51 |

| Stroke | 4 (4.1) | 2 (2.0) | .37 |

| Chronic disease diagnosis in prison | 32 (33.3) | 47 (48.0) | .04 |

| Comorbidities,e no. | |||

| 0 | 16 (16.3) | 19 (18.6) | .26 |

| 1 | 32 (32.6) | 22 (21.6) | |

| 2 | 25 (25.5) | 21 (20.6) | |

| 3 | 10 (10.2) | 16 (15.7) | |

| 4 | 8 (8.1) | 16 (15.7) | |

| ≥ 5 | 7 (7.1) | 8 (7.8) | |

| Mental health history | |||

| Depression | 29 (29.9) | 33 (32.5) | .71 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 46 (47.4) | 54 (53.5) | .4 |

| Schizophrenia | 5 (5.1) | 8 (7.8) | .44 |

| Mental health treatment (ever) | 38 (38.7) | 44 (43.4) | .53 |

| Mental health hospitalization (ever) | 18 (18.4) | 26 (25.4) | .22 |

| Suicide attempts (ever) | 16 (16.3) | 20 (19.8) | .52 |

| Substance abuse history | |||

| Current hazardous alcohol usef | 7 (7.1) | 12 (11.8) | .26 |

| Current illicit drug use | 7 (8.0) | 12 (12.5) | .33 |

| Ever prescription drug misuse | 46 (48.4) | 44 (44.0) | .53 |

| Ever used illicit drugs | 88 (91.7) | 96 (95.0) | .34 |

| Ever injected drugs | 33 (38.0) | 44 (45.4) | .31 |

| Ever overdosed on drugs | 18 (20.7) | 19 (19.8) | .88 |

| Ever enrolled in drug treatment program | 69 (74.2) | 68 (68.7) | .4 |

| Health care utilization | |||

| Health care utilization while in prison | |||

| ED visit | 34 (35.4) | 33 (32.4) | .65 |

| Hospital admission | 25 (26.0) | 24 (23.5) | .68 |

| In community before incarceration: Where did you receive regular health care?g | |||

| Primary care clinic | 26 (26.8) | 35 (34.6) | .23 |

| Emergency department | 67 (69.1) | 65 (64.4) | .48 |

| Urgent care clinic | 30 (31.0) | 38 (37.6) | .32 |

| No health care anywhere | 6 (6.3) | 6 (5.9) | .91 |

| Transitional health care | |||

| Have case manager | 44 (45.8) | 55 (54.5) | .23 |

| Released from prison with medical records | 13 (13.4) | 17 (16.8) | .5 |

| Currently on at least 1 daily prescription medication | 68 (70.1) | 71 (70.3) | .98 |

| Released from prison with medicationh | 43 (63.3) | 52 (73.2) | .2 |

| After prison release (before study enrollment) | |||

| ED visit | 14 (14.4) | 14 (13.9) | .91 |

| Hospital admission | 4 (4.1) | 5 (5.0) | .78 |

Note. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED = emergency department.

Categories may not add to total number because of missing data, which was < 10% of total responses for all data presented.

A San Francisco program started in 2006 that made health care services accessible and affordable by creating primary care medical homes for uninsured residents.

This reflects the response of a single outlier who reported $250 000 in money available now. If the outlier is removed from the analysis the mean money available among Transitions Clinic participants was $179 ±$1031.1. There is no difference in the mean money available between Transitions Clinic and expedited primary care participants with the outlier excluded.

Comorbidities included any physical health conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, hepatitis C), mental health conditions (e.g., depression, posttraumatic stress disorder), and substance abuse or dependence.

Individuals released from prison sometimes live in community sober houses and residential drug treatment programs as a condition of their parole.

More than 2 positive responses on CAGE questionnaire is suggestive of alcohol disorder.

Responses were not mutually exclusive. Individuals could choose both primary care clinic and emergency department.

Denominator is among individuals who are currently on at least 1 daily prescription (n = 68 for Transitions Clinic and n = 71 for expedited primary care).

Almost a third (30.8%) reported that they obtained health care in a primary care clinic before their most recent incarceration, and 66.7% reported using the ED or urgent care for health care.

Among the 139 participants who reported taking a daily medication while incarcerated, 31.6% were released with no medications. Less than one fifth of participants (15.2%) were released with their medical records.

Before study enrollment, 14.0% of participants reported receiving care in the ED, and 4.5% reported hospitalization in the 2 weeks after prison release.

