Abstract

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the skin and muscles. Evidence supports that DM is an immune-mediated disease and 50–70% of patients have circulating myositis-specific auto-antibodies. Gene expression microarrays have demonstrated upregulation of interferon signaling in the muscle, blood, and skin of DM patients. Patients with classic DM typically present with symmetric, proximal muscle weakness, and skin lesions that demonstrate interface dermatitis on histopathology. Evaluation for muscle inflammation can include muscle enzymes, electromyogram, magnetic resonance imaging, and/or muscle biopsy. Classic skin manifestations of DM include the heliotrope rash, Gottron's papules, Gottron's sign, the V-sign, and shawl sign. Additional cutaneous lesions frequently observed in DM patients include periungual telangiectasias, cuticular overgrowth, “mechanic's hands”, palmar papules overlying joint creases, poikiloderma, and calcinosis. Clinically amyopathic DM is a term used to describe patients who have classic cutaneous manifestations for more than 6 months, but no muscle weakness or elevation in muscle enzymes. Interstitial lung disease can affect 35–40% of patients with inflammatory myopathies and is often associated with the presence of an antisynthetase antibody. Other clinical manifestations that can occur in patients with DM include dysphagia, dysphonia, myalgias, Raynaud phenomenon, fevers, weight loss, fatigue, and a nonerosive inflammatory polyarthritis. Patients with DM have a three to eight times increased risk for developing an associated malignancy compared with the general population, and therefore all patients with DM should be evaluated at the time of diagnosis for the presence of an associated malignancy. This review summarizes the immunopathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and evaluation of patients with DM.

Keywords: Cutaneous manifestations, dermatomyositis, diagnosis

Introduction

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the skin and muscles. Although it is considered an autoimmune disease, questions remain regarding the etiopathogenesis. Skin involvement in DM usually manifests with characteristic papules over digits, erythema over the elbows and knees, a heliotrope rash around the eyes, periungual telangiectasias, and dystrophic cuticles.[1] Muscle involvement usually manifests as proximal muscle weakness initially, with or without myalgias or tenderness. An amyopathic variant with minimal to no muscle inflammation has been described.[2] There is a well-established association of DM with an increased risk of internal malignancy.[3] Other important clinical features of DM include the presence of interstitial lung disease (ILD).[4–6] In this review, we will discuss the clinical features and initial evaluation of DM in adults.

Comprehensive epidemiologic data are lacking for determining the true incidence and prevalence of DM. Most studies are limited by marked variations according to age, sex, and region.[7] In addition, most epidemiologic studies pool analyses of autoimmune myopathies, use stricter definitions of disease, and rely on physician billing and hospitalization databases, which may not accurately represent the true population. However, Bendewald et al. recently published data from a retrospective 32 year population-based study from Olmsted, Minnesota showing that the overall age- and sex-adjusted incidence of DM was about 1 per 100,000 people per year with an estimated prevalence calculated to be about 20 cases per 100,000 people.[8] About 20% of patients in this study were clinically amyopathic with an age- and sex-adjusted incidence of 1 per 1 million people. DM has a bimodal distribution in the age of onset, occurring in two peaks, one at 5–14 years and the other at 45–64 years of life. The disease affects women approximately two to three times more than men.

Immunopathogenesis

There is ample evidence that DM is an immune-mediated disorder, given the immunohistopathology and given the response to immunosuppression. The typical histopathologic findings of DM in muscle include perifascicular atrophy, endothelial cell swelling, vessel wall membrane attack complex (MAC) deposition, capillary necrosis, infarcts, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I upregulation, and the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate consisting of T and B lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells.[9] There are findings of predominant perimysial and perivascular B/CD4+ T cell infiltrate and intravascular MAC deposition. Recent studies have provided evidence that 30–90% of the CD4+ cells found in DM muscle are actually plasmacytoid dendritic cells.[10]

The typical histopathologic findings in DM skin include epidermal basal cell vacuolar degeneration, apoptosis of epidermal basal and suprabasal cells often with epidermal atrophy, and increased dermal mucin deposition.[11] A cell-poor interface dermatitis comprised of plasmacytoid dendritic cells at the dermal–epidermal junction is also characteristic. Features that are more specific to DM over cutaneous lupus include C5b-deposition in both dermal vasculature and the dermal-epidermal junction and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.[12]

