Abstract

Deficiency of the extracellular matrix molecule FRAS1, normally expressed by the ureteric bud, leads to bilateral renal agenesis in humans with Fraser syndrome and blebbed (Fras1bl/bl) mice. The metanephric mesenchyme of these mutants fails to express sufficient Gdnf, which activates receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signalling, contributing to the phenotype. To determine whether modulating RTK signalling may overcome the abnormal nephrogenesis characteristic of Fraser syndrome, we introduced a single null Sprouty1 allele into Fras1bl/bl mice, thereby reducing the ureteric bud's expression of this anti-branching molecule and antagonist of RTK signalling. This prevented renal agenesis in Fras1bl/bl mice, permitting kidney development and postnatal survival. We found that fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signalling contributed to this genetic rescue, and exogenous FGF10 rescued defects in Fras1bl/bl rudiments in vitro. Whereas wild-type metanephroi expressed FRAS1 and the related proteins FREM1 and FREM2, FRAS1 was absent and the other proteins were downregulated in rescued kidneys, consistent with a reciprocally stabilized FRAS1/FREM1/FREM2 complex. In addition to contributing to knowledge regarding events during nephrogenesis, the demonstrated rescue of renal agenesis in a model of a human genetic disease raises the possibility that enhancing growth factor signaling might be a therapeutic approach to ameliorate this devastating malformation.

Renal agenesis (RA) is detected in every 2×104 human births1 and sometimes occurs in multiorgan malformation syndromes.2–5 One such is Fraser syndrome (FS; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 219000), an autosomal-recessive disease also characterized by skin lesions resulting from embryonic blistering.6,7 One third of cases have bilateral RA, and most of the rest have unilateral RA with a contralateral hypodysplastic kidney.6,7 FRAS1 was the first gene found mutated in FS.8 It encodes an extracellular matrix protein that contains domains thought to interact with growth factors, thus modifying their actions.8–10 In skin, FRAS1 is associated with two homologous proteins called Fras1-related extracellular matrix protein 1 (FREM1) and FREM2.11–13 Other patients with FS have homozygous FREM2 mutations,14 and homozygous mutant Fras18,15 or Frem214 have both RA and embryonic hemorrhagic skin blisters. Heterozygous FRAS1 and FREM2 mutations have each been associated with unilateral RA16 and FREM1 heterozygosity with metopic craniosynostosis.17

Mutual inductions between ureteric bud and nephron precursors are required to initiate the metanephric kidney.18–20 The ureteric bud expresses Fras1 transcripts, and FRAS1 protein is immunodetected at the interface between ureteric bud epithelia and metanephric mesenchyme (MM).21 On the C57BL/6J background, homozygous blebbed mice (Fras1bl/bl; MGI:1856691) have highly penetrant RA.21 Lack of functional FRAS1 in Fras1bl/bl mice is caused by a premature stop codon (S2200×),8 and MMs undergo fulminant apoptosis8,21 associated with absent ureteric bud initiation from the mesonephric duct or failed ureteric bud progression to penetrate the MM.21 RA in Fras1bl/bl mice is accompanied by failure of MM to maintain full expression of glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor (Gdnf).21 In health, GDNF binds the rearranged during transfection (RET) receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK). This upregulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling, as manifest by the detection of phospho-ERK (pERK) in mesonephric duct/ureteric bud cells. This in turn contributes to driving the emergence of the bud and its arborization.22–24 Mutations of other genes leading to perturbed Gdnf expression or GDNF-activated pathways cause similar ureteric bud defects as found in Fras1bl/bl embryos.24 Addition of recombinant GDNF to explanted Fras1bl/bl nephrogenic fields stimulates ureteric bud growth into MM, which becomes molecularly induced.21 However, the extent to which even wild-type metanephroi develop in vitro is limited.

