Abstract

Background

Itch is the cardinal symptom of atopic dermatitis (AD). Beta-endorphin, a neuropeptide, is increased in both AD skin and sera. IL-31, an itch-relevant cytokine, activates IL-31 receptors in keratinocytes. However, how IL-31 and beta-endorphin interact in AD skin remains elusive.

Objectives

This study investigated the mechanistic interaction of IL-31 and beta-endorphin in AD.

Methods

This is a prospective cross sectional study. We recruited adult patients of AD and controls according to Hanifin's AD criteria. Serum levels of IL-31 and beta-endorphin were measured by ELISA. Expressions of IL-31RA and beta-endorphin in the skin were accessed by immunohistochemistry. Their expressions in the skin and blood were compared and correlated in AD patients and in controls. We also treated primary keratinocytes with IL-31 and measured calcium influx, beta-endorphin production, and signaling pathways to define their mechanistic interactions.

Results

We found beta-endorphin to be increased in supernatant from IL-31-treated keratinocytes. IL-31 receptor activation resulted in calcium influx and STAT3 activation; pretreatment with STAT3 inhibitor stopped the increase of beta-endorphin. Notably, either replacement of extracellular calcium or treatment with 2-APB, an inhibitor for the store-operated channel, blocked STAT3 activation. We found higher levels of blood beta-endorphin and IL-31, that are significantly correlated, in AD patients. Moreover, IL-31RA and beta-endorphin was increased and colocalized both in AD human skin and TPA-painted mouse skin.

Conclusions

We concluded IL-31R activation in keratinocytes induced calcium influx and STAT3-dependent production of beta-endorphin. These results might contribute to an understanding of regulatory mechanisms underlying peripheral itch.

Keywords: atopic dermatitis, calcium, beta-endorphin, IL-31, itch

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD), a common chronic inflammatory skin disease prevalent in 6-9% of the general population, is increasing globally 1. It is characterized by severe itch and is usually associated with a personal or family history of atopic diseases. The itch affects physical growth, mental development, emotional equanimity, and performance at school and work 2. The predominance of itch in AD patients makes it ideal to study pathophysiolgy of pruritus-like itches. Antihistamines have little effect on alleviating AD itch, suggesting histamine is not a major mediator of AD itch 3-4. Neuropeptides, proteinases, arachidonic derivates and cytokines may contribute to AD pruritus 3,5. Opioids such as morphine may induce severe itching 6. The incidence of pruritus has been reported to be 10-50% in people who have been administered opioids intravenously 7-8 and 20-100% neuraxially. Interestingly, naloxone, an antidote for morphine, suppresses itch in patients with chronic renal failure and AD 9.

Blood levels of beta-endorphin, which binds to opioid receptors, has been associated with intensity of subjective itch in AD patients 2. Beta-endorphin and its receptors are both present in keratinocytes and free nerve endings 10. Increases in endorphin are also inhibited in AD patients treated with Psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) 10. Furthermore, the cytokine IL-1 and UVR, both known to accentuate itch in AD, enhances the release of beta-endorphin from keratinocytes 11-12. Although the peripheral role of endorphins on induction of itch through the peripheral mu-opioid receptor has not been verified in the literature, indirect evidence suggests that beta-endorphin might be closely associated with itch in AD.

Cytokines are considered an important mediator in AD, but little is known about how cytokines in AD contribute to the production of peripheral beta-endorphin in AD skin. The transgenic overexpression of the cytokine IL-31 in lymphocytes in mice induces severe pruritus and dermatitis 13. It is expressed preferentially by Th2 cells, and it activates a heterodimeric receptor composed of IL-31 receptor A (IL-31RA) and oncostatin M receptor (OSMR), both found on epithelial cells and keratinocytes 13-14. The epidermis of AD patients has an increased expression IL-31R and IL-31 15,16. IL-31 can induce the production of several proinflammatory mediators, including EGF, VEGF and MCP-1, in bronchial alveolar cells 17. Blood IL-31 has been correlated to disease severity in AD patients 18. Though both IL-31 and opioid pathways are enhanced in AD skin, no study has investigated their relationship in AD. To do this, we performed an in vitro study in which we added various doses of IL-31 into primary keratinocytes of normal foreskins and measured the release of endorphins by ELISA and the expression of STAT 3, ERK, and JNK by western blot. We also performed two in vivo studies, one to measure blood level of IL-31 and beta-endorphin from patients with AD recruited from a dermatological clinic in a tertiary center and normal controls and the other study was to measure the co-localization of IL-31R and beta-endorphin in skin samples from the study group and normal controls. In addition, we measured the co-localization of IL-31R and beta-endorphin in the skin of TPA-painted mice, a model for irritant contact dermatitis. The results of this study might further advance our understanding of the regulatory mechanisms underlying peripheral itch in AD.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

IL-31 was purchased from R&D (Minneapolis, MN), and ATP and thapsigargin from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 2-APB was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). ELISA kits for endorphin, cGRP, and substance P from Bachem Corp (Torrance, CA) and were assayed following manufacturer's instructions for their levels in conditioned media from IL-31-treated keratinocytes (sensitivity at 0.5 ng/ml). Dr. Tohru Yoshioka provided Fluo-4 for the calcium propagation experiments. Antibodies for STAT3, ERK, and JNK used in Western blotting were from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA). STAT3 inhibitor S31-201 or NSC 74859 was obtained from Santa Cruz (CA), ERK inhibitor (U0126) was from Promega (Madison, WI), MAPK p38 inhibitor (Indole-5-carboxamide) from Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ).