DM has traditionally been viewed as a humorally mediated vasculopathic disease given the findings of autoantibodies and complement deposition in vessels.[13] The proposed mechanism has been that binding of antibodies targeting the endothelium of the endomysial capillaries leads to activation of the complement system with subsequent MAC deposition. This in turn may lead to endothelial swelling, capillary necrosis, perivascular inflammation, and muscle ischemia. Relative hypoperfusion of the perifascicular regions is thought to explain the findings of atrophy in this region on muscle biopsy. This model of DM pathogenesis, however, is unproven.[14] Certain limitations to this model include the absence of an identified pathogenic antibody against an endothelial antigen, and the unclear relationship between capillary injury and perifascicular atrophy, since the perifascicular area has not been shown to be specifically vulnerable to ischemia.[14]

Data using gene expression microarrays have demonstrated upregulation of interferon signaling in the muscle, blood, and skin of DM patients.[15] In muscle, almost 90% of the highly expressed gene transcripts in DM compared with controls belong to genes that are induced by the type 1 interferons.[15] In addition, the finding that plasmacytoid dendritic cells are present in skin and muscle of DM patients, implicates these cells as potential sources of the interferons. Based on these findings, Greenberg has proposed a revised model of DM wherein endothelial cells and myofibers may be injured by the chronic overproduction intracellularly of one or more interferon α/β inducible proteins.[15] It has been proposed that interferons produced by plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which are typically found in higher concentration in perimysial regions, may contribute to perifascicular atrophy. What still remains unclear is what might be driving the transcription of interferon α/β inducible genes and whether viral DNA and RNA substrates could potentially be activating the plasmacytoid dendritic cells.

Diagnosis

The most commonly used criteria for the diagnosis and classification of DM and PM was defined by Bohan and Peter in 1975.[16] In classic DM, in addition to cutaneous manifestations and proximal muscle weakness, patients have abnormal muscle enzymes (creatine kinase [CK], aldolase, aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], and/or lactate dehydrogenase [LDH]). Electromyogram (EMG) studies are useful early in disease and show abnormal findings in 70–90% of cases but are nonspecific and can be seen in other muscle diseases. Typical EMG findings include increased spontaneous and insertional activity with fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, complex repetitive discharges, early recruitment, and small polyphasic motor until potentials.[17] Imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a sensitive technique for evaluation of myositis with the presence of muscle edema. Areas of inflammation are hyperintense on T2-weighted images with clearer images seen with fat suppression or short tau inversion recovery sequences.[18] In late disease, muscle atrophy can be seen. Muscle and/or skin biopsies are required to make a definite diagnosis and to rule out other disease mimickers. The muscle biopsy should be obtained from moderately weak muscle areas as assessed by physical exam, areas of inflammation located by MRI, or muscles contralateral to those identified as abnormal on EMG.

Clinical Manifestations of DM

Muscle disease

DM presents with a varying degree of muscle weakness that is insidious in onset and gradually worsens over weeks to months, but a more fulminant progression can occur. The initial presentation of muscle involvement is typically symmetric and proximal, with distal muscle weakness occurring late in the course of the disease. Patients often have difficulty with activities such as rising from a chair, climbing stairs, lifting objects, or washing their hair. Difficulty holding and manipulating objects can occur with distal muscle involvement. When the neck extensor muscles are involved, patients can present with head drop. With more severe disease, patients can develop dysphagia, dysphonia, and weakness in the muscles of respiration. Myalgias and muscle tenderness are less common but can occur in up to 30% of patients.[19]