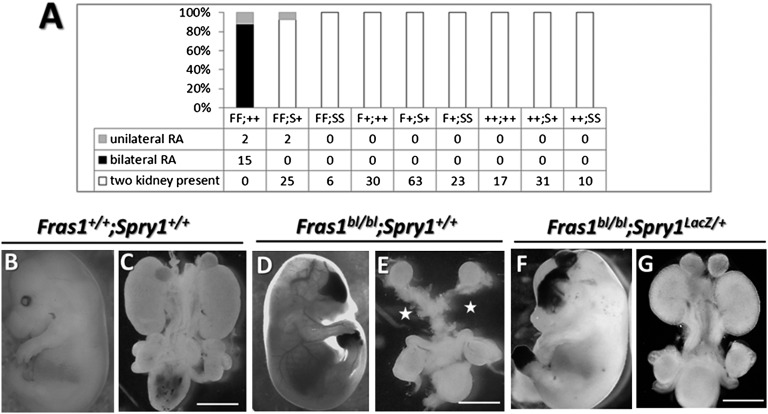

We hypothesized that if RTK signaling were experimentally upregulated in vivo, mature kidneys would be generated in Fras1bl/bl mice. Sprouty (SPRY) proteins inhibit RTK signaling and Spry1 transcripts are expressed in mesonephric duct and ureteric buds, where they downregulate ERK activation, thus preventing ectopic branching.25–27 We bred a Spry1 null allele (MGI:3832050)25 into Fras1bl mice maintained on a C57BL/6J background. Offspring (n=224) of parents, each heterozygous for Fras1bl and Spry1LacZ alleles, were autopsied between embryonic days (E)11 and E15 (Figure 1A). As expected, no RA or skin blisters were detected in Fras1+/+ or Fras1bl/+ embryos (Figure 1, B and C). Seventeen Fras1blbl embryos were wild-type at the Spry1 locus, and all had RA (88% bilateral and 12% unilateral) and hemorrhagic blistering (Figure 1, D and E). Twenty-seven Fras1bl/bl embryos carried a single Spry1LacZ allele, and 25 of them (93% of this genotype) had two kidneys (Figure 1, F and G); the other two embryos had unilateral RA (P<0.0001 by two-tailed Fisher exact test comparing any RA outcome between Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+ and Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ embryos). Although the mutant Spry1 allele facilitated the initiation of renal development, these Fras1blbl embryos still had blisters, consistent with FRAS1’s role in the skin: that is, maintenance of epidermal/dermal physical adhesion12 rather than facilitating growth factor signaling. Six Fras1bl/bl embryos were homozygous for Spry1LacZ, and none had RA; as reported for non-FS Spry1 null mice,26,27 they had duplex kidneys. Duplication was never observed in embryos carrying a single mutant Spry1 allele.

Figure 1.

Phenotypes of blebbed mouse embryos. (A) Frequency of RA in 224 embryos from double heterozygous Fras1bl/+;Spry1LacZ/+ parents. F, Fras1 null allele; S, Spry1 null allele; +, wild-type alleles. (B–G) Whole mounts of intact embryos and renal tracts from autopsies of E15 embryos. Note two kidneys in the Fras1+/+;Spry1+/+ embryo, their absence (asterisks) in the Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+ embryo, and their presence in the Fras1bl/bl;Spry1Lac/+ embryo. Skin hemorrhage is present in Fras1bl/bl genotypes. Scale bars = 1 mm.

