Abstract

We analyze the structure of space-time focusing of spatially-chirped pulses using a technique where each frequency component of the beam follows its own Gaussian beamlet that in turn travels as a ray through the system. The approach leads to analytic expressions for the axially-varying pulse duration, pulse-front tilt, and the longitudinal intensity profile. We find that an important contribution to the intensity localization obtained with spatial-chirp focusing arises from the evolution of the geometric phase of the beamlets.

OCIS codes: (320.7160) Ultrafast technology, (220.2560) Propagation methods, (320.1590) Chirping

1. Introduction

Typically, spatial and angular chirp in ultrafast optical systems is treated as a misalignment (e.g. [1]), but recent work in nonlinear microscopy [2–4], micromachining [5, 6] and waveguide writing [7] has taken advantage of the special properties of these beams. When a beam that has transverse spatial chirp is focused with a lens or curved mirror, the axial intensity is strongly localized because the pulse duration is not its shortest until all frequency components are fully overlapped. The strong localization that results from this simultaneous space-time focusing (SSTF) is useful for multiphoton microscopy because it improves the axial resolution for wide-field imaging. In micromachining, we have shown that it strongly suppresses nonlinear propagation in a medium along the way to the focus, allowing machining on the back side of a transparent medium or on a surface immersed in water [5]. The spatio-temporal structure of these pulses is quite interesting: there is a strong pulse front tilt at the focus [8] (which appears to be responsible for the nonreciprocal writing effect [6, 9, 10]), and adjustment of the input spectral chirp can move the focus in the axial direction [11]. The pulse front tilt has been exploited in several other areas, such as traveling-wave pumping of x-ray lasers [12], achromatic phase matching of frequency doubling [13], and pulse front matching for THz generation in crystals [14]. Nonlinear effects can be suppressed as the beam propagates through a medium to the target, a great advantage for any application that requires high-energy beam delivery through a medium.

The detailed spatio-temporal structure of these beams has been calculated directly with Fresnel propagation [3]. To provide more insight into the nature of the spatio-temporal coupling and to allow generalization to other systems, we develop in this paper a flexible, intuitive technique that we call the double ABCD method. This method allows us to analyze and design spatially-chirped propagation systems. The propagation of the central axes of the Gaussian beamlets are first propagated as rays, either with paraxial ABCD matrices or non-paraxial tracing. The second step is to use ABCD matrices to propagate the Gaussian beamlets through the system as if they are traveling along the optical axis. Finally, the ray angles calculated from the raytrace are used to modify the expression for the Gaussian beam, thereby incorporating the phase information correctly. This method can accurately describe the spatio-temporal structure of propagating beams with spatial chirp. Kostenbauder [15] has developed an extension of ABCD matrices that accounts for spatio-temporal propagation that has been used to analyze dispersive systems (e.g. [16]. The Kostenbauder matrices provide a compact means to analyze systems to second order in the phase. The approach detailed here is more general since most of the computation is performed in frequency space where each ω–component can be considered to propagate independently. The aim of the double-ABCD technique is not so much to calculate the dispersion of pulse stretching/compression systems, for which there are other techniques [16–18], rather it is to aid in the understanding and design of systems that manipulate the spatial chirp of systems to control the spatio-temporal intensity distribution.

After an overview of optical systems that can be used to produce focusing spatially-chirped beams (Section 1.1), we provide a brief summary of the approach to describe the propagation by performing a direct Fresnel transform on the focusing, spatially-chirped beam (Section 1.2). In Section 2 we describe the propagation of beams in frequency (ω) space, since in linear propagation the spatial and frequency components can be considered as separable functions. As part of this analysis, we derive a general approach to starting with a field that has a known Fresnel propagation on-axis and modifying it to include the effects of tilting its propagation direction at an angle to the optical axis. The resulting expression is then used to analyze the pulse in the spatial and spectral domains. Finally, in Section 3 we investigate the structure of the pulse in the spatial/temporal domains, where we can obtain insight into the origins of the axial intensity localization and the scaling with the degree of spatial chirp.

1.1. Optical systems for simultaneous spatial and temporal focusing

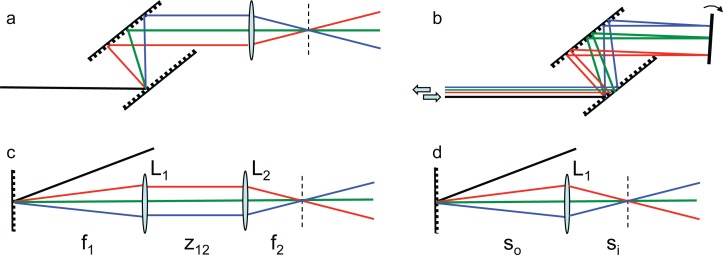

The principal goal in space-time focusing is to start with a beam in which the spectral components are spatially-dispersed, then form a focal plane where the spectral components overlap and the pulse is compressed. Directing a beam with lateral spatial chirp (parallel frequency components) into a lens or focusing mirror will cross the frequencies at the focal plane. There are several ways to produce this beam with lateral spatial chirp, some of which are shown in Fig. 1. The most straightforward method, used in our experiments [5, 6], is to employ a single-pass parallel grating compressor [Fig. 1(a)]. Note that the same amount of compression obtained in a conventional double-pass compressor can be obtained for a single-pass compressor by simply doubling the grating separation. In this case, the incoming chirped pulse is compressed at the output in the sense that there is no pulse front tilt, even though there is spatial chirp. It is well known that misalignment of a double-pass compressor will result in a spatially-chirped beam [1]. Adjusting the gratings out of parallel will result in angular spatial chirp; a beam will not generally come to a focus where the frequency components cross. However, if the retroreflection mirror is misaligned to use a different incident angle for the return beam [Fig. 1(b)], the output will have a (generally small) lateral spatial chirp.

Fig. 1.

