Abstract

This article reports on the development and validation of a novel, objective test of judgment for use with older adults. The Test of Practical Judgment (TOP-J) is an open-ended measure that evaluates judgment related to safety, medical, social/ethical, and financial issues. Psychometric features were examined in a sample of 134 euthymic individuals with mild Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or cognitive complaints but intact neuropsychological performance (CC), and demographically-matched healthy controls (HC). Measures of reliability were adequate to high, and TOP-J scores correlated with select measures of executive functioning, language, and memory. AD participants obtained impaired TOP-J scores relative to HCs, while MCI and CC participants showed an intermediate level of performance. Confirmatory factor analyses were consistent with a unidimensional structure. Results encourage further development of the TOP-J as an indicator of practical judgment skills in clinical and research settings. Longitudinal assessments are being performed to examine predictive validity of the TOP-J for cognitive progression in our clinical groups.

Judgment can be defined as the capacity to assess situations and draw sound conclusions after careful consideration of the relevant circumstances. From a neuropsychological perspective, judgment falls under the domain of executive functioning (Woods, Patterson, & Whitehouse, 2000) and includes both a cognitive appraisal process (i.e., determining what to do in a situation) and the behavioral follow-through (i.e., engaging in the adaptive/safe behavior). Numerous processes are involved in the execution of good judgment including generating appropriate strategies to approach a problem, identifying suitable goals, shifting from one idea to another, evaluating the potential consequences of different courses of action, inhibiting inappropriate responses, initiating and carrying out purposeful behavior, and monitoring the progress and effectiveness of a chosen solution. In the absence of practiced routines for solving problems in unstructured situations, individuals with compromised executive functioning may exercise poor judgment for a variety or reasons. For example, they may make impulsive decisions based on inadequate exploration of pertinent issues, fixate on a single solution due to compromised mental flexibility, or fail to consider the long-term consequences of their solutions (Channon, 2004; Thornton & Dumke, 2005; Woods et al., 2000).

In addition to executive functioning, judgment relies upon other cognitive processes including aspects of memory and language. For example, when making difficult decisions it is often useful to call to mind relevant past experiences and practical knowledge. Additionally, successful problem solving and good judgment rely upon the ability to comprehend complex aspects of verbal and non-verbal language and effectively communicate one’s decision to others involved (Allaire & Marsiske, 1999; Marson & Harrell, 1999). Social and emotional skills also play a role in judgment, including perspective taking, empathizing, understanding the ramifications of a situation for others, appreciating the subtleties of the social context in which events are occurring, balancing competing social priorities and obligations, and responding appropriately to environmental or social feedback (Blanchard-Fields, Stein, & Watson, 2004; Channon, 2004).

Loss of judgment ability is a common consequence and diagnostic feature of dementia, as executive cognitive functions that permit complex, goal-directed use of existing knowledge progressively fail (Duke & Kaszniak, 2000; Karlawish, Casarett, James, Xie, & Kim, 2005; Knopman et al., 2001; LaFleche & Albert, 1995; Marson & Harrell, 1999). Neuropsychologists often assess judgment when conducting evaluations of older adults with suspected dementia (Borgos, Rabin, Pixley, & Saykin, 2006b), and this knowledge can inform decisions about diagnosis, functional and cognitive competence, and treatment (Bertrand & Willis, 1999; Karlawish et al., 2005; Kim, Karlawish, & Caine, 2002; Willis et al., 1998). For example, dementia patients who are unaware of their judgment deficits may persist in behaviors that are no longer safe, such as using the stove, driving, or managing finances or prescription medications without assistance. Patients and their family members can be educated about the nature and consequences of impaired judgment skills and the relationship of observed symptoms to the disease process. With this information, caregivers may be better prepared to assume new responsibilities within the family system or provide the necessary structure and supervision to reduce the likelihood of dangerous incidents (Duke & Kaszniak, 2000).

Despite the need for instruments to assess judgment abilities in the growing number of elders with cognitive decline, there appears to be a lack of clinically useful, ecologically relevant, and psychometrically sound tools for this purpose. A comprehensive search of the literature revealed only two standardized neuropsychological tests of judgment: (a) the Judgment Questionnaire subtest of the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Exam (NCSE JQ; Northern California Neurobehavioral Group, Inc., 1988) and (b) the Judgment/Daily Living subtest of the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB JDG; Stern & White, 2003). These instruments have several limitations, particularly when utilized with older adults. For example, Woods et al. (2000) evaluated the utility of the NCSE JQ and found significant content and statistical problems, including the insensitivity of this measure to impaired judgment in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. Drane and Osato (1997) also found that scores on the NCSE JQ failed to discriminate dementia patients from healthy older adults. The 10-item NAB JDG (Stern & White, 2003) appears to possess better psychometric properties (see Results section); however, the test items deal predominantly with basic safety and hygiene issues rather than everyday, high-level judgment dilemmas. Further, answers typically require a statement about why something is dangerous rather than how one would personally resolve a situation requiring real-world judgment or decision-making skills.

In a recent survey of neuropsychologists, approximately 90% of respondents indicated the need for additional/improved standardized tests of judgment (Borgos et al., 2006b). Survey results also indicated that the most commonly used tests to assess judgment were the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; Heaton, Chelune, Talley, Kay, & Curtiss, 1993) and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition (WAIS-III) Comprehension subtest (Wechsler, 1997), which received mention by 37% and 31% of the 285 respondents, respectively. Cited less frequently were the NCSE JQ and NAB JDG, which received mention by 14% and 6% of survey respondents, respectively. While providing useful information about aspects of executive functioning, the WCST and WAIS-III Comprehension were not designed to assess judgment skills and may fail to capture cognitive processes and content areas associated specifically with judgment. WAIS-III Comprehension, for example, requires individuals to draw upon general knowledge about social rules and conventions and to abstract the meaning of proverbs rather than generate solutions to complex, real-world problems about medical or financial matters.

Cognitive constructs that overlap with judgment include everyday problem solving, everyday decision making, social problem solving, and practical intelligence (Marsiske & Margrett, 2006; Thornton & Dumke, 2005; Willis, 1996), and objective measures of these constructs include the following: Predicaments Task (Channon & Crawford, 1999), Reflective Judgment Dilemmas (Kajanne, 2003), Practical Problems Test (Denney & Pearce, 1989); Everyday Cognition Battery (Allaire & Marsiske, 1999); Everyday Problems Test (Willis & Marsiske, 1993), Everyday Problem Solving Inventory (Cornelius & Caspi, 1987), Everyday Problems Test for Cognitively Challenged Elderly (EPCCE; Willis, 1993; Willis et al., 1998), and the Direct Assessment of Functional Status (Lowenstein et al., 1989). Instruments also have been developed to assess competence to consent to medical treatment and/or research (see Fitten, Lusky, & Hamann, 1990; Grisso, Appelbaum, & Hill-Fotouhi, 1997; Marson, Hawkins, McInturff, & Harrell, 1997; Marson, Schmitt, Ingram, & Harrell, 1994; Vellinga, Smit, van Leeuwen, van Tilburg, & Jonker, 2004). Taken together, these measures provide useful information about factors contributing to successful and unsuccessful everyday problem solving and decision making about one’s medical care. These tests, however, were developed primarily for research purposes and are not routinely utilized by neuropsychologists. Many lack detailed information about their psychometric properties (including norms, cutoff scores, and measures of reliability and validity) and clinical utility when included as part of a clinical assessment battery. In addition, some instruments (e.g., EPCCE) were designed for elderly individuals known to have deficits in cognitive functioning and therefore might not be appropriate for use in preclinical stages of dementia.

