Abstract

PURPOSE

We conducted a population-based pediatric study to determine the incidence of symptomatic kidney stones over a 25-year period and to identify factors related to variation in stone incidence during this time period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Rochester Epidemiology Project was used to identify all children (ages <18 years) diagnosed with kidney stones in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1984–2008. Medical records were reviewed to validate first time symptomatic stone-formers with identification of age-appropriate symptoms plus stone confirmation by imaging or passage. The incidence of symptomatic stones by age, gender, and time period was compared. Clinical characteristics of incident stone-formers were described.

RESULTS

There were 207 children who received a diagnostic code for kidney stones, 84 (41%) of whom were validated as incident stone-formers. The incidence rate increased 4% per calendar year (p=0.01) throughout the 25-year period. This was due to a 6% per year rise of incidence in children aged 12–17 years (p=0.02 for age x calendar year interaction) with an increase from 13 per 100,000 person-years in 1984–1990 to 36 per 100,000 person-years in 2003–2008. Computed tomography (CT) identified the stone in 6% (1/18) of adolescent stone-formers from 1984–1996 versus 76% (34/45) from 1997–2008. The incidence of spontaneous stone passage in adolescents did not increase significantly between these two time periods (16 versus 18 per 100,000 person-years, p=0.30)

CONCLUSIONS

The incidence of kidney stones increased dramatically among adolescents in the general population over a 25-year period. The exact cause of this finding remains to be determined.

Keywords: Kidney stone, children, epidemiology, computed tomography

Introduction

Stone events have been identified by hospital admissions,1 hospital-based outpatient surgeries, emergency department visits,2 and outpatient nephrology clinic visits3 in several recent studies that have reported an increase in pediatric nephrolithiasis. A population-based study is needed to confirm the rising incidence of pediatric nephrolithiasis. Furthermore, the reasons for the apparent increase in pediatric nephrolithiasis have not been clearly explained. Some have suggested that factors linked to nephrolithiasis in the adult population such as obesity and diabetes might be involved.3,4,5,6 We sought to improve the current understanding of nephrolithiasis in children with a population-based study. Our primary goal was to determine the trend in the incidence of pediatric stone disease over time in a defined geographic region and to identify potential causes of any changes observed.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, potential pediatric stone-formers were identified through the Rochester Epidemiology Project. This database passively captures clinical events by linking medical records and diagnostic codes from every health care provider in Olmsted County for nearly all past and present residents.7 Potential incident stone-formers were identified by International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition codes 592, 594, and 274.11 that had been assigned to any resident under 18 years of age from 1984–2008. Corresponding patient records were then manually reviewed to verify the presence of symptoms and either radiographic confirmation of a urological stone in a location consistent with symptoms or stone visualization on passage. For young children, symptom criteria included gross hematuria, inconsolability, increased irritability, and vomiting not explained by other illness. The charts of all validated stone-formers were abstracted for information related to presentation, management, laboratory evaluation, comorbidities, and medications. Children were excluded if they had a history of nephrolithiasis prior to 1984, were not Olmsted County residents at the time of stone event, or if they had incidental asymptomatic stones only (biased by limited rate of abdominal imaging studies in children).

Age and sex-specific incidence rates (per 100,000 person-years of risk) were calculated for each year by dividing the number of first-time validated stone formers by the estimated Olmsted County population as determined by the US decennial census with linear interpolation for inter-census years. Adjusted rates (age-adjusted rates by sex and an age-sex adjusted rate) were based on the age and sex distribution of the US 2000 total population aged 0–17 years. Age and time period were analyzed as continuous and categorical variables using the groupings 0–5, 6–11, and 12–17 years and 1984–1990, 1991–1996, 1997–2002, and 2003–2008, respectively. Age, gender, and calendar year differences in the incidence of kidney stones were assessed with Poisson regression. A p-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS®, version 9.2.