Configurations for space-time focusing. a) Single-pass, parallel grating compressor. b) Double-pass compressor, but with retroreflection mirror tilted in the horizontal plane. c) Collimation of spectral components from single grating, refocus with second lens. d) Imaging of single grating to target.

Imaging optics can be used to generate spatially chirped beams with a single grating. In nonlinear microscopy experiments(e.g. Ref. [4]), a single grating is placed at the back focal plane of a lens (L1) and a second lens (L2) is placed near the front focal plane of L1, so that the beam waist is focused tightly [Fig. 1(c), with z12 = f1]. A similar configuration, with z12 = f1 + f2 produces an image of the grating at the focal plane of L2 [19]. In this case, the focused intensity is limited by the magnification of the system. Finally, one can image a spot on the grating to the sample with demagnification [Fig. 1(d)]. In such a system, the beam will not necessarily be at a focus where the wavelengths cross. A telescope to adjust the input divergence can be used to arrange for the beam and wavelength focii to overlap. Unlike the dual grating compressor arrangements, these imaging systems do not greatly affect the input chirp of the pulse.

In the schematics above, the wavelength components are propagated as rays through the system. Clearly this is not sufficient to describe the evolution of the field through the system. The principle applied in this paper is to separately calculate the beam propagation of each frequency component, then apply the information about beam direction and position calculated from a raytrace to result in a final expression for the field. This approach should greatly simplify the analysis of optical systems designed to manipulate spatially chirped beams.

1.2. Direct Fresnel spatio-temporal beam propagation

In free space, the wave equation is separable when the field is represented in the spatial and frequency domains. Each frequency component can be propagated independently of the others and the final result can be Fourier-transformed back to the time domain. The starting point for the spatial-chirp focusing problem is a beam of central frequency ω0 (and vacuum wavenumber k0 = ω0/c) propagating in the z direction, with the beam waist (1/e2 radius win) at the entrance of a lens of focal length f. Each frequency component is laterally shifted at the lens entrance by the distance α (ω − ω0), where α is a parameter that describes the spatial chirp rate:

| (1) |

The first term of the right-hand side represents the complex input spectrum, containing any input spectral phase ϕin.

Following Goodman [20], we can propagate this beam in the forward direction (z > 0) by taking the spatial Fourier transform of Eq. (1) multiplied by the lens phase factor exp [−ik0 (x2 + y2)/2f] to obtain the angular spectrum (with spatial frequency fx). The wavenumber is defined as k0 = ωn(ω)/c. To propagate the field, the angular spectrum is multiplied by the Fresnel propagation phase. An inverse transform back to position space yields the spatio-spectral field

| (2) |

For simplicity, we suppress the y-dependence of the field, since that component propagates independently as a Gaussian beam. Since the propagation phase is a function of ω through k0, each frequency component propagates independently.

With Gaussian functions, the spatial Fourier transforms in ω space can be performed analytically. Under the assumption of limited spectral bandwidth, Durst et al performed analytic inverse Fourier transform to the time domain [4]. Alternatively, the result can be sampled on a grid and numerically transformed to the time domain. While this approach is direct and conceptually straightforward, it is difficult to interpret the analytic form of the results and to generalize to other systems. The complication arises from the well-known result that a Gaussian beam with a waist at the entrance of a lens will not have its minimum waist at the lens focal plane, owing to the divergence of the input beam. Even though this effect may not be significant, it is present in the analytic form. Our approach, described in the next section, circumvents this problem by writing a form for the spatially-chirped beam so that the beam waists and the beamlet crossing planes coincide. This approach allows for further insight into the propagation effects.

2. Frequency-space analysis and Double ABCD propagation

Since linear propagation can be calculated separately for each frequency component, we can treat each of these components as a beamlet. Then we incorporate the frequency dependence of the angle and position of these beamlets to obtain information about the spatio-temporal structure.

2.1. Structure of the spatially-chirped input beam

As described in Section 1.2 the input Gaussian beam with lateral spatial chirp is given by Eq. (1). Note that the x–dependence of the field may be understood as a superposition of Gaussian beamlets of radius win that have a lateral shift α (ω − ω0) at the lens entrance. Since the actual extent of the beam size is related to the bandwidth of the input pulse, it is convenient to define two dimensionless parameters, the spatial chirp rate β, and the spatial chirp beam aspect ratio βBA. Since the 1/e2 half-width of the Gaussian input spectrum is Δω, αΔω corresponds the position of the frequency component ω0 + Δω at the lens entrance, which we express in terms of a factor β times the input beam width. The dimensionless spatial chirp rate is then

| (3) |

The spatially-chirped beam as it appears at the lens entrance is stretched in the direction of the spatial chirp and ideally takes the form of an elliptical Gaussian beam. Integrating the input intensity over the the spectrum yields the input energy fluence. This integral is essentially a convolution of the spatial spread of the spectrum with the input beam size. The ratio of the 1/e2 radii of this beam is the spatial chirp beam aspect ratio:

| (4) |

The spatial dispersion of the spectrum lengthens the input pulse duration. Expanding the exponents in Eq. (1) we obtain an expression that makes clear the local spectral content:

| (5) |

The local bandwidth is independent of position and is narrower by the factor βBA, which, assuming there is no input chirp, stretches the input pulse duration by this factor. The shift in the peak of the local spectrum seen in Eq. (5) is (x/win) .

