Abstract

Since robust osteogenic differentiation and mineralization are integral to the engineering of bone constructs, understanding the impact of the cellular microenvironments on human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSCs) osteogenic differentiation is crucial to optimize bioreactor strategy. Two perfusion flow conditions were utilized in order to understand the impact of the flow configuration on hMSC construct development during both pre-culture (PC) in growth media and its subsequent osteogenic induction (OI). The media in the in-house perfusion bioreactor was controlled to perfuse either around (termed parallel flow [PF]) the construct surfaces or penetrate through the construct (termed transverse flow [TF]) for 7 days of the PC followed by 7 days of the OI. The flow configuration during the PC not only changed growth kinetics but also influenced cell distribution and potency of osteogenic differentiation and mineralization during the subsequent OI. While shear stress resulted from the TF stimulated cell proliferation during PC, the convective removal of de novo extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and growth factors (GFs) reduced cell proliferation on OI. In contrast, the effective retention of de novo ECM proteins and GFs in the PC constructs under the PF maintained cell proliferation under the OI but resulted in localized cell aggregations, which influenced their osteogenic differentiation. The results revealed the contrasting roles of the convective flow as a mechanical stimulus, the redistribution of the cells and macromolecules in 3D constructs, and their divergent impacts on cellular events, leading to bone construct formation. The results suggest that the modulation of the flow configuration in the perfusion bioreactor is an effective strategy that regulates the construct properties and maximizes the functional outcome.

Introduction

Bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) have high replicative potential and are inducible osteoprogentors, making them the cells of choice in bone tissue engineering. MSCs are also a significant source of trophic factors and play important roles in the secretion and maintenance of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Combining hMSCs with 3D scaffolds is an important approach, because the scaffolds provide a structural template and environmental cues that direct MSC proliferation and osteogenic differentiation. The formation of such engineered bone constructs requires coordinated cell proliferation, osteogenic differentiation, and, ideally, maintenance of a progenitor pool in the constructs for bone turnover on implantation. Parallel to the efforts to develop biomimetic scaffolds, bioreactors play important roles in 3D construct development, because the flow configuration can modulate the spatial profiles of the regulatory macromolecules and provide mechanical stimuli that are inductive to bone construct formation.1,2 As such, bioreactors have been extensively applied in bone tissue regeneration.3–5 Recently, we have shown that flow configurations in the perfusion bioreactor system regulated the composition of the cellular microenvironment characterized by ECM proteins and growth factors (GFs), which subsequently influenced hMSC proliferation and maintenance of their multi-lineage potential.6 However, the role of such cellular microenvironments in hMSCs' responses to the osteogenic induction (OI) remains unknown. Since robust osteogenic differentiation and mineralization are integral to engineered bone constructs, understanding the impact of the cellular microenvironments on hMSC osteogenic differentiation is crucial in optimizing the bioreactor strategy for engineering bone constructs.

A commonly used approach for the in vitro MSC OI and mineralization is the addition of dexamethasone (Dex) and phosphate sources, such as sodium β-glycero-phosphate and ascorbic acid-2 phosphate.7,8 However, MSC osteogenic differentiation can also be induced or enhanced by ECM proteins such as collagen I (COL I) and vitronectin through extracellular signal-regulated kinase in the absence of chemical induction.9,10 The ECM microenvironments also play an important role in the late stage of osteogenic differentiation and mineralization.11 Mineralized ECM matrices incorporated into poly (ɛ-caprolactone) or titanium (Ti) scaffold modulated osteogenic differentiation, as evidenced in its ability to induce osteogenic differentiation of rat MSCs in the absence of Dex.12,13 In the presence of the chemical induction, cells cultured in a Ti/ECM scaffold further accelerated the osteogenic differentiation as compared with those in a plain Ti scaffold.12 Moreover, ECM proteins regulated hMSC osteogenic differentiation through their interactions with GFs, such as bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2). Both are endogenously secreted by hMSCs.14,15 BMP-2 is a potent inducer of hMSC osteogenic differentiation, whereas FGF-2 increases hMSC multipotentiality.16,17 The bioactivity of both GFs is influenced by their binding with ECM proteins, which can be significantly biased by the flow configuration in bioreactors.6,16,18 To date, the impact of the micro-environmental factors regulated by the flow configuration on hMSC osteogenic differentiation and mineralization in 3D constructs has not been fully understood. In particular, a few studies have reported the impact of de novo microenvironment on hMSC responses to osteoinductive stimuli, including osteoinductive media and shear stress, over the in vitro life span of the constructs. Understanding the role of de novo ECM microenvironment on hMSC proliferation and osteogenic differentiation has important implication in designing an optimal bioreactor strategy for bone construct tissue engineering.

Earlier, we reported that the flow configurations in the in-house perfusion bioreactor system modulated the spatial distribution of ECM proteins and GFs (e.g., FGF-2), influencing hMSC progenicity and their progression down the osteogenic lineage in the absence of chemical induction.6 In the current study, it is hypothesized that the accumulation and spatial distribution of the endogenous ECM and GFs in the constructs during the pre-culture (PC) influence hMSCs' response to osteogenic stimuli and construct mineralization. A staged bioreactor was operated with 7 days of the PC in the growth media followed by an additional 7 days of culture in the OI media under two different flow configurations. The results suggest a novel bioreactor operation strategy that maximizes the functional outcome of the engineered bone constructs from hMSCs.

Materials and Methods

hMSCs and polyethylene terephthalate scaffold preparation

Standardized frozen hMSCs were obtained from the Tulane Center for Gene Therapy and cultured following the method outlined in our previous publications.19,20 Briefly, hMSCs were expanded using minimum essential medium-alpha and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals) (growth media) in a standard CO2 incubator (37°C and 5% CO2). Cells from the same donor at passage 5 were seeded for each experiment, and cells from multiple donors were used in the experiments. All reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, and all antibodies were purchased from Abcam, unless otherwise noted.