Flow cytometry and immuno-fluorescent staining of IL-31 receptors

Human keratinocytes were obtained from adult foreskins through routine circumcisions. The method for keratinocyte cultivation is was described in a previous report 19. Keratinocytes at the third passage were then grown in keratinocyte-SFM medium free of supplements 24 h before experiments. For IL-31RA measurements, keratinocytes were stained with 1:100 mouse anti-IL-31RA (R&D Minneapolis, MN) for 30 minutes followed by FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (R&D Minneapolis, MN). We also stained keratinocytes with PE-conjugated antibody for OSMR or its corresponding isotype antibody (both E-Bioscience San Diego, CA). Flow cytometry was performed with a FACScan (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Keratinocytes were stained with the same antibodies for immunoflurescence (1:500) and examined by fluorescent microscope (Cell R, Olympus, Japan).

Immunofluorescence for beta-endorphin and IL-31RA in skin

Immunofluorescent studies for beta-endorphin were performed on 5μm serial tissue sections described previously 19. Briefly, all the sections were blocked by 10% goat sera or 3% BSA at room temperature for two hours. For single staining, the sections were incubated with rabbit anti-human beta-endorphin (1:200, Millipore, Billerica, MA) followed by goat anti-rabbit-Alexa488 (1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For double staining, cryostat sections were stained with goat anti-human IL-31R antibody and stored at 4°C overnight (1:500, R & D, MN). The next day we incubated the cryostat sections with rabbit anti-goat-IgG-FITC (1:1000, Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 1 hour at room temperature. They were also incubated with rabbit anti-human beta-endorphin (1:200, Millipore, Billerica, MA) followed by goat anti-rabbit-Alexa568 (1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Image analysis was performed by NIH imageJ. Fluorescent intensity index (0-255) was calculated in 5 random mid power fields above the dermoepidermal junction. A plugin of colocalization was used and estimated by coefficient of Spearman's correlation (−1 to 1).

Measurement of IL-31RA and beta-endorphin expressions in TPA-painted mice

To determine the co-localization of IL-31RA and beta-endorphin in the inflammatory mouse skin, we measured their co-localizations in the skin of TPA-painted mice, a model for irritant contact dermatitis. TPA painting to induce skin inflammation was adopted from our previous study20. TPA or acetone as solvent control was given four times to each animal at an interval of 24 h (8.1 nmol in 100 μl acetone; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). The mouse skin was obtained 1 h after the fourth application of TPA or acetone. Cryostat sections were stained with goat anti-mouse IL-31R antibody and stored at 4°C overnight (1:500, R & D, MN). The next day we incubated the sections with rabbit anti-goat-IgG-FITC (1:1000, Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 1 hour at room temperature. They were also incubated with rabbit anti-mouse beta-endorphin (1:200, Millipore, Billerica, MA) followed by goat anti-rabbit-Alexa568 (1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Western blotting

Methods for western blotting are described previously 19. An enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) was used to detect specific proteins. The visualized films were recorded on a digital imaging system (Alpha Imager 2000, Alpha Innotech Corp., San Leandro, CA).

Real time PCR

The RNA was extracted and assessed for purity by A260/A280 absorption. Only samples with ratios over 1.7 were used for further amplification. A 1ul sample of the products underwent real-time PCR amplification using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (ROX) (Roche Applied Science, Germany) to measure proopiomelanocortin (POMC), a precursor of beta-endorphin, according to manufacturer instructions. The primer for POMC forward, CTACGGCGGTTTCATGACCT; reverse, CCCTCACTCGCCCTTCTTG; 18SrRNA: forward, TTCGGAACTGAGGCCATGAT; reverse, TTTCGCTCTGGTCCGTCTTG. Reactions were performed using Sybr Green PCR Master Mix, and the data were collected by an ABI Prism 7700 and analyzed using a Sequence Detector 1.9.1 (ABI, CA).

Calcium propagation

Human keratinocytes were incubated with 2.5 uM Fluo-4 (a calcium sensitive dye) 20 minutes at 37°C, and then incubated with basal salt solution for 1 minute at 37°C. We measured the intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in individual live cells sequentially using Cell-R microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) attached to image analysis software. IL-31 (200 nM), ATP (1uM), or IL-8 (500ng/ml) was added as indicated.

Collection of blood from patients with AD

The patients with AD were recruited from a dermatological clinic in a tertiary center from 2008 to 2009. AD was defined based on diagnostic criteria by Hanifin and Rajka21. To be included, the patients could not have received any topical treatments for at least two weeks or any systemic treatment for two months before the study. They were excluded if their disease was considered acute, or if they had a history of diabetes, cancer, or HIV. Eighty-one of the patients with AD (40 men and 35 women, age 32.2 ± 9.4 years, range 1-71 years) were enrolled. A dermatologist took a medical history and generally surveyed the skin of each patient with AD and each normal control for skin lesions. Extrinsic AD was defined when the blood IgE level was 100 IU/ml or above, while intrinsic AD was defined when the blood IgE level was below 100 IU/ml. Venous peripheral blood was collected from all patients and controls. After centrifugation, the serum was stored at –70°C until assayed for β-endorphin and IL-31. The protocol for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. All clinical assessments and specimen collections were conducted according to principles stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Determination of serum β-endorphin by RIA and IL-31 by ELISA

The concentration of β-endorphin in sera was determined by radioimmunoassay (RIA) with the use of the 125I-RIA kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., USA) as previously described 2. The concentration of IL-31 was measured using a commercial ELISA kit (R&D, Minneapolis, MN). Although no sensitivity data was provided in the product instructions, the detection limit was about 50 pg/ml based on our standard curves.