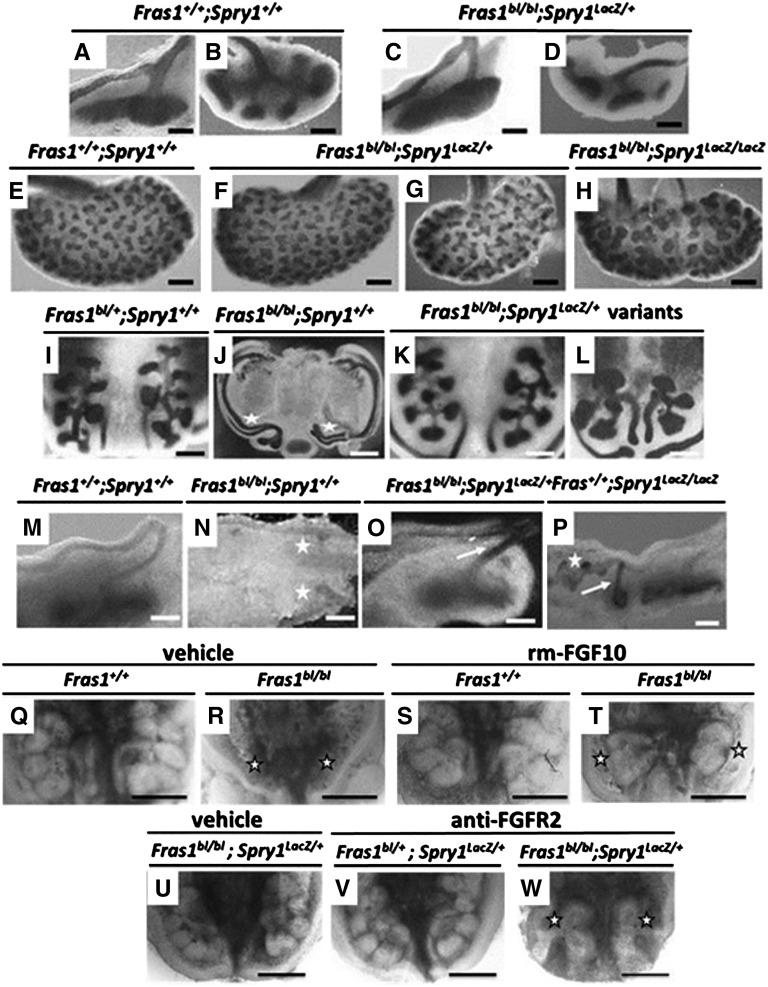

Ureteric trees were visualized with antibodies to paired box gene 2 (PAX2) or E-cadherin. At E11, rescued metanephroi resembled wild types, with the ureteric bud having penetrated the MM (Figure 2, A and C). One day later, wild-type and Fras1blbl;Spry1LacZ/+ metanephroi contained a ureteric tree (Figure 2, B and D), and further, extensive branching had taken place by E15 in both wild types and in rescued FS kidneys (Figure 2, E–G). There was, however, a modest but significant (P<0.001, Mann-Whitney test) reduction in branch tips in rescued (n=16) versus wild-type (n=10) E12 metanephroi; the respective median numbers (ranges) of branch tips were 8.5 (5–11) and 10 (10–12). A similar modest depletion of tips was measured at E15 in a comparison of rescued (n=18) with wild-type (n=10) organs; the respective medians (ranges) were 199 (146–235) and 240 (225–253). We explanted E11 nephrogenic fields, recording phenotypes after 24 hours. Fras1+/+ explants carrying wild-type Spry1 alleles or a single Spry1 null allele formed paired metanephroi, each containing a branched ureteric bud (Figure 2I). Ureteric trees failed to form in Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+ explants (Figure 2J). Introduction of a single Spry1LacZ allele rescued emergence and branching of ureteric buds (Figure 2K), although tips were sometimes distorted (Figure 2L). Fras1+/+;Spry1+/+ mesonephric ducts and ureteric buds expressed activated pERK (Figure 2M), whereas Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+ embryos exhibited attenuated pERK in mesonephric ducts and, when present, in ureteric bud stumps (Figure 2N). pERK was restored in the ureteric bud stalk and branches of rescued Fras1bl/bl embryos (Figure 2O), with multiple ectopic pERK-expressing buds noted in explants carrying two mutant Spry1 alleles (Figure 2P).

Figure 2.

Branching morphogenesis. (A–H) E11 (A and C), E12 (B and D), and E15 (E–H) whole mounts were PAX2 (A and C) or E-cadherin (B and D and E–H) immunostained. Note similar branching patterns in Fras1+/+;Spry1+/+ (A, B, E) and rescued Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ metanephroi (C, D, F, and G). Note the Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/LacZ duplex kidney (H). (I–L) Embryonic renal tracts were cultured for 24 hours. Wild-type branching pattern, visualized after E-cadherin immunostaining (black), is shown in I. Fras1bl/bl mutants with two wild-type Spry1 alleles had absent metanephroi (asterisks in J), although their nephric ducts were intact. In Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ explants, ureteric bud branching occurs (K and L), although sometimes branching is less than normal. (M–P) Whole-mount immunostaining for pERK in E11 renal tracts. Note expression in mesonephric duct, ureteric buds (arrows in O and P), and first ureteric bud branches in wild-type (M) and Spry1LacZ/+ rescued FS (O) tissues. Expression is minimal in Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+ renal tracts (ureteric bud stumps indicted by asterisks in N). Note that the presence of two Spry1LacZ/LacZ alleles caused ectopic buds that expressed pERK (P). Positive immunostaining appears black. (Q–T) Whole mounts of explanted E11 wild-type and Fras1bl/bl E11 nephrogenic fields (n=4 in each genotype) maintained for 2 days. Q and R were grown in vehicle alone; note bilateral RA (stars in R) in the mutant culture. S and T were grown with recombinant FGF10; note that two rudimentary kidney (stars in T) have formed in the mutant culture. (U–W) Whole mounts of explanted E11 nephrogenic fields maintained for 2 days in vehicle alone (U) or vehicle supplemented with FGFR2-blocking antibody (V and W) (n=3 in each group). Note that the Sprouty1-induced rescue of RA (U) was markedly reduced in the presence of blocking antibody (stars in W). For comparison, a Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ explant exposed to blocking antibody is shown in V. Scale bars = 100 μm in A and C and M–P; 200 μm in B, D, and I–W; and 250 μm in E–H.

