Abstract

Aim:

To determine the effect of preoperative administration of paracetamol (PARA), ibuprofen (IBUP), or aceclofenac (ACEC) on the success of maxillary infiltration anesthesia in patients with irreversible pulpitis in a double-blinded randomized controlled trial.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and twenty patients with irreversible pulpitis of a maxillary first molar participated. Patients indicated their pain scores on a Heft Parker visual analog scale, after which they were randomly divided into four groups (n = 30). The subjects received identical capsules containing 1000 mg PARA, 800 mg IBUP, 100 mg ACEC or cellulose powder (placebo, PLAC), 1 h before administration of maxillary infiltration anesthesia with 2% lidocaine containing 1:200,000 epinephrine. Access cavities were then prepared and success of anesthesia was defined as the absence of pain during access preparation and root canal instrumentation. The data were analyzed using chi-squared tests.

Results:

The success rates in descending order were 93.3% (IBUP), 90% (ACEC), 73.3% (PARA), and 26.5 % (PLAC). A significant (P < 0.001) difference was found between the drug groups and the PLAC group.

Conclusions:

Pre-operative administration of PARA, IBUP, and ACEC significantly improved the efficacy of maxillary infiltration anesthesia in patients with irreversible pulpitis.

Keywords: Aceclofenac, ibuprofen, irreversible pulpitis, local anesthesia, maxillary infiltration anesthesia, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, Paracetamol

INTRODUCTION

Achieving profound anesthesia is one of the pre-requisites of commencing endodontic treatment. Although local anesthetics are highly effective in producing anesthesia in normal tissues, they commonly fail in patients with inflamed tissues.[1] For instance, the inferior alveolar nerve block is associated with a failure rate of 15% in patients with normal tissue[2] and 44–81% with irreversible pulpitis[3] and 30% failure in maxillary infiltration in teeth with irreversible pulpitis.[2] Various reasons cited are decreased tissue pH[4] and activation of nociceptors, including tetrodotoxin and capsaicin-sensitive transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1).[5]

Prostaglandin-induced sensitization of peripheral nociceptors[6] has been commonly implicated in anesthesia failure. Prostaglandins (PGs) up-regulate a variety of mechanisms that might decrease the efficacy of local anesthetics. It alters the kinetics of activity of the voltage-gated sodium channels, resulting in increased depolarization, activation of EG protein-coupled receptors, namely P2 or EP3 receptors, which are expressed on trigeminal sensory neurons.[7]

The rationale for the pharmacological management of pain using NSAIDS is focused on the reduction of chemical inflammatory mediators (PGs) involved in pain. There are numerous published reports[8,9] on increasing the efficacy of anesthetics in the mandible but the clinical approaches to achieve successful anesthesia in maxillary teeth with irreversible pulpitis have not been explored sufficiently. The efficacy of anesthesia close to the site of inflammation can be evaluated better in infiltration injection techniques rather than in nerve blocks. The causes for anesthesia failure in mandibular teeth include accessory innervations of teeth with mylohyoid nerve,[10] cross innervations,[11] and central core theory in inferior alveolar nerve.[12] These variables are absent in the maxillary teeth and hence they were selected for the present study.

Therefore, the purpose of this prospective, randomized, double-blinded study was to compare the efficacy of oral pre-medication of paracetamol (PARA), ibuprofen (IBUP), aceclofenac (ACEC), and a placebo (PLAC) medication on anesthetic efficacy of maxillary infiltration of lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine in patients with irreversible pulpitis. The null hypothesis tested was that there is no significant difference among the four groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One hundred twenty adult patients, who reported with pain, within the age group of 20–40 years were selected for the study. The eligibility criteria to participate in the clinical trial were as follows: healthy patients (ASA I or ASA II) with a vital maxillary first molar experiencing intermittent or spontaneous pain which had a prolonged response to cold testing with Endo-Ice (1, 1, 1, 2 tetrafluoroethane, Hygenic Corp., Akron, OH) and an electric pulp tester (Kerr, Analytic Technology Corp., Redmond, WA). This was done to confirm the diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis. Also, the absence of periapical radiolucency on radiographs, except for a widened periodontal ligament (not more than 0.75–1 mm), and patients with the ability to understand the use of pain scales were selected. Subjects who had pulpitis in teeth other than the first maxillary molar in the same quadrant were excluded from the study. Other reasons for exclusion were those with known allergy or contraindications to analgesics: patients with a history of active peptic ulcer within the preceding 12 months, bleeding problems or anticoagulant use within the last month, opioid, nonopioid analgesics, steroids, antidepressants, or sedatives use within 12–24 h before administration of the study drugs. The excluded patients were appropriately managed based on their existing clinical conditions.