Statistical Analysis

P-values were two-tailed and considered significant at 0.05 without adjusting by multiple testing. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's post hoc test was used for comparisons of beta-endorphin, IL-31, SCORAD index, and IgE levels between patients with extrinsic AD, intrinsic AD, and controls. It was also used for the comparisons of beta-endorphin level and POMR expressions between different IL-31 treated groups at different chronological points. The difference of fluorescent intensity of IL-31RA and beta-endorphin of skin from AD and normal controls was compared by Mann-Whitney test. Spearman's correlation test was used to exam the association between blood β-endorphin and blood IL-31 as well as the colocalization of IL-31RA and endorphin in skin. All statistical operations were performed using SAS version 8.01 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

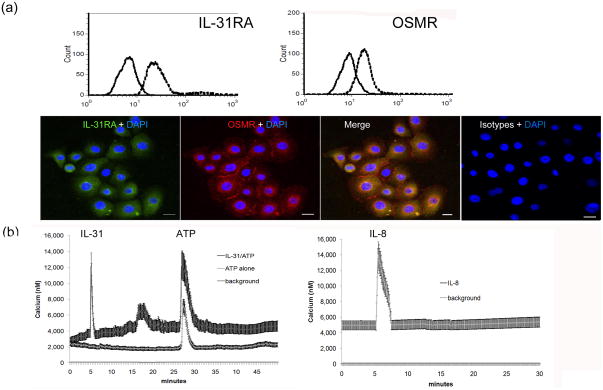

Activation of IL-31 receptors in cultured keratinocytes induced calcium propagation

To measure the expression of IL-31RA and oncostatin M receptor (OSMR) in keratinocytes in vitro, we harvested primary human keratinocytes and measured the IL-31 receptor expression by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence. IL-31RA and OSMR were both increased in the cultured keratinocytes (Figure 1A). To ensure that the receptor was functional, we measured calcium propagation in IL-31-treated keratinocytes, and first found a marked increase in calcium influx after treatment with IL-31 treatment followed by a second smaller increase in calcium five minutes later (Figure 1B). The second increase suggests other membrane channels, including space operation channels (SOC), mediating calcium influx of calcium. Moreover, IL-8, which binds to CXCR8 in keratinocytes, also induces the propagation of calcium to a similar extent.

Fig. 1.

Expression of functional IL-31 receptors in primary keratinocytes. (a) Expression of IL-31RA and oncostatin receptor (OSMR) in primary keratinocytes. The solid line represents isotype control staining while the dashed line area shows IL-31R-FITC or OSMR-PE staining in flow cytometry (upper panel). Corresponding results from immuno-fluroscence exam are shown (lower panel, bar=5 um). (b) Live cultured keratinocytes were pre-loaded with Fluo-4® to visualize calcium propagation in real time under Cell-R microscopy (Olympus). Keratinocytes were treated with IL-31 at 500 ng/ml, ATP at 1uM, and IL-8 at 500 ng/ml at the indicated time in x-axis. Y-axis shows the average optical intensity with standard deviations from a preselected group of keratinocytes and a preselected group of baseline backgrounds. Three independent experiments were performed with consistent results.

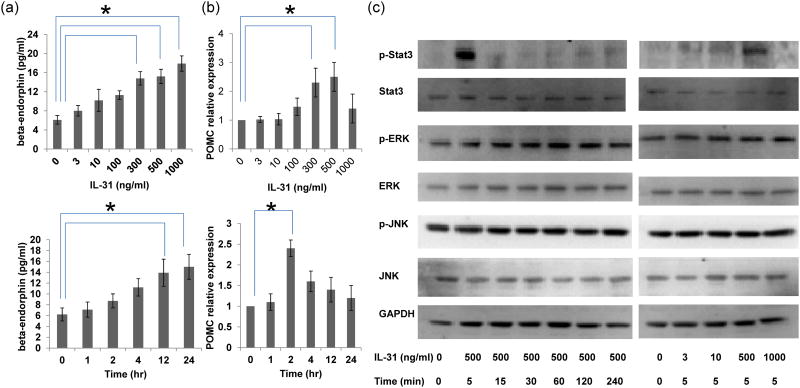

IL-31 enhanced the release of beta-endorphin but not CGRP or substance P from keratinocytes

We investigated whether IL-31 would induce the production of certain neuropeptides, including beta-endorphin, CGRP, and substance P through epidermal keratinocytes. Keratinocytes were treated with IL-31, and the release of beta-endorphin, substance P and CGRP was measured by ELISA 24 hours later. Only beta-endorphin was increased (Figure 2A). IL-31 300, 500, and 1000 ng/ml caused a two- to three-fold increase in beta-endorphin (p=0.03, 0.03, and 0.02, respectively). We also investigated whether IL-31 would upregulate POMC, the precursor of beta-endorphin using RTPCR. 300 and 500 ng/ml IL-31 induced a two- to four-fold increase in POMC (Figure 2B, p=0.02 and p=0.01, respectively). Kinetic analysis revealed that the upregulation in POMC preceded the increase of beta-endorphin, suggesting that IL-31-induced production of endorphin involved the initial transcription of POMC.

Figure 2.