2.2. Plane wave analysis: origin of pulse-front tilt in focus

One of the interesting aspects of space-time focusing is that the pulse front is tilted, potentially quite strongly, at the focus. This tilt is present even if there is no such tilt at the entrance of the focusing optic. The pulse front tilt has been measured experimentally by Coughlan et al. [8] with scanning spectral interferometry. The spatio-temporal pulse structure has also been manipulated with a spectral pulse shaper placed before the angularly dispersive optics [21,22]. Much of the space-time structure of focused spatially-chirped beams can be calculated in the spatio-spectral domain. The simplest illustration of this method is to consider the role of angular spatial chirp in the pulse structure of Gaussian beams with planar wavefronts. This is the case at the SSTF focus if the location of the focused beam waists coincides with the crossing plane of the frequency components. Assuming the pulse is compressed at the focus (ϕin = 0), an angular spectral sweep that is linear in frequency leads to a phase function

| (6) |

Here we follow the convention of Eq. (1) where beamlets with ω > ω0 are displaced to positions x > 0, leading to θ < 0. The pulse front tilt (PFT) is defined as the spatial variation of the temporal peak of the pulse, which for a pulse without odd orders of spectral phase, is equal to the group delay evaluated at the central frequency. Since all frequency components are overlapped at the focal point we can calculate the frequency derivative of the spatially-dependent spectral phase to get the group delay ϕ1 (x, ω), then evaluate the result at ω0:

| (7) |

The input beam [Eq. (1)] has the short-wavelength part of the spectrum at x > 0; in the focus it is this side that leads in the PFT. Clearly, the tilt of the pulse front originates directly from the dependence of the beamlet angle with ω. Departure from linearity in the angular chip can introduce curvature in the pulse front. Such a departure is expected in practical situations, since the angular dispersion of a diffraction grating is to first order linear in wavelength, not frequency. To estimate the magnitude of the PFT, we eliminate the focal length in Eq. (7) by using win = 2cf/(ω0w0), where w0 is the 1/e2 radius in intensity of the focused spot size. We can also make use of the definition of the dimensionless spatial chirp rate β [Eq. (3)] to substitute for α, and replace the bandwidth by the transform-limited pulse duration τ0 = 2/Δω. Simplifying, it is straightforward to show that the temporal shift of the pulse front is simply

| (8) |

Note that the PFT depends only on the spatial chirp rate at the lens entrance, independent of the focusing conditions. Evaluating the second derivative of Eq. (6) to obtain the spatial dependence of the group delay dispersion (chirp), ϕ2 (x), yields

| (9) |

The spatial dependence of ϕ2 shows that in addition to the PFT, the pulse develops a spectral chirp that increases away from the optical axis. The second expression in Eq. (9) is an estimate of the broadening at x = w0. Since the broadening roughly corresponds to β times the duration of an optical cycle, this chirping at the sides of the focus will be significant only if the pulse is extremely short. However, if the frequency crossing plane is arranged to be far from the beamlet waist position, this term could be much more important since the beam size at that position could be much larger than the beamlet waist size.

2.3. Tilt transformation of a forward propagated field

To calculate the form of the field away from the focus we can extend this analysis to account for the diffractive evolution of the Gaussian beamlets. We first calculate the positions and angles of rays of different wavelength through the system. This can be done through paraxial ABCD matrices or non-paraxial tracing. Separately, we propagate the Gaussian beamlets through the system as if they are traveling along the optical axis. This gives the evolution of the beam sizes and wavefronts. To correctly combine the two, we need to transform a known field as it propagates on-axis to one that is propagating at an angle to the axis.

We start with an expression for an initial field (a beamlet with a specific frequency ω) that is propagating along the optical axis of the system (the z-axis). We can use the Fresnel integral to find the field at any position downstream. Consider next the same beamlet tilted at z = 0 at an angle θx to the z-axis by applying a linear phase ramp. This tilt can come from a prism, a grating, or from propagation off-center through a lens. The linear phase ramp in position space can be written as exp[ikxx], where kx = (ω/c)sinθx ≡ 2πfx0. We next calculate the tilted field in terms of the on-axis Fresnel-propagated field.

When the initial field is represented in the angular-spectral domain (through a Fourier transform [20]), the phase ramp produces a shift in the angular spectrum of the original field, Ẽ (fx − fx0, 0). To propagate the field, we multiply this by the non-paraxial propagator:

| (10) |

The square root may be expanded in two ways: around the new beam direction (fx = fx0) and around the original z-axis (fx = 0). The first expansion is more general, in that the beam direction change can be large, but the spread of the angular spectrum is small. The second expansion assumes that all angles are small: this corresponds to a direct Fresnel transform of the shifted field.

We treat first the more general case, where we do not assume that new angle of the beamlet to the z-axis is not necessarily small. In this case, we change variables to f′x = fx − fx0. Then, noting that the projection of the k-vector on the z-axis is defined through , we pull kz out of the square root and expand for 2πf′x/kz ≪ 1:

| (11) |

The tan θx term in the exponential results from the ratio 2πfx0/kz = kx/kz. To transform back to position space, we use the shift theorem to represent the result in terms of a transform with respect to f′x, with the result

| (12) |

Comparing to Eq. (2), we can see that the exponential quadratic in f′x is the Fresnel propagator, and the term linear in f′x will result in a shift in x. From this we conclude that we calculate the Fresnel propagation of the field without the phase ramp, then make the two substitutions

| (13) |

so that the propagation phase in front of the expression is exp[i(kxx + kzz)] instead of exp [ik0z]. This derivation is a result that can be applied to general diffractive propagation, though in this paper we will restrict our attention to the propagation of angled Gaussian beams. Note that the substitution of kz for k0 in this derivation applies globally throughout the expression for the Fresnel-propagated field without the phase ramp. In the context of Gaussian beams, this modification will change the Rayleigh range of the beam in the expressions for the z-dependence of the beam size, radius of curvature and the Gouy phase.

In the other limit where the beamlet angle is considered to be small, i.e. 2πfx/k0 ≪ 1. Note that this is implicitly assumed when the direct Fresnel transform described in Sect. 1.2 is performed. In this case, we expand the square root in Eq. (10) as is customary for Fresnel propagation. The propagated field takes the form

| (14) |

where k′z = k0 (1 − sin2θx/2). The tilt transformation is simpler in this case, since there is no global change to k0 and only the x coordinate is shifted:

| (15) |

This is the form of the tilt transformation that will be used above in calculating the spatio-temporal propagation of spatially-chirped beams.

