Abstract

A Gouy-Chapman-Stern model has been developed for the computation of surface electrical potential (ψ0) of plant cell membranes in response to ionic solutes. The present model is a modification of an earlier version developed to compute the sorption of ions by wheat (Triticum aestivum L. cv Scout 66) root plasma membranes. A single set of model parameters generates values for ψ0 that correlate highly with published ζ potentials of protoplasts and plasma membrane vesicles from diverse plant sources. The model assumes ion binding to a negatively charged site (R− = 0.3074 μmol m−2) and to a neutral site (P0 = 2.4 μmol m−2) according to the reactions R− + IΖ ⇌ RIΖ−1 and P0 + IΖ ⇌ PIΖ, where IΖ represents an ion of charge Ζ. Binding constants for the negative site are 21,500 m−1 for H+, 20,000 m−1 for Al3+, 2,200 m−1 for La3+, 30 m−1 for Ca2+ and Mg2+, and 1 m−1 for Na+ and K+. Binding constants for the neutral site are 1/180 the value for binding to the negative site. Ion activities at the membrane surface, computed on the basis of ψ0, appear to determine many aspects of plant-mineral interactions, including mineral nutrition and the induction and alleviation of mineral toxicities, according to previous and ongoing studies. A computer program with instructions for the computation of ψ0, ion binding, ion concentrations, and ion activities at membrane surfaces may be requested from the authors.

PM electrical phenomena play an important role in plant physiology, especially plant-mineral interactions. Two global electrical properties of the PM are commonly recognized. The first is ψm, which may be measured relatively easily by the insertion of a microelectrode into cells in situ (Nobel, 1991). ψm is responsive to many factors, including the composition of the bathing medium, the activity of ion pumps, and the state of ion channels, which are themselves responsive to ψm (Hille, 1992). ψm is usually described in introductory plant physiology textbooks and in general treatments of plant-mineral interactions (Marschner, 1995).

The second global electrical feature of the PM is ψ0, the measurement of which is more difficult than the measurement of ψm. The procedure entails the preparation of protoplasts or PM vesicles whose electrophoretic mobility is then measured to obtain a ζ potential (for refs., see Table I), which reflects the electrical potential at the hydrodynamic plane of shear at a small distance from the PM surface (McLaughlin, 1989; Morel and Hering, 1993). Consequently, the ζ potential has a somewhat lower magnitude than the ψ0. Only a few ζ potential measurements have been reported for the plant PM (for refs., see Table I), and ψ0 is rarely mentioned in introductory plant physiology textbooks or in general treatments of plant-mineral interactions.

Table I.

Published ζ potentials of plant protoplasts or PM vesicles in various media compared with calculated surface potentials

| Species and Ref. | Solution No. | pH | CaCl2 | MgSO4 | NaCl | KCl | LaCl3 | ζ Potential | ψ0,Y | ψ0,A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mV | |||||||||

| Barley leaf protoplasts (Abe and Takeda, 1988) | ||||||||||

| 1 | 6.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | −48 | −66 | −65 | ||||

| 2 | 6.7 | 0.1 | 6.5 | −39 | −59 | −58 | ||||

| 3 | 6.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 6.0 | −39 | −59 | −58 | |||

| 4 | 6.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | −17 | −7 | −6 | |||

| 5 | 6.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0 | +2 | +3 | |||

| 6 | 6.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | +14 | +12 | +13 | |||

| 7 | 3.6 | 0.1 | 6 | −2 | −14 | +5 | ||||

| 8 | 3.6 | 0.1 | 1 | +23 | +10 | +17 | ||||

| Barley leaf protoplasts (Obi et al., 1989a) | ||||||||||

| 9 | 7.6 | 3 | −29 | −100 | −100 | |||||

| 10 | 7.6 | 7.5 | −20 | −82 | −82 | |||||

| 11 | 7.6 | 15 | −13 | −67 | −66 | |||||

| 12 | 7.6 | 1 | 14 | −13 | −67 | −66 | ||||

| 13 | 7.6 | 30 | −10 | −52 | −51 | |||||

| 14 | 7.6 | 1 | 4.5 | −10 | −36 | −36 | ||||

| 15 | 7.6 | 1a | 4.5 | −11 | −36 | −36 | ||||

| 16 | 7.2 | 0.5 | 0.17 | 0 | −2 | −2 | ||||

| 17 | 6.5 | 5 | 1 | +3 | +12 | +12 | ||||

| Corn root PM vesicles (Gibrat et al., 1985) | ||||||||||

| 18 | 6.5 | 15 | −24 | −64 | −64 | |||||

| 19 | 6.5 | 65 | −14 | −36 | −36 | |||||

| 20 | 6.5 | 6 | 15 | −8 | −16 | −15 | ||||

| 21 | 6.5 | 6 | 65 | −6 | −13 | −12 | ||||

| Tobacco leaf protoplasts (Nagata and Melchers, 1978) | ||||||||||

| 22 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 10 | −28 | −56 | −55 | ||||

