Abstract

Background

Human Rotavirus is a significant cause of severe gastroenteritis in infants and young children worldwide. In recent years, Rotavirus genotyping by RT-PCR has provided valuable information about the diversity of Rotaviruses circulating worldwide. The purpose of the present study is to monitor the prevalence of the different G types of Rotaviruses circulating in Shiraz, Southern Iran and detect any uncommon or novel types.

Methods

During the period from December 2007 to November 2008, a total of 138 stool samples were collected from children less than 5 years old who were hospitalized for acute gastroenteritis. Rotavirus-associated diarrhea was investigated in fecal specimens with enzyme immunoassays (EIA). Rotavirus-positive specimens were typed by the Nested RT-PCR and by using different types of specific primers.

Results

Out of the 138 collected samples, 34.78% (48 cases) tested positive for Rotavirus. The frequency of G1, G2 and G4 types was 6.25%, 2.08% and 27.08%, respectively. Mixed and non-typeable infections were detected in 33.34% and 31.25% of hospitalized children with acute diarrhea, respectively. This is the first time mixed Rotavirus infections with G1/G3 have been reported in Iran.

Conclusion

The high frequency of Rotavirus detection indicates the severity and the burden of Rotavirus disease may be able to reduce through the implementation of an effective vaccine and continual surveillance for the detection of Rotavirus genotypes circulating in other regions of Iran.

Regarding to the noticeable frequency of non-typeable and mixed infections, it is suggested to use the other specific primers and further studies to detection of other novel and unusual types.

Keywords: Human Rotavirus, Diarrhea, Hospitalized children, G types

Introduction

Human Rotavirus is the leading cause of severe gastroenteritis in infants and young children worldwide. An estimated 527,000 children less than five years of age die from Rotavirus gastroenteritis each year, with >85% of all Rotavirus-related deaths occurring in low-income countries of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.(1) Recent studies have shown that diarrhea causes 39% of childhood diarrhea hospitalizations and 5% of all deaths around the world in children less than 5 years old.(2) Nearly every child will infect with Rotavirus disease by age 5 years, one in five will require a clinic, one in 50 will be hospitalized, and one in 205 will die from this disease.(3) The clinical symptoms of Rotavirusncomplete.(15-18)

Studies of the genotyping in different regions of the world have indicated that G1-G4 and G9 types are the most common G types detected in children with Rotavirus gastroenteritis.(13, 19, 20) But in recent years, other rare or uncommon Rotavirus G types, such as G5, G8, G10, G11 and G12, have been reported in many countries.(6,14,21-24) In other diarrheal diseases, improvement of hygiene and sanitation may reduce incidences, but these measures are unlikely to be sufficient for Rotavirus control. Regarding to the high burden of Rotavirus infection, an effective Rotavirus vaccine program will reduce the morbidity associated with severe Rotavirus diarrhea. Before that program can be implemented, information is needed on the current burden of Rotavirus disease and the distribution and frequency of Rotavirus strains circulating in different regions of the country. The objectives of this study were to describe epidemiology of Rotavirus disease and determine the G types of Rotavirus circulating in children aged <5 years old with acute gastroenteritis in Shiraz, Iran.

Materials and Methods

Specimen collection

In this study a verbal consent was taken from either parent of the enrolled child prior to the interview and collection of stool samples. From December 2007 to November 2008, a total of 138 stool specimens were collected during the course of treatment from children under 5 years of age who were hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis in Shahid Dastgheib and Nemazee hospitals in Shiraz, Southern Iran. All the fecal specimens were transported to the infectious disease unit laboratory and stored at -70°C until the time of assay. All samples underwent only one cycle of thawing and freezing prior to characterization. A standard structured questionnaire was used to obtain the information regarding the age, sex, duration of hospital stay, severity of clinical symptoms and type of feeding (as breast/bottle feeding) for each case.