IL-31 induced POMC upregulation and beta-endorphin production, along with STAT3 activation and ERK activation. (a) Keratinocytes were incubated with IL-31 at indicated concentrations for 24 hours (upper panel). For kinetic analysis, 500 ng/ml IL-31 was added into keratinocytes for 1, 2, 4, 12, and 24 hours (lower panel). Beta endorphin was measured by ELISA and POMC expression was determined by RT-PCR normalized with beta-actin (b). (c) Activation of STAT3, ERK, and JNK were measured by western blotting. Kinetic analysis was performed with 500 ng/ml IL-31 at for 5,15, 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes. In addition, keratinocytes were incubated with IL-31 at indicated concentrations for 30 minutes. Three independent experiments were performed with consistent results. * denotes p<0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis with post hoc Dunn's test.

IL-31 triggered the activation of STAT3 and ERK but not JNK

To investigate how IL-31-induced endorphin release was triggered in keratinocytes, we treated keratinocytes with 3, 10, 500, to 1000 ng/ml of IL-31 for 5 minutes and 500 ng/ml IL-31 from 5 to 240 minutes and observed the effect on its signaling pathway by Western blot. The concentrations of IL-31used were decided based on the result that IL-31 at 500 and 1000 ng/ml had optimal effects in beta-endorphin production at 24 hours (Figure 2A). Only 500 ng/ml IL-31 markedly increased the activation of pSTAT3, which peaked at 5 minutes (Figure 2C). Only 500 ng/ml IL-31 gradually increased ERK phosphorylation starting from 15 minutes and continuing to increase up to 60 minutes, at which time it stabilized (Figure 2C). The discrepancy of the concentration of IL-31 required to induce peak STAT3 activation at 5 min (500 ng/ml) and peak beta-endorphin production at 24 hours (1000 ng/ml) might result from an even earlier activation (<5 minutes) of STAT3 by IL-31 at 1000 ng/ml or another undisclosed STAT3-independent pathway.

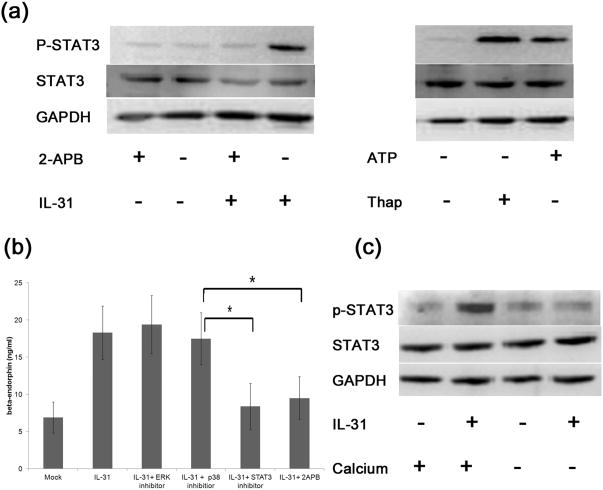

Capacitive calcium entry mediated STAT3 activation in IL-31-treated keratinocytes

We further investigated the role of capacitive calcium entry in IL-31-induced STAT3 activation. Because 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) is a blocker of store-operated Ca2+ entry 22 and thapsigargin, an inhibitor of intracellular calcium (SERCA) pumps, mediates capacitive calcium entry by emptying ER store of calcium, we used 2-APB and thapsigargin to inhibit and activate capacitive calcium entry, respectively. 2-APB blocked STAT3 activation in IL-31-treated keratinocytes (Figure 3A), while thapsigargin and ATP treatment alone substantially increased STAT3 activation (Figure 3A), indicating that capacitive calcium entry mediated the STAT3 activation by IL-31. Further, replacement of culture medium with calcium free medium abrogated the activation of STAT3 (Figure 3C), suggesting that calcium entry may play a role in IL-31-mediated STAT3 activation.

Fig.3.

IL-31 induced STAT3 activation, calcium propagation, and beta-endorphin release. (a) Keratinocytes were treated with IL-31 at 500 ng/ml with or without 2-APB at 50uM for 5 minutes. STAT3 and its phosphorylation were analyzed by western blot. Keratinocytes were also treated with ATP at 1mM or thapsigargin (Thap) at 300nM for 5 minutes. Three independent experiments were performed and produced consistent findings. One set representative data is shown. (b) Keratinocytes were treated with IL-31 at 500 ng/ml for 24 hours with or without pretreatment of a p38 MAPK inhibitor (30 uM), an ERK inhibitor (30uM), a STAT3 inhibitor (30uM), and a SOCs inhibitor (2-APB, 50uM) for 2 hours. Cultured supernatants were collected and assayed for beta-endorphin by ELISA. * denotes p<0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis with post hoc Dunn's test. (c) IL-31-induced-STAT3 activation depended on the presence of extracellular calcium. Keratinocytes were treated with IL-31 at 300 ng/ml for 5 minutes with regular calcium (120 nM)(Lane 2). Replacement of the regular calcium medium with calcium free medium abolished the activation of p-STAT3 (Lane 4). Three independent experiments perform and produced consistent results. One representative set of data is shown.

