Abstract

Purpose

This study sought to characterize temperament traits in a sample of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), ages 3–7 years old, and to determine the potential association between temperament and sensory features in ASD. Individual differences in sensory processing may form the basis for aspects of temperament and personality, and aberrations in sensory processing may inform why some temperamental traits are characteristic of specific clinical populations.

Methods

Nine dimensions of temperament from the Behavioral Style Questionnaire (McDevitt & Carey, 1996) were compared among groups of children with ASD (n = 54), developmentally delayed (DD; n = 33), and the original normative sample of typically developing children (Carey & McDevitt, 1978; n = 350) using an ANOVA to determine the extent to which groups differed in their temperament profiles. The hypothesized overlap between three dimensional constructs of sensory features (hyperresponsiveness, hyporesponsivness, and seeking) and the nine dimensions of temperament was analyzed in children with ASD using regression analyses.

Results

The ASD group displayed temperament scores distinct from norms for typically developing children on most dimensions of temperament (activity, rhythmicity, adaptability, approach, distractibility, intensity, persistence, and threshold) but differed from the DD group on only two dimensions (approach and distractibility). Analyses of associations between sensory constructs and temperament dimensions found that sensory hyporesponsiveness was associated with slowness to adapt, low reactivity, and low distractibility; a combination of increased sensory features (across all three patterns) was associated with increased withdrawal and more negative mood.

Conclusions

Although most dimensions of temperament distinguished children with ASD as a group, not all dimensions appear equally associated with sensory response patterns. Shared mechanisms underlying sensory responsiveness, temperament, and social withdrawal may be fruitful to explore in future studies.

Keywords: autism, developmental delay, temperament, sensory processing and reactivity

Introduction

Research suggests that individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) present with unique profiles of both temperament (Hepburn & Stone, 2006) and sensory responsiveness (Baranek et al., 2006; Dawson & Watling, 2000; Kientz & Dunn, 1997) that may be maladaptive with respect to broader developmental and behavioral outcomes (Eaves, Ho, & Eaves, 1994; Hilton et al, 2010; Watson et al., 2011). However, it is not known to what extent constructs of temperament and sensory responsiveness overlap conceptually and how such overlap may implicate common neural pathways that underlie some core features of ASD to test in future research. Individual differences in sensory processing may form the basis for aspects of temperament and personality (Dunn 1997; 2001), and aberrations in sensory processing may inform why some temperamental traits are characteristic of specific clinical populations.

ASD is a pervasive developmental disorder that is diagnosed behaviorally based on deficits in three core areas (social interaction, communication, and restricted, repetitive behaviors) (APA, 2000). Behaviorally based ASD diagnostic criteria are conceptually linked to models of temperament. Thomas and Chess (1963), pioneers in temperament research, developed a framework that defines temperament as a child’s individual ‘behavioral style’ (Chess & Thomas, 1996; Thomas, Chess, & Birch, 1968; Thomas, Chess, Birch, Hertzig, & Korn, 1963). According to Thomas and Chess, temperament refers to the “how rather than the what (ability and content) or the why (motivations) of behavior” (Chess & Thomas, 1996, p 32). In this definition, “temperament is a phenomenological term and has no implications as to etiology or immutability” (Chess & Thomas, 1996, p 33). Thomas and Chess propose nine dimensions (Thomas, Chess, & Birch, 1968) of temperament that are summarized in Table 1. These dimensions serve as a blueprint for commonly used temperament measures such as the Behavioral Style Questionnaire (BSQ; McDevitt & Carey, 1996), Child Temperament Questionnaire (CTQ; Thomas & Chess, 1977), and Temperament Assessment Battery for Children (TABC; Martin, 1988). Just like instruments used to diagnose ASD, these measures of temperament gather information about how a child behaves by directly observing a child’s behavior or by asking someone who has observed their behavior. While ASD diagnostic tools seek to characterize behavior related to three specific core deficits, measures of temperament seek to more broadly capture a child’s behavioral style. In effect, the behaviors that a child displays that result in him/her meeting ASD criteria represent a subset of the behaviors that may also comprise his/her temperament (as defined by Thomas, Chess, & Birch, 1968).

Table 1.

Descriptions of the Nine Dimensions of Temperament and BSQ Subscale Scoring

| Dimension | Descriptiona | Lower BSQ Scores Indicateb |

Higher BSQ Scores Indicateb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | The level, tempo, and frequency with which a motor component is present in a child’s functioning. | more inactive | more active |

| Rhythmicity | The degree of regularity of repetitive biological functions. | more rhythmic | more arrhythmic |

| Distractibility | The effectiveness of extraneous environmental stimuli in interfering with, or in altering the direction of, the ongoing behavior. | less distractible | more distractible |

| Approach | The child’s initial reaction to any new stimulus, be it food, people, places, toys, or procedures. | more approaching | more withdrawn |

| Adaptability | The ease or difficulty which the initial pattern of response can be modified in the direction desired by the parents or others. | quicker to adapt | slower to adapt |

| Persistence | The child’s maintaining an activity in the face of obstacles to its continuation. | more persistent | less persistent |

| Threshold | The level of extrinsic stimulation that is necessary to evoke a discernable response. | more nonreactive | more sensitive |

| Intensity | The energy content of the response, irrespective of whether it is positive or negative. | milder intensity | increased intensity |

| Mood | The amount of pleasant, joyful, friendly behavior as contrasted with unpleasant, crying, unfriendly behavior. | more positive | more negative |

Note: BSQ = Behavioral Style Questionnaire;

Descriptions are quoted from Thomas, Chess, & Birch, 1968, p. 19–24;

Given this inherent conceptual overlap, it is not surprising that previous studies have found that the temperament profiles for children with ASD, as a group, differ from that of typically developing (TD) children (Bailey et al., 2000; Bieberich & Morgan, 2004; Garon et al., 2009; Hatton et al., 1999; Hepburn & Stone, 2006). Compared to TD comparison groups, children with ASD were more active, more withdrawn (Bailey et al., 2000; Bieberich & Morgan, 2004; Garon et al., 2009), less adaptive (Bailey et al., 2000; Hepburn & Stone, 2006), less persistent (Bailey et al., 2000), less intense in their reactions (Hatton et al., 1999), less sensitive to environmental stimuli (Hepburn & Stone, 2006), and had lower positive affect, higher negative affect, and more difficulty controlling attention and behavior (Garon et al., 2009). Only a few published studies have compared the temperament of ASD and developmentally delayed (DD) groups, finding that children with ASD showed less self-regulation (Bieberich & Morgan, 2004; Gomez & Baird, 2005); however, these studies used a different model of temperament (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981) than the Thomas & Chess (1968) model adopted for the present study.

The presence of unusual sensory features in ASD dates back to Kanner’s (1943) early descriptions of sensory differences (e.g., visual fascinations; auditory sensitivities). Atypical sensory features are thought to result from aberrant sensory processing, and may be evident across all sensory modalities. Research has continued to identify unusual sensory features in children with autism that are noted to be highly prevalent (Baranek et al., 2006; Dawson & Watling, 2000; Tomcheck & Dunn, 2007), but vary depending upon the format of measures used such as direct observation, caregiver report, firsthand accounts, and/or retrospective video analysis (Schoen, Miller & Green, 2008), age of the children in the studies, as well as level of specificity of items/patterns tapped. While research continues to examine whether sensory features are universal in children with ASD, evidence suggests that unique patterns of sensory response differentiate children with ASD from both TD (Kientz & Dunn, 1997; Talay, Ongan, & Wood, 2000; Tomcheck & Dunn, 2007) and DD comparison groups (Baranek et al., 2006; Rogers, Hepburn, & Wehner, 2003). Although group differences exist between persons with ASD and other comparison groups, there is also considerable heterogeneity in symptom expression within this population (Ben-Sasson et al., 2008; Lane, Young, Baker & Angley, 2010; Watling et al., 2001).

