Abstract

Time is a vehicle that can be used to represent aging-related processes and to index the amount of aging-related resources or burdens individuals have accumulated. Using data on cognitive (memory) performance from two Swedish studies of the elderly (OCTO and OCTO-TWIN), we illustrate how time-as-process and time-as-resources/burdens time metrics can be articulated and incorporated within a growth curve modeling framework. Our results highlight the possibilities for representing the contributions of primary, secondary, and tertiary aspects of aging to late-life changes in cognitive and other domains of functioning.

Keywords: longitudinal, development, aging, disability, mortality, growth modeling

One of the primary objectives of lifespan developmental research is to describe intraindividual changes across time (Baltes & Nesselroade, 1979; Wohlwill, 1973). Time is often indexed as chronological age. But, what is time? K. Warner Schaie (1965), among others, recognized early on that development was driven by a multitude of processes and constructs (e.g., age, period, cohort) and illustrated through his general developmental model that time can be characterized in different ways and indexed in relation to different starting or ending points.

Conceptually, the metric on which time is indexed can be considered a vehicle (variable) representing and condensing a particular set of processes (Wohlwill, 1973). Thus, depending on the sets of processes or constructs one is interested in, different time metrics may be of use. For instance, Sliwinski, Hofer, Hall, Buschke, and Lipton (2003) illustrated how different developmental processes might be invoked via time since birth (age), time since dementia diagnosis, time to dropout, or time to death. Describing how differences and changes are organized in relation to these and other types of time may reveal additional insights into when and how aging proceeds (Li & Schmiedek, 2002). Following and expanding Sliwinski et al.’s lead, we illustrate two ways in which age-related, pathology-related, and mortality-related aspects of aging can be articulated and invoked within the context of contemporary growth curve methodology. As will be elaborated, time can be incorporated in the growth curve model at both within-person and between-person levels of analysis – as proxy for process and as proxy for personal resources/burdens, respectively. Together, the process and resources/burdens time metrics are used to articulate and test hypotheses regarding how late-life development is driven by multiple time-related processes.

Aging, Time, and Growth Modeling

The lifespan and gerontological literatures propose that trajectories of behavioral change at the end of life reflect a combination of age-related, pathology-related, and mortality-related processes. For example, Birren and Cunningham (1985; see also Busse, 1969) highlighted conceptual distinctions between primary, secondary, and tertiary aspects of aging. Primary or normal aging refers to the typical changes that most people experience with increasing age – processes thought to accrue with age and are causally linked to age-related biological and physical deterioration. Secondary or pathological aging encompasses changes that accrue with or are causally linked to disease and disability. Tertiary or mortality-related aging refers to accelerated functional deteriorations that manifest shortly (months, maybe years) before death. By definition, these tertiary changes are not so much correlated with age, but with impending death.

In recent years, longitudinal studies of growth and change have been making good use of growth curve modeling methods (see Hertzog & Nesselroade, 2003; McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003; Schaie & Hofer, 2001). Repeated assessments from multiple persons are used as the raw data for analytic procedures that model interindividual differences in intraindividual change. Without going into detail here (see methods section), a simple linear growth model can be written in two parts/levels – a within-person model and a between-person model. At the within-person level, the model indicates how individuals’ performance or ability changes as Timeti, a time-varying predictor measured at occasion t for person i, proceeds from one measurement occasion to the next (i.e., Yti =β0i + β1iTimeti + eti). The longitudinal, within-person model invokes time as an on-going process, the specific progression of which is captured by individual-specific intercepts and slopes, β0i and β1i. The slope coefficient, β1i, specifically, indicates the amount of change in the outcome, Yti, expected for one unit increase of Time. Conceptually, the slope coefficient is an attribute of the person, indicating the contribution of underlying processes to that person’s scores. One way to think of this is that each person receives a yearly injection of process – a substance that “causes” the observed changes. At the between-person level, the size of the injection may differ across individuals. For example, one individual’s yearly injection may contain a lot of age-related process, another’s only a little. Conceptually, the cross-sectional, between-person level of the model describes how and, with the inclusion of additional predictors (e.g., SES), potentially why the process progresses in a different manner for individuals with different characteristics or levels of resources (e.g., β1i =γ10 + γ11Resourcesi + u1i) – why some individuals get larger injections than others. For example, individuals with more resources may receive relatively small injections of age-related decline. In contrast, individuals with few resources might be prone to relatively large injections of age-related decline.