Rotavirus detection

All samples were screened for group A Rotavirus by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Rotavirus Ag ELISA, DRG, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Viral RNA extraction

Genomic RNA was extracted with a commercially available mixture of phenol and guanidine thiocyanate (RNX-Plus kit, CinnaGen, Tehran, Iran). Isolation of whole RNA was performed according to the manufacture’s protocol. Briefly, 500 µl RNX-Plus solution was mixed with a 20% stool suspension in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at a pH of 7.2 at a volume ratio of 3 to 1. After complete dissociation of nucleoprotein complexes, chloroform was added to the mixture followed by vigorous shaking and centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The upper aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube and the RNA precipitated by mixing it with isopropanol. The supernatant was removed and the RNA pellet was washed once with 75% ethanol. The RNA pellet was then briefly air dried and dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) treated water.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

Briefly, 5 µl of dsRNA was added to a mix of DMSO, 5X RT buffer, dNTPs, primers Beg9, End9,(25) and DW, denatured at 97°C for 5 min. Then RT enzyme and RNase inhibitor were added to make a final volume of 20 µl. The RT-PCR reaction was carried out for 60 min at 42°C to produce the complementary (cDNA) used for PCR amplification Rotavirus.

Nested multiplex PCR for G genotyping

The G-typing was performed according to Rotavirus detection and typing protocol provided by WHO.(25) Briefly, the first round VP7 consensus PCR was carried out with 10 μl of cDNA in 40 μl of the VP7 reagent mixtures. The cycling parameters used were: 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 42°C for 2 min, 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The second round VP7 multiplex PCR was carried out with 5 μl of first round VP7 amplicons in 40 μl of the second round VP7 reagent mixtures. Cycling was done with 20 cycles of the same cycling profile as the first reaction. The PCR mixtures contained 10x PCR buffer, MgCl2 (50 mM), deoxynucleoside triphosphates (10 mM), primers (10 pmol), and Taq DNA polymerase (1U). The amplified product was visualized by gel electrophoresis using 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (10 μg/mL). The 100 bp DNA ladder (GeneRuler™, Fermentas life science) was used as a molecular weight standard. Primer sequences are shown in Table 1.(25)

Table 1. Primer sequences and positions used for genotyping of VP7 gene in Rotavirus strains. (25).

| Primer | Sequence (5’→3’) | Position | Type |

| Beg9 | GGC TTT AAA AGA GAG AAT TTC CGT CTG G | nt 1-28 | - |

| End9 | GGT CAC ATC ATA CAA TTC TAA TCT AAG | nt 1062-1036 | - |

| aBT1 | CAA GTA CTC AAA TCA ATG ATG G | nt 314-335 | G1 |

| aCT2 | CAA TGA TAT TAA CAC ATT TTC TGT G | nt 411-435 | G2 |

| aET3 | CGT TTG AAG AAG TTG CAA CAG | nt 689-709 | G3 |

| aDT4 | CGT TTC TGG TGA GGA GTT G | nt 480-498 | G4 |

| aAT8 | GTC ACA CCA TTT GTA AAT TCG | nt 178-198 | G8 |

| aFT9 | CTA GAT GTA ACT ACA ACT AC | nt 757-776 | G9 |

Data analysis

Data was statistically analyzed by SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical analysis χ2 test was used to analyze the data obtained to the age group, sex, G types and seasonal distribution of the group A Rotavirus and also type of feeding. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze the clinical symptoms. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Rotavirus detection

A total of 48 (34.78%) diarrheic fecal specimens were confirmed as Rotavirus positive using EIA assay.

