Abstract

CRLF2 rearrangements, JAK1/2 point mutations, and JAK2 fusion genes have been identified in Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)–like acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), a recently described subtype of pediatric high-risk B-precursor ALL (B-ALL) which exhibits a gene expression profile similar to Ph-positive ALL and has a poor prognosis. Hyperactive JAK/STAT and PI3K/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling is common in this high-risk subset. We, therefore, investigated the efficacy of the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib and the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin in xenograft models of 8 pediatric B-ALL cases with and without CRLF2 and JAK genomic lesions. Ruxolitinib treatment yielded significantly lower peripheral blast counts compared with vehicle (P < .05) in 6 of 8 human leukemia xenografts and lower splenic blast counts (P < .05) in 8 of 8 samples. Enhanced responses to ruxolitinib were observed in samples harboring JAK-activating lesions and higher levels of STAT5 phosphorylation. Rapamycin controlled leukemia burden in all 8 B-ALL samples. Survival analysis of 2 representative B-ALL xenografts demonstrated prolonged survival with rapamycin treatment compared with vehicle (P < .01). These data demonstrate preclinical in vivo efficacy of ruxolitinib and rapamycin in this high-risk B-ALL subtype, for which novel treatments are urgently needed, and highlight the therapeutic potential of targeted kinase inhibition in Ph-like ALL.

Introduction

Survival rates for childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) approach 90% with current combination chemotherapy regimens.1 Intensification of chemotherapy regimens has largely been responsible for dramatic improvements in survival; however, recent modifications have yielded diminishing returns, particularly in a subset of leukemias that are relatively resistant to conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy. The identification of underlying genetic alterations in chemotherapy-resistant subtypes, particularly lesions that drive leukemogenesis and can be targeted with novel therapies, remains an urgent need.

Genome-wide analyses and next-generation sequencing approaches have advanced our understanding of potential leukemogenic mutations in pediatric ALL.2–7 Recently, these analyses identified a cohort of clinically high-risk pediatric B-precursor ALL with gene expression profiles similar to those of Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL (Ph+ ALL, also termed BCR-ABL1–positive ALL).2,4,8 This Ph-like cohort suffers high rates of relapse and mortality. The similarity to Ph+ ALL suggests that aberrant kinase activity may also drive this subset of ALL. Indeed, several lesions affecting kinase activity and cytokine signaling have recently been identified in Ph-like ALL.9 Rearrangements in CRLF2 (cytokine receptor-like factor 2), leading to overexpression of this component of the heterodimeric cytokine receptor for thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), are present in up to 7% of childhood B-precursor ALL overall,10–12 represent approximately half of Ph-like ALLs,8 and are highly associated with point mutations in Janus kinase (JAK) family members.11,13–15 Moreover, CRLF2 overexpression is an independent negative prognostic factor in high-risk pediatric B-ALL.16

The frequency of genetic alterations in CRLF2 and JAK2 in high-risk B-ALL and Down syndrome–associated ALL10,17 suggests that these lesions may be key events in leukemogenesis. Consistent with its role in early B-cell development, we have previously demonstrated that TSLP stimulates proliferation of precursor B-ALL cell lines.18,19 Similarly, JAK signaling has been implicated in BCR-ABL1–mediated transformation.20 Furthermore, the combination of CRLF2 rearrangement and JAK2 mutations induces transformation of the murine B-progenitor cell line, Ba/F3.10 The direct downstream targets of TSLP and its receptor, CRLF2, have not been fully elucidated; however, mutant JAK2 physically associates with CRLF210 and the JAK/STAT pathway appears to be involved in CRLF2 signaling.11,21 Moreover, TSLP-mediated proliferation can be partially abrogated by treatment with rapamycin (sirolimus),18 suggesting a role for the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway as well. We previously showed aberrant JAK/STAT and PI3K/mTOR signaling in CRLF2-overexpressing ALL cell lines and primary human samples in vitro.19 We thus hypothesized that inhibition of these hyperactive signaling networks has therapeutic relevance.

To model Ph-like ALL in vivo, we used xenograft models derived from primary human ALL samples. This study establishes the in vivo efficacy of the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib and the mTOR inhibitor (MTI) rapamycin in Ph-like ALL cases with JAK-activating lesions with or without CRLF2 rearrangements, indicating that the JAK/STAT and PI3K/mTOR pathways are viable therapeutic targets in this difficult to treat subset of ALL.

Methods

Patient samples

Previously banked diagnostic specimens (peripheral blood or bone marrow) from patients treated on the Children's Oncology Group (COG) P9906 high-risk B-precursor ALL trial were used for xenograft studies. All cases were CRLF2-rearranged and/or part of the previously described Ph-like cluster.4,8,13 Patient characteristics and treatment used in the P9906 trial have been previously described.22 Informed consent for use of diagnostic specimens for future research was obtained from patients or their guardians according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and protocols were approved by the National Cancer Institute and institutional review boards of participating institutions.

Establishment of xenograft models

Xenograft models were established as previously described23,24 with modifications described herein. Primary leukemia cells from peripheral blood or bone marrow were intravenously injected into nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid, also termed NOD/SCID) Il2rgtm1wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice. Splenocytes harvested from successfully engrafted xenografts were reinjected (106 cells/mouse) to create secondary and tertiary xenografts for treatment trials. Engraftment was determined by flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood using antibodies against human CD19 and CD45 (CD19-PE, CD45–allophycocyanin [APC]; Beckman Coulter). Cells were collected on an Accuri CSampler flow cytometer (Accuri Cytometers; BD Biosciences), and analysis was performed with FlowJo Version 7.6 software (TreeStar). Once xenografts had engrafted with sufficient disease burden to detect > 1% peripheral huCD19+/45+ blasts, mice were randomized to treatment or vehicle. Ruxolitinib (INCB018424, provided by Incyte) at 30 mg/kg/d or vehicle (40% dimethyl acetamide, 60% propylene glycol) was given by continuous subcutaneous infusion using implanted mini-osmotic pumps (Alzet). Continuous infusion was chosen to mimic pharmacokinetics and drug levels of daily oral dosing in humans.25 Rapamycin (5 mg/kg) or vehicle (5% dextrose in water) was given 5 days a week by oral gavage.26,27 Studies were terminated and mice were killed after 3-4 weeks of treatment, when vehicle-treated mice became ill according to standard parameters set on the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol. Spleen and bone marrow were harvested at the time of sacrifice. Disease burden was assessed every 7-14 days by flow cytometric measurement of huCD19+/45+ blast count in peripheral blood, using CountBright absolute counting beads (Invitrogen) as described in the manufacturer's instructions, and at sacrifice, by measuring absolute splenic blasts (total splenic cell count × %huCD19+/45+ cells). Deaths within 72 hours of pump placement were considered secondary to anesthesia or surgery, and these mice were excluded.