| 23 | 5.8 | 1 | 6.7 | 10 | −25 | −32 | −32 | |||

| 24 | 5.8 | 10 | 6.7 | 10 | −9 | −10 | −9 | |||

| 25 | 5.8 | 100 | 6.7 | 10 | 0 | +7 | +8 | |||

| Rauwolfia serpentina cultured cell protoplasts (Obi et al., 1989b) | ||||||||||

| 26 | 7.3 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | −18 | −72 | −71 | |||

| 27 | 6.3 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | −18 | −69 | −69 | |||

| 28 | 5.3 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | −17 | −56 | −54 | |||

| 29 | 4.2 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | −12 | −27 | −18 | |||

| 30 | 3.0 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | +2 | −5 | +29 | |||

| Barley leaf protoplasts (Obi et al., 1990) | ||||||||||

| 31 | 7.3 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | −18 | −72 | −71 | |||

| 32 | 6.3 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | −16 | −69 | −69 | |||

| 33 | 5.2 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | −12 | −54 | −51 | |||

| 34 | 4.0 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | +1 | −22 | −10 | |||

| 35 | 2.7 | 0.02 | 6 | 1 | +18 | −2 | +40 | |||

ψ0,Y is the potential computed by the model of Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) and ψ0,A is the potential computed by the adjusted model of the present study. For each of the two models, a single set of parameter values was used throughout. The column designated NaCl includes NaCl plus any monovalent buffer ions.

MgCl2.

Both ψm and ψ0 are physiologically important because electrical potential gradients influence the distribution of ions. ψ0 is often sufficiently negative to enrich the concentration of cations or to deplete the concentration of anions at the PM surface by more than 10-fold relative to the bathing medium (Barber, 1980). ψ0 is influenced by the composition of the medium. High ionic strength reduces the negativity of ψ0, and some ions can convert ψ0 to positive values (Table I). The common neglect of ψ0 is inconsistent with its importance, so the neglect probably reflects the difficulty of measuring ψ0 and the absence of verified model parameters for its computation in biological membranes. Nevertheless, investigators have considered physiological phenomena in terms of ψ0 (Barber, 1980; Theuvenet and Borst-Pauwels, 1983; Gibrat et al., 1985, 1989; Abe and Takeda, 1988; Wagatsuma and Akiba, 1989; Suhayda et al., 1990; Kinraide et al., 1992; Kinraide, 1994, 1998; Yermiyahu et al., 1997a, 1997b, 1997c; for references to the animal literature, see McLaughlin, 1989; Hille, 1992; for extensive references and tabulations of relevant data, including constants for the binding of ions to artificial and biological membranes, see Tatulian, 1998).

The objective of the present study was to determine the suitability of a computational approach to the estimation of ψ0 for the PM from diverse plant sources. In particular, the study assesses the suitability of a Gouy-Chapman-Stern model using a single set of model parameters derived principally by Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) for the computation of ψ0 in response to ionic solutes. Additionally, our goal was to make available an easy-to-use computer program for the computation of ψ0, ion binding, ion concentrations, and ion activities at plant PM surfaces. This program, together with a manual for its use, may be obtained from T.B.K. A more comprehensive program that integrates numerically the ion content of the diffuse layer from the membrane surface to any desired distance from the surface and that is suitable for the computation of total sorbed ions (ions bound and accumulated in the diffuse layer) may be obtained from G.R.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Gouy-Chapman-Stern Model

ζ potential measurements (Table I) were taken for PM vesicles or protoplasts, and the Gouy-Chapman-Stern model was applied to the PM of root cells as if the cell wall did not exist. This may be justified if the cell wall can be considered an independent phase interposed between the PM and the bulk-phase medium, achieving near ionic equilibrium with the medium and presenting an insignificant barrier to the flux of ions. Experimental justification for our treatment is provided by Gage et al. (1985, 1986), who compared ordinary yeast cells with cells that were plasmolyzed or enzymatically stripped of their walls. Rb+ uptake was dependent on the estimated ψ0 of the PM and on the intracellular [K+], not on the cell wall Donnan potential. Furthermore, the ψ0 of the PM did not appear to be influenced by the cell wall.