Rotavirus and demographic data

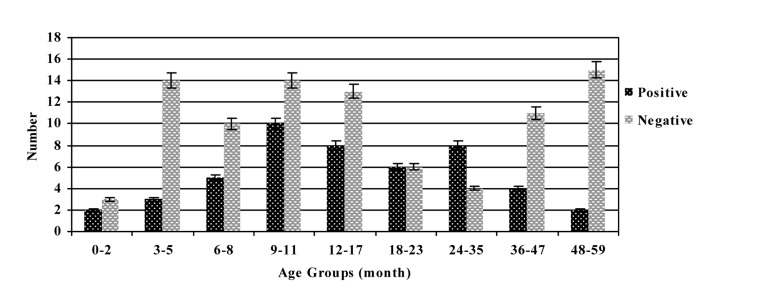

More males (68.75%) were infected than females (31.25%), and the male-to-female ratio of Rotavirus infection was 2.2:1 (P= 0.026). The age of infected children ranged from 1 to 59 months (Figure 1), and the median age was 7.9 months. Children less than 24 months of age accounted for 70.83% of the overall Rotavirus-positive cases with those between 9 and 11 months of age being the most affected (P= 0.052). The survey of clinical symptoms in Rotavirus gastroenteritis cases showed that children with infection had diarrhea (97.92%), vomiting (77.08%), fever (52.08%) and convulsion (6.25%). Also there was a relationship between Rotavirus infection diarrhea (P= 0.001) and convulsion (P= 0.049) symptoms. According to the season distribution, the highest prevalence of infection was identified in autumn (45.83%), followed by winter (33.34%),

Figure 1. Age distribution of human Rotaviruses from December 2007 to November 2008.

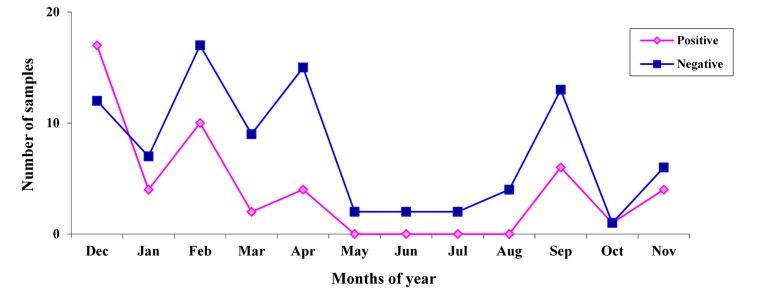

Summer (12.50%) and spring (8.33%), respectively (P= 0.012). Rotavirus was detected continuously in the 8-month period lasting from September to April. Rotavirus was detected most frequently in December–February. The presence of Rotavirus remained low in May–August in which no G type was detected (P= 0.199) (Figure 2). Overall, 62.50 % of the children with acute gastroenteritis were not breastfed and 37.50 % were breastfeeding at the time of presentation of Rotavirus infection (P= 0.236).

Figure 2. Monthly distribution of human Rotaviruses from December 2007 to November 2008.

Rotavirus genotyping

Genotyping was performed on 48 Rotavirus positive stool samples by using Nested RT-PCR (Figure 3). The most common circulating G type in the population under surveillance was mixed types, that being identified in 16 strains out of 48 samples (33.34%), followed by non-typeable (15/48, 31.25%), G4 (13/48, 27.08%), G1 (3/48, 6.25%) and G2 (1/48, 2.08%), respectively. The most prevalent mixed G types were G1/G4 (37.50%), G1/G8 (25%), G1/G3 (18.75%), G2/G8 (12.50%) and G3/G4 (6.25%), consecutively. The G types G3, G8 and G9 were not individually detected during the study. The most frequent detected type was mixed G types in females (53.33%) and G4 in males (33.33%) (P= 0.169). The most prevalent Rotavirus type reported was non-typeable and mixed infection (each 50%) in spring, non-typeable and G1 (each 33.33%) in summer, non-typeable and G4 in the autumn (each 36.36%) and mixed infection in the winter (50%) seasons (P= 0.049)