For pharmacodynamic studies, 2-3 mice per arm were treated for 72 hours. Treatment was started when peripheral blast percentage reached > 50%, which corresponded to average splenic blast percentages of 58%-90%. Xenografts I, III, and VIII were the exception, in that mice succumbed to disease when peripheral blast percentage approached 50%; therefore, pharmacodynamic studies in these xenografts were performed at a lower peripheral blast count, but similar average splenic blast percentages of 51%-77%. After 72 hours of treatment, mice were killed, and spleens were harvested for immunoblotting and phosphoflow cytometry. All experiments were conducted on protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Review Board of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Immunoblotting

Lysates for immunoblotting were prepared from spleen cell pellets. Mouse spleens were homogenized and filtered to form single-cell suspensions. Erythrocytes were lysed with Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) ammonium chloride, and cell pellets were snap-frozen at −80°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) containing Complete Mini (Roche Applied Biosciences) and 1mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich) and lysed by sonication. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis on NuPAGE 4%-12% SDS-PAGE gradient gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Invitrogen). Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies to ribosomal protein S6, phosphorylated S6 (Ser235/236), STAT5, phosphorylated STAT5 (Tyr694; all from Cell Signaling Technology), and actin (Sigma-Aldrich). Signal was detected by chemiluminescence using LumiGLO reagent (Cell Signaling Technology), and densitometric analysis performed with UnScanIt Version 6.1 software (Silk Scientific).

Phosphoflow analysis

Phosphoflow cytometry was performed as previously described.28 Briefly, harvested spleens were homogenized and filtered to form single-cell suspensions. Erythrocytes were lysed with Tris ammonium chloride and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 107 cells were isolated for phosphoflow. For ex vivo stimulation conditions, spleen cell suspensions were incubated with 25 ng/mL human recombinant TSLP (R&D Systems) for 30 minutes at 37°C. An aliquot from each sample was incubated with 125μM pervanadate (prepared from sodium orthovanadate and peroxide; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 37°C and served as a positive control. Untreated and stimulated cells were fixed with ACS-grade paraformaldehyde at a final concentration of 1.5% for 10 minutes at room temperature. After washing in PBS with 4% fetal bovine serum (FBS), cells were permeabilized with 90% ACS-grade methanol in PBS and stored at −20°C. After rehydration in PBS with 4% FBS, permeabilized cells were incubated with cocktails of antibodies against human ALL cell-surface markers and intracellular phosphoproteins before multiparametric analysis on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Antibodies were from eBioscience (TSLPR-PE), BD Biosciences (CD10-PE-Cy7, CD19-APC-Cy7, pSTAT5Y694-Ax647, pS6S235/S236-Ax488, p4EBP1T37/T46-Ax647), Cell Signaling Technologies (unconjugated pJAK2Y1007/Y1008), and Invitrogen (secondary goat anti–rabbit IgG-Pacific Blue). The pJAK2 antibody has some cross-reactivity with pJAK1, which is also inhibited by ruxolitinib. CRLF2-rearranged or nonrearranged ALL samples were gated on the CD10+/CD19+/TSLPR+ or CD10+/CD19+ populations, respectively, for analysis of intracellular phosphosignaling. Digital phosphoflow cytometry data were recorded as raw data, as well as transformed with the inverse hyperbolic sine (arcsinh) equation via Cytobank to display and compare intensity values and to correct for large variances of some fluorophores.29 Data were reported as median fluorescence intensities, then normalized to the phosphorylation levels of vehicle-treated mice for data display.

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using Prism Version 5 software (GraphPad) to determine statistical significance of peripheral blast counts (P values represent the interaction between time and treatment). Spleen blast counts were analyzed by 1-sided t test. Survival studies were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test used to compare treatments.

Results

To perform preclinical in vivo studies with signal transduction inhibitors, we developed multiple xenograft models of human Ph-like ALL. Diagnostic specimens from 21 patients treated on the COG P9906 high-risk B-precursor ALL trial were intravenously injected into immunodeficient mice, and engraftment was determined by flow cytometry of peripheral blood for human CD19+/CD45+ blasts. Eighteen of 21 samples, which were CRLF2-rearranged and/or part of the previously described Ph-like cluster,8,13 successfully engrafted in NSG mice. These 18 samples represented each of 4 Ph-like subgroups: JAK-mutated (JAKm) or wild-type (JAKwt) and CRLF2-rearranged (CRLF2R) or nonrearranged (CRLF2NR). Limited data suggest that the highly immunodeficient NSG strain provides increased engraftment efficiency compared with the NOD/SCID strain,30 historically a more frequently used xenograft model. We compared the NSG strain to the NOD/SCID strain in efficiency of engraftment of samples from this cohort. Seven of 9 samples engrafted in NOD/SCID mice; however, on average, time to engraftment was delayed and engraftment was less robust (data not shown). Therefore, the NSG strain was chosen to model Ph-like ALL.

For therapeutic studies of the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib and the MTI rapamycin, we selected leukemias from each of the 4 subgroups to assess potential differential efficacy. JAK mutation and CRLF2 rearrangement status for each xenograft is listed in Table 1, as are additional relevant mutations or rearrangements. The majority of CRLF2-rearranged samples in this study harbored the IGH@-CRLF2 rearrangement, which is twice as common as the P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion in the P9906 cohort.13 As the P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion is more common in other ALL cohorts,10,12,16 we also included a sample with this lesion. Once xenografts had sufficient disease burden to detect > 1% peripheral blasts (representing considerable tissue burden in bone marrow and spleen23), mice were randomized to receive a signal transduction inhibitor or vehicle. Disease burden was assessed by peripheral blast count and, at sacrifice, by splenic blast count. Of 207 xenografted mice studied (55 treated with ruxolitinib, 50 with rapamycin, 102 vehicle controls), 11 were excluded from analysis because of missing data points. Of these, there were 10 early deaths, 9 attributable to surgical complications after subcutaneous pump placement, and 1 died of an unknown cause. One ruxolitinib-treated mouse, excluded for missing data points, experienced a wound dehiscence at the subcutaneous pump surgical site, requiring pump removal. We were unable to collect peripheral blood because of illness at the time of wound dehiscence. Of note, at the time of sacrifice, the spleen size of this mouse was similar to that of vehicle-treated mice, and the splenic response to ruxolitinib lost significance. We suspected inconsistent and/or poor drug delivery before pump removal because of dehiscence. The remaining exclusions had no effect on study results and were equally distributed between vehicle and ruxolitinib treatments.

Table 1.