We developed the Test of Practical Judgment (TOP-J) in response to the need for a brief, clinically relevant measure of everyday judgment in older adults. This paper describes the development and validation process of the TOP-J including item selection, scale development, and preliminary psychometric properties (i.e., reliability, validity, and dimensionality). Another goal was to investigate the TOP-J’s ability to detect differences in groups of older adults in various stages of cognitive decline. Participants included nondepressed older adults diagnosed with probable mild AD or amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and demographically matched healthy controls (HC). MCI is conceptualized as a transition state between normal cognitive aging and the earliest clinical features of dementia (Petersen, 2004; Winblad et al., 2004). Though impaired executive functioning is a prominent feature of dementia, research has yet to determine at which point during the disease course judgment skills first become affected. We also included a fourth group of healthy, nondepressed older adults who present with significant cognitive complaints (CC) but who perform normally on neuropsychological testing. Recent research suggests that CCs show structural brain changes intermediate between those seen in MCI and those seen in healthy older adults without such complaints (Saykin et al., 2006). Thus, inclusion of participants with MCI and CCs permitted preliminary investigation of the relative preservation or impairment of judgment ability in preclinical stages of neurodegenerative disease.

METHOD AND PROCEDURE

Participants

The Dartmouth Memory and Aging Study is a longitudinal investigation of memory and other cognitive processes in older adults in the preclinical and early stages of dementia. Comprehensive assessment included neuropsychological evaluation, structural and functional neuroimaging, and genotyping. Participants were recruited from flyers, public lectures, newspaper advertisements, and referrals from medical center clinics. They provided written informed consent according to procedures approved by the institutional Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. Comprehensive screening included a standardized phone interview and memory screen (Rabin et al., 2004), in-person interview, and medical chart review. Participants were at least 60 years of age, right-handed, and fluent in English, and they had a minimum of 12 years of formal education. Each participant had a knowledgeable collateral informant (i.e., an individual who knew the participant well and could answer questions about his or her cognition and general health). Exclusion criteria included any significant or uncontrolled medical, psychiatric, or neurological condition (other than AD or MCI) that could affect brain structure or cognition, history of head trauma with loss of consciousness lasting more than five minutes, and current or past history of substance dependence.

Participants underwent detailed neuropsychological evaluation, including measures of memory, attention, executive function, language, spatial ability, general intellectual functioning, and psychomotor speed, as well as standard dementia screens and self- and informant-report measures. All tests were administered by postdoctoral fellows or highly trained technicians. Level of cognitive complaint was determined from responses on multiple self- and informant-report measures, and a Cognitive Complaint Index (CCI) was calculated as the percentage of all items endorsed by the participant and/or the informant (Saykin et al., 2006). Appendix A provides a list of instruments administered during the assessment process. A Board-certified geropsychiatrist conducted a semi-structured interview to rule out depression or other psychiatric disorders. Blood samples were obtained to determine apolipoprotein E (apoE) genotype. Participants underwent structural brain magnetic resonance imaging scans (MRIs), which were reviewed by a Board-certified neuroradiologist to rule out incidental pathology.

A panel of neuropsychologists and a geropsychiatrist reviewed the evaluation results at a weekly consensus conference to determine group classification. ApoE status, functional neuroimaging findings, and TOP-J performance were not considered during the diagnostic process. Table 1 presents a summary of classification criteria. The AD group met criteria for a diagnosis of probable mild AD, as defined by the NINCDS-ADRDA1 criteria (McKhann et al., 1984). The MCI group met criteria developed by Petersen et al. (2001a, 2001b) for amnestic MCI. Participants were classified as CC based on the following criteria: (a) significant memory complaints, (b) normal activities of daily living, (c) normal cognitive functioning, and (d) no dementia, depression, or other psychiatric disorder that would account for or contribute to the cognitive complaints. Participants were classified as HC if they showed: (a) no significant cognitive complaints, (b) normal activities of daily living, (c) normal cognitive functioning, and (d) no dementia, depression or other psychiatric disorder.

TABLE 1.

Criteria used to classify study participants

| HC | CC | MCI | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal memory performancea | √ | √ | ||

| Significant memory complaints, corroborated by an informantb | √ | √ | √ | |

| Preserved general cognitive functioning | √ | √ | √ | |

| Generally normal activities of daily living | √ | √ | √ | |

| No dementia | √ | √ | √ | |

| No depression or other psychiatric disorder | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Note. HC: healthy control; CC: cognitive complaints; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; AD: Alzheimer’s disease.

Approx. 1.5 SD below the mean established for age- and education-matched controls on standardized tests of episodic memory.

Endorsed at least 20% of possible cognitive complaints across all subjective report inventories or complaints deemed clinically significant by consensus of the research team.

Study participants were consecutively enrolled or longitudinally followed in the Dartmouth Memory and Aging Study and included 14 patients with probable mild AD, 34 patients with amnestic MCI, 35 older adults with significant cognitive complaints despite normal cognition (CC), and 39 demographically matched older adults with no cognitive complaints or deficits (HC). An additional 12 patients with probable AD were recruited from our clinical service to complete the TOP-J, NCSE JQ, and phone interview despite not being eligible or willing to participate in the full study. Reasons for their ineligibility included current use of psychoactive medications (e.g., antidepressant, cholinesterase inhibitor), unwillingness or inability to undergo MRI, or comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease. These individuals did not differ from the other AD patients with regard to TOP-J total score, t(24)=0.27, ns, age, t(24)=−0.99, ns, gender, χ2(1, n=26)=1.5, ns, or level of education, t(24)=−1.3, ns. We therefore combined all AD participants into a single group (n=26) for subsequent analyses and discussion.

Select demographic and neuropsychological variables are presented in Table 2. There were no significant group differences in gender, education, or apoE ε 4 allele status. AD participants were slightly older than members of the HC group. As expected, based on the study classification criteria, performance on the Dementia Rating Scale–2 (Jurica, Leitten, & Mattis, 2001) and Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) was lower in MCI and AD than that in the other groups, though MCI participants scored above the respective cutoff scores for dementia. Similarly, MCI and AD participants showed significant deficits on tests of memory—for example, California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition (CVLT-II; Delis, Kramer, Kaplan, & Ober, 2000) and Wechsler Memory Scale, Third Edition (WMS-III; Psychological Corporation, 1997)—relative to HCs and CCs. The Cognitive Complaint Index was elevated in the AD, MCI, and CC groups relative to HCs (p < .001). Post hoc comparisons using Bonferroni correction indicated that the CC, MCI, and AD groups did not differ from each other, and participants from these groups endorsed more than three times as many complaints as the control group. Though no participant was clinically depressed or scored in the depressed range on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), CC and AD participants tended to endorse several more items than did HCs (see Table 2). The sample was predominantly Caucasian, with one Asian and one Hispanic participant, consistent with the demographic composition of the surrounding region.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive information for participant groups