Discussion

Rotavirus is a significant cause of diarrhea in developed and under developed countries in children under five years of age, and it is essential to determine the circulating genotypes and their temporal and geographical variations. From 2007 to 2008, constant surveillance of Rotavirus diarrhea in Shiraz, Iran, showed a prevalence of 34.78% in children less than 5 years of age with gastroenteritis. This result is comparable to the disease burden of Rotavirus seen in other studies in Iran and different countries which has shown to be between 13 to 40% of all cases of gastroenteritis. (10,12,14,16-18) Extensive studies in different regions of the world have indicated that in temperate climates, Rotavirus infection occurs predominantly during the cooler months.(9,26,27) On the other hand, seasonal patterns in tropical climates have shown rates of Rotavirus diarrhea throughout the year with seasonal trends that are less are less pronounced.(6,9,12,20,21) This study demonstrated that there was a significant correlation between the seasonal distribution and Rotavirus-positive cases. Rotavirus gastroenteritis occurred throughout the year, with more cases occurring in the winter with a seasonal peak observed in the months of December to February. These findings are similar to those reported in countries with temperate climates such as: Iran,(15,16) China,(26) Burkina Faso,(28) and Spain.(29) Similar surveillances for prolonged time period are needed in order to ascertain accurately the seasonality associated with Rotavirus infection in the studied area. The occurrence of the group A Rotavirus was cumulatively observed in the first 24 months of life (70.83%) more than in the older age groups, as was found in previous investigations.(11,16,26,28,30) Rotavirus age distribution was related to the peak incidence of infection, decline in maternal antibodies, and immaturity of new passive immune responses. The high frequency of Rotavirus gastroenteritis in this age group highlights the need for a vaccine to offer optimal protection against acute Rotavirus infection in children <2 years old. During this study, diarrhea was the symptom most commonly reported that is associated with Rotavirus infection, followed by vomiting, fever and convulsion. These findings are in keeping with studies conducted in Iran and other countries.(10,28,30-33) In the present study, evaluation of the breastfeeding status of infants less than 12 months of age with severe diarrhea showed that Rotavirus-positive cases were infrequent among those being breastfed at the time of acute gastroenteritis. This result suggests that breastfeeding may be a protective factor against Rotavirus infection, as reported in other studies.(28,30,31) Worldwide genetic diversity of circulating Rotavirus strains is associated with the presentation of new emerging strains, causing variability in the geographical distribution of the virus. The most common circulating G type in our study was mixed types with two different Rotavirus G types. The proportion of mixed infections (33.34%) reported in this study is substantially lower than what was reported in Guinea-Bissau (59%),(34) and Iran (60%),(35) and higher than studies conducted in Ireland,(36) Indonesia,(37) Africa,(38) India,(39) with the prevalence of 28.5%, 23%, 21.4% and 21%, respectively. In the current survey, we documented the first case of G1/G3 mixed infection in Iran. This G type has been reported in young children with gastroenteritis in Mexico.(40) Some of the mixed types detected in the present investigation are similar with those identified in other studies.(10,20,38,40) The high prevalence of mixed infections may reflect the observed diversity of strains. Patients harboring multiple Rotaviruses may offer a unique environment for the re-assortment process, facilitating generation of novel Rotavirus strains and the maintenance of the observed diversity.(15,34,39) Separately, the high mixed infection with different Rotavirus strains may be explained by greater environmental contamination with Rotavirus, for example water resources, coupled with greater contact between children and the environment around them.(39) Therefore, the frequency of mixed infection of Rotaviruses and its effect on the development of Rotavirus vaccine should be thoroughly investigated. During this study, 31.25% of the evaluated samples were G untypeable that might be related to the presence of novel strains, the failure of the genotyping due to the presence of the other genes was not investigated in this survey; for example, rare G types such as G5, G6, G10, G12, and failure in RT-PCR technique.(25) Non-typeable Rotavirus strains are rarely reported in children with acute diarrhea in Iran and other countries.(15,16,19,37,41) In recent years G4 strain has been detected at relatively high frequency from Iran,(15,42) to Italy,(19) to South Korea,(32) and Brazil.(41) The present study revealed G4 type as the prevalent G type individually in 27.08% of all Rotavirus-positive cases. Numerous molecular epidemiological studies have shown that G1 is the most common circulating G type worldwide. (6,14,15,37,43) However the G1 type was observed only in 6.25% of all children with Rotavirus diarrhea. We detected the G2 type in the specimens of only 2.08% of patients with acute diarrhea, which is in contrast with studies conducted in Italy, Sierra Leone and India, which demonstrated that the G2 type is one of the most prevalent Rotavirus types.(10,19,20,44) In the current study, neither the G3 nor the G8 types were detected individually. These findings are distinct from those results observed in Sierra Leone,(10) Turkey,(13) Malawi,(21) and China,(45) where these G types have been identified as the most common types in children. In recent years there has been an increase in research of the importance of G9 type in many countries including Latin America,(12) Iran,(16) Albania,(19) Brazil,(37) Cuba,(46) and Tanzania.(47) However, the G9 type was not detected during the study. Investigations in developing and industrialized countries have demonstrated the need for new generations of Rotavirus vaccines to include G9 strains due to the increasing emergence of this type of group A Rotavirus. In conclusion this study provides information on the epidemiology and description of the Rotavirus G types circulating among Iranian children with acute diarrhea. Our results indicate that gastroenteritis caused by Rotavirus in the country is a significant health problem, particularly among children less than 2 years of age and during the cold season. These data will be useful for making an informed decision about the introduction of Rotavirus vaccine in Iran and provides a baseline data for future vaccine studies.