The Gouy-Chapman-Stern model may be expressed in a few equations (Lau et al., 1981; Kinraide, 1994; Nir et al., 1994; Yermiyahu et al., 1997c). The Gouy-Chapman portion of the model is expressed in the Müller equation (derivation presented by Barber [1980] and Tatulian [1998], the latter noting that the Müller equation has erroneously come to be known as the Grahame equation):

|

1 |

where ς is the charge density on the membrane surface expressed in coulombs per square meter (C m−2); 2εrεoRT = 0.00345 at 25°C for concentrations expressed in molarity (εr is the dielectric constant for water, ε0 is the permittivity of a vacuum, R is the gas constant, and T is temperature); [IΖ]∞ is the concentration of ion IΖ (the ith ion) in the bulk-phase medium; Ζi is the charge on ion IΖ; F is the Faraday constant; and ψ0 is the electrical potential at the membrane surface measured with respect to the bulk-phase medium a long way from the surface; −ΖiFψ0/RT = −Ζiψ0/25.7 at 25°C for ψ0 expressed in millivolts.

ς depends in part on ςintrinsic, the surface charge density in the absence of any bound solute ions. ς also includes those solute ions that bind to the membrane surface, and the Stern modification of the model takes this binding into account. The present model can accommodate 1:1 binding of ions to a negatively charged site (R−) and a neutral site (P0) as expressed in the following reactions:

|

2 |

and

|

3 |

Binding constants, specific for ion and site, may be expressed as:

|

4 |

and

|

5 |

where [R−], [P0], [RIΖ−1], and [PIΖ] denote membrane surface densities in moles per square meter (mol m−2), and [IΖ]0 denotes the concentration of the unbound ion at the membrane surface. [IΖ]0 may be computed from bulk-phase concentrations by the Boltzmann equation:

|

6 |

To compute ς, it is necessary to know [RT] (R− + Σi[RIΖ−1]) and [PT] (P0 + Σi[PIΖ]), which are the total surface densities of binding sites whether or not solute ions are bound. (ςintrinsic = [RT]F; multiplication by F is needed to convert units to coulombs per square meter.) It is also necessary to know the binding constants, KR,I and KP,I, and the concentrations of all of the ions in the bulk-phase medium. With that knowledge, the surface charge density of each membrane species (including R−, RIΖ−1, and PIΖ) can be computed from Equations 4, 5, and 6, contingent upon the value of ψ0, and appropriately summed:

|

7 |

Thus, trial values for ψ0 may be used to compute ς using Equations 1 and 7. When the values for ς converge, then the value of ψ0 will have been found. With that value, we assume that the Nernst equation may be used to compute surface activities of ions (the issue of the simultaneous validity of Eqs. 6 and 8 is discussed, but not resolved, by Kinraide [1994]):

|

8 |

Selection of Initial Values for the Model Parameters

To use the Gouy-Chapman-Stern model, values for the adjustable model parameters must be selected. To begin, we adopted the following values assumed or estimated by Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) for wheat (Triticum aestivum L. cv Scout 66) root PM: ςintrinsic = 29.7 mC m−2 (corresponding to [RT] = 0.3074 μmol m−2 or 540 Å2 intrinsic charge−1), KR,H = 21,500 m−1, KR,Al = 20,000 m−1, KR,La = 2,200 m−1, KR,Ca = KR,Mg = 30 m−1, KR,Na = KR,K = 1 m−1, and KR,anions = 0 (subscript Al refers to Al3+; AlOH2+ and Al(OH)2+ almost certainly have trivial electrical effects because of very low concentrations, but their binding constants were assumed to equal KR,Ca and KR,Na, respectively). The binding constants were based on literature values (K+ and Ca2+) and on the measured sorption of H+, Al3+, and La3+ (sorption refers to ions bound and accumulated in the diffuse layer). Values for [PT] and KP,I were not assigned because binding to neutral sites was not assumed. The estimation of ςintrinsic was based on the quenching of 9-aminoacridine fluorescence.

Selection of Published ζ Potentials

ζ potential measurements of the PM from several plant species and tissues were compiled from six publications (Table I). To be included, each publication had to present at least four measurements taken in solutions of variable solute compositions. For each solution, ψ0 was computed according to the model and parameter values of Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) and will henceforth be denoted ψ0,Y.

Improvement of the Model

The model was improved by altering adjustable parameters on the basis of two criteria. The first was the increase in the correlation:

|

9 |

for each of the six studies presented in Table I. (According to theory, Eq. 9 is approximate; a is expected to equal 0 because ζ potential = 0 when ψ0 = 0; b is a constant only if the ionic strength, the distance of the plane of shear from the PM surface, and the temperature are constant [see below]. b is expected to be <1 if ψ0 is accurately computed, and b may be even lower if the assumed value of ςintrinsic is too high or if there are other model deficiencies.)

