Abstract

The promise of widespread implementation of efficacious interventions across the cancer continuum into routine practice and policy has yet to be realized. Multilevel influences, such as communities and families surrounding patients or health-care policies and organizations surrounding provider teams, may determine whether effective interventions are successfully implemented. Greater recognition of the importance of these influences in advancing (or hindering) the impact of single-level interventions has motivated the design and testing of multilevel interventions designed to address them. However, implementing research evidence from single- or multilevel interventions into sustainable routine practice and policy presents substantive challenges. Furthermore, relatively few multilevel interventions have been conducted along the cancer care continuum, and fewer still have been implemented, disseminated, or sustained in practice. The purpose of this chapter is, therefore, to illustrate and examine the concepts underlying the implementation and spread of multilevel interventions into routine practice and policy. We accomplish this goal by using a series of cancer and noncancer examples that have been successfully implemented and, in some cases, spread widely. Key concepts across these examples include the importance of phased implementation, recognizing the need for pilot testing, explicit engagement of key stakeholders within and between each intervention level; visible and consistent leadership and organizational support, including financial and human resources; better understanding of the policy context, fiscal climate, and incentives underlying implementation; explication of handoffs from researchers to accountable individuals within and across levels; ample integration of multilevel theories guiding implementation and evaluation; and strategies for long-term monitoring and sustainability.

Most scientific evidence about improving health and health care stems from single-site and single-level interventions, taking decades to move from clinical trials to new routines at bedsides or clinic offices (1,2). Despite the growing volume of such interventions in the literature, their application in typical practice settings remains stubbornly elusive, rendering the promise of evidence-based practice—widespread implementation of efficacious interventions into routine clinical care—still unrealized (3,4). Also, few interventions address interventions outside health-care settings, limiting potential contributions of community-level interventions to advances in public health (eg, mobile units, neighborhood screening). The heart of the matter, however, is that the evidence itself is insufficient, as single-level interventions have chiefly been tested under highly-controlled and homogenized circumstances, often in academic medical centers or other settings—circumstances unlike those in which most patients obtain their care (5,6). As a result, interventions yielding significant advances under controlled research protocols undergo what has been described as a “voltage drop” when applied to real-world settings (7).

Applying the current state of research evidence to health care (ie, fostering the adoption, implementation, spread, and sustainability of new evidence-based approaches to care) requires explicit attention to the interactions between and among multiple levels of influence surrounding any particular single-level intervention (ie, communities and families surrounding patients; health-care policies and organizations surrounding provider teams) (8,9). Indeed, practice guidelines have increasingly embraced multilevel concepts (eg, tobacco control guidelines incorporate patient-, provider-, and system-level recommendations) (10,11), though rarely based on trials that themselves were multilevel (12,13).

Though seldom reported (14), the contextual influences underlying intervention success (or failure) have been the subject of increasing study, as each contextual layer potentially becomes the target for additional intervention components (15–19). Greater recognition of such influences has motivated the design and testing of multilevel interventions that target them (20,21). However, relatively few multilevel interventions (comprising ≥3 levels) have been conducted along the cancer care continuum, and fewer still have been implemented, spread, or sustained in practice (20).

The purpose of this chapter is to illustrate and examine the concepts underlying the implementation and spread of predominantly single-level interventions into the multilevel context of routine practice and policy using a series of cancer and noncancer examples. The examples span different levels and stages of the care continuum, from community-based primary prevention to screening in diverse clinical practices to treatment implementation and spread in large integrated health-care systems.

Implementation and Spread of Interventions Into the Multilevel Context of Routine Practice and Policy

Efficacy vs Effectiveness: Getting to Implementation

Efficacy studies place primary emphasis on internal validity to maximize the certainty with which claims may be made that the intervention was responsible for the observed differences in outcomes. Effectiveness (and implementation) studies must generalize from efficacy studies, recognizing all the ways in which they lack external validity and particular relevance to the local circumstances in which they would be applied and necessarily adapted (22) (Table 1). Adaptations require setting-specific evaluations as efficacy studies provide no assurance that the adaptations will achieve the same effects in different settings, circumstances, populations, cultures, and political environments (23). These differences account for much of the diminished impact when interventions from efficacy trials are implemented more broadly.

Table 1.