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) matrices were treated as previously described.19,21 Briefly, commercial nonwoven PET fabrics were washed in de-ionized water, hydrolyzed with 1% (wt) NaOH, and thermally compressed to approximately 1.2 mm in thickness and 89% porosity. After treatment, the matrices were cut into circular disks with diameters of 1.6 cm and tucked into the chambers for the perfusion bioreactor culture described next. The average pore diameter of the PET scaffold as measured using a liquid extrusion method is approximately 70 μm.21

Bioreactor system setup and perfusion culture

The in-house perfusion bioreactor system developed and utilized in our previous studies6,19 was modified for this study. Briefly, four perfusion chambers were utilized with two PET matrices tucked in each of three grooves in each chamber. The bioreactor system also included a media container, three multi-channel peristaltic pumps, and a fresh media container stored in a refrigerator. The whole system, except for the pumps, was placed in a standard CO2 incubator at 37°C. There were three circulating loops in the system: a main circulating loop, an inoculation loop, and a fresh media replenishing loop. The two inlets in each chamber were connected to individual inlets from a computerized precise peristaltic pump (Cole-Parmer) that has eight individual channels. During the operation, media were drawn from the media reservoir, pumped through the compartments, merged at the outlets of the chambers, and returned to the media reservoir. Using the seeding loop, 2.0×106 cells were seeded in each chamber at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min as previously described.20 After seeding, the main circulating loop was switched on as soon as the inoculation loop was closed. Under the flow rate used, shear stress at the surfaces of the parallel flow (PF) constructs was estimated to be less than 1×10−5 Pa,20 whereas the average wall stress as a result of interstitial flow in the transverse flow (TF) constructs is estimated to be 5.5×10−4 Pa.6

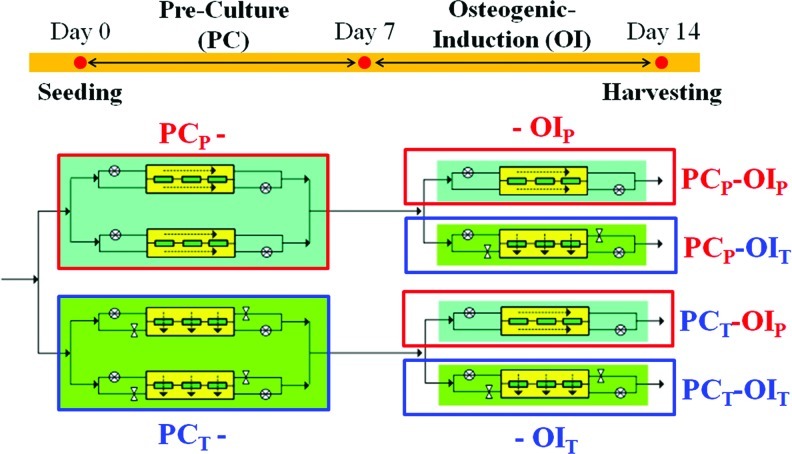

For the staged bioreactor operation, two chambers were operated under the PF, and the other two chambers were operated under the TF for a period of 7 days with growth media (Fig. 1). For the PF, media were perfused at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min that was evenly divided between the two sides of each chamber. For the TF, the bottom inlet and top outlet of the chambers were closed, and the media were forced to transversely penetrate the matrices in each chamber at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. After 7 days of the PC, the flow configuration in one of the two chambers with the identical flow configuration during the PC was switched (i.e., PF to TF or TF to PF), while the other one remained under the same flow configuration for an additional 7 days in OI media, which consisted of Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals), 100 nM Dex, 10 mM sodium-β-glycerophosphate, and 12.8 mg/L ascorbic acid-2 phosphate. At day 14, the constructs were aseptically removed from the bioreactor chambers and termed the PCP-OIP, PCP-OIT, PCT-OIP, or PCT-OIT constructs, in which the subscripts represent the flow configurations of the PF (P) or TF (T) during the respective culture period (Fig. 1). The media in the reservoir were changed before lactate concentration reached 0.45 g/mL. At least triplicate bioreactor experiments were performed for cell growth; alkaline phosphatase (ALP), calcium deposition, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), quantitative polymerase chain reaction measurement, and representative results are presented.

FIG. 1.

Schematics of the staged bioreactor operation. The in-house perfusion bioreactor has four chambers, with two chambers operated under the PF and the other two under the TF for 7 days of the PC in growth media. After the PC, the flow configuration in one of the two chambers of the identical PC flow configuration was switched, and the entire bioreactor system was operated for an additional 7 days with OI media. After 14 days of the culture, the constructs are termed PCP-OIP, PCP-OIT, PCT-OIP, or PCT-OIT, in which the subscripts represent the flow configurations of the parallel (P) (Red font) or transverse (T) flow (Blue font) during the two culture periods. PF, parallel flow; TF, transverse flow; PC, pre-culture; OI, osteogenic induction. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

DNA assays

Cell numbers in the PET matrices were determined by DNA assay following a method reported in one of our previous publications.19 Briefly, constructs were lysed using the Tris-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid -Triton-X 100 solution with proteinase K at 50°C overnight. Picogreen (Molecular Probes) was added to triplicate samples and a series of DNA standards in a 96-well plate, which was then incubated and read using Fluoro Count (PerkinElmer). hMSCs were found to contain an average DNA of 9.3 pg/cell. For cell numbers, triplicate matrices from each chamber were used for each data point, and three independent runs were repeated under identical operation conditions.

ALP activity and calcium deposition

ALP was determined by a spectrophotometric endpoint assay following the method reported in our previous publication.22 The constructs from the bioreactor were incubated with a lysing buffer (phosphate buffered saline [PBS] with 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodiumdodecylsulfate, 0.1 mg/mL phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, and 3% aprotinin) for 1 h. The para-nitrophenolphosphate (PNPP) substrate was then added to cell lysates. After incubation at 37°C for 45 min, the reaction was stopped using PBS with 0.5 N NaOH. A series of para-nitrophenol standards were used to construct a standard curve. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm, and the background absorbance measured at 655 nm was subtracted. For the calcium deposition, the constructs from the perfusion chamber were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and stained with Alizarin Red S. After washing with deionized water, calcium was desorbed in 10% cetylpyridinium chloride. The absorbance was spectrophotometrically measured at a wavelength of 540 nm.