The second criterion was the avoidance of a significant degradation of the very high correspondence between measured and computed ion sorption observed in the study by Yermiyahu et al. (1997c).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Correlations between Computed ψ0,Y and Published ζ Potentials

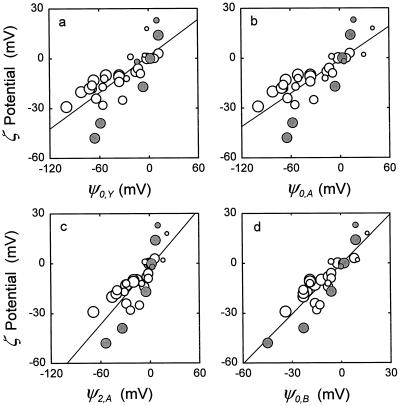

Figure 1a presents a plot of ζ potential versus ψ0,Y for all 35 points in Table I taken together. Table II presents statistics for regressions of the six individual studies. An examination of the data reveals the following points of interest.

Figure 1.

ζ potentials of plant protoplasts or PM vesicles plotted against calculated ψ0. ζ potentials are the published values presented in Table I. Symbol diameters are proportional to pH, and shaded symbols refer to the first study in Table I. a, ψ0,Y calculated by the Gouy-Chapman-Stern model presented by Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) in which ions bind only to negative sites. b, ψ0,A calculated by the same model, except that ions were also allowed to bind to neutral sites. c, ψ2,A calculated by the model of (b) for a region 2 nm from the PM surface. d, ψ0,B calculated using a model in which parameters were adjusted without reference to the model of Yermiyahuet et al. (1997c). The binding constantsB in Figure 4 are from this model for ψ0,B.

Table II.

Regression statistics for ζ potential compared with ψ0

r2 for ζ potential = a + bψ0, where ψ0 was computed by two models: ψ0,Y was computed according to the model presented by Yermiyahu et al. (1997c), and ψ0,A was computed according to the adjusted model of the present study. Each study is numbered according to its appearance in Table I.

| Study No. | ζ Potential

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a +

bψ0,Y

|

a

+ bψ0,A

|

|||||

| r2 | a | b | r2 | a | b | |

| 1 | 0.911 | 3.7a | 0.761 | 0.929 | 0.0a | 0.723 |

| 2 | 0.923 | 0.6a | 0.252 | 0.929 | 0.6a | 0.254 |

| 3 | 0.997 | −1.9a | 0.343 | 0.997 | −1.9a | 0.343 |

| 4 | 0.927 | −4.9a | 0.468 | 0.935 | −5.2a | 0.468 |

| 5 | 0.866 | 0.0a | 0.274 | 0.945 | −5.4 | 0.196 |

| 6 | 0.963 | 15.7 | 0.481 | 0.997 | 4.8 | 0.318 |

Not statistically different from 0.

Within-study correlations for ζ potential versus ψ0,Y are high; r2 ≥ 0.866 in all cases. NaCl and KCl have similar effects on the ζ potential (see solutions 2 and 3 and 11 and 12 in Table I), which justifies the assignment KR,Na = KR,K. CaCl2 and MgCl2 appear to have similar effects on the ζ potentials (see solutions 14 and 15), thereby providing some justification for the assignment KR,Ca = KR,Mg. Furthermore, the fact that points corresponding to Ca2+- and Mg2+-containing solutions all lie essentially on their respective regression lines indicates that KR,Ca and KR,Mg are reasonable relative to other binding constants. The coefficient a is not statistically different from 0 generally, and the regression line in Figure 1a essentially passes through the origin. Most of the values for ψ0,Y are more negative than the corresponding ζ potentials, and b < 1. Part of the explanation is that the potential at the hydrodynamic plane of shear is of lower magnitude than the potential at the membrane surface. The ζ potentials appear to vary from study to study even for similar solutions, perhaps reflecting differences in ςintrinsic. This is reflected in the values for b in Table II. The first study shown in Table I is different from the others because of its high value for b. Points corresponding to that study are denoted by shaded symbols in Figure 1, where it can be seen that those points constitute the principal outliers. A known model deficiency (Yermiyahu et al., 1997c) is revealed in the last two studies shown in Table I. Those studies and others indicate that at low pH the ζ potential becomes positive, but declining pH by itself cannot drive ψ0,Y to positive values (see Table II).