Skin disease

The characteristic rash of DM can occur before, shortly after, or at the same time as muscle weakness. As mentioned above, a proportion of patients will have the characteristic cutaneous findings of DM, and never develop clinical or laboratory signs of myositis. A hallmark sign of DM are Gottron's papules [Figure 1a]. These lesions primarily consist of erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques over the extensor surfaces of the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints. These lesions may have accompanying scale, and can sometimes develop ulcerations; active lesions tend to resolve with dyspigmentation, atrophy, and scarring. Gottron's sign refers to erythematous macules and patches overlying the elbows and/or knees, and are less specific findings for DM [Figure 1b].[20] Another hallmark sign of DM is the heliotrope rash which consists of violaceous erythema of the upper eyelids often with associated edema and telangiectasia. It should be noted that in darker skin types, this erythema may be subtle and overlooked. Erythematous patches and/or plaques in other characteristic sun-exposed or nonsun-exposed areas may also be seen in DM. A confluent erythema in the malar distribution involving the cheeks and extending over the nasal bridge may be seen, and can often involve the nasolabial folds. More extensive involvement can be seen in other areas including the forehead, lateral face, and ears. Confluent macular erythema over the lower anterior neck and upper anterior chest can also be seen (the so-called “V” sign) [Figure 1c]. A shawl sign refers to erythema over the upper back, posterior neck, and shoulders, sometimes with extension to the lateral arms [Figure 1d]. Nonsun-exposed areas can also be involved, especially the scalp [Figure 1e], lower back, and lateral thighs (Holster sign).[20] Erythroderma with extensive areas of confluent erythema involving over 50% of the body surface area is rare. Also rarely, patients can present with a more ichthyotic variant which appears as severely dry and cracked skin.

Figure 1.

(a) Gottron's papules: Violaceous, scaling papules on the skin overlying the joints and proximal nailfolds. (b) Gottron's sign: Violaceous patches overlying the knees. (c) “V neck” sign: Erythematous and hyperpigmented macules on the chest. (d) Shawl sign: Violaceous macules and patches on the upper back and shoulders. (e) Scalp disease in dermatomyositis: Deeply erythematous scaling plaques are seen diffusely on the posterior scalp

Vasculopathic lesions of DM include livedo reticularis, ulceration [Figure 2a], and telangiectasia (including gingival and periungual) [Figure 2b]. On nailfold capillary examination, DM patients can have prominent dilated and tortuous blood vessels accompanied by avascular areas. The degree of telangiectasias and vessel drop-out reflects ongoing disease activity, particularly in the skin.[21]

Figure 2.

(a) Shallow, crusted erosions arising in an area of intense inflammation. (b) Telangiectatic macules and papules on the breast in a patient with longstanding disease

Characteristic hand lesions include rough and cracked, hyperkeratotic, “dirty” horizontal lines on the lateral and palmer areas of the fingers, resembling “mechanics” hands [Figure 3a]. Cuticular overgrowth and irregularity on the nail plate can also be observed [Figure 3b]. Palmar and plantar erythema occasionally associated with a mottled appearance may be indicative of vascular instability in DM patients. In addition, raised, often tender papules or plaques can be present overlying joint creases of the palmar hands. On biopsy, these lesions demonstrate mucin deposition in the dermis.

Figure 3.

(a) Mechanic hands: Erythematous, scaling papules located on the lateral aspect of the second and third digits. (b) Overgrown cuticles are seen containing multiple hemorrhages. (c) Multifocal, discrete areas of nonscarring alopecia on the posterior scalp

Other potentially significant cutaneous features of DM include panniculitis, alopecia (focal, due to areas of inflammation on the scalp, or diffuse) [Figure 3c], and flagellate erythema (linear streaks in the upper back occurring in association with excoriations from pruritus).[20] Poikiloderma is a manifestation of disease chronicity with a mottled pattern of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules interspersed with telangiectasias [Figure 2b]. Lastly, calcinosis involving the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia, or muscle seen in areas of potential trauma or inflammation is often a late complication, seen more often in juvenile than in adult cases.