Making use of the two-level structure, time can be introduced into the growth modeling framework in two ways – in a longitudinal manner (the within-person level), and in a cross-sectional manner (the between-person level).

Within-person: Time as Process

At the within-person level, time serves as a proxy for process, and based on the “type” of time index used, primary, secondary, tertiary processes may be represented.

Primary aging processes

Most aging research seeks to describe and understand systematic changes that occur as a result of primary or normative aging processes (see Alwin, Hofer, & McCammon, 2006; Hertzog & Nesselroade, 2003; Schroots & Birren, 1990). Longitudinal observations obtained over multiple individuals’ life-spans are indexed along a time-from-birth, or chronological age, time axis. Individuals’ behavior (e.g., memory performance) is tracked as they move from left to right along the time axis with chronological age acting as a time-varying indicator of progressive age-related processes.

Secondary aging processes

Biological perspectives draw a distinction between endogenous (primary) and exogenous (secondary) aspects of aging (cf. Austad, 2001) and suggest that typical age-related changes, which are intrinsic to growing older and are irreversible, be separated from disease-related changes that are, in principle, reversible or preventable. In similar fashion, prominent biopsychosocial theories, such as the Disablement Process model (Verbrugge & Jette, 1994), implicate disablement as a major force underlying developmental change. Longitudinal observations obtained over the life span can, for individuals who at some point become disabled, be indexed along a time-to/from-disability time axis that serves as a time-varying proxy for the progression of secondary or disease/disability-related processes.

Tertiary aging processes

Notions of terminal decline (Kleemeier, 1962) suggest that mortality-related processes may rise to the forefront and drive the changes occurring during the last years of life (for overviews, see Bäckman & MacDonald, 2006; Berg, 1996). Longitudinal observations are, in this case, indexed along a time-to-death time axis that serves as a time-varying proxy for tertiary aging processes.

Between-person: Time as a Resource/Burden

At the cross-sectional, between-person level time can be considered as proxy for individual resources or burdens (cf. Heirich, 1964). The general idea is that time is a fixed-sum resource that has been accumulated and/or spent. As with other types of resources (e.g., income), individuals differ in the amount of time-related resources they have available. Working now at the between-person level, time is considered as a fixed, trait-like, time-invariant, individual characteristic. For example, consider how individuals might be compared on accumulated age, or time-lived. Older individuals have more ‘time-lived’ than younger individuals. They have attained a greater amount of age-related resources (e.g. life experiences), or age-related burdens (e.g. wear and tear on their joints). In a typical examination of cross-sectional age differences, time is invoked as an interindividual differences variable and regressed on between-person differences in a construct of interest, e.g., Yi = γ0 + γ1(agei) + ui. More generally, results from such models can be used to infer how between-person differences in time, as a fixed-sum resource (or burden), are related to the outcome measure (Heirich, 1964).

Multiple aspects of time-related resources/burdens can be obtained when considering the sequence of events an individual may encounter across his or her life span. In the context of the current example, events of interest include birth, disability onset, and death. Knowledge of when in time these three events occur allows for calculation of three between-person, time-as-a-resource variables that roughly correspond to the primary, secondary, and tertiary aspects of aging.

Primary age

From both accumulation of experience and accumulation of strain perspectives, a person’s chronological age can be thought of as a variable that indicates the amount of normative age-related resources or burdens an individual has accumulated thus far.