Adjusting the Model to Improve the Correlations between ψ0 and ζ Potentials

The inability of low pH alone to increase ψ0,Y above 0 follows from the fact that the 1:1 binding of monovalent cations to negative sites can only neutralize the PM surface. Consequently, our first step toward the improvement of the model was to assume ion binding to the neutral sites, an assumption with some experimental justification (Akeson et al., 1989). To implement the change, a value of 2.4 μmol m−2 was assigned to [PT] on the basis of the space occupied by phosphatidic acids in biological membranes (Akeson et al., 1989). Next, all binding constants for the neutral site were assigned values proportional to the binding constants for the negative site. Trial values for the proportionality were assigned until the sum of the r2 values for ζ potential versus ψ0 for the six studies reached a maximum at KP,I = KR,I/180.

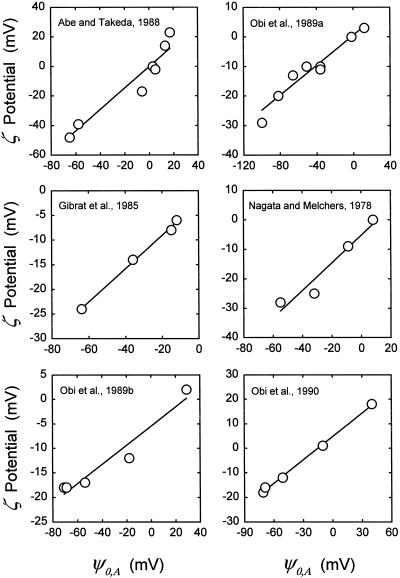

These limited changes (assignments: [PT] = 2.4 μmol m−2 and KP,I = KR,I/180) increased r2 for ζ potential versus ψ0 for all but one study, in which r2 did not change (Table II). Figure 2 presents plots of ζ potential versus ψ0,A for each study (ψ0,A refers to ψ0 computed by the adjusted model). The biggest increases in r2 were in the problematical last two studies. Now the model predicts positive values for ψ0 at low pH; note the left-to-right shift in the low-pH points in Figure 1b. The changes also generally reduced the values of a. The first criterion for the improvement of the model, an increase in the within-study correlations for ζ potential versus ψ0, has been met. The second criterion, the avoidance of a significant degradation of the correspondence between measured and computed ion sorption observed in the study by Yermiyahu et al. (1997c), needs to be considered.

Figure 2.

ζ potentials of plant protoplasts or PM vesicles plotted against ψ0,A for the individual studies presented in Table I. See legend to Figure 1 for details.

Agreement between the Original and the Adjusted Models Relative to Ion Binding

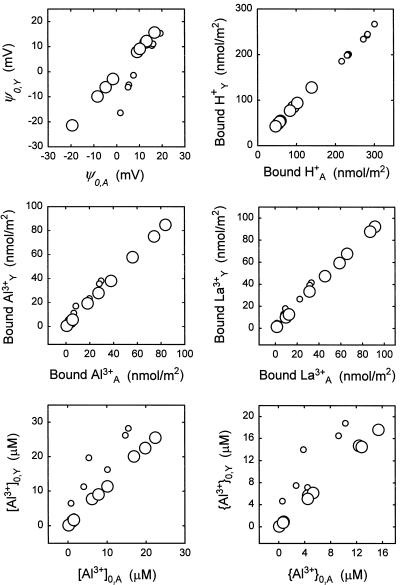

The original model of Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) was based on ion sorption, not ζ potentials, and the original model and the adjusted model disagree significantly in the computed values for ψ0 at low pH (Table I). Does that mean that the models disagree with respect to the computed sorption of ions at low pH? To make the determination, ψ0 and ion binding were computed by the original and the adjusted models for solutions factorial in pH (3.7 and 4.7), [AlCl3] (1, 10, and 100 μm), and [LaCl3] (10, 100, and 1000 μm). Figure 3 illustrates the excellent agreement of the models for ion binding despite disagreement for ψ0,Y and ψ0,A at pH 3.7. (In the case of ions with high binding constants, sorption is virtually equivalent to binding.) Thus, both models predict ion binding accurately, but the adjusted model predicts ψ0 more accurately. Differences in ψ0 between the two models may have little effect on ion binding, but a greater effect on [IΖ]0 and {IΖ}0 is expected and was observed (bottom two panels of Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Surface densities of PM-bound ions, ψ0, [Al3+]0, and {Al3+}0 calculated by the model of Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) (subscript Y) and the adjusted model of the present study (subscript A). Responses were for solutions factorial in pH (3.7, small symbols; 4.7, large symbols), [AlCl3] (1, 10, and 100 μm), and [LaCl3] (10, 100, and 1000 μm).