Results

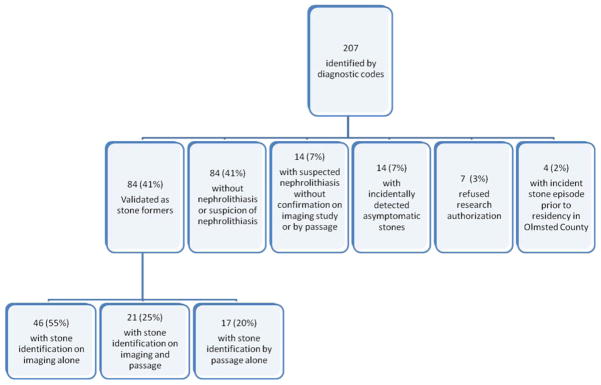

A total of 207 children were identified through diagnostic codes and, of these, 84 (41%) were validated as incident stone-formers (Figure 1). There were 49 female (58%) and 35 male (42%) stone-formers. The age-adjusted incidence rates in females and males over the 25-year period were 12.6 (95% CI: 9.1 to 16.2) and 8.6 (95% CI: 5.7 to 11.4) per 100,000 person-years (p=0.08), respectively, with an overall age-sex-adjusted incidence rate of 10.5 (95% CI: 8.3 to 12.8) per 100,000 person-years. The incidence rate was higher for adolescents (ages 12–17: 23.9 per 100,000 person-years) than younger children (ages 0–5: 4.1 per 100,000 person-years; ages 6–11: 3.7 per 100,000 person-years) (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Study map of the validation of incident symptomatic pediatric stone-formers in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1984–2008

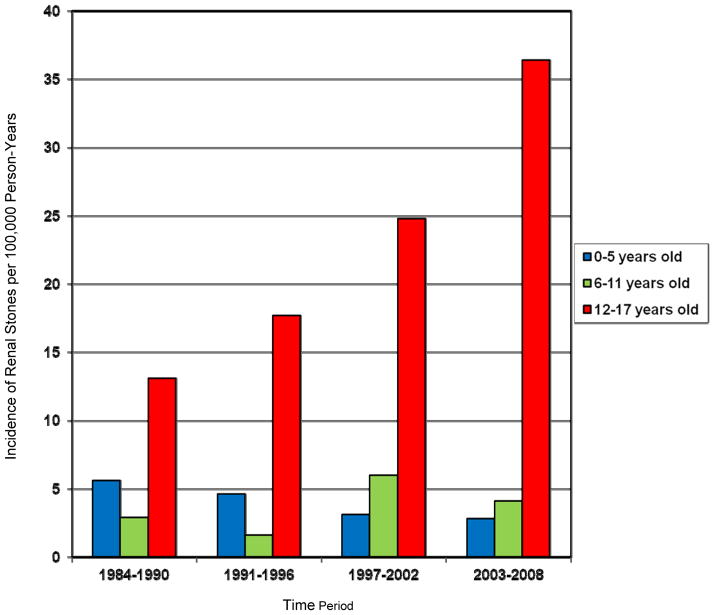

The incidence of stones varied by age and time period (Table 1). The overall incidence of nephrolithiasis increased an average of 4% per year (p=0.01) over the 25-year period. The age-sex adjusted rate rose from 7.2 (95% CI 3.4 to 10.9) per 100,000 person-years in 1984–1990 to 14.5 (95% CI 9.6 to 19.4) per 100,000 person-years in 2003–2008. This temporal increase was attributable to a rising incidence in the 12–17 year-old cohort (p=0.02 for age x time period interaction) (Figure 2). The incidence of stones in adolescents increased 6% per year (p=0.004) over the 25-year period. The increasing incidence over time did not differ by gender (p=0.63) and there were no significant gender differences based on age (p=0.36).

Table 1.

Population-based incidence of symptomatic pediatric nephrolithiasis per 100,000 person-years by time period, gender and age

| 1984–1990 | 1991–1996 | 1997–2002 | 2003–2008 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both sexes | ||||

| Crude rate (N) | 6.9 (14) | 7.5 (14) | 11.5 (23) | 14.9 (33) |

| Age-sex adjusted rate [95% CI] | 7.2 [3.4,10.9] | 7.9 [3.8,12.1] | 11.3 [6.7,15.9] | 14.5 [9.6,19.4] |

| Boys | ||||

| Crude rate (N) | 7.8 (8) | 5.3 (5) | 6.8 (7) | 13.2 (15) |

| Age adjusted rate [95% CI] | 7.9 [2.4,13.4] | 5.6 [0.7,10.5] | 6.7 [1.7,11.7] | 12.9 [6.4,19.4] |