Some researchers suggest that individual differences in sensory processing may result in specific behavioral manifestations of sensory features, but also may form the basis for aspects of temperament and personality (Dunn 1997; 2001). Thus, aberrations in sensory processing may inform why some temperamental traits are characteristic of specific clinical populations. Although no published studies have empirically tested associations between sensory features and temperament, there appears to be much conceptual overlap between these domains, as typically reflected in parent-report or observational measures (Boyd et al., 2010; Liss, Sauliner, Fein, & Kinsbourne, 2006; Tomchek & Dunn, 2007). Furthermore, when Thomas and Chess (1996) conceptualized their nine dimensions of temperament, they identified threshold of responsiveness as the level of extrinsic stimulation that is necessary to evoke a discernable response (Fox & Polak, 2004; Thomas, Chess, & Birch, 1968). Thomas and Chess theorized that individuals either have a high threshold of response (requiring a high level of sensory stimulation to evoke a response) or a low threshold of response (requiring a low level of sensory stimulation to evoke a response). According to their model, an individual’s behavior could be categorized somewhere along a continuum between these two extremes.

In contrast to the assumption that an individual’s threshold of sensory responsiveness can be placed along a single continuum, recent research suggests that sensory responsiveness may be a multidimensional phenomenon in children with ASD. Sensory features are commonly described as falling into three distinct but overlapping dimensional constructs, including hyperresponsiveness, hyporesponsiveness, and sensory seeking (Baranek, 2002; Ben-Sasson et al., 2008; Liss et al., 2006). Hyperresponsiveness refers to a display of exaggerated responses, resulting in avoidance or aversion to specific sensory stimuli that are not generally considered to be overwhelming or threatening by TD individuals (e.g., covering ears to indicate sound aversion) (Baranek, David, Poe, Stone, & Watson, 2006; Schoen, Miller, & Green 2008). Hyporesponsiveness may consist of a lack of behavioral response or a muted response to sensory stimuli (e.g., ignores name call, high tolerance for pain) (Baranek et al., 2006). Sensory seeking behaviors occur when a child engages in activities that appear to provide intense sensory input, as indicated by an unwavering interest and persistent engagement in a particular stimulus (Dunn, 1997; Liss et al., 2006). Thus, theoretically, varying levels of these three sensory constructs may coexist in the same child, and may explain some of the heterogeneity in this population.

The simultaneous manifestation of hypothetically opposite sensory response patterns (hyper- and hyporesponsivness) in ASD connotes an interesting paradox that cannot be easily assimilated into Thomas and Chess’s unidimensional conceptualization of “threshold of responsiveness.” Behavioral descriptions of individuals with ASD underscore the high prevalence of both hypo- and hyperresponsiveness in the same individuals (Baranek et al., 2006; Ben-Sasson, Cermak, Orsmond, Tager-Flusberg, Carter, Kadlec, & Dunn, 2007; Tomchek & Dunn, 2007). Measuring sensory responsiveness along a single dimension may also limit researchers’ approach to understanding the pathogenesis or functional impact of concomitant sensory response patterns in ASD.

One popular model of sensory processing (Dunn 1997; 2001) describes a continuum of sensory responsiveness (low to high) interacting with a second continuum of self-regulation strategies (active to passive). These interacting dimensions result in a categorical taxonomy of four sensory processing quadrants, each representing a particular typology. One advantage of this model is that it affords two additional response patterns beyond hypo- and hyperresponsiveness. For example, the sensory seeking pattern is viewed as an active accommodation to modulate a high threshold for stimulation and increase sensory registration (e.g., counteract hyporesponsiveness), whereas avoidance is an accommodation to excessive sensory sensitivity (e.g., counteract hyperresponsiveness). The four quadrant model has advantages for clinical interpretation and allows for tagging of instructional strategies to specific sensory patterns. However, it is more difficult to reconcile the co-existence of theoretically very opposing patterns, such as extreme levels of both hypo- and hyperresponsiveness. Intercorrelations of hyper- and hyporesponsiveness (with or without seeking patterns) are reported in empirical studies and alternate conceptual models have been proposed (Ben-Sasson et al., 2008; Boyd et al., 2010; Liss et al., 2006; Reynolds & Lane, 2008). Furthermore, recent studies show that the three sensory constructs of interest in this study may explain some of the heterogeneity in ASD as well as differential associations with core features and adaptive behavior (Ben-Sasson et al., 2008; Lane et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2011).

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The present study has two aims. First, we aimed to determine the replicability of previous studies that found differences between children with ASD and TD on measures of temperament, and expand these findings by specifically testing differences between children with ASD and children with DD. Based on previous characterizations of temperament in children with ASD using the Thomas and Chess model of temperament (Bailey, et al., 2000; Bieberich & Morgan, 2004; Garon et al., 2009; Hatton, et al., 1999; Hepburn & Stone, 2006), we hypothesized that compared to the TD group, the ASD group would be temperamentally more active, more withdrawn, less adaptive, less intense in their reactions, and less sensitive to environmental stimuli. We expected that because social impairment is a diagnostic feature of autism, and because high levels of both sensory hypo- and hyperresponsiveness may contribute to difficulties with social engagement (Baranek et al., 2006), the ASD group will be more temperamentally withdrawn (on the approach dimension) than the DD group. Once we established how the temperament of children with autism differed from TD and DD groups, we sought to explore how sensory responsiveness might explain the unique temperament of children with ASD.

Our second aim was to test associations between three constructs of sensory responsiveness and nine dimensions of temperament for children with ASD. We offered two hypotheses building from the notion that sensory responsiveness is a central component of temperament. First, because the temperament dimension of threshold of responsiveness is conceptualized as a continuum or low to high reactivity, we hypothesized that low scores on the threshold of responsiveness dimension would be associated with measures of sensory hyporesponsiveness, and that high scores on the threshold of responsiveness dimension would be associated with measures of sensory hyperresponsiveness. Thus, separating patterns of sensory response would help to detect differences that combined measures of sensory features would obscure. Second, due to their shared reliance on intact sensory processing mechanisms, we hypothesized that all three sensory patterns would be associated to some degree with several other dimensions of temperament but that these associations would vary across sensory patterns as follows: (a) sensory hyporesponsiveness would be associated with increased withdrawal (on the approach dimension), lower distractibility, milder intensity, lower persistence and slowness to adapt; (b) Sensory hyperresponsiveness would be associated with higher activity, decreased rhythmicity, increased withdrawal (on the approach dimension), higher distractibility, higher intensity, more negative mood, and slowness to adapt; and (c) sensory seeking behavior was hypothesized to be associated with higher activity, higher persistence, and increased approach.

Methods

Participants

The participants were 87 children (76 = male), ages 36–84 months (M = 55.17 months; SD = 13.67 months). Seventy of the children were Caucasian, 9 were African-American, and 8 were of multiple racial/ethnic origins. Level of maternal education was heterogeneous, as some mothers had not completed high school while other mothers had completed postgraduate degrees. Diagnostic groups included children with ASD (n = 54) and children with other developmental delays (n = 33).