Health Care Utilization

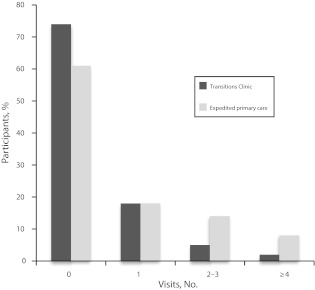

After 12 months of follow-up, 37.7% of TC and 47.1% of EPC participants (P = .18) made 2 or more visits to their assigned primary clinic according to safety net registry data (Table 2). The median number of primary care appointments was the same for TC and EPC participants (1 visit; interquartile range [IQR] = 0–5). The TC participants were less likely to make any visits to the ED compared with those randomized to EPC (25.5% vs 39.2%; P = .04). They were also less likely to make 4 or more visits to the ED (2.0% vs 7.8%; Figure 2). When we adjusted for time incarcerated and deaths, TC participants had a 51% lower annual rate of ED visits, with an incidence rate ratio of 0.49 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.34, 0.70).

TABLE 2—

Study Outcomes: Primary Care Utilization, Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Incarceration by Study Group: Individuals (n = 200) Released From California State Prisons, 2007 to 2009

| Outcome | Randomized to Transitions Clinic (n = 98), No. (%) | Randomized to Expedited Primary Care (n = 102), No. (%) | P |

| Primary care utilization: ≥ 2 visits to assigned clinic | 37 (37.7) | 48 (47.1) | .18 |

| Any emergency department use at SFGH | 25 (25.5) | 40 (39.2) | .04 |

| Any hospitalization at SFGH | 10 (10.2) | 15 (14.7) | .34 |

| Any incarceration in San Francisco County Jail | 57 (58.1) | 54 (52.9) | .46 |

Note. SFGH = San Francisco General Hospital.

FIGURE 2—

Participant visits to emergency department in year following enrollment among individuals (n = 200) released from California state prisons, 2007–2009.

Note. Wilcoxon rank sum test P = .015.

There were no differences in hospitalizations (10.2% vs 14.7%; P = .34) between the 2 intervention groups; the hospitalization incidence rate ratio was 0.89 (95% CI = 0.44, 1.82). A review of primary admitting diagnoses in the 26 hospitalizations demonstrated that 34.6% of hospitalizations were for infectious etiologies, 19.2% were for musculoskeletal injuries, 15.4% were for nonemergent surgeries, 15.4% were for complications of diabetes, 11.5% were for gastrointestinal diseases, and 3.8% were for psychiatric diagnoses. Two participants died in the group randomized to TC; none died in the EPC group.

Return to Jail

We found no difference in rates of return to jail between the groups (58.1% vs 52.9%; P = .46) nor in time to first incarceration among those who returned to jail (120.3 vs 138.3 days; P = .31) in our time-to-event analysis. The median (IQR) days of incarceration for TC participants compared with EPC participants was 6 (0–18) versus 1 (0–18; P = .11).

DISCUSSION

In a population of recently released prisoners with high rates of chronic medical, psychiatric, and substance abuse problems and low rates of previous primary care engagement, we observed no difference in engagement in primary care between the 2 intervention arms. Both interventions engage individuals into primary care through outreach immediately after prison release and early transitional care followed by an expedited primary care appointment. More than 60% of study participants were seen in a primary care clinic at least once in the 12-month follow-up period of our study, and 42% were seen 2 or more times, suggesting that individuals released from prison will use and remain in primary care if efforts are made to provide access to care immediately upon release.

We found a 15% absolute reduction in the proportion of participants with any ED visits and a 51% reduction in the rate of ED visits among those participants who received ongoing primary care in TC compared with EPC. Given the current interest in care management for high-risk, high-utilizing populations in primary care,14,15,25–28 this PC-CCM intervention may be an effective model for reducing ED utilization in recently released prisoners. These data suggest that a small number of patients may account for a large part of the difference in acute care utilization and that the PC-CCM intervention was effective at reducing both any ED use and frequent utilization. In contrast to standard care management programs, which employ individuals with nursing or social work degrees,28–30 our study used a CHW with a past history of incarceration, who had completed a 6-month certificate program at a community college. Also, this intervention employed primary care providers with past experience working with recently released prisoners; it is possible that providing training in residency or continuing medical education courses could sufficiently train primary care providers to care for former prisoners. Future studies should examine the ability to replicate these findings in other community health centers caring for formerly incarcerated patients.