Issues of efficacy vs effectiveness related to implementation of interventions into the multilevel context of routine practice and policy*

| Multilevel intervention considerations | Efficacy | Effectiveness |

| Personnel | Carefully selected, trained, and supervised in their behavior as interventionists Little discretion permitted in their deviation from the experimental protocol |

Usually not as dedicated to the intervention (one of many responsibilities) Level of training, supervision, and protocol-adherence varies |

| Financing and time allocation | Research grant–supported intervention provides for greater and more dependable resource allocation/dedication in time and funding | Grant support rarely covers dedicated time/effort in nonacademic practice settings Significant competing demands for time and attention |

| Diversity of patients | Focus on carefully considered inclusion and exclusion criteria Restricts exposure to those most likely to benefit Exclusion criteria and attrition in highly controlled trials skews distribution of patient characteristics to a more unrepresentative sample from which to infer applicability of intervention elsewhere |

Applied to patients with greater diversity and heterogeneity Higher external validity but with greater variability in effect Subgroup analyses are important for evaluating differential effects but are usually omitted because subgroups were not randomized Subgroup analyses enable better judgments about relevance and applicability of findings for different types of patients in different settings Advance consideration in sampling and stratification needed to ensure adequate subgroup sample sizes |

| Diversity/mix of providers | May focus on a very small number of providers (even n = 1) Provider qualifications may be specific to setting (ie, skill-mix unique to large tertiary care academic medical center) May represent willing colleagues with established relationships |

Greater diversity of provider training, experience, and skill Higher external validity but with greater variability in effect May require adding training and other provider behavior change components Should include provider-level measurements |

| Diversity of practices or organizations | Commonly one or more selected academic medical centers (rarely if ever randomly drawn) May include principal investigator’s institution, potentially conferring unusual degree of influence/control |

If retain focus on academic centers, may draw from diverse geographic regions and locations (eg, urban/rural) May require additional training and other organizational behavior change components Likely to require site investigators and provider behavior change components relevant to local context Should include practice and/or organizational level measurements Use of one or more PBRN increases external validity |

| Diversity of community/area | Tends to reflect large urban areas | Still tend to reflect larger urban areas but may stratify by region, location, or other area characteristics (eg, health-care resources, sociodemographic mix) |

| Unintended consequences of study procedures | Informed consent and testing procedures limit generalizability to settings/applications where these procedures would not be linked to the intervention | Consent and testing procedures commonly still in place May influence sample representativeness at multiple levels (ie, inability to assess effectiveness in sites without an IRB if conducting research) |

*IRB = institutional review board; PBRN = practice-based research network.

Implementation and spread are neither direct nor intuitive when patients are selected to reduce complexity, when interventions are tested only in the most favorable environments, when context is factored out, and when researchers work to ensure strict protocol adherence and control (that will not typically be feasible during implementation in other sites/levels). Rather than being entirely controlled by researchers, interventions implemented in real-world settings must involve and engage policymakers, managers, providers, nurses, clerks, and usually patients and their families, as key stakeholders in the new processes underlying implementation at each level. These stakeholders are directly engaged in working to determine how to adapt intervention elements to their practice and routines and within their social norms and settings (ie, their context). Researchers’ capacity to influence such adoption is acutely determined by the nature of the “handoffs” and support they construct through negotiation with the people, places, and circumstances of each environment they seek to improve. Each aspect of change (for stakeholders at each level), therefore, requires consideration of how individuals contribute to (or hinder) implementation. To further spread interventions to achieve a universal and permanent new way of doing business, new organizational units and/or fiscal policies may be required or new legislation enacted (24).

Furthermore, not all contextual factors are modifiable, requiring adaptation that stretches beyond the available evidence base (eg, urbanization, family structure) and commonly beyond investigators’ comfort zones (18). As adaptation extends to less familiar levels in which investigators have less influence, the inevitable drift from the seeming simplicity of the original evidence bases to accommodate increasingly diverse practices and communities complicates virtually everything (5,25). Hawe et al. (26) recommend, instead, starting with an understanding of the community first and studying how phenomena are reproduced in that system, rather than focusing on mimicking processes from the original controlled setting. Either way, it is essential to bridge the gaps between evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence (27).

