Abstract

A challenge in neuroscience is to understand the mechanisms underlying synapse formation. Most excitatory synapses in the brain are built on spines, which are actin-rich protrusions from dendrites. Spines are a major substrate of brain plasticity, and spine pathologies are observed in various mental illnesses. Here we investigate the role of neurobeachin (Nbea), a multidomain protein previously linked to cases of autism, in synaptogenesis. We show that deletion of Nbea leads to reduced numbers of spinous synapses in cultured neurons from complete knockouts and in cortical tissue from heterozygous mice, accompanied by altered miniature postsynaptic currents. In addition, excitatory synapses terminate mostly at dendritic shafts instead of spine heads in Nbea mutants, and actin becomes less enriched synaptically. As actin and synaptopodin, a spine-associated protein with actin-bundling activity, accumulate ectopically near the Golgi apparatus of mutant neurons, a role emerges for Nbea in trafficking important cargo to pre- and postsynaptic compartments.

Most excitatory synapses in the brain are found on dendritic

spines, but the mechanisms underlying synapse formation are poorly understood. Niesmann

et al. investigate the role of neurobeachin in synaptogenesis, and find that

its deletion leads to fewer spinous synapses and altered postsynaptic

currents.

Most excitatory synapses in the brain are found on dendritic

spines, but the mechanisms underlying synapse formation are poorly understood. Niesmann

et al. investigate the role of neurobeachin in synaptogenesis, and find that

its deletion leads to fewer spinous synapses and altered postsynaptic

currents.

Dendritic spines are small, actin-rich protrusions of the dendritic membrane that serve as primary recipients of excitatory synaptic input in the mammalian central nervous system1,2. Spines constitute a specialized compartment that contains the postsynaptic signalling machinery, and organelles such as endosomes or, if present, the spine apparatus3. Many studies indicate that a mutual relationship exists between spine morphology and function of synapses1,4, and that the actin cytoskeleton has a critical role in modulating the efficacy of their pre- and postsynaptic terminals2,5. Dendritic spines can be stable, but they are also dynamic structures that undergo morphological remodelling during development and in adaptation to sensory stimuli or in learning and memory4,6. As numerous psychiatric and neurological diseases are accompanied by alterations of spine numbers or size6,7,8, the elucidation of mechanisms that regulate formation and plasticity of spinous synapses is important.

As neurons are polarized cells and their synapses constitute asymmetric structures, it has been proposed that trafficking of specialized cargo to presynaptic terminals and postsynaptic spines contributes significantly to the development of mature contacts3.

Neurobeachin (Nbea) is a molecule that might be involved in the subcellular trafficking of membrane proteins in neurons (for review ref. 9). Mammalian Nbea is a cytosolic multidomain protein that was discovered as a component of synapses, and found associated with postsynaptic plasma membranes and polymorphic vesiculo-tubulo-cisternal endomembranes10. Moreover, Nbea concentrates near the trans-Golgi network, and its membrane association is stimulated by GTP and antagonized by brefeldin, suggesting a functional link to the post-Golgi sorting or targeting of proteins10. Such a role in targeting has been supported by studies of invertebrate orthologues of Nbea and its ubiquitous isoform Lrba11. SEL-2, the Nbea homologue in Caenorhabditis elegans is responsible for the targeting of LIN-12/Notch and LET-23/EGFR in vulval precursor cells by regulating endosomal traffic and receptor activity12. Affecting a similar pathway in Drosophila, deletion of the fly ortholog rugose caused eye defects based on defective Notch and EGFR signalling13,14. Structurally, Nbea and its orthologues belong to the family of BEACH domain-containing proteins15. In addition, Nbea binds to the regulatory subunit of PKA, therefore allowing classification as an A kinase-anchoring protein10.

Nbea is important from a clinical point of view because it spans a common fragile site on human chromosome 13q13, FRA13 (refs 16, 17), and heterozygous disruptions of the Nbea gene have been linked to idiopathic cases of non-familial autism18,19,20,21. Exploring the idea of autism as a 'synaptopathy'22,23, we previously characterized mouse models of candidate genes for autistic symptoms such as MeCP2, neurexins or neuroligins that show impairments of synaptic function24,25,26,27. This and other work indicates that imbalances between excitatory and inhibitory synaptic activity might form a prominent aspect of the pathomechanism22. Consistently, analyses of deletions of Nbea in mice demonstrated a prominent synaptic phenotype28,29. Knockouts suffer from lethal paralysis in newborns, which is due to an abolished evoked release of presynaptic vesicles at neuromuscular junctions whereas endplate morphology appears intact29. Investigation of the respiratory network in the foetal brainstem demonstrated the importance of Nbea for brain synapses because both action potential-dependent and -independent release are decreased28. Although these earlier investigations revealed an essential role for Nbea at peripheral and central synapses, they could not address important mechanistic questions. Most notably, how does Nbea regulate synaptic function and formation, and how does the far-upstream location of Nbea in the secretory pathway relate to the pleiotropy of synaptic phenotypes?

Here, we investigate a hitherto unknown role for Nbea in spine formation by analysing cultured hippocampal neurons from homozygous knockout mice and cortical brain tissue from adult animals that lack only one Nbea allele. We demonstrate a reduced number of spinous synapses in homozygous and heterozygous neurons, leading to structurally and functionally altered contacts. Moreover, the lack of enriched filamentous actin at mutant synapses, together with the overlapping accumulation of actin and the actin-associated spine protein synaptopodin near the trans-Golgi network reveals novel aspects how Nbea may affect trafficking of pre- and postsynaptic components.

Results

Reduction of axo-spinous synapses in Nbea-deficient neurons

Homozygous Nbea knockout mice die after birth due to impairment of synaptic release from neuromuscular junctions and synapses in the respiratory network28,29. To overcome the limitations in the analysis imposed by premature death, we first investigated the role of Nbea in cultured neurons.

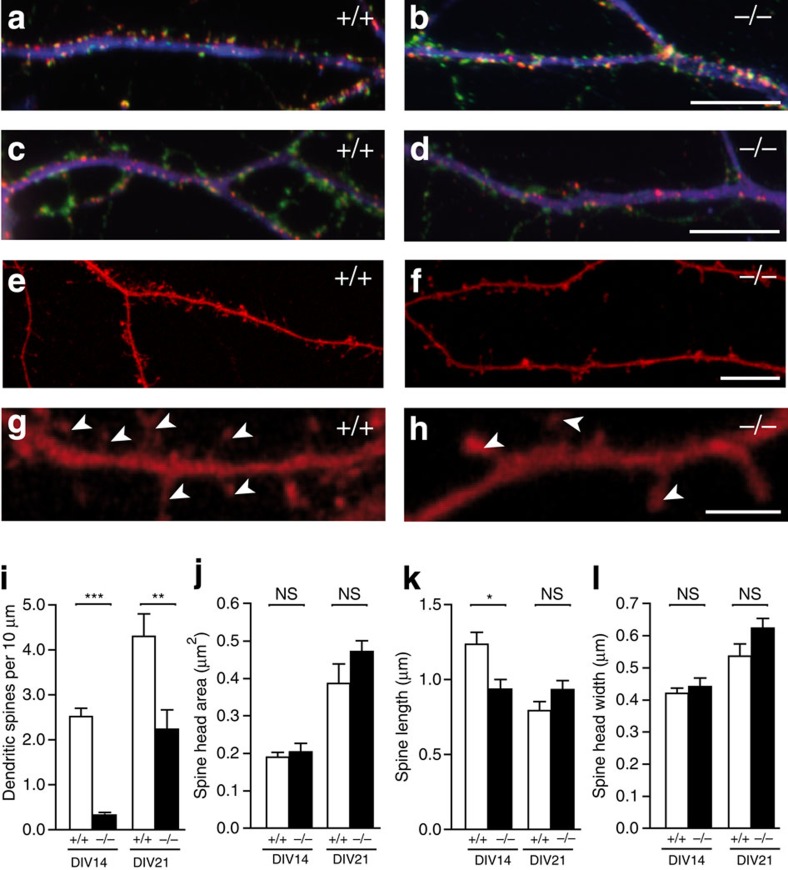

To monitor synaptogenesis in vitro, primary neurons were cultured at low density for 14 and 21 days (DIV14 and DIV21). Cultures from individual hippocampi of homozygous knockouts and littermate controls (Supplementary Fig. S1) were labelled with antibodies against presynaptic synapsin, and postsynaptic PSD-95 or gephyrin to distinguish between putative excitatory and inhibitory synapses (Fig. 1a–d). Presynaptic development was similar in both genotypes as assayed by quantification of synapsin-positive punctae (at DIV21, Nbea+/+: 23.40±1.97 punctae per 10 μm dendrite length, n=7 cultures; Nbea−/−: 19.48±1.37, n=9 cultures; P=0.1140), demonstrating that complete deletion of Nbea did not interfere with the establishment of synapses in general, consistent with earlier studies28,29. However, in knockouts, we observed that excitatory contacts predominantly formed at dendritic shafts (Fig. 1b) instead of a more juxta-dendritic position typical for contacts on spines (Fig. 1a). As the location of gephyrin-positive inhibitory contacts appeared unchanged (Fig. 1c,d), these data suggest that there was a specific reduction of spinous synapses. To directly investigate this possibility, we transfected neurons with monomeric red fluorescent protein (soluble mRFP), which fills all processes including spines (Fig. 1e–h). We observed fewer spines on mutant cells compared with controls (Fig. 1i). Knockout dendrites carried a 48% lower number of mature spine-like protrusions on DIV21 (Nbea+/+: 4.31±0.50, n=6 cultures; Nbea−/−: 2.24±0.43, n=6 cultures; P=0.0047), and the diameter of secondary dendrites was slightly reduced (Nbea+/+: 0.86±0.05 μm, n=4 cultures; Nbea−/−: 0.56±0.03 μm, n=4 cultures; P=0.0015). The difference in spine density was even more pronounced in younger cultures (DIV14; Nbea+/+: 2.52±0.19, n=6 cultures; Nbea−/−: 0.33±0.06, n=6 cultures; P<0.0001) when spines are formed30, suggesting that Nbea is required for the normal formation of spinous synapses in culture.