Histological evaluation

hMSCs/PET constructs were prepared for histological observation after 14 days of the staged bioreactor operation. The samples were fixed in 4% PFA, and standard dehydration in sequentially increasing ethanol solutions up to 100% ethanol was performed, followed by immersion in xylene, paraffin-saturated xylene, and, finally, molten paraffin. Tissue blocks were sectioned at 40 μm and stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for visualization of cell distribution and Alizarin Red S staining for calcium distribution.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ECM proteins were quantified by in-situ ELISA following a method outlined in one of our previous publications.23 Briefly, the constructs removed from the chambers were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 1 h. After PBS wash, the samples were permeablized by washing with 0.2–0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS twice and then incubated with blocking buffer, 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS, for 30 min. Samples were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C, washed with blocking buffer, and incubated with an ALP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking buffer wash, 1 mL PNPP substrate was added to each sample and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. After the addition of 0.5 N NaOH stop solution, the absorbance was spectrophotometrically measured at a wavelength of 405 nm, and background absorbance at 655 nm was subtracted. ELISA measurements were then normalized to β-actin and plotted.

Real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated using the Rneasy Plus kit (Qiagen) from constructs in each condition, and analyzed following an established method in our laboratory.24 Reverse transcription was carried out using 2 pg of total RNA, anchored oligo-dT primers (Operon) and Superscript III (Invitrogen). Primers specific for target genes were designed using the software Oligo Explorer 1.2 (Genelink), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an endogenous control for normalization (Table 1). Real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) reactions were performed on an ABI7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems), using SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix. The amplification reactions were performed, and the quality and primer specificity were verified. Average PCR efficiencies were calculated using the software LinRegPCR,25 based on duplicated amplifications of eight independent cDNAs for all the genes analyzed. Reaction efficiencies varied from 97.1% to 102.5%. Even though a slight deviation from 100% was detected, the efficiencies were not considered in our calculations of relative transcript levels, because we would have to assume constant efficiency throughout the reaction. Fold variation in gene expressions were quantified using the comparative Ct method: 2−(CtTreatment−CtControl), which is based on the comparison of the expression of the target gene (normalized to GAPDH) over a 14-day culture period.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Used for Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction and NCBI PrimerBank Accession Numbers

| |

Primer sequence |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Forward | Reverse | Accessionnumber |

| BMP-2 | 5′-TTCCCCGTGACCAGACTTTTGG-3′ | 5′-GCCACTTCCACCACGAATCCAT-3′ | NM_001200 |

| RUNX2 | 5′-CCAACCCACGAATGCACTATC-3′ | 5′-TAGTGAGTGGTGGCGGACATAC-3′ | NM_001015051 |

| OSX | 5′-CTGGCACACAGGCGAGAGGC-3′ | 5′-GGAGCAGAGCAGGCAGGTGAAC-3′ | AF477981 |

| OP | 5′-AGCGGAAAGCCAATGATGAGAGC-3′ | 5′-ACTTTTGGGGTCTACAACCAGCAT-3′ | NM_001040058 |

| OC | 5′-GGCAGCGAGGTAGTGAAGAGAC-3′ | 5′-GAAAGCCGATGTGGTCAGCCAA-3′ | NM_199173 |

| GAPDH | 5′-ATG-GGG-AAG-GTG-AAGGTCGG-3′ | 5′-GGA-GTG-GGT-GTC-GCT-GTT-GAA-3′ | NM_002046 |

BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; RUNX, runt-related transcription factor; OSX, osterix; OP, osteopontin; OC, osteocalcin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Statistics/data analysis

For a statistical comparison, a minimum of three scaffolds from each condition were used for each cellular test. For each condition, representative results from at least triplicate bioreactor experiments are reported. All data points are an average of at least three replicates and expressed as means±standard deviation of the means of samples. Statistical comparisons were performed by analysis of variance for multiple comparisons, and statistical significance was accepted at p<0.05.

Results

Cell proliferation during the OI

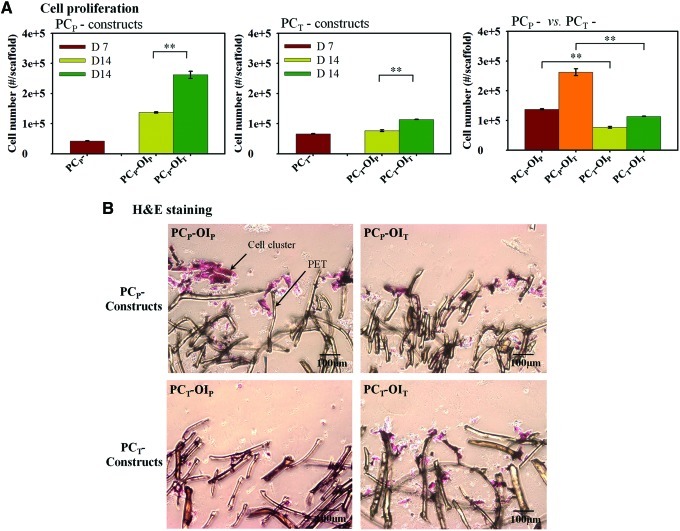

After 7 days of the PC in growth media, cells under the TF proliferated more rapidly with 1.5 times higher cell numbers compared with those under the PF, consistent with our previous results (Fig. 2). After switching to OI media, the TF accelerated cell growth in the PCP constructs, resulting in 1.9 times higher cell number in the PCP-OIT constructs compared with those in the PCP-OIP constructs at day 14 (Fig. 2). Similar trends were observed for the PCT constructs with 1.5 times higher cell number in the PCT-OIT constructs than those in the PCTOIP constructs by the end of the OI at day 14 (Fig. 2). However, under the same OI flow condition, the PCP constructs had higher cell proliferation compared with their PCT counterparts with 1.8 and 2.3 times higher cell numbers at day 14 (i.e., PCP-OIP vs. PCT-OIP and PCP-OIT vs. PCT-OIT), respectively. H&E staining revealed cell aggregation in the periphery of the PCP-OIP constructs, in contrast to the even cell distribution in the PCT-OIT constructs. The PCT constructs also have lower cellularity compared with their PCP counterparts (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

hMSC proliferation and histological staining. (A) Cell proliferation. The OI under the TF enhanced cell proliferation, but the increases in the PCT constructs were modest. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). (B) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of histological sections of the constructs after 14 days of the staged reactor operation. Cell aggregates were found in the periphery of the PCP-OIP constructs, in contrast to the even cell distribution in the PCT-OIT constructs. The scale was 100 μm in length in all cases. Magnification: 100×. hMSC, human mesenchymal stem cell. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