Accounting for the Differences between ζ Potential and ψ0

Despite good within-study correlations between ζ potential and ψ0, some large differences between these values persist (Table I). The values for b are all less than 1 (Table II), and the sum of squares for the differences between ζ potential and ψ0,A for all 35 values is 37,133. Some of the differences may be attributable to the fact that the ζ potential measures ψs, the electrical potential at the plane of shear, at distance s from the PM surface (McLaughlin, 1989). ψs and ψ0 are related according to the approximation ψs ≈ ψ0exp(−κs), where κ ≈ 3.29I1/2 and I is the ionic strength in the bulk-phase medium (Morel and Herring, 1993). Greater precision for ψs can be achieved using the second program mentioned in the introduction. In our study the sum of squares for ζ potential versus ψs,A decreases as s increases, reaches a minimum of 3176 at s = 3.8 nm, and then increases again. For phospholipid vesicles, the plane of shear is <1 nm from the PM surface (McLaughlin, 1989), but may be much higher for the PM, which incorporates glycolipids, proteins, and other constituents that project from the surface of the lipid bilayer. Figure 1c presents a plot of ζ potential versus ψ2,A; note the increases in slope and fit.

A second possible source of the difference between ζ potential and ψ0,A is that ςintrinsic may genuinely have been more negative for the PM studied by Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) than for the PM of the other studies, assuming a less negative ςintrinsic did reduce the sum of squares, but that adjustment did not improve the model according to the criteria used above. A third source of error is the apparent differences in ςintrinsic among the studies as indicated by differences in b in Table II. Consequently, we recommend only the adjustments [PT] = 2.4 μmol m−2 and KP,I = KR,I/180 and make the assumption that most of the differences between ζ potential and ψ0,A can be accounted for by the fact that the ζ potential is measured at some distance from the PM surface. Whatever the differences between ζ potential and ψ0,A, the within-study proportionality between the two is very precise, and the adjusted model accurately predicts measured ion sorption in wheat.

Further Confirmation of the Binding Constants

In the exercise that follows we attempt to derive values for binding constants solely from the ζ potentials shown in Table I. The optimization criterion of close agreement with the study of Yermiyahu (1997c) with respect to sorption was abandoned. Instead, parameters were varied to minimize (sum of squares)/r2 using all 35 values. The only constraints were KR,Ca = KR,Mg, KR,Na = KR,K, and constant KR,I/KP,I. Thus, these seven parameters were evaluated: [RT], [PT], KR,H, KR,La, KR,Ca, KR,K, and KR,I/KP,I. The procedure was to successively hold six parameters constant and optimize the seventh. Stable values were achieved, irrespective of starting values. Figure 1d presents ζ potential versus ψ0 obtained using the new parameters. Despite a better fit and a unit slope for the combined data, the within-study correlations were poorer, and agreement with Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) was lower than for the previous adjusted model.

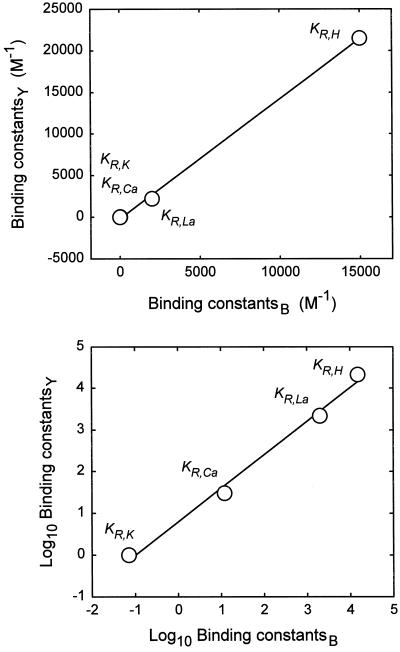

The optimization yielded these values for binding at the negative site: KR,H = 15,000, KR,La = 2,000, KR,Ca = KR,Mg = 12, and KR,Na = KR,K = 0.07. These values may be compared with the former values 21,500, 2,200, 30, and 1, respectively. Figure 4 presents a plot of the two sets of binding constants and their log10 values. The high correlations in Figure 4 provide independent verification of the relative values of the binding constants.

Figure 4.

Binding constants determined on the basis of ion sorption (Yermiyahu et al., 1997c) (subscript Y) plotted against constants determined on the basis of published ζ potentials (subscript B). (See Fig. 1d for details.)