Ethical approval was sought from the Institutional Review Board and Ethical committee of the University. Informed written consent was obtained from each subject. Randomization of patients was done by simple random sampling with a linear congruential generator. Randomized allocation of the patients was done by a trained dental hygienist who was blinded to the treatment procedures.

Every patient was asked to rate his/her pain on a Heft Parker visual analog scale (VAS) with 170-mm line marked with various terms describing the levels of pain (Heft and Parker 1984). The millimeter marks were removed from the scale, and the scale was divided into four categories: no pain corresponded to 0 mm; faint, weak or mild pain corresponded to 1–54 mm; moderate to severe pain corresponded to 55–114 mm; and strong, intense, maximum possible pain corresponded to more than 114 mm.[13] Patients were instructed to place a mark on the line to indicate the pain; this mark was then measured with the scale and the score was recorded.

A university hospital pharmacist divided 120 empty capsules of same color and size into 4 bottles: paracetomol (PARA), ibuprofen (IBUP), aceclofenac (ACEC), and placebo (PLAC) groups. PARA capsules were filled with 1000 mg of paracetamol, IBUP capsules with 800 mg of ibuprofen, ACEC capsules with 100 mg aceclofenac, and PLAC capsules with starch. The bottles were masked with an opaque label and were randomly assigned a three-digit alphanumeric value. A trained dental hygienist randomly divided all the patients into four groups of 30 patients each and gave one capsule 1 h before the procedure.

Topical anesthetic gel 2% lidocaine (xylocaine jelly, AstraZeneca, India) was passively placed at the infiltration site for 60 s using a cotton-tip applicator. A single operator gave all the injections of 1.8 ml of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:200,000 (xylocaine 2% with epi 1:200,000) using standard dental aspirating syringe fitted with a 27-gauge, 1.5-inch needle and this operator had no involvement with testing the outcome.

After 5 min, the tooth in question was tested again with cold spray. If the patient felt pain or sensitivity, the test was recorded as a failure and eliminated from the study. However, no subjects were eliminated in this criterion. A rubber dam was placed and a standard endodontic access cavity was begun with a bur under water spray coolant and pulp extripation done. In the case of pain during the treatment, the procedure was stopped, and patients were asked to rate the pain on Heft Parker VAS. The success of the technique was defined as the ability to access and extripate pulp without pain (VAS = 0 mm) or mild discomfort/sensitivity (VAS ≤ 54 mm). If the score was ≤54 mm, the outcome was recorded as failure and supplementary anesthesia was administered and the procedure was completed. The post injection VAS scores were recorded at the end of the procedure.

The findings were recorded on a Microsoft Excel sheet (Microsoft Office Excel 2003; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) for statistical evaluation by using the SPSS software. Age and initial and post-injection pains of the subjects were summarized by using means and standard deviations. Multiple comparison analysis of variance and post hoc tests were used to determine significant differences. Anesthetic success of the PARA, IBUP, ACEC, and PLAC groups was dichotomous in nature and was analyzed by using chi-square tests.