Although participants had an initial transitional visit within 2 weeks of prison release, 28 participants (14.0%) reported an ED visit and 9 individuals (4.5%) reported being hospitalized between prison release and the transitional visit that occurred before study enrollment. These visits were self-reported, occurred before enrollment in the study, and could not be confirmed by registry data. This suggests that future interventions should bridge health care from prison to the community earlier and that CHWs should engage individuals with chronic conditions before prison release. Alternatively, health care teams that work in both the community and the correctional facility could provide continuity of care for prisoners, such as the successful program in the Hampden County jail in Massachusetts, although this may be limited by proximity of communities and correctional facilities.30,31

Our interventions showed no statistically significant difference in hospitalization rates. Because no study in the United States has systematically investigated rates of hospitalization postrelease, there was no basis for comparison. We may have had insufficient power to evaluate hospitalization rates. However, our data illustrated that many hospitalizations were attributable to acute injuries from unintentional injuries or assaults. These may be important targets for future interventions and point to the need for community-based violence reduction strategies.30,32,33 We also found significant rates of return to jail in both groups with no demonstrable difference between the 2 intervention groups. Released prisoners residing in San Francisco have one of the highest rates of recidivism in the country (78.3% of released inmates return to prison within 3 years of release).34 Changes in incarceration rates in San Francisco may be less amenable to primary care–based interventions as other studies have suggested.35,36

This randomized trial is the first to demonstrate that older adults and those with chronic conditions leaving prison can be engaged into primary care and that a tailored PC-CCM program can reduce both any ED utilization and frequent ED utilization. This study capitalized on a high participation rate and broad inclusion criteria, a 12-month follow-up, blinded collection of outcome data, and complete data for 100% of the sample from the city’s only public safety-net health care system. Despite this, we could not assess the types and costs of services provided. It was unclear whether ED visits were for prescription refills, injuries, or for treatment of life-threatening conditions. We were unable to obtain utilization data from health care providers outside the San Francisco safety-net system, including private EDs or reincarceration data from jail systems outside San Francisco County Jail, in communities where participants may abscond. However, SFGH is the only public ED in the city, and previous studies in California have demonstrated that the majority of ambulatory health care utilization of recently released prisoners occurs in the public health system.37 Under randomization, these limitations would have affected both groups equally.

Because participants were recruited after a transitional health care visit, we may have selected participants who were already predisposed to primary care utilization, thereby limiting generalizability of our results. In addition, comparison of TC to EPC does not represent current care within most safety-net systems, where CHWs do not attend a weekly parole meeting, and transitional visits and expedited primary care follow-up visits are not provided. The study design may bias our results toward the null hypothesis, and we might expect greater reductions in ED utilization if we had compared TC to the current standard of primary care for recently released prisoners. Finally, we do not know whether our findings are generalizable to other locations, including rural settings where there is not a robust safety-net system. However, we designed and evaluated 2 interventions that we believe are replicable in any community health center.

As the number of individuals released from prison continues to grow for the foreseeable future,4 local communities must confront the rising costs of caring for this population in times of limited resources. National health reform brings the promise of coverage for many of these high-risk, recently released prisoners through Medicaid expansion,38 increased investment in patient-centered medical homes, and increased reimbursement for care management programs.15,39,40 However, if Massachusetts is a harbinger for health reform on a national scale, improved coverage may lead to increased ED volume in safety-net systems.41 This study provides data on how local safety-net health care systems might capitalize on recent health policy changes by designing PC-CCM programs to engage returning prisoners into primary care and reduce acute care utilization. Modest amounts of funding from either federal or state governments to local safety-net health care systems to hire and supervise a CHW could expand health care access and enhance primary care for formerly incarcerated individuals, complementing ongoing government efforts to improve health care for these individuals while they are incarcerated.

Acknowledgments

The San Francisco Foundation, the California Endowment, California Wellness Foundation, California Policy Research Center, and the San Francisco Department of Public Health funded the interventions and evaluation. E. A. Wang receives salary support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (award 5K23HL103720).

We would like to thank study participants, Southeast Health Center staff, and the community advisory board for the success of this study.

Note. The sponsors had no role in the design of the study, analysis of data, or the preparation, review, or approval of the article.

Human Participant Protection

The University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research reviewed and approved this study, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse issued a Certificate of Confidentiality.