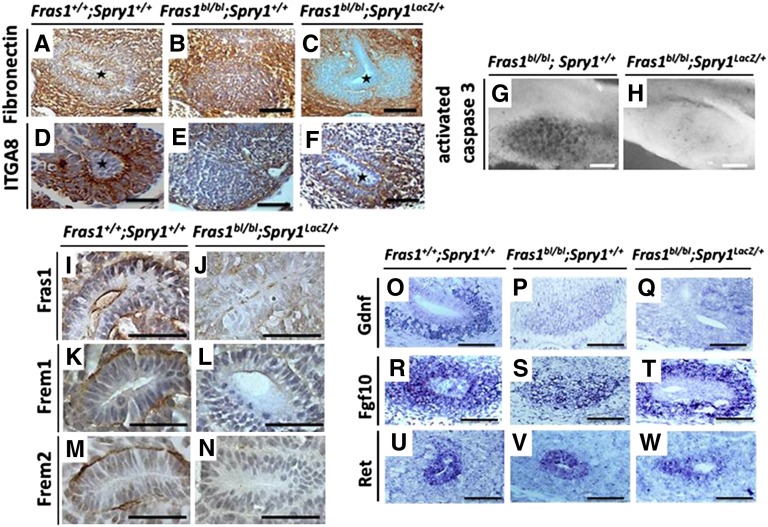

Wild-type E11 MMs expressed integrin-α8 but not fibronectin (Figure 3, A and D), whereas Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+ MMs showed an opposite, uninduced pattern21 (Figure 3, B and E). In contrast, MMs in Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ metanephroi (Figure 3, C and F) displayed the induced pattern of expression of these two proteins.21 FS rudiments rescued by a Spry1LacZ allele displayed a marked downregulation of apoptosis versus nonrescued rudiments (Figure 3, G and H). Whereas wild-type E11 metanephroi expressed FRAS1 and related proteins, FREM1 and FREM2, FRAS1 was absent and the other proteins downregulated in rescued kidney rudiments (Figure 3, I–N). This observation supports the existence of a reciprocally stabilized FRAS1/FREM1/FREM2 complex in kidneys, as previously demonstrated in skin.11–13

Figure 3.

Gene expression in E11 rudiments. (A–F) Immunohistochemistry for fibronectin and integrin-α8 (positive signals in brown). Molecularly induced MM (low fibronectin and high integrin-α8) in wild-type (A and D) and rescued FS (C and F) MMs. MM was uninduced (high fibronectin and low integrin-α8) in Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+ embryos (B and E). Note that fibronectin is also expressed in a fine layer around ureteric buds and in all genotypes is expressed in nonrenal mesenchyme around MMs themselves. (G and H) Immunohistochemistry for activated caspase-3 (black). Fulminant apoptosis in Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+ but minimal apoptosis in Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ rudiments. (I–N) Immunostaining (brown) for FRAS family proteins (FRAS1, FREM1 FREM2). All three were detected around the wild-type ureteric bud (I, K, and M), but all three were absent (FRAS1) or downregulated (FREM1 and FREM2) in the Spry1LacZ/+ rescued FS renal primordium (J, L, and N). (O–W) In situ hybridization (positive signal purple) for Gdnf (O–Q), Fgf10 (R–T), and Ret (U–W). Note that both nonrescued and rescued Fras1bl/bl rudiments have low Gdnf expression (P and Q) versus wild types (O). Fgf10 and Ret are expressed in all three genotypes. Scale bars = 50 μm in I–N and 100 μm in other frames.

E11 MMs of Fras1bl/bl mice have reduced Gdnf expression compared with wild types, although Ret expression is preserved in mesonephric ducts and ureteric bud stumps.21 We used in situ hybridization to visualize Gdnf and Ret expression (Figure 3, O–Q and U–W). Because ureteric bud outgrowth was restored in Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ embryos, we considered that their MMs might show a restored, normal level of Gdnf expression; however, this was not found to be the case (Figure 3Q). The observation are consistent with the idea that, by unknown means, FRAS1 is required for full Gdnf expression and that the Gdnf deficiency in Fras1 mutant MMs is not simply a nonspecific finding in an involuting rudiment. At first, this seems at variance with the severity of RA in the mutants because, for example, Gdnf haploinsufficiency does not per se cause severe renal malformations.24 Perhaps a lack of functional FRAS1 also perturbs effective presentation of GDNF to RET, and we observed a marked downregulation of pERK protein in nonrescued Fras1bl/bl renal epithelia. Furthermore, downregulated GDNF signaling may not be the only explanation for RA in blebbed mice, and we reported an upregulation of pSMAD1/5/8, a marker of antibranching signals, around Fras1bl/bl mesonephric ducts.21

Genetic evidence indicates that fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10), another molecule signaling through RTK/ERKs, can replace the need for GDNF/RET in ureteric bud initiation, especially when SPRY1 is absent.24,28 We detected Fgf10 transcripts in wild type and both Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+ and Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ MMs (Figure 3, R–T). Addition of FGF10 to explanted Fras1bl/bl (wild-type Spry1) nephrogenic fields resulted in a partial rescue of RA (Figure 2, Q–T). Moreover, addition of an FGFR2-blocking antibody prevented the full rescue of RA in explanted Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ renal tracts (Figure 2, U–W). Thus, local expression of FGFs may play a role in Spry1-induced rescue of RA in Gdnf-depleted Fras1bl/bl embryos.