CRLF2 rearrangement and JAK mutation status of xenografted ALL samples

| Xenograft no. | TARGET ID/USI | CRLF2 rearrangement | JAK mutation | Other lesions | Ph-like |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 9906_151/PALKTY | P2RY8-CRLF2 | JAK2 QGinsR683 | Yes | |

| II | 9906_258/PAMDRM | IGH@-CRLF2 | JAK2 GPInsR683 | Yes | |

| III | 9906_020/PAKHZT | IGH@-CRLF2 | JAK2 R867Q | Yes | |

| IV | 9906_257/PAMDKS | IGH@-CRLF2 | JAK2 R683G | Yes | |

| V | 9906_037/PAKMVD | Negative | JAK1 S646F | Yes | |

| VI | 9906_196/PALTWS | IGH@-CRLF2 | Negative | No | |

| VII | 9906_084/PAKYEP | Negative | Negative | BCR-JAK2 | Yes |

| VIII | 9906_145/PALJDL | Negative | Negative | IL7R L242 > FPGVC, SH2B3 deletion | Yes |

ALL indicates acute lymphoblastic leukemia; TARGET, therapeutically applicable research to generate effective treatments; and USI, unique specimen identifer.

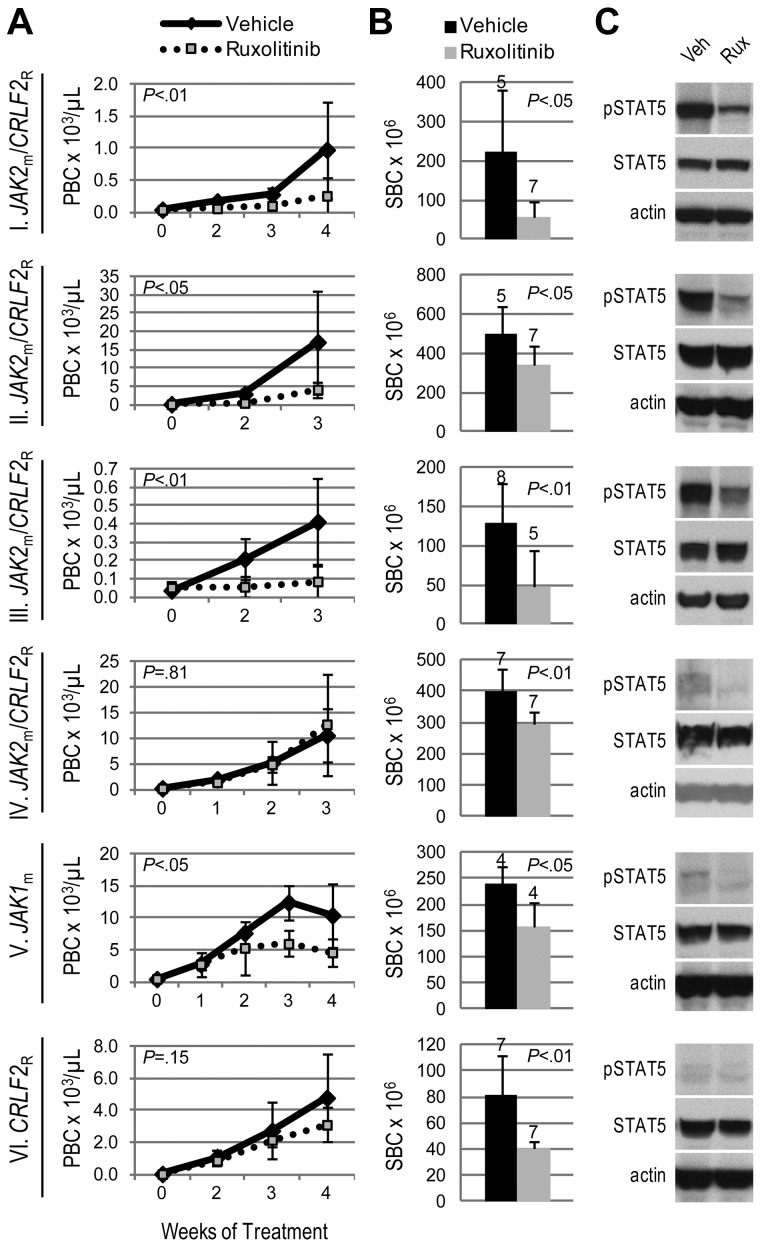

We hypothesized that JAK-mutated ALL would be sensitive to the JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib. Three JAK2m/CRLF2R ALL xenografts (I, II, III), including the sample harboring a P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion, exhibited significantly decreased leukemia burden with ruxolitinib treatment compared with vehicle, evidenced by lower peripheral blast count (Figure 1A) and splenic blast count (Figure 1B). However, 1 JAK2m/CRLF2R ALL xenograft (IV) demonstrated lower splenic blast count, but no difference in peripheral blast count, with ruxolitinib treatment. Xenograft V, which harbors a JAK1 S646F mutation without CRLF2 rearrangement (JAK1m/CRLF2NR), responded to ruxolitinib with lower peripheral and splenic blast counts compared with vehicle. In contrast, ruxolitinib yielded only a partial response (lower splenic blast count with no difference in peripheral blast count) in xenograft VI, which does not harbor a JAK mutation but is CRLF2-rearranged.

Figure 1.

Efficacy of ruxolitinib in xenograft models of Ph-like ALL. Genetic lesions are indicated to the left of each row. (A) Peripheral blast count (PBC) over time in JAK-mutated (JAKm) or wild-type (JAKwt) and CRLF2-rearranged (CRLF2R) or nonrearranged (CRLF2NR) ALL xenografts. Graphed are means and SDs with PBC × 103 per microliter on the vertical axis and weeks of treatment on the horizontal axis; n indicated in panel B. (B) Splenic blast count (SBC) at sacrifice. Means and SDs are graphed with the vertical axis representing absolute SBC × 106; n for each arm indicated above bar. (C) Levels of phosphorylated STAT5 (pSTAT5) by immunoblot. Xenografts were treated with ruxolitinib (rux) or vehicle (veh) for 72 hours, spleens were harvested, and protein lysates subjected to immunoblot for pSTAT5, total STAT5, and actin.

Surprisingly, 2 ALL xenografts with no identified JAK mutation or CRLF2 rearrangement (xenografts VII and VIII) had markedly decreased leukemia burden with ruxolitinib treatment compared with vehicle (Figure 2A-B). Parallel, but independent, identification of lesions resulting in JAK2 activation in both samples was achieved by next-generation sequencing.9 Transcriptome sequencing revealed a BCR-JAK2 rearrangement in the sample corresponding to xenograft VII. We recently reported this rearrangement's identification and in vivo ruxolitinib response in this rare ALL subtype.9 In addition, an SH2B3 deletion and IL7R mutation were discovered in the sample corresponding to xenograft VIII. SH2B3 encodes LNK, a negative regulator of JAK2; therefore, its deletion would be expected to result in JAK2 activation. Taken together, these studies demonstrate the efficacy of ruxolitinib in ALL xenografts with a variety of JAK-activating lesions.

Figure 2.