ALP activity and calcium deposition

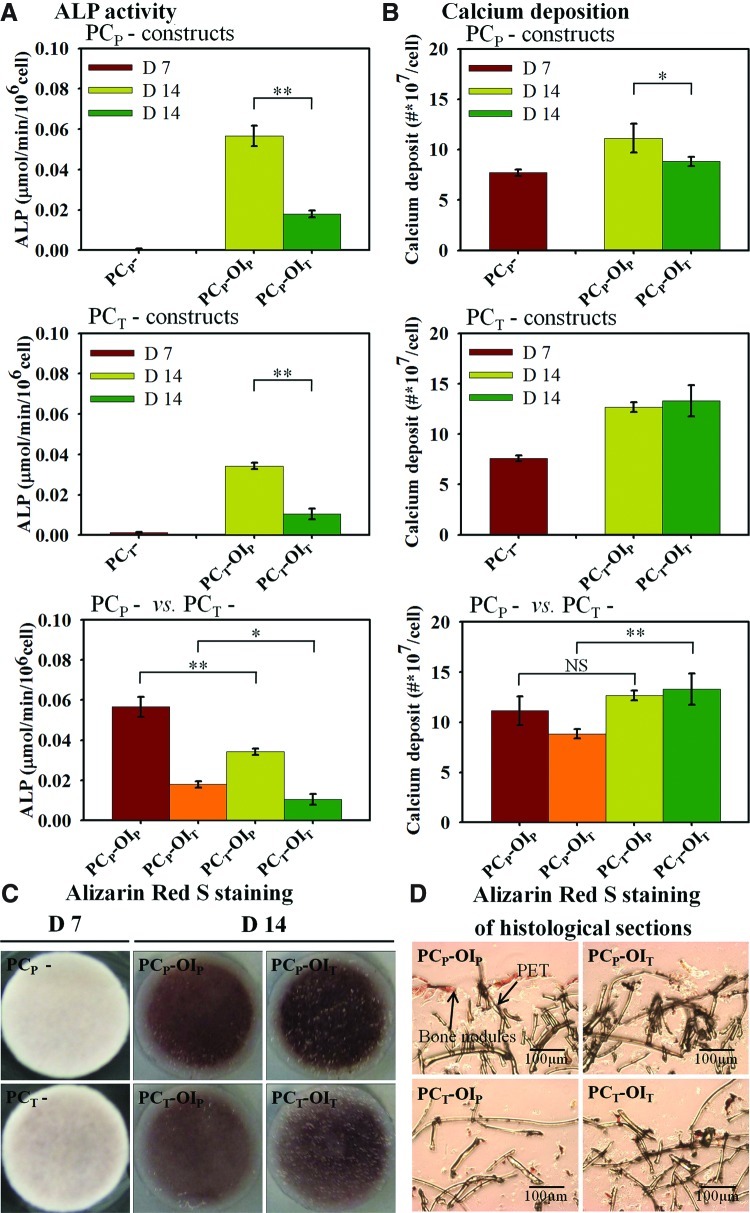

After 7 days of the PC in growth media, the level of ALP activity under the TF was 2.2 times higher than that under the PF, consistent with our previous results (Fig. 3A). After the additional 7 days of the OI, the PCP-OIP constructs had about 3.1 times higher ALP activity than that in the PCP-OIT constructs. Similarly, the ALP level in the PCT-OIP constructs was 3.3 times higher than that in the PCT-OIT constructs at day 14. However, ALP activities of the PCP constructs appeared to have increased more significantly than those of the PCT constructs after the OI (i.e., PCP-OIP vs. PCT-OIP and PCP-OIT vs. PCT-OIT constructs) at day 14. For the calcium deposition at day 7, the levels in both PCP and PCT constructs were comparable (Fig. 3B). At day 14 after 7 days of the OI, calcium deposition in the PCP-OIP constructs was approximately 1.26 times higher than that in the PCP-OIT constructs, while they were comparable in the PCT constructs under both flow configurations. The TF in the PCT constructs during the PC also appeared to potentiate calcium deposition with higher calcium depositions in the PCT constructs compared with their PCP counterparts with a statistically significant difference between the PCP-OIT constructs and the PCT-OIT constructs (Fig. 3B). While the PCP-OIT constructs appeared to have the highest calcium staining on the surface (Fig. 3C), Alizarin Red S staining of the histological slices indicates a more even distribution of calcium nodule in the PCT constructs compared with those of the PCP constructs, where calcium nodules were mainly found on the periphery of the constructs (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

hMSC osteogenic differentiation under two flow configurations. (A) The OI under the PF resulted in higher ALP expression as compared with those induced under the TF. A similar trend was observed in the PCT constructs, but the overall increases were lower compared with the PCP constructs. (B) Calcium deposition in the PCP-OIP constructs was significantly higher than that of the PCP-OIT constructs, while there was no significant difference between two flow configurations in the PCT constructs. PCT constructs also have higher calcium depositions compared with their PCP counterparts with statistically significant differences between the PCT-OIT and PCP-OIT constructs. (C) Alizarin Red S staining of the constructs at days 7 and 14. Significant calcium increases in construct surfaces were observed in all constructs with the most intensive expression in the PCP-OIT constructs. (D) Alizarin Red S staining of the histological sections of the constructs after 14 days of the staged bioreactor culture revealed the localized calcium nodules in the PCP constructs. Magnification: 100×. Values are means±SD for three samples of each condition (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). ALP, alkaline phosphatase; SD, standard deviation; NS, no significance. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