Figure 1. Nbea knockout neurons in culture fail to develop a normal number of dendritic spines.

(a,b) Immunocytochemistry of dendrites from wild-type (+/+) and Nbea-deficient (−/−) neurons co-labelled with antibodies against synapsin (green), PSD-95 (red) and MAP2 (blue) to visualize pre- and postsynaptic elements of excitatory synapses at DIV21. (c,d) Same experiment as in a,b but using antibodies against gephyrin (red) instead of PSD-95 to reveal inhibitory contacts. (e–h) Representative images of spine-bearing dendrites from wild-type and KO hippocampal neurons transfected with mRFP for 17 days, shown at lower magnification in a low-density culture56 (e,f), and at higher magnification in confocal images (g,h; arrowheads point to the spinous protrusions). (i–l) Histograms showing quantitative comparisons of spine density (i, numbers per dendrite length; data are from 7–9 independent cultures per genotype), and spine dimensions (j, spine head area; k, spine length; l, spine head width; data are from 4–6 independent cultures per genotype) between wild-type and Nbea-deficient neurons at two different time points (DIV14 and DIV21) in vitro. All data are means±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.001, ***P<0.0001, NS, not significant. Scale bars, 10 μm in a–f, 5 μm in g, h. DIV, days-in-vitro.

While fewer spines developed in KOs, those that could be detected (arrowheads in Fig. 1h) were phenotypically normal. Their dimensions were unchanged and within the range of expected values31 (Fig. 1j–l; spine head area: Nbea+/+ 0.39±0.05 μm2, Nbea−/− 0.47±0.03 μm2, P=0.1636; spine length: Nbea+/+ 0.79±0.06 μm, Nbea−/− 0.93±0.06 μm, P=0.1150; and spine head width: Nbea+/+ 0.54±0.04 μm, Nbea−/− 0.62±0.03 μm, P=0.0874; all data are calculated from 15–30 dendrites in four cultures per genotype). Only in younger cultures (DIV14), spine length was slightly reduced in KOs (Nbea+/+ 1.24±0.08 μm, Nbea−/− 0.94±0.06 μm, P=0.0324).

Although studies in cultures combine the advantage of analysing mature neurons from lethal knockouts with superior visibility32, artefacts are always a concern. To brace against this problem, we next studied the density and ultrastructure of synapses in neocortical tissue from adult heterozygous Nbea mice compared with wild-type littermates. These experiments are meaningful because deletion of one Nbea allele produced a 30% reduction of protein (Supplementary Fig. S2), consistent with a diminished immunoreactivity and reduced numbers of Nbea-positive neurons (Supplementary Fig. S2).

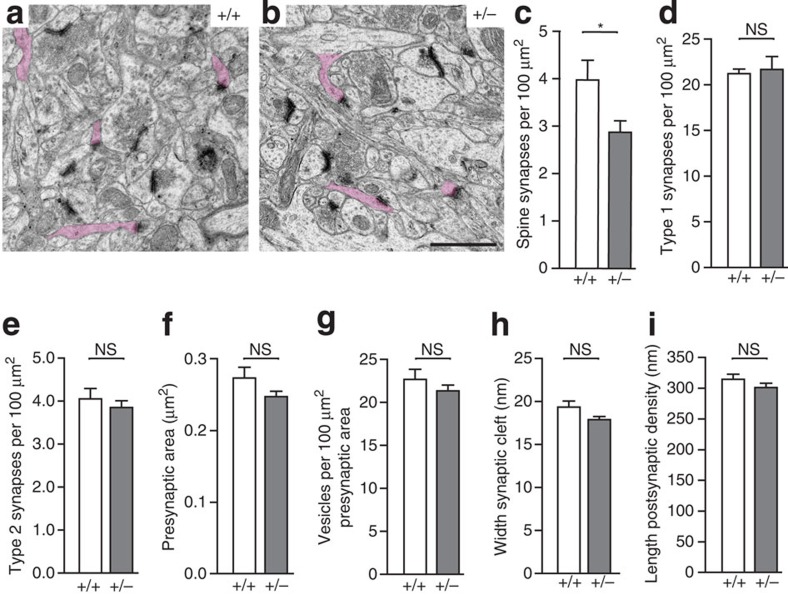

We performed electron microscopy in the neocortex (Fig. 2a,b), and found a significant 28% reduction in the area density of axo-spinous synapses compared with controls (Fig. 2c; Nbea+/+: 3.98±0.42 per 100 μm−2, n=6 cortical series; Nbea+/−: 2.88±0.24 per 100 μm−2, n=6 cortical series; P=0.0436). This effect seemed specific because the overall densities of asymmetric contacts (type 1; Nbea+/+: 21.23±0.51 per 100 μm−2, Nbea+/−: 21.67±1.43 per 100 μm−2; P=0.7768) and symmetric synapses (type 2; Nbea+/+: 4.05±0.24 per 100 μm−2, Nbea+/−: 3.85±0.15 per 100 μm−2; P=0.5034) remained unchanged (Fig. 2d,e). The analysis of additional parameters such as presynaptic terminal area, synaptic vesicle density, length of postsynaptic density or width of synaptic cleft revealed no significant differences (Fig. 2f–i). These results from adult heterozygous mice are in agreement with our culture data (Fig. 1), validating that Nbea is not required for synapse establishment in general but is involved in the formation of spinous synapses.

Figure 2. Selective reduction of axo-spinous synapses in brains of heterozygous Nbea-mutant mice.

(a,b) Representative electron micrographs from layer 5 somatosensory neocortex of adult wild-type (+/+) and heterozygous Nbea (+/−) littermate mice (sample spines are highlighted, magenta). (c–e) Quantitative analysis of three populations of synapses in brain tissue: area density of spinous synapses (c), total number of asymmetric (type 1, presumably excitatory) synapses (d), and symmetric (type 2, presumably inhibitory) contacts (e), each averaged for all cortical layers from six independent cortical series derived from wild-type and heterozygous littermate mice, respectively. (f–i) Histograms showing quantifications of parameters of individual synapses: presynaptic terminal area (f), synaptic vesicle density (g), synaptic cleft width (h) and length of the postsynaptic density (i), measured on 90–100 randomly chosen asymmetric synapses from all cortical layers. All data are means±s.e.m. *P<0.05, NS, not significant. Scale bar, 1 μm in a, b.