Lung disease

ILD is a significant source of morbidity and mortality in patients with inflammatory myositis. It has been estimated that about 35–40% of patients with either polymyositis or dermatomyositis will suffer from ILD during the course of their illness.[4] Large case series have suggested that over 75% of patients who have an antisynthetase antibody will develop ILD,[22] however, a small prospective longitudinal study suggested that anti-Jo antibody positivity may portend a better ILD progrosis.[23] Clinically amyopathic DM can also be associated with ILD, and several studies have reported that rapidly progressive ILD is observed more frequently in this subgroup of patients.[24]

Patients with ILD present with subjective dyspnea on exertion, cough, and decreased exercise tolerance. The clinical course has been described as one of three patterns: Acute, severe involvement; chronic slowly progressive symptoms; or asymptomatic disease in which abnormal imaging indicates the presence of lung involvement.[25] Muscle disease typically precedes the onset of lung disease but this is not always the case.[22]

Pulmonary function testing typically reveals a restrictive disease pattern (forced vital capacity [FVC] or total lung capacity [TLC] <80% predicted for age) or a decrease in diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO). However, a diagnosis of ILD requires a confirmatory imaging study since the findings on pulmonary function testing can also be seen with respiratory muscle weakness alone. A relatively preserved DLCO with a restrictive physiology would favor respiratory muscle weakness. A recent study also suggests that up to 25% of patients may have only isolated deficiency in DLCO with no other defects on pulmonary function testing.[26] High-resolution CT (HRCT) scanning is very sensitive for the detection of ILD and can be helpful to follow disease progression. Characteristic features on HRCT include nodules, linear opacities, fibrosis with or without honeycombing, consolidation, traction bronchiectasis, and bronchiolectasis. While earlier studies suggested that ground glass opacities were more responsive to therapy, recent studies suggest that patients with these findings have a poorer prognosis compared with patients with predominantly fibrotic disease.[22] Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage is helpful to rule out occult infections in patients who are chronically immunosuppressed. The role of surgical lung biopsy is unclear—studies evaluating the prognostic utility of biopsy subtypes have not yielded firm conclusions, and further research in this area is needed.

Other manifestations

Esophageal disease in DM patients most commonly presents with dysphagia to solids and liquids due to loss of pharyngo–esophageal muscle tone. Other signs of pharyngo–esophageal involvement include nasal speech, hoarseness, nasal regurgitation, and aspiration pneumonia. A diagnosis can be confirmed by manometry with low amplitude/absent pharyngeal contractions and decreased upper esophageal sphincter pressures.[27]

Cardiac muscle involvement in DM is usually subclinical. Most commonly, isolated electrocardiographic changes are noted that are not clinically significant. Valvular abnormalities have also been described, as well as reports of congestive heart failure at the onset of myositis or during the course of disease, but these complications are rare. Autopsy studies of cardiac biopsy data in asymptomatic patients have revealed myocarditis in about 30% of DM patients with histology very similar to that observed in skeletal muscles.[28] Although cardiac involvement can occur in DM, more often than not, patients are asymptomatic, and therefore there are no guidelines for screening for cardiac involvement in DM patients.[29]

Other manifestations of DM include Raynaud phenomenon, fevers, weight loss, fatigue, and a nonerosive inflammatory polyarthritis.

Clinically Amyopathic DM

The term amyopathic DM was proposed to describe patients who have classic cutaneous manifestations for more than 6 months without clinical, laboratory, or other muscle testing evidence of myopathy, whereas hypomyopathic DM patients could have abnormalities on further muscle evaluation without clinical or laboratory abnormalities.[30]

The term clinically amyopathic DM (CADM) is now being used as an umbrella term that combines the amyopathic and hypomyopathic DM patients. These patients clinically have neither muscle weakness nor significant muscle enzyme elevation—thus, they are termed clinically amyopathic. Other studies (such as EMG, MRI, or muscle biopsy) may or may not show abnormalities. These patients would be considered conditionally amyopathic if they are being treated with systemic immunosuppressive agents (which may mask myositis) or have had the cutaneous rash for less than 6 months, since classic DM patients can often experience a lag period before weakness develops.[30]