| Characteristic | HC (n=39) | CC (n=35) | MCI (n=34) | AD (n=26) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 71.7 (5.1) | 73.9 (6.3) | 73.8 (6.3) | 76.6 (6.8) | .02h |

| Educationa | 16.8 (2.6) | 16.4 (3.0) | 16.4 (3.0) | 15.4 (3.1) | ns |

| Gender (M, F) | 12, 27 | 11, 24 | 16, 18 | 14, 12 | ns |

| ApoE ε 4 (−,+)b | 19, 19 | 26, 9 | 15, 17 | 6, 6 | ns |

| CCI c | 7.1 (5.5) | 24.4 (9.4) | 30.4 (12.0) | 37.6 (10.5) | .000i |

| DRS-2d | 141.7 (1.7) | 141.2 (2.0) | 137.6 (4.1) | 123.0 (13.2) | .000j |

| MMSEe | 29.0 (1.1) | 28.8 (1.3) | 26.8 (1.5) | 22.9 (4.7) | .000j |

| CVLT4 | |||||

| Learning | 50.8 (7.8) | 46.3 (8.6) | 34.2 (6.5) | 23.2 (7.7) | .000j |

| Delay | 11.97 (2.4) | 11.1 (2.9) | 8.0 (2.9) | 4.7 (3.5) | .000j |

| GDSg | 1.3 (2.0) | 4.2 (4.0) | 3.0 (2.8) | 4.4 (4.3) | .000k |

Note. Data are mean (SD) except where indicated. HC: healthy control; CC: cognitive complaints; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; AD: Alzheimer’s disease.

In years.

ApoE ε 4=genotype of apolipoprotein E, ε 4−, ε 4+. Data were unavailable for 1 HC, 2 MCI, and 14 AD participants.

Cognitive Complaint Index: percentage of all complaint items endorsed in a positive (i.e., symptomatic) direction. See text for references for component scales. Data were unavailable for 12 AD participants.

Dementia Rating Scale-2, total score (n/144). Data were unavailable for 8 AD participants.

Mini-Mental State Examination, total score (n/30). Data were unavailable for 5 AD participants.

California Verbal Learning Test II, total learning score (n/80); Long Delay Free Recall (n/16). Data were unavailable for 6 AD participants.

Adjusted Geriatric Depression Scale (n/26 noncognitive items). Data were unavailable for 4 AD participants.

AD > HC.

CC, MCI, AD > HC.

HC, CC > MCI > AD.

HC < CC, AD.

Development of measure

Our overall goal was to develop a clinically useful and psychometrically sound measure of judgment in older adults that would be easy to administer, score, and interpret. Item development commenced with a review of the psychological and neuropsychological literature related to the clinical assessment of judgment. We next reviewed research on problem solving, medical decision making, and related executive processes in older adults. Colleagues in neuropsychology were asked about their use of the term “practical judgment” and what domains this term might encompass. In addition, Dartmouth Memory and Aging Study participants and their informants occasionally mentioned experiencing difficulties with aspects of judgment, and these comments were compiled. This comprehensive data-gathering process yielded four content domains: (a) safety, (b) medical, (c) social/ethical, and (d) financial matters. Given the goal of developing a brief instrument, other potential categories identified in the literature (e.g., consumerism, home management, family conflict resolution) were not a primary focus.

After establishing the content domains, we created a group of scenarios thought to be ecologically representative of the kinds of judgment problems regularly faced by older adults. Several goals guided our item development process. Items should be straightforward and easily understood, yet complex enough to require active problem solving and consideration of options and potential consequences of various courses of action. To maximize face and content validity, most items were based on actual situations reported by older adults in our study. We anticipated that respondents would draw upon crystallized information and social/personal knowledge about the world when answering the questions posed to them. Therefore, we strove to create scenarios for which the generation of successful solutions would also require higher order executive cognitive abilities. A related goal was to develop items appropriate for both high- and low-functioning examinees to avoid ceiling and floor effects. We sought to minimize the amount of structure imposed on participants and therefore chose an open-ended response format in which participants would listen to brief scenarios and report aloud their proposed solutions. During administration, use of prompts to guide participants was minimized, though examiners were instructed to query ambiguous, incomplete, or multiple responses. In such cases, the examiner would say: “Tell me more about that” or “Explain what you mean.”

The authors reviewed the initial pool of 20 items and identified those that were redundant or potentially confusing; 17 items were retained. Preliminary scoring criteria were developed based on theoretical and practical considerations. Specific score values were assigned to each unique response and groups of responses with the same salient elements. Scores per response ranged from 0 to 2 (0=poor, 1= adequate, 2=good). To score items, the examiner matched the examinee’s response against sample responses listed with each item; though not an exhaustive list, sample responses encompassed a broad range of possible replies. Unusual responses were judged according to their degree of similarity with sample responses in terms of specific content or general meaning. Because we were trying to measure judgment rather than idea fluency, only one response per test item was scored. In cases where examinees spontaneously gave multiple responses to an item, and it was not clear which was the intended response, examiners were instructed to query (i.e., “You stated x, y, and z—which is your final response?”).

The initial test version was administered over the telephone to 45 participants. After these pilot data were collected, we re-evaluated all test items and scoring criteria. Two questions were dropped due to problems with aspects of their administration, scoring, or level of comprehension by participants. An additional 6 items were deleted based on preliminary factor analytic findings of low negative loadings on the unitary general TOP-J factor (see below). The final version contained 9 items, which were ordered randomly on the test protocol. Scoring criteria were revised based on actual participant responses and feedback from neuropsychology colleagues until we attained a final set that could be used reliably. Individual responses were now scored on a 4-point scale (0, 1, 2, or 3 points) to reflect a greater range and variety of possible responses, with a higher number indicating better judgment. Total score was derived by summing the 9 items (range 0–27). The content of the test items were as follows (items presented are numbered according to their placement on the 9-item TOP-J protocol. Appendix B provides two sample items, along with complete scoring criteria.

Runs out of medication while vacationing.

Caller asks for financial/personal information.

While vacationing realizes stove possibly left on.

Reads about important changes in social security benefits.

Learns of cancer risk associated with a current medication.

Starts having trouble with driving.

Finds wallet with money.

Finds small dog with a collar.

Financial advisor suggests changing investment portfolio.

As noted above, we administered the initial TOP-J version to 45 randomly selected study participants. These protocols were later rescored when the new criteria were implemented. TOP-J scores from the initial 45 protocols did not differ from those from the remainder of the sample, t(132) = 0.20, ns. The final test version was then added to our assessment battery and administered to all new and returning participants. The number of participants who received the TOP-J according to their year in the study was variable due to attrition and ongoing changes in our recruitment strategies, but was equivalent across participant groups: Year 1, 41; Year 2, 28; Year 3, 26; Year 4, 19; Year 5, 6; Year 6, 2; χ 2(15, n=122)=23.8, ns. Scoring of the first 65 protocols was accomplished by a single rater; these protocols were rescored by a second rater for interrater reliability analyses. A subsample of participants (n=50) received a second TOP-J administration for the purpose of establishing test–retest reliability.