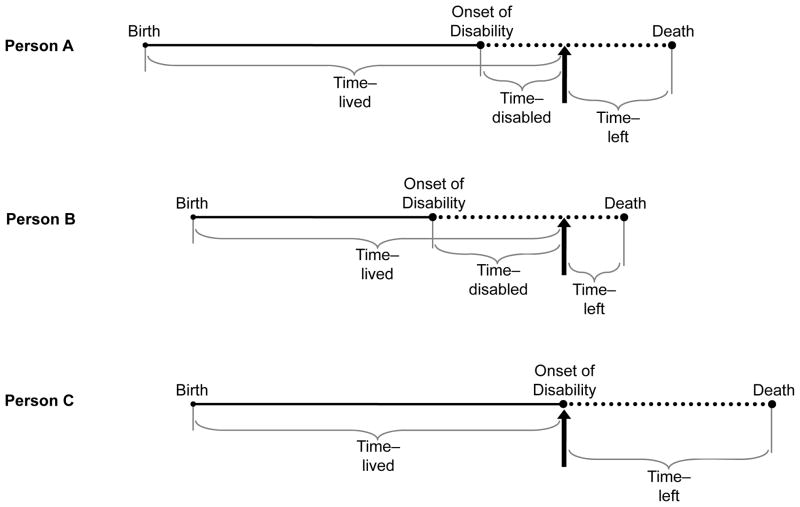

Consider the three individual life spans depicted in Figure 1. The timing of three major life events (birth, disability onset, and death) are indicated. At a given point of observation, represented by the arrow, each person has accumulated a particular number of years of life, some more, some less. For example, as indicated by the differential length of the lines to the left of the arrow, Person A has a greater amount of time-lived than does Person B. As a marker of ‘cross-sectional’ between-person differences at the point of assessment, this translates simply into Person A having accumulated more of life’s experiences (or burdens, depending on the theoretical orientation) than Person B.

Figure 1.

Three persons’ life spans with between-person similarities and differences in the timing of three major life events (birth, disability onset, and death). At a given point of observation, indicated by the arrow, each person has accumulated a particular number of years of life (time-lived), years of life lived with disability (time-disabled), and has a particular number of years of life before death (time-left).

Secondary age

A parallel construct treating time as a resource/burden can be tethered to secondary aging. Conceptually, time-disabled begins accumulating from the first onset of disability, sometimes continuously, and sometimes in spurts (e.g., as individuals recover and perhaps become disabled again). This time variable provides an indication of the total amount of secondary aging resources or burdens an individual has accumulated thus far, and is indicated in Figure 1 as the length of the lines between the point of disability onset and the point of assessment. As depicted, Person B has accumulated more time-disabled than Person A. Person C is being observed right at disability onset, and has not yet accumulated any time-disabled.

Tertiary age

Post-hoc we can also obtain a measure of individuals’ mortality-related resources/burdens. Consider the length of individuals’ entire life span. Time-lived is accumulated from birth onwards. In complement, time-left is depleted completely at the end of life. In Figure 1, the length of the line to the right of the arrow indicates how much time each person has left to spend. Person C has a greater amount of time-left than do Persons A and B. As with the complementary time-lived marker of ‘cross-sectional’ differences, time-left also invokes notions of time as either an accumulated resource or an accumulated burden, depending on theoretical orientation.

Analytically, the three time-as-resources variables, time-lived, time-disabled, and time-left, provide metrics of time on which to compare individuals to one another. Note that when time is considered as a proxy for level of personal resources or burden, it is used as an index of a single between-person (cross-sectional) differences attribute, not as a way to index the repeated observations. Such between-person differences can then be examined with respect to other differences, including between-person differences in within-person change.

Examining Aging, Disablement, and Dying: Multiple Time Metrics

Primary, secondary, and tertiary aspects of aging likely all simultaneously contribute to intraindividual changes in functionality and the interindividual differences therein (Birren & Cunningham, 1985). Multivariate combinations of the various time metrics indicating those processes should thus be considered (cf. Sliwinski et al., 2003). Following the two levels of the growth curve model, one can first determine which of the time-as-process metrics, and the different sets of processes they represent, provides the most efficient description of observed within-person changes in the outcome of interest. Second, the time-as-resources/burdens measures can be incorporated as predictors of between-person differences in change. Methodologically, this allows for integrating process (within-person) and resource (between-person) time metrics within a single growth curve model. Conceptually, it provides a description of how primary, secondary, and tertiary aging together contribute to late-life changes.

Methods

To examine how late-life changes might be organized with respect to aging, disablement, and dying (and the various time metrics used to represent those processes and burdens), we make use of data on cognitive (memory) performance obtained in two Swedish multidisciplinary population-based studies of aging: 123 randomly-selected twins from elderly twin pairs in the OCTO-TWIN study (Origins of Variance in the Old-old: Octogenarian Twins; McClearn et al., 1997) and 242 elderly individuals from the OCTO study (Aging and Development in the Oldest Old: Octogenarians; Johansson & Zarit, 1995). Detailed overviews of data collection procedures and specific measures used here can be found in the above references. In short, the studies span five waves of longitudinal data collected at approximately two-year intervals from participants aged 79 to 98 years. We make use of data collected from a total of 365 participants who (a) were disabled at one or more occasions, and (b) have since died. Select details relevant to the example are presented below.