Participants in the ASD group (n = 54) had a documented clinical diagnosis of an ASD from a professional, met criteria for ASD on the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord, Rutter &, Le Couteur, 1994) and/or the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000), and met criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis of Autistic Disorder based on expert clinical impression. Exclusion criteria included known genetic conditions (e.g. tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, fragile X, Rett’s syndrome) and seizure disorders or epilepsy as confirmed by medical records and/or previous medical examination; hearing and visual acuity that cannot be corrected to within normal limits; significant dysmorphic features evident and discovered during screening questions or documented in medical records; and lack of ambulation or significant physical impairments (e.g., cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy). Chronological age ranged from 36 to 84 months (M = 56.17; SD = 13.67) and mental age ranged from 4 to 72 months (M = 36.11; SD = 19.88). The majority (83.3%) of participants with ASD were male.

The developmentally delayed (DD) group (n = 33) included children with diagnosed developmental disabilities associated with intellectual impairment (e.g., Down syndrome, mental retardation, etc.) or other diagnoses (e.g., speech language disorder, etc.) and documentation of significant developmental delays (> −1.5 SDs) in at least two areas of development on standardized assessments. Exclusion criteria for the DD group included displaying significant symptoms of autism on the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Schopler, Reichler, DeVellis, & Daly, 1988), Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT; Robins et al., 2001), or ADOS (Lord et al., 2000); having an older sibling diagnosed with ASD; having a confirmed seizure disorder; having hearing or visual acuity that cannot be corrected within normal limits; significant physical impairments; or being too developmentally immature (MA less than 6 months) to manipulate items in sensory tests. Chronological age ranged from 36 to 83 months (M = 54.70; SD = 12.99) and mental age ranged from 15 to 69 months (M = 43.48; SD = 13.60). The majority (72.7%) of participants with DD were male. Participants in the ASD and DD groups did not significantly differ on chronological age (t(86) = .54; p = .62), mental age (t(86) = .94; p = .07), or gender (χ2(1) = 1.40; p = .24)

Norms from a reference group of typically developing children were used from the original psychometric study of the BSQ (Carey & McDevitt, 1978). This reference group included 350 typically developing children between 3 and 7 years of age.

Measures

Child temperament. The Behavioral Style Questionnaire (BSQ; McDevitt & Carey, 1996) is a 100-item questionnaire completed by parents. Each question is answered on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 6 (almost always).

The BSQ is based on the nine dimensions of temperament (Table 1) developed from the New York Longitudinal Study (Thomas, Chess, & Birch, 1968). The BSQ is summarized into nine subscale scores, one for each dimension of temperament. A higher score indicates a more ‘difficult’ temperament (highly active, more arrhythmic, withdrawn, slower to adapt, more intense, negative mood, less persistent, highly distractible, and more sensitive), whereas a lower score indicates an ‘easier’ temperament (less active, more rhythmic, more approaching, more adaptable, mild, positive mood, highly persistent, less distractible, and nonreactive; McDevitt & Carey, 1996). Psychometric properties are published both in a study by McDevitt and Carey (1978) and in the BSQ manual (McDevitt & Carey, 1996).

Sensory features. Four sensory measures were used in the current study, including two parent-report measures, and two observed measures. The Sensory Profile (SP; Dunn, 1999) is a commonly used 125-item parent report measure of frequency of a child’s sensory responses. The Sensory Profile uses a Likert Scale ranging from 1 (always) to 5 (never), with items falling into eight categories: auditory, visual, taste/smell, movement, body position, touch, activity level, and emotional/social. The SP has been found to have high levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .47 to .91). The SP is used to measure severity of sensory processing problems across clinical populations including children with autism based on a sample of children between the ages of 3 and 14 (Kientz & Dunn, 1997).

The Sensory Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ; Baranek et al., 2006; Little et al., 2011) is s 36-item caregiver questionnaire that focuses on frequency of sensory responses in young children with ASD and other DD. The SEQ uses a 5-point Likert Scale to measure the frequency (1 = almost never to 5 = almost always) of parent-reported behaviors across a variety of sensory modalities, and grouped by response patterns of hyperresponsiveness, hyporesponsiveness, and sensory seeking. The SEQ is an internally consistent and reliable caregiver report measure. In a sample of children ages 6–72 months old the SEQ showed high overall internal consistency (Chronbach’s alpha = .80; Little et al., 2011). In a sample children with autism ages 6–55 months old the SEQ showed high test-retest reliability (interclass correlation coefficient = .92; Little et al., 2011). The SEQ was found to discriminate autism from developmental delay and typical development in a known-groups validity study of children 5–80 months old (Baranek et al., 2006).

The Tactile Defensiveness and Discrimination Test (TDDT-R; Baranek, 1998; Baranek et al., 2007; Baranek & Berkson, 1994) is an observational play-based assessment of sensory responsiveness, focused specifically on tactile processing. The TDDT-R uses a 4-point scale for defensiveness (0 = no negative reaction to 3 = severe negative reaction), and offers the response items “correct” or “incorrect” for the discrimination scale. The TDDT-R has been validated with children with autism and DD in two other studies for children ages 5–7 years old (Baranek et al., 2007) and 7–14 years old (Baranek & Berkson, 1994).

The Sensory Processing Assessment for Young Children (SPA; Baranek, 1999) is a play-based observational assessment used to identify approach/avoidance behaviors in response to novel sensory toys, orienting/habituating responses to sensory stimuli, and initiation of novel action strategies, as well as stereotyped behaviors. The SPA was been developed specifically for young children with autism and related DD in the age group of interest. The SPA is a reliable assessment tool, with intraclass correlation coefficients (agreement for two raters across items in each scale) of .87 for aversion (tapping hyperresponsiveness) and .90 for habituation (tapping hyporesponsiveness) in a sample of 34 children 5–83 months old (Baranek et al., 2007).

Conceptual and Empirical Validation of Sensory Construct & Scoring Methods

Items from each of the four sensory measures (SEQ, SP, SPA, and TDDT-R) were rigorously evaluated using a combined conceptual and empirical approach to validate the three sensory dimensional constructs of interest (hyperresponsiveness, hyporesponsiveness, and sensory seeking). Content validation ensured that all items included in the final analyses measuring each sensory construct were in conceptual agreement (Beck & Gable, 2001; Grant & Davis, 1997). Three Ph.D. researchers and one doctoral student with expertise in the clinical manifestations of sensory features in ASD followed established guidelines to conduct an exhaustive review of all items (Blue, Marrero, & Black, 2008; Fitzner, 2007; Gould, Moore, McGuire, & Stebbins, 2008) and proceeded in two steps: (a) researchers were divided into two pairs and each pair categorized items for two of the four assessments (to ensure that each assessment was reviewed by at least two evaluators) with each evaluator categorizing items independently; and (b) evaluators compared results and resolved any disagreements via a consensus across evaluators. Results of this process were consistent with the original conceptual models outlined by the primary authors of the instruments.

The SP contributed a total of 64 items (hyporesponsiveness (10), hyperresponsiveness (29), sensory seeking (25)), the SEQ contributed 33 items (hyporesponsiveness (6) hyperresponsiveness (14) sensory seeking (13)), the TDDT-R contributed 39 items (hyporesponsiveness (1) hyperresponsiveness (31) sensory seeking (7)), and the SPA contributed 31 items (hyporesponsiveness (7) hyperresponsiveness (17) sensory seeking (7)). Scores were transformed to ensure each item was scored on a 5-point scale with concordant valence across all four assessments (score of 1 being least severe sensory symptoms and a score of 5 being most severe). A mean score was derived for each sensory construct on each separate assessment.