Activity of ruxolitinib in ALL xenografts with JAK/STAT pathway activation. Genetic lesions are indicated to the left of each row. (A) Peripheral blast count (PBC) over time. Graphed are means and SDs with PBC × 103 per microliter on the vertical axis and weeks of treatment on the horizontal axis; n indicated in panel B. (B) Splenic blast count (SBC) at sacrifice. Means and SDs are graphed with the vertical axis representing absolute SBC × 106; n for each arm indicated above bar. (C) Levels of phosphorylated STAT5 (pSTAT5) by immunoblot. Xenografts were treated with ruxolitinib (rux) or vehicle (veh) for 72 hours, spleens were harvested, and protein lysates subjected to immunoblot for pSTAT5, total STAT5, and actin. (D) Comparison of basal levels of pSTAT5 in vehicle-treated xenografts. A representative immunoblot for pSTAT5, total STAT5, and actin is shown on the left, and quantitation of pSTAT5 signal intensity (normalized to actin signal intensity and graphed relative to xenograft V) in 3 vehicle-treated xenografts is shown on the right.

We assessed JAK activity by phosphorylation of the downstream target STAT5. Levels of phosphorylated (p)STAT5 by immunoblot were consistently decreased in ruxolitinib-treated spleens relative to vehicle (Figures 1C, 2C). Furthermore, xenografts that responded to ruxolitinib (xenografts I, II, III, VII, and VIII) were distinguished from those that showed minimal response (xenografts IV and VI) by substantially higher basal levels of pSTAT5 (Figure 2D). Using STAT5 phosphorylation as a surrogate marker of JAK activity, these data suggest ruxolitinib response may be associated with JAK/STAT pathway activation. For xenograft V, which harbors a JAK1 mutation, pSTAT5 levels did not correspond to ruxolitinib response; therefore, we also assessed levels of pJAK1 and pSTAT3, another downstream target of JAK1 and JAK2. Ruxolitinib-treated spleens demonstrated lower levels of pJAK1, but no consistent decrease in STAT3 phosphorylation, compared with vehicle (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). While ruxolitinib inhibits phosphorylation of STAT3 in patients with myeloproliferative disorders,31 we have not detected inhibition of pSTAT3 by phosphoflow cytometry in CRLF2-rearranged ALL cell lines and patient samples (S.K.T., unpublished data, 2011-2012), possibly reflecting differences in biology.

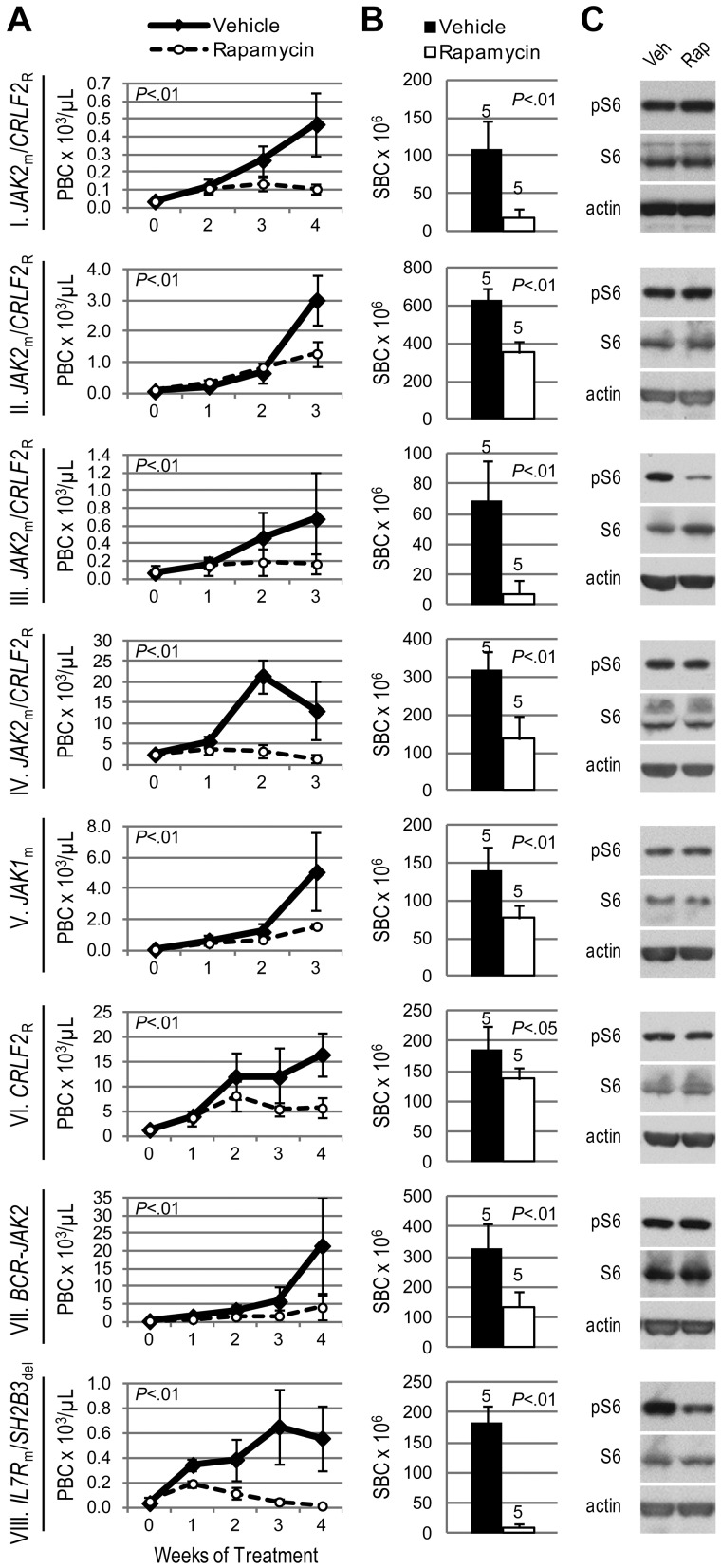

Given the involvement of mTOR in TSLP signaling and BCR-ABL1–positive leukemias,32 we hypothesized that mTOR inhibition has therapeutic relevance in Ph-like ALL. Regardless of JAK mutation or CRLF2 rearrangement status, all 8 ALL xenografts responded to the MTI rapamycin with decreased peripheral and splenic blasts compared with vehicle (Figure 3A-B). A profound response was seen in xenograft VIII, the sample in which we simultaneously discovered an activating mutation in the gene encoding IL7R, which signals in part through the PI3K/mTOR pathway.

Figure 3.

Efficacy of rapamycin in xenograft models of Ph-like ALL. Genetic lesions are indicated to the left of each row. (A) Peripheral blast count (PBC) over time in ALL xenografts. Graphed are means and SDs with PBC × 103 per microliter on the vertical axis and weeks of treatment on the horizontal axis; n indicated in panel B. (B) Splenic blast count (SBC) at sacrifice. Means and SDs are graphed with the vertical axis representing absolute SBC × 106; n for each arm indicated above bar. (C) Levels of phosphorylated ribosomal protein S6 (pS6) by immunoblot. Xenografts were treated with rapamycin (rap) or vehicle (veh) for 72 hours, spleens were harvested, and protein lysates subjected to immunoblot for pS6, total S6, and actin.

