Abstract

Introduction:

“SealBio”, an innovative, non-surgical endodontic treatment protocol, based on “regenerative concept” has been developed to manage pulp and periapically involved teeth.

Materials and Methods:

Subsequent to Institute's ethical clearance, 18 patients presenting with signs and symptoms of pulp and periapical disease were included in the study. (11/M, 7/F; Mean age - 44.7 years; range 15-76 years). The protocol included a modified cleaning and shaping technique involving apical clearing and foramen widening, combined with inducing bleeding and clot formation in the apical region. Calcium-sulphate based cement was condensed with hand pluggers into the canal orifices. An appropriate permanent restoration was given. The patients were followed-up clinically and radiographically at regular interval of 6 months. Six teeth in 3 patients were also evaluated pre and post treatment CBCT at 6-months.

Results:

The novel treatment protocol was found to be favourable in resolving periapical infection, both clinically and radiographically.

Conclusions:

This innovative endodontic treatment protocol highlights and reiterates the importance of cleaning and shaping and puts forth the possible role of stem cells and growth factors in healing after non-surgical endodontic therapy.

Keywords: CBCT, non-obturation Endodontic treatment, periapical healing, regenerative endodontics, sealBio

INTRODUCTION

One of the essential requisites for successful outcome of endodontic treatment is believed to be achieving sealing of root canal system at both; apical and coronal end of a disinfected root canal. Even with conventional guttapercha obturation, the ultimate aim is to achieve a cemental/fibrous barrier at the root apex.[1] Therefore, achieving a biological seal, “SealBio” should be preferable over an artificial barrier of sealer and guttapercha cones at the apical end of root canal system.

With the success achieved with “revascularization” in healing of periapical lesions and hard tissue deposition at apical and lateral walls of the root canals (maturogenesis) in immature teeth,[2–4] the processes involved in the healing mechanism are now better understood. Role of various stem cells, growth factors, Hertwig's epithelial root sheath (HERS) and their interactions in regeneration of tissues have been documented.[5]

Exploiting this mechanism of stimulating healing and regeneration of tissues and combining it with thorough disinfection of root canal system, a novel treatment approach was conceived to manage non-vital mature teeth with periapical pathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Institutional ethical clearance was obtained. Eighteen cases of pulp and periapical infection, irrespective of age, gender or the tooth involved were included in the study (11 males, 7 females; age range, 15-76 years; mean age, 44.7 years). The cases presented with acute or chronic apical abscess, with or without radiographic evidence of periapical pathology.

After written informed consent of the patient, access opening, cleaning and shaping of root canals by crown-down technique was done. The canals were copiously irrigated with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite. Depending on the extent of infection; either one or two inter-appointment dressing of triple antibiotic paste of metrogyl, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline was given. Special attention was given to apical third cleaning. Apical patency was maintained throughout the cleaning and shaping procedure. The apical third of the canal was debrided by “apical clearing” which involved its enlargement with 2-4 file sizes larger than the master apical file (MAF) at working length and removal of loose debris from the apical region.[6] Subsequent to this “apical foramen widening” was done with larger K-files used sequentially till size 25-30 to clean the cemental part of the canals. When the infection control was achieved, as evident from a clinically symptom-free tooth, healed swelling or sinuses, a final wash with an anti-microbial solution was done and the canals were dried. After checking the patency, determined by smooth passage of # 15 ISO instrument, intentional over-instrumentation into periapical region was done with #20 K-file to induce bleeding near the apical foramen. The file was gently given 2-3 clock-wise turns and then withdrawn by giving counter-clockwise rotation. A calcium sulphate-based cement (Cavit) was introduced in the access cavity and with a hand plugger, condensed into the cervical third of root canals. A suitable coronal restoration was given. Immediate post-treatment radiograph was taken. The patient was recalled every 6-months for clinical and radiographic evaluation. Pre and post treatment CBCT was done for six teeth in 3 cases who volunteered to undergo CBCT evaluation. All the cases were done on a single iCAT machine at 120 kvp, 5 mA with an exposure time of 7 seconds and voxel size of 0.25. The parameters evaluated were: lesion size, bone and cementum density in HU and periapical index (CBCT-PAI).