Organization of synaptic contacts in absence of Nbea

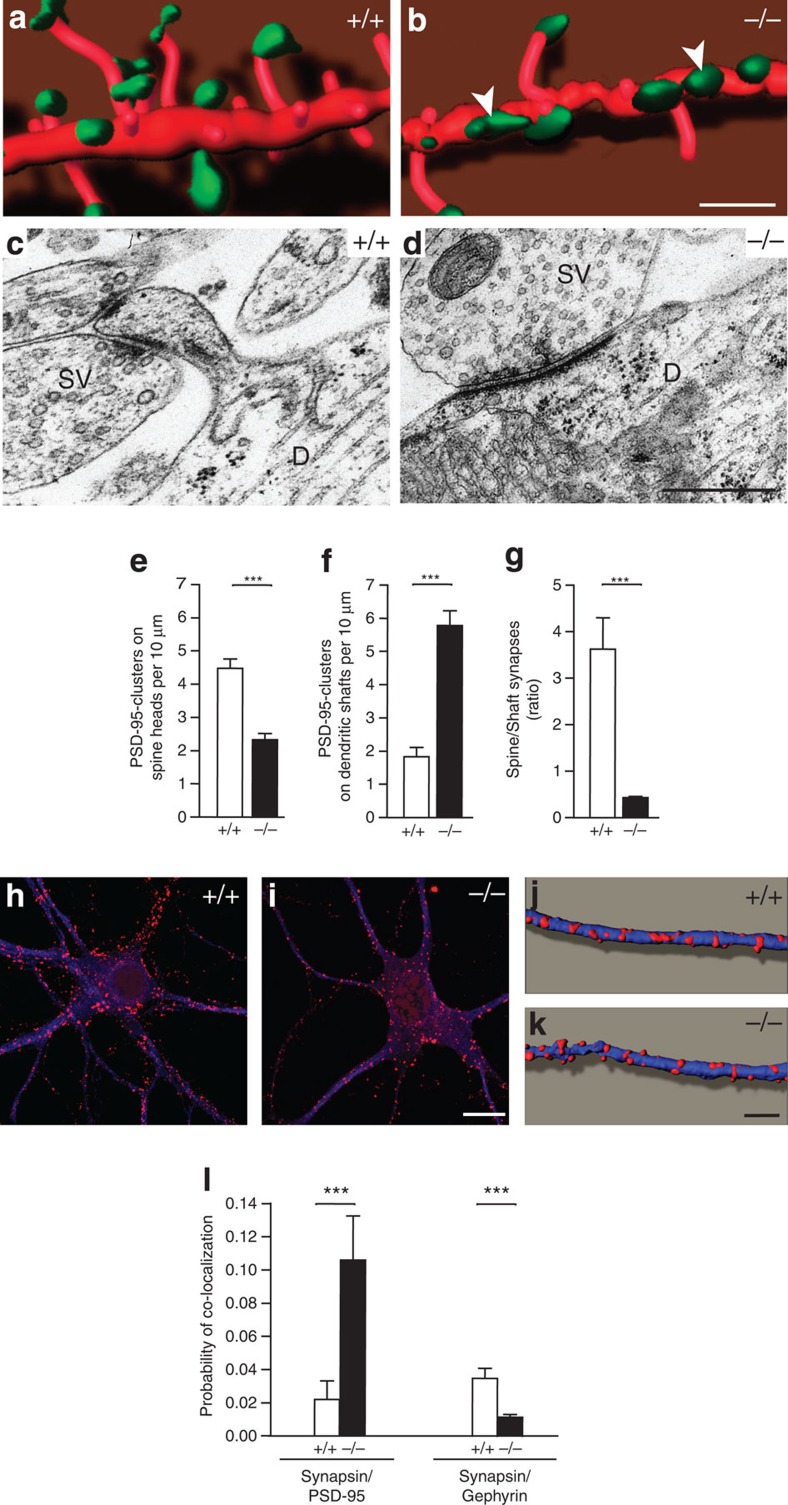

Although the number of synapsin-positive punctae was normal, the location of PSD-95-positive clusters was different in cultured KO neurons (Fig. 1a,b). To investigate the distribution of PSD-95 clusters, stacks of confocal image series (n=10–12 per genotype) were reconstructed (Fig. 3a,b), demonstrating that PSD-95 mostly concentrated on spine heads in controls, but often clustered at dendritic shafts in KOs (arrowheads in Fig. 3b). Electron microscopy of cultures confirmed a comparable ultrastructure of spinous synapses in the KO, if present, but more frequently revealed asymmetric synapses at the shaft (Fig. 3c,d).

Figure 3. Organization of the postsynaptic compartment in absence of Nbea.

(a,b) Spine-bearing dendrites from mRFP-transfected wild-type (+/+) and knockout (−/−) neurons in vitro (red) were co-stained against PSD-95 (green), and stacks of confocal images were three-dimensionally reconstructed using Imaris software. Arrowheads point to PSD-95 clusters that form directly at dendritic shafts of mutant neurons. (c,d) Sample electron micrographs of axo-spinous (c) and axo-dendritic synapses (d) as observed in control and mutant hippocampal neurons. SV, synaptic vesicles; D, dendrite. (e–g) Quantitative analysis of PSD-95 clusters, averaged from 25–29 dendrites from 3–4 independent cultures per genotype, localized on spine heads (e) versus those on dendritic shafts (f), and their ratio in neuronal cultures of both genotypes at DIV21 (g). (h,i) Distribution of the inhibitory postsynaptic scaffolding molecule gephyrin (red) on somata and dendrites of neurons from both genotypes (co-labelling against MAP2, blue). (j,k) Three-dimensional reconstructions from stacks of confocal images as those shown in panel h,i. (l) Degree of co-localization between synapsin-positive punctae with PSD-95 clusters was increased in KO neurons as seen by an increased probability of co-localization (synapsin/PSD-95). In contrast, the probability of co-localization of synapsin with gephyrin was reduced (synapsin/gephyrin), as quantitated on 44–47 dendrites from four independent cultures per genotype. All data are means±s.e.m. ***P<0.001. Scale bars, 5 μm in a, b, 500 nm in c, d, 10 μm in h–i and 5 μm in j–k.

Quantitative comparison revealed that the number of PSD-95 clusters on spine heads was lower in mutants (Nbea+/+: 4.48±0.28, n=25 dendrites per 3 cultures; Nbea−/−: 2.33±0.19, n=29 dendrites per 3 cultures; P<0.0001), whereas their presence on dendritic shafts was increased (Nbea+/+: 1.83±0.27, n=25 dendrites per 3 cultures; Nbea−/−: 5.79±0.45, n=29 dendrites per 3 cultures; P<0.0001) (Fig. 3e,f). Consequently, the ratio of spine/shaft synapses was >1 in controls, but reduced to <1 in KOs (Fig. 3g). In contrast, stainings against gephyrin, a postsynaptic molecule of inhibitory synapses (Fig. 3h,i), and their reconstructions (Fig. 3j,k) were undistinguishable in both genotypes, and the number of gephyrin-positive punctae on the shaft did not differ significantly (Nbea+/+: 4.81±1.13, n=4 cultures per 47 dendrites; Nbea−/−: 3.11±1.06, n=4 cultures per 44 dendrites; P=0.1289).

As the number of PSD-95-positive shaft synapses was increased we also determined a 28% augmented total number of PSD-95-positive clusters in mutants (Nbea+/+: 6.31±0.44, n=25 dendrites per 3 cultures; Nbea−/−: 8.12±0.57, n=29 dendrites per 5 cultures; P=0.0180). To explore the possibility that the increased number of PSD-95-clusters also indicated a shift in the ratio of excitatory to inhibitory contacts, we determined the probability of co-localization between synapsin-positive punctae and PSD-95-positive clusters, and found that it markedly raised in knockouts (Fig. 3l), while the probability of co-localization with gephyrin was reduced (Fig. 3l). These data possibly suggest that knockout neurons tried to compensate the loss of spine synapses by establishing more excitatory synapses at the shaft and by lowering inhibitory inputs. Such a compensation is consistent with the functional importance of spines4, but also mandated analysis of neurotransmission in these cultures.

Nbea deletion reduces spontaneous minirelease

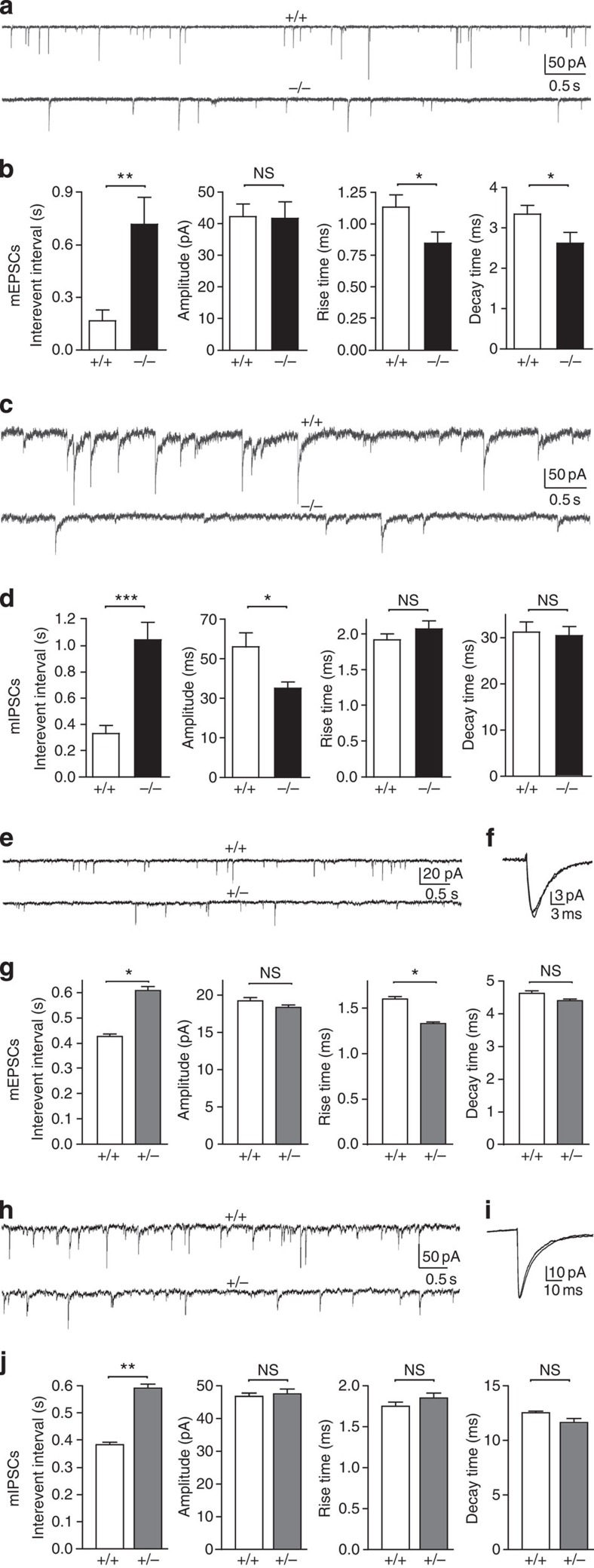

At synapses, different forms of neurotransmitter release are observed, for example, evoked release and spontaneous 'minirelease' that may be mechanistically distinct33. As previous studies demonstrated a role of Nbea in evoked release but reported conflicting results on minirelease28,29, we probed its effect on miniature excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mEPSC and mIPSC).

First, we recorded mEPSCs from cultured neurons in presence of TTX and bicuculline (Fig. 4a,b). Consistent with observations in foetal brainstem neurons28, we found that interevent intervals were four times longer in mutants (Nbea+/+: 165±62 ms, n=15 cells per 3 cultures; Nbea−/−: 718±154 ms, n=16 cells per 3 cultures; P=0.0029) (Fig. 4b), indicating reduced presynaptic release. Mini amplitudes were unchanged (Fig. 4b), in agreement with normal transmitter quanta and similar postsynaptic signalling. We also observed a faster rise time (Nbea+/+: 1.13±0.10 ms, n=15 cells per 3 cultures; Nbea−/−: 0.85±0.09 ms, n=16 dendrites per 3 cultures; P=0.0375) and faster decay time (Nbea+/+: 3.34±0.22 ms, n=15 cells per 3 cultures; Nbea−/−: 2.62±0.27 ms, n=16 dendrites per 3 cultures; P=0.0462) of mEPSCs (Fig. 4b), possibly caused by postsynaptic modifications of spines34 such as reported above.