| Girls | ||||

| Crude rate (N) | 6.1 (6) | 9.9 (9) | 16.4 (16) | 16.7 (18) |

| Age adjusted rate [95% CI] | 6.4 [1.3,11.5] | 10.3 [3.6,17.1] | 16.1 [8.2,24.0] | 16.2 [8.7,23.7] |

| Both sexes | ||||

| Age specific rate (Number) | ||||

| 0–5 yrs | 5.6 (4) | 4.6 (3) | 3.1 (2) | 2.8 (2) |

| 6–11 yrs | 2.9 (2) | 1.6 (1) | 6.0 (4) | 4.1 (3) |

| 12–17 yrs | 13.1 (8) | 17.7 (10) | 24.8 (17) | 36.4 (28) |

Figure 2.

Incidence of symptomatic nephrolithiasis in children by age group and time period in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1984–2008

The mean age of presentation for symptomatic pediatric nephrolithiasis was 13.2 years (median 15.2 years); it was 11.4 (median 14.6) in 1984–1996 and 14.1 (median 15.9) in 1997–2008. Clinical characteristics of these stone formers (Online table 1) revealed that the majority of children presented to the Emergency Department (76%), although a substantial number (17%) were diagnosed in an outpatient primary care setting. Medical comorbidities included prior urinary tract infections (23%), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (21%), and developmental/genetic/systemic abnormalities (21%). There was a family history of stone disease documented in 40% of children. Diet histories and recommendations for any changes in diet were not recorded in a standardized fashion to allow for meaningful analysis. Body mass index (BMI) data at presentation was available in 61 of the 84 stone-formers (73%). The mean ± standard deviation BMI was 20.6 ± 5.2 for all children (range 5.7–37.2) and was 18.9 (n=18, males=17.3, females=19.8) from 1984–1996 and 21.4 (n=43, males=19.4, females=22.4) from 1997–2008 (p=0.08). The mean BMI in adolescent females was 20.7 (n=8) and 23.3 (n=22) in 1984–1996 and 1997–2008, respectively (p=0.14), and was 21.8 (n=2) and 21.3 (n=11) in these respective time periods in adolescent males (p=0.89).

A urologist was consulted within 15 days of the diagnosis in 45% of children. Surgery was performed in 24/84 children (Table 2). A metabolic workup was performed in 62% of the cohort and metabolic abnormalities were detected in 33/52 (63%) with hypercalciuria being most common (Table 3). As of 2011, 37/84 (44%) patients have had 120 subsequent stone events; 17(46%) of these patients have required surgical intervention for 39 subsequent stone events.

Table 2.

Surgical interventions in children with incident symptomatic nephrolithiasis in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1984–2008.

| Surgical intervention (84 patients) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Ureteroscopy | 9(11) |

| Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy | 6(7) |

| Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy + ureteroscopy | 2(2) |

| Isolated stent placement | 2(2) |

| Open lithotomy | 2(2) |

| Percutaneous lithotripsy | 2(2) |

| Percutaneous lithotripsy + ureteroscopy | 1(<1) |

Table 3.

Metabolic and stone characteristics of children with incident symptomatic nephrolithiasis in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1984–2008.

| Metabolic abnormality (52 patients) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Hypercalciuria | 15(62) |