Theoretical Foundations for Implementation and Spread

Much of the research evaluating implementation of interventions in real-world settings has lacked strong theoretical foundations, thereby ignoring the contributions of different social science disciplines to their design and implementation (28,29). While theoretical frameworks represent an important resource for designing implementation efforts (30–32), no integrative theories have been developed to specifically guide implementation across multiple levels. Designing effective approaches for multiple levels may require a collection of theories addressing behavior and behavior change at each component level, whereas others have recommended a consolidated framework across often overlapping theories to help explain implementation in multilevel contexts (33). Related fields offer additional guidance in identifying theories for use in multilevel implementation [eg, patient (31,34), professional (35), and organizational behavior change (15)] and are addressed in other chapters (36,37). Theories in political science and policy studies also are available to help researchers address levels of government and regulatory agencies (30,32). In addition to theories offering detailed depictions of causal relationships, a number of planning frameworks (eg, Predisposing, Reinforcing and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation [PRECEDE]-Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development [PROCEED]) and conceptual models (eg, Chronic Care Model) identify broad categories of factors to consider, although many stop short of specifying individual causal relationships and influences of these factors (38,39).

Cancer and Noncancer Examples for Examining Implementation and Spread

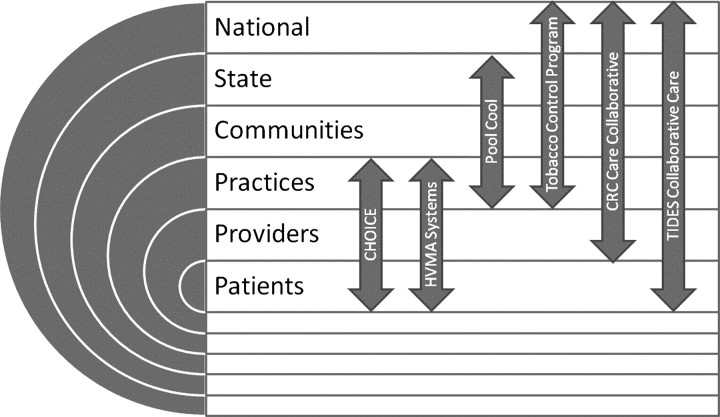

To grapple with these issues, we drew on our combined experience with a series of interventions whose implementation and spread spanned different levels (Figure 1 and Table 2). Because the use of multilevel interventions in cancer care is still developing, we also included a noncancer example that has spanned virtually all levels. Use of theory is well reflected in the examples chosen.

Figure 1.

Implementation and spread of interventions into multilevel contexts of routine practice and policy, levels covered by cancer and noncancer examples. CHOICE = Communicating Health Options through Information and Cancer Education (40,41); HVMA Systems = Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (42,43); Pool Cool Diffusion Trial, skin cancer prevention program (44); Tobacco Control Program (34,45); CRC Care Collaborative = Veterans’ Health Administration Colorectal Cancer Care Collaborative (C4) (5); TIDES Collaborative Care = Translating Interventions for Depression into Effective Care Solutions, depression collaborative care (46–48).

Table 2.

Description of examples for implementing and spreading interventions into multilevel contexts*

| Example | Intervention levels | Setting(s) | Design | Data collection | Measures |

| Pool Cool Diffusion Trial (skin cancer prevention program) (39,49) | Field coordinators Swimming pools (recreation centers) Children (ages 5–10 y) |

32 metropolitan regions across United States, each responsible for cluster of 4–15 pools per coordinator | Three-level nested experimental design with field coordinators randomized to Basic and Enhanced (reinforcement plus feedback) diffusion conditions over 3 years Process evaluations among key stakeholders at multiple levels |

Pool managers surveyed each summer Sample of parents at each pool surveyed about their children (baseline and end of each summer) Cohort subsample followed over multiple years Interviews and formative progress reports |

Pool-level implementation, maintenance and sustainability over successive years Organizational/environmental change at pools Child sun-protection habits and sunburns |

| CHOICE (40,50) | Practice-level (physician practices with Aetna HMO and ≥50 members ages 52–75 y) Patient-level (health-plan members) |

32 primary care practices in FL† and GA† and 443 participating health plan members (211 in intervention practices, 232 in usual care practices) | Cluster randomized controlled trial Modified blocked randomization, stratified on practice size, number of eligible members and urban/rural Augmented enrolled patients (eligible per completed baseline survey) with nonresponders (for whom claims data were reviewed) |

Practice surveys (before and at end of study) Patient surveys (eligibility, baseline and follow-up surveys at 12 and 18 mo) (multimodal, ie, mail, telephone, web) Claims data (CRC screening in addition to patient surveys) |