Outcome Measure: Memory Recall

For the current illustration, we use a memory recall test where participants were asked to memorize a 10-item word list and recall those same items 30 minutes later. At their first assessment, the 365 individuals’ scores ranged from 0 to 10 (M = 4.26, SD = 3.23).

Within-person: Time as Process

Age

Chronological age is recorded at each observation point as the number of years since an individual’s birth. At the time of the first observation, participants (N = 365) were between 79 and 91 years (M = 86.07 years, SD = 2.82) of age.

Time-to/from-Disability

Disability was assessed using standard measures of basic personal activities of daily living (PADL; Katz et al., 1963). Individuals indicated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 = “completely independent” to 3 = “unable to do the activity at all” their ability to bathe, dress, toilet, and feed oneself (for reliabilities, see Zarit et al., 1993, 1995). We define the onset of disability as the date of the first interview at which it was reported that an individual could not perform one or more PADL tasks independently (i.e, any response > 0; see Guralnik et al., 2002; Seeman et al., 1996). Number of years to and from this point of onset serves as a time-to/from-disability time metric. While birth date and death date are specific and known anchors of the other two time metrics, assessing the onset of disability is less precise. Individuals may have become disabled at any time during the interval between assessments (or prior to entry to the study).

Time-to-death

Mortality status and date of death for deceased participants were obtained from public death records. On average, individuals’ deaths occurred 4.78 years (SD = 3.63; range: 0–15 years) after their initial assessment and 1.42 years (SD = 1.99; range: 0–10 years) after the last assessment in which they took part.

The 365 persons included in the analysis were born between 1897 and 1914, and on average, experienced disability 86.90 years later (SD = 2.75; range: 79–95 years). They died at an average age of 90.85 years (SD = 4.00; range: 82–103 years) and participated in an average of 2.43 (SD = 1.29) assessments, with n = 253 or 69% contributing two or more data points. In total, the 851 observation points simultaneously span the 79 to 98 year age range (mean = 87.39, SD = 3.20), a 16-year range from eight years prior to eight years after disability onset (mean = 0.47, SD = 2.38), and the 15 to 0 years (mean = 4.13, SD = 3.32) prior to death.

Between-person: Time as Resource/Burden Measures

Corresponding to primary, secondary, and tertiary aging, we calculated three resources/burdens between-person metrics, time-lived, time-disabled, and time-left. For this illustration, we conceptualize and interpret these metrics from an ‘aging-as-decline’ (burden) perspective. Note, however, that complementary interpretations are also possible.

Time-lived

We considered two separate time-lived variables that provided meaningful and practical metrics for between-person comparisons regarding the age-related burdens people carried: The number of years of life accumulated at disability onset (M = 86.90 years; SD = 2.75; range = 79–95) and the number of years of life accumulated at death (M = 90.85 years; SD = 4.00; range = 82–103). For reasons that will become clear later (i.e., time-to/from-disability was used at the within-person level), we used time-lived at disability onset in our final models.

Time-disabled

The level of disability-related burdens an individual experienced was calculated, at a common point of assessment, as the number of years that he or she had spent in disability. Using the event of death as the reference allowed for preponderant interindividual differences that could be used as a meaningful predictor (M = 3.95 years; SD = 3.26; range = 0–14). This highlights the post-hoc nature of resources/burdens, in that people unfortunately must have died before we can tally how much time they had accumulated or spent in various states over their lifetime. Ideally, we would like to obtain such measures when people are still alive, so that the measures would actually have some prospective predictive value. The tradeoff, though, is that without a meaningful point for comparison (e.g., disability onset or death) across all persons, the tally of “trait-like” resources/burdens would be in many ways arbitrary, and likely non-invariant. For example, from birth through the first onset of disability, lifetime-disabled is zero for all persons. Here, the between-person metrics are stable between-person differences because they are calculated post-hoc on a sample that did become disabled, and did die. Live samples, or individuals who never experienced disability would be less convenient in this regard.

Time-left

In complement to time-lived, amount of time-left was also calculated in two ways: the number of years of life left to live at birth (i.e., age-at-death; M = 90.85 years; SD = 4.00; range = 82–103) and number of years of life left to live at disability onset (M = 3.95 years; SD = 3.26; range = 0–14). We used the former in our final models.