| Hyperoxaluria | 6(18) |

| Hypocitraturia | 4(12) |

| Hyperuricosuria | 3(9) |

| Hypercalcemia | 2(6) |

| Hypercalcemia & hypocitraturia | 1(3) |

| Acidosis | 1(3) |

| Hypokalemia | 1(3) |

| Primary stone composition (65 patients) | n (%) |

| Calcium oxalate monohydrate | 26(40) |

| Calcium oxalate dihydrate | 20(31) |

| Calcium phosphate | 16(25) |

| Magnesium ammonium phosphate hexahydrate | 2(3) |

| Uric acid | 1(2) |

The mean stone diameter was 4.2 mm (range 1–20, n=67) on imaging studies. Fifteen children (22%) presented with bilateral stones. Overall, 37 had kidney stones, 32 had ureteral stones, and 11 had both. Only 10% (2/21) of imaged stones were identified by computed tomography (CT) from 1984–1996 versus 82% (41/50) from 1997–2008 (p=<0.001). In children aged 12–17 years, 6% (1/18) stones were identified with CT from 1984–1996 versus 76% (34/45) from 1997–2008 (p=<0.001). Of the 34 stones diagnosed by CT in this latter time period, 21 were also detected via an alternate imaging modality or spontaneous passage. The incidence of spontaneous stone passage among adolescents in 1984–1996 and 1997–2008 was 16.1 and 17.9 per 100,000 person-years, respectively (p=0.30). There were no other significant temporal trends in diagnostic characteristics among adolescents (Online table 2).

Discussion

Our 25-year study of children in Olmsted County demonstrates that the incidence of nephrolithiasis has increased threefold in adolescents, rising 6% per year throughout the study period. The incidence has remained stable in younger age groups. The overall incidence of nephrolithiasis among children was roughly tenfold less than adults in Olmsted County, where the most recent data from 2000 revealed rates decreasing by 1.7% per year among men and increasing by 1.9% per year among women.8 Because of the rising incidence among adolescents the overall incidence of nephrolithiasis in the pediatric population appears to be increasing at a rate of 4% per year. Thus, our population-based study confirms previous referral- and institution-based studies that reported a rise in the incidence of pediatric nephrolithiasis.1,2,3

Treatment of nephrolithiasis has been reported to be on the rise at select freestanding pediatric hospitals based upon analyses of inpatient admissions, emergency department visits, and outpatient surgeries.2 The number of children diagnosed with nephrolithiasis at these hospitals in a national database, rose from 125 in 1999 to 1,389 in 2008, a notable increase in comparison to new diagnoses of appendicitis and bronchiolitis over the same time period.2 Similarly, a single institution study demonstrated a 4.6-fold increase in cases of pediatric nephrolithiasis per every 100 new children observed between 1994–1996 and 2003–2005.3 Referral patterns and coding errors were potential sources of bias in these reports. However our population-based study design enabled us to capture all stone-related health care provided in a geographically-defined population, and a detailed manual chart review validated and characterized all cases. Of note, outpatient visits to primary providers accounted for nearly 20% of pediatric stone events in our study, making this an important cohort to capture given that pediatric nephrolithiasis does not typically require hospital admission for treatment or evaluation.9 Overall, our data confirmed the increase in incidence of stones in children and determined that it was isolated to the adolescent population.

Our study identified the 12–17 year-old age group as the predominant group of pediatric stone-formers in Olmsted County with a median age of presentation of 15.2 years across the 25-year study period. Although this contrasts with epidemiologic studies from abroad where the median ages of presentation are less than 10 years,10,11 this is in keeping with United States hospital-based studies that have shown a notably higher number of stone-formers aged 12–20 years2,12 with a mean patient age of 11.9.2 In these reports, stone formation was greater in females than males after the ages of 10–12 years, while the reverse was true for in the younger patient cohorts. Although numerous other studies have demonstrated a strong male predominance in pediatric urolithiasis,13 we did not observe any statistically significant gender difference in the incidence of nephrolithiasis.

The metabolic and stone characteristics we observed were similar to prior pediatric nephrolithiasis cohorts. For example, we noted calcium oxalate as the primary component in 71% of analyzed stones.13 Hypercalciuria (62%) was the most common disorder observed among those children who underwent metabolic evaluation in our population-based study. Up to 84% of stone forming children have been previously reported to have an identifiable metabolic abnormality, although this number could be inflated by referral bias,14 Hypercalciuria has been noted in up to 50%, hyperoxaluria in 20%, hyperuricosuria in 8%, and cystinuria in 7% of pediatric stone-formers.1,15,16 The extent of metabolic workup performed in our cohort varied between providers and, despite the recommendation that all children undergo metabolic evaluation after their first stone episode,17 40% of the children in our study did not undergo metabolic testing at all. Furthermore, while it is recommended that pediatric stone-formers be counseled on increased water intake and decreased dietary sodium, meat, and oxalate intake,1 there was no consistent documentation of these principal recommendations. Such findings highlight the need for improved education of community practitioners.