To help establish content validity, we measured consensus regarding the assignment of each item to its corresponding subdomain. The test protocol was distributed to a group of 16 neuropsychologists and neuropsychology trainees who were asked to indicate the judgment domain(s) best represented by each item. Because the domains were not independent or mutually exclusive, raters ranked each item’s primary and secondary membership (if more than one content domain applied). This process served to refine and determine the feasibility of item-scale membership. Table 3 shows that the independent, expert raters agreed strongly (90% or more) with the intended scale for seven of the nine TOP-J items. For the 2 items with 69% agreement, expert raters agreed with the intended scale for their second choice. In developing the TOP-J, the authors recognized that the content of 4 items fell into more than one category. Given the relatively small number of total items and the overlap of content domains for almost half the test items, the recommended practice is to sum all TOP-J items into a single overall score.

TABLE 3.

Expert ratings for TOP-J items

| Content domain | Item | Secondary content domain | Raters’ primary choicea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | 1 | – | 100 |

| 5 | Safety | 94 | |

| Financial | 2 | Safety | 69 |

| 4 | – | 100 | |

| 9 | – | 100 | |

| Safety | 3 | – | 100 |

| 6 | Medical | 94 | |

| Social/ethical | 7 | – | 100 |

| 8 | Safety | 69 |

Note. Items presented above are numbered according to their placement on the 9-item TOP-J version.

% agreement with intended content domain.

RESULTS

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 12.0.1 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), Mplus 3.11 (Muthén and Muthén, 2004), and MedCalc (http://www.medcalc.be/). All reported analyses are for the 9-item TOP-J version, except where otherwise noted.

Reliability

Internal consistency, or item homogeneity, was examined using an alpha coefficient (Cronbach, 1951). With this method, scale consistency is determined by the interrelationships between items, accounting for the total number of items that the scale comprises. Simply put, alpha estimates the proportion of variance that is systematic or consistent in a set of test scores, and widely accepted cutoff scores in the social sciences range from approximately .60 to .80 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994; Santos, 1999). The alpha coefficient for the 134 TOP-J protocols was .63 (p < .001). One might expect a moderate alpha coefficient for a test such as the TOP-J, which is thought to involve several aspects of practical judgment skills through a set of items with diverse content. Additionally, .63 compares favorably with the overall average alpha of .45 reported for older adults on the NAB JDG (White & Stern, 2003) and with alpha values of .04 and .46 reported for AD patients and healthy older adults, respectively, on the NCSE JQ (Woods et al., 2000; see Table 4). In our sample, the alpha coefficient for the 115 NCSE JQ protocols was .07 (p > .05). Finally, item-to-total correlations and interitem correlations were calculated to ensure adequate associations between individual items and TOP-J total score and to rule out redundancy in test items. The average correlation of each item with the TOP-J total score was .51 (SD=.09), with no items correlating less than .36. The average interitem correlation was .17 (SD=.09), and no items correlated higher than r > .36, suggesting that the items tap reasonably independent content.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of reliability estimates for judgment tests

| Test | Internal consistency | Test–retest | Interrater |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOP-Ja | .63 | .78 | .95 |

| NAB JDGb | .45 | .37 | .85 |

| NCSE JQc | .04, .46, .07d | .69 | .69 |

Note. TOP-J=Test of Practical Judgment; NCSE JQ=Judgment Questionnaire subtest of the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Exam; NAB JDG=Judgment/Daily Living subtest of the Neu-ropsychological Assessment Battery. Reliability coefficients for the NAB JDG and NCSE JQ were taken from the secondary sources provided in the table. All reliability coefficients were based on samples of older adults with the exception of NAB JDG interrater reliability, which was based on a mixed sample of adults and older adults.

Current sample.

Denotes internal consistency calculated based on participants in the current study.

The first 65 protocols were scored by a single rater and then rescored by a second rater, both of whom were blind to participant group. Interrater reliability was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979). As shown in Table 4, interrater reliability for the TOP-J total score was .95 (p < .001) with a mean difference of 1.56 (SD=1.53). The test–retest sample included 50 participants who received a second TOP-J administration approximately 4 months after the first (M=15.94 weeks, SD=8.68). Diagnostic composition was 30% HC, 26% CC, 24% MCI, and 20% AD. Test–retest reliability was .78 (p < .001), and Time 1 scores (M=21.49, SD=4.24) did not differ significantly from Time 2 scores (M=21.41, SD=4.15). The average change in TOP-J total score (calculated by subtracting Time 1 from Time 2 score) was −0.08 (SD=2.9), with 21 participants showing mild improvement, 20 showing mild decline, and 9 showing no change. Additionally, the 21 participants who manifested improved scores were evenly distributed across diagnostic groups: 6 HCs, 6 CCs, 5 MCIs, and 3 ADs; χ2(3, n=50)=0.64, ns. Thus, results did not reveal practice effects over a 4-month time interval.

Validity

Internal consistency using confirmatory factor analysis

All factor analysis models were run using Mplus, employing the weighted least squares with mean and variance (WLSMV) estimator applied to the polychoric correlation matrix, as appropriate for the ordered categorical nature of these items. Criteria for goodness of fit included comparative fit index (CFI) >.95 and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) >.95. For the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), values <.08 indicated adequate fit, and <.05 indicated good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1998). We initially fit the data to a single-factor model including all 15 items. The single-factor model fit the data surprisingly well, with χ2(41)=48.59, p=.19; CFI was .961; TLI was .963; and RMSEA was .037. Standardized loadings of each of the items on the general factor are shown in Table 5. Item 5 (social/ethical) had a negative loading on the common factor, while 5 other items had relatively low loadings, including Items 9 (safety), 10 (social/ethical), 11 (safety), 13 (medical), and 14 (social/ethical). We thus excluded those 6 items and ran the single-factor model with the remaining 9 items. This model also fit the data well, with χ2(19)=27.885, p=.09; CFI was .956; TLI was .956; and RMSEA was .060. Standardized loadings of each of the items on the general factor are shown in Table 5. Notably, we present standardized loadings (not correlation coefficients); therefore, as the standard deviation of an item changes by 1 unit level, the level of the general factor correspondingly changes by more than 1 standard deviation unit. Removing items with low values had a negligible impact on the loadings of the 9 remaining items. All subsequent study analyses were conducted using the 9-item TOP-J version.

TABLE 5.

TOP-J loadings on a general factor defined by individual TOP-J items

| Item | Content domain | Loading on general factor 15-item model | 9-item model |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medical | 0.63 | 0.62 |

| 2 | Financial | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| 3 | Safety | 1.00 | 1.10 |

| 4 | Financial | 0.59 | 0.60 |

| 5 | Social/ethical | −0.04 | n/a |

| 6 | Medical | 0.69 | 0.68 |

| 7 | Safety | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| 8 | Social/ethical | 0.40 | 0.37 |

| 9 | Safety | 0.27 | n/a |

| 10 | Social/ethical | 0.32 | n/a |

| 11 | Safety | 0.27 | n/a |

| 12 | Social/ethical | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| 13 | Medical | 0.23 | n/a |

| 14 | Social/ethical | 0.28 | n/a |

| 15 | Financial | 0.52 | 0.49 |

Note. Items presented above are numbered according to their placement on the original 15-item TOP-J protocol. Items numbered 6, 7, 8, 12, and 15 were subsequently reordered as 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 on the final 9-item version. Values represent standardized loadings, not correlation coefficients.