IL-31 increased beta-endorphin release from keratinocytes via STAT3

Having found that IL-31 induced STAT3 activation through calcium influx and that IL-31 induced beta-endorphin release, we asked whether the release of beta-endorphin was dependent on STAT3 activation. To find out, we pretreated the keratinocytes with a p38MAPK inhibitor, an ERK inhibitor, a STAT3 inhibitor, or a SOCs inhibitor, two hours before IL-31 treatment and measured the release of beta-endorphin (Figure 3B). The increase of beta-endorphin was abrogated only by STAT3 inhibition (p=0.02) or SOCs inhibition (p=0.03) by 2-APB, indicating IL-31-mediated release of beta-endorphin depended on the activation of STAT3 and influx of calcium. Considered with the previous results, this blocking test provided evidence that in keratinocytes IL-31 first induced the influx of calcium which, in turn, activated STAT3, leading to the release of beta-endorphin.

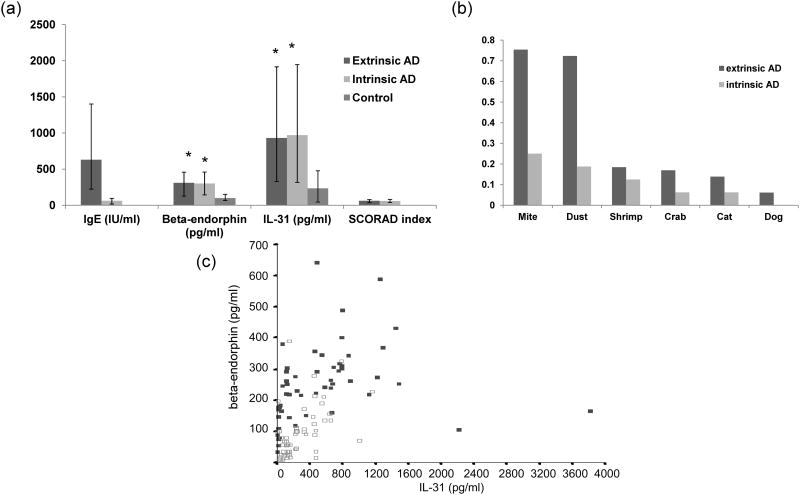

IL-31 was significantly correlated with beta-endorphin in sera from patients with AD

To further determine the biological significance of our findings and extrapolate our data in vivo, we studied the possible correlation of the blood levels of IL-31 and beta-endorphin in AD patients and controls. We recruited 81 patients with chronic AD (age 41.3 +/− 22.9) and 70 normal controls (age 38.6 +/− 20.4) from our dermatology clinic (Figure 4). Although blood IL-31 and beta-endorphin levels were higher in AD patients (p=0.02 and 0.03, respectively), they were not significantly different in extrinsic versus intrinsic AD (n=65 and 16; p=0.27 and 0.35, respectively). We did find, however, a significant association between serum beta-endorphin levels and IL-31 levels in AD patients and controls by Spearman's correlation analysis (p=0.02, r=0.82 and p=0.03, r=0.78) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

There was a significant correlation between serum beta-endorphin and IL-31. (a) Patients (n=81, including 65 extrinsic AD and 16 intrinsic AD) and controls (n=70) were defined and recruited. IL-31 and endorphin were measured in the blood, by ELISA and RIA, respectively, of both groups and compared. Values of median and lower and upper quartiles are shown.* denotes p<0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis with post hoc Dunn's test when compared with controls. (b) Percentiles of selective allergen specific IgEs from extrinsic and intrinsic AD were recorded. (c) A dot-plot graph showing beta-endorphin and IL-31 levels is shown. Closed square represents the value from patients with AD while open square represents that from normal controls. There were good correlations between IL-31 and beta-endorphin levels in both AD patients and controls.

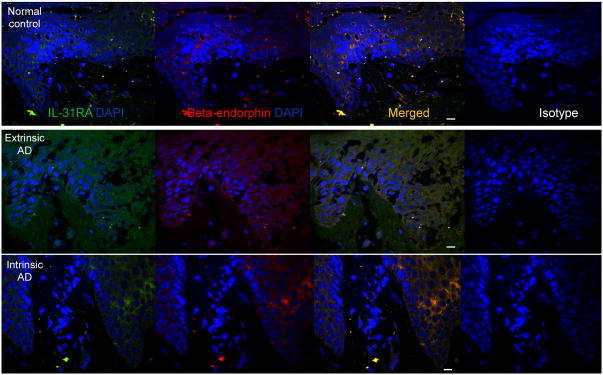

IL-31RA and endorphin were both increased and colocalized in AD skin

Having observed an increase of beta-endorphin in IL-31 keratinocytes in vitro, we wondered whether beta-endorphin and IL-31RA would be increased and colocalized in skin. We took four samples from the skin of extrinsic AD patients (19 to 52 year old), four samples from skin of intrinsic AD patients (20-55 years old), and five from the skin of normal controls (22 to 49 years old). Using immunofluorescence for IL-31RA and beta-endorphin, we found a significantly greater increase in IL-31RA in the intercellular space in epidermis from both extrinsic and intrinsic AD skin than from control skin based on fluorescent intensity indices represented as median and lower - upper quartiles: 60 (14-78) and 53 (12-79) vs. 14 (7-25)(p=0.02, Mann-Whitney test) (Figure 5). Similarly, fluorescent intensity indices indicated significantly greater increase in beta-endorphin: 75 (25-89) and 76 (27-85) vs. 16 (8-35) (p=0.03, Mann-Whitney test). Notably, IL-31RA expression and beta-endorphin expression was strongly co-localized in both AD and normal skin (extrinsic AD patients p=0.01, r=0.90, intrinsic AD patients p=0.0, r=0.89, and controls p=0.02, r=0.83, Spearman's correlation).