2.4. Angled Gaussian beam propagation

In this section we apply these results to derive an expression for a tilted Gaussian beam that has a well-defined frequency ω. For a coordinate system centered on the beam waist, the Gaussian beam can be written in term of the amplitude and phase E (x,y,z,ω) = A(x,y,z,ω)exp[iϕ (x,y,z,ω)]. Using the sign convention that a forward-propagating plane wave is written as exp[i(k0z − ωt)], the well-known expression for the field is given by

| (16) |

where the beam radius (w), radius of curvature (R) and the Gouy phase (η) are given by

| (17) |

Note that w, R and η are implicitly functions of k0 (and ω) through the Rayleigh range .

We will assume that the beam tilt angle θx is small so that we can use the transform described in Eqs. (14) and (15). To perform the tilt transformation on the Gaussian beamlet, the amplitude function undergoes the shift in the x variable, x → x − zsinθx.

| (18) |

The phase structure is important for the analysis of the pulse shape throughout the focus. For the paraxial case,

| (19) |

This gives the complex field for a single-frequency Gaussian beam propagating at a specific angle to the optical axis. In an optical system that includes angular dispersion, we can obtain the beamlet angles from raytracing.

2.5. Combining raytracing with angled Gaussian beam propagation to obtain 3-D field

To look at the structure of the beam throughout its propagation, we include in our expression for an individual tilted Gaussian beam [Eqs. (18) and (19)] the frequency-dependence of the angle: θx = α(ω − ω0)/f. We then can expand spectral phase around ω0 to find the position-dependent group delay and chirp. Note that even though this paraxial treatment of the spatial chirp does not result in any angular dependence of the Rayleigh range, the Rayleigh range itself depends on frequency. If the focal spot size is considered to be frequency-independent, zR ∝ ω. However, if the beam size at the lens entrance is independent of frequency, then the focused spot radius is inversely proportional to frequency, and zR ∝ 1/ω. To focus on the primary effects of the spatial chirp, we hold zR constant, treating the frequency-dependence of the Rayleigh range as a higher-order effect that is appreciable only for extremely wide bandwidth pulses. The framework presented below can be extended in a straightforward way to the more general cases.

Expanding to first order the spectral phase of Eq. (19) with the frequency-dependent angular chirp, we obtain the position-dependent group delay:

| (20) |

The first term is just the arrival time of the pulse, and the last term, which is present even without spatial chirp, represents a pulse front curvature that results from the divergence of the beam away from the focal plane. The middle term corresponds to the PFT. When Eq. (20) is evaluated at the focus, z = 0, the PFT reduces to what we found earlier in Eq. (7). To better understand the z–dependence of the PFT, we can simplify the Gaussian beam radius of curvature R(z) using Eq. (17). We can also make use of the simplifications leading to Eq. (8) to obtain the more intuitive form:

| (21) |

The PFT is approximately zero far from the focus and develops within the beamlet confocal parameter. The magnitude of the PFT is directly proportional to the dimensionless chirp rate β.

Next we can expand to second order in the spectral phase to obtain the spatial dependence of the pulse chirp.

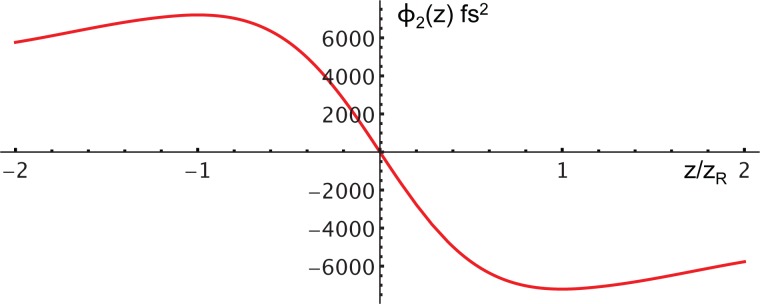

| (22) |

The x-dependent chirp is the extension of the result that we found for the focal plane, Eq. (9). This term, which is small for low bandwidth pulses, decreases away from the focal plane just as the PFT does [see Eq. (21)]. The z-dependent term in the first parenthesis is a new term that is important for the intensity localization of the spatio-temporal focus. This term is plotted in Fig. 2 for a value of β = 10. Even though the pulse is ideally perfectly compressed at the focal plane, it develops chirp at either side of the focus. This tends to increase the duration of the pulse away from the focal plane.

Fig. 2.

Dependence of geometric second-order chirp (ϕ2) on axial position.

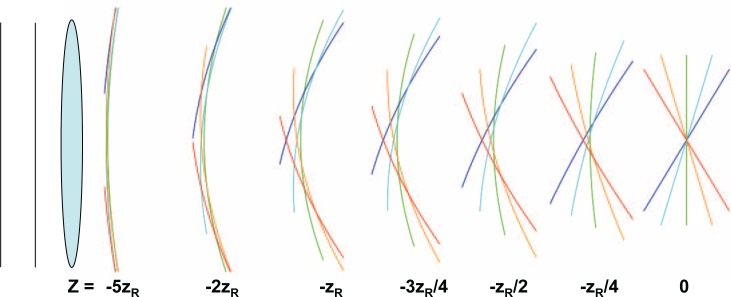

The on-axis spectral chirp originates from the geometry of the beamlet wavefront evolution through the focus. The calculated expressions of the spatio-spectral phase contain the information on the wavefronts of the individual Gaussian beamlets. Note that this information is not easily available in a direct Fresnel calculation. In Fig. 3 we show the evolution of the wavefronts of several beamlets of equally-spaced frequency. These are contours of constant phase, with the curvature of the wavefronts magnified to easier visibility. The position farthest to the left corresponds to a plane near the lens, where the wavefronts overlap to share the common phase front imparted by the lens. As the beam approaches the focus, the curvature of the individual beam-lets increases, then flattens at the focus. Along the z-axis, there is initally no variation in the phase with frequency, but a phase offset develops closer to the focus. From the wavefront spacing, it can be seen that the variation in phase is in fact predominately parabolic in frequency, indicating a linear frequency chirp. The pulse chirp reaches a maximum at one Rayleigh length from the focus (see also Fig. 2). At the focus, the individual wavefronts are flat and there is no chirp there, as the wavefronts are coincident along the z-axis. On the other side of the focal plane, the chirp has the opposite sign. This progression of the wavefronts arises because of the independent propagation of the individual Gaussian beamlets.