It has been estimated that 10–20% of patients with DM seen in dermatology referral clinics in the US have amyopathic DM.[31] However, estimates may be higher at certain centers. For example, Klein et al. found that 67% (56/83) of patients seen at the University of Pennsylvania dermatology clinics had CADM when combining patients with amyopathic and hypomyopathic disease.[32] The first population-based study from Olmstead county Minnesota found that 21% of their DM patients (n=6/29) had CADM.[8] Patients with CADM were predominantly of adult-onset, female, and white race. Three patients (10%) who were originally CADM evolved into clinical DM and were not included amongst the six CADM classified patients. Gerami et al. performed a systematic review and found that 37 of 291 (13%) reported cases of adult-onset CADM patients developed muscle weakness at 15 months to 6 years after onset of their skin disease. This suggests that patients with CADM need to be monitored long-term for development of muscle disease.[30] They also noted that 13% of CADM patients had interstitial pneumonitis and 14% had an associated malignancy. From this study it is unclear if these risks differ between the classic and CADM populations. Data from the Japanese literature, however, suggests that CADM is associated with more rapidly progressive ILD than that seen in classic DM patients.[24]

Malignancy

The association of DM with malignancy has now been studied in several case-control and population-based studies. Large population-based epidemiologic studies from Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Scotland, Australia, and Taiwan have shown an overall increased standardized incidence ratio (SIR) from 3.8 to 7.7 for malignancies at the same time or after the diagnosis of myositis with a frequency from 9% to 42%.[33] The risk of malignancy was highest at the time of or within 1 year of diagnosis of myositis. Most of these studies relied on accuracy of discharge coding and did not require histologic proof of diagnosis thus somewhat limiting their accuracy.

Pooled data from three published national databases from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland by Hill et al. looked at the frequency of specific cancer types in DM.[34] They found 198 malignancies in 618 cases of DM with an overall SIR of 3.0 (95% CI 2.5–36). SIR for particular cancer types were as follows: Ovarian (10.5), lung (5.9), pancreatic (3.8), stomach (3.5), colorectal (2.5), and nonHodgkin's lymphoma (3.6).

Various case series have identified clinical risk factors for malignancy in DM, although there is some discrepancy with these data. Sparsa et al. found the presence of constitutional symptoms, absence of Raynaud's phenomenon, and high ESR to be associated with occurrence of malignancy in their cohort of 40 patients.[35] Another study identified the following as associated with a higher risk of malignancy: older age at onset of disease, more severe skin disease with cutaneous necrosis and ulceration, more severe muscle disease with distal weakness, dysphagia, and respiratory muscle involvement.[33]

Recently, a myositis specific antibody reactive with 155- and 140-kDa nuclear protein (anti-p155/140) has been identified that appears to be associated with malignancy in adult DM patients.[36,37] A meta-analysis of six published studies on this antibody, showed that patients who tested positive for the p155 antibody had an 18-fold higher association with cancer than p-155 antibody negative patients, with an overall specificity of 89%, sensitivity of 70%, and negative predictive value of 93%.[38]

All patients with DM should be evaluated at diagnosis for the presence of an associated malignancy. The workup should start with a careful history and physical examination, including a rectal examination, breast and pelvic examination in women, and testicular examination in men. Other age appropriate evaluations for malignancy should be updated, including mammograms and Pap smears in women, prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels in men. All patients over the age of 50 years should have a colonoscopy. Beyond this, there is controversy about the utility of additional malignancy screening techniques. Given the fact that ovarian cancer occurs with a relatively high frequency in association with DM, periodic pelvic and transvaginal ultrasounds may be worthwhile. Data from Sparsa et al. suggest that screening CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis may be useful in detecting cancers that would otherwise be missed.[35] Other cancer screening tests should be dictated by patient symptoms or ethnic background. For example, in patients of Chinese descent, a search for nasopharyngeal cancer should also be performed. Moreover, a recurrence of myositis or rash after an initial response to treatment should prompt consideration for a search for malignancy.