The reason for the rise in adolescent nephrolithiasis is not clear. It has been suggested that increasing sensitivity of radiologic imaging and use of CT may account for a perceived increase in the incidence of pediatric nephrolithiasis.1,2,3,18 Our results support this hypothesis since there was no increase in spontaneous stone passage observed over time in the adolescent population despite a substantial increase in CT-identified stones over the same period of time. Instead of a true increase in the incidence of symptomatic stones, CT scans may have helped identify symptomatic stone events in adolescents that would have been missed in the era before widespread CT scanning for suspected stones. Consistent with this hypothesis, the mean stone diameter by CT scan was 3.7 mm compared to 5.2 mm for symptomatic stone episodes diagnosed with other imaging modalities (p=0.07). CT is undeniably the most sensitive imaging modality for stone detection as pediatric studies have shown that kidney-ureter-bladder x-ray detects about 50% of stones visualized on CT,19 ultrasound detects about 60% (90% of renal and 25–38% of ureteral stones),9,19 and excretory urogram detects about 87%.20 Because non-contrast helical-CT was reported to have 97% sensitivity and 96% specificity for ureteral stones in 1996,21 non-contrast CT was widely advocated in the late 1990s and early 2000s as the imaging modality of choice for suspected nephrolithiasis in the pediatric population.9,22 Correspondingly, the use of CT scanning for diagnosis of pediatric urolithiasis rose from 26% in 1999 to 45% in 2008 with a concomitant decrease in the use of kidney-ureter-bladder x-ray plus intravenous pyelogram from 59% to 38% over this time.23

Although it has been hypothesized that the rising incidence of stone disease in pediatric populations is related to childhood obesity, significant trends in obesity were not observed in the adolescent stone-formers in our study. While recent estimates do report that 31.9% of children are over the 85th percentile for age-adjusted BMI,24 an increased BMI has not been shown to correlate with earlier stone development, large stones, or the need for multiple procedures in a stone-forming population.6 Additionally, evaluation of pediatric stone-formers from 1999 to 2006 did not reveal a significant trend in the prevalence of high BMI.24 Our study demonstrated a stable mean BMI of about 21 in our adolescent population over time. This BMI is similar to that of the general population where the median BMI is 17.75 in boys aged 12 years, 17.1 in girls aged 12 years, 21.9 in boys aged 18 years, and 20.75 in girls aged 18 years.25

There are potential limitations to this study. Unfortunately, retrospective studies such as ours are restricted by the completeness and level of detail present in the medical record. While we could accurately identify children who had symptomatic stone episodes and presented to medical care, the ability to fully characterize stone episodes varied. Documentation of presenting symptoms and signs followed no pattern, particularly as related to negative findings, and supplemental information, such as family history and dietary habits, was inconsistently recorded. Numerous medical personnel treated known and suspect stone-formers. Without a standardized algorithm for evaluation, providers more comfortable using sensitive imaging studies may have captured more incident stone-formers than those who preferred to minimize radiation exposure. This limitation is, in part, an expected trade-off in a population-based study that captures all stone-formers in the community as compared to a referral-based study where more consistent and thorough evaluations are observed. Furthermore, the trends seen in the incidence of pediatric stone disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota may not apply to all populations given that geographic, economic, and ethnic factors are known to predict the incidence of stones in pediatric populations.13 Indeed, the incidence of stone disease in children worldwide varies among regions, ranging from 0.5% to 5%26 with a reported prevalence in the United States ranging from 1:1,000 to 1:7,600.27

Conclusions

Our population-based study found a rise in the incidence of pediatric nephrolithiasis over the past 25 years that is entirely due to an increase in nephrolithiasis among adolescent children. Specifically, there was a three-fold increase in nephrolithiasis from 1984–1990 to 2003–2008 among children in Olmsted County aged 12–17 years while the incidence has remained stable in younger age groups. The exact reason for this is not entirely clear, and this finding may differ in other geographical regions. Metabolic evaluation was not consistently obtained in this population, and thus there is a need for education of providers and referral to specialists with appropriate expertise. Notably, there was no increase in the incidence of spontaneous stone passage among adolescents despite a marked increase in kidney stone diagnosis via CT imaging. Therefore, the increase in the incidence of stones in adolescents may be due to more sensitive imaging technology and temporal trends in CT usage rather than an actual rise in stone disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This project was supported by research grants (DK 83007, DK 78229, and AG 034676) from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Public Health Service.