We observed constitutive phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6, a downstream target of mTORC1, in all vehicle-treated xenograft spleens by immunoblot (Figure 3C). Phosphorylated S6 (pS6) was decreased compared with vehicle in rapamycin-treated xenografts III and VIII. However, the remaining ALL xenografts showed no change in pS6 levels by immunoblot. To evaluate mTORC2 activity, which is typically insensitive to rapamycin inhibition, we assessed phosphorylation of AKT and found no change in pAKT in rapamycin-treated xenografts (supplemental Figure 2).

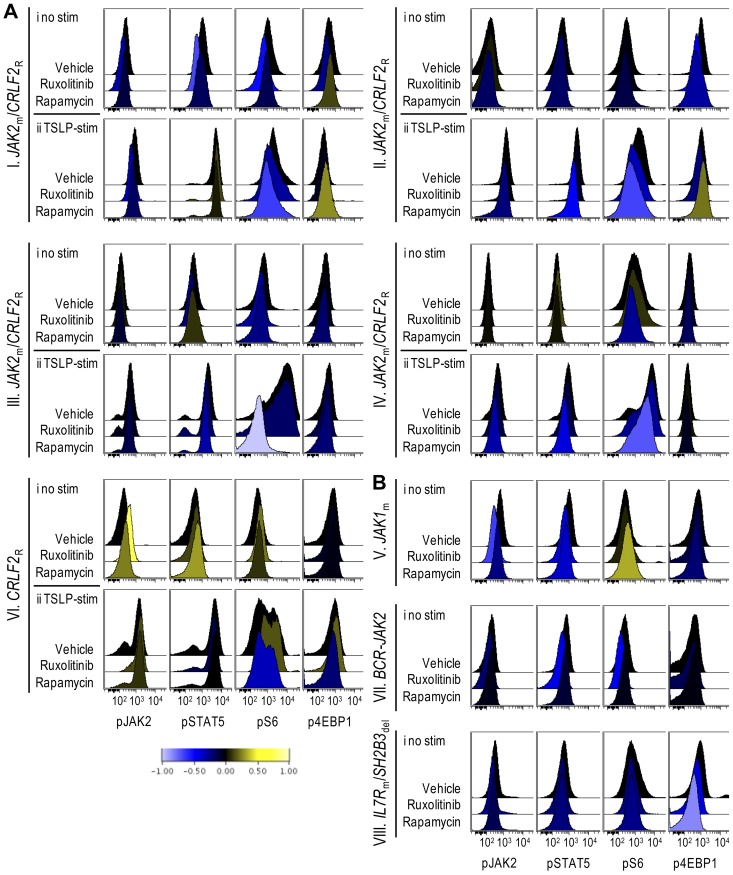

Theoretically, murine cells in splenic lysates could affect immunoblot-based signaling analyses, but are unlikely to do so at the high splenic blast percentages achieved in pharmacodynamic studies. Nevertheless, we turned to phosphoflow cytometry to assess phospho-epitopes more precisely in gated ALL cell populations at a single-cell level. Modest decreases in pS6 and p4EBP1, another downstream target of mTOR, were detectable in rapamycin-treated xenografts (Figure 4Ai,B). To overcome the difficulty of detecting inhibition below basal levels that may occur in biologic phosphoflow assays,19 we assessed the inhibitory effects of ruxolitinib and rapamycin on TSLP-induced phosphorylation of JAK/STAT and PI3K/mTOR pathway signal transduction proteins in vitro, and found that ruxolitinib inhibited TSLP-mediated phosphorylation of STAT5 and S6, while rapamycin decreased TSLP-mediated phosphorylation of S6 in xenograft spleens containing CRLF2-rearranged leukemias (supplemental Figure 3). We then performed ex vivo stimulation with TSLP on leukemia cells obtained from the spleens of xenografts treated with rapamycin in vivo. In CRLF2-rearranged xenografts (I-IV, VI) rapamycin treatment decreased TSLP-mediated phosphorylation of S6 and 4EBP1 (Figure 4Aii). In contrast, xenografts V, VII, and VIII, which are not CRLF2-rearranged and thus did not respond to ex vivo TSLP stimulation (data not shown), showed little or no change in pS6 (Figure 4B), despite clinical responses to rapamycin. The degree of inhibition of pS6, therefore, did not correlate with rapamycin response, consistent with other studies.33,34 Decreased pJAK2 and pSTAT5 were also apparent in some rapamycin-treated xenografts, suggesting possible interconnection between these pathways.

Figure 4.

Phosphoflow analysis of in vivo target inhibition. ALL xenografts were treated with vehicle, ruxolitinib, or rapamycin for 72 hours, spleens were harvested, and cells were gated on CD10+/CD19+/TSLPR+ populations (CRLF2R xenografts) or CD10+/CD19+ populations (CRLF2NR xenografts) and analyzed by phosphoflow cytometry for levels of phosphorylated (p)JAK2, STAT5, S6, and 4EBP1. Data were arcsinh-transformed and are represented as histograms of median fluorescent intensities. Down-regulation and up-regulation of phosphorylation relative to vehicle controls are represented by shift to the left (blue) and right (yellow), respectively, on the horizontal axis per the colorimetric scale (bottom). (A) Histograms of (i) unstimulated and (ii) TSLP-stimulated CRLF2R xenografts. (B) Histograms of unstimulated CRLF2NR xenografts.

Phosphoflow cytometry of ruxolitinib-treated xenografts demonstrated decreased phosphorylated STAT5 (pSTAT5) and JAK2 (pJAK2) relative to vehicle in xenografts that displayed a marked clinical response (Figure 4B, xenografts VII-VIII). In addition, ruxolitinib inhibited pS6 and p4EBP1 in some xenografts. In general, flow cytometric detection of JAK/STAT pathway inhibition below basal levels appeared less robust than inhibition demonstrated via immunoblotting, possibly secondary to differences in antibody sensitivity.

Last, we determined whether rapamycin conferred a survival advantage in Ph-like ALL xenografts. We chose 2 ALL cases which were representative of a good response and an intermediate response to rapamycin by peripheral and splenic blast counts. Rapamycin significantly prolonged survival compared with vehicle of both xenograft IV (Figure 5A, median survival 63 days vs 23 days, P < .01) and xenograft V (Figure 5B, median survival 91 days vs 58 days, P < .01). We were unable to perform survival studies with ruxolitinib because of continuous administration, which would require repeated surgical placement of subcutaneous pumps.

Figure 5.

Rapamycin prolongs survival of JAK-mutated ALL xenografts. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of xenografts (A) IV and (B) V, demonstrating percent surviving (vertical axis) from the start of treatment (horizontal axis represents days of treatment) with rapamycin (n = 5) or vehicle (n = 5). Median survival of each arm and P values, determined by log-rank test, are indicated.