Data Analysis and Results

Corresponding to the time-as-process and time-as-resources/burdens distinction, the data were analyzed in two steps.

Within-person: Time-as-process

Our first task was to determine whether observed within-person changes in memory were primarily driven by primary, secondary, or tertiary aging processes. Three polynomial growth models were specified as

| (1) |

where person i’s memory performance at time t, memoryti, is a function of an individual-specific intercept parameter, β0i, and individual-specific slope parameters, β1i, β2i, β3i, that capture rates of linear, quadratic, and cubic change over the selected time-as-process variable (age, time-to/from-disability, or time-to-death), and residual error, eti. Following standard multilevel or latent growth modeling and model selection procedures (e.g., McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003; Ram & Grimm, 2007; Singer & Willett, 2003), individual-specific intercepts and slopes (βs from the Level 1 model given in Equation 1) were modeled as

| (2a) |

(i.e., Level 2 model) where interindividual differences, u0i and u1i are assumed to be normally distributed, correlated with each other, and uncorrelated with the residual errors, eti for which a variety of error structures were explored (e.g., compound symmetry, autoregressive, toeplitz) and an identity or diagonal structure selected. The relative fit of all three growth models to the same data were examined to determine the better time-as-process representation. Fit statistics were, for the age model AIC = 5,910; time-to/from-disability model AIC = 5,875; and time-to-death model AIC = 5,879, where lower AIC indicates better relative model fit. The time-to/from-disability model fit the data best, indicating that the observed changes in memory were best represented as being driven by disability-related (i.e., secondary aging) processes.

Between-persons: Time-as-resources

After establishing that the time-varying proxy for secondary aging processes provided the best representation of the interindividual differences in within-person changes, we examined if and how the resources/burden variables corresponding to the other aspects of aging (e.g., primary and tertiary burdens) moderated those changes. Specifically, we introduced time-as-resources variables as predictors at the between-person level of the model,

| (2b) |

where the interindividual differences in intercept and slopes are now predicted by two time-as resources/burdens variables, A= time-lived, B = time-left, and their interaction, at the between-person level. Model parameters are interpreted with respect to how changes in one aging process (e.g., disability-related processes) may be moderated by differences in the other two aspects of aging (e.g., age-burden, mortality-burden). Results from the final model are shown in Table 1. Quadratic and additional interaction effects were tested but were not significant and not included in the final model.

Table 1.

Polynomial Growth Models for Memory over Time-to/From-Disability.

| Parameter | Memory Recall

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | |

| Fixed effects | ||

| Intercepta, γ00 | 3.801 * | (0.190) |

| Time-to/from-disability, γ10 | − 0.489 * | (0.051) |

| Time-to/from-disability3, γ20 | − 0.004 * | (0.001) |

| Study membershipb | 0.898 * | (0.317) |

| Time-lived, γ01 | − 0.032 | (0.057) |

| Time-left, γ02 | 0.178 * | (0.046) |

| Time-lived x time-left, γ03 | − 0.006 | (0.017) |

| Time-lived x time-to/from-disability, γ11 | − 0.024 | (0.013) |

| Time-left x time-to/from-disability, γ12 | 0.031 * | (0.012) |

| Time-lived x time-left x time-to/from-disability, γ13 | 0.002 | (0.004) |

| Random effects | ||

| Intercept, σ2u0 | 6.128 * | (0.588) |

| Time-to/from-disability, σ2u0 | 0.049 * | (0.027) |

| Cov. Intercept with time-to/from-disability, σu0u1 | 0.288 * | (0.100) |

| Residual, σ2e1 | 3.341 * | (0.408) |

| Residual, σ2e2 | 1.728 * | (0.294) |

| Residual, σ2e3 | 1.660 * | (0.328) |

| Residual, σ2e4 | 3.077 * | (0.740) |

| Residual, σ2e5 | 2.749 * | (1.400) |

| −2LL | 3,878 | |

| AIC | 3,914 | |

Note. Unstandardized estimates and standard errors are presented.

= Intercept is centered at point of disability onset, t = 0;

= OCTO = 0, OCTO-TWIN = 1; Time-lived = age at disability onset; Time-left = years between disability onset and death. N = 365 who provided 851 observations. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; −2LL = −2 Log Likelihood, relative model fit statistics. Cov. = Covariance.

= p < .05.