ECM proteins and matrix-bound BMP-2

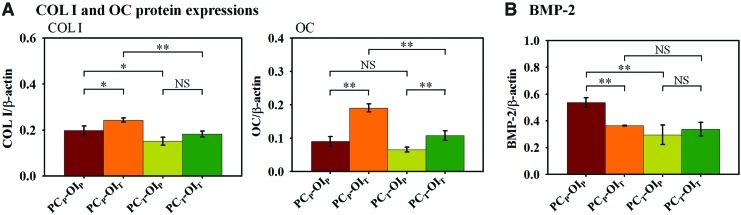

The expressions of ECM proteins and BMP-2 were normalized to β-actin as an endogenous control at day 14 (Fig. 4). The TF during the OI appeared to enhance COL I expressions, resulting in higher COL I expressions in the OIT constructs with a statistically significant difference between the PCP-OIP and the PCP-OIT constructs (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, the PC under the PF appeared to potentiate the COL I secretion during the OI from day 7 to 14, resulting in higher COL I expressions in the PCP-OIP and PCP-OIT constructs compared with those in the PCT-OIP and PCT-OIT constructs, respectively. For osteocalcin (OC) expression, the TF in the OI constructs appeared to enhance OC expression, with approximately 2.1 times and 1.6 times higher OC expression in the PCP-OIT and PCT-OIT constructs compared with those in the PCP-OIP and PCT-OIP constructs, respectively (Fig. 4A). The PC under the PF also appeared to potentiate OC depositions during the subsequent OI from day 7 to 14, resulting in 37% and 77% higher OC depositions in the PCP-OIP versus PCT-OIP constructs and the PCP-OIT versus PCT-OIT constructs, respectively, although the difference between PCP-OIP and PCT-OIP constructs was not statistically significant. For matrix-bound BMP-2, the highest expression was found in the PCP-OIP constructs after the OI at day 14, but remained comparable in other constructs (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Expression of extracellular and bone marker proteins. (A) COL I and OC protein expressions at day 14. The OI under the TF (e.g., OIT) enhanced COL I expression with the PCP-OIT constructs having the highest expression. Similar enhancement of OC expression by the transverse induction was observed for both PCP and PCT constructs. (B) Matrix-bound BMP-2. Matrix-bound BMP-2 in the PCP-OIP constructs was higher than that in the PCP-OIT constructs, while they were comparable in both flow conditions in the PCT constructs. Values are means±SD for three samples of each condition (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). COL I, collagen I; OC, osteocalcin; BMP, bone morphogenic protein; NS, no significance. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

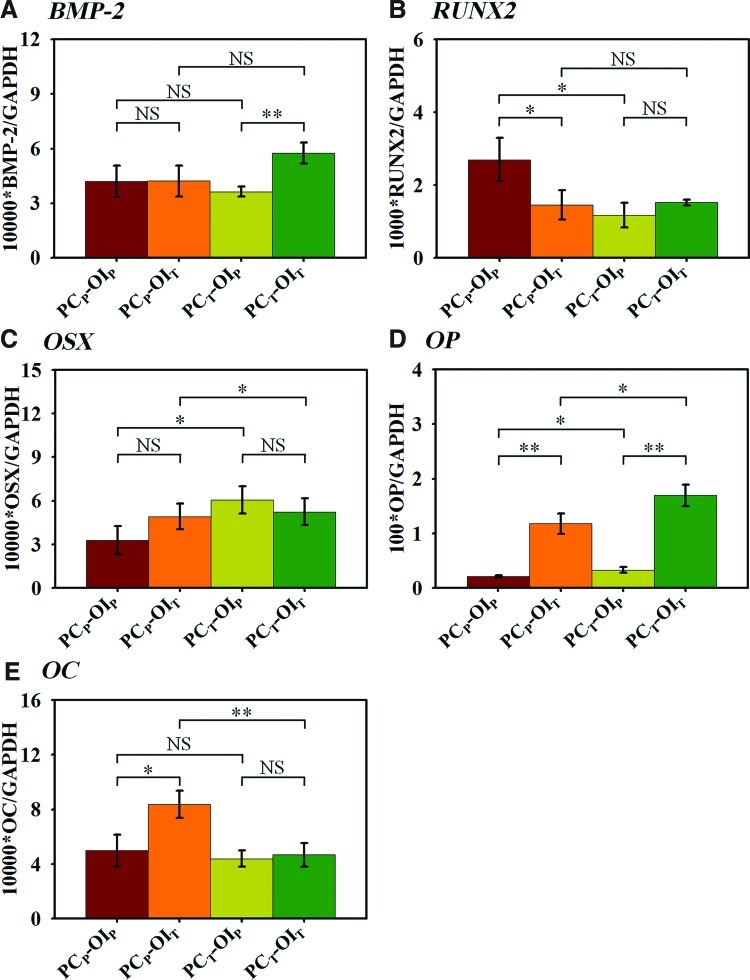

Osteogenic gene expressions

The expressions of the genes of interest at day 14 were normalized to the endogenous control (GAPDH) (Fig. 5). The highest BMP-2 expression was found in the PCT-OIT constructs with an approximately 1.6 times higher expression compared with the other conditions (Fig. 5A). The highest RUNX2 expression was found in the PCP-OIP constructs, which was approximately 1.8 times higher than those in the other constructs (Fig. 5B). In contrast to RUNX2 expression, OSX expression in the PCP-OIP constructs was the lowest among all conditions, while the highest OSX expression was observed in the PCT-OIP constructs (Fig. 5C). Osteopontin (OP) expression appeared to be enhanced by the TF during the OI, resulting in approximately 5.5 times and 5.1 times higher OP expressions in the PCP-OIT and PCT-OIT constructs than those in the PCP-OIP and PCT-OIP constructs at day 14, respectively (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, the constructs pre-cultured under the TF also enhanced OP expression during the OI from day 7 to 14, resulting in higher OP expressions in the PCT-OIP and PCT-OIT constructs compared with those in the PCP-OIP and PCP-OIT constructs. OC expression in the PCP-OIT constructs was approximately 1.7 times higher at day 14 than those in the PCP-OIP constructs, while OC expressions in the PCT constructs remained comparable under both flow conditions (Fig. 5E). Table 2 was a summary of the cellular properties of the constructs after the PC and the OI under two flow configurations.

FIG. 5.

Real time polymerase chain reaction of the bone marker genes normalized to GAPDH at day 14. (A) BMP-2 expression is the highest in the PCT-OIT constructs among all conditions. (B) RUNX2 expression is the highest in the PCP-OIP constructs among all conditions. (C) The PCT-OIP constructs had the highest OSX expression, whereas the PCP-OIP constructs had the lowest expression. (D) OP expression in the PCT constructs was higher than that in their PCP counterparts with the PCT-OIT constructs having the highest OP expression. (E) The PCP-OIT constructs had the highest OC expression, while the other three constructs had a comparable expression. Values are means±SD for three samples of each condition (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; RUNX, runt-related transcription factor; OSX, osterix; OP, osteopontin; OC, osteocalcin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NS, no significance. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Table 2.