Discussion

Ph-like ALL comprises approximately 10%-15% of clinically high-risk pediatric B-precursor ALL.2,4,8 This subgroup of patients has a significantly inferior outcome compared with non–Ph-like cases in all cohorts examined (M.L.L., J. Zhang, R.C.H., K.G.R., D. Payne-Turner, H. Kang, G. Wu, X. Chen, J. Becksfort, M. Edmonson, K. Buetow, W. L. Carroll, I.M.C., B. Wood, M. J. Borowitz, M. Devidas, D. S. Gerhard, P. Bowman, E. Larsen, N. Winick, E. Raetz, M. Smith, J. R. Downing, C.L.W., C.G.M, S.P.H., manuscript submitted, February 2012).2,4 It is clear that therapy modifications or additions are urgently needed for Ph-like ALL. As toxicity thresholds are reached and chemotherapy modifications yield fewer returns, rationally designed targeted therapies become not only preferable, but necessary.

Dramatic improvements in overall survival achieved in Ph+ ALL with the addition of imatinib set the paradigm for molecularly targeted therapy.35 Promising targets in Ph-negative ALL are emerging through the advancement of high-throughput genome-wide analyses and next-generation sequencing techniques.9 Advanced genomic analyses have identified several kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like ALL, including mutations and rearrangements that result in activation of JAKs.3,8,14,15 Furthermore, alterations in cytokine signaling which can result in hyperactive kinase networks, for example, through the TSLP receptor CRLF2, have also been recognized in this subtype.3,8,13,15

Frequent alterations in JAK2 and CRLF2 as well as aberrant signaling through associated pathways led us to hypothesize that the JAK/STAT and PI3K/mTOR pathways are relevant targets in some cases of Ph-like ALL. Using NSG xenograft models of primary human ALL, we achieved measurable engraftment of 85% of ALL samples attempted, making this model a robust platform for preclinical testing of novel therapies. In this study, we demonstrate the in vivo efficacy of the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib and the MTI rapamycin in specific Ph-like ALL subsets. While ruxolitinib has been evaluated in myeloproliferative disorders with JAK2 V617F mutations and efficacy has been demonstrated in phase 1/2 and 3 studies,31,36,37 this is the first report of in vivo efficacy in multiple ALL patient samples. As such, these studies support the advancement of ruxolitinib into clinical trials for pediatric ALL.

Our group and others have previously demonstrated MTI efficacy in preclinical models of ALL.23,26,38–41 In those studies, the single-agent activity of MTIs was variable in B-ALL, but more promising in T-cell ALL and high-risk subsets of B-ALL, such as Ph+ ALL.38,40,41 However, rapamycin displays broad anti-ALL activity in combination with chemotherapeutic agents, including dexamethasone, methotrexate, or doxorubicin.24,41–44 To move MTIs successfully into clinical trials, it would be ideal to identify particular subsets of B-ALL that are more likely to respond. Here we show that a leukemia with an activating mutation in IL7R and several leukemias with altered CRLF2 and JAK/STAT signaling are sensitive to rapamycin. Whether rapamycin's efficacy is related to broad ALL activity or specific to these altered signaling pathways warrants further investigation. Nonetheless, the efficacy of rapamycin in all 8 B-ALL cases tested in this study suggests that Ph-like ALL may be more sensitive to MTIs than other B-ALL subsets. Future studies will compare the efficacy of MTIs in Ph-like ALL to other B-ALL subtypes and will test the activity of other agents that target the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. In addition, it will be important to determine whether rapamycin sensitivity applies to all leukemias with CRLF2 overexpression as CRLF2 overexpression can be mediated by other mechanisms.15,16 We have assessed 4 cases harboring the IGH@-CRLF2 rearrangement, which comprises the majority of cases in the P9906 cohort,13 and 1 case with the P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion, which is more common in other ALL cohorts.10,12,16 CRLF2-overexpressing leukemias represent up to 15% of pediatric high-risk ALL3,8,10,13,15 and more than 50% of Down syndrome–associated ALL.10,17 In addition, recurrent IL7R mutations have been identified in T-precursor, B-precursor, and early T-cell precursor (ETP) ALL45–47; therefore, the therapeutic potential of mTOR inhibition in these subtypes has broad clinical implications.

To date, little data exist on effective treatment strategies for CRLF2-rearranged and JAK2-mutated ALL. Recently, Weigert et al demonstrated efficacy of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) inhibition in CRLF2-rearranged precursor B ALL, but reported minimal activity of a novel JAK2 inhibitor, BVB808.48 By contrast, we demonstrate in vivo efficacy of the JAK1/2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, in 6 ALL xenografts with JAK-activating lesions. The Weigert study primarily used in vitro assays, with confirmation in a xenograft model. Differences in study design, length of treatment, potency, and individual leukemia sensitivity may explain this discrepancy. In addition, our larger sample size (8 ALL xenografts tested compared with 2) provided increased power to detect efficacy and allowed identification of differential sensitivity. Furthermore, ruxolitinib is currently being investigated in a COG phase 1 trial, making our studies directly clinically relevant.

It should be noted that neither ruxolitinib nor rapamycin induced a complete remission, rather they decreased leukemia burden in peripheral blood and spleen compared with vehicle-treated mice. This is a common finding with the NSG xenograft model, as most single-agent therapies do not result in a complete response. Future work will include combining the 2 pathway inhibitors and combining each inhibitor with cytotoxic chemotherapy commonly used to treat ALL. Our studies were not designed to assess duration of response. To compare splenic disease burden, each study terminated when the vehicle arm became ill. However, we do show that rapamycin conferred a survival advantage in 2 representative Ph-like ALL cases tested. We were unable to perform survival studies with ruxolitinib because of the lifespan of subcutaneous pumps required for continuous administration. In the future, availability of ruxolitinib in an oral chow formulation may overcome this issue. Despite these limitations, the responses to these inhibitors as single agents in a disease that relies on multiagent therapy are notable and suggest they represent viable targeted therapies.

Several unanticipated outcomes of these studies further support our hypothesis that leukemias with JAK pathway activation respond to ruxolitinib. Two samples with no known JAK mutations or CRLF2 rearrangements identified by microarray analysis, fluorescence in situ hybridization, and targeted sequencing responded to both ruxolitinib and rapamycin. The first, xenograft VII, was subsequently discovered to harbor a BCR-JAK2 fusion, explaining its response to ruxolitinib.9 The second, xenograft VIII, was identified in that same study to carry an IL7R mutation and SH2B3 (LNK) deletion. As a negative regulator of JAK2, decreased expression of LNK leads to increased JAK2 activity, suggesting that this deletion has the same functional consequences as JAK2-activating mutations and translocations.49–51 It is not surprising then that JAK inhibition is effective in this xenograft. In addition, IL7R signals through the JAK/STAT (specifically, JAK1) and PI3K/mTOR pathways, and gain-of-function mutations result in their constitutive activation.26,45,52–54 JAK1/2 and mTOR inhibition, therefore, would be expected to abrogate this signaling.