Figure 4. Nbea deletion affects postsynaptic currents in cultured knockout neurons and heterozygous brain slices.

(a) Representative continuous recordings of pharmacologically isolated excitatory miniature postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) from cultured hippocampal neurons of wild-type (upper trace, +/+) and knockout (lower trace, −/−) mice in presence of TTX (0.5 μM) and bicuculline (5 μM). (b) For quantitative analysis of interevent intervals, amplitudes, rise and decay times, data from 80–160 individual mEPSCs were averaged per cell, and compared in 15–16 cells from at least three animals per genotype. (c) Representative recordings of inhibitory miniature postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) from cultured neurons were performed in the presence of TTX (0.5 μM) and CNQX (10 μM). (d) Evaluation of mIPSCs included the same parameters as for mEPSCs (b). (e–j) Exemplary continuous recordings (e,h) and fitted current traces from 80 single events (f,i) of isolated mEPSCs (e,f) and mIPSCs (h,i) from acute brain slices of wild-type (+/+) and heterozygous (+/−) Nbea mice. (g,j) Statistical analysis of interevent intervals, amplitudes, rise and decay times for mEPSCs (g) and mIPSCs (j) recorded from layer 5 pyramidal neurons of the somatosensory cortex, and quantitatively compared in 14–19 cells from at least four animals per genotype. All data are means±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, NS, not significant.

In contrast, recordings of mIPSCs from cultured neurons in presence of TTX and CNQX (Fig. 4c) failed to detect differences in rise and decay times (Fig. 4d), consistent with their aspinous nature. The altered interevent intervals and amplitudes of mIPSCs (Fig. 4d), in turn, are in agreement with our earlier recordings in the brainstem28.

To ensure specificity of these recorded defects, we next explored whether similar impairments were present in adult heterozygous mice. Pharmacologically isolated mEPSCs and mIPSCs were recorded from layer 5 pyramidal neurons, and fitted for analysis (Fig. 4e,f,h and i). We found that the interevent intervals of excitatory and inhibitory minis were increased significantly in heterozygous mutants by about 42% (mEPSCs, Fig. 4g) and 61% (mIPSCs, Fig. 4j), respectively (mEPSCs: Nbea+/+: 0.42 ±0.05s, n=15 cells per 4 mice; Nbea+/−: 0.60 ±0.07s, n=19 cells per 4 mice; P=0.038; mIPSC: Nbea+/+: 0.38 ±0.03s, n=17 cells per 7 mice; Nbea+/−: 0.61 ±0.08s, n=13 cells per 7 mice; P=0.005). These differences are less pronounced compared with cultured neurons lacking both alleles, but the rise time of mEPSCs was also faster in heterozygous animals (Fig. 4g, third panel, Nbea+/+: 1.59±0.1ms, n=15 cells per 4 mice; Nbea+/−: 1.32±0.07ms, n=19 cells per 4 mice; P=0.032), demonstrating that the data from brain slices are consistent with our observations in cultures.

Although the charge transfer of excitatory and inhibitory input per time was lower in mutants (Supplementary Fig. S3), the overall relation of excitation to inhibition remained remarkably stable (Supplementary Fig. S3). Thus, our electrophysiological results support the notion that excitatory/inhibitory balance is a critical parameter for neurons, and that the changed ratio of morphologically identified PSD-95 versus gephyrin-positive contacts (Fig. 3l) may reflect compensatory alterations induced by the loss of spinous synapses.

Presynaptic and postsynaptic effects of Nbea

Reduced numbers of spines (Figs 1 and 2), altered postsynaptic organization (Fig. 3), and pre- and postsynaptic functional impairments (Fig. 4) are consistent with the idea that Nbea acts upstream in the trafficking of synaptic components10,28. As the actin cytoskeleton has a critical role in modulating the function of pre- and postsynaptic terminals5,35, we tested whether actin distribution is altered in Nbea mutants.

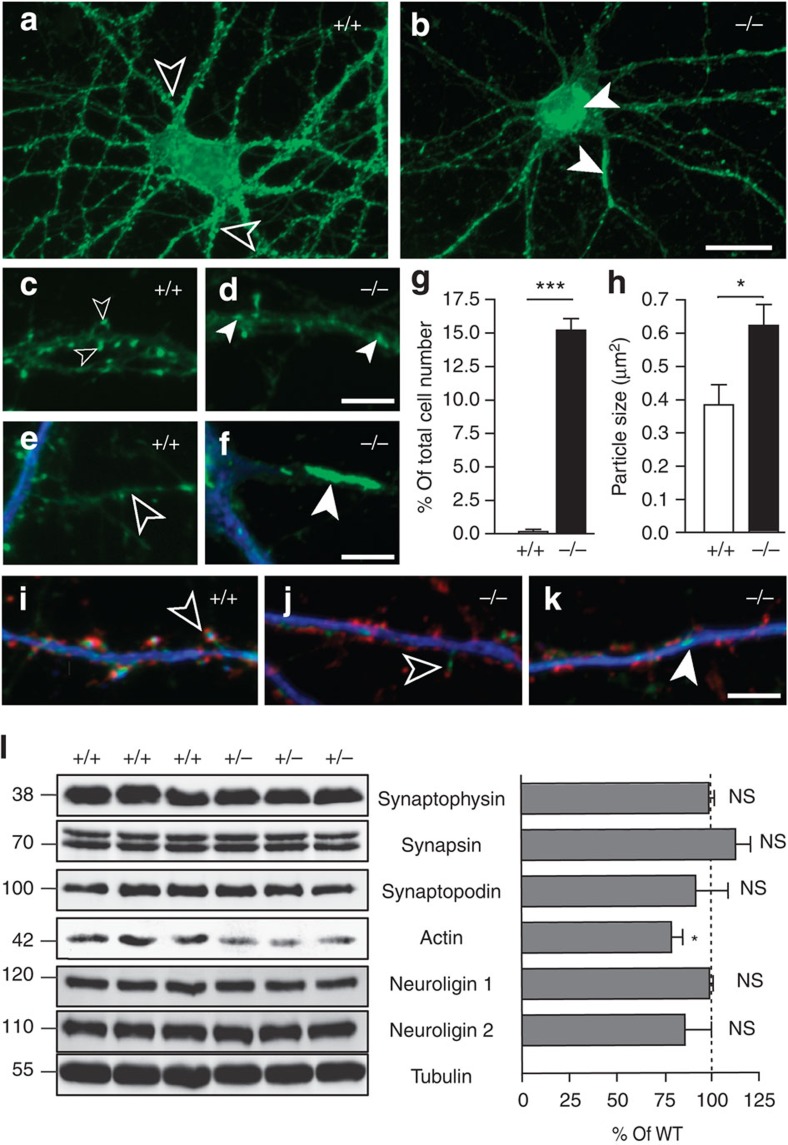

While wild-type neurons displayed synaptically enriched actin (Fig. 5a,c and e) as expected2,5, knockouts exhibited a change in the subcellular distribution of actin (Fig. 5b,d and f). Although actin could be found in some of the few mutant spines (Fig. 5j), it mostly accumulated in large clusters in the cell bodies, dendritic shafts and in axons (filled arrowheads in Fig. 5b,f and k). Controls showed most actin punctae at spine synapses (open arrowheads in Fig. 5a,c and i). Quantification of neurons containing accumulated actin (Fig. 5g) and measurement of the size of actin clusters (Fig. 5h) revealed significant increases in Nbea-deficient cultures (cells with accumulated actin: Nbea+/+: 0.16±0.16%, n=3 cultures; Nbea−/−: 15.22±0.86%, n=3 cultures; P<0.0001; actin cluster size in Nbea+/+: 0.38±0.06 μm2, n=1501 clusters per 3 cultures; Nbea−/−: 0.62±0.0.06 μm2, n=3040 clusters per 3 cultures; P=0.0168). Correspondingly, we observed a larger number of cortical neurons with prominent actin immunoreactivity over their somata in heterozygous Nbea mice (Supplementary Fig. S4), albeit this difference was less pronounced than in cultures. Moreover, quantitative immunoblots of heterozygous brain tissue revealed a significant 21% reduction of actin protein (Fig. 5l; P=0.0206), suggesting that the retention of filaments negatively regulated expression.

Figure 5. Distribution of actin depends on Nbea.