Binding Constants for Al3+ and for Anions

Al3+ does not appear in Table I, so no confirmation of KR,Al (Yermiyahu et al., 1997c) can be obtained from the ζ potentials there, but some additional data indicate the suitability of the binding affinities presented here. Akeson et al. (1989) calculated that the binding of Al3+ to phosphatidylcholine liposomes was 560 times greater than the binding of Ca2+, and Jones and Kochian (1997) estimated that Al3+ binding to wheat microsomes was 300 times greater than Ca2+ binding. Our ratio of binding affinities for Al3+ and Ca2+ is 667. Wilkinson et al. (1993) observed a crossover (ψ0 = 0) from negative to positive potentials in fish gill cells when [AlCl3] = 16 μm in a background of 0.1 m NaCl at pH 4.5. Our model predicts a crossover when [AlCl3] = 21.6 μm under similar conditions. Thus, two studies indicate lower constants and a third study indicates higher constants for Al3+. Those studies, together with some confidence inspired by the verified suitability of the constants for the other ions, indicate that the original value for KR,Al presented by Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) may also be suitable.

In all of our studies we assumed no binding of anions to negative sites, but the assignment of cation binding to neutral sites would seem to warrant a similar binding of anions to neutral sites. In the adjusted model we made the assignments KP,Cl = KP,K and KP,SO4 = KP,Ca, but these assignments had little effect on ψ0.

Induction of Positive ζ Potentials

Experimental evidence indicates that H+, Al3+, and La3+ can induce ζ potentials to shift from negative to positive values (Wilkinson et al., 1993; refs. in Table I), but limited evidence indicates that Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and K+ cannot cause this shift (Gibrat et al., 1985; Obi et al., 1989b; refs. in Table I). Our adjusted model is in practical agreement with the experimental data because H+, Al3+, and La3+ do cause ψ0,A to shift to positive values at appropriate concentrations, but Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and K+ do not cause this shift at physiologically reasonable concentrations. The model predicts crossover at the following concentrations: [Al3+] = 20.1 μm, [La3+] = 183 μm, [H+] = 199 μm, [Ca2+] = 24.7 mm, and [K+] = 4.0 m in a background of 0.5 mm CaCl2 at pH 4.5, unless the latter two were varied.

CONCLUSIONS

Although generally neglected, ψ0 appears to play a significant role in plant-mineral interactions. The neglect may reflect the difficulty of measuring ψ0 and the previous absence of verified model parameters for its computation in biological membranes. In particular, binding constants for the PM have been determined infrequently. The study of Yermiyahu et al. (1997c) provided the first constants for trivalent cations, despite the great importance of the environmental toxicant Al3+. The present study achieves the goal of providing a model, using a single set of model parameters, suitable for the computation of ψ0 (or at least a value that is proportional to ψ0) for PM from diverse plant sources. In addition, the model allows the computation of ion binding, concentrations, and activities (or at least values that are proportional to them) at the PM surface.

Some limitations of the model are apparent, including some questions about the suitability of the Gouy-Chapman theory for biological membranes discussed by Barber (1980) and McLaughlin (1989). Some questions concerning the use of [IΖ]0 versus {IΖ}0 in the derivation of the Gouy-Chapman-Stern model and in the interpretation of physiological responses remain unresolved to our knowledge (Kinraide, 1994). It is recognized that the PM contains more than two ion-binding sites; R− and P0 merely represent composites of many sites. We assume that the PM expresses much spatial variability with respect to charge density. Specialized structures such as the outer orifice of ion channels may have exceptional distributions of charges and binding sites (Hille, 1992). Therefore, our model computes global properties only, yet these properties have been remarkably helpful in the interpretation of plant-mineral interactions. A worthwhile goal for future research will be the extension of the model to other important nutrients and toxicants.

Abbreviations:

- ψm

transmembrane electrical potential difference

- ψ0

electrical potential at the PM surfaceψ0,

- A

ψ0 computed according to the adjusted Gouy-Chapman-Stern model of the present studyψ0,

- Y

ψ0 computed according to a Gouy-Chapman-Stern model presented by Yermiyahu et al. (1997c)

- ς

charge density on the PM surface

- {IZ}0 and {IΖ}∞

activity of ion I with charge Ζ at the PM surface and in the bulk-phase medium, respectively

- [IΖ]0 and [IΖ]∞

concentration of ion I with charge Ζ at the PM surface and in the bulk-phase medium, respectivelyKP,

- I

binding constant for ion I to the PM site P0KR,

- I

binding constant for ion I to the PM site R−

- PM

plasma membrane(s)

- ζ potential

electrical potential of particles at the hydrodynamic plane of shear measured by electrophoresis