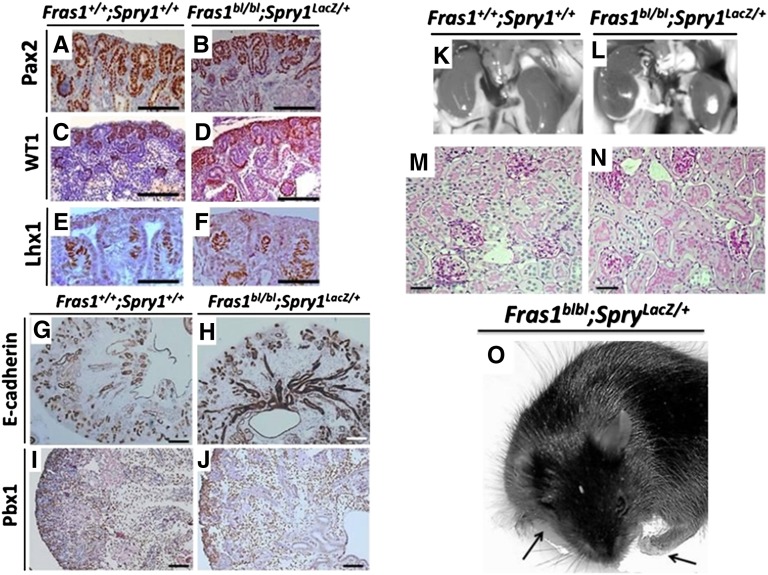

After the kidney rudiment has initiated, Fras1 transcripts and FRAS1 protein are expressed in the differentiating nephrons and collecting ducts.21 We undertook immunohistochemistry of E15 kidneys (Figure 4, A–J, and Supplemental Figure 1). In wild types, PAX2 was detected in ureteric bud branch tips, collecting ducts, and nephrogenic mesenchyme; Wilms tumor 1 transcription factor was detected in nephrogenic mesenchyme and nephron precursors; Lin-11, Is1-1, Mec-3 (LIM)-homeodomain transcription factor-1 was detected in pretubular aggregates; E-cadherin was expressed in ureteric trees and nascent nephrons; and pre–B cell leukemia homeobox 1 transcription factor was detected in mesenchyme and stroma. Similar patterns were found in rescued Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ kidneys. We allowed two litters from double heterozygous parents to be born, genotyped, and aged to 6–8 weeks. As expected, because bilateral RA is incompatible with survival, no mice were Fras1bl/bl;Spry1+/+. We found two Fras1bl/bl; Spry1LacZ/+ adult mice, and although they displayed syndactyly and cryptophthalmos (Figure 4O) (typical FS external dysmorphologic features), they appeared otherwise healthy. Each had two kidneys containing glomeruli and proximal tubules (Figure 4, K–N). From the current experiments it cannot be concluded that FRAS1 is expendable for the later stages of nephrogenesis. As well as being expressed in the initiating metanephros, developing nephrons (GenitoUrinary Development Molecular Anatomy Project; http://www.gudmap.org/) express Spry1, so we cannot exclude the possibility that Spry1 haploinsufficiency also confers beneficial effects on nephrogenesis in Fras1bl/bl kidneys. Indeed, we reported that targeted genetic downregulation of FRAS1 in developing podocytes causes mild glomerulosclerosis.29

Figure 4.

Progression of kidney development and maturation. (A–J) E15 kidney sections counterstained (blue) with hematoxylin. Note that wild-type and Spry1-rescued Fras1bl/bl kidneys showed similar immunohistochemical patterns (brown) for PAX2 (A and B) in ureteric bud branch tips and adjacent MM; Wilms tumor 1 (C and D) in MM, nephron vesicles, and S-shaped bodies; LIM-homeodomain transcription factor-1 (E and F) in nephron precursors; E-cadherin (G and H) in collecting ducts and ureteric bud branch tips; and pre–B cell leukemia homeobox 1 (I and J) in cortical and deeper mesenchyme. (K–N) Findings on autopsies from wild-type (K) and Spry1-rescued FS (L) mice with respective histologic features showing glomeruli and proximal tubules in sections stained with hematoxylin and periodic-acid Schiff (pink brush borders). (O) Adult Fras1bl/bl;Spry1LacZ/+ mice appeared overtly healthy, although they were not rescued from the characteristic eye (cryptophthalmos) and digit (syndactyly) dysmorphologic features (arrows) that characterize blebbed mice and humans with FS. Scale bars = 25 μm in G–J; 50 μm in E, F, M, and N; and 100 μm in A–D.