(a,b) Overview of representative images of hippocampal neurons from Nbea wild-type (+/+) and KO (−/−) cultures at DIV21 incubated with fluorochrome-labelled phalloidin (green). Large clusters of F-actin are seen in the somata and soma-near neurites of mutant neurons (filled arrowheads), whereas control cells show mostly a punctate-like distribution of actin along the dendrites (open arrowheads). (c,d) High magnification images show spine-bearing dendrites. Open arrowheads point to actin labelling in spines, filled arrowheads point to actin signals on the dendritic shaft. (e,f) Co-labelling with MAP2 (blue) to distinguish between dendritic (MAP2-positive) and axonal (MAP2-negative) processes. Wild-type axons contain only discrete actin staining (e, open arrowhead), while F-actin accumulated in large clusters of knockout axons (f, filled arrowhead). (g,h) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of neurons containing multiple F-actin clusters in the cell body (g), and the average size of 1,500–3,000 F-actin clusters in cells (h) of three independent cultures of wild-type (+/+) and knockout (−/−) mice at DIV21. (i–k) Immunocytochemistry of spine-bearing dendrites from Nbea wild-type (+/+) and KO (−/−) neurons at DIV21 incubated with phalloidin (green) and counterstained against synapsin (red) and MAP2 (blue). Open arrowheads point to actin-enriched spines and filled arrowheads to actin clusters in dendritic shafts. (l) Representative immunoblots of brain lysates from adult wild-type and heterozygous littermate mice loaded in triplicates, and quantification of different synaptic proteins normalized to tubulin. All data are means±s.e.m. *P<0.05, ***P<0.0001 and NS, =not significant. Scale bars, 20 μm in a, b, 5 μm in c–f and 5 μm in i–k.

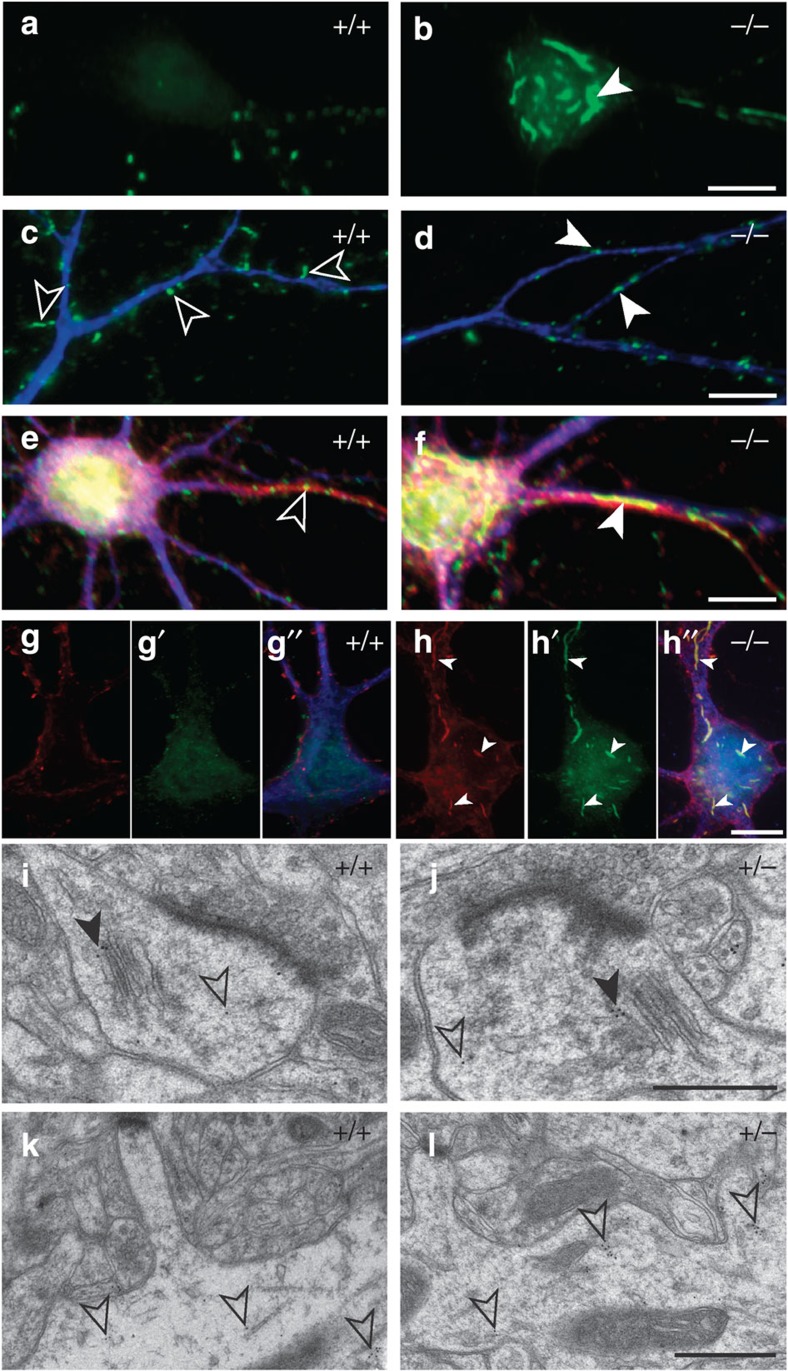

To explore if Nbea affected actin-dependent trafficking of postsynaptic proteins, we finally investigated the distribution of synaptopodin, a spine-associated protein36 with actin-bundling activity37. Whereas its protein levels appeared unchanged (Fig. 5l), synaptopodin accumulated in large clusters in cell bodies of Nbea-deficient neurons (arrowhead in Fig. 6b; wild-type cell bodies do not contain synaptopodin36, Fig. 6a). Although presence of classical spine apparatus in cultured neurons is controversial30, we saw prominent synaptopodin staining at dendritic spines of wild-type neurons (open arrowheads in Fig. 6c), consistent with earlier reports32. In mutant dendrites, however, synaptopodin primarily occurred in clusters within the shaft (filled arrowheads in Fig. 6d). Supporting the additional presence of synaptopodin in cisternal organelles of the axonal initial segment38, we observed discrete synaptopodin-positive punctae in axons of controls (Fig. 6e). Knockout axons, however, contained large clusters of accumulated synaptopodin (Fig. 6f).

Figure 6. Deletion of Nbea leads to mislocalization of the actin-associated protein synaptopodin.

(a,b) Somata of wild-type (+/+) and Nbea-deficient (−/−) hippocampal neurons at DIV21 stained against synaptopodin (green, filled arrowhead points to perinuclear clusters of synaptopodin only seen in knockouts). (c,d) Wild-type and mutant dendrites are double labelled against synaptopodin (green) and MAP2 (blue). Synaptopodin immunoreactivity is mostly seen associated with spines of wild-type dendrites (c, open arrowheads), but concentrated in the dendritic shaft in knockout neurons (d, filled arrowheads). (e,f) In Nbea-deficient neurons, enriched synaptopodin clusters also occur in soma-near segments of axonal processes (f, filled arrowhead), while only small axonal punctae are seen in control axons (e, open arrowhead). Axons were identified by absence of MAP2 and co-labelling with calnexin (red). (g,h) Co-staining of wild-type (g,g′,g′′) and Nbea knockout (h,h′,h′′) neurons with Alexa488-phalloidin (g′,h′, green) and antibodies against synaptopodin (g, h, red) and MAP2 (blue in the merged images) shows almost complete overlap of actin and synaptopodin that are retained in clusters in the somata and soma-near processes of KO neurons (filled arrowheads in h, h′, h′′). (i–l) Postembedding immunogold labelling of synaptopodin directly at the spine apparatus (filled arrowheads) and at spine-near dendritic locations (open arrowheads) in neocortical tissue of wild-type (i,k, +/+) and Nbea heterozygous (j,l, +/−) mice. Scale bars, 10 μm in a–h, 500 nm in i–j and 250 nm in k,l.

As the pattern of accumulated actin and synaptopodin looked similar, we next performed double-labelling experiments: cell bodies from controls did not show relevant staining for the two proteins (Fig. 6g), but Nbea-deficient neurons revealed an almost complete overlap of actin and synaptopodin clusters (Fig. 6h). This indicates that the proposed actin association of synaptopodin might not only be important in renal podocytes37 but also in neurons32. Therefore, we performed postembedding immunogold labelling of synaptopodin in neocortical tissue of wild-type and Nbea heterozygous (Fig. 6i–l) animals. We observed that in addition to the previously described association with the spine apparatus (filled arrowheads, Fig. 6i,j; refs 36,39), synaptopodin is also present at numerous other dendritic locations (open arrowheads, Fig. 6i–l). This raises the possibility that Nbea has a more general role in regulating the F-actin network at synapses.