Summary of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Construct Properties After the Pre-Culture and the Osteogenic Induction Under Two Flow Configurations

| |

|

|

|

Osteogenic induction at day 14 |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pre-culture at day 7 |

|

|

Bone marker proteins and calcium |

Bone marker genes |

|||||||||||

| Construct | Growth | ECMa | FGF-2a | Construct | Growth | COL I | OC | BMP-2 | ALP | CA2+ | BMP-2 | RUNX2 | OSX | OP | OC |

| PCP | + | ++ | +++ | OIP | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | + | + | + |

| OIT | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ||||

| PCT | ++ | + | + | OIP | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | ++ | + | + |

| OIT | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | ||||

+, ++, and +++ represent expression ranging from detectable to very high.

Reported in our previous study.6

ECM, extracellular matrix; FGF-2, fibroblast growth factor-2; PC, pre-culture; OI, osteogenic induction.

Discussion

Bioreactor fabrication strategy of bone constructs

Osteogenic differentiation is a process modulated by a cascade of gene expressions initially supporting proliferation and then the sequential cellular events related to the biosynthesis, organization, and mineralization of the bone ECM.26 In vivo, the ECM secretion is a critical step of osteogenic differentiation, and it is important in the maintenance of bone tissue.11 ECM proteins not only provide the binding sites for GFs, including FGF-2 and BMP-2,16,18,27 but they also facilitate the calcification process by providing nucleation sites for the apatite formation on collagen fibers and on calcium binding of noncollagenous proteins.11 As such, decellularized ECM matrices alone or incorporated in the scaffolds have been used to promote MSC osteogenic differentiation.12,28 In a recent study, pre-cultivation of hMSCs in growth media followed by the OI maximized the ECM mineralization in silk fibroin scaffolds, although the exact role of the ECM microenvironment remained unknown.29 While these studies highlighted the influence of the ECM microenvironment on hMSC osteogenic differentiation, the role of the de novo ECM microenvironment has not been fully understood and the control of microenvironment formation has not been effectively implemented in the perfusion bioreactors.

Impact of the PC on hMSC proliferation in OI media

While cell proliferation is an important step in populating the 3D scaffolds, hMSC proliferation could occur at the expense of their differentiation potency, compromising construct properties. Thus, bioreactor operating conditions that promote cell proliferation as well as maintain their differentiation potency are central in bone regeneration. While Dex is known to inhibit hMSC proliferation in general,7 hMSC proliferation in OI media can still be enhanced by shear stress stimulation.30 Indeed, after switching to OI media at day 7, cell proliferation remained higher in the constructs under the TF (i.e., PCP-OIT>PCP-OIP and PCT-OIT>PCT-OIP). However, the overall levels of cell proliferation in the PCT constructs were lower than those in the PCP constructs, suggesting the diminished proliferation potential after the PC under the TF. The PC under the PF has been shown to be more effective in preserving ECM proteins and GFs (e.g., FGF-2), which may play a role in enhancing cell growth in the subsequent culture in OI media. In contrast, the removal of ECM proteins and GFs in the PCT constructs may compromise their proliferation potential, resulting in decreased cell proliferation during the subsequent OI. Together, the results suggest that the PC in growth media not only influences their growth kinetics but also affects their proliferation potential during the OI.

Impact of the PC and the flow configuration on hMSC osteogenic differentiation

The progression of hMSC osteogenic differentiation was measured by a combination of early- and late-stage osteogenic markers. Higher shear stress in the TF decreased ALP expressions during the OI in both the PCP and the PCT constructs (i.e., PCP-OIT<PCP-OIP and PCT-OIT<PCT-OIP). However, under the identical OI condition, the higher ALP expression in the PCP constructs compared with their PCT counterparts suggests that the close cell–cell contacts and localized 3D cell confluence in the PCP constructs enhanced the ALP expression in the subsequent OI. ALP expression increases at the early stage of osteogenic differentiation and then declines as hMSCs become mature osteoblasts. Some authors have reported a peak of ALP activity in 3D cultured osteo-progenitor cells after 2 weeks,1,31 while others reported a decrease in ALP activity after 7 days of the culture on the OI.32 Thus, the temporal profiles of ALP expression alone may not be a precise indication of the extent of osteogenic differentiation.

The higher calcium content in the PCP-OIP constructs at day 14 compared with those in the PCP-OIT constructs suggests that the close cell-ECM contacts and localized 3D cell confluence are more potent in enhancing calcium deposition than stimulation by the TF. A similar observation has been reported in previous studies in which localized cell aggregation and close contact with ECM enhanced hMSC calcium deposition.12,33,34 However, for the PCT constructs with an even cell distribution from the PC, calcium depositions in both flow configurations were comparable and were higher than their PCP counterparts. For the PCT constructs, the short duration of the OI (e.g., 7 days) compared with what was used in other studies (>14 days) could be a contributing factor that resulted in the limited difference between the PCT-OIT and PCT-OIP constructs.12,34 It is noted, however, that the spatial distribution of calcium nodule was significantly improved in the PCT constructs, supporting the notion that the dynamic flow not only enhanced calcium deposition but also improved their spatial distribution.34–36 In addition to ECM proteins, matrix-bound FGF-2 in the PCP constructs was found to be four times higher than those in the PCT constructs after 7 days of the PC in growth media.6 Autocrine FGF-2 is known to promote hMSC proliferation and increase their multi-potentiality.37 Thus, the higher level of FGF-2 in the PCP constructs may also play a role in potentiating hMSC osteogenic differentiation in tandem to ECM proteins. The exact contribution of ECM proteins and endogenous GFs such as FGF-2 requires further study.

The production of COL I is one of the earliest events in hMSC osteogenic differentiation, and its interaction with integrin alpha 2 is required for the osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells.16 In addition, collagenous proteins provide surfaces for the nucleation of the apatite and are essential in bone construct calcification.11 The TF during the OI enhanced Col I secretion (i.e., PCP-OIT>PCP-OPP, and PCT-OIT>PCT-OIP), presumably due to shear stress stimulation. This is in agreement with previous studies that demonstrated the enhancement of Col I secretion by shear stress in a spinner flask during the OI compared with that in the static culture.38 However, the higher Col I expression was also observed in the PCP constructs compared with their PCT counterparts (i.e., PCP-OIP>PCT-OIP and PCP-OIT>PCT-OIT) at day 14, suggesting that the PC impact Col I secretion during the OI. Thus, the higher retention of the ECM and GFs in the PCP constructs may have self-perpetuating effects and promote COL I expression during the subsequent OI, as previously reported.34 In addition to COL I, OC is synthesized only by mature osteoblasts, and it binds collagen and calcium in the ECM of bone tissue.39 Elevated OC levels in the OIT constructs compared with their OIP counterparts at day 14 confirmed shear stress enhancement of the construct mineralization. Furthermore, the highest OC expression in the PCP-OIT constructs suggests the synergistic enhancement of OC expression as a result of ECM retention during the PC and shear stress stimulation during the OI. Together, the results suggest that the extent of osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of 3D constructs from hMSCs is influenced by the combined perfusion conditions in both the PC and the OI.