Evidence for convergent and discriminant validity

We examined associations between the TOP-J and presumably related and unrelated measures. It is worth noting that this process posed a challenge given that, as a presumed measure of executive functioning, the TOP-J was likely to show varying degrees of relation with most other cognitive domains. Comparison of the TOP-J and an existing judgment test, the NCSE JQ, indicated a weak but statistically signification correlation (r=.22, p < .05). We also examined associations with specific neuropsychological tests with which the TOP-J theoretically should correlate strongly (e.g., executive functioning, language) or less strongly (e.g., visuoconstruction, emotional functioning). Table 6 presents results of these correlational analyses; sample sizes vary because a subset of AD participants did not complete all measures. In the entire sample, there were moderate correlations between performance on the TOP-J and scores on select measures of executive functioning, expressive language, verbal memory, and general fund of information, range r=.39 to r=.52. No significant correlations emerged between the TOP-J and select tests of simple auditory and visual attention, visual scanning, visuoconstruction, and depressive symptoms, range r=.09 to .15. We also compared the convergent and discriminant correlation coefficients (presented in Table 6) to determine whether they were reliably different from each other (Hinkle, Wiersma, & Jurs, 1988; http://www.medcalc.be/). The resulting z-statistics ranged from 2.52 to 3.76, and all corresponding p values were less than .05. Collectively, these analyses provide preliminary evidence of convergent and discriminant validity for the TOP-J.

TABLE 6.

Correlations between TOP-J and selected neuropsychological measures

| n | Correlation with TOP-J | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convergent validity | |||

| NCSE JQ | 132 | .22 | .05 |

| WCST, number of perseverative errors | 124 | −.43 | <.001 |

| DRS-2 Initiation/Perseveration | 125 | .47 | <.001 |

| DKEFS Phonemic Fluency | 125 | .40 | <.001 |

| Boston Naming Test | 124 | .51 | <.001 |

| CVLT-II: Immediate, Delay Recall | 126 | .41, .39 | <.001 |

| WAIS-III Information | 121 | .52 | <.001 |

| Discriminant validity | |||

| DRS-2 Attention | 125 | .09 | ns |

| DRS-2 Visuoconstruction | 125 | .14 | ns |

| DKEFS Visual Scanning Test | 122 | −.15 | ns |

| GDS, adjusted score | 130 | −.11 | ns |

Note. Total raw scores were utilized for all correlational analyses. NCSE JQ=Judgment Questionnaire subtest of the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Exam. WCST=Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. DRS=Dementia Rating Scale. DKEFS=Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System. CVLT-II=California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition. WAIS-III=Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition. GDS=Geriatric Depression Scale.

Evidence for criterion-related validity

Group differences and distribution characteristics

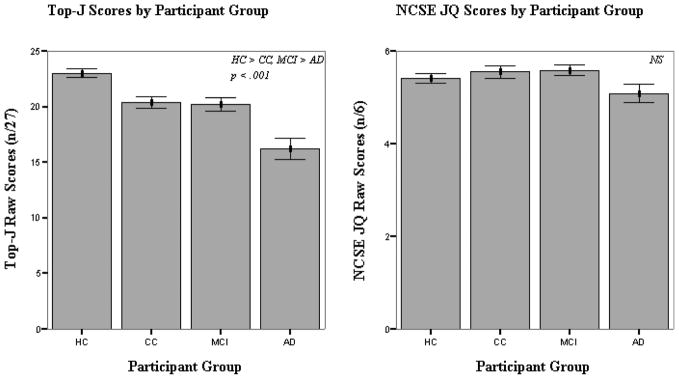

Degrees of asymmetry and peakedness in the distribution were evaluated by calculating skew and kurtosis statistics, applying cutoff values recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (1996). TOP-J scores were normally distributed for the CC, MCI, and AD groups (skewness=0.05, −0.38, −0.57; kurtosis=−0.59, −0.18, −0.64). Statistically significant negative skew was observed in the HC group, however, indicating a slight ceiling effect in cognitively intact older adults (skewness=−0.81; kurtosis=0.40). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate group differences in TOP-J total scores (see Table 7 and Figure 1). Results were statistically significant, F(3, 130)=20.64, p < .001, revealing the overall effect of diagnostic group membership. Due to the nonnormal distribution of TOP-J scores in the HCs, group differences also were evaluated using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallace H Test, with no change in findings. Post hoc comparisons using Bonferroni correction indicated that HCs obtained higher scores than CC, MCI, and AD participants, while ADs obtained lower scores than HC, CC, and MCI participants (approximately 2 SDs below the mean of HCs). CC and MCI participants showed an intermediate level of performance (approximately 1 SD below the mean score of HCs).

TABLE 7.

TOP-J and NCSE JQ performance by group

| Instrument | HC | CC | MCI | AD | p | Effect sizea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOP-J (n=134) | 23.0 (2.4) | 20.4 (3.1) | 20.2 (3.4) | 16.2 (4.8) | .000b | .33 |

| NCSE JQ (n=132) | 5.4 (0.68) | 5.5 (0.74) | 5.5 (0.71) | 5.1 (0.93) | ns | .06 |

Note. Data are mean (SD); TOP-J (n/27), NCSE JQ (n/6). TOP-J=Test of Practical Judgment. NCSE JQ=Judgment Questionnaire subtest of the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Exam. HC=healthy control. CC=cognitive complaints. MCI=mild cognitive impairment. AD=Alzheimer’s disease.

Partial eta squared.

HC > CC, MCI > AD.

Figure 1.

TOP-J and NCSE JQ scores by participant group.

One-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) also was used to evaluate mean differences across groups. Age, gender, and education did not account for a significant amount of the variance between groups (p > .05). Further correlational analyses revealed that TOP-J performance was not significantly correlated with age, r(131)=−.15, ns, gender, r(131)=.01, ns, or depressive symptoms endorsed on the GDS, r(130)=−.11, ns. However, TOP-J score showed a statistically significant association with level of education, r(130)=.28, p=.001. ANOVA also was used to evaluate mean group differences in NCSE JQ score. Participants were administered the last 3 NCSE JQ items, and each item was scored on a scale of 0 to 2 (creating a total score that ranged from 0 to 6). The groups did not differ significantly on the NCSE JQ. Due to the nonnormal distribution of NCSE JQ scores (skewness=−1.5; kurtosis=2.0), group differences also were evaluated using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallace H Test, with no change in findings.

Relation to informant report of functioning

In order to explore the relation between TOP-J performance and everyday functioning, we examined associations between TOP-J score and informant responses on a Neurobehavioral Function/Activities of Daily Living Scale (NBF/ADL, Saykin, 1992) in the patient groups. MCI and AD participants with available data (n=50) were combined for this analysis. Informants rated current level of ability on a 7-point scale ranging from above average (score=1) to severe disability (score=7). Total score on the NBF/ADL measure was derived by summing responses to the 7 items most closely related to TOP-J content including: decision making, reasoning through complicated problems, awareness of danger, judgment in potentially dangerous situations, managing money (e.g., paying bills, balancing checkbook), making purchases, and managing medications. Results revealed a statistically significant, moderate association between informant NBF/ADL and TOP-J total scores, r(50)=−.43, p=.002.