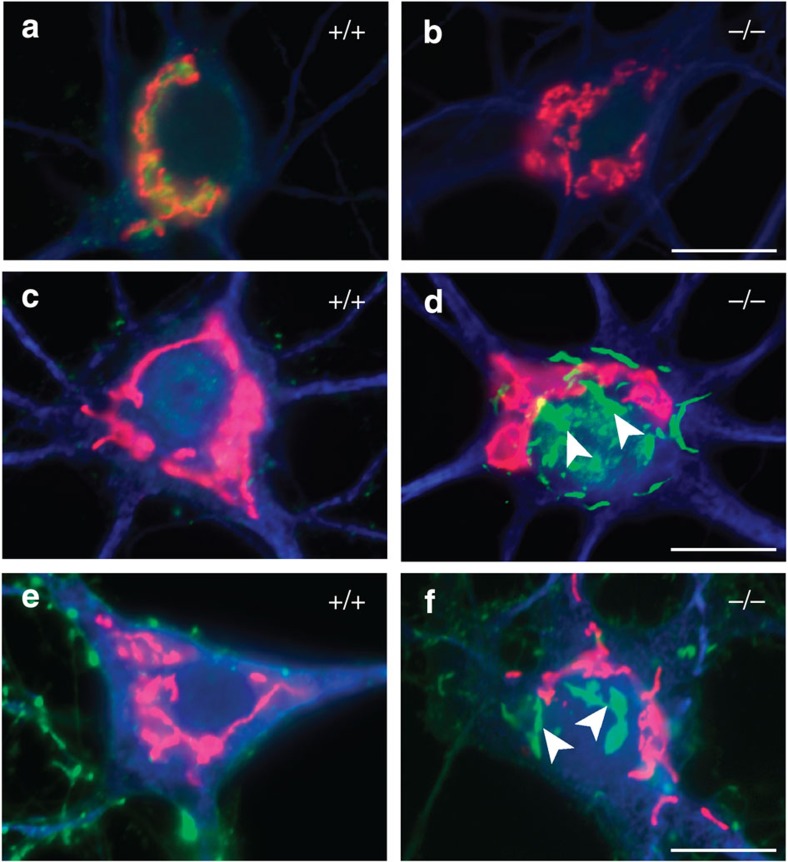

As Nbea is localized to the trans-Golgi network10 and the perinuclear pattern of accumulated synaptopodin and actin in mutants is reminiscent of a Golgi-near localization (Figs 5 and 6), we finally addressed their spatial relation in cultures. We first confirmed by co-labelling of Nbea with the marker proteins GM130 (Fig. 7a) and syntaxin 6 (data not shown) that Nbea is present in tubulovesicular organelles adjacent to the Golgi apparatus in controls, and that the Golgi was still present in knockouts (Fig. 7b). Co-labelling of synaptopodin with the same proteins revealed that the perinuclear accumulation of synaptopodin in Nbea mutants is spatially close to but not overlapping with the Golgi (Fig. 7d). The same staining in controls confirmed absence of synaptopodin from somata (Fig. 7c). Accordingly, co-labelling of actin with the marker protein GM130 in control (Fig. 7e) and mutants (Fig. 7f) resembled closely the synaptopodin/GM130 distribution (Fig. 7c,d). As the distribution of synaptopodin/GM130 and actin/GM130 in cell bodies of knockouts was similar to the Nbea/GM130 localization in controls, their respective pathways may intersect in the trans-Golgi compartment. These data provide the first mechanistic cues how Nbea may affect trafficking of synaptic components, and why pre- and postsynaptic defects are observed in Nbea-mutant mice.

Figure 7. Synaptopodin and actin are retained near the trans-Golgi network in Nbea-mutant neurons.

(a) In wild-type (+/+) hippocampal neurons at DIV21, a large amount of Nbea (green) is localized near the trans-Golgi network revealed by the marker protein GM130 (red). Additional co-labelling against MAP2 (blue) identifies dendrites and somata. (b) Control experiment showing co-staining with the same antibodies in Nbea-deficient (−/−) hippocampal neurons. (c) Co-labelling of synaptopodin (green) with GM130 (red) and MAP2 (blue) fails to detect visible amounts of synaptopodin in somata of wild-type neurons. (d) In contrast, deletion of Nbea leads to ectopic accumulation of prominent clusters of synaptopodin (filled arrowheads) in the cell body near the trans-Golgi network. (e,f) Co-labelling of actin (green) with GM130 (red) and MAP2 (blue) reveals a comparable pattern to the synaptopodin/GM130 distribution (c, d), showing ectopic accumulation of actin clusters in the cell body of Nbea-deficient neurons (f, filled arrowheads). Scale bars, 10 μm in a–f.

Discussion

The phenotype of Nbea deficiency in mature neurons demonstrated here consists of an impaired development and function of spinous synapses (Figs 1,2 and 4), a concomitant shift of PSD-95 clusters to the dendritic shaft (Fig. 3) and an ectopic accumulation of F-actin and synaptopodin (Figs 5,6,7). These results were surprising because previous analyses in foetal mice emphasized presynaptic defects28,29.

As spinous synapses are scarce before birth in altricial animals40 and NMJs lack a neuronal postsynaptic partner, however, the effect on spinous synapses could not be detected by the earlier studies. Nevertheless, Medrihan et al.28 reported a slight decrease in mini amplitudes, which pointed to additional postsynaptic impairments. Our current data derived from two standard models for studying synaptic function confirm the postsynaptic effect on peak amplitudes of mini events. In addition, we found shorter rise times of mEPSCs in mutants (Fig. 4), which are indicative of shorter spines or aspinous neurons30,34. Changes in miniature postsynaptic current (mPSC) kinetics were not observed earlier28, again consistent with the lack of spinous synapses in the foetal brainstem.

While all investigations agree that Nbea is not required for the establishment of synapses in general, our previous study reported a reduced area density of asymmetric synapses in brainstem28, whereas we show here a specific reduction of spinous synapses with unchanged total numbers of asymmetric contacts (Figs 1 and 2). These results could be explained by a more dramatic delay of synaptogenesis in homozygous compared with heterozygous mice (Fig. 2). Such view is supported by diminished levels of a subset of presynaptic vesicle proteins in foetal Nbea−/− brainstem28, which is not detected in adult heterozygous brains (Fig. 5). One possible interpretation holds that reduced levels of Nbea predominantly affect postsynaptic processes such as spine development, whereas complete lack prevents formation of many contacts by interfering additionally with presynaptic processes.

Alternatively, the results might reflect a specific delay in synapse development in the brainstem that is compensated in higher brain regions (neocortex, Fig. 2), for example, by overlapping expression with related proteins41,42. Such view is supported by analysis of cultured hippocampal knockout neurons that reproduced the effect on spinous synapses (Fig. 1) and the electrophysiologically observed impairments (Fig. 4). However, all currently available data together convincingly agree that Nbea has important roles in pre- and postsynaptic processes.

The pre- and postsynaptic effects of deleting Nbea in mice indicate that the pleiotropic phenotype is in agreement with a function in the trafficking of pre- and postsynaptic components10,28, but its immediate targets remain unclear. We demonstrate that loss of Nbea interferes with the normal distribution of F-actin at synapses (Fig. 5), an important result because actin is the major cytoskeletal component of presynaptic terminals and dendritic spines2,43,44,45. Numerous studies showed that actin has a pivotal role in the formation, shape and motility of dendritic spines5,44. In addition, modulation of actin dynamics drives changes in spines that are associated with alterations in synaptic strength1,2,4. Finally, actin is involved in organizing the postsynaptic density, anchoring postsynaptic receptors, facilitating the trafficking of synaptic cargos and localizing the translation machinery5,43,44.

As our finding that Nbea might act on the actin filament organization was unexpected, we reassessed its molecular architecture (Supplementary Fig. S5). Interestingly, two additional WD repeats may be present in Nbea that possibly allow to assign a propeller structure. Many actin-binding proteins such as Arp2/3 complex (p40) and coronins contain such propeller domains and localize to dendritic spines where they organize the actin network43,46,47, raising the possibility that Nbea also binds to or regulates the assembly of F-actin.

If Nbea was involed in initiation or maintenance of F-actin at synapses, deletion could cause destabilization of the actin network and lower numbers of dendritic spines43. Such a role is further supported by our observation that Nbea is responsible for a normal distribution of synaptopodin, an actin- and α-actinin-associated protein involved in the RhoA pathway37,48,49,50, because it co-localized with ectopically accumulated F-actin in KO neurons (Figs 6 and 7). Previously, a possible interaction between the plant BEACH protein SPIRRIG and the actin cytoskeleton was only inferred from phenotype similarities with mutants of the ARP2/3 complex51.

Synaptopodin was characterized as an essential component of the spine apparatus39, and functionally linked to synaptic plasticity32,36. As deletion of synaptopodin resulted into a lack of spine apparatuses but not of spines themselves36, it can be hypothesized that the effect of Nbea on synaptopodin is secondary to its effect on actin. One possibility is that actin filaments normally serve as a template for synaptopodin at dendritic spines37,48,49, whereas in Nbea mutants, synaptopodin simply associates with the actin ectopically retained in somata and processes (Fig. 6). The effect of Nbea on actin most likely starts at the level of the trans-Golgi network because actin and synaptopodin accumulate in Nbea-mutant neurons at a location where Nbea is normally present (Fig. 7, and ref. 10). The link to the actin cytoskeleton together with its ability to associate with Golgi-near endomembranes10 provides new evidence that Nbea has a role in trafficking of proteins and membranous organelles to both pre- and postsynaptic compartments. Such a role was also demonstrated for a related BEACH protein, BCHS, in Drosophila52, and normal growth and morphological plasticity of spines are predicted to depend on Golgi-derived cargo organelles and endosomal membrane trafficking53,54.

In recent years, it has become evident that many psychiatric and neurological disorders are accompanied by alterations in spines6,7,8, and various memory disorders involve defects in the regulation of actin43. Human genetic studies have linked heterozygous disruptions of the Nbea gene to idiopathic cases of non-familial autism18,19,20,21, and defects in spinous synapses are found in mouse models of other autism candidate molecules. For example, mutations in the postsynaptic protein Shank3 revealed reductions in spine density and mEPSCs55, reminiscent of the changes seen here. Importantly, our present study shows for the first time a morphological and electrophysiological phenotype of Nbea-haploinsufficient neurons. Even moderate alterations of Nbea abundance or activity have consequences at the cellular level, which may then manifest at the organismic level in disorders such as autism.