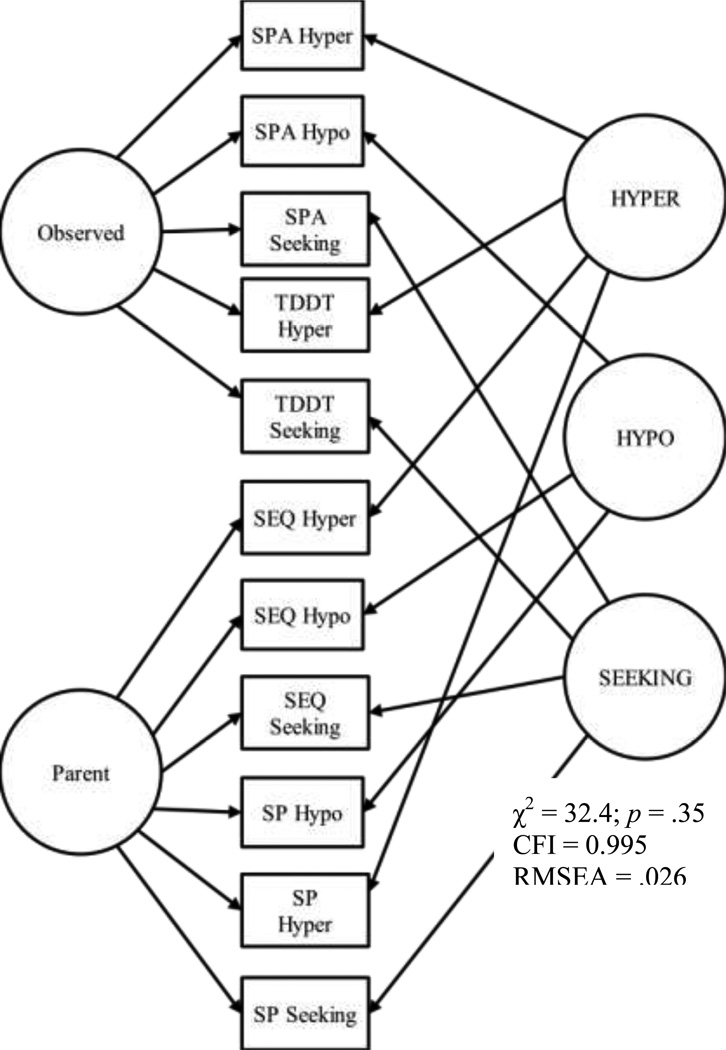

A factor analytic model was used to confirm the three sensory constructs (hyporesponsiveness, hyperresponsiveness, and sensory seeking) using the four assessments described above (SP, SEQ, TDDT, SPA), and adjusting for rater bias. The CFA model enables measurement that yields stronger construct scores that are more accurate than a single measure. By using two parent and two direct observation measures to estimate each sensory construct, the construct score estimates were are able to control for rater bias. A detailed description of the methodology is also reported in Watson et al. (2011). A graphic depiction of the final model is illustrated in Figure 1. The goal of CFA is to determine how well a proposed model explains observed data. Fit indices indicated this model fit the data well. A non-significant χ2 indicated that the implied and observed covariances were not significantly different, a RMSEA value of less than 0.06 indicated a relatively small amount of error, and a CFI value close to 1 indicated a good fit compared to a null model. From this model factor scores were derived for all children. These factor scores were then used in all subsequent analyses of sensory features.

Figure 1.

Factor Score Model

Statistical Analysis

Temperament of ASD group

The two research questions were addressed through statistical analysis. The first question considered how the ASD group compared to the DD and typically developing groups with respect to the nine dimensions of temperament. An ANOVA with follow-up pair-wise comparisons was used to compare the ASD, DD and the typically developing (TD) children from the original BSQ normative study (Carey & McDevitt, 1978).

Temperament and sensory features

To investigate the second research question of how sensory features relate to temperament in children with ASD, nine repeated measures regression models were fit, one for each dimension of temperament, with 3 repeated measures per subject for the sensory constructs (hyporesponsiveness, hyperresponsiveness, and sensory seeking). Each model included a continuous dependent variable (sensory construct score) and an independent variable (a categorical variable indicating which sensory construct the sensory score represented), as well as covariates (temperament, mental age, chronological age, and gender). Interactions between the sensory score indicator, temperament, and group were investigated to assess for variability in the relationship between the sensory score and temperament. Two-degree-of-freedom F-tests were used to determine if the relationship between temperament and sensory features varied significantly among the three sensory constructs. Non-significant interactions were removed to aid interpretation. Construct specific effects were only examined if the 2-way interaction between the categorical sensory construct variable (independent variable) and temperament (covariate) was significant; otherwise only main effects are reported. This statistical approach is a known variant of the MANOVA approach in that it relaxes the assumptions about sphericity (e.g., it does not assume that the correlations between hyporesponsiveness, hyperresponsiveness and sensory seeking are equal; Gueorguieva, Krystal, 2004).

Results

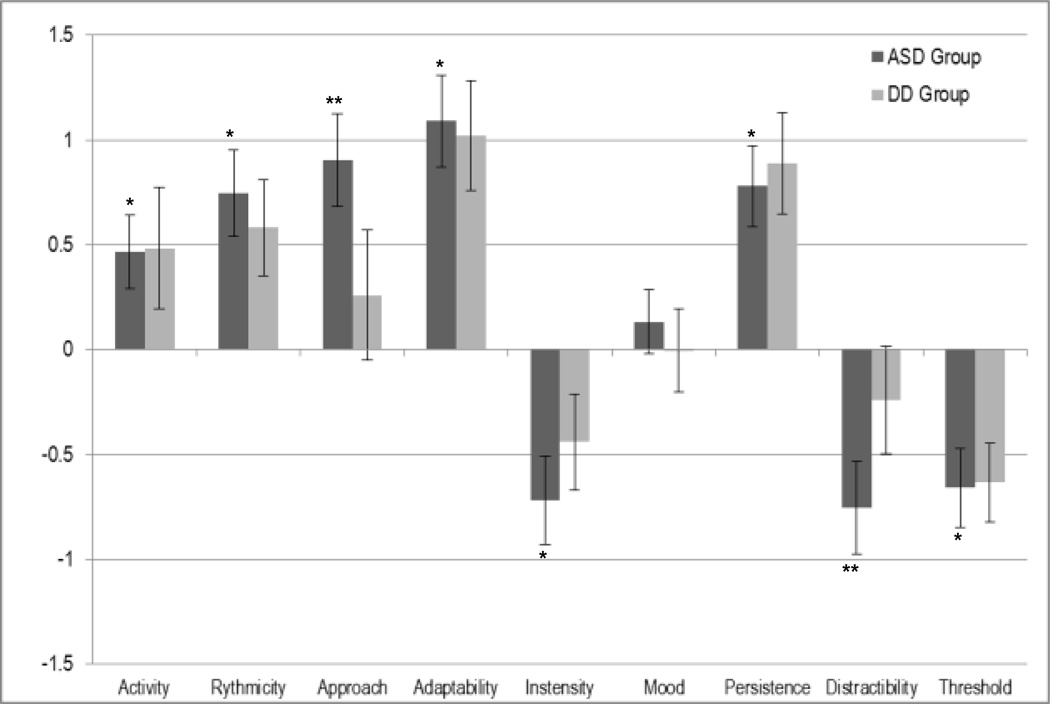

The ASD group displayed BSQ subscale scores that were significantly different from typically developing children and more similar to children with DD (see Table 2 and Figure 2). The ASD group differed significantly from the typically developing normative group (Carey & McDevitt, 1978) on eight out of nine BSQ subscales. Consistent with hypotheses, significant differences included activity (p < .001), rhythmicity (p < .001), approach (p < .001), adaptability (p < .001), intensity (p < .001), persistence (p < .001), distractibility (p < .001), and threshold (p < .001). Only the mood subscale did not display significant differences between the ASD group and the typically developing group. The ASD group significantly differed from the DD group on approach (p = .018), showing more withdrawal, and on distractibility (p = .004), showing less distractibility.

Table 2.