Key of definitions for abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CT

computed tomography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Moira E. Dwyer, Department of Urology, Rochester, MN

Amy E. Krambeck, Department of Urology, Rochester, MN

Eric J. Bergstralh, Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics, Rochester, MN

Dawn S. Milliner, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Rochester, MN

John C. Lieske, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Rochester, MN

Andrew D. Rule, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Rochester, MN

References

- 1.Tanaka ST, Pope JC., IV Pediatric stone disease. Curr Urol Rep. 2009;10:138. doi: 10.1007/s11934-009-0025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Routh JC, Graham DA, Nelson CP. Epidemiological trends in urolithiasis at United States freestanding pediatric hospitals. J Urol. 2010;184:1100. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VanDervoort K, Wiesen J, Frank R, et al. Urolithiasis in pediatric patients: a single center study of incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. J Urol. 2007;177:2300. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor EN, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Obesity, weight gain, and the risk of kidney stones. JAMA. 2005;293:455. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiSandro M. Pediatric urolithiasis: children as little adults. J Urol. 2010;184:1833. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieran K, Giel DW, Morris BJ, et al. Pedatric urolithiasis: does body mass index influence stone presentation and treatment? J Urol. 2010;184:1810. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melton LJ., III History of the Rochester epidemiology project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieske JC, Pena de la Vega LS, Slezak JM, et al. Renal stone epidemiology in Rochester, Minnesota: an update. Kidney Int. 2006;69:760. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer JS, Donaher ER, O’Riordan MA, et al. Diagnosis of pediatric urolithiasis: role of ultrasound and computed tomography. J Urol. 2005;174:1413. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000173133.79174.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coward RJM, Peters CJ, Duffy PG, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric renal stone disease in the UK. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:962. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.11.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edvardsson V, Elidottir H, Indridason OS, et al. High incidence of kidney stones in Icelandic children. Pediatr Nephol. 2005;20:940. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novak TE, Lackshmanan Y, Trock BJ, et al. Sex prevalence of pediatric kidney stone disease in the United States: an epidemiologic investigation. Urol. 2009;74:104. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faerber GJ. Pediatric urolithiasis. Curr Op Urol. 2001;11:385. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas BJ. Management of stones in childhood. Curr Op Urol. 2010;20:159. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283353b80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naseri M, Varasteh AR, Alamdaran SA. Metabolic factors associated with urinary calculi in children. IJKD. 2010;4:32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spivacow FR, Negri AL, del Valle EE, et al. Metabolic risk factors in children with kidney stone disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1129. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0769-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tekin A, Tekgul S, Atsu N, et al. A study of the etiology of idopathic calcium urolithiasis in children: hypocitraturia is the most important risk factor. J Urol. 2000;164:162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frush DP. Pediatric dose reduction in computed tomography. Health Phys. 2008;95:518. doi: 10.1097/01.HP.0000326335.34281.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oner S, Oto A, Tekgul S, et al. Comparison of spiral CT and the US in the evaluation of pediatric urolithiasis. JBR-BTR. 2004;87:219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Springhart WP, Preminger PM. Advanced imaging in stone management. Curr Op Urol. 2004;14:95. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200403000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith RC, Verga M, McCarthy S, et al. Diagnosis of acute flank pain: value of unenhanced helical CT. AJR. 1996;166:97. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.1.8571915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lumerman J, Meyer DG, Hines J, et al. Unenhanced helical computed tomography for the evaluation of suspected renal colic in the adolescent population: a pilot study. Urol. 2001;57:342. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00872-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Routh JC, Graham DA, Nelson CP. Trends in imaging and surgical management of pediatric urolithiasis at American pediatric hospitals. J Urol. 184:1816. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA. 2008;299:2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Center for Health Statistics. CDC Growth Charts: United States. Body mass index-for-age percentiles. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karabacak OR, Ipek B, Ozturk U, et al. Metabolic differences between the pediatric and adult patients with stone disease. Urol. 2010;76:238. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroovand RL. Pediatric urolithiasis. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:173. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.