Methods

Primary neurons

All experiments involving mice were performed in accordance with local institutional and government regulation for animal welfare. Cultures were prepared from individual hippocampi of wild-type and Nbea KO mouse embryos (E17), digested with 0.25% trypsin and triturated mechanically. Neurons were seeded onto poly-L-lysin-coated coverslips at low density (50–100 cells mm−2), and placed upside down above a layer of astrocytes containing N2.1 medium56. Neurons were transfected with pMH4-SYNtdimer2-RFP (T. Oertner, Basel, Switzerland) on DIV4 by calcium phosphate transfection57. Immunocytochemistry: neurons were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/4% sucrose for 10 min, washed with PBS and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton-X100/PBS for 10 min. After blocking in 5% normal goat serum (NGS)/PBS for 30 min, incubation with primary antibodies followed overnight at 4 °C: rb-anti-pan-synapsin (1:500, E028, T. Südhof, Stanford University), ms-anti-synapsin (1:500), ms-anti-PSD-95 (1:500), ch-anti-MAP2 (1:10,000), ms-anti-calnexin (1:1,000, all from Abcam), ms-anti-vGlut1 (1:500), rb-anti-vGlut2 (1:500), ms-anti-gephyrin (1:500), rb-anti-neurobeachin (1:1,000, all from Synaptic Systems), ms-anti-syntaxin6 (1:500), ms-anti-GM130 (1:1,000, both from BD Transduction Laboratories), diluted in 5% NGS/PBS. Rabbit-anti-synaptopodin (Sigma) was applied according to ref. 32. After washing, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies Alexa488 goat-anti-rabbit, Alexa488 goat-anti-mouse IgG, Alexa647 goat-anti-chicken IgG (Invitrogen), Cy3-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit, goat-anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immuno Research), all diluted 1:500 in 5% NGS/PBS for 1 h at RT. To visualize F-actin, cells were incubated with Alexa-Fluor488-Phalloidin (1:100, Invitrogen) for 1 h at RT. After final washes, coverslips were embedded in mounting medium (Dako). Quantitative image analysis: cultures were observed with an Axioskop2 using a 40× Plan Neofluar or 63× Axoplan oil immersion objective, and an AxioCam MRm digital camera (Zeiss). The number of immunoreactive punctae was determined per 10 μm dendrite length. The number of overlapping presynaptic and postsynaptic punctae was quantified, and the probability of co-localization was calculated58 as: [(number of juxtaposed punctae)2/(number of presynaptic punctae×number of postsynaptic punctae)]. The number of neurons with actin accumulations was determined with >300 cells per coverslip and is given as % of the total cell number. To determine the cluster size of actin signals, images were thresholded manually and analysed using the 'analyse particles' function of ImageJ software (NIH). Confocal imaging of dendritic spines was carried out with a laser scanning microscope (Leica SP2) and 63× oil immersion objective to take image stacks of 0.2 μm distance. Spine dimensions were determined in maximum projections using ImageJ. Two-dimensional maximum projections were imported into Imaris software (Bitplane), and three-dimensional surface-rendered images were reconstructed using the FilamentTracer function. All figures were prepared with Adobe Illustrator software. Scale bars given on all figures are identical for the respective pairs of images from control and mutant samples.

Light microscopy of mouse brains

Anesthetized adult mice were perfusion-fixed with 70 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PB (37 °C) and postfixed for 1 h at RT. After dissection, brains were cryoprotected in 25% sucrose/0.1 M PB overnight. Immunhistochemistry: 30 μm free-floating cryosections were treated with 1% Triton X-100 for 15 min and blocked with 50% NGS/PBS at 4 °C overnight, followed by primary antibody labelling with rb-anti-neurobeachin (1:500, SynapticSystems) or rb-anti-actin (1:100, Sigma) in buffer (0.1% Triton X-100, 50% NGS in PBS) at 37 °C for 4 h. Secondary antibody goat-anti-rabbit (1:100, Covance) was applied in buffer for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by rb-PAP (1:400, Sternberger) for 1 h at 37 °C. Visualization was done with diaminobenzidine (0.05% w/v), H2O2 (0.005% v/v) and NiCl2 (0.15% w/v). Stained sections were mounted with 0.5% gelatine, and embedded with Entellan. Nissl staining with 0.1% cresylviolet is described in Supplementary Methods. Image acquisition: stainings were documented with an Axioskop2 microscope and a digital camera AxioCam MRm, using a 20× objective for grey value analysis, and for quantifications of cells. A 63× oil immersion objective was used for high magnification images. The mean grey value was determined using the 'histogram analysis' of ImageJ.

Electron microscopy

Brains from mice and neuronal cultures were embedded in epon resin (Electron Microscopy Science). Brain tissue: anesthetized mice were transcardially perfused with 70 ml of 2% glutaraldehyde (Serva) and 2% paraformaldehyde (Merck) in 0.1 M PB at 37 °C, and postfixed at 4 °C overnight. Blocks of cortical tissue were contrasted in 1% OsO4 for 2 h at RT. Following washes with dH2O and dehydrating, tissue was incubated with propylene oxide (EMS) for 45 min, infiltrated with propylene oxide/epon (1:1) for 1 h, in pure epon overnight, and hardened at 60 °C for 24 h. Neuronal cultures: embedding of neurons on coverslips followed the same protocol as for brains, applying reduced incubation times. Glass coverslips were finally placed on epon-filled moulds, and after hardening, removed by dipping in boiling water and liquid nitrogen. Contrasting of thin sections from brains and cultures was done on Formvar-coated copper grids with a saturated solution of 12% uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Immunogold labelling: staining steps were carried out on Formvar-coated gold grids in a humidified atmosphere. Ultrathin sections from brain tissue were etched with 10% periodic acid and 10% sodium meta-periodate for 14 min each, and placed on droplets of blocking solution (0.5 M glycine in TBS) for 15 min, followed by drops of 20% NGS in TBS for 20 min. Tissue sections were incubated with rb-anti-synaptopodin (1:50, Sigma) in 10% NGS/TBS at 37 °C for 3 h. After washes on 20% NGS/TBS and EMIX (0.9% NaCl, 0.1% BSA in 0.05 M TB), a 10-nm gold-conjugated secondary goat-anti-rabbit antibody (1:10, EMS) was applied at RT for 2 h. Following washes in EMIX and dH2O, sections were contrasted with uranyl and lead citrate. Ultrastructural analysis: samples were investigated with a transmission electron microscope (Libra 120, Zeiss) at 80 kV, and images taken with a 2048×2048 CCD camera (Tröndle). For brain tissue, two image series from the somatosensory cortex of each animal were examined at 5000× primary magnification. Each series included images from all cortical layers, and was composed of about 17 multiple image alignment (MIA) pictures. Each MIA picture, in turn, was assembled from four adjacent images, representing an area of 100 μm2. MIA composition and analysis were carried out with ITEM software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions). Synapse morphology: asymmetric (type 1) synapses were defined as contacts with a visible synaptic cleft, a distinct postsynaptic density (PSD) and at least three synaptic vesicles, whereas symmetric (type 2) contacts showed an inapparent PSD and contained pleiomorphic vesicles. Axo-spinous contacts were identified as small dendritic protrusions (maximum length 1 μm) with a visible PSD opposed to a presynaptic terminal. Three synaptic populations were quantified as area densities: number of total asymmetric and symmetric synapses, and number of axo-spinous contacts. In addition, one randomly chosen synapse was analysed on each MIA picture at a higher zoom level (200%) to quantify the presynaptic terminal area, number of synaptic vesicles per terminal area and length of the PSD. Synaptic cleft width was determined from three synapses per MIA by six repeated measurements.

Electrophysiological recordings

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed on cultured hippocampal neurons (DIV17-20), and on layer 5 pyramidal cells in acute slices from the somatosensory cortex of mice (P14-P16). mPSCs were measured under 500 nM tetrodotoxin (TTX, Tocris) in combination with either 5 μM 1(S),9(R)-(–)-Bicuculline methiodide (Bicuculline, Sigma) for pharmacologically isolated excitatory recordings, or 10 μM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX, Sigma) for inhibitory recordings. Data acquisition and analysis was performed using Patchmaster V2X42 and Fitmaster V2X32 software (HEKA), MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft) and Microsoft Excel. For each cell, the amplitude, rise time (10–90%), decay time (time constant of a monoexponential fit) and the interevent interval of at least 80 individual mPSCs were determined (Supplementary Methods).

Biochemical analysis

Forebrains of embryonic (E17) and adult mice were homogenized as described previously28. Lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and 4–15% precast gradient gels (Biorad). Nitrocellulose blots (GE Healthcare) were probed with the following antibodies: rb-anti-neurobeachin (1:5,000, Synaptic Systems), a new rb-anti-Nbea antibody produced against peptide YNRWRNSEIRC (3041, 1:1,000, Eurogentec), ms-anti-synaptophysin (1:1,000, DAKO), ms-anti-synapsin1a/b (1:10,000, Synaptic Systems), rb-anti-synaptopodin (1:2,000, Sigma), rb-anti-actin (1:500, Sigma), ms-anti-neuroligin1 (1:1,000, Synaptic Systems), rb-anti-neuroligin2 (1:5,000, Synaptic Systems), rb-anti-tubulin (1:20,000, Sigma), followed by HRP-coupled secondary antibodies (goat-anti-mouse/rabbit IgG, Biorad, 1:20,000). Proteins were visualized using a chemiluminescence kit (Millipore), and DC Science Tec detection system (DC Science Tec). Intensities of immunolabelled bands were quantified and normalized against tubulin using the 'GelAnalyzer function' of ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means±s.e.m. Statistical significance was tested with a two-tailed Student's t-test using Prism software (GraphPad Software), assuming Gaussian distribution. Results were denoted statistically significant when P-values were <0.05 (significance levels as indicated in figure legends). Exact P-values and the number (n) of samples/repeats are given in the Results and figure legends of the respective experiments.