Introducing a single null Spry1 allele in Fras mutant mice permits near-normal kidney formation with survival to adulthood. A similar rescue of RA occurs in Gremlin null mice by introducing a mutant Bmp4 allele.30 Nevertheless, humans with GREM1 mutations and RA have yet to be described,31 whereas FRAS1 mutations cause FS and RA. RTK inhibitors can decrease cancer32 and kidney cyst growth.33 Testing time-limited gestational administration of drugs upregulating RTK pathway activity in Fras1bl/bl mice may ameliorate RA.

Concise Methods

Experiments were undertaken in accordance with the United Kingdom Home Office Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. bl mice were originally obtained from MRC Mammalian Genetics Unit (Harwell, United Kingdom). Fras1bl had been propagated in a C57BL6J background for more than 10 generations by crossing heterozygous with wild-type mice. For some experiments, we bred the Fras1bl allele into mice carrying the Spry1LacZ allele, itself maintained on a C57BL6J background for more than four generations. Genotypes were determined by PCR (details available on request). Nephrogenic fields (i.e., paired mesonephroi, mesonephric ducts, and adjacent MMs) were dissected in ice-cold PBS, and limbs were used for genotyping. Tissue samples were placed on cellulose filters and fed with DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% recombinant human insulin, human transferrin, and sodium selenite (ITS, Sigma) and antifungal and antibiotic mixture (Sigma). They were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2/air atmosphere for 24 hours. Explants were photographed through a dissecting microscope and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for whole-mount immunostaining with E-cadherin antibody to visualize branching ureter.

Embryos were collected in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histology and whole-mount analyses. Embryos used to derive tissues for in vitro culture were collected into ice-cold L15 medium (Invitrogen). In vitro culture of E11 kidney explants for 48 hours was performed as previously described.21 In some cultures, mouse recombinant FGF10 (R&D Systems, 6224-FG/CF) was applied at the concentration of at least 500 ng/ml in DMEM/F12 medium (Invitrogen), whereas in others, control media were supplemented with monoclonal antibody against FGFR2 at concentration of 5 μg/ml to achieve neutralizing effect according to manufacturer instructions (R&D Systems, clone 98707); the antibody is reported to preferentially block FGFR2 IIIb isoform, which binds FGFs 1, 3, 7, 10, and 22 with preference to FGF7 and FGF10. Dehydrated embryos were embedded in paraffin or stored at −20°C in methanol for immunostaining. Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti–cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling), rabbit antifibronectin (DAKO), rabbit anti-FRAS1,21 rabbit anti-FREM1 (Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-FREM2 (a gift from I. Smyth, Monash University, Australia), rabbit anti–integrin-α8 (a gift from U. Muller, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), mouse anti–E-cadherin (Pharmingen), rabbit anti-PAX2 (Zymed), rabbit anti–LIM-homeodomain transcription factor-1 (Chemicon), rabbit anti–pre–B cell leukemia homeobox 1 (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-pERK1/2 (Cell Signaling), and rabbit anti–Wilms tumor 1 (Santa Cruz). Immunohistochemistry on paraffin sections was performed as described elsewhere.21 Secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated and signals generated with DAB chromogen (DAKO).

Whole-mount immunostaining was performed as described.21 Briefly, specimens were rehydrated into PBS and endogenous peroxidase inactivated with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Specimens were incubated with individual primary antibodies and then washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody. Colorimetric reaction was with DAB (DAKO). In situ hybridization was performed on paraffin sections as described elsewhere.21 Briefly, sections were digested with proteinase K (10 mg/ml), hybridized overnight at 65°C in a humidified chamber with probes labeled with digoxigenin and detected with sheep antidigoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. Color signals were generated with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyphosphate/nitro-blue tetrazolium chloride. In situ hybridization probes used were as follows: Gdnf (a gift from A.L. Zimmer, University of Bonn), Ret (a gift from F. Costantini, Columbia University, New York, NY), and Fgf10 (from M.A. Basson). Apoptotic cells were detected with anti–cleaved caspase 3 antibody on dissected kidney using whole-mount immunostaining.

For each histologic/gene expression analysis, between two and five wild-type and FS rescued and nonrescued embryos were examined at each stage, allowing the reporting of reproducible data. The two-tailed Fisher exact test was used to compare the distribution of RA between different genotypes. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare numbers of ureteric bud branch tips between genotypes.

Disclosure

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank to F. Costantini and A.L. Zimmer for in situ hybridization probes used in this study.