Figure 5.

Colocalization of beta-endorphin and IL-31RA in the human AD skin. Skin sections from patients with extrinsic AD, intrinsic AD, or normal controls (n=4, 4, and 5, respectively) were stained with antibodies for beta-endorphin and IL-31-RA or corresponding isotype antibodies. Fluorescence intensity per unit area of epidermal beta-endorphin or IL-31RA was measured in each group, and median and quartile values were calculated. There was more beta-endorphin and IL-31RA in AD skin than normal skin. Spearman's correlations are given for both type of AD patients and normal controls in terms of the colocalization for beta-endorphin and IL-31RA in skin samples. (DAPI in blue, beta-endorphin in red, and IL-31RA in green, scale bar=20μm, representative fields were shown).

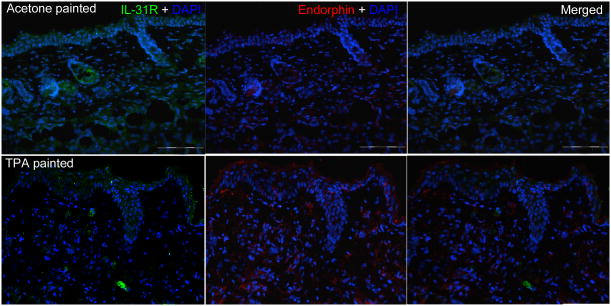

IL-31RA and beta-endorphin are increased in parallel in TPA-painted mice

Since we observed the colocalization of IL-31RA and beta-endorphin in AD skin and the correlation of IL-31 and beta-endorphin in the blood, we asked whether this association could be reproduced in mice. Balb/c mice were painted with TPA to induce skin inflammation and itch. Using immunofluorescence (Figure 6), we found a significantly greater increase in IL-31RA in the intercellular space in epidermis from TPA-treated mouse skin than from acetone-treated control skin based on fluorescent intensity indices represented as median and lower - upper quartiles: 67 (11-77) vs. 10 (5-18)( p=0.02, Mann-Whitney test). Similarly, beta-endorphin expression was also focally increased in the epidermal keratinocytes from skin painted with TPA; 32 (12-56) vs. 7 (3-15) (p=0.02, Mann-Whitney test). Among the staining, some of the beta-endorphin and IL-31RA expressions were colocalized in the epidermis.

Figure 6.

Increased expressions of beta-endorphin and IL-31RA in mouse skin painted with TPA. Skin sections from Balb/c mice were painted with TPA or acetone solvent only (n=6 and 6, respectively). The sections were stained with antibodies for beta-endorphin and IL-31-RA (DAPI in blue, beta-endorphin in red, and IL-31RA in green, scale bar= 100 μm, representative fields were shown).

Discussion

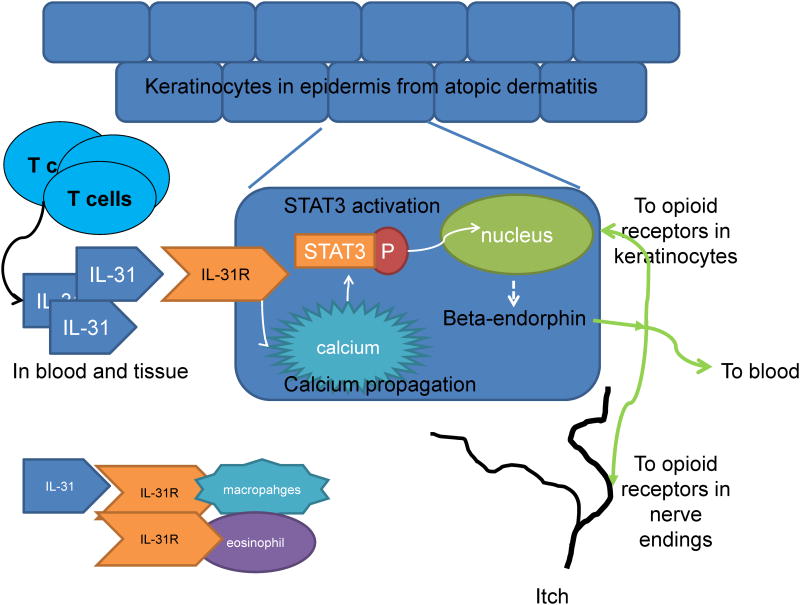

This study demonstrated that IL-31 could induce the release of beta-endorphin from keratinocytes through the entry of capacitive calcium and activation of STAT3 (Figure 7). Blood IL-31 and beta-endorphin were significantly correlated in both AD patients and normal controls. IL-31RA and beta-endorphin were increased and colocalized in AD skin.

Figure 7.

TheIL-31/STAT3/beta-endorphin axis plays a possible role in the regulation of peripheral itch in AD. IL-31, produced by activated Th cells in skin, activated IL-31R in keratinocytes, mobilized calcium and STAT3 activation, leading to the release of beta-endorphin, which might bind to u-opioid receptors in keratinocytes and free nerve endings. This axis might be important in the regulation of peripheral itch in AD.