Fig. 3.

Evolution of beam wavefronts from a point relatively close to the lens (left side) toward the focal plane at z = 0. Each colored wavefront corresponds to a particular frequency beamlet.

We have also calculated the third-order phase ϕ3(x, z), and we find that it follows the same x- and z-dependence as ϕ2(x, z), but with a leading factor of 1/ω0. Therefore, if the expansion terms are assembled into a Taylor series, the contribution of the third-order to the net phase is smaller than that from the second-order by the factor (ω − ω0)/ω0. The geometric third-order phase is important only for large-bandwidth pulses; it will generally add to the increase of the pulse duration away from the focal plane.

3. The structure of space-time focused beams

The preceding analysis in the spatio-spectral domain provides a great deal of insight to the structure of the pulse and the beam through the focus. One of the principal applications of this technique is that the axial intensity can be localized very strongly by the space-time focusing. To calculate the intensity, we must transform our field into the time domain. Doing so provides further insight into the how the intensity localization is achieved.

3.1. Calculation of the spatio-temporal field

The expressions for the field in Eqs. (18) and (19), with the ω–dependence of the beamlet angle θx depend in a non-trivial way on ω. The direct Fourier transform cannot be calculated analytically, but we can make use of the analysis above to expand the spectral phase to second-order in the frequency difference. Provided we ignore the frequency-dependence of the Rayleigh range, the amplitude functions are Gaussian functions, and analytic transform is possible. In order to do so, it is important to rearrange the expression for the spectral amplitude [Eq. (18)] so that the local bandwidth and center frequency is clear. We assume an input Gaussian spectrum with 1/e amplitude half-width Δω. By expanding the frequency-dependent angular terms in Eq. (18) and simplification, the amplitude function can be expressed in the simple form:

| (23) |

The auxiliary z-dependent functions defined in this expression are best represented in terms of the dimensionless variable ζ = z/zR. The x-dependent beam radius is defined through

| (24) |

and the local center frequency and the local bandwidth are

| (25) |

| (26) |

Note that the local bandwidth is independent of the transverse coordinate. Although the local pulse duration is determined both by the local bandwidth and the degree of chirp, it is instructive to calculate the local bandwidth-limited pulse duration:

| (27) |

At large distance from the focal plane, ζ ≫ 1, we find the pulse duration is longer than the transform-limited pulse duration by the factor βBA. Thus βBA is the pulse duration contrast that we obtain from spatial-chirp focusing.

To evaluate the field in the time domain, we assemble the calculated spectral amplitude and phase components we have calculated thus far:

| (28) |

Before we focus our attention on the on-axis temporal intensity, we make a comment about the calculation of the 3-D field. Note that the local central frequency ωL is shifted away from ω0 when x ≠ 0. After calculating the inverse Fourier transform, this shift in center frequency does not affect the local pulse duration (since ΔωL is independent of x). However, it does result in a group delay offset. This offset adds to the group delay ϕ1 that was calculated from the expansion of the spectral phase around ω0. This shift affects the detailed structure of the PFT off-axis and away from the frequency crossing plane.

For x = 0, ωL = ω0, we can use the second-order phase from Eq. (22), perform the inverse Fourier transform. If there is no input spectral chirp, the local pulse duration reduces to

| (29) |

With an input chirp of ϕ2in, the local on-axis pulse duration has a considerably more complicated form:

| (30) |

Note that the input chirp can compensate the geometric phase over a narrow range (see Fig. 2). Within that range, the argument of the square root in Eq. (30) goes to unity, and the pulse duration goes to the bandwidth-limited value at the z-position where the chirp cancellation takes place.

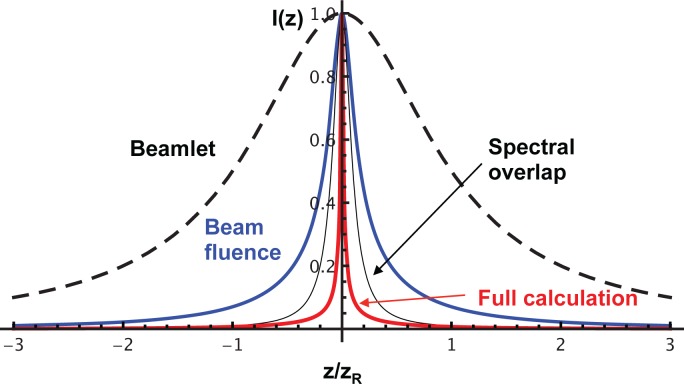

3.2. Contributions to the axial localization of the temporal intensity

The analytical technique here allows for insight to the origins of the different contributions to the axial localization for this focused spatially chirped beam (Fig. 4). In this figure, the dashed line shows the energy fluence profile for a single Gaussian beamlet: ∝ Ein/[πw2 (z)]. The other curves shown account for successively more of the localization contributions. The second widest curve shows the effect of focusing at a higher numerical aperture in the spatially-chirped direction. The beam fluence, ∝ Ein/[πwx (z) w(z)], is lower away from the focal plane relative the the single beamlet. In the simplest view of space-time focusing, the increase in the pulse duration away from the focus results from the decrease of the local spectral width. The third widest curve accounts the decrease in the local bandwidth away from the focus [Eq. (27)], but neglects the geometric chirp. This axial intensity profile is further reduced by the geometric spectral chirp that is present within the confocal parameter of the focus [Eq. (29)] (center curve).