RESULTS

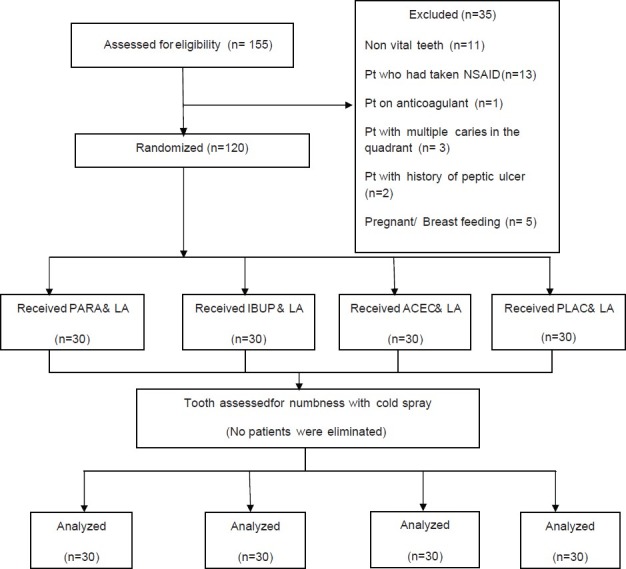

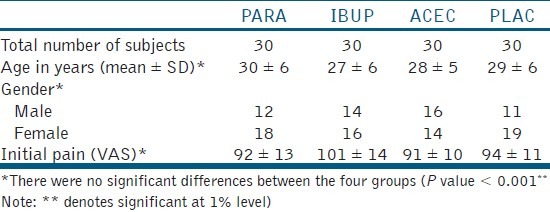

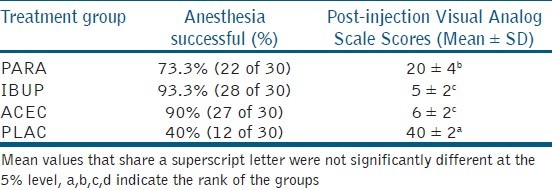

The Structure of RCT and the number of enrolled in the intention to treat is given in [Figure 1]. The age, gender, and mean initial VAS scores were tabulated [Table 1]. There were no significant differences (P < 0.001) between the four groups. The post-injection VAS scores are given in Table 2. There was significant difference between the PLAC and the three drug groups. IBUP and ACEC groups demonstrated significantly lower scores than the PARA group. However, there was no significant difference between IBUP and ACEC groups (P < 0.001). The number and percentage of patients with successful maxillary infiltration anesthesia by the test, and control groups are presented in Table 2. The percentage of successful anesthesia was as following: 40% in the control PLAC group, whilst premedication with PARA, IBUP, and ACEC resulted in 73.3%, 93.3%, and 90%, respectively. The percentage of successful anesthesia was significantly higher in all the drug groups when compared with the PLAC group (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of RCT

Table 1.

comparison of age, gender, and initial heft parker visual analogue scale scores among the four groups

Table 2.

Comparison of percentage of inferior alveolar treatment group nerve block among the four groups

DISCUSSION

In irreversible pulpitis, breakdown of damaged cell membranes and release of arachidonic acid (AA) occurs. This AA is acted on by cycloxygenase (COX) enzyme and gets converted into 20-carbon chain molecules called eicosanoids. These are converted by cell-specific isomerases and synthases to produce five biologically active PGs: PGD2, PGE2, PGF2a, prostacyclin (PGI2), and thromboxane A2 (TxA2). These PGs sensitize nerve endings to bradykinins and histamines and cause the allodynia and hyperalgesia associated with inflammation.[14]

The success rates of local anesthesia have been found to be worse in patients with inflamed pulpal tissues.[15] Numerous reports[16,17] suggest that activation of nociceptors by inflammatory mediators such as PGs are a major cause of increased failure of anesthesia. Peripheral terminals of nociceptors express certain protein receptors which can detect chemical and physical stimuli. Inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins produce their effects by binding to these various protein receptors resulting in activation of various ion channels expressed on peripheral terminals. These mediators reduce the threshold for activation of nociceptor neurons to a point that a minor stimulus might fire the neurons.