Calcium influx follows shortly after the activation of the membrane receptor. Chemokines, for example, are reported to induce calcium entry to induced activation of eosinophils 23. The second phase of calcium propagation after IL-31 treatment in our study suggested that capacitive influx of calcium was involved in IL-31 signaling. Capacitive calcium influx is very important in cell signaling 24. In T lymphocytes, the master protein for capacitive calcium influx, STIM1, is required for the production of IL-2 and IFN-gamma 25. Studies of keratinocytes report capacitive calcium influx to be important for cell differentiation 26,27, and to be downregulated in psoriatic skin 28. In the present study, capacitive calcium influx was needed for IL-31 to induce STAT3 activation. Although the signaling pathways after IL-31 receptor activation have been reported in several cell lines from bronchial and colonic epithelium 17,29-31, this study represents the first to uncover the IL-31 signaling pathway in primary keratinocytes. More importantly, we demonstrate that keratinocyte production of beta-endorphin is mediated sequentially as follows: IL-31-calcium-STAT3-beta-endorphin. Although ERK was also activated by IL-31 in keratinocytes, blocking of ERK activation did not abrogate the release of beta-endorphin, suggesting that ERK is not directly involved in this process.

200 to 300 ng/ml of IL-31 was required to induce beta-endorphin production in vitro. Blood concentrations 1 ng/ml were hundreds of times lower than those used in vitro. Thus, the pathological significance of IL-31 in AD may be debatable. Our in vitro data in this study showed that IL-31 was produced at 3.6 ∼ 12.1 ng/ml and 2.1 ∼ 4.5 ng/ml by CD3/CD28-activated T cells from three patients with AD and three controls, respectively. Although these concentrations were still a log lower, the concentrations in the microenvironment of AD skin may not be equivalent to the in vitro concentrations of IL-31 induced by artificial activation of CD3 and CD28. The existence of certain other IL-31 releasers, such as superantigen32, might contribute to the differences in IL-31 concentrations between in vitro activation by CD3 and CD28 and AD skin in vivo. Moreover, in intestinal 29 and bronchial epithelial cells17, the IL-31 level required to activate intracellular signaling was 100 ng/ml, only one-third of 300 ng/ml. In addition, other cells might also express IL-31 and the blood level of IL-31 might not directly reflect IL-31 level in the skin microenvironment.

Keratinocytes are not the sole source of blood beta-endorphin. Blood beta-endorphin mostly comes from the pituitary gland (central) and also from adrenals, leukocytes, and epidermal keratinocytes (peripheral). Although we found a correlation between blood levels of IL-31 and beta-endorphin in AD patients, confounder(s) such as stress and related factors might also result in increase of IL-31 and beta-endorphin in AD patients. Nevertheless, the levels and correlations between IL-31 and beta-endorphin served as good biomarkers for itch in AD patients. Beta-endorphin is also released by TNF-alpha-stimulated fibroblasts 33. It can activate mast cells, leading to degranulation and immediate wheals 34. Human epidermal keratinocytes and nerve endings express functionally active micro-opiate receptors, and the keratinocytes can influence free nerve endings by secreting beta-endorphin and vice versa 35. Thus, during neurogenic inflammation, a reciprocal opioid-axis communication exists between keratinocytes and nearby nerve endings. Interestingly, there is a significant downregulation of the mu-opiate receptor in the epidermis of AD patients 36, possibly resulting from internalization of the receptor 36.

We found only endorphin but not substance P or CGRP to be upregulated by IL-31. Only few studies have investigated STAT3 activation and production of substance P, CGRP, or beta-endorphin, including one reporting a correlation, not a causal relationship, between STAT3 activation and CGRP in EPO-activated axons 37. In addition, POMC-specific STAT3 mutants diminish POMC expression, further supporting the notion that STAT3 is required for POMC transcription 38 and supporting our results showing IL-31 induced POMC upregulation.

In summary, IL-31 increases beta-endorphin in keratinocytes through capacitive calcium influx and STAT3 activation. The correlations of IL-31 and beta-endorphin in the blood and the colocalization of IL-31RA and beta-endorphin in the skin suggests the IL-31 and opioid axes might be related to pruritus in AD. These results might further our understanding of the regulatory mechanisms underlying peripheral itch in AD. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the direct role of opioids in peripheral itch in AD.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC95-2314-B-037-024, NSC96-2314-B-037-043), National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EO-096-PP-11; NHRI CN-PD-9611P), Kaohsiung Medical University (KMU)(KMU-QA096005), and KMU Center of Excellence for Environmental Medicine (98.2b). SKH is supported, in part, by NIH grants (AI-052468 and AI073610).

We would like to thank Kaohsiung Medical University for the use of their research facility and thank Dr, Katz of the National Institutes of Health for his valuable comments and input regarding this article.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared

Author contributions: CL, CH, and WY performed the experiments. HC, SH, GC contributed to discussion. TY designed the experiments and analysed the data. MS, WL, and YK analyzed the data. CL and HY designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed to discussion, wrote and edited the paper.