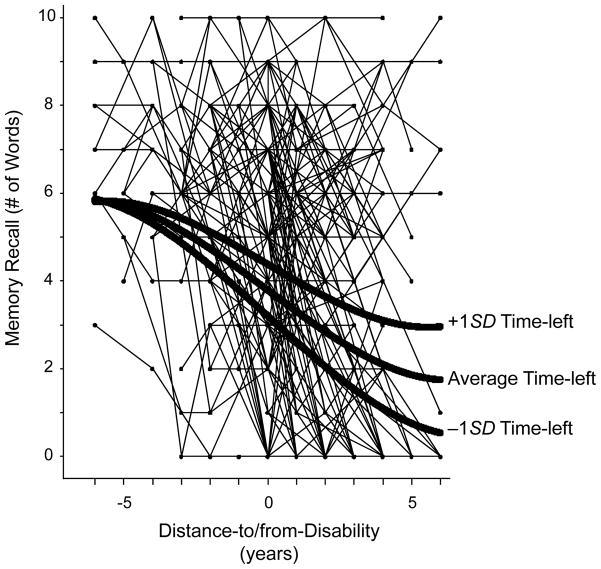

As seen in Figure 2, individuals’ memory performance progressed in relation to time-to/from disability, on average, at a linear rate of −0.489 words per year, reaching and continuing on from an average of 3.80 words at disability onset, with some deceleration or leveling-off several years after disability onset (as captured by the cubic trend). Level of memory performance at disability onset (intercept) was moderated by study membership (the OCTO-TWIN participants scored slightly better) and time-left (between-person measure of tertiary age). In particular, greater time-left (i.e., greater resources) at disability onset was associated with higher levels of memory performance, γ02 = +0.178. In addition, interindividual differences in disability-related change were moderated by level of tertiary aging resources, in that greater amount of time-left was significantly associated with less-steep linear declines in memory performance, γ12 = +0.031. No other interactions were significantly different than zero. The general interpretation is that, in this sample, secondary and tertiary aging both play a role in how between-person differences in within-person changes in memory performance manifest in late-life, whereas the role of primary aging is rather minor.

Figure 2.

Time-left (tertiary age) moderates the amount of decline in memory recall performance over time-to/from-disability (secondary aging). Participants who were closer to death at the onset of disability (i.e., those with fewer resources; −1 SD time-left) showed steeper disability-related memory decline than participants who were further away from death at the onset of disability (i.e., those with greater resources; +1 SD time-left).

Discussion

One of the key objectives developmental researchers face is to describe development in terms of intraindividual changes across time (Baltes & Nesselroade, 1979; Wohlwill, 1973). Chronological age, as an easily measured proxy for a set of unobserved age-related processes, has been and is used as the chief variable on which to index these changes. Employing age as a continuous predictor, growth models and similar techniques are often used to describe how individuals’ behavior changes over time. Considering multiple proxies for unobserved aging processes, we found that chronological age may not always be the best index on which to track developmental change. Instead, the changes in memory observed in our sample were described by a model where the progression of secondary aging processes was moderated by tertiary age burdens. While many people assume late-life changes are driven by aging processes, these results provide further empirical evidence implicating disablement (e.g., Comijs et al., 2005; Lucas, 2007) and mortality (Backman & MacDonald, 2006; Diehr, et al., 2002; Gerstorf, Ram, et al. 2008; Johansson et al., 2004; Sliwinski et al., 2006; Thorvaldsson, et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2003) as major forces underlying cognitive development in late life.

Beyond the substantive implications of our findings, the motivation for this article was to explore how multiple aspects of aging, or more generally, time can be incorporated within the growth curve modeling framework. Parsing the model into its component parts, we illustrated how three time variables could be incorporated simultaneously. Brought in at the within-person, longitudinal level, time-varying indices such as age, time-to/from-disability, and time-to-death serve to organize repeated measurements and can be used to extract systematic patterns of change that proceed in conjunction with the passage of time – intraindividual change. The time-varying variables serve as easy-to-measure latent indicators of the conglomerate of causes of change – as proxy for process. Brought in at the between-person, cross-sectional level, time-lived, time-disabled, and time-left can all be used, at a meaningful point of observation, to index interindividual differences in the accumulation of experience. The variables are treated as inherent characteristics of the person and their life span – as proxy for time-related resources or burdens that were accumulated or spent (Heirich, 1964).