The work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grants 073624 and 085077 to A.S.W., J.E.P., and P.J.S.), Kidney Research UK (grant RP35/2008 to A.S.W., J.E.P., and P.J.S.), the Manchester National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre (to A.S.W.), Kids Kidney Research (to A.S.W., J.E.P., and P.J.S), and Kidneys for Life (to A.S.W.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2012020146/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wiesel A, Queisser-Luft A, Clementi M, Bianca S, Stoll C, EUROSCAN Study Group : Prenatal detection of congenital renal malformations by fetal ultrasonographic examination: an analysis of 709,030 births in 12 European countries. Eur J Med Genet 48: 131–144, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duke V, Quinton R, Gordon I, Bouloux PM, Woolf AS: Proteinuria, hypertension and chronic renal failure in X-linked Kallmann’s syndrome, a defined genetic cause of solitary functioning kidney. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 1998–2003, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanna-Cherchi S, Ravani P, Corbani V, Parodi S, Haupt R, Piaggio G, Innocenti ML, Somenzi D, Trivelli A, Caridi G, Izzi C, Scolari F, Mattioli G, Allegri L, Ghiggeri GM: Renal outcome in patients with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Kidney Int 76: 528–533, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harewood L, Liu M, Keeling J, Howatson A, Whiteford M, Branney P, Evans M, Fantes J, Fitzpatrick DR: Bilateral renal agenesis/hypoplasia/dysplasia (BRAHD): postmortem analysis of 45 cases with breakpoint mapping of two de novo translocations. PLoS ONE 5: e12375, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolf AS, Hillman KA: Unilateral renal agenesis and the congenital solitary functioning kidney: developmental, genetic and clinical perspectives. BJU Int 99: 17–21, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slavotinek AM, Tifft CJ: Fraser syndrome and cryptophthalmos: review of the diagnostic criteria and evidence for phenotypic modules in complex malformation syndromes. J Med Genet 39: 623–633, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Haelst MM, Scambler PJ, Hennekam RC, Fraser Syndrome Collaboration Group : Fraser syndrome: A clinical study of 59 cases and evaluation of diagnostic criteria. Am J Med Genet A 143A: 3194–3203, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGregor L, Makela V, Darling SM, Vrontou S, Chalepakis G, Roberts C, Smart N, Rutland P, Prescott N, Hopkins J, Bentley E, Shaw A, Roberts E, Mueller R, Jadeja S, Philip N, Nelson J, Francannet C, Perez-Aytes A, Megarbane A, Kerr B, Wainwright B, Woolf AS, Winter RM, Scambler PJ: Fraser syndrome and mouse blebbed phenotype caused by mutations in FRAS1/Fras1 encoding a putative extracellular matrix protein. Nat Genet 34: 203–208, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Short K, Wiradjaja F, Smyth I: Let’s stick together: the role of the Fras1 and Frem proteins in epidermal adhesion. IUBMB Life 59: 427–435, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smyth I, Scambler P: The genetics of Fraser syndrome and the blebs mouse mutants. Hum Mol Genet 14 Spec No. 2:R269–274, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiyozumi D, Osada A, Sugimoto N, Weber CN, Ono Y, Imai T, Okada A, Sekiguchi K: Identification of a novel cell-adhesive protein spatiotemporally expressed in the basement membrane of mouse developing hair follicle. Exp Cell Res 306: 9–23, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiyozumi D, Sugimoto N, Sekiguchi K: Breakdown of the reciprocal stabilization of QBRICK/Frem1, Fras1, and Frem2 at the basement membrane provokes Fraser syndrome-like defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 11981–11986, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavlakis E, Chiotaki R, Chalepakis G: The role of Fras1/Frem proteins in the structure and function of basement membrane. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 43: 487–495, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jadeja S, Smyth I, Pitera JE, Taylor MS, van Haelst M, Bentley E, McGregor L, Hopkins J, Chalepakis G, Philip N, Perez Aytes A, Watt FM, Darling SM, Jackson I, Woolf AS, Scambler PJ: Identification of a new gene mutated in Fraser syndrome and mouse myelencephalic blebs. Nat Genet 37: 520–525, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vrontou S, Petrou P, Meyer BI, Galanopoulos VK, Imai K, Yanagi M, Chowdhury K, Scambler PJ, Chalepakis G: Fras1 deficiency results in cryptophthalmos, renal agenesis and blebbed phenotype in mice. Nat Genet 34: 209–214, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saisawat P, Tasic V, Vega-Warner V, Kehinde EO, Günther B, Airik R, Innis JW, Hoskins BE, Hoefele J, Otto EA, Hildebrandt F: Identification of two novel