Fig. 4.

Contributions to axial intensity localization. The outer dashed line corresponds to the axial intensity for the non-spatially-chirped beamlet. The next line in (blue) accounts only for the change in beam fluence that arises from spreading the beam at the lens in the x-direction. When the on-axis spectral width is calculated, the minimum possible pulse duration is increased away from the focus, resulting in the third curve (black, solid). The full Fresnel calculation shows further localization resulting from the geometric chirp (red).

When the contributions to the axial dependence of the intensity are multiplied, we can obtain a simple expression for the axial intensity profile:

| (31) |

where I0 is the peak intensity at the focus. In the limit of no spatial chirp, βBA → 1, and the intensity follows the Lorentzian profile of a conventionally-focused Gaussian beam.

Equation (31) for the axial intensity assumes a perfectly-aligned optical system. There are several degrees of freedom that must be aligned to achieve the maximal axial localization. As noted above, input chirp (ϕ2in) can combine with the geometric chirp to shift the plane at which the pulse is compressed. This feature of space-time focusing has been used to scan the focal plane along the z-axis [2, 11]. The analysis above clearly shows that while the plane where ϕ2 = 0 can be moved throughout the confocal parameter (see Fig. 2), the peak intensity and the localization suffer because the plane of zero chirp is moved to a position where the different frequency beamlets are not fully overlapped. (see Fig. 5(a)). The pulse duration is longer even though there is no spectral chirp because it is limited by the local bandwidth [Eq. (27)]. The increase in the beam area away from the wavelength crossing plane also decreases the peak intensity. The axial tuning is illustrated in Fig. 5(a).

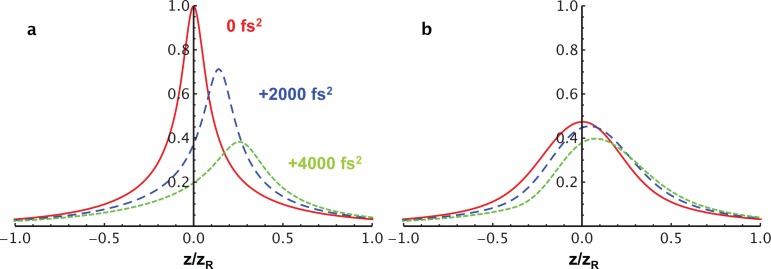

Fig. 5.

Variation of the axial intensity with input spectral chirp (ϕ2) for a beam focused with a beam aspect ratio of βBA = 4 and a transform-limited pulse duration of 40 fs. In both graphs, the second-order phases are ϕ2 = 0 (red), ϕ2 = 2000 fs2 (blue), ϕ2 = 4000 fs2 (green). (a) No input third-order phase. (b) Positive input ϕ3 = 2 × 105 fs3

Figure 5(b) shows the variation of the axial intensity profile with input second-order phase for the case where there is strong additional third-order phase. Such a situation can arise in the alignment of a single-pass compressor with incident angle that is imperfectly optimized. For all of the curves, the pulse duration is longer because of the third-order phase, and it is seen that the addition of second-order phase does not further change the pulse duration significantly. The position of the peak intensity does not move as much as when the third-order phase is not present. A pulse with strong third-order has an Airy shape, which is known to have little sensitivity to second-order dispersive phase [23]. In an experimental configuration, lack of axial tuning of the high intensity position can be a sign of excessive third-order phase.

4. Discussion: scaling analysis of space-time focused beams

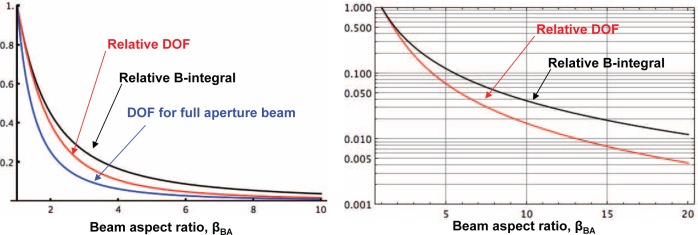

The depth of focus of the spatially-chirped focus can be defined as the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the axial profile in Eq. (31). We can find a closed-form solution for the depth of focus, ζDOF :

| (32) |

The value of the depth of focus for the spatially-chirped beam, relative to the depth of focus of the non-spatially-chirped focused beamlet is plotted as a dotted line in Fig. 6. A factor of 10 decrease in ζDOF is obtained at a beam aspect ratio of βBA ≈ 4.1. It is important to observe that the beam aspect ratio is the sole parameter that controls the decrease of the depth of focus over the Gaussian beam limit. Therefore, the same localization can be obtained with ps-duration pulses as with fs pulses, provided the optical system produces sufficient spatial chirp for the desired value of βBA. Coherence is required, however: a broadband ns Q-switched pulse would not be increased by spreading the spectrum out spatially. The geometric spectral chirp effects described above would not lengthen the pulse duration away from the focus because such lengthening requires spectral phase coherence.

Fig. 6.

Depth of focus (DOF) and B-integral through focus as a function of the beam aspect ratio, for linear (a) and log (b). Dashed curve in (a) indicates the effective decrease in the DOF for a conventional Gaussian beam focus for a beam that uses the full aperture of the lens.

In principle, it is possible to obtain localization by focusing a multimode beam. The quantity M2 is often used to characterize aberrated beams [24]. As the multimode content increases, the value of M2 increases, and for a given spot size, the effective Rayleigh range is decreased by the M2 factor. Therefore the effective depth of focus can be reduced by creating a beam with a wide distribution of transverse spatial modes. However, such a beam would require each mode must be correctly phased with all the others at the focus. Conventional ways to produce multimode beams, with random phase plates or by coupling the beam into a multimode fiber, would leave each mode with a different phase, effectively reducing the coherence of the beam.