RESULTS

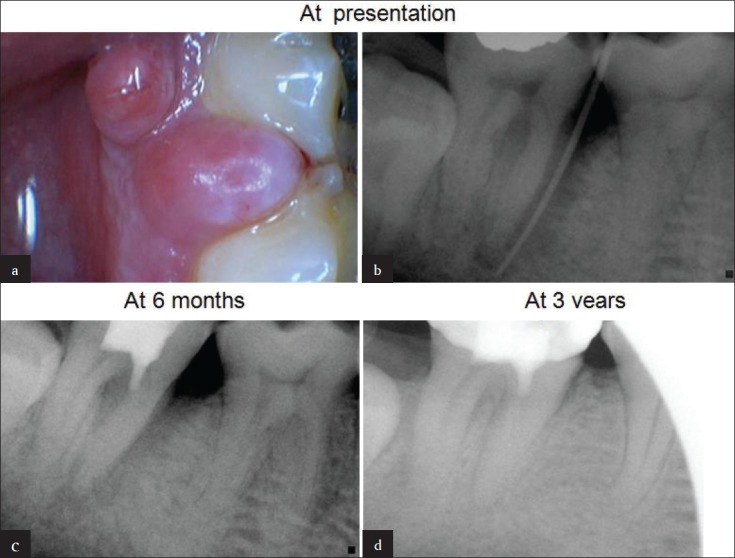

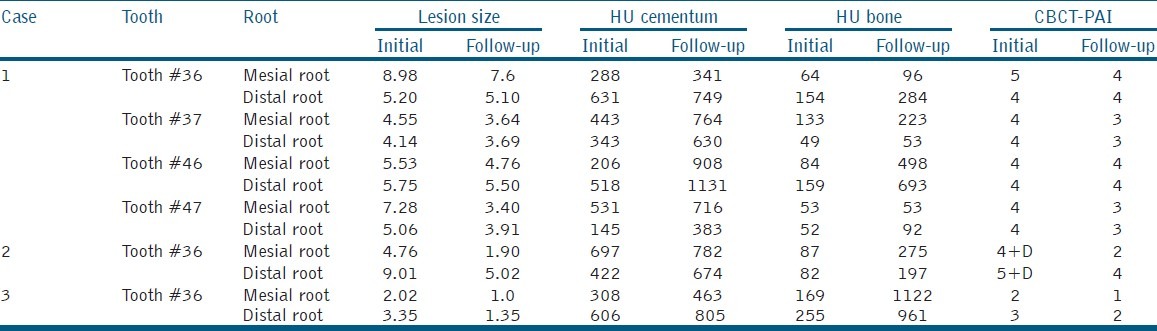

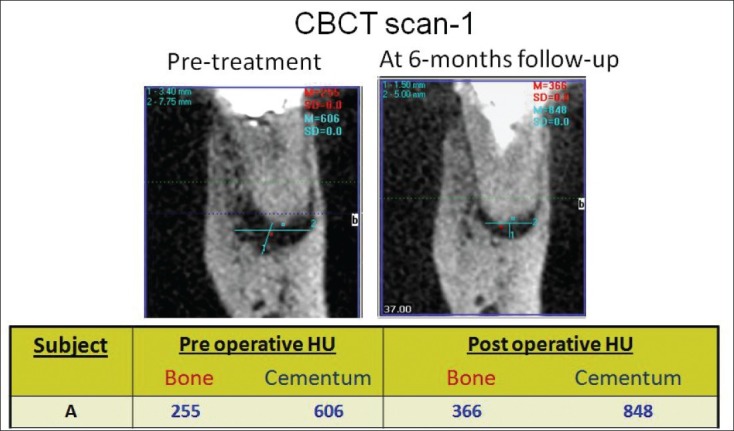

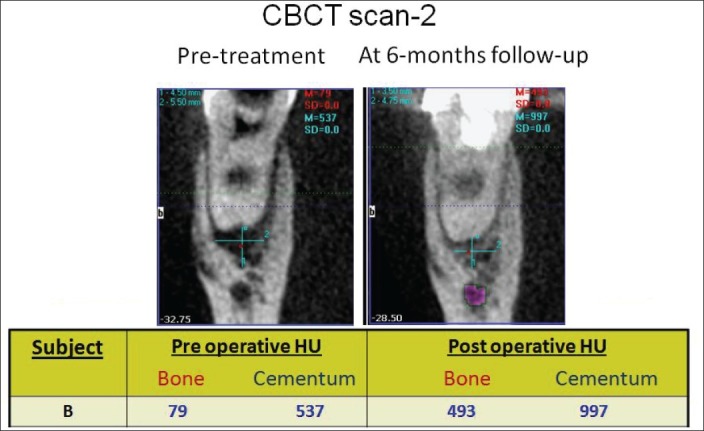

All the 18 cases treated by this novel endodontic treatment protocol showed very good response; both clinically as well as radiographically. Follow-up of 3 years was completed for 5 cases, 2 ½ years for 5 cases,;2 years for 5 cases and 6-months for 3 cases [Figures 1 and 2]. The soft tissue healing was excellent; intraoral sinus, buccal soft tissue swelling and bone expansion had completely resolved in all the cases. On radiographic examination, complete resolution or decrease in the size of periapical lesion was evident. In two cases of endo-perio lesion, marked healing of the periodontal defect was also seen. The CBCT findings are shown in Table 1. Remarkable decrease in the lesion size (CBCT-PAI) and increase in bone and cementum density {in Hounsfield unit (HU)} were documented [Figures 3 and 4].