The time variables, both process and resource/burden versions, invoked in this illustration all make use of calendar time. That is, all are indexed and scaled in years (e.g., years from birth, years in disability, etc.). However, this is only one of many units that may be used to quantify time (see also Schaie, 1986). Other possibilities include social time, psychological time, subjective time, biological time, and so on (Baars & Visser, 2007; Birren & Cunningham, 1985; Sorokin & Merton, 1937; Settersten & Mayer, 1997; Wohlwill, 1973). For example, rather than using the number of years lived as a proxy for accumulated experience, neurobiological or cultural-social ‘clocks’ could be used to measure change and/or time-related resources (cf. Featherman & Petersen, 1986; Li & Schmiedek, 2002; e.g., burden of disability on a biological or functional metric rather than calendar metric). Given the generality of the growth curve modeling framework, in that statistical models accept without prejudice variables of many shapes and sizes, all such possibilities can and should be explored.

Even before some of us were born, Schaie (1965) proposed a theoretical framework for disentangling multiple aspects of time, age (A), cohort (C), and period (T) – the general developmental model. Sequential study designs provided some hope for unconfounding age, cohort, and time-of-measurement (period) variance. Insights obtained in the subsequent years have provided further understanding of when and how these components of developmental change can be estimated. For example, Schaie (1986) discussed the role of cohort as a selection or between-person variable – individuals’ membership or non-membership in a cohort does not change over time. As such cohort can be used as a predictor of between-person differences in age-related change. Although still requiring a fully elaborated connection to A, C, T concepts, we attempt to draw a parallel to the current effort to distinguish primary, secondary, and tertiary aspects of aging. Following a few years after Schaie’s discussion, we distinguish how process and resources aspects of time can be invoked as within-person or between-person variables within the growth curve model. Although the specific variables and modeling framework are different, the general form of the possibilities and constraints is the same. Process and resources/burdens-based proxies for primary, secondary and tertiary aging are not replacements for A, C, and T. They simply provide a different, substantively based decomposition of the within- and between-person variance present in longitudinal panel data – a decomposition that is subject to many of the same convergence assumptions, internal validity threats (e.g., practice effects and their interactions with time-left), multicollinearity problems, and resulting difficulties in accurately separating the independent effects of each type of time (Hertzog & Nesselroade, 2003). As do A, C, and T, the process- and resources/burdens-based time variables discussed here provide a general framework that can inform longitudinal study designs, particularly with respect to how event-based (birth, disability, death, etc.) sampling can be used to explicate and disentangle multiple aspects of ageing. As we explore further how time, statistical models, and study designs can be integrated efficiently and effectively, we look forward to obtaining a fuller description of the many factors that contribute to developmental change. Many thanks to KWS for laying the footprints for us to follow.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge grant funds provided by the Center for Population Health and Aging at Penn State University (NIH/NIA Grant R03 AG028471-01) to combine the datasets, The European Union project contract no. QLK6-CT-2001-02283 and the Research Board in the County Council of Jönköping, and the Research Council in the Southeast of Sweden for their funding of the OCTO study, NIA grant AG-08861 for the funding of the OCTO-Twin study.

The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to Stig Berg, who was an instrumental leader in the collection of the Swedish datasets, and who’s research career contributed significantly to the current study. Special thanks also to Gerald McClearn from Penn State University, Boo Johansson from the University of Göteborg, and the research teams at the Institute for Gerontology in the College of Health Sciences at Jönköping University in Sweden, the Center for Developmental and Health Genetics at the Pennsylvania State University, and the Division of Genetic Epidemiology at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden for their design and collection of the original data.