DISCUSSION

We report on the development and initial validation of a brief, objective measure of everyday judgment suitable for use with older adults. Our approach relied primarily on a rational-empirical method, in which practical and theoretical considerations served as the basis for test development, and empirical methods served as the basis for evaluation of item and scale qualities. Item development involved review of the literature related to clinical assessment of judgment and related executive processes (e.g., everyday decision making, social problem solving), survey of neuropsychology colleagues regarding what constitutes lapses in judgment, and examination of relevant participant and informant data from our Memory and Aging Study. We strove to develop stimuli that were representative of the types of judgment problem regularly faced by older adults. Another goal was to create scenarios that were easily understood, yet complex enough to require active problem solving and higher order cognitive abilities. The TOP-J employs an open-ended format in which participants listen to brief scenarios of everyday problems and report aloud their proposed solutions, which are recorded verbatim; unclear or ambiguous responses are queried in a neutral manner.

The initial TOP-J protocol contained 15 items, and it was possible to fit a single-factor model to all items. Unfortunately, the loading for 1 item was close to zero, and 4 other items had relatively modest loadings. Further analyses indicated that a single-factor model with 9 items fitted the data well, and loadings for all of the items were greater than .30, a guideline McDonald (1999) endorses for salience in this context. The final TOP-J contained 9 items, all of which relate to important safety, medical, social/ethical, and financial concerns.2 A survey of practicing neuropsychologists confirmed that formal assessment of everyday judgment ability should incorporate issues related to the identified content domains (Borgos et al., 2006b). Given the limited number of questions and overlap of content domains for many of the test items, it was not possible to identify a four-domain measure using factor analytical techniques. Therefore, the recommended practice is to sum all TOP-J items into a single overall composite score rather than dividing the test into subscales. Individual responses earn 0, 1, 2, or 3 points (maximum score=27), with higher scores indicating better judgment. Detailed examiner instructions are included on the protocol, and the test takes approximately 10 minutes to administer and score.

The TOP-J demonstrated strong interrater agreement (r=.95) and temporal stability over a 4-month interval (r=.78). Internal consistency was adequate (r=.63) in a sample of 134 elderly individuals with varying degrees of cognitive decline. These reliability and internal consistency properties exceed those of existing judgment tests (i.e., NCSE JQ and NAB JDG). As the construct of executive functioning is thought to direct all cognitive activity and behavior to some degree (Gioia, Isquith, & Guy, 2001), few cognitive instruments would be expected to have little or no association with the TOP-J. Nonetheless, evidence for convergent validity was demonstrated by moderate correlations with theoretically related constructs (e.g., tests of executive functioning, language, and memory), whereas discriminant validity was demonstrated by low correlations with measures involving minimal executive demands (e.g., rote attention, visuoconstruction, and emotional functioning).

Another study goal was to investigate the TOP-J’s ability to detect group differences in older adults with varying degrees of decline. As noted by Marsiske and Margrett (2006), the ability to use everyday problem-solving measures to identify subtle preclinical neurodegenerative change is an important issue requiring further study. Results indicated that the mild AD patients scored approximately 2 standard deviations below the mean of HCs on the TOP-J (clinically impaired range). A related goal was to determine whether judgment is compromised in preclinical disease stages. Although episodic memory impairment is the hallmark feature of MCI, research has revealed mild declines in executive functioning as well (Crowell et al., 2002; Davie et al., 2004; Rabin et al., 2006; Ready, Ott, Grace, & Cahn-Weiner, 2003). The MCI group showed an intermediate level of performance relative to the HC and AD groups. While significantly lower than the HCs, however, MCI patients generally scored within normal limits clinically (i.e., approximately 1 SD below the HC mean, low average range). The CC group showed the same pattern of findings, also scoring approximately 1 standard deviation below the mean of HCs. Cognitive complaints in otherwise healthy older adults are common but their clinical significance is controversial, with some research suggesting that such complaints may be a harbinger of dementia. Overall, our findings indicated a relative weakness in judgment ability in both MCI and CC and suggest the need for further investigation of the temporal course of declining judgment skills from probable preclinical to clinical stages of dementia. This research may have important implications for early detection and remediation.

Study limitations and directions for future research

While the TOP-J may be sensitive to the influence of nonneurologic demographic factors such as education and cultural background, we were unable to explore such factors systematically in the current study given the relatively homogenous ethnic and educational composition of our participants. Future research will sample from a broader demographic range with the goals of replicating the current findings and establishing improved TOP-J norms and cutoff scores. We also will investigate whether some of the TOP-J items have differential item function related to education or intelligence (Camilli & Shepard, 1994; Holland & Wainer, 1993). We employed strict criteria for entry into our Memory and Aging Study such as the exclusion of individuals with significant medical, psychiatric, or neurological conditions other than AD or amnestic MCI. In future research, we plan to assess additional MCI subtypes (e.g., multiple domain, single nonmemory domain), as these individuals often present with complaints of executive dysfunction. A related goal is to use the TOP-J with other clinical groups with presumed compromised judgment including frontal-subcortical dementias, stroke, and traumatic brain injury. We recently utilized the TOP-J in a sample of adults with mixed neuropsychiatric conditions (Borgos et al., 2006a), and preliminary results indicated that patients exhibited difficulty with practical judgment relative to controls. Additionally, the TOP-J was well tolerated and understood by this group of participants who presented with lower levels of education and estimated baseline intellect than did our older adult cohort. It is worth noting that in the current study our initial 45 participants were administered the TOP-J by telephone. These participants reported no difficulty hearing or understanding test questions and performed at a level equivalent to the larger sample. In future research, however, we will use a single mode of administration to maximize consistency in assessment methods.

The judgment scenarios developed for this instrument were based on hypothetical situations, and while many participants spontaneously mentioned having experienced similar problems, it is uncertain how they would actually behave in the real world. It would be desirable but extremely difficult to probe the actual execution of judgment responses outside formal assessment settings. Future research, however, will attempt to correlate TOP-J performance with real-world outcomes such as high-level activities of daily living. The associations already observed between the TOP-J and items from an informant ADL scale represent a starting point for this effort, and we are working to develop an informant rating scale specifically focused on judgment ability. We also plan to incorporate other commonly used tests that are related to the construct of judgment into our existing battery (e.g., WAIS-III Comprehension) and to examine relations between those instruments and the TOP-J. Another potential direction for research involves altering the administration procedures to allow for multiple responses for each question posed. This would enable investigation of solution fluency in addition to solution efficacy and might yield valuable information about participants’ cognitive processes during active problem solving (Marsiske & Margrett, 2006).

As with any assessment tool, it is essential to consider TOP-J results in the context of other information about judgment such as collateral reports or examiner observations. Clinicians and researchers should not place too much interpretive significance on individual items, due to the lower reliability of such items relative to the entire scale. Careful review of individual items in the context of the assessment tool as a whole, however, may uncover specific circumstances or cognitive processes that contribute to poor judgment. For example, some patients may show an impaired ability to organize information while others may have trouble generating solutions, initiating a response, or filtering out irrelevant data to arrive at a satisfactory solution. Finally, it is important to note that the TOP-J is not meant to serve as a global severity marker for the dementing process. While very poor scores certainly suggest impaired judgment, some individuals with AD will score within the expected range of functioning, especially early in the disease process.