The primary action of local anesthetics in producing a conduction block is to decrease the permeability of voltage-gated sodium channels to sodium ions. There are at least nine different subtypes of sodium channels. Nociceptors express a tetrodotoxin-resistant (TTX-R) class of voltage-gated sodium channels that are relatively resistant to local anesthetics and are sensitized by prostaglandins. These TTX-R channels are of two specific isoforms Nav1.8 and Nav1.9 which play a key role in the generation and maintenance of inflammatory pain. Prostaglandins not only alter the kinetics of the channels’ activity, resulting in increased depolarization, but the actual TTX- R channels themselves are expressed at higher levels.[18] In a recent study, Wells et al.[19] using immunoreactivity found significantly increased levels of the TTX-R channels of Nav1.9 isoform in painful, inflamed teeth compared with asymptomatic dental pulps. Therefore, it can be concluded that by reducing the amount of prostaglandins, TTX-R channels become less active thereby increasing the anesthetic success.

Acetaminophen, aceclofenac, and ibuprofen are relatively safe, fast-acting analgesics that also control inflammation. Paracetamol has been used clinically for over a half of a century and remains the most popular analgesic/antipyretic used in children with its proven safety and efficacy.[20] The efficacy of ibuprofen (a propionic acid derivative) in postoperative dental pain is also well established. Aceclofenac (phenylacetic acid derivative) has anti-inflammatory properties similar to those of diclofenac and of indomethacin. In clinical studies, it has been shown to treat dental pain effectively.[21]

Nielsen et al.[22] showed that 800 mg ibuprofen was superior to 400 mg in a study of laser-induced pain. Skoglund et al.[23] compared 1,000 mg and 2,000 mg acetaminophen and reported total analgesia with 1,000 mg. Hence, 1,000 mg of acetaminophen, 800 mg of ibuprofen, and 100 mg of aceclofenac were chosen for this study. Premedication was given 1 h before the procedure to allow NSAIDs to achieve satisfactory plasma concentration.

The VAS is to be methodologically sound, conceptually simple, easy to administer, and unobtrusivse to the respondent. A combined metric scale (Heft-Parker) for pain measurement that provides the subject with multiple cues might improve communication and concordance between scales for individual pain determination.[13] Similar methodology was followed by other researchers[13,15]

The results of the study show that the increase in anesthetic effect of lidocaine was statistically significant in all the three drug groups compared to the placebo group. Similar results were found by Ianiro et al.[9]

The mechanism of action of most NSAIDs results by acetylating the cyclooxygenase enzyme, which in turn inhibits the synthesis of prostaglandins. Thus, NSAIDs nonspecifically prevent both the COX-1 and COX-2 isoenzymes from forming arachidonic acid metabolites. Because there is induction of COX-2 at sites of inflammation, it is believed that the therapeutic properties of NSAIDs account primarily for the inhibition of COX-2.[24]

While ibuprofen and aceclofenac are both NSAIDs, they have different chemical structures. Ibubrufen is a non-selective COX inhibitor and aceclofenac is a selective COX-2 inhibitor. Ibuprofen also inhibits the migration and other functions of leucocytes, while aceclofenac reduces intracellular concentrations of free arachidonate in leucocytes. Although the action of acetaminophen is unknown, it has been suggested that it interferes with inflammation by diminishing the synthesis of prostaglandins (possibly PGF2). An alternative explanation is that a PGHS variant (COX-3) exists in the central nervous system (CNS), and that this variant is exquisitely sensitive to PARA.[25] This premise also needs further inspection.

The IBUP and ACEC group demonstrated better analgesic effect than the PARA group. This could be because PARA has a weak analgesic/anti-inflammatory effect and a strong antipyretic effect. Also, the suppression of PGs at the inflammatory site appears to be at a minor level and the predominant mechanisms largely responsible for PARA's analgesic activity are located in the CNS.[20] In the present study, there was no significant difference between the IBUP and ACEC groups as both the drugs inhibit COX-2 enzyme which plays a major role in inflammation. However, further research is needed in this direction. A further clinical trial with a larger sample size would strengthen the results of the present study.