Autoantibodies and Associated Clinical Features

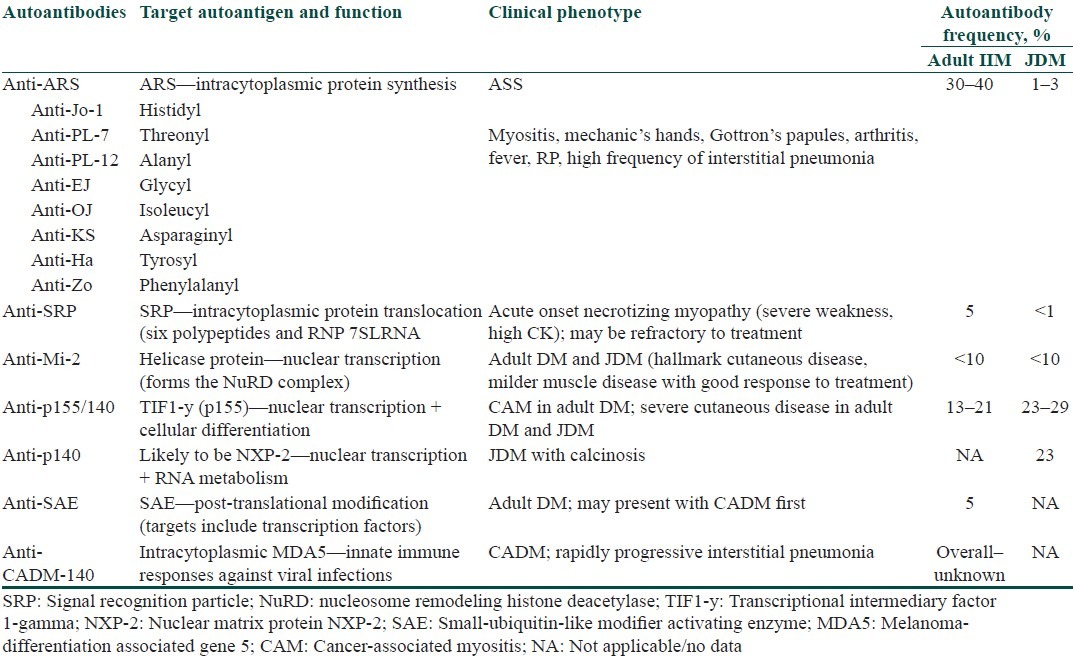

As in other autoimmune diseases, there has been a strong association of autoantibodies with clinical features in patients with inflammatory myositis [Table 1]. Myositis-specific antibodies (MSAs) are found almost exclusively in patients with myositis, whereas myositis-associated antibodies can be seen in other connective tissue diseases as well. MSAs are antibodies to nuclear or cytoplasmic antigens and are found circulating in approximately 50–70% of DM patients.[39] It remains unclear whether these antibodies have a pathogenic role in the disease process.

Table 1.

Myositis-specific autoantibodies, autoantigen targets, and clinical features. Re-printed with permission from reference[39]

There are several MSAs to unique synthetase proteins, including Jo-1, PL-7, PL-12, EJ, OJ, KS, and Zo. The most common antibody found in myositis patients overall (but uncommonly seen in DM patients) is the anti-Jo-1 antibody, which targets histidyl-tRNA synthetase, and is associated with the “antisynthetase syndrome” comprised of fever, inflammatory arthritis, Raynaud's phenomenon, and ILD. Mechanic's hands are cutaneous markers for this entity but can also be seen in patients who do not have antisynthetase antibodies. Although myositis-specific, these antibodies are not commonly seen in DM (0–15%).[5]

Other MSAs are largely restricted to DM patients. The first to be discovered was the antibody to Mi-2, a nuclear helicase protein, which is seen in 20–30% of DM patients. This antibody has been associated with a relatively good prognosis, a reduced risk of ILD, a more reliable response to steroids, and a diminished incidence of malignancy.[5] Adults with anti-Mi-2 generally have classic cutaneous features with pathognomic heliotrope, Gottron's papules, V-sign, shawl sign, and cuticular overgrowth.

Another DM-specific MSA was recently identified, which is reactive to 155 and 140 kDa proteins.[37,40] Anti p155/140 antibodies are found to be highly specific for DM and relatively common, seen in 13–21% of DM patients.[37,40] These antibodies are associated with more severe cutaneous involvement and a markedly higher rate of malignancy—71% in antibody positive vs 11% in antibody negative patients. Additional studies have confirmed the association of anti p155/140 with increased malignancy rates in other cohorts.[41]