CONCLUSION

Judgment in everyday situations is an important aspect of cognition that warrants formal assessment during neuropsychological evaluations of older adults. Knowledge gained from this process can be used for diagnostic purposes and to address issues related to functional competence and required level of present and future care. Despite the significance of this cognitive domain, few objective tests of judgment have been developed, and those currently in use are limited with regard to psychometric properties, content validity, and/or clinical utility. This study reported on the development of a psychometrically sound and clinically useful measure of judgment that is easy to administer, score, and interpret. The TOP-J shows promise for reliable assessment of judgment that can be included in comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations. Future research utilizing the TOP-J has the potential to enhance general clinical knowledge and practice approaches to the assessment of judgment in older adults in varying stages of cognitive impairment. Longitudinal assessments are being performed to examine predictive validity of the TOP-J for cognitive progression in AD, MCI, and other clinical groups. Additional goals include the collection of more demographically-diverse normative data, development of an alternative test form, and determination of cutoff scores for our clinical groups. We also plan to examine relations with neuroimaging data to investigate the neural basis for impaired judgment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Howard Cleavinger, Robert Santulli, Gwen Sprehn, Robert Roth, Peter Isquith, Nadia Pare, and Brenna McDonald, as well as Harris Rabin, Heather Pixley, Paul Wang, John West, and Mark Root for their contributions with various aspects of this project. This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Aging (R01 AG19771, K08 022232), Alzheimer’s Association, National Science Foundation, and Ira DeCamp Foundation.

APPENDIX A

Assessment battery

Neuropsychological assessment

Action Fluency Task (Piatt, Fields, Paolo, & Troster, 1999)

American National Adult Reading Test (ANART; Grober, Sliwinski, Schwartz, & Saffran, 1989)

Barona algorithm (Barona, Reynolds, & Chastain, 1984)

Boston Naming Test (BNT; Goodglass, Reynolds, & Chastain, 2001)

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions–Adult Version (BRIEF-A; Roth, Isquith, & Gioia, 2005)

California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition (CVLT-II; Delis et al., 2000)

Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFS, Verbal Fluency, Trail Making Test; Delis & Kaplan, 2001)

Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, Second Edition (DRS-2; Jurica et al., 2001)

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975)

Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI; Cummings et al., 1994)

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition (WAIS-III, Information, Block Design, Digit Span, Digit Symbol, Vocabulary; Wechsler, 1997)

Wechsler Memory Scale, Third Edition (WMS-III, LMI & LMII; VRI & VRII; Psychological Corporation, 1997)

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST, short form; Heaton et al., 1993)

Cognitive complaint index

Neurobehavioral Function and Activities of Daily Living Scale (self- and informant versions; Saykin, 1992)

Geriatric Depression Scale, four cognitive items (GDS; Yesavage et al., 1982)

Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (self- and informant versions; Jorm, Scott, & Jacomb, 1989)

Memory Assessment Questionnaire (Santulli et al., 2005)

Memory Self-Rating Questionnaire (Squire, Wetzel, & Slater, 1979)

Memory and Aging Telephone Screen, 10 cognitive items (Rabin et al., 2004)

APPENDIX B

Sample TOP-J items and scoring criteria

Administration notes

(Q) indicates that examiner should query the examinee with the statement “Tell me more about that” or “Explain what you mean.” Additional information (*in italics) can be provided if the participant directly requests this information or gives a response that contradicts this information. More extensive scoring criteria are provided on the actual TOP-J protocol.

Sample Item 1

You are vacationing far from home and realize you don’t have enough blood pressure pills for the entire trip. What would you do?

-

3

contact physician (or insurance company) and have prescrip called/faxed into local pharmacy/ call home, have pills Fedexed/call local pharmacy or doctor (Q) – (and have them call in prescrip)/call local WALMART/CVS, etc. since they have your prescrip records on computer

-

2

visit local doctor/ER/hospital at vacation site and ask for prescription or describe problem/ take pills to local pharmacy, see if they can help/(*you don’t have prescription with you)/ have doc or pharmacy send free samples or prescription/get pharmacy to give you enough pills to make it

-

1

take smaller doses to make it last longer/ration them/vague response even after query (e.g., “go to pharmacy & get some,” “call home & ask for help,” “have pharmacist mail them” “get some”)

-

0

wait to see if you need them, no reason to worry in advance/nothing, wait until you get home/wait until something bad happens/don’t know, go without/avoid strenuous activity

Sample Item 2

You read a report that the government will reduce monthly social security payments from $1,000 to $500 for a certain percentage of recipients. What would you do?

-

3

find out how likely it is your benefits will be reduced/call to gather more info in attempt to determine if it affects you/call SS office to find out more (Q) – if you are affected

-

2

vague attempt at getting more info without directly trying to determine if you are affected or assumption that you are affected (e.g., “look into it because it’s not right” “determine validity of info” “call & see what I can do (Q)”)/call Senator to get info (Q)/ research issue or “find out why” (without determining if benefits will change)/research how much reduction will be

-

1

reduce monthly spending/get bills paid so you can budget $ more closely/go to work/borrow cash/adjust finances

-

0

do nothing/wait to see what happens/this doesn’t affect me/you can’t fight gov (Q)/tell gov it’s a bad idea/complain or call local papers/don’t believe it/just live on my resources/write my senator/congressman and complain/be mad

Footnotes

NINCDS-ADRDA refers to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association.

While factor analytic findings supported the 9-item TOP-J, clinicians and researchers may opt to use the original 15-item version, which also showed good psychometric properties, and which may provide additional information about patients’ judgment ability. The 9- and 15-item TOP-J protocols are both available upon request from the corresponding author.

Portions of this research project were presented at the 33rd annual International Neuropsychological Society conference in February 2005.

References

- Allaire JC, Marsiske M. Everyday cognition: Age and intellectual ability correlates. Psychology and Aging. 1999;14:627–644. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.4.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barona A, Reynolds C, Chastain R. A demographically based index of premorbid intelligence for the WAIS–R. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:885–887. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand RM, Willis SL. Everyday problem solving in Alzheimer’s patients: A comparison of subjective and objective assessments. Aging & Mental Health. 1999;3:281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields F, Stein R, Watson TL. Age differences in emotion-regulation strategies in handling everyday problems. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2004;59B:P261–P269. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.p261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgos MJ, Rabin LA, Koven NC, Roth RM, Flashman LA, Saykin AJ. Assessment of practical judgment in a mixed neuropsychiatric sample using the TOP-J [Abstract]. Proceedings of the 34th Annual Meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society; 2006a. p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Borgos MJ, Rabin LA, Pixley HS, Saykin AJ. Practices and perspectives regarding the assessment of judgment skills: A survey of clinical neuropsychologists [Abstract]. Proceedings of the 34th Annual Meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society; 2006b. p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Camilli G, Shepard LA. Methods for identifying biased test items. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Channon S. Frontal lobe dysfunction and everyday problem-solving: Social and non-social contributions. Acta Psychologica. 2004;115:235–254. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channon S, Crawford S. Problem-solving in real-life-type situations: The effects of anterior and posterior lesions on performance. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:757–770. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius SW, Caspi A. Everyday problem solving in adulthood and old age. Psychology and Aging. 1987;2:144–153. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.2.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell TA, Luis CA, Vanderploeg RD, Schinka JA, Mullan M. Memory patterns and executive functioning in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2002;9:288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie JE, Azuma T, Goldinger SD, Connor DJ, Sabbagh MN, Silverberg NB. Sensitivity to expectancy violations in healthy aging and mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:269–275. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis D, Kaplan E. Delis–Kaplan Executive Function Battery. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. The California Verbal Learning Test. 2. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2000. Adult version manual. [Google Scholar]