Footnotes

Acknowledgment: Our special thanks and appreciation go to the Islamic Azad University, Jahrom Branch, who provided executive support of this Project. We also thank the thoughtful of Mehdi Kargar and Dr. Ramin Yaghobi who assisted us in performing this project.

Author Contribution: KM carried out the design of the study, coordination and scientific consultation at Islamic Azad University of Jahrom. JT and NA participated in sampling and practical methods. All authors read and approved thefinal manuscript.

References

- 1.CDC Rotavirus Surveillance Worldwide, 2001-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(46):1255–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresse JS, Glass RI. Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(2):304–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glass RI, Bresee J, Jiang B, Parashar U, Yee E, Gentsch J. Rotavirus and rotavirus vaccines. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;582:45–54. doi: 10.1007/0-387-33026-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surendran S. Rotavirus infection: Molecular changes and pathophysiology. Exp Clin Sci J. 2008;7(62):154. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark HF, Marcello AE, Lawley D, Reilly M, Dinubile MJ. Unexpectedly high burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in very young infants. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mast TC, Chen PY, Lu KC, Hsu C, Lin HC, Liao WC, Lin DP, Chen HC, Lac C. Epidemiology and economic burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in hospitals and pediatric clinics in Taiwan, 2005-2006. Vaccine. 2010;28(17):3008–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estes MK, Kapikian AZ. Rotaviruses. In: Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields Virology. 5nd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Publishers; 2007. pp. 1917–74. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoshino Y, Kapikian AZ. 2000. Rotavirus serotypes: Classification and importance in epidemiology, immunity, and vaccine development. J Health Popul Nutr. 2000;18(1):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy K, Hubbard AE, Eisenberg JNS. Seasonality of rotavirus disease in the tropics: a systematic review, meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(6):1487–96. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jere KC, Sawyerr T, Seheri LM, Peenze I, Page NA, Geyer A, Steele AD. A first report on the characterization of rotavirus strains in Sierra Leone. J Med Virol. 2011;83(3):540–50. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Junaid SA, Umeh C, Olabode AO, Banda JM. Incidence of rotavirus infection in children with gastroenteritis attending Jos university teaching hospital, Nigeria. Virol J. 2011;8(233) doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linhares AC, Stupka JA, Ciapponi A, Bardach AE, Glujovsky D, Aruj PK, Mazzoni A, Rodriguez JA, Rearte A, Lanzieri TM, Ortega-Barria E, Colindres R. Burden and typing of rotavirus group A in Latin America and the Caribbean: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21(2):89–109. doi: 10.1002/rmv.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meral M, Bozdayı G, Ozkan S, Dalgıç B, Alp G, Ahmed K. Rotavirus prevalence in children with acute gastroenteritis and the distribution of serotypes and electropherotypes. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2011;45(1):104–12. [In Turkish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mast TC, Walter EB, Bulotsky M, Khawaja SS, Di Stefano DJ, Sandquist MK, Straus WL, Staat MA. Burden of childhood rotavirus disease on health systems in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(2):19–25. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ca7e2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kargar M, Akbarizadeh AR. Prevalence and molecular genotyping of group A rotaviruses in Iranian children. Indian J Virol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s13337-012-0070-7. [In Press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kargar M, Najafi A, Zandi K, Hashemizadeh Z. Genotypic distribution of rotavirus strains causing severe gastroenteritis in children under 5 years old in Borazjan, Iran. African J Microbiol Res. 2011;5(19):2936–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadeghian A, Hamedi A, Sadeghian M, Sadeghian H. Incidence of rotavirus diarrhea in children under 6 years referred to the pediatric emergency and clinic of Ghaem Hospital, Mashhad, Iran. Acta Medica Iranica. 2010;48(4):263–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaraei-Mahmoodabadi B, Kargar M, Tabatabaei H, Saedegipour S, Ghaemi A, Nategh R. Determination of annual incidence, age specific incidence rate and risk of rotavirus gastroenteritis among children in Iran. Iranian J Virol. 2009;3(1):39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Annarita P, Grassi T, Donia D, De Donno A, Idolo A, Alfio C, Alessandri C, Alberto S, Divizia M. Detection and molecular characterization of human rotaviruses isolated in Italy and Albania. J Med Virol. 2010;82(3):510–18. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatte VS, Gentsch JR, Chitambar SD. Characterization of group A rotavirus infections in adolescents and adults from Pune, India: 1993-1996 and 2004-2007. J Med Virol. 2010;82(3):519–27. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunliffe NA, Ngwira BM, Dove W, Thindwa BDM, Turner AM, Broadhead RL, Molyneux ME, Hart CA. Epidemiology of rotavirus infection in children in Blantyre, Malawi, 1997-2007. J Infect Dis. 2010;202 Suppl:S168–74. doi: 10.1086/653577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuccotti G, Meneghin F, Dilillo D, Romanò L, Bottone R, Mantegazza C, Giacchino R, Roberto Besana R, Ricciardi G, Sterpa A, Altamura N, Andreotti M, Montrasio G, Macchi L, Anna Pavan A, Paladini S, Zanetti A, Radaelli G. Epidemiological and clinical features of rotavirus among children younger than 5 years of age hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis in Northern Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:218. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le VP, Kim JY, Cho SL, Nam SW, Lim I, Lee HJ, Kim K, Chung SI, Song W, Lee KM, Rhee MS, Lee JS, Kim W. Detection of unusual rotavirus genotypes G8P[8] and G12P[6] in South Korea. J Med Virol. 2008;80(1):175–82. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahman M, Matthijnssens J, Nahar S, Podder G, Sack DA, Azim T, Van Ranst M. Characterization of a novel P[25], G11 human group a rotavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(7):3208–12. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3208-3212.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization, Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biological. Manual of rotavirus detection and characterization methods. CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland. 2008 This publication is available on the Internet at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2008/WHO_IVB_08.17_eng.pdf.