Author contributions

K.N., D.B., J.B., G.B., I.W., C.R. and A.R. collected and analysed data, and critiqued the manuscript. M.W.K. provided the neurobeachin knockout mouse line. K.N., A.R. and M.M. conceived and directed the project, and M.M. wrote the manuscript.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Niesmann, K. et al. Dendritic spine formation and synaptic function require neurobeachin. Nat. Commun. 2:557 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1565 (2011).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S5 and Supplementary Methods

Acknowledgments

We thank J.R. Wolff for advice on electron microscopic analysis, K. Kerkhoff and D. Aschhoff for technical assistance, and H. Blum for help with Imaris software and figure preparation. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grant number SFB 629-TP B11 (M.M.).

References

- Bourne J. N. & Harris K. M. Balancing structure and function at hippocampal dendritic spines. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 47–67 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani L. A. & Goda Y. Actin in action: the interplay between the actin cytoskeleton and synaptic efficacy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 344–356 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M. J. & Ehlers M. D. Organelles and trafficking machinery for postsynaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29, 325–362 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez V. A. & Sabatini B. L. Anatomical and physiological plasticity of dendritic spines. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 79–97 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost N. A., Kerr J. M., Lu H. E. & Blanpied T. A. A network of networks: cytoskeletal control of compartmentalized function within dendritic spines. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20, 578–587 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. C. & Koleske A. J. Mechanisms of synapse and dendrite maintenance and their disruption in psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 33, 349–378 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpied T. A. & Ehlers M. D. Microanatomy of dendritic spines: emerging principles of synaptic pathology in psychiatric and neurological disease. Biol. Psychiatry 55, 1121–1127 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P., Cahill M. E., Jones K. A., VanLeeuwen J. E. & Woolfrey K. M. Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 285–293 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volders K., Nuytens K. & Creemers J. W. The autism candidate gene neurobeachin encodes a scaffolding protein implicated in membrane trafficking and signaling. Curr. Mol. Med. 11, 204–217 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. Neurobeachin: a protein kinase A-anchoring, beige/Chediak-higashi protein homolog implicated in neuronal membrane traffic. J. Neurosci. 20, 8551–8565 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. W., Howson J., Haller E. & Kerr W. G. Identification of a novel lipopolysaccharide-inducible gene with key features of both A kinase anchor proteins and chs1/beige proteins. J. Immunol. 166, 4586–4595 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza N., Vallier L. G., Fares H. & Greenwald I. SEL-2, the C. elegans neurobeachin/LRBA homolog is a negative regulator of lin-12/Notch activity and affects endosomal traffic in polarized epithelial cells. Development 134, 691–702 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamloula H. K. et al. Rugose (rg), a Drosophila A kinase anchor protein, is required for retinal pattern formation and interacts genetically with multiple signaling pathways. Genetics 161, 693–710 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wech I. & Nagel A. C. Mutations in rugose promote cell type-specific apoptosis in the Drosophila eye. Cell Death Differ. 12, 145–152 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogl G. et al. Crystal structure of the BEACH domain reveals an unusual fold and extensive association with a novel PH domain. EMBO J. 21, 4785–4795 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelyeva L., Sagulenko E., Schmitt J. G. & Schwab M. The neurobeachin gene spans the common fragile site FRA13A. Hum. Genet. 118, 551–558 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D. J. et al. The neurobeachin gene (Nbea) identifies a new region of homology between mouse central chromosome 3 and human chromosome 13q13. Mamm. Genome 10, 1030–1031 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castermans D. et al. SCAMP5, NBEA and AMISYN: three candidate genes for autism involved in secretion of large dense-core vesicles. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 1368–1378 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castermans D. et al. The neurobeachin gene is disrupted by a translocation in a patient with idiopathic autism. J. Med. Genet. 40, 352–356 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. et al. Molecular genetic delineation of a deletion of chromosome 13q12—>q13 in a patient with autism and auditory processing deficits. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 98, 233–239 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele M. M., Al-Adeimi M., Siu V. M. & Fan Y. S. Brief report: a case of autism with interstitial deletion of chromosome 13. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 31, 231–234 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persico A. M. & Bourgeron T. Searching for ways out of the autism maze: genetic, epigenetic and environmental clues. Trends Neurosci. 29, 349–358 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi H. Y. Postnatal neurodevelopmental disorders: meeting at the synapse? Science 302, 826–830 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missler M. et al. Alpha-neurexins couple Ca2+ channels to synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Nature 423, 939–948 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrihan L. et al. Early defects of GABAergic synapses in the brain stem of a MeCP2 mouse model of Rett syndrome. J. Neurophysiol. 99, 112–121 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqueaux F. et al. Neuroligins determine synapse maturation and function. Neuron 51, 741–754 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. & Rosenmund C. MeCP2 controls excitatory synaptic strength by regulating glutamatergic synapse number. Neuron 56, 58–65 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrihan L. et al. Neurobeachin, a protein implicated in membrane protein traffic and autism, is required for the formation and functioning of central synapses. J. Physiol. 587, 5095–5106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y. et al. Neurobeachin is essential for neuromuscular synaptic transmission. J. Neurosci. 24, 3627–3636 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal M. Dendritic spines, synaptic plasticity and neuronal survival: activity shapes dendritic spines to enhance neuronal viability. Eur. J. Neurosci. 31, 2178–2184 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa M., Bundman M. C., Greenberger V. & Segal M. Morphological analysis of dendritic spine development in primary cultures of hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 15, 1–11 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachos A. et al. Synaptopodin regulates plasticity of dendritic spines in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 1017–1033 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M. A. et al. Miniature neurotransmission stabilizes synaptic function via tonic suppression of local dendritic protein synthesis. Cell 125, 785–799 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya R., Jiang J., Eisenthal K. B. & Yuste R. The spine neck filters membrane potentials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17961–17966 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colicos M. A., Collins B. E., Sailor M. J. & Goda Y. Remodeling of synaptic actin induced by photoconductive stimulation. Cell 107, 605–616 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deller T. et al. Synaptopodin-deficient mice lack a spine apparatus and show deficits in synaptic plasticity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10494–10499 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K. et al. Synaptopodin regulates the actin-bundling activity of alpha-actinin in an isoform-specific manner. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1188–1198 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas Orth C., Schultz C., Muller C. M., Frotscher M. & Deller T. Loss of the cisternal organelle in the axon initial segment of cortical neurons in synaptopodin-deficient mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 504, 441–449 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deller T., Merten T., Roth S. U., Mundel P. & Frotscher M. Actin-associated protein synaptopodin in the rat hippocampal formation: localization in the spine neck and close association with the spine apparatus of principal neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 418, 164–181 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüz A. [Prenatal development and postnatal changes in the guinea pig cortex: microscopic evaluation of a natural deprivation experiment. I. Prenatal development]. J. Hirnforsch. 22, 93–111 (1981). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W. H., Shek K. F., Lee T. Y. & Chow K. L. An evolutionarily conserved nested gene pair - Mab21 and Lrba/Nbea in metazoan. Genomics 94, 177–187 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. et al. Identification and characterization of NBEAL1, a novel human neurobeachin-like 1 protein gene from fetal brain, which is up regulated in glioma. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 125, 147–155 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotulainen P. & Hoogenraad C. C. Actin in dendritic spines: connecting dynamics to function. J. Cell Biol. 189, 619–629 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada T. & Sheng M. Molecular mechanisms of dendritic spine morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 95–101 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korobova F. & Svitkina T. Molecular architecture of synaptic actin cytoskeleton in hippocampal neurons reveals a mechanism of dendritic spine morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 165–176 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcer H. I., Daugherty-Clarke K. & Goode B. L. The p40/ARPC1 subunit of Arp2/3 complex performs multiple essential roles in WASp-regulated actin nucleation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8481–8491 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetrecht A. C. & Bear J. E. Coronins: the return of the crown. Trends Cell Biol. 16, 421–426 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K. et al. Synaptopodin orchestrates actin organization and cell motility via regulation of RhoA signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 485–491 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremerskothen J., Plaas C., Kindler S., Frotscher M. & Barnekow A. Synaptopodin, a molecule involved in the formation of the dendritic spine apparatus, is a dual actin/alpha-actinin binding protein. J. Neurochem. 92, 597–606 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P. et al. Synaptopodin: an actin-associated protein in telencephalic dendrites and renal podocytes. J. Cell Biol. 139, 193–204 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saedler R., Jakoby M., Marin B., Galiana-Jaime E. & Hulskamp M. The cell morphogenesis gene SPIRRIG in Arabidopsis encodes a WD/BEACH domain protein. Plant J. 59, 612–621 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodosh R., Augsburger A., Schwarz T. L. & Garrity P. A. Bchs, a BEACH domain protein, antagonizes Rab11 in synapse morphogenesis and other developmental events. Development 133, 4655–4665 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maletic-Savatic M. & Malinow R. Calcium-evoked dendritic exocytosis in cultured hippocampal neurons. Part I: trans-Golgi network-derived organelles undergo regulated exocytosis. J. Neurosci. 18, 6803–6813 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. et al. Plasticity-induced growth of dendritic spines by exocytic trafficking from recycling endosomes. Neuron 52, 817–830 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peca J. et al. Shank3 mutant mice display autistic-like behaviours and striatal dysfunction. Nature 472, 437–442 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech S. & Banker G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2406–2415 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairless R. et al. Polarized targeting of neurexins to synapses is regulated by their C-terminal sequences. J. Neurosci. 28, 12969–12981 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. X., Tari P. K., She K. & Haas K. Neurexin-neuroligin cell adhesion complexes contribute to synaptotropic dendritogenesis via growth stabilization mechanisms in vivo. Neuron 67, 967–983 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S5 and Supplementary Methods