CAKUT-causing genes by massively parallel exon resequencing of candidate genes in patients with unilateral renal agenesis. Kidney Int 81: 196–200, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vissers LE, Cox TC, Maga AM, Short KM, Wiradjaja F, Janssen IM, Jehee F, Bertola D, Liu J, Yagnik G, Sekiguchi K, Kiyozumi D, van Bokhoven H, Marcelis C, Cunningham ML, Anderson PJ, Boyadjiev SA, Passos-Bueno MR, Veltman JA, Smyth I, Buckley MF, Roscioli T: Heterozygous mutations of FREM1 are associated with an increased risk of isolated metopic craniosynostosis in humans and mice. PLoS Genet 7: e1002278, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grobstein C: Inductive epitheliomesenchymal interaction in cultured organ rudiments of the mouse. Science 118: 52–55, 1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woolf AS, Pitera JE: Embryology. In Pediatric Nephrology, 6th Ed., edited by Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, Yoshikawa N, New York, NY, Springer, 2009, pp 3–30 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little M, Georgas K, Pennisi D, Wilkinson L: Kidney development: Two tales of tubulogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol 90: 193–229, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitera JE, Scambler PJ, Woolf AS: Fras1, a basement membrane-associated protein mutated in Fraser syndrome, mediates both the initiation of the mammalian kidney and the integrity of renal glomeruli. Hum Mol Genet 17: 3953–3964, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Towers PR, Woolf AS, Hardman P: Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor stimulates ureteric bud outgrowth and enhances survival of ureteric bud cells in vitro. Exp Nephrol 6: 337–351, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chi X, Michos O, Shakya R, Riccio P, Enomoto H, Licht JD, Asai N, Takahashi M, Ohgami N, Kato M, Mendelsohn C, Costantini F: Ret-dependent cell rearrangements in the Wolffian duct epithelium initiate ureteric bud morphogenesis. Dev Cell 17: 199–209, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costantini F: GDNF/Ret signaling and renal branching morphogenesis: From mesenchymal signals to epithelial cell behaviors. Organogenesis 6: 252–262, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M, Galuppo P, Just S, Rottbauer W, Frantz S, Castoldi M, Soutschek J, Koteliansky V, Rosenwald A, Basson MA, Licht JD, Pena JT, Rouhanifard SH, Muckenthaler MU, Tuschl T, Martin GR, Bauersachs J, Engelhardt S: MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature 456: 980–984, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basson MA, Akbulut S, Watson-Johnson J, Simon R, Carroll TJ, Shakya R, Gross I, Martin GR, Lufkin T, McMahon AP, Wilson PD, Costantini FD, Mason IJ, Licht JD: Sprouty1 is a critical regulator of GDNF/RET-mediated kidney induction. Dev Cell 8: 229–239, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basson MA, Watson-Johnson J, Shakya R, Akbulut S, Hyink D, Costantini FD, Wilson PD, Mason IJ, Licht JD: Branching morphogenesis of the ureteric epithelium during kidney development is coordinated by the opposing functions of GDNF and Sprouty1. Dev Biol 299: 466–477, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michos O, Cebrian C, Hyink D, Grieshammer U, Williams L, D’Agati V, Licht JD, Martin GR, Costantini F: Kidney development in the absence of Gdnf and Spry1 requires Fgf10. PLoS Genet 6: e1000809, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitera JE, Turmaine M, Woolf AS, Scambler PJ: Generation of mice with a conditional null Fraser syndrome 1 (Fras1) allele [published online ahead of print June 22, 2012]. Genesis doi: 10.1002/dvg.22045 10.1002/dvg.22045 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Michos O, Gonçalves A, Lopez-Rios J, Tiecke E, Naillat F, Beier K, Galli A, Vainio S, Zeller R: Reduction of BMP4 activity by gremlin 1 enables ureteric bud outgrowth and GDNF/WNT11 feedback signalling during kidney branching morphogenesis. Development 134: 2397–2405, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. GREMLIN 1 homolog, cystine knot superfamily; GREM1. June 14, 2012. Available at: http://omim.org/entry/603054 Accessed June 12, 2012

- 32.Carracedo A, Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Rojo F, Salmena L, Alimonti A, Egia A, Sasaki AT, Thomas G, Kozma SC, Papa A, Nardella C, Cantley LC, Baselga J, Pandolfi PP: Inhibition of mTORC1 leads to MAPK pathway activation through a PI3K-dependent feedback loop in human cancer. J Clin Invest 118: 3065–3074, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torres VE, Sweeney WE, Jr, Wang X, Qian Q, Harris PC, Frost P, Avner ED: EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition attenuates the development of PKD in Han:SPRD rats. Kidney Int 64: 1573–1579, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.