For more information: Author's website: http://researcher.nsc.gov.tw/zieben/en/

Patients Association: http://www.nationaleczema.org/

Protein information: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/AAI32999.1

References

- 1.Leung DY, Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2003;361:151–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee CH, Chuang HY, Shih CC, et al. Transepidermal water loss, serum IgE and beta-endorphin as important and independent biological markers for development of itch intensity in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1100–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greaves MW, Khalifa N. Itch: more than skin deep. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;135:166–72. doi: 10.1159/000080898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yosipovitch G, Greaves MW, Schmelz M. Itch. Lancet. 2003;361:690–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stander S, Steinhoff M. Pathophysiology of pruritus in atopic dermatitis: an overview. Exp Dermatol. 2002;11:12–24. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2002.110102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballantyne JC, Loach AB, Carr DB. Itching after epidural and spinal opiates. Pain. 1988;33:149–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gan TJ, Ginsberg B, Glass PS, et al. Opioid-sparing effects of a low-dose infusion of naloxone in patient-administered morphine sulfate. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1075–81. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199711000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodhouse A, Hobbes AF, Mather LE, et al. A comparison of morphine, pethidine and fentanyl in the postsurgical patient-controlled analgesia environment. Pain. 1996;64:115–21. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cousins MJ, Mather LE. Intrathecal and epidural administration of opioids. Anesthesiology. 1984;61:276–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tominaga M, Ogawa H, Takamori K. Possible roles of epidermal opioid systems in pruritus of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2228–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanello SB, Jackson DM, Holick MF. An immunocytochemical approach to the study of beta-endorphin production in human keratinocytes using confocal microscopy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;885:85–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wintzen M, Yaar M, Burbach JP, et al. Proopiomelanocortin gene product regulation in keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:673–8. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12345496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillon SR, Sprecher C, Hammond A, et al. Interleukin 31, a cytokine produced by activated T cells, induces dermatitis in mice. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:752–60. doi: 10.1038/ni1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diveu C, Lak-Hal AH, Froger J, et al. Predominant expression of the long isoform of GP130-like (GPL) receptor is required for interleukin-31 signaling. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2004;15:291–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilsborough J, Leung DY, Maurer M, et al. IL-31 is associated with cutaneous lymphocyte antigen-positive skin homing T cells in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neis MM, Peters B, Dreuw A, et al. Enhanced expression levels of IL-31 correlate with IL-4 and IL-13 in atopic and allergic contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:930–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ip WK, Wong CK, Li ML, et al. Interleukin-31 induces cytokine and chemokine production from human bronchial epithelial cells through activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathways: implications for the allergic response. Immunology. 2007;122:532–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raap U, Wichmann K, Bruder M, et al. Correlation of IL-31 serum levels with severity of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:421–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CH, Chen JS, Sun YL, et al. Defective beta1-integrins expression in arsenical keratosis and arsenic-treated cultured human keratinocytes. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:129–38. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan J, Nakade K, Huang YC, et al. Suppression of cell-cycle progression by Jun dimerization protein-2 (JDP2) involves downregulation of cyclin-A2. Oncogene. 2010;29:6245–56. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanifin J, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatol Venereol (Stockh) 1980;92:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bootman MD, Collins TJ, Mackenzie L, et al. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) is a reliable blocker of store-operated Ca2+ entry but an inconsistent inhibitor of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release. FASEB J. 2002;16:1145–50. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0037rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsner J, Petering H, Kimmig D, et al. The CC chemokine receptor antagonist met-RANTES inhibits eosinophil effector functions. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999;118:462–5. doi: 10.1159/000024164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prakriya M, Feske S, Gwack Y, et al. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–3. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh-Hora M, Yamashita M, Hogan PG, et al. Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:432–43. doi: 10.1038/ni1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bikle DD, Ratnam A, Mauro T, et al. Changes in calcium responsiveness and handling during keratinocyte differentiation. Potential role of the calcium receptor. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1085–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI118501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fatherazi S, Belton CM, Izutsu KT. Sequential activation of store-operated currents in human gingival keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:120–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karvonen SL, Korkiamaki T, Yla-Outinen H, et al. Psoriasis and altered calcium metabolism: downregulated capacitative calcium influx and defective calcium-mediated cell signaling in cultured psoriatic keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:693–700. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dambacher J, Beigel F, Seiderer J, et al. Interleukin 31 mediates MAP kinase and STAT1/3 activation in intestinal epithelial cells and its expression is upregulated in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2007;56:1257–65. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.118679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perrigoue JG, Li J, Zaph C, et al. IL-31-IL-31R interactions negatively regulate type 2 inflammation in the lung. J Exp Med. 2007;204:481–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jawa RS, Chattopadhyay S, Tracy E, et al. Regulated expression of the IL-31 receptor in bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells, pulmonary fibroblasts, and pulmonary macrophages. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2008;28:207–19. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonkoly E, Muller A, Lauerma AI, et al. IL-31: a new link between T cells and pruritus in atopic skin inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:411–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teofoli P, Frezzolini A, Puddu P, et al. The role of proopiomelanocortin-derived peptides in skin fibroblast and mast cell functions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;885:268–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casale TB, Bowman S, Kaliner M. Induction of human cutaneous mast cell degranulation by opiates and endogenous opioid peptides: evidence for opiate and nonopiate receptor participation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984;73:775–81. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(84)90447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bigliardi-Qi M, Sumanovski LT, Buchner S, et al. Mu-opiate receptor and Beta-endorphin expression in nerve endings and keratinocytes in human skin. Dermatology. 2004;209:183–9. doi: 10.1159/000079887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bigliardi-Qi M, Lipp B, Sumanovski LT, et al. Changes of epidermal mu-opiate receptor expression and nerve endings in chronic atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 2005;210:91–9. doi: 10.1159/000082563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toth C, Martinez JA, Liu WQ, et al. Local erythropoietin signaling enhances regeneration in peripheral axons. Neuroscience. 2008;154:767–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu AW, Ste-Marie L, Kaelin CB, et al. Inactivation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in proopiomelanocortin (Pomc) neurons causes decreased pomc expression, mild obesity, and defects in compensatory refeeding. Endocrinology. 2007;148:72–80. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]