Abstract

To present a unique case of mandibular second premolar with an atypical canal pattern. Thorough knowledge of root canal morphology, appropriate assessment of the pulp chamber floor, and critical interpretation of radiographs are a prerequisite for successful root canal treatment. Mandibular premolars frequently exhibit variable and complex root canal morphology and are one of the most difficult cases to treat endodontically. These teeth may require skillful and special root canal preparation and obturation techniques. This article reports an unusual case of a mandibular second premolar with atypical canal pattern that was successfully treated endodontically.

Keywords: Mandibular premolar, root canal morphology, root canal treatment

INTRODUCTION

Successful and predictable endodontic therapy depends on the complete cleaning and shaping of the entire root canal system followed by a three-dimensional obturation to create a fluid tight seal. To achieve this, a thorough knowledge of the of the root canal morphology and pulp chamber anatomy is a prerequisite. The root canal morphology of teeth is often extremely complex and highly variable.[1–3] A number of factors contribute to the variations found in the root canal morphology of permanent teeth like ethnic background, age, and gender of the population studied. Mandibular premolars exhibit a high frequency of complex and variable root canal morphology and for this reason they are one of the most difficult teeth to treat endodontically.[4–6] Over the years, numerous root canal patterns have been identified. In 1969, Weine et al.[7] provided the first clinical classification of more than one canal system in a single root using the mesiobuccal root of maxillary first molar as the specimen type. Pineda and Kuttler[8] and Vertucci[9] further developed a system for canal anatomy classification for teeth and classified them as Type I through Type VIII. Gulabivala et al.[10] studied the root canal morphology of mandibular molars and identified seven additional canal types according to the number of orifices, canals, and apical foramina. Sert and Bayirli[11] reported additional 14 new canal types (Type IX–Type XXIII). This article reports an unusual case of a mandibular second premolar with Type XVII (1-3-1) root canal pattern that was successfully treated with endodontic therapy.

CASE REPORT

A 30-year-old female patient reported to the department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics with the chief complaint of “pain in lower right back tooth.” Patient's medical history was non-contributory. Clinical examination revealed a carious lesion on the disto-occlusal surface of the crown of mandibular right second premolar [Figure 1]. The tooth was tender on percussion. Pulp vitality testing using electric pulp tester yielded a response at a higher current level than the adjacent and contralateral teeth that were clinically normal. Pre-operative radiograph of the tooth revealed a disto-occlusal carious lesion encroaching the pulp with slight widening of the apical periodontium. The most interesting radiographic finding was the unique pattern of the canal system [Figure 2]. It resembled the Sert and Bayirli's type XVII (1-3-1) canal system, that is, there was a single large canal orifice that divided into three canals and all the three root canals again joined in the apical one-third to form a single canal with a single apical foramen. Based on the clinical and radiographic findings, a diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis with apical periodontitis was made and it was decided to carry out multiple visit endodontic therapy with the tooth. The treatment plan was explained to the patient and after obtaining her consent, the tooth was anaesthetized with 2% lidocaine (Lignox A, Warren Indoco) solution by way of inferior alveolar nerve block of the right side. Subsequently, the tooth was isolated with rubber dam. Endodontic access cavity was prepared with round diamond burs in a high speed airotor handpiece. After extirpation of the pulpal tissue, a working length determination radiograph was obtained with K files (Dentsply, Maillefer) placed in the root canals. Following the working length determination, the root canals were prepared with a crown down technique with copious irrigation using 5% sodium hypochlorite solution. After completion of cleaning and shaping, the root canal system was obturated with cold lateral compaction of gutta percha cones using a resin-based sealer (AH plus, Dentsply). A post-obturation radiograph was obtained and the coronal access cavity was restored with silver amalgam. Interestingly, the patient's left mandibular premolars also exhibited atypical canal patterns.

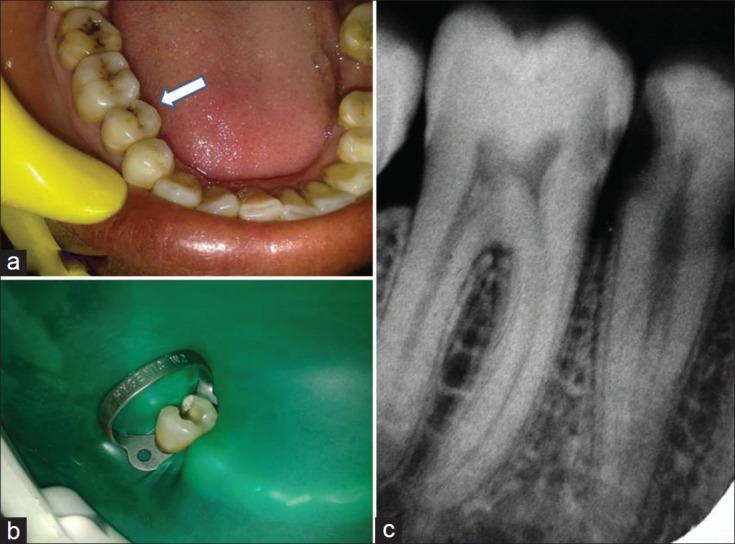

Figure 1.