Figure 1.

(a) A 53-year-old man presented with discrete soft tissue swellings at gingival margin in relation to # 47. (b) Sinus tract traced with guttapercha point documenting a pulpoperiodontal lesion. Note the bone loss on mesial aspect of mesial root. (c) Follow up X-ray at 6 months showing healing of periodontal defect. (d) At 3-years, complete healing and new bone regeneration in inter dental area between #46 and #47 is evident

Figure 2.

(a) Immediate post-treatment X-ray showing diffuse radiolucency around distal root in a 40-year-old man. (b) Just 6-weeks after the treatment, remarkable healing of the lesion is seen. (c) One-year follow-up x-ray showing complete healing

Table 1.

Showing result of CBCT evaluation of 6 teeth in 3 cases

Figure 3.

CBCT scan (i) & (ii) showing the pre and 6-months post treatment result

Figure 4.

CBCT scan (i) & (ii) showing the pre and 6-months post treatment result

DISCUSSION

The basis for success of endodontic treatment is to remove the cause, i.e. all necrotic debris, bacteria and their by products. As early as in 1939, it was known that the root canal was the seat of infection.[7] After debridement and disinfection of root canals, peri-radicular lesion had healed even without obturation of root canal.[8] Dubrow[9] in 1976 had argued that often treatment failures that were attributed to poor obturation could be the result of improper debridement. He also suggested that if canals were thoroughly debrided, healing of periapical tissues would occur and tissue fluid may not enter the canal space, even if it was not obturated. Dass[10] commenting on calcium hydroxide apexification had also stated that “perhaps filling is unessential and mere eradication of infection may be sufficient for apexification.” Role of thorough canal debridement and disinfection in periapical healing with incomplete obturation of root canals has been reported.[11] In an experimental animal study on dog's teeth reported in 2006, it was documented that there was no difference in healing of apical periodontitis with and without obturation, if root canals were thoroughly instrumented and debrided.[12]

In the recent past, the new treatment method of inducing revascularization in non-vital immature teeth has shown very encouraging results.[2–4] The present study was planned to determine whether a novel, non-surgical treatment protocol, based on regenerative principles, can be effective in fully mature teeth with pulp and periapical infection.

The argument given for complete 3-diemensional, fluid tight seal of the entire root canal system is that it will entomb the remaining microbes and also will not permit or at least delay the microbial infiltration, if there was leakage from the coronal restoration.[13] However, even after complete obturation, if coronal seal is broken for more than 3-4 weeks, it is recommended to perform retreatment, as during this period, bacteria would have colonized the pulp space and the tooth would develop endodontic infection sooner or later.[14]

Grossman in 1953 had stated that an optimal concentration of necrotic debris or toxic load is necessary to sustain or increase the periapical lesion.[15] It has also been concluded based on clinical and experimental animal studies that stagnant tissue fluid and sterile necrotic pulp tissue do not sustain inflammation at the periapex.[16]

Fabricius[17] had stated that permanent root canal filling, per se, had a limited effect on the outcome of endodontic treatment, if bacterial load was not controlled at the time of obturation. This exhaustive animal study adequately underlined the importance of thorough disinfection of canals rather than depend on high quality obturation for favorable outcome of endodontic treatment.

Siqueria[18] put forth the argument that for any species to cause disease, they have to reach a population density (load) conducive to cause tissue damage, either directly or by host tissue response to infection. Hence, clinically it is essential to reduce bacterial load to levels below that detected by culture procedures, i.e.103-104 cells. The treatment protocols should be so standardized that the bacterial count is brought to below this known threshold.

In the present study, heavy stress was laid on thorough disinfection of canal space and tight coronal seal. Special care was taken to clean the apical third of the canal space. Apical clearing, apical foramen widening and over-instrumentation into periapical region were done to induce bleeding near apical foramen. It is hypothesized that the clot formed provides a scaffold into which locally residing stem cells can get seeded and the cascade of healing process can initiate.