Recently, in a Japanese cohort of CADM patients with rapidly progressive ILD, an antibody to a 140 kDa protein was identified in 19–35% of patients with DM.[42] The antibody was termed CADM 140 but subsequently the autoantigen was identified as the cytoplasmic protein melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA- 5) involved in innate immune responses against viral infections. Patients with MDA-5/CADM-140 have amyopathic disease with a higher prevalence of rapidly progressive ILD. Looking at a different cohort of mostly Caucasian patients, Fiorentino et al. have also found that this antibody tends to occur in patients with ILD and mild muscle involvement.[43] In addition, these patients are characterized by cutaneous ulceration, palmar papules over the finger creases, alopecia, and arthritis/arthralgia.[43]

Another novel MSA that appears to be DM-specific was reported from the UK that recognizes a small ubiquitin-like modifier autoantigen (anti-SAE) that is involved in posttranslational modification.[44] It was found in the sera of 8.4% of DM cases who had clinical features of CADM initially, and then progressed to myositis with higher incidence of dysphagia and lower rates of ILD. Additional cohorts need to be analyzed to better define the prevalence and clinical features associated with this antibody.

Conclusion

In this review, we have highlighted the clinical presentation and evaluation of DM. It is important to recognize that DM is a unique disease in the category of idiopathic inflammatory myositis with very characteristic skin involvement. There are important clinical manifestations that can be associated with DM, including pulmonary involvement with ILD and malignancy. We have also reviewed recent studies on CADM that show that these patients can develop lung involvement and malignancies like classical DM patients, and need to be monitored long-term for the development of muscle inflammation. Finally, we have reviewed the diagnostic evaluation for patients with DM, including a review of the MSAs and their associated clinical phenotypes. Further research investigating the etiopathogenesis of this complex disease will hopefully shed light on DM susceptibility, heterogeneity, and progression..