Results of ANOVA and Follow-up Tests for Temperament Comparison

| Temperament Subscale |

Model | Follow-up Tests | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD × TD | DD × TD | DD × TD | ||||||

| F2,434 | p | t | p | t | p | t | p | |

| Activity | 13.96 | <.0001 | 4.26 | <.0001 | −0.11 | .91 | 3.56 | .0004 |

| Rhythmicity | 34.61 | <.0001 | 7.37 | <.0001 | 1.06 | .29 | 4.63 | <.0001 |

| Approach | 22.71 | <.0001 | 6.69 | <.0001 | 3.15 | <.01 | 1.55 | 0.12 |

| Adaptability | 72.81 | <.0001 | 10.12 | <.0001 | 0.43 | .67 | 7.61 | <.0001 |

| Intensity | 30.69 | <.0001 | −7.30 | <.0001 | −1.87 | .06 | −3.60 | .0004 |

| Mood | 0.97 | 0.38 | ||||||

| Persistence | 48.88 | <.0001 | 7.69 | <.0001 | −0.69 | .49 | 0.69 | .49 |

| Distractibility | 20.71 | <.0001 | −6.36 | <.0001 | −2.88 | .004 | −1.61 | .10 |

| Threshold | 39.38 | <.0001 | −7.37 | <.0001 | −0.19 | .85 | −5.69 | <.0001 |

Note: All regression models control for mental age, chronological age, and gender. Significant p-values (p < .05) are bolded.

Figure 2.

Mean BSQ Subscale Z-Scores for ASD (n = 54) and Developmental Delay (n = 33) Groups Compared to Typically Developing Children (n = 350)

Note: Z-scores are based on norms from typically developing children (Carey & McDevitt, 1978). Bars characterize ASD and developmental disability groups in terms of standard deviations relative to typically developing children. Scores greater than 0 indicate a more ‘difficult’ temperament than typically developing children, while scores less than 0 indicate an ‘easier’ temperament than typically developing children. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for means calculated from a normal distribution.

*autism group subdomain score is significantly different than normed score for typically developing children;

**autism group subdomain score is significantly different than both the normed score for typically developing children and score for the developmental disability group.

Next, the relationship between temperament and sensory features was considered for the ASD group (n = 54). There were main effects for the temperament subscales of approach and mood, such that increased sensory features (for the three sensory constructs combined) were associated with increased withdrawal (on the approach subscale; p = .002) and more negative mood (p = .014). Three regression models yielded significant F-tests for interaction terms (temperament by sensory construct) specifically on the dimensions of adaptability, threshold, and distractibility. Follow-up tests revealed significant associations between sensory hyporesponsiveness and slowness to adapt (on the adaptability dimension; p = .001), low reactivity (on the threshold dimension; p = .038) and low distractibility (p < .001). Contrary to our hypotheses, hyperresponsiveness and sensory seeking constructs were not differentially related to any of the dimensions of temperament. Complete results from the regression analysis are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Coefficients for Regression Models with Sensory Constructs Predicting Temperament Subscales

| Temperament Subscale |

Hypothesized Relationships |

Test of Temp × Construct |

Overall | Sensory Construct | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypo | Hyper | Seeking | |||||||||

| F2,48 | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | ||

| Activity | Hypera, Seekinga | 2.71 | .08 | −0.02 | .82 | ||||||

| Rhythmicity | Hypera | 0.28 | .76 | 0.04 | .57 | ||||||

| Approach | Hypoc, Hyperc, Seekingc | 0.93 | .40 | 0.32 | .002 | ||||||

| Adaptability | Hypob, Hypera | 4.51 | .02 | 0.38 | .001 | 0.16 | .12 | −0.01 | .92 | ||

| Intensity | Hypoa, Hypera | 2.09 | .14 | 0.03 | .70 | ||||||

| Mood | Hyperc | 2.41 | .10 | 0.28 | .01 | ||||||

| Persistence | Hypoa, Seekinga | 1.52 | .23 | 0.07 | .38 | ||||||

| Distractibility | Hypob, Hypera | 7.67 | .001 | −0.46 | <.0001 | −0.16 | .17 | 0.08 | .52 | ||

| Threshold | Hypob, Hypera | 5.71 | .006 | −0.28 | .04 | 0.17 | .15 | 0.05 | .70 | ||

Note: All regression models control for mental age, chronological age, and gender. Significant p-values (p < .05) are bolded.

hypothesized relationship was not statistically significant;

hypothesized relationship was statistically significant;

construct was not differentially related to subscale, but was part of an overall effect

Discussion

Temperament Profiles in ASD

Based on previous characterizations of temperament in children with ASD using Thomas and Chess’ model (Bailey, et al., 2000; Bieberich & Morgan, 2004; Garon et al., 2009; Hatton, et al., 1999; Hepburn & Stone, 2006), we hypothesized that the ASD group would be more active, more withdrawn, less adaptive, less intense in their reactions, and less sensitive to environmental stimuli compared to the typically developing group. It also was expected that the ASD group would be more withdrawn on the approach dimension compared to the DD group. Although all of these hypotheses were confirmed, the ASD group was distinct from the typically developing group on additional temperament dimensions not previously documented in the literature. These included lower rhythmicity and lower distractibility.

The temperament scores of the ASD group closely mirrored the findings in the only other published study to describe the BSQ temperament profile of a large group (n = 110) of children with ASD in detail (Hepburn & Stone, 2006), demonstrating replication of their findings across all but one subscale. The convergent findings across studies suggest that dimensions of temperament, as a whole, provide useful information and distinguish ASD children, as a group, from children with typical development, even when controlling for developmental variables and gender.

However, previous studies using the BSQ have not directly compared temperament in children with ASD to children with other DD; thus, the specificity of these temperament profiles to ASD was unknown. Our results indicated that distinctions between ASD and DD were less apparent than they were with the TD comparison group. Nonetheless, approach and distractibility were two temperament scales displaying statistically significant differences between these two clinical groups. The difference between the ASD and DD groups in approach was hypothesized. Differences in approach may reflect core deficits in ASD (APA, 2000), particularly with respect to aberrant responses to novel objects, people, and situations. Additionally, statistically significant differences emerged between the two groups on the distractibility scale, which was unanticipated. Research suggests that orienting and attention mechanisms may be disrupted in ASD, causing perseverative patterns in visual fixation and difficulties in disengagement from a central stimulus (Landry & Bryson, 2004); these deficits may manifest as over-focused attention or less distractibility. Thus, these two dimensions (distractibility and approach) may reflect a specific temperamental profile of children with ASD (as a group) that reflects core features of this disorder, and has particular utility in differential diagnosis for children with ASD versus other DD.

Associations between Sensory Features and Temperament in ASD

The two dimensions that distinguished the ASD group from the DD group (distractibility and approach) were significantly associated with sensory responsiveness. These associations are of particular interest, because differences in sensory responsiveness may explain differences in temperament that are specific to ASD.

As hypothesized, hyporesponsiveness was most associated with distractibility. Two explanations are considered. First, children who are less responsive to sensory stimuli may simply be more difficult to distract. An alternative explanation may be that some children with ASD who are hyporesponsive may be difficult to engage at all, or may be overfocused on irrelevant stimuli and have trouble disengaging attention (Ben-Sasson et al., 2008; Landry & Bryson, 2004). Although the BSQ distractibility subscale is intended to measure how external stimuli ‘distract’ a child from whatever behavior s/he is currently engaged in, all of the questions in this subscale assume (perhaps incorrectly) that the child is already engaged before the ‘distractor’ is presented. Experimental designs using gap-overlap tasks could shed more light on disaggregating aspects of visual engagement and disengagement that may be related to specific neural mechanisms (Van der Geest, Kemner, Verbaten, & Van Engeland, 2002) and testing differential associations with sensory responsive patterns and temperament profiles in children with ASD.