LITERATURE CITED

- Abe S, Takeda J. Effects of La3+ on surface charges, dielectrophoresis, and electrofusion of barley protoplasts. Plant Physiol. 1988;87:389–394. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akeson MA, Munns DN, Burau RG. Adsorption of Al3+ to phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;986:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber J. Membrane surface charges and potentials in relation to photosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;594:253–308. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(80)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage RA, Theuvenet ARP, Borst-Pauwels GWFH. Effect of plasmolysis upon monovalent cation uptake, 9-aminoacridine binding and the zeta potential of yeast cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;854:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gage RA, Van Wijngaarden W, Theuvenet ARP, Borst-Pauwels GWFH, Verkleij AJ. Inhibition of Rb+ uptake in yeast by Ca2+ is caused by a reduction in the surface potential and not in the Donnan potential of the cell wall. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;812:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gibrat R, Grouzis J-P, Rigaud J, Galtier N, Grignon C. Electrostatic analysis of effects of ion on the inhibition of corn root plasma membrane Mg2+-ATPase by the bivalent orthovanadate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;979:46–52. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibrat R, Grouzis J-P, Rigaud J, Grignon C. Electrostatic characteristics of corn root plasmalemma: effect on the Mg2+-ATPase activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;816:349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Hille B (1992) Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes, Ed 2, Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA

- Jones DL, Kochian LV. Aluminum interaction with plasma membrane lipids and enzyme metal binding sites and its potential role in Al cytotoxicity. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:51–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB. Use of a Gouy-Chapman-Stern model for membrane-surface electrical potential to interpret some features of mineral rhizotoxicity. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1583–1592. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB. Three mechanisms for the calcium alleviation of mineral toxicities. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:513–520. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB, Ryan PR, Kochian LV. Interactive effects of Al3+, H+, and other cations on root elongation considered in terms of cell-surface electrical potential. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:1461–1468. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A, McLaughlin A, McLaughlin S. The adsorption of divalent cations to phosphatidylglycerol bilayer membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;645:279–292. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, Ed 2. London: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S. The electrostatic properties of membranes. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1989;18:113–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.18.060189.000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel FMM, Hering JG. Principles and Applications of Aquatic Chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Melchers G. Surface charge of protoplasts and their significance in cell-cell interaction. Planta. 1978;142:235–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00388219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nir S, Rytwo G, Yermiyahu U, Margulies L. A model for cation adsorption to clays and membranes. Colloid Polym Sci. 1994;272:619–632. [Google Scholar]

- Nobel P. Physicochemical and Environmental Plant Physiology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Obi I, Ichikawa Y, Kakutani T, Senda M. Electrophoretic studies on plant protoplasts. I. pH dependence of zeta potentials of protoplasts from various sources. Plant Cell Physiol. 1989a;30:439–444. [Google Scholar]

- Obi I, Ichikawa Y, Kakutani T, Senda M. Electrophoresis, zeta potential and surface charges of barley mesophyll protoplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1989b;30:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Obi I, Kakutani T, Imaizumi N, Ichikawa Y, Senda M. Surface charge density of hetero-fused plant protoplasts: an electrophoretic study. Plant Cell Physiol. 1990;31:1031–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Suhayda CG, Giannini JL, Briskin DP, Shannon MC. Electrostatic changes in Lycopersicon esculentum root plasma membrane resulting from salt stress. Plant Physiol. 1990;93:471–478. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatulian SA (1998) Surface electrostatics of biological membranes and ion binding. In TS Sørensen, ed, Surface Chemistry and Electrochemistry of Membranes. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp 871–922

- Theuvenet APR, Borst-Pauwels GWFH. Effect of surface potential on Rb+ uptake in yeast: the effect of pH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;734:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wagatsuma T, Akiba R. Low surface negativity of root protoplasts from aluminum-tolerant plant species. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1989;35:443–452. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KJ, Bertsch PM, Jagoe CH, Campbell GC. Surface complexation of aluminum on isolated fish gill cells. Environ Sci Technol. 1993;27:1132–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Yermiyahu U, Brauer DK, Kinraide TB. Sorption of aluminum to plasma membrane vesicles isolated from roots of Scout 66 and Atlas 66 cultivars of wheat. Plant Physiol. 1997a;115:1119–1125. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.3.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yermiyahu U, Nir S, Ben-Hayyim G, Kafkafi U, Kinraide TB. Root elongation in saline solution related to calcium binding to root cell plasma membranes. Plant Soil. 1997b;191:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Yermiyahu U, Rytwo G, Brauer DK, Kinraide TB. Binding and electrostatic attraction of lanthanum (La3+) and aluminum (Al3+) to wheat root plasma membranes. J Membr Biol. 1997c;159:239–252. doi: 10.1007/s002329900287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]