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Callen JP, Wortmann RL. Dermatomyositis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:363–73. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sontheimer RD. Would a new name hasten the acceptance of amyopathic dermatomyositis (dermatomyositis sine myositis) as a distinctive subset within the idiopathic inflammatory dermatomyopathies spectrum of clinical illness? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:626–36. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madan V, Chinoy H, Griffiths CE, Cooper RG. Defining cancer risk in dermatomyositis.Part I. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:451–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fathi M, Lundberg IE, Tornling G. Pulmonary complications of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:451–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mammen AL. Dermatomyositis and polymyositis: Clinical presentation, autoantibodies, and pathogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:134–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearson C. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. In: McCarty DJ, editor. Arthritis and Allied Conditions: A Textbook of Rheumatology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernatsky S, Joseph L, Pineau CA, Bélisle P, Boivin JF, Banerjee D, et al. Estimating the prevalence of polymyositis and dermatomyositis from administrative data: Age, sex and regional differences. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1192–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.093161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bendewald MJ, Wetter DA, Li X, Davis MD. Incidence of dermatomyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis: A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:26–30. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalakas MC. Muscle biopsy findings in inflammatory myopathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2002;28:779–98. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(02)00030-3. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg SA, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Burleson T, Sanoudou D, Tawil R, et al. Interferon-alpha/beta-mediated innate immune mechanisms in dermatomyositis. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:664–78. doi: 10.1002/ana.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costner MI, Jacobe H. Dermatopathology of connective tissue diseases. Adv Dermatol. 2000;16:323–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magro CM, Crowson AN. The immunofluorescent profile of dermatomyositis: A comparative study with lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:543–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1997.tb01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalakas MC. Autoimmune inflammatory myopathies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2007;86:273–301. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)86014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg SA, Amato AA. Uncertainties in the pathogenesis of adult dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:359–64. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200406000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg SA. Dermatomyositis and type 1 interferons. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12:198–203. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0101-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502132920706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briani C, Doria A, Sarzi-Puttini P, Dalakas MC. Update on idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Autoimmunity. 2006;39:161–70. doi: 10.1080/08916930600622132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimball AB, Summers RM, Turner M, Dugan EM, Hicks J, Miller FW, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging detection of occult skin and subcutaneous abnormalities in juvenile dermatomyositis. Implications for diagnosis and therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1866–73. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1866::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362:971–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sontheimer RD. Dermatomyositis: An overview of recent progress with emphasis on dermatologic aspects. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:387–408. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith RL, Sundberg J, Shamiyah E, Dyer A, Pachman LM. Skin involvement in juvenile dermatomyositis is associated with loss of end row nailfold capillary loops. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1644–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connors GR, Christopher-Stine L, Oddis CV, Danoff SK. Interstitial lung disease associated with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: What progress has been made in the past 35 years? Chest. 2010;138:1464–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fathi M, Vikgren J, Boijsen M, Tylen U, Jorfeldt L, Tornling G, et al. Interstitial lung disease in polymyositis and dermatomyositis: Longitudinal evaluation by pulmonary function and radiology. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:677–85. doi: 10.1002/art.23571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato S, Kuwana M. Clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:639–43. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833f1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fathi M, Lundberg IE. Interstitial lung disease in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:701–6. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000179949.65895.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morganroth PA, Kreider ME, Okawa J, Taylor L, Werth VP. Interstitial lung disease in classic and skin-predominant dermatomyositis: A retrospective study with screening recommendations. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:729–38. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebert EC. Review article: The gastrointestinal complications of myositis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:359–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lie JT. Cardiac manifestations in polymyositis/dermatomyositis: How to get to heart of the matter. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:809–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bazzani C, Cavazzana I, Ceribelli A, Vizzardi E, Dei Cas L, Franceschini F. Cardiological features in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2010;11:906–11. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32833cdca8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerami P, Schope JM, McDonald L, Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. A systematic review of adult-onset clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (dermatomyositis siné myositis): A missing link within the spectrum of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:597–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jorizzo JL. Dermatomyositis: Practical aspects. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:114–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein RQ, Teal V, Taylor L, Troxel AB, Werth VP. Number, characteristics, and classification of patients with dermatomyositis seen by dermatology and rheumatology departments at a large tertiary medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:937–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zahr ZA, Baer AN. Malignancy in myositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13:208–15. doi: 10.1007/s11926-011-0169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, Pukkala E, Mellemkjaer L, Airio A, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: A population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96–100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sparsa A, Liozon E, Herrmann F, Ly K, Lebrun V, Soria P, et al. Routine vs extensive malignancy search for adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: A study of 40 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:885–90. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan FK, Arnett FC, Antohi S, Saito S, Mirarchi A, Spiera H, et al. Autoantibodies to the extracellular matrix microfibrillar protein, fibrillin-1, in patients with scleroderma and other connective tissue diseases. J Immunol. 1999;163:1066–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Targoff IN, Mamyrova G, Trieu EP, Perurena O, Koneru B, O’Hanlon TP, et al. A novel autoantibody to a 155-kd protein is associated with dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3682–9. doi: 10.1002/art.22164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selva-O’Callaghan A, Trallero-Araguás E, Grau-Junyent JM, Labrador-Horrillo M. Malignancy and myositis: Novel autoantibodies and new insights. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:627–32. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833f1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunawardena H, Betteridge ZE, McHugh NJ. Myositis-specific autoantibodies: Their clinical and pathogenic significance in disease expression. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:607–12. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaji K, Fujimoto M, Hasegawa M, Kondo M, Saito Y, Komura K, et al. Identification of a novel autoantibody reactive with 155 and 140 kDa nuclear proteins in patients with dermatomyositis: An association with malignancy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:25–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chinoy H, Fertig N, Oddis CV, Ollier WE, Cooper RG. The diagnostic utility of myositis autoantibody testing for predicting the risk of cancer-associated myositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1345–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.068502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato S, Hirakata M, Kuwana M, Suwa A, Inada S, Mimori T, et al. Autoantibodies to a 140-kd polypeptide, CADM-140, in Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1571–6. doi: 10.1002/art.21023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiorentino D, Chung L, Zwerner J, Rosen A, Casciola-Rosen L. The mucocutaneous and systemic phenotype of dermatomyositis patients with antibodies to MDA5 (CADM-140): A retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Betteridge Z, Gunawardena H, North J, Slinn J, McHugh N. Identification of a novel autoantibody directed against small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme in dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3132–7. doi: 10.1002/art.22862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]