When the spatially-chirped beam enters the final focusing optic, the elliptical beam occupies a larger aperture than the non-spatially-chirped beam by the factor ζDOF. It is instructive to compare the depth of focus that can be attained by filling the aperture of the optic with a larger beam. If one increases the beam size entering a lens of a fixed focal length by a factor n, the spot size decreases by 1/n and the confocal parameter increases by n2. Since the spatially-chirped beam requires a larger aperture than the beamlet by the factor βBA, we can plot as a reference the curve to represent the relative decrease in the depth of focus by filling the lens. This line, shown as a dashed line in Fig. 6(a), is always below that of the spatially-chirped focus (dotted line); in fact, in the limit of large spatial chirp, the ratio approaches . Although localization using spatial chirp is not as great as it is for a conventionally-focused beam that fills the lens, the focal spot is larger when the spatial chirp is used. In micromachining, for example, a larger spot allows much more rapid machining. As we will see below, the spatial chirp focus also allows the focal volume to approach a spherical shape.

One of the most important features of space-time focusing is that the intensity is much lower than usual as the beam approaches the focal plane. This leads to a dramatic reduction in self-focusing, allowing much higher intensity to be reached in a bulk material [5]. Self-focusing arises from the accumulation of nonlinear phase ϕNL = ∫k0n2I (z) dz through the medium with nonlinear refractive index, n2 (e.g. see [25]). To evaluate how the spatial chirp affects this nonlinear interaction, we can calculate ϕNL by integrating over the complete unperturbed axial intensity profile for the cases with and without spatial chirp. In Figs. 6(a) and 6(b), the ratio of these two integrals, the relative B-integral is shown as a solid curve. To reduce the B-integral by a factor of 10, for example, we can use βBA ≈ 5.5. It is well known that for a Gaussian beam the threshold for self-focusing depends on the peak power, not the peak intensity: in the tight-focusing limit, where the nonlinear medium extends beyond the Rayleigh range to either side of the focal plane, a smaller focal spot leads to higher intensity but also a shorter interaction length (2zR). With space-time focusing, it is possible to decrease the interaction length (the depth of focus, Eq. (32)), which leads to an increased threshold for self-focusing. For the same reason, space-time focusing can reduce the effects of ionization defocusing.

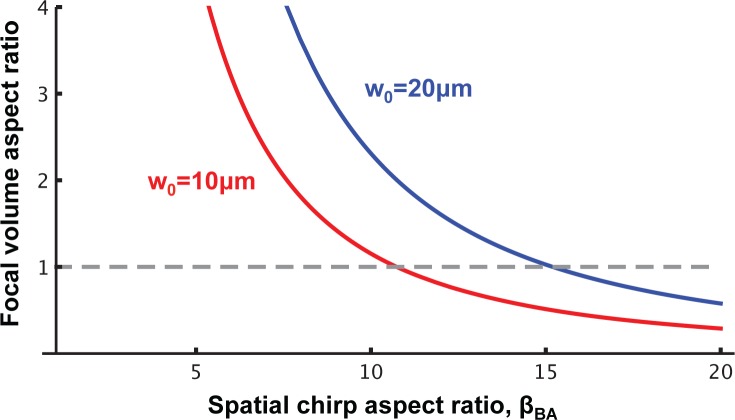

Since the degree of localization increases with the spatial chirp aspect ratio, it is possible to control the shape of the focal volume. He et al. [7,26] have fabricated waveguides in glass with a circular cross-section using this technique. For a conventional Gaussian beam, we may define the aspect ratio of the focal volume ρG as the confocal parameter divided by the FWHM of the focal spot:

| (33) |

where n is the refractive index in the medium. It is difficult to obtain ρG = 1 with conventional focusing. Even if the beam is focused at F/1, ρG = 3.4. Figure 7 shows the focal volume aspect ratio for the spatial chirp focusing case. The beam aspect ratio for which ρST = 1 is at the value of βBA where the curves cross the dotted line. Creating a spherical focal volume requires larger spatial chirp as the spot size is increased. For w0 = 10μm, ρST = 1 at βBA ≈ 11 (solid line); for w0 = 20μm a beam aspect ratio of βBA ≈ 15 is required (dashed line).

Fig. 7.

Calculation of the spatial chirp dependence of aspect ratio of the focal volume as the ratio of the longitudinal intensity FWHM to the transverse intensity FWHM for two different focal spot sizes. Dashed line indicates the point where the focal volume is approximately spherical.

5. Summary

Using the concept of extending Gaussian beam propagation to include a frequency-dependent angle of propagation, we have developed an intuitive theory for linear spatio-temporal propagation of ultrafast pulses. The approach allows us to treat each frequency component as its own Gaussian beamlet. The axis of the beamlet can be traced through an optical system geometrically, either using ABCD matrices or by using a raytracing program. The evolution of the Gaussian beamlet can also be calculated separately using the ABCD method. Finally, the angle and displacement information of the beamlet axis from the ray trace is incorporated into the phase and amplitude structure of the spatio-spectral field. As shown above, much information about the pulse front tilt and the frequency chirp of the pulse can be obtained from the spatio-spectral field. Fourier transformation to the time domain gives the intensity profiles. This allows us to understand the contributions to the axial localization of the intensity in the ideal space-time focusing configuration in which the beamlet waist position and the frequency crossing plane coincide. In later work, we will explore more general cases and spatial chirp systems using this double ABCD approach. Nonlinear interactions such as harmonic- [19] and sum-frequency generation [27] have been investigated. We are currently investigating the nonlinear propagation effects such as self-focusing and ionization defocusing of space-time focused beams.