Expressions of bone marker genes revealed the temporal patterns of hMSC osteogenic commitment influenced by the perfusion conditions during both the PC and the OI. The highest BMP-2 expression in the PCT-OIT constructs was likely a result of continued exposure to the TF, as previously reported.34 Generally, RUNX2 and OSX are known as master switches of hMSC osteoblastic differentiation, whereas OC and OP are expressed later in the differentiation process.40,41 RUNX2 is a transcription factor for osteogenic differentiation, but it is down-regulated as MSCs mature.42 In the current study, RUNX2 expression was only up-regulated in the PCP-OIP constructs at day 14, suggesting that cells in the three other conditions were in advanced stages of bone maturation. This observation was further supported by the opposing trend of OSX expression, where the PCP-OIP constructs had the lowest expression among all conditions. OSX is downstream of RUNX2, and its expression is required for the pre-osteoblast differentiation into functional osteoblasts expressing high levels of osteoblast marker genes.43

The shear stress enhancement of osteogenic differentiation in the constructs under the TF was further supported by the profiles of OP and OC gene expressions. OP is a late-stage osteogenic marker gene that can be readily induced by the fluid flow.44 It should be noted that OP peaks twice, once during proliferation and then again at the onset of mineralization.45 Earlier, we only observed the first peak when hMSCs were cultured in growth media for 14 days.6 In the current study, however, the significantly higher levels of OP expressions in the OIT constructs (i.e., PCP-OIT>PCP-OIP and PCT-OIT>PCT-OIP) at day 14 coincide with the enhanced matrix mineralization (Fig. 3B), suggesting the fully differentiated hMSCs. The level of OC expression, another late-stage bone marker, also significantly increased in the PCP constructs induced under the TF. Taken together, the results indicated that hMSC osteogenic differentiation and mineralization were synergistically enhanced by the ECM accumulation during the PC and the subsequent shear stress stimulation during the OI.