Characterization of the full repertoire of genomic and proteomic alterations resulting in the “kinase-active” gene expression profile of Ph-like ALL is incomplete. While specific genetic mutations can be helpful in identifying potential targets for novel therapies, the previously mentioned examples of unexpected responses argues for the use of functional assays to predict response. Patients without identified JAK mutation may nevertheless exhibit hyperactive pathway signaling, and JAK/STAT pathway activation may be more important than lesions in JAK kinases in predicting response to inhibitors. In agreement with this hypothesis, our studies suggest a possible link between ruxolitinib response and STAT5 phosphorylation. ALL xenografts that responded to ruxolitinib showed higher levels of phosphorylated STAT5, a marker of JAK/STAT pathway activation, compared with those exhibiting minimal responses. Sample size limitations preclude an analysis of correlation; however, on confirmation of this potential association in larger analyses, development of clinically applicable immunoblot or flow-based assays of phosphorylated STAT5 could be used to predict response to ruxolitinib. Rapamycin response did not correlate with S6 phosphorylation, however. This finding is consistent with other reports of MTI efficacy in leukemia, which found little biochemical correlation with the degree of response.33,34 Nevertheless, these ALL xenografts exhibit constitutive mTOR activation, suggesting an association between pathway hyperactivity and rapamycin efficacy. Each of the xenografts in this cohort responded to rapamycin; therefore, it was not possible to correlate mTOR activation with response. Continued focus on functional consequences of genomic alterations and how these might forecast responses to lesion-directed therapies will help distinguish useful targets.

Imatinib therapy in Ph+ ALL set the paradigm for targeted therapy and introduced the exciting prospect that targets could be identified and inhibited in other cancers. This hypothesis has yet to be proven in non-Ph+ ALL. We have established the preclinical in vivo efficacy of ruxolitinib and rapamycin, elevating the potential of molecularly targeted therapies in pediatric ALL and suggesting a role for these therapies in at least some subsets of Ph-like ALL, a subtype of high-risk ALL for which cytotoxic chemotherapy yields suboptimal cure rates. Based in part on these data, both ruxolitinib and temsirolimus (a parenteral ester of rapamycin) are currently being investigated in multicenter, early phase clinical trials for children with relapsed or refractory leukemia. Future studies aimed at identifying patients with Ph-like ALL and other kinase-activating lesions at diagnosis will help select patients who may benefit from molecularly targeted therapy. Moreover, functional assays of JAK/STAT pathway activation could be made clinically available to select patients in whom clinical responses to kinase inhibitors would be predicted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Abramson Cancer Center Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Resource Laboratory.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA102646 and CA1116660 (S.A.G.), R56A1099301 (D.T.T.), the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Patient Impact Initiative, Larry and Helen Hoag Foundation Clinical Translational Research Career Development Award (D.T.T.), American Cancer Society Research grant RSG0507101 (S.A.G.), the Weinberg Fund of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (S.A.G.), the University of Pennsylvania Cancer Research Training Program National Research Service Award T32CA009615-21 and the When Everyone Survives Foundation (S.L.M.), the Abramson Cancer Center's Paul Calabresi Career Development Award K12CA076931 (S.L.M. and S.K.T.), a Conquer Cancer Foundation/American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award (S.K.T.), an Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation Young Investigator Award (S.K.T.), the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (K.G.R.), the American Lebanese and Syrian Associated Charities of St Jude Children's Research Hospital (K.G.R. and C.G.M.), a Stand Up To Cancer Innovative Research Grant (C.G.M.), a St Baldrick's Research Grant (M.L.L.), and grants to the Children's Oncology Group including the COG Chair's grant (CA98543) and a supplement to support the TARGET Project, U10 CA98413 (COG Statistical Center), and U24 CA114766 (COG Specimen Banking). M.L.L. is a Clinical Scholar of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. C.G.M. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences and a St Baldrick's Scholar. S.P.H. is the Ergen Family Chair in Pediatric Cancer.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.L.M. designed the study, performed xenograft studies, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; S.K.T. performed phosphoflow experiments and assisted in manuscript preparation; T.V., J.W.H., C.S., and D.M.B. established xenografts and contributed to xenograft experiments; K.G.R. and I-M.C. performed validation of rearrangements and sequence mutations; A.E.S. contributed to statistical analysis; J.R.C. contributed to initial drug screening experiments; C.G.M. contributed transcriptome and whole genome sequencing data; C.G.M., S.P.H., R.C.H., and C.L.W. oversaw sample selection and provided samples; J.S.F. provided ruxolitinib and guidance on administration; M.L.L. supervised COG biology studies and oversaw phosphosignaling experiments; and S.A.G. and D.T.T. designed and oversaw the study and assisted in manuscript preparation and editing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.S.F. is an employee of Incyte Corporation. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David T. Teachey, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, CTRB 3008, 3501 Civic Center Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: teacheyd@e-mail.chop.edu.