Acknowledgments

C.D. and J.S. acknowledge funding support from AFOSR under grants FA9550-10-1-0394 and FA9550-10-0561. J.S. acknowledges support from NIH grant EB003832. E. Block acknowledges support from the NSF under DBI-0852868.

References and links

- 1.Osvay K., Kovacs A. P., Heiner Z., Kurdi G., Klebniczki J., Csatari M., “Angular dispersion and temporal change of femtosecond pulses from misaligned pulse compressors,” IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 10, 213–220 (2004). 10.1109/JSTQE.2003.822917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oron D., Tal E., Silberberg Y., “Scanningless depth-resolved microscopy,” Opt Express 13, 1468–1476 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.001468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu G., van Howe J., Durst M., Zipfel W., Xu C., “Simultaneous spatial and temporal focusing of femtosecond pulses,” Opt. Express 13, 2153–2159 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.002153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durst M., Zhu G., Xu C., “Simultaneous spatial and temporal focusing in nonlinear microscopy,” Opt. Commun. 281, 1796–1805 (2008). 10.1016/j.optcom.2007.05.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitek D. N., Adams D. E., Johnson A., Tsai P. S., Backus S., Durfee C. G., Kleinfeld D., Squier J. A., “Temporally focused femtosecond laser pulses for low numerical aperture micromachining through optically transparent materials,” Opt. Express 18, 18086–18094 (2010). 10.1364/OE.18.018086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitek D. N., Block E., Bellouard Y., Adams D. E., Backus S., Kleinfeld D., Durfee C. G., Squier J. A., “Spatio-temporally focused femtosecond laser pulses for nonreciprocal writing in optically transparent materials,” Opt. Express 18, 24673–24678 (2010). 10.1364/OE.18.024673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He F., Xu H., Cheng Y., Ni J., Xiong H., Xu Z., Sugioka K., Midorikawa K., “Fabrication of microfluidic channels with a circular cross section using spatiotemporally focused femtosecond laser pulses,” Opt. Lett. 35, 1106–1108 (2010). 10.1364/OL.35.001106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coughlan M., Plewicki M., Levis R., “Parametric spatio-temporal control of focusing laser pulses,” Opt. Express 17, 15808–15820 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.015808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazansky P. G., Yang W., Bricchi E., Bovatsek J., Arai A., Shimotsuma Y., Miura K., Hirao K., ““Quill” writing with ultrashort light pulses in transparent materials,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 151120 (2007). 10.1063/1.2722240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang W., Kazansky P. G., Shimotsuma Y., Sakakura M., Miura K., Hirao K., “Ultrashort-pulse laser calligraphy,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 171109 (2008). 10.1063/1.3010375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durst M., Zhu G., Xu C., “Simultaneous spatial and temporal focusing for axial scanning,” Opt. Express 14, 12243–12254 (2006). 10.1364/OE.14.012243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmer D., Ros D., Guilbaud O., Habib J., Kazamias S., Zielbauer B., Bagnoud V., Ecker B., Hochhaus D., Aurand B., “Short-wavelength soft-x-ray laser pumped in double-pulse single-beam non-normal incidence,” Phys. Rev. A 82, 013803 (2010). 10.1103/PhysRevA.82.013803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez O. E., “Achromatic phase matching for second harmonic generation of femtosecond pulses,” IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 25, 2464–2468 (1989). 10.1109/3.40630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fueloep J. A., Palfalvi L., Hoffmann M. C., Hebling J., “Towards generation of mJ-level ultrashort THz pulses by optical rectification,” Opt. Express 19, 15090–15097 (2011). 10.1364/OE.19.015090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kostenbauder A. G., “Ray-pulse matrices: a rational treatment for dispersive optical systems,” IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 26, 1148–1157 (1990). 10.1109/3.108113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chauhan V., Cohen J., Trebino R., “Simple dispersion law for arbitrary sequences of dispersive optics,” Appl. Opt. 49, 6840–6844 (2010). 10.1364/AO.49.006840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Druon F., Hanna M., Lucas-Leclin G., Zaouter Y., Papadopoulos D., Georges P., “Simple and general method to calculate the dispersion properties of complex and aberrated stretchers-compressors,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 25, 754–762 (2008). 10.1364/JOSAB.25.000754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durfee C. G., Squier J., Kane S., “A modular approach to the analytic calculation of spectral phase for grisms and other refractive/diffractive structures,” Opt Express 16, 18,004–18,016 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.018004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oron D., Silberberg Y., “Harmonic generation with temporally focused ultrashort pulses,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 22, 2660–2663 (2005). 10.1364/JOSAB.22.002660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman J., Introduction to Fourier Optics, 3rd ed. (Roberts and Company Publishers, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oron D., Silberberg Y., “Spatiotemporal coherent control using shaped, temporally focused pulses,” Opt. Express 13, 9903–9908 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.009903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coughlan M., Plewicki M., Levis R., “Spatio-temporal and-spectral coupling of shaped laser pulses in a focusing geometry,” Opt. Express 18, 23973–23986 (2010). 10.1364/OE.18.023973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong A., Renninger W. H., Christodoulides D. N., Wise F. W., “Airy–Bessel wave packets as versatile linear light bullets,” Nat. Photon. 4, 103–106 (2010). 10.1038/nphoton.2009.264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegman A. E., Lasers, 1st ed. (University Science Books, 1986). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyd R. W., Nonlinear Optics, 3rd ed. (Academic Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 26.He F., Cheng Y., Lin J., Ni J., Xu Z., Sugioka K., Midorikawa K., “Independent control of aspect ratios in the axial and lateral cross sections of a focal spot for three-dimensional femtosecond laser micromachining,” New J. Phys. 13, 083014 (2011). 10.1088/1367-2630/13/8/083014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durst M., Straub A., Xu C., “Enhanced axial confinement of sum-frequency generation in a temporal focusing setup,” Opt. Lett. 34, 1786–1788 (2009). 10.1364/OL.34.001786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]