Physician practices’ CRC screening practices, referrals and quality improvement initiatives Patient CRC screening test completion Patient interest in CRC screening, intent to ask providers about screening, readiness to be screened |

| Improving Systems for Colorectal Cancer Screening (51,52) | Integrated medical group (HVMA) Primary care physicians Adults (ages 50–80 y) who were overdue for screening |

Multispecialty, integrated medical group serving approximately 300 000 patients at 14 clinical centers in Eastern MA† | 2 × 2 design Approximately 22 000 patients randomized to receive mailed reminders and FOBT cards 110 primary care physicians randomized to receive patient-specific electronic clinical reminders during office visits for patients who were overdue for CRC screening Subsequent randomized study of electronic reminders and web-based CRC risk index from primary care physicians to approximately 1100 patients who were overdue for CRC screening and were registered users of web-based patient portal in EMR |

EMR data Physicians surveyed after the intervention |

Patient completion of FOBT testing, flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy over 15 mo Detection of CRC or adenomas among adult patients Physician views of CRC screening and value of electronic reminders |

| Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs (45,53) | National policy (government and advocacy groups) State policy State tobacco control programs Local initiatives Community-based settings |

State and local departments of health and education Schools Worksites Restaurants Bars |

Multiple studies with different designs at different levels (eg, time series and multiple baseline studies) Individual state-level evaluations National evaluation Federally-funded intervention studies (eg, COMMIT, ASSIST, IMPACT, NTCP) Cost–benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses (eg, if children protected from secondhand smoke, could prevent more than a million asthma attacks and lung and ear infections) |

Local, state, and national surveillance (eg, BRFSS, national and state Adult Tobacco Surveys, Youth Tobacco Surveys, Current Population Survey Tobacco Use Supplement) Individual intervention studies on tobacco use screening, brief interventions by clinicians, quitlines, tobacco use treatment and coverage, etc. Media studies tracking appearance of tobacco news and other items in popular press, counter-advertising coverage |

Tobacco consumption or cessation ratesCigarette sales Heart disease deaths Lung cancer incidence Hospitalization ratesTobacco control program spending Coverage of tobacco issues/developments in popular media (content analyses of news stories) Use of quitlines and other cessation services Policy changes Changes in social norms Legislative tracking |

| TIDES (46–48) | Primary care practices and their providers Associated local medical care system leadership and mental health specialists Regional system interdisciplinary leadership National research–based QI organization (QUERI) National system patient care services policy makers |

VA medical centers and community-based outpatient clinics Early pilot in 1 VA practice Trial in 10 practices Spread to >60 practices National implementation |

Multiple studies with different designs, all with purpose of providing formative information to lead to effective national policy All based on collaborative care model tested in multiple randomized trials and validated in meta-analysis Cluster randomized trialQualitative data and analysis at the levels of the care model evidence-based QI intervention,and the national policy intervention Prepost testing of individual patients participating in the collaborative care intervention |

Consecutive primary care patients screened for depression and tested for process of care and clinical outcomes Local primary care practices, including nurses, primary care clinicians, and mental health specialists directly observed and interviewed Regional and national policy activities tracked Primary care providers surveyed Costs of the intervention and implementation tracked |

Qualitative themes Rates of initiation of antidepressants Depression symptoms Functional status Utilization (primary care and mental health visits, hospitalizations) Provider knowledge, attitudes, behaviors (including comfort with managing depression, degree of collaboration) Practice-level measures of structures, processes and implementation |

| VHA Colorectal Cancer Care Collaborative (C4) Cancer Care Quality Measurement System (43,54) | National policy National quality and performance managers Regional leadership (VA networks) Medical centers (leadership and quality managers) Community-based outpatient clinics Primary care practices and their providers |

VA medical centers and community-based outpatient clinics Initial studies single site chart review and national data analyses Collaborative comprises 21 medical centers (one from each VA network) Best practices disseminated to all medical centers |

Quarterly audit and feedback of chart-based performance measures Comparative facility-level analyses within and across VA networks |

Externally conducted chart reviews of CRC screening among random samples of eligible veterans Electronic data abstraction tool into which teams enter patient-specific data for CRC treatment measures (about 230 data elements used to evaluate compliance with 24 quality indicators) |