Slower, or more cautious approach, was also associated with increased sensory features across all three sensory constructs. Approach is defined as a child’s “initial reaction to any new stimulus, be it food, people, places, toys, or procedures” (Thomas, Chess, & Birch, 1968, p. 20). Thus, more extreme sensory features were associated with increased withdrawal around novel physical or social events. For example, a child who is hyporesponsive may not register or attend to a new sensory stimulus in the environment and would be less likely to approach that stimulus or initiate joint attention with others in response to that stimulus. In contrast, a child who is hyperresponsive might approach less to avoid or attenuate an aversive sensory response.

Other dimensions of temperament that did not distinguish the ASD group from the DD group (adaptability, mood, and threshold) were also significantly associated with sensory responsiveness. While these associations may not explain ASD-specific temperament, they do illuminate potential intersections between sensory features and temperament in children with developmental disabilities including ASD.

Hyporesponsiveness was associated with adaptability in the predicted direction (slowness to adapt). This suggests that children who have atypical sensory responsiveness (specifically more hyporesponsive behaviors) may have a narrower optimal level of engagement with their environment and thus may take a longer time to adjust to change, and modify their behaviors in response to social expectations (Baranek et al., 2006). This finding is consistent with other literature describing behavioral rigidities and over-adherence to rules and rituals (Mooney et al., 2009; Turner et al., 2009; Volkmar et al., 2004), suggesting that cognitive rigidity and sensory-based behaviors are strongly associated and may have a common neurological cause (Carcani-Rathwell et al., 2006).

Mood was significantly correlated with all three sensory response patterns, suggesting that high levels of sensory features, regardless of the nature of these features, are associated with increased withdrawal and more negative mood. Several studies demonstrate that a pattern of sensory hyperresponsiveness is characterized by aversion to stimuli often expressed by negative emotional reactions (Baranek et al., 2006; Ben-Sasson et al., 2008; Kientz & Dunn, 1997) and/or anxiety (Green, Ben-Sasson, Soto, & Carter, 2011), which is consistent with the presence of increased negative mood, as we hypothesized. However, it was surprising that the other two sensory response patterns (hyporesponsiveness and seeking) were also significantly associated with more negative mood. Although the mood subscale on the BSQ taps how a child responds affectively (positively or negatively to a given stimulus), closer inspection of the items indicated that the majority (8 of the 12 items) involved a social stimulus. Thus, it is plausible that children with ASD who display high levels of hyporesponsive behaviors would be perceived by caregivers as having less positive affect during social situations, even if they do not show an aversive reaction to the social stimulus per se. Similarly, it is plausible that high levels of sensory seeking behaviors may result in negative emotional reactions if caregivers attempt to engage the child with stimuli other than the child’s own idiosyncratic fascinations. It was noteworthy that despite the tendency for sensory seeking behaviors to be construed as pleasurable in some biographical accounts of persons with ASD (e.g., Grandin & Groden, 2006) this pattern was associated with negative rather than positive mood on the temperament measure.

We hypothesized that the threshold of responsiveness dimension of temperament would be correlated with both sensory hypo- and hyperresponsive patterns. We found a significant association between the threshold subscale and hyporesponsiveness, but not between threshold and hyperresponsiveness. Because children with ASD display both hyporesponsive and hyperresponsive behaviors, but tend toward more hyporesponsive patterns that distinguish them from other groups (Baranek et al., 2006), collapsing these constructs onto a single continuum on the temperament measure may have obscured the association of threshold with hyperresponsiveness more so than for hyporesponsiveness.

Contrary to expectations, we did not find statistically significant associations between some dimensions of temperament (activity, rhythmicity, intensity) and patterns of sensory responsiveness. The absence of certain associations was especially surprising. For example, one would expect that sensory responsiveness would be strongly associated with activity level, or the intensity of response to a given stimuli. Despite the logic of this expectation, the findings appear to suggest that some dimensions of temperament have less of a relationship with sensory processing in children with ASD than others. One plausible explanation for the lack of associations with all temperament dimensions is measurement error. The measures of different temperament dimensions are extremely variable in their reliability as measured by test-retest (r = 0.67–0.94; McDevitt & Carey, 1996). Perhaps the original hypothesis that all temperament dimensions are associated with sensory constructs is true, but that some associations were obscured as a result of less reliable measures. Overall, the trend of the results seems to support this. Four of the five most reliable measures of temperament dimensions (r > .80; McDevitt & Carey) were found to be associated with sensory constructs, while three of the four least reliable measures (r ≤ .80; McDevitt & Carey) were not found to be associated with sensory constructs.

It was also surprising that there were no statistically significant (differential) main effects between hyperresponsiveness or sensory seeking and any of the temperament subscales. However, it appears from the results of the analyses (Table 3) that hyperresponsiveness may in fact be related to some temperament traits, but that the statistical power and precision of measurement in this study were not sufficient to detect a statistically significant association. Sensory seeking, on the other hand, does not appear to be related to most of the temperament subscales at all. While hyporesponsiveness and hyperresponsiveness are both associated with sensory seeking behaviors and temperament, sensory seeking and temperament are not strongly related to each other. Perhaps sensory seeking behavior is a strategy that enables children with autism to modulate between hypo- and hyperreponsiveness (Baranek et al., 2007), but the use of this strategy is independent of child temperament.

Implications for shared mechanisms underlying sensory features and temperament traits in ASD

Two temperament traits, approach and distractibility, distinguish the ASD group from the DD and typical group, and are related to sensory responsiveness. These associations may offer insight into possible shared mechanisms that underlie sensory features and temperament traits in ASD.

As mentioned previously, withdrawal (particularly to social stimuli) in children with ASD that was found to be associated with sensory responsiveness, generalized across the three sensory patterns measured in this study. Physiological studies of infants have directly linked dysregulation in stress-sensitive systems (e.g., hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical; sympathetic adrenomedullary) to sensory reactivity and arousal (particularly hyperresponsiveness), as well as increased behavioral inhibition to novelty and fearfulness later in childhood (for a review see Martin & Fox, 2006). In children with ASD, such temperamental characteristics may be more extreme than in comparison groups because of biologically-based differences affecting neural connectivity. In addition, children with ASD may be less likely to benefit from the social context to moderate their responses in stressful or fearful situations. Future studies could address limitations in parent-report questionnaires by including physiological measures (e.g., cortisol, electrodermal responses, heart rate, electroencephalography) to further determine the role of stress reactivity and/or fear conditioning as a common underlying cause of sensory features (across constructs) that may be specifically linked with social withdrawal.

Neuroscience research suggests that emotionally salient events may modulate attention and enhance sensory processing not only for negative events but also potentially for positive events (Vuilleumier, 2005). Thus, difficulties in the integration of neural mechanisms supporting attention modulation and/or affective salience (e.g., amygdala with projections to various subcortical and cortical networks) may have particular relevance for understanding linkages between a pattern of sensory hyporesponsiveness, and several dimensions of temperament (e.g., less distractibility and less approach) found in this study. Deficits in the amygdala and hippocampal regions are often implicated in the pathogenesis of core features in ASD (Baron-Cohen et al., 2000; Dalton et al., 2005; Dawson et al., 2004, Schulkin, 2007; Sweeten, Posey, Shekhar, & McDougle, 2002). Thus, further research testing how emotional biases affect the selection of sensory inputs in children with ASD who demonstrate high levels of sensory hyporesponsiveness as well as over-focused attention, and social withdrawal may help elucidate common neural mechanisms.