(a) Pre-operative photograph of right mandibular second premolar. (b) Pre-operative radiograph of right mandibular second premolar. Note the atypical canal configuration. (c) .access cavity prepared

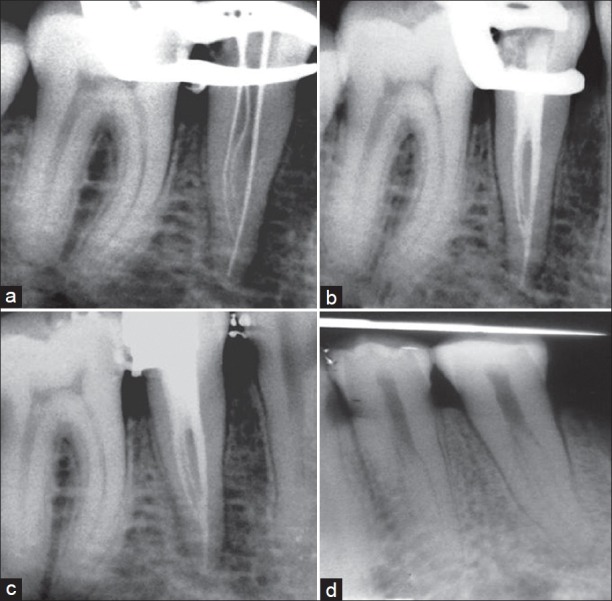

Figure 2.

(a) Working length-determination radiograph. (b) Immediate post-obturation radiograph. (c) Radiograph after coronal silver-amalgam restoration. (d) Radiograph of left mandibular premolars. Note the atypical canal configuration.

DISCUSSION

The root canal morphology of mandibular premolars can be highly variable and complex and it is often a challenging task to carry out successful endodontic therapy with such teeth. Therefore, the primary step in root canal treatment is the identification of the internal morphology of canal system as precisely as possible. To obtain predictable results, high-quality pre-operative radiographs should be obtained at different horizontal angulations and carefully evaluated to detect the presence of extra root canal.[12,13] The prevalence of three root canals in mandibular premolars have been reported to be 0.4% by Zillich and Dowson.[14] The root shape, root position, and relative root outline should be carefully determined from the radiograph. The observations made in a study[10] concluded that broad, flat roots are much more likely to contain multiple canals and intercanal ramifications. In such cases, angled radiographic view will reveal the true dimensions of the root canal. The sudden radiographic disappearance of a canal may be evidence of a dividing canal. As radiographs are a two-dimensional representation of three-dimensional objects, at times it is difficult to clearly and completely determine the root canal configuration. In such cases, advanced imaging techniques like cone-beam computed tomography are very helpful. Using this technique, images can be obtained in almost any plane of section in the entire three dimensions. Even in the presence of such technology, the careful tactile exploration of the root canal system with hand files is imperative. In the present case, although the root canal morphology was complex, it was clearly determined on the preoperative radiograph. After identification, proper cleaning and shaping of the root canals should be carried out followed by complete obturation of all the canals to achieve a predictable long-term endodontic prognosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ash M, Nelson S. Wheeler's Dental Anatomy, Physiology and Occlusion. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown P, Herbranson E. Dental Anatomy and 3D Tooth Atlas Version3.0. 2nd ed. Illinois: Quintessence; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor R. Variations in Morphology of Teeth. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Pub; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slowey RR. Root Canal Anatomy. Road map to successful endodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 1979;23:555–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nallapati S. Three canal mandibular first and second premolars: A treatment approach. J Endod. 2005;31:474–6. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000157986.69173.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poorni S, Karumaran CS, Indira R. Mandibular first premolar with two roots and three canals. Aust Endod J. 2010;36:32–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2009.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weine FS, Healey HJ, Gerstein H, Evanson L. Canal configuration in the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar and its endodontic significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1969;28:419–25. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(69)90237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pineda F, Kuttler Y. Mesiodistal and buccolingual roentgenographic investigation of 7,275 root canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972;33:101–10. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vertucci FJ. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:589–99. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulabivala K, Aung TH, Alavi A, Ng YL. Root and canal morphology of Burmese mandibular molars. Int Endod J. 2001;34:359–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2001.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sert S, Bayirli GS. Evaluation of the root canal configurations of the mandibular and maxillary permanent teeth by gender in the Turkish population. J Endod. 2004;30:391–8. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200406000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.England MC, Jr, Hartwell GR, Lance JR. Detection and treatment of multiple canals in mandibular premolars. J Endod. 1991;17:174–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)82012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hulsmann M. Mandibular first premolar with three root canals. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1990;6:189–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1990.tb00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zillich R, Dowson J. Root canal morphology of mandibular first and second premolars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;36:738–44. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(73)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]