- Denney NW, Pearce KA. A developmental study of practical problem solving in adults. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4:438–442. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drane DL, Osato SS. Using the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination as a screening measure for older adults. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1997;12:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke LM, Kaszniak AW. Executive control functions in degenerative dementias: A comparative review. Neuropsychology Review. 2000;10:75–99. doi: 10.1023/a:1009096603879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitten LJ, Lusky R, Hamann C. Assessing treatment decision-making capacity in elderly nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1990;38:1097–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC. Assessment of executive functions in children with neurological impairment. In: Simeonsson RJ, Rosenthal SL, editors. Psychological and developmental assessment: Children with disabilities and chronic conditions. New York: The Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, Kaplan E, Barresi B. Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCat-T: A clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:1415–1420. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.11.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Sliwinski M, Schwartz M, Saffran E. Unpublished manuscript. 1989. The American version of the NART for predicting premorbid intelligence. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test manual: Revised and expanded. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle DE, Wiersma W, Jurs SG. Applied statistics for the behavioral sciences. 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Holland PW, Wainer H, editors. Differential item functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Scott R, Jacomb PA. Assessment of cognitive decline in dementia and by informant questionnaire. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1989;4:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jurica P, Leitten C, Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale–2. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kajanne A. Structure and content: The relationship between reflective judgment and laypeople’s viewpoints. Journal of Adult Development. 2003;10:173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Karlawish JHT, Casarett DJ, James BD, Xie SX, Kim SYH. The ability of persons with Alzheimer disease (AD) to make a decision about taking an AD treatment. Neurology. 2005;64:1514–1519. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000160000.01742.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SYH, Karlawish JHT, Caine ED. Current state of research on decision-making competence of cognitively impaired elderly persons. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10:151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, Chui H, Corey-Bloom J, Relkin N, et al. Practice parameter: Diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review): Report on the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56:1143–1153. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFleche G, Albert MS. Executive function deficits in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 1995;9:313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein D, Amigo E, Duara R, Guterman A, Hurwitz D, Berkowitz N, et al. A new scale for the assessment of functional status in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1989;44:114–121. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.4.p114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiske M, Margrett JA. Everyday problem solving and decision making. In: Birren JE, Warner Schaie K, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 6. New York: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 315–342. [Google Scholar]

- Marson D, Harrell L. Executive dysfunction and loss of capacity to consent to medical treatment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 1999;4:41–49. doi: 10.1053/SCNP00400041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson DC, Hawkins L, McInturff B, Harrell LE. Cognitive models that predict physician judgments of capacity to consent in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1997;45:458–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson DC, Schmitt FA, Ingram KK, Harrell LE. Determining the competency of Alzheimer patients to consent to treatment and research. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 1994;8(Suppl 4):5–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP. Test theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus (Version 3) [Computer program] Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Northern California Neurobehavioral Group, Inc. Manual for The Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Exam. Fairfax, CA: Author; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs R, Morris JC, Rabins PV, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Archives of Neurology. 2001a;58:1985–1992. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice parameter: Early detection of dementia: Mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001b;56:1133–1142. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatt AL, Fields JA, Paolo AM, Troster AI. Action (verb naming) fluency as an executive function measure: Convergent and divergent evidence of validity. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:1499–1503. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Corporation. Wechsler Memory Scale. 3. San Antonio, TX: Author; 1997. WMS-III technical manual. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin LA, Roth RM, Isquith, Wishart HA, Nutter-Upham KE, Pare N, et al. Self-and informant reports of executive functions on the BRIEF-A in MCI and older adults with cognitive complaints. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2006;21:721–732. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin LA, Saykin AJ, Wishart HA, Flashman LA, Wang PJ, Nutter-Upham KE, et al. Telephone-based screening for MCI and cognitive complaints: Preliminary validation by comprehensive assessment. Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society Meeting; 2004. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ready RE, Ott BR, Grace J, Cahn-Weiner DA. Apathy and executive dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11:222–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth RM, Isquith PK, Gioia GA. BRIEF-A: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions–Adult Version. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Santos JRA. Cronbach’s alpha: A tool for assessing the reliability of scales. Journal of Extension. 1999:37. Retrieved April 21, 2006, from http://joe.org/joe/1999april/tt3.html.

- Santulli RB, Saykin AJ, Rabin LA, Wishart HA, Flashman LA, Pare N, et al. Differential sensitivity of cognitive complaints associated with amnestic MCI: Analysis of patient and informant reports. Presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference on Prevention of Dementia; Washington, DC. 2005. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ. Neurobehavioral Function and Activities of Daily Living Rating Scale. A. J. Saykin, Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth Medical School One Medical Center Drive; Lebanon, NH 03756, USA: 1992. (NBFADL–63 item version) [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Wishart HA, Rabin LA, Santulli RB, Flashman LA, West JD, et al. Older adults with cognitive complaints show brain atrophy similar to that of amnestic MCI. Neurology. 2006;67:834–842. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234032.77541.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Wetzel CD, Slater PC. Memory complaints after electroconvulsive therapy: Assessment with a new self-rating instrument. Biological Psychiatry. 1979;14:791–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern RA, White T. Neuropsychological Assessment Battery: Administration, scoring, and interpretation manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 3. New York: Harper Collins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton WJL, Dumke HA. Age differences in everyday problem-solving and decision-making: A meta-analytic review. Psychology & Aging. 2005;20:85–99. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellinga A, Smit JH, van Leeuwen E, van Tilburg W, Jonker C. Competence to consent to treatment of geriatric patients: Judgments of physicians, family members, and the vignette method. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;19:645–654. doi: 10.1002/gps.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- White T, Stern RA. Neuropsychological Assessment Battery: Psychometric and technical manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Willis SL. Test manual for the Everyday Problems Test for Cognitively Challenged Elderly. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Willis SL. Everyday cognitive competence in elderly persons: Conceptual issues and empirical findings. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:595–601. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis SL, Allen-Burge R, Dolan MM, Bertrand RM, Yesavage J, Taylor JL. Everyday problem solving among individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. The Gerontologist. 1998;38:569–577. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis SL, Marsiske M. Manual for the Everyday Problems Test. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, et al. Mild cognitive impairment—beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DC, Patterson MB, Whitehouse PJ. Utility of the Judgment Questionnaire subtest of the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination in the evaluation of individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease. Clinical Gerontologist. 2000;21:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]