Nonwoven PET scaffolds have excellent chemical and mechanical stability and have been used as scaffolds that support both embryonic and adult stem cells.22,46 As an in vitro model, PET's inert chemical properties and low affinity to the ECM proteins and GFs allow an investigation of the role of the de novo ECM microenvironment without potential interference resulting from scaffold degradation and/or selective affinity to the specific protein components. Indeed, studies have shown that scaffold structural stability and cell–scaffold interactions significantly influence hMSC proliferation and osteogenic differentiation in 3D scaffolds in response to shear stress stimulation.1,47 It is noted, however, that the biomimetic scaffolds commonly used in bone regeneration have strong interactions with cell or regulatory macromolecules, which could significantly bias the distribution of ECM proteins and complicate the interpretation of the influence of flow configuration. Nonetheless, the results of the current study highlight the role of the flow configuration as an independent factor in directing the cellular events of hMSC proliferation, ECM secretion, and osteogenic differentiation and mineralization in 3D constructs. The results demonstrate that the modulation of the flow configuration in the perfusion bioreactor is an effective strategy that regulates the construct properties and maximizes the functional outcome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by DOD Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program grant (W81XWH-07-1-0363) to T.M. The authors would like to thank Dr. Brian Washburn of the Molecular Cloning Facility at the FSU Department of Biological Science for his technical assistance in real-time PCR analysis.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Meinel L. Karageorgiou V. Fajardo R. Snyder B. Shinde-Patil V. Zichner L. Kaplan D. Langer R. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Bone tissue engineering using human mesenchymal stem cells: effects of scaffold material and medium flow. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:112. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000007796.48329.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burdick J.A. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Engineered microenvironments for controlled stem cell differentiation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:205. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCoy R.J. O'Brien F.J. Influence of shear stress in perfusion bioreactor cultures for the development of three-dimensional bone tissue constructs. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16:587. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2010.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salter E. Goh B. Hung B. Hutton D. Ghone N. Grayson W.L. Bone tissue engineering bioreactors—a role in the clinic? Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18:62. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2011.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeatts A.B. Fisher J.P. Bone tissue engineering bioreactors: dynamic culture and the influence of shear stress. Bone. 2011;48:171. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J. Ma T. Perfusion regulation of hMSC microenvironment and osteogenic differentiation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:252. doi: 10.1002/bit.23290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng S.L. Yang J.W. Rifas L. Zhang S.F. Avioli L.V. Differentiation of human bone marrow osteogenic stromal cells in vitro: induction of the osteoblast phenotype by dexamethasone. Endocrinology. 1994;134:277. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.1.8275945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alves N.M. Leonor I.B. Azevedo H.S. Reis R.L. Mano J.F. Designing biomaterials based on biomineralization of bone. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:2911. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salasznyk R.M. Klees R.F. Hughlock M.K. Plopper G.E. ERK signaling pathways regulate the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on collagen I and vitronectin. Cell Commun Adhes. 2004;11:137. doi: 10.1080/15419060500242836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kundu A.K. Putnam A.J. Vitronectin and collagen I differentially regulate osteogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:347. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beniash E. Biominerals-hierarchical nanocomposites: the example of bone. Nanomed and Nanobiotechnol. 2011;3:47. doi: 10.1002/wnan.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datta N. Pham Q.P. Sharma U. Sikavitsas V.I. Jansen J.A. Mikos A.G. In vitro generated extracellular matrix and fluid shear stress synergistically enhance 3D osteoblastic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505661103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao J.H. Guo X.A. Nelson D. Kasper F.K. Mikos A.G. Modulation of osteogenic properties of biodegradable polymer/extracellular matrix scaffolds generated with a flow perfusion bioreactor. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2386. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ducy P. Zhang R. Geoffroy V. Ridall A.L. Karsenty G. Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell. 1997;89:747. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seib F.P. Franke M. Jing D. Werner C. Bornhäuser M. Endogenous bone morphogenetic proteins in human bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2009;88:257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzawa M. Takeuchi Y. Fukumoto S. Kato S. Ueno N. Miyazono K. Matsumoto T. Fujita T. Extracellular matrix-associated bone morphogenetic proteins are essential for differentiation of murine osteoblastic cells in vitro. Endocrinology. 1999;140:2125. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.5.6704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao G. Gopalakrishnan R. Jiang D. Reith E. Benson M.D. Franceschi R.T. Bone morphogenetic proteins, extracellular matrix, and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways are required for osteoblast-specific gene expression and differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:101. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seib F.P. Lanfer B. Bornhäuser M. Werner C. Biological activity of extracellular matrix-associated BMP-2. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2010;4:324. doi: 10.1002/term.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao F. Ma T. Perfusion bioreactor system for human mesenchymal stem cell tissue engineering: dynamic cell seeding and construct development. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;91:482. doi: 10.1002/bit.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao F. Chella R. Ma T. Effects of shear stress on 3-D human mesenchymal stem cell construct development in a versatile perfusion bioreactor system: experiments and hydrodynamic modeling. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;96:584. doi: 10.1002/bit.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y. Ma T. Yang S.T. Kniss D.A. Thermal compression and characterization of three-dimensional nonwoven PET matrices as tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2001;22:609. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grayson W.L. Ma T. Bunnell B. Human mesenchymal stem cell tissue development in 3D PET matrices. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:905. doi: 10.1021/bp034296z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sellgren K.L. Ma T. Perfusion conditioning of hydroxyapatite-chitosan-gelatin scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration from human mesenchymal stem cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012;6:49. doi: 10.1002/term.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao F. Grayson W.L. Ma T. Irsigler A. Perfusion affects the tissue developmental patterns of human mesenchymal stem cells in 3D scaffolds. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:421. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramakers C. Ruijter J.M. Deprez R.H. Moorman A.F. Assumption-free analysis of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) data. Neurosci Lett. 2003;339:62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein G.S. Lian J.B. Stein J.L. van Wijnen A.J. Montecino M. Transcriptional control of osteoblast growth and differentiation. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:593. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoshiba T. Lu H.X. Kawazoe N. Chen G.P. Decellularized matrices for tissue engineering. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:1717. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2010.534079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen X.D. Dusevich V. Feng J.Q. Manolagas S.C. Jilka R.L. Extracellular matrix made by bone marrow cells facilitates expansion of marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells and prevents their differentiation into osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1943. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thimm B.W. Wüst S. Hofmann S. Hagenmüller H. Müller R. Initial cell pre-cultivation can maximize ECM mineralization by human mesenchymal stem cells on silk fibroin scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2218. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li D. Tang T. Lu J. Dai K. Effects of flow shear stress and mass transport on the construction of a large-scale tissue-engineered bone in a perfusion bioreactor. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2773. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2008.0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sikavitsas V.I. Bancroft G.N. Mikos A,G. Formation of three-dimensional cell/polymer constructs for bone tissue engineering in a spinner flask and a rotating wall vessel bioreactor. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62:136. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stiehler M. Bunger C. Gaatrup A. Lund M. Kassem M. Mygind T. Effect of dynamic 3-D culture on proliferation, distribution, and osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;89:96. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kundu A.K. Khatiwala C.B. Putnam A.J. Extracellular matrix remodeling, integrin expression, and downstream signaling pathways influence the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells on poly(lactide-co-glycolide) substrates. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:273. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bjerre L. Bunger C.E. Kassem M. Mygind T. Flow perfusion culture of human mesenchymal stem cells on silicate-substituted tricalcium phosphate scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2616. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomes M.E. Sikavitsas V.I. Behravesh E. Reis R.L. Mikos A.G. Effect of flow perfusion on the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells cultured on starch-based three-dimensional scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;67:87. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holtorf H.L. Sheffield T.L. Ambrose C.G. Jansen J.A. Mikos A.G. Flow perfusion culture of marrow stromal cells seeded on porous biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:1238. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-5536-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rider D.A. Dombrowski C. Sawyer A.A. Ng G.H.B. Leong D. Hutmacher D.W. Nurcombe V. Cool S.M. Autocrine fibroblast growth factor 2 increases the multipotentiality of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1598. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang T.W. Wu H.C. Wang H.Y. Lin F.H. Sun J.S. Regulation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells into osteogenic and chondrogenic lineages by different bioreactor systems. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;88:935. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Q.H. Cen L. Zhou H. Yin S. Liu G.P. Liu W. Cao Y.L. Cui L. The role of the extracellular signal-related kinase signaling pathway in osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells and in adipogenic transition initiated by dexamethasone. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3487. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu J.X. Sasano Y. Takahashi I. Mizoguchi I. Kagayama M. Temporal and spatial gene expression of major bone extracellular matrix molecules during embryonic mandibular osteogenesis in rats. Histochem J. 2001;33:25. doi: 10.1023/a:1017587712914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arnsdorf E.J. Tummala P. Kwon R.Y. Jacobs C.R. Mechanically induced osteogenic differentiation-the role of RhoA, ROCKII and cytoskeletal dynamics. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:546. doi: 10.1242/jcs.036293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komori T. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by transcription factors. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:1233. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakashima K. Zhou X. Kunkel G. Zhang Z. Deng J.M. Behringer R.R. Crombrugghe B.D. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2002;108:17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braccini A. Wendt D. Jaquiery C. Jakob M. Heberer M. Kenins L. Wodnar-Filipowicz A. Quarto R. Martin I. Three-dimensional perfusion culture of human bone marrow cells and generation of osteoinductive grafts. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1066. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein G.S. Lian J.B. van Wijnen A.J. Stein J.L. Montecino M. Javed A. Zaidi S.K. Young D.W. Choi J.Y. Pockwinse S.M. Runx2 control of organization, assembly and activity of the regulatory machinery for skeletal gene expression. Oncogene. 2004;23:4315. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ouyang A. Ng R. Yang S.T. Long-term culturing of undifferentiated embryonic stem cells in conditioned media and three-dimensional fibrous matrices without extracellular matrix coating. Stem Cells. 2007;25:447. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bjerre L. Bunger C. Baatrup A. Kassem M. Mygind T. Flow perfusion culture of human mesenchymal stem cells on coralline hydroxyapatite scaffolds with various pore sizes. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2011;97A:251. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]