“Apical clearing” is a technique described to remove loose debris from the apical region by widening the apical canal with instruments 2-4 sizes larger than the master apical file (MAF) used at radiographic terminus without transportation of the canal or the apical foramen.[19] It is documented that in cases of apical periodontitis, intra-canal bacteria can penetrate dentin to a depth of 150-250 μ, where they remain protected from the action of medicament and irrigants.[20] Therefore, apical canal widening to 300-500 μ is required to thoroughly cleanse the apical portion of the canal.

Apical foramen widening was done with gradually increasing number of files till no #25 or #30. This allowed thorough cleaning of cemental part of the canal and also ensured subsequent smooth passage of instrument taken past the foramen without breakage.

Intentional over-instrumentation past the apical foramen into the periapical tissues contributes towards healing of the lesion as well as towards achieving biological barrier of hard and soft tissues as seen in cases of revascularization of immature teeth. This method of over-instrumentation was found very effective in resolution of periapical pathology in a prospective clinical study[21] by the first author in 1988.

Various stem cells reside in the periapical region of teeth such as periodontal ligament stem cells (SCPDL), dental pulp stem cells (DPSC), bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSC) and more recently identified stem cells from apical papilla (SCAP). These cells are now documented to play a role in maturogenesis of immature teeth using revascularization procedure.[22] It could be hypothesized that the same mechanism probably takes place in cases of mature teeth; the bleeding and clot formed in the area of apical foramen by over-instrumentation can lead to seeding of stem cells, their proliferation, differentiation and mineralized tissue formation, sealing the apical foramen.

The importance of a tight coronal seal cannot be over-emphasized. Without a coronal seal, bacteria and bacterial toxins can reach the apex through an obturated canal in just 20 days.[23,24] Cavit, a zinc-sulphate based material was chosen to seal the canal orifices. It served two purposes: (i) calcium sulphate cement is documented to have very good sealing properties[25] and (ii) in case retreatment was required, it would be easier to remove from canal orifices as compared to glass ionomer cement or mineral trioxide aggregate. Care was exercised in planning and placement of coronal restoration.

Although it has been suggested that reversal of healing process after non-surgical endodontic treatment is uncommon[26] and hence prolonged follow-up of cases showing healing may not be necessary.[27] Nevertheless, in the present study, a maximum follow-up of three years was possible and the cases are planned to be followed-up further.

The role of CBCT in evaluation of periapical healing has been reported.[28] It provides objective, non-invasive method to measure periapical healing and mineralized tissue deposition. CBCT evaluation of six teeth showed increased density of bone and cementum, supporting the hypothesis that mineralized barrier following this novel technique does take place.

Metzger Z and Abramowitz[29,30] reflecting on philosophy of endodontic treatment commented that “cleaning, shaping and preventing bacterial stimulation at root apices was taking a simplistic and mechanistic view. Endodontics should not limit itself to only better ways of cleaning, shaping and obturation. New concepts and methods, based on biological concepts must supplement traditional ones”. Tronstad also suggested the possibility of “Biological Obturation Technique” in future. The present innovative technique utilizing modified cleaning and shaping technique combined with regenerative, tissue engineering principles for treatment of infected, non-vital mature teeth is a step in this direction.

Further well-planned experimental animal studies can provide information on type of cells involved and tissue deposited. The evidence generated from this case-series also questions the role of obturation in non-surgical endodontic treatment. However, again, more evidence would need to be generated in the form of a randomized clinical trial to evaluate the role of obturation in view of recent advances in disinfection protocols, techniques and restorative materials.

CONCLUSION

The new technique, as discussed and documented in this pilot clinical study can prove to be the most simple, easy to perform and cost-effective method of regenerative endodontic treatment. The result proves the importance of thorough cleaning and shaping and a well-condensed, bacteria-tight coronal seal in endodontic treatment success. A small sub-set of six teeth evaluated by pre and post treatment CBCT has shown increased density of bone and cementum, supporting the premise that mineralized tissue deposition does occur at the root apex (hence sealing the apical end with biological tissue, i.e. SealBio).