References

- 1.One in 100: Behind Bars in America 2008. Washington DC: The Pew Center on the States; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.One in 31: The Long Reach of American Corrections. Washington, DC: The Pew Center on the States; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e7558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archibald RC. California, in financial crisis, opens prison doors. New York Times; March 24, 2010; A14 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, McCallum VA, Perez SD, Brzozowski AK, Steenland NK. Prisoner survival inside and outside of the institution: implications for health-care planning. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(5):479–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medina J. California Begins Moving Prison Inmates. New York Times; October 8, 2011. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/09/us/california-begins-moving-prisoners.html. Accessed February 10, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RAet al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallik-Kane K, Visher CA. Health and Prisoner Reentry: How Physical, Mental, and Substance Abuse Conditions Shape the Process of Reintegration. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallik-Kane K. Returning Home Illinois Policy Brief: Health and Prisoner Reentry. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Justice Policy Center; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conklin TJ, Lincoln T, Tuthill RW. Self-reported health and prior health behaviors of newly admitted correctional inmates. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1939–1941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakeman SE, McKinney ME, Rich JD. Filling the gap: the importance of Medicaid continuity for former inmates. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):860–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flanagan NA. Transitional health care for offenders being released from United States prisons. Can J Nurs Res. 2004;36(2):38–58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millet R. Care Management of Patients With Complex Health Care Needs. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/pr/product.jsp?id=52372. Accessed June 15, 2012.

- 14.Steiner BD, Denham AC, Ashkin E, Newton WP, Wroth T, Dobson LA., Jr Community care of North Carolina: improving care through community health networks. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):361–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bielaszka-DuVernay C. Vermont’s blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(3):383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qualis Health The Safety Net Medical Home Initiative: transforming safety net clinics into patient-centered medical homes. 2011. Available at: http://www.qhmedicalhome.org/safety-net/about.cfm. Accessed February 10, 2012

- 17.Wang EA, Hong CH, Samuels L, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kushel M. Transitions clinic: creating a community-based model of healthcare for recently released California prisoners. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(2):171–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RRet al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Non-Revocable Parole. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Division of Adult Parole; 2010. Available at: http://www.cdcr.ca.gov/parole/Non_Revocable_Parole/index.html. Accessed June 15, 2012.

- 20.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Williams BA, Barnes DE, Lindquist K, Schillinger D. Use of a modified informed consent process among vulnerable patients: a descriptive study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):867–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet. 2002;359(9306):614–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE., Jr The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26(7):724–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liskow B, Campbell J, Nickel EJ, Powell BJ. Validity of the CAGE questionnaire in screening for alcohol dependence in a walk-in (triage) clinic. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56(3):277–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.University of California San Francisco, Clinical and Translational Science THREDS: The Health Record Data Service. Available at: http://ctsi.ucsf.edu/research/threds. Accessed February 10, 2012

- 25.Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(17):1771–1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horwitz LI, Bradley EH. Percentage of US emergency department patients seen within the recommended triage time: 1997 to 2006. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(20):1857–1865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boult C, Reider L, Leff Bet al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):460–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorr DA, Wilcox AB, Brunker CP, Burdon RE, Donnelly SM. The effect of technology-supported, multidisease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2195–2202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wohl DA, Scheyett A, Golin CEet al. Intensive case management before and after prison release is no more effective than comprehensive pre-release discharge planning in linking HIV-infected prisoners to care: a randomized trial. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):356–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rich JD, Holmes L, Salas Cet al. Successful linkage of medical care and community services for HIV-positive offenders being released from prison. J Urban Health. 2001;78(2):279–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts C, Kennedy S, Hammett T, Rosenberg N. Discharge Planning and Continuity of Care for HIV-Infected State Prison Inmates as They Return to the Community: A Study of Ten States. Report commissioned by the National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001.

- 32.Gilligan J, Lee B. The Resolve to Stop the Violence Project: reducing violence in the community through a jail-based initiative. J Public Health (Oxf). 2005;27(2):143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety. JAMA. 2009;301(2):183–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chapman SF, Grealish B, Grassel K, Viscuso B, Lam L. Adult Institutes Outcome Evaluation Report. Commissioned by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation; 2010.

- 35.Sheu M, Hogan J, Allsworth Jet al. Continuity of medical care and risk of incarceration in HIV-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2002;11(8):743–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, Perkins T, Richie BE. Coming home from jail: the social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1725–1736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis LM, Williams MV, Pitkin-Derose KPSet al. Understanding the Public Health Implication of Prisoner Reentry in California: State of the State Report. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varney S. California Medicaid expansion: a lifeline for ex-convicts [transcript]. National Public Radio. September 13, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holahan J, Headen I. Medicaid Coverage and Spending in Health Reform: National and State-by-State Results for Adults at or Below 133% FPL. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Redhead CS, Williams ED. Public Health, Workforce, Quality, and Related Provisions in Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Summary and Timeline. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lasser KE, Kronman AC, Cabral H, Samet JH. Emergency department use by primary care patients at a safety-net hospital. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):278–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]