Furthermore, neurologically-based differences in stimulus-reward systems in ASD may play a central role in disruption of motivational processes that support approach to novel sensory stimuli, positive emotion, and increased exploration (Dawson, Osterling, Rinaldi, Carver, & McPartland, 2001). In typical development, brain circuitry associated with reward processing may be shaped to guide responses to environmental stimuli through a complex integrative process. Encoding responses to stimuli as pleasant or aversive in turn guides behavior towards that particular type of stimulus, whether it is social or non-social. Typically developing children develop neural pathways that naturally reinforce sensations of pleasure and reward, with the exploration of their social environment and interactions with other people effectively shaping the way that children behave and respond to their environment (Rubia et al., 2006). Children with ASD, however, tend to have difficulty forming similar rules for stimulus-reward associations, especially in regard to social information (Dawson, Osterling, Rinaldi, Carver, & McPartland, 2001; Dawson, Meltzoff, Osterling, Rinaldi, & Brown, 1998; Dawson et al., 2005; Schultz, 2005). Further research in this area may illuminate how the lack of more positive, rewarding associations with social experiences can negatively impact these reward networks that might underlie both sensory features and temperament.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is reliance on a single parent-report instrument to measure temperament based on the model developed by Thomas and Chess. Because the BSQ was originally developed and tested on typically developing children (BSQ; McDevitt & Carey, 1996), some of the subscales may not capture information for children with ASD in the way that the developers of the BSQ originally intended. Studies using other models and multimodal measures may have provided more comprehensive insights for this population. For example, temperament questionnaires rooted in the model created by Rothbart and Derryberry (1981), which include regulation as a key component modulating reactivity, have been shown to predict overall autism symptomology. Finally, our study presents a cross-sectional representation of temperamental characteristics in children ages 36–84 months; longitudinal studies are needed to determine the extent to which temperament traits (and likewise their associations with sensory features and core features of ASD) are stable over time.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Our findings indicate that children with ASD as a group can be distinguished on the basis of two temperament characteristics (lower distractibility, and poorer approach) from children with DD as well as TD children. Moreover, associations between sensory responsiveness and five of the nine Thomas and Chess (1968) dimensions of temperament suggest much overlap between these constructs with implications for understanding core features of ASD, particularly with respect to social withdrawal, negative affect, and over-focused attention. Further research is needed to determine shared biological mechanisms that support sensory processing, affect, and attention regulation systems and may be linked to later developmental manifestations of personality and core features of ASD. In particular, longitudinal studies with high risk infant populations could determine if early differences in sensory processing and temperament may be risk factors for later phenotypic progressions in ASD including deficits in social motivational processes.

Identification of associations between sensory response patterns, temperament traits, and core features of ASD may also have implications for intervention. Future studies may also take into consideration parental perceptions of their child’s temperament and teaching responsive strategies that are more likely to promote social engagement, adaptation, and learning. Likewise, focus on shifting parent’s negative perceptions of their child’s behaviors towards more positive characteristics (Boström, Brorberg & Hwang, 2010) may be helpful particularly for children with high levels of unusual sensory features concomitant with difficult temperament (e.g., negative mood; social withdrawal). As associations among core and associated features of ASD are increasingly identified and better understood, interventions will be optimized to allow for improved outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank the families that participated in this study. This study was made possible by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD042168).