DISCLAIMER

The views and opinion reported in this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the clinical standard of care policies of J Conserv Dent / IACDE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the administration and ethics committee of the All India Institute of Medical Science, New Delhi for permitting us to undertake this study. We also would like to acknowledge all the postgraduate students of the department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics for their support during the period of the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Voin ovich O, Voinovich J. Periodontal cell migration into the apical pulp during the repair process after pulpectomy in immature teeth: An auto radiographic study. J Oral Rehabil. 1993;20:637–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1993.tb01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwaya S, Ikawa M, Kubota M. Revascularization of an immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis and sinus tract. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17:185–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2001.017004185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchs F, Trope M. Revascularization of immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: New treatment protocol? J Endod. 2004;30:196–200. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah N, Logani A, Bhasker U, Aggarwal V. Revascularization for inducing apexogenesis/apexification in non-vital, immature permanent incisors: A pilot study. J Endod. 2007;34:919–25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matusow RJ. Acute pulpal-alveolar cellulitis syndrome V. Apical closure of immature teeth by infection control: Case report and a possible microbial-immunologic etiology. Part 1. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:737–42. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90285-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parris J, Wilcox L, Walton R. Effectiveness of apical clearing: Histological and radiographical evaluation. J Endod. 1994;20:219–24. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fish. Bone infections. J Amer J Dent Assoc. 1939;26:691. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingle JI, Bakland LK, Baumgartner JC. Endodontics. 6 ed. Ontario: B C Decker Inc; 2008. p. 922. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubrow H. Silver points and guttapercha and the role of root canal fillings. J Am Dent Assoc. 1976;93:976–80. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1976.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das S. Apexification in a non-vital tooth by control of infection. J Am Dent Assoc. 1980;100:880–1. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1980.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szajkis S, Taggar M. Periapical healing in spite of incomplete root canal debridement and filling. J Endod. 1983;9:203–9. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(83)80093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabeti MA, Nekofar M, Motabbary P, Ghandi M, Simon JH. Healing of apical periodontitis after endodontic treatment with and without obturation in dogs. J Endod. 2006;32:628–33. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saunders WP, Saunders EM. Coronal leakage as a cause of failure in root-canal therapy: A review. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1994;10:105–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1994.tb00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khayat A, Lee SJ, Torabinejad M. Human saliva penetration of coronally unsealed obturated root canals. J Endod. 1993;19:458–61. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman LI. Antibiotics vs instrumentation. A reply. N Y State Dent J. 1953;19:409. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klevant FJ, Eggink CO. The effect of canal preparation on periapical disease. Int Endod J. 1983;16:68–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1983.tb01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabricius L, Dahlén G, Sundqvist G, Happonen RP, Möller AJ. Influence of residual bacteria on periapical tissue healing after chemo-mechanical treatment and root filling of experimentally infected monkey teeth. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:278–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siqueria JF, Jr, Rocas IN. Clinical implications and microbiology of bacterial persistence after treatment procedures. J Endod. 2008;34:1291–130. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Card SJ, Sigurdsson A, Orstavik D, Trope M. The effectiveness of increased apical enlargement in reducing intra-canal bacteria. J Endod. 2002;28:779–83. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borlina SC, de Souza V, Holland R, Murata SS, Gomes-Filho JE, Dezan E, Junior, et al. Influence of apical foramen widening and sealer on the healing of chronic periapical lesions induced in dogs’ teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:932–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah N. Non-Surgical management of periapical lesions: A prospective Study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:3665–371. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gronthos S, Mankani M, Brahim J, Robey PG, Shi S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;7:13625–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240309797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heithersay GS. Stimulation of root formation in incompletely developed pulpless teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1970;29:620–30. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(70)90474-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beach CW, Calhoun JC, Bramwell JD, Hutter JW, Miller GA. Clinical evaluation of bacterial leakage of endodontic temporary filling materials. J Endod. 1996;22:459–62. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(96)80077-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vail MM, Steffel CI. Preference of temporary restorations and spacers: A survey of Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics. J Endod. 2006;32:513–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orstavik D. Time course and risk analysis of the development and healing of chronic apical periodontitis in man. Int Endod J. 1996;29:150–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1996.tb01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kvist T, Reit C. Results of Endodontic retreatment: A randomized clinical study comparing surgical and non-surgical procedures. J Endod. 1999;25:814–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(99)80304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Estrela C, Bueno MR, Azevedo BC, Azevedo JR, Pécora JD. A new periapical index based on cone beam computed tomography. J Endod. 2008;34:1325–31. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metzger Z, Abramovitz I. Periapical lesions of endodontic origin. In: Ingle JI, Bakland LK, Baumgartner JC, editors. Ingle's Endodontics. 6th ed. Ontario: BC Decker Inc; 2008. p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tronstad L. Clinical Endodontics: A Textbook. 2nd revised ed. New York: Thieme Stuttgart; 2003. p. 200. [Google Scholar]