CONCLUSION

Oral pre-medication with 800 mg IBUP, 100 mg ACEC, and 1000 mg PARA resulted in significantly higher percentage of successful maxillary infiltration anesthesia in patients with irreversible pulpitis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meechan JG. Supplementary routes to local anaesthesia. Int Endod J. 2002;35:885–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingle JI, Bakland LK. Endodontics. 5th ed. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker; 2002. Preparation for Endodontic Treatment; p. 385. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthews R, Drum M, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M. Articaine for supplemental buccal mandibular infiltration anaesthesia in patients with irreversible pulpitis when the inferior alveolar nerve block fails. J Endod. 2009;35:343–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hargreaves KM, Keiser K. Local anesthetic failure in endodontics: Mechanisms and management. Endod Top. 2002;1:26–39. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhary P, Martenson ME, Baumann TK. Vanilloid receptor expression and capsaicin excitation of rat dental primary afferent neurons. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1518–23. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800060801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henry MA, Hargreaves KM. Peripheral mechanisms of odontogenic pain. Dent Clin North Am. 2007;51:19–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vane JR, Botting RM. Mechanism of action of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1998;104(3A):2S–8S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00203-9. 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modaresi J, Dianat O, Mozayeni MA. The efficacy comparison of ibuprofen, acetaminophen-codeine, and placebo premedication therapy on the depth of anaesthesia during treatment of inflamed teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ianiro SR, Jeansonne BG, McNeal SF, Eleazer PD. The effect of preoperative acetaminophen or a combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on the success of inferior alveolar nerve block for teeth with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2007;33:11–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frommer J, Mele FA, Monroe CW. The possible role of the mylohyoid nerve in mandibular posterior tooth sensation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1972;85:113–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1972.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yonchak T, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers WJ. Anesthetic efficacy of unilateral and bilateral inferior alveolar nerve blocks to determine cross innervation in anterior teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:132–5. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.115720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strichartz G. Molecular mechanisms of nerve block by local anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 1976;45:421–41. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197610000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claffey E, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M, Weaver J. Anaesthetic efficacy of articaine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks in patients with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2004;30:568–71. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000125317.21892.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dray A. Inflammatory mediators of pain. Br J Anaesth. 1995;75:125–31. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggarwal V, Jain A, Debipada K. Anesthetic efficacy of supplemental buccal and lingual infiltrations of articaine and lidocaine following an inferior alveolar nerve block in patients with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2009;35:925–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodis HE, Poon A, Hargreaves KM. Tissue pH and temperature regulate pulpal nociceptors. J Dent Res. 2006;85:1046–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910608501114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renton T, Yiangou Y, Baecker PA, Ford AP, Anand P. Capsaicin receptor VR1 and ATP purinoceptor P2X3 in painful and nonpainful human tooth pulp. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17:245–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tominaga M, Caterina MJ. Thermosensation and pain. J Neurobiol. 2004;61:3–12. doi: 10.1002/neu.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells JE, Bingham V, Rowland KC, Hatton J. Expression of Nav1.9 channels in human dental pulp and trigeminal ganglion. J Endod. 2007;33:1172–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith HS. Potential analgesic mechanism of acetaminophen. Pain Physician. 2009;12:269–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Presser Lima P, Fontanella V. Analgesic efficacy of aceclofenac after surgical extraction of impacted lower third molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:518–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen J, Bjerring P, Arendt L, Petterson K. A double-blind, placebo controlled, cross-over comparison of the analgesic effect of ibuprofen 400 mg and 800 mg on laser-induced pain. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:711–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skoglund L, Skjelbred P, Fyllingen G. Analgesic efficacy of acetaminophen 1000 mg, acetaminophen 2000 mg, and the combination of acetaminophen 1000 mg and codeine phosphate 60 mg versus placebo in acute postoperative pain. Pharmacotherapy. 1991;11:364–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehrich EW, Dallob A, De Lepeleire I, Van Hecken A, Riendeau D, Yuan W, et al. Characterization of rofecoxib as a cyclooxygenase- 2 isoform inhibitor and demonstration of analgesia in the dental pain model. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;65:336–47. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandrasekharan NV, Dai H, Roos KL, Evanson NK, Tomsik J, Elton TS, et al. COX-3, a cyclooxygenase- 1 variant inhibited by acetaminophen and other analgesic / antipyretic drugs: Cloning, structure, and expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13926–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162468699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]