References

- Aron EN, Aron A. Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(2):345–368. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, D.C.: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Hatton DD, Mesibov G, Ament N, Skinner M. Early development, temperament, and functional impairment in autism and fragile X syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(1):49–59. doi: 10.1023/a:1005412111706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AEZ, Lane A, Angley MT, Young RL. The relationship between sensory processing patterns and behavioural responsiveness in autistic disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(5):867–875. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT. Tactile defensiveness and discrimination test: Revised. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 1998. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT. Sensory processing assessment for young children (SPA) University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 1999. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT. Efficacy of sensory and motor interventions for children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32(5):397–422. doi: 10.1023/a:1020541906063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, Berkson G. Tactile defensiveness in children with developmental disabilities: Responsiveness and habituation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24(4):457–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02172128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, Boyd BA, Poe MD, David FJ, Watson LR. Hyperresponsive sensory patterns in young children with autism, developmental delay, and typical development. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2007;112(4):233–245. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[233:HSPIYC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, David FJ, Poe MD, Stone WL, Watson LR. Sensory Experiences Questionnaire: discriminating sensory features in young children with autism, developmental delays, and typical development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(6):591–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Ring HA, Bullmore ET, Wheelwright S, Ashwin C, Williams SCR. The amygdala theory of autism. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24(3):355–364. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Cermak SA, Orsmond GI, Tager-Flusberg H, Carter AS, Kadlec MB, Dunn W. Extreme sensory modulation behaviors in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;61(5):584–592. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.5.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Cermak S, Orsmond G, Tager-Flusberg H, Kadlec M, Carter A. Sensory clusters of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Differences in affective symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(8):817–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieberich AA, Morgan SB. Self-regulation and affective expression during play in children with autism or Down syndrome: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34(4):439–448. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000037420.16169.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boström P, Broberg M, Hwang C. Different, difficult or distinct? Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of temperament in children with and without intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2010;54(9):806–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd BA, Baranek GT, Sideris J, Poe MD, Watson LR, Patten E, Miller H. Sensory features and repetitive behaviors in children with autism and developmental delays. Autism Research. 2010;3(2):78–87. doi: 10.1002/aur.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson SE. Brief report: Epidemiology of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1996;26(2):165–167. doi: 10.1007/BF02172005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. A temperament theory of personality development. Oxford: Wiley-Interscience; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. Temperament: Early developing personality traits. Hillsdale, NJ: Eralbaum; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Carcani-Rathwell I, Rabe-Hasketh S, Santosh PJ. Repetitive and stereotyped behaviours in pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(6):573–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chess S, Thomas A. Temperament: Theory and practice. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton KM, Nacewicz BM, Johnstone T, Schaefer HS, Gernsbacher MA, Goldsmith H, Alexander AL, Davidson RJ. Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(4):519–526. doi: 10.1038/nn1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Watling R. Interventions to facilitate auditory, visual, and motor integration in autism: A review of the evidence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(5):415–421. doi: 10.1023/a:1005547422749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Meltzoff AN, Osterling J, Rinaldi J, Brown E. Children with autism fail to orient to naturally occurring social stimuli. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1998;28(6):479–485. doi: 10.1023/a:1026043926488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Osterling J, Rinaldi J, Carver L, McPartland J. Brief report: Recognition memory and stimulus-reward associations: Indirect support for the role of ventromedial prefrontal dysfunction in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001;31(3):337–341. doi: 10.1023/a:1010751404865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Webb SJ, Carver L, Panagiotides H, McPartland J. Young children with autism show atypical brain responses to fearful versus neutral facial expressions of emotion. Developmental Science. 2004;7(3):340–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGangi GA, Breinbauer C, Roosevelt JD, Porges S, Greenspan S. Prediction of childhood problems at three years in children experiencing disorders of regulation during infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2000;21(3):156–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W. The impact of sensory processing abilities on the daily lives of young children and their families: A conceptual model. Infants and Young Children. 1997;9:23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W. Sensory profile. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W. The sensations of everyday life: Empirical, theoretical, and pragmatic considerations. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;55(6):608–620. doi: 10.5014/ajot.55.6.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LC, Ho HH, Eaves DM. Subtypes of autism by cluster analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24(1):3–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02172209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck H. Personality and extra-sensory perception. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research. 1967;44(732):55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Polak CP. The role of sensory reactivity in understanding infant temperament. In: DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A, editors. Handbook of infant, toddler, and preschool mental health assessment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, Schmidt LA. Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001;72(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garon N, Bryson SE, Zwaigenbaum L, Smith IM, Brian J, Roberts W, Szatmari P. Temperament and its relationship to autistic symptoms in a high-risk infant sib cohort. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(1):59–78. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH. Studying temperament via construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Development. 1996;67(1):218–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez CR, Baird S. Identifying early indicators for autism in self-regulation difficulties. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2005;20(2):106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gomot M, Belmonte MK, Bullmore ET, Bernard FA, Baron-Cohen S. Brain hyper-reactivity to auditory novel targets in children with high-functioning autism. Brain. 2008;131(9) doi: 10.1093/brain/awn172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin T. Stopping the constant stress: A personal account. In: Baron MG, Groden J, Groden G, Lipsitt LP, editors. Stress and coping in autism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Green SA, Ben-Sasson A, Soto TW, Carter AS. Anxiety and Sensory Over-Responsivity in Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Bidirectional Effects Across Time. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(3):310. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton DD, Bailey DB, Hargett-Beck MQ, Skinner M, Clark RD. Behavioral style of young boys with fragile X syndrome. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1999;41(9):625–632. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299001280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn SL, Stone WL. Using Carey Temperament Scales to assess behavioral style in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36(5):637–642. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0110-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Tessner K, Wang S, Carter H, McDermott M. Temperament at 5 years of age predicts amygdala and orbitofrontal volume in the right hemisphere in adolescence. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2010;182(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton CL, Harper JD, Kueker RH, Lang AR, Abbacchi AM, Todorov A, LaVesser PD. Sensory responsiveness as a predictor of social severity in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40(8):937–945. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0944-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton C, Graver K, LaVesser P. Relationship between social competence and sensory processing in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2007;1(2):164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Kana RK, Minshew NJ. Functional and anatomical cortical underconnectivity in autism: evidence from an FMRI study of an executive function task and corpus callosum morphometry. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17(4):951. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L, et al. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous child. 1943;2(3):217–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kientz MA, Dunn W. A comparison of the performance of children with and without autism on the Sensory Profile. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1997;51(7):530–537. doi: 10.5014/ajot.51.7.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristal J. The temperament perspective: Working with children’s behavioral styles. Paul H. Brookes Pub. Co.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Landry R, Bryson SE. Impaired disengagement of attention in young children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(6):1115–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane AE, Young RL, Baker AEZ, Angley MT. Sensory processing subtypes in autism: Association with adaptive behavior. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40(1):112–122. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0840-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss M, Saulnier C, Fein D, Kinsbourne M. Sensory and attention abnormalities in autistic spectrum disorders. Autism. 2006;10(2):155–172. doi: 10.1177/1362361306062021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little LM, Freuler AC, Houser MB, Guckian L, Carbine K, David FJ, Baranek GT. Psychometric Validation of the Sensory Experiences Questionnaire. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011;65(2):207–210. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2011.000844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Pickles A, Rutter M. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(3):205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24(5):659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JN, Fox NA. Temperament. In: McCarney K, Phillips D, editors. Blackwell Handbook of Early Childhood Development. Malken, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. pp. 26–146. [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. Child temperament and educational outcomes. In: Pellegrini AD, editor. Psychological bases for early education. London: John Wiley & Sons; 1988. pp. 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt SC, Carey WB. The measurement of temperament in 3–7 year old children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1978;19(3):245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1978.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt S, Carey W. Manual for the Behavioral Style Questionnaire. Scottsdale, AZ: Behavioral-Developmental Initiatives; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney EL, Gray KM, Tonge BJ. Early features of autism. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;15(1):12–18. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney EL, Gray KM, Tonge BJ, Sweeney DJ, Taffe JR. Factor analytic study of repetitive behaviours in young children with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39(5):765–774. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedlow R, Sanson A, Prior M, Oberklaid F. Stability of maternally reported temperament from infancy to 8 years. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(6):998. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds S, Lane SJ. Diagnostic validity of sensory over-responsivity: a review of the literature and case reports. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(3):516–529. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers JW, Stoneman Z. Child temperaments, differential parenting, and the sibling relationships of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(9):1740–1750. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0560-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins DL, Fein D, Barton ML, Green JA. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers: An initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001;31(2):131–144. doi: 10.1023/a:1010738829569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Hepburn S, Wehner E. Parent reports of sensory symptoms in toddlers with autism and those with other developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33(6):631–642. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000006000.38991.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S. Annotation: What do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(12):1255–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Children’s behavior questionnaire standard form. University of Oregon; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology. 5th ed. Vol 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 1998. pp. 105–176. Social, emotional, and personality development. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Derryberry D. Development of individual differences in temperament. In: Lamb AL, Brown ME, editors. Advances in developmental psychology. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 37–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Smith AB, Woolley J, Nosarti C, Heyman I, Taylor E, Brammer M. Progressive increase of frontostriatal brain activation from childhood to adulthood during event-related tasks of cognitive control. Human Brain Mapping. 2006;27(12):973–993. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Schopler E. Autism and pervasive developmental disorders: Concepts and diagnostic issues. In: Schopler E, Mesibov GB, editors. Diagnosis and assessment in autism. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen SA, Miller LJ, Green KE. Pilot study of the sensory over-responsivity scales: assessment and inventory. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008;62(4):393–406. doi: 10.5014/ajot.62.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopler E, Reichler RJ, DeVellis RF, Daly K. Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1980;10(1):91–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02408436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulkin J. Autism and the amygdala: an Endocrine hypothesis. Brain and cognition. 2007;65(1):87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz RT. Developmental deficits in social perception in autism: the role of the amygdala and fusiform face area. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2005;23(2–3):125–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CB, Henderson HA, Inge AP, Zahka NE, Coman DC, Kojkowski NM, Hileman CM, Mundy PC. Temperament as a predictor of symptomotology and adaptive functioning in adolescents with high-functioning autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2009;39(6):842–855. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan M, Roberts J, Hatton D, Reznick J, Goldsmith H. Early temperament and negative reactivity in boys with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2008;52(10):842–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeten TL, Posey DJ, Shekhar A, McDougle CJ. The amygdala and related structures in the pathophysiology of autism. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;71(3):449–455. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talay-Ongan A, Wood K. Unusual sensory sensitivities in autism: A possible crossroads. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2000;47(2):201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Chess S. Temperament and development. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Chess A, Birch HG. Temperament and behavior disorders in children. New York: New York University Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Chess S, Birch HG, Hertzig ME, Korn S. Behavioral individuality in early childhood. New York: New York University Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Tomchek SD, Dunn W. Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;61(2):190–200. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. Annotation: Repetitive behaviour in autism: A review of psychological research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40(6):839–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Geest J, Kemner C, Verbaten M, Van Engeland H. Gaze behavior of children with pervasive developmental disorder toward human faces: a fixation time study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):669–678. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P. How brains beware: Neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9(12):585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR, Lord C, Bailey A, Schultz RT, Klin A. Autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):135–170. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watling RL, Deitz J, White O. Comparison of Sensory Profile scores of young children with and without autism spectrum disorders. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;55(4):416–423. doi: 10.5014/ajot.55.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LR, Patten E, Baranek GT, Poe M, Boyd BA, Freuler A, Lorenzi J. Differential associations between sensory response patterns and social-communication measures in children with autism and developmental disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2011;54:1562–1576. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0029). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb SJ, Jones EJH. Early identification of autism: Early characteristics, onset of symptoms, and diagnostic stability. Infants & Young Children. 2009;22(2):100. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0b013e3181a02f7f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersema JR, Roeyers H. ERP correlates of effortful control in children with varying levels of ADHD symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(3):327–336. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]