- 26.Zeng M, Chen J, Gong ST, Xu XH, Zhu CM, Zhu QR. Epidemiological surveillance of norovirus and rotavirus diarrhea among outpatient children in five metropolitan cities. Chinese J Pediatr. 2010;48(8):564–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook SM, Glass RI, LeBaron CW, Ho MS. Global seasonality of rotavirus infections. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68(2):171–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonkoungou IJO, Sanou I, Bon F, Benon B, Coulibaly SO, Haukka K, Traoré AS, Barro N. Epidemiology of rotavirus infection among young children with acute diarrhoea in Burkina Faso. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.López-de-Andrés A, Jiménez-García R, Carrasco-Garrido P, Alvaro-Meca A, Galarza PG, de Miguel AG. Hospitalizations associated with rotavirus gastroenteritis in Spain, 2001-2005. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Modarres S, Modarres S, Nassiri Oskoii N. Rotavirus infection in infants and young children with acute gastroenteritis in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health J. 1995;1(2):210–14. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gimenez-Sanchez F, Delgado-Rubio A, Martinon-Torres F, Bernaola-Iturbe E, Rota score Research Group Multicenter prospective study analyzing the role of rotavirus on acute gastroenteritis in Spain. Acta Paediatrica. 2010;99(5):738–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shim SY, Jung YC, Le VP, Son DW, Ryoo E, Shim JO, Lim I, Kim W. Genetic variation of G4P[6] rotaviruses: evidence for novel strains circulating between the hospital and community. J Med Virol. 2010;82(4):700–706. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kargar M, Najafi A, Zandi K, Barazesh A. Frequency and demographic study of Rotavirus acute gastroenteritis in hospitalized children of Borazjan city during 2008-2009. J Shaheed Sadoughi Univ Med Sci. 2011;19(1):94–103. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer TK, Page NA, Griffin DD, Eugen-Olsen J, Pedersen AG, Valentiner-Branth P, Mølbak K, Sommerfelt H, Nielsen NM. Characterization of incompletely typed rotavirus strains from Guinea-Bissau: identification of G8 and G9 types and a high frequency of mixed infections. Virol. 2003;311(1):125–33. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kargar M, Zare M, Najafi A. High prevalence of mixed rotavirus infections in children hospitalized in Marvdasht Motahary hospital, Iran during 2007-2008. Iranian J Pediatr. 2012;22(1):60–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reidy N, O'Halloran F, Fanning S, Cryan B, O'Shea H. Emergence of G3 and G9 rotavirus and increased incidence of mixed infections in the southern region of Ireland 2001-2004. J Med Virol. 2005;77(4):571–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radji M, Putman SD, Malik A, Husrima R, Listyaningsih E. Molecular characterization of human group A rotavirus from stool samples in young children with diarrhea in Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41(2):341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esona MD, Steele D, Kerin T, Armah G, Peenze I, Geyer A, Page N, Nyangao J, Agbaya VA, Trabelsi A, Tsion B, Aminu M, Sebunya T, Dewar J, Glass R, Gentsch J. Determination of the G and P types of previously nontypeable rotavirus strains from the African Rotavirus Network, 1996-2004: Identification of unusual G types. J Infect Dis. 2010;202 Suppl:S49–54. doi: 10.1086/653552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jain V, Das BK, Bhan MK, Glass RI, Gentsch JR, Indian Strain Surveillance Collaborating Laboratories Great diversity of group A rotavirus strains and high prevalence of mixed rotavirus infections in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(10):3524–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3524-3529.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodríguez Castillo A, Villa AV, Ramírez González JE, Mayén Pimentel E, Melo Munguía M, Díaz De Jesús B, Olivera Díaz H, García Lozano H. VP4 and VP7 Genotyping by Reverse Transcription-PCR of Human Rotavirus in Mexican Children with Acute Diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(10):3876–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3876-3878.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santos JS, Alfieri AF, Leite JPG, Skraba I, Alfieri AA. Molecular epidemiology of the human group A rotavirus in the Paraná State, Brazil. Braz arch biol technol. 2008;51(2):287–94. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132008000200008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanaie M, Radpour H, Esteghamati A, Keshtcar A, Nasiri M, Noochi Z, Mohebi SR, Derakhshan F, Zali MR. Prevalence and molecular characterization of rotaviruses from children with acute diarrhea in Tabriz. J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2009;13(50):69–77. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khalili B, Cuevas LE, Reisi N, Dove W, Cunliffe NA, Hart CA. Epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhoea in Iranian children. J Med Virol. 2004;73(2):309–12. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finamore E, Vitiello M, Kampanaraki A, Rao M, Galdiero M, Galdiero E, Bevilacqua P, Gallo MA, Galdiero M. G2 as an emerging rotavirus strain in pediatric gastroenteritis in southern Italy. Infect. 2011;39(2):113–9. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0102-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang YH, Kobayashi N, Zhou X, Nagashima S, Zhu ZR, Peng JS, Liu MQ, Hu Q, Zhou DJ, Watanabe S, Ishino M. Phylogenetic analysis of rotaviruses with predominant G3 and emerging G9 genotypes from adults and children in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2009;81(2):382–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ribas MA, Nagashima S, Calzado A, Acosta G, Tejero Y, Cordero Y, Daynelid Piedra D, Kobayashi N. Emergence of G9 as a predominant genotype of human rotaviruses in Cuba. J Med Virol. 2011;83(4):738–44. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moyo SJ, Gro N, Kirsti V, Matee MI, Kitundu J, Maselle SY, Langeland N, Myrmel H. Prevalence of enteropathogenic viruses and molecular characterization of group A rotavirus among children with diarrhea in Dar es Salaam Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:359. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]