References

- 1.Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1663–1669. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Den Boer ML, van Slegtenhorst M, De Menezes RX, et al. A subtype of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with poor treatment outcome: a genome-wide classification study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70339-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, Mullighan CG, Harvey RC, et al. Key pathways are frequently mutated in high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Blood. 2011;118(11):3080–3087. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullighan CG, Su X, Zhang J, et al. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(5):470–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446(7137):758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuiper RP, Schoenmakers EF, van Reijmersdal SV, et al. High-resolution genomic profiling of childhood ALL reveals novel recurrent genetic lesions affecting pathways involved in lymphocyte differentiation and cell cycle progression. Leukemia. 2007;21(6):1258–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawamata N, Ogawa S, Zimmermann M, et al. Molecular allelokaryotyping of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemias by high-resolution single nucleotide polymorphism oligonucleotide genomic microarray. Blood. 2008;111(2):776–784. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Wang X, et al. Identification of novel cluster groups in pediatric high-risk B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with gene expression profiling: correlation with genome-wide DNA copy number alterations, clinical characteristics, and outcome. Blood. 2010;116(23):4874–4884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts KG, Morin RD, Zhang J, et al. Genetic alterations activating kinase and cytokine receptor signaling in high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(2):153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullighan CG, Collins-Underwood JR, Phillips LA, et al. Rearrangement of CRLF2 in B-progenitor- and Down syndrome-associated acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41(11):1243–1246. doi: 10.1038/ng.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell LJ, Capasso M, Vater I, et al. Deregulated expression of cytokine receptor gene, CRLF2, is involved in lymphoid transformation in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(13):2688–2698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ensor HM, Schwab C, Russell LJ, et al. Demographic, clinical, and outcome features of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and CRLF2 deregulation: results from the MRC ALL97 clinical trial. Blood. 2011;117(7):2129–2136. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-297135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Chen IM, et al. Rearrangement of CRLF2 is associated with mutation of JAK kinases, alteration of IKZF1, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, and a poor outcome in pediatric B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(26):5312–5321. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullighan CG, Zhang J, Harvey RC, et al. JAK mutations in high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(23):9414–9418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811761106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoda A, Yoda Y, Chiaretti S, et al. Functional screening identifies CRLF2 in precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(1):252–257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911726107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen IM, Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, et al. Outcome modeling with CRLF2, IKZF1, JAK, and minimal residual disease in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children's Oncology Group study. Blood. 2012;119(15):3512–3522. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-394221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hertzberg L, Vendramini E, Ganmore I, et al. Down syndrome acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a highly heterogeneous disease in which aberrant expression of CRLF2 is associated with mutated JAK2: a report from the International BFM Study Group. Blood. 2010;115(5):1006–1017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-235408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown VI, Hulitt J, Fish J, et al. Thymic stromal-derived lymphopoietin induces proliferation of pre-B leukemia and antagonizes mTOR inhibitors, suggesting a role for interleukin-7Ralpha signaling. Cancer Res. 2007;67(20):9963–9970. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tasian SK, Doral MY, Borowitz MJ, et al. Aberrant STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathway signaling occurs in human CRLF2-rearranged B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(4):833–842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-389932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danial NN, Rothman P. JAK-STAT signaling activated by Abl oncogenes. Oncogene. 2000;19(21):2523–2531. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpino N, Thierfelder WE, Chang MS, et al. Absence of an essential role for thymic stromal lymphopoietin receptor in murine B-cell development. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(6):2584–2592. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2584-2592.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowman WP, Larsen EL, Devidas M, et al. Augmented therapy improves outcome for pediatric high risk acute lymphocytic leukemia: results of Children's Oncology Group trial P9906. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(4):569–577. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teachey DT, Obzut DA, Cooperman J, et al. The mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 induces apoptosis and inhibits growth in preclinical models of primary adult human ALL. Blood. 2006;107(3):1149–1155. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teachey DT, Sheen C, Hall J, et al. mTOR inhibitors are synergistic with methotrexate: an effective combination to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112(5):2020–2023. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fridman JS, Li J, Caulder E, et al. Selective JAK inhibition is efficacious against multiple myeloma cells and reverses the protective effects of cytokine and stromal cell support [abstract]. Haematologica. 2008;93(Suppl 1):381. Abstract 0956. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown VI, Fang J, Alcorn K, et al. Rapamycin is active against B-precursor leukemia in vitro and in vivo, an effect that is modulated by IL-7-mediated signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(25):15113–15118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436348100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teachey DT, Obzut DA, Axsom K, et al. Rapamycin improves lymphoproliferative disease in murine autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS). Blood. 2006;108(6):1965–1971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotecha N, Flores NJ, Irish JM, et al. Single-cell profiling identifies aberrant STAT5 activation in myeloid malignancies with specific clinical and biologic correlates. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotecha N, Krutzik PO, Irish JM. Web-based analysis and publication of flow cytometry experiments. Curr Protoc Cytom. 2010 doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy1017s53. Chapter 10:Unit 10.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agliano A, Martin-Padura I, Mancuso P, et al. Human acute leukemia cells injected in NOD/LtSz-scid/IL-2Rgamma null mice generate a faster and more efficient disease compared to other NOD/scid-related strains. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(9):2222–2227. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verstovsek S, Kantarjian H, Mesa RA, et al. Safety and efficacy of INCB018424, a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1117–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ly C, Arechiga AF, Melo JV, Walsh CM, Ong ST. Bcr-Abl kinase modulates the translation regulators ribosomal protein S6 and 4E-BP1 in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells via the mammalian target of rapamycin. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):5716–5722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perl AE, Kasner MT, Tsai DE, et al. A phase I study of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor sirolimus and MEC chemotherapy in relapsed and refractory acute myelogenous leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(21):6732–6739. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rizzieri DA, Feldman E, Dipersio JF, et al. A phase 2 clinical trial of deforolimus (AP23573, MK-8669), a novel mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(9):2756–2762. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schultz KR, Bowman WP, Aledo A, et al. Improved early event-free survival with imatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children's Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5175–5181. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrison C, Kiladjian JJ, Al-Ali HK, et al. JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):787–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Kolb EA, et al. Initial testing (stage 1) of the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(4):799–805. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teachey DT, Grupp SA, Brown VI. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors and their potential role in therapy in leukaemia and other haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2009;145(5):569–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janes MR, Limon JJ, So L, et al. Effective and selective targeting of leukemia cells using a TORC1/2 kinase inhibitor. Nat Med. 2010;16(2):205–213. doi: 10.1038/nm.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang C, Ryu Y-K, Chen TZ, Hall CP, Webster DR, Kang MH. Synergistic activity of rapamycin and dexamethasone in vitro and in vivo in acute lymphoblastic leukemia via cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Leuk Res. 2012;36(3):342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Batista A, Barata JT, Raderschall E, et al. Targeting of active mTOR inhibits primary leukemia T cells and synergizes with cytotoxic drugs and signaling inhibitors. Exp Hematol. 2011;39(4):457.e3–472.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Gorlick R, et al. Stage 2 combination testing of rapamycin with cytotoxic agents by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(1):101–112. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei G, Twomey D, Lamb J, et al. Gene expression-based chemical genomics identifies rapamycin as a modulator of MCL1 and glucocorticoid resistance. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(4):331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shochat C, Tal N, Bandapalli OR, et al. Gain-of-function mutations in interleukin-7 receptor-alpha (IL7R) in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemias. J Exp Med. 2011;208(5):901–908. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zenatti PP, Ribeiro D, Li W, et al. Oncogenic IL7R gain-of-function mutations in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):932–939. doi: 10.1038/ng.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481(7380):157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weigert O, Lane AA, Bird L, et al. Genetic resistance to JAK2 enzymatic inhibitors is overcome by HSP90 inhibition. J Exp Med. 2012;209(2):259–273. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bersenev A, Wu C, Balcerek J, et al. Lnk constrains myeloproliferative diseases in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):2058–2069. doi: 10.1172/JCI42032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gery S, Cao Q, Gueller S, Xing H, Tefferi A, Koeffler HP. Lnk inhibits myeloproliferative disorder-associated JAK2 mutant, JAK2V617F. J Leukocyte Biol. 2009;85(6):957–965. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0908575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oh ST, Simonds EF, Jones C, et al. Novel mutations in the inhibitory adaptor protein LNK drive JAK-STAT signaling in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;116(6):988–992. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corcoran AE, Smart FM, Cowling RJ, Crompton T, Owen MJ, Venkitaraman AR. The interleukin-7 receptor alpha chain transmits distinct signals for proliferation and differentiation during B lymphopoiesis. EMBO J. 1996;15(8):1924–1932. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goetz CA, Harmon IR, O'Neil JJ, Burchill MA, Farrar MA. STAT5 activation underlies IL7 receptor-dependent B cell development. J Immunol. 2004;172(8):4770–4778. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Venkitaraman AR, Cowling RJ. Interleukin-7 induces the association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with the alpha chain of the interleukin-7 receptor. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24(9):2168–2174. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.