References

- Alwin DF, Hofer SM, McCammon RJ. Modeling the effects of time: Integrating demographic and developmental perspectives. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 6. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Austad SN. Concepts and theories of aging. In: Masoro EJ, Austad SN, editors. Handbook of the biology of aging. 5. New York: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Baars J, Visser H, editors. Aging and time: Multidisciplinary perspectives. Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman L, MacDonald SWS. Death and cognition: Synthesis and outlook. European Psychologist. 2006;11:224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Nesselroade JR. History and rationale of longitudinal research. In: Nesselroade JR, Baltes PB, editors. Longitudinal research in the study of behavior and development. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Berg S. Aging, behavior, and terminal decline. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 4. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Birren JE, Cunningham WR. Research on the psychology of aging: Principles, concepts and theory. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 2. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1985. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Busse EW. Theories of aging. In: Busse EW, Pfeiffer E, editors. Behavior and adaptation in late life. Boston, MA: Little & Brown; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Comijs HC, Dik MG, Aartsen MJ. The impact of change in cognitive functioning and cognitive decline on disability, well-being, and the use of healthcare services in older persons: Results of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2005;19:316–323. doi: 10.1159/000084557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehr P, Williamson J, Burke GL, Psaty BM. The aging and dying processes and the health of older adults. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2002;55:269–278. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherman DL, Petersen T. Markers of aging: Modeling the clocks that time us. Research on Aging. 1986;8:339–365. doi: 10.1177/0164027586008003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Ram N, Estabrook R, Schupp J, Wagner GG, Lindenberger U. Life satisfaction shows terminal decline in old age: Longitudinal evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) Developmental Psychology. 2008a;44:1148–1159. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Alecxih L, Branch LG, Wiener JM. Medical and long-term care cost when older persons become more dependent. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1244–1245. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heirich M. The use of time in the study of social change. American Sociological Review. 1964;29:386–397. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Nesselroade JR. Assessing psychological change in adulthood: An overview of methodological issues. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:639–657. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B, Hofer SM, Allaire JC, Maldonado-Molina M, Piccinin AM, Berg S, et al. Change in memory and cognitive functioning in the oldest-old: The effects of proximity to death in genetically related individuals over a six-year period. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:145–156. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B, Zarit SH. Prevalence and incidence of dementia in the oldest-old: A longitudinal study of a population-based sample of 84–90-year-olds in Sweden. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1995;10:359–366. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199701)12:1<53::aid-gps507>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness and the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–923. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleemeier RW. Intellectual change in the senium. Proceedings of the Social Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association. 1962;1:290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Schmiedek F. Age is not necessarily aging: Another step towards understanding the ‘clocks’ that time aging. Gerontology. 2002;48:5–12. doi: 10.1159/000048917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE. Long-term disability is associated with lasting changes in subjective well-being: Evidence from two nationally representative Longitudinal Studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:717–730. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Nesselroade JR. Growth curve analysis in contemporary psychological research. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of psychology: Research methods in psychology. Vol. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. pp. 447–480. [Google Scholar]

- McClearn G, Johansson B, Berg S, Ahern F, Nesselroade J, Pedersen N, Petrill S, Plomin R. Substantial genetic influence on cognitive abilities in twins 80+ years old. Science. 1997;276:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5318.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Grimm KJ. Using simple and complex growth models to articulate developmental change: Matching theory to method. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. A general model for the study of developmental problems. Psychological Bulletin. 1965;64:91–107. doi: 10.1037/h0022371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. Beyond calendar definitions of age, time and cohort: The general developmental model revisited. Developmental Review. 1986;6:252–277. [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW, Hofer SM. Longitudinal studies in aging research. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 5. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 53–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schroots JJF, Birren JE. Concepts of time and aging in science. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 3. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Bruce ML, McAvay GJ. Social network characteristics and onset of ADL disability: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1996;51B(4):S191–S200. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.4.s191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA, Mayer KU. The measurement of age, age structuring, and the life course. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:233–261. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski MJ, Hofer SM, Hall C, Buschke H, Lipton RB. Modeling memory decline in older adults: The importance of preclinical dementia, attrition, and chronological age. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:658–671. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski MJ, Stawski RS, Hall RB, Katz M, Verghese J, Lipton RB. On the importance of distinguishing pre-terminal and terminal cognitive decline. European Psychologist. 2006;11:172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin PA, Merton RK. Social time: A methodological and functional analysis. American Journal of Sociology. 1937;5:615–629. [Google Scholar]

- Thorvaldsson V, Hofer SM, Johansson B. Ageing and late life terminal decline: A comparison of alternative modeling approaches. European Psychologist. 2006;11:196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Terminal decline in cognitive function. Neurology. 2003;60:1782–1787. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000068019.60901.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlwill JF. The study of behavioral development. Oxford, UK: Academic Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Johansson B, Berg S. Functional impairment and co-disability in the oldest old: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993;5:291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Johansson B, Malmberg B. Changes in functional competency in the oldest-old: A longitudinal study. Journal of Aging and Health. 1995;7:3–23. doi: 10.1177/089826439500700101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]