CRC screening: CRC screening for all average or high-risk patients60-d follow-up diagnostic tests of positive screens CRC treatment: Treatment indicators (eg, proportion of patients with T3 or T4 lesions and/or node+ disease referred to medical oncologists); timeliness of treatment processes (eg, dosing/timing of chemotherapy, adjuvant radiation); postsurgical surveillance |

*ASSIST = American Stop Smoking Intervention Study for Cancer Prevention; BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CHOICE = Communicating Health Options through Information and Cancer Education; COMMIT = Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation; CRC = colorectal cancer; EMR = electronic medical record; FOBT = fecal occult blood test; HMO = health maintenance organization; HVMA = Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates; IMPACT = Initiatives to Mobilize for the Prevention and Control of Tobacco Use Program; NTCP = National Tobacco Control Program; QI = quality improvement; QUERI = Quality Enhancement Research Initiative; TIDES = Translating Initiatives in Depression into Effective Care Solutions; VA = US Department of Veterans Affairs health-care system; VHA = Veterans’ Health Administration.

†32 primary care practices included in CHOICE study are in Florida (FL) and Georgia (GA). 14 clinical centers included in Improving Systems for Colorectal Cancer Screening study are in Massachusetts (MA).

Pool Cool Diffusion Trial

The Pool Cool Diffusion Trial tested a three-level skin cancer prevention program at recreational swimming pools (44). To implement, disseminate, and evaluate the program, the project team had to build effective relationships with professional organizations and recreation sites at national, regional, and local levels. This was achieved by participating in aquatics and recreation conferences, developing career opportunities and encouraging local media coverage of program activities (55,56), and providing resources to conduct the program after research participation concluded (57).

The Pool Cool program drew from social cognitive theory (58), diffusion of innovations theory (59–61), and theories of organizational change (49). These models are complementary, with considerable overlap among them (50,58). The investigators’ intent was not to test a single model but to apply the most promising constructs from each to the problem of skin cancer prevention and program diffusion in aquatics settings.

Improving Systems for Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Screening and Follow-up in Clinical Practices

Three examples focused on CRC screening, one of which also focused on follow-up.

CHOICE (Communicating Health Options Through Information and Cancer Education).

CHOICE combined patient activation through decision aides and brochures among health plan members with academic detailing to prepare practices to facilitate CRC screening for activated patients (40,41). A cluster randomized trial, CHOICE required extensive engagement and partnership development at all levels. The CHOICE intervention relied on social cognitive theory (multiple levels) and the transtheoretical model of change (stages of change) (for the decision side, patient/member level) (51,62).

Improving Systems for CRC Screening at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (HVMA).

Sequist et al. designed randomized multilevel systems interventions to assess whether CRC screening could be increased among overdue adults. The study was conducted at HVMA, a large integrated medical group in Eastern Massachusetts. Screening rates were higher for patients who received mailings compared with those who did not, and the effect increased with patients’ age (42). Screening rates were similar among patients whose physicians received electronic reminders and those whose physicians were in the control group. However, reminders tended to increase screening rates among patients with three or more primary care visits over the 15-monthintervention. Adenoma detection tended to increase with both patient mailings and physician reminders. With a cost-effectiveness ratio of USD $94 for each additional patient screened, patient mailings were deemed cost-effective for continued use by the organization (43).

Improving CRC Screening and Follow-up in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

Improving CRC screening has been a longstanding national priority in the VHA health-care system, followed by more recent emphasis on managing timely, complete endoscopic follow-up and treatment. These examples span the VHA Colorectal Cancer Care Collaborative (C4) and Veterans Affairs (VA) Colorectal Cancer Quality Monitoring System (54,63), which grew out of QUERI (Quality Enhancement Research Initiative) (64,65).

The HVMA and VHA examples were more explicitly anchored in principles of continuous quality improvement during implementation phases, guided by Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles. Originally proposed by Langley et al. (66), amplified by Berwick (67), and applied in QUERI (64,65), PDSAs have often been used for smaller-scale rapid-cycle improvements. PDSA has also been adopted for broader organizational initiatives to improve quality of care (68). Stone et al. (53) have augmented this approach to guide quality improvement interventions to promote cancer screening services, identifying several key intervention features, including top management support, high visual appeal and clarity, collaboration and teamwork, and theory-based tailoring of interventions based on current needs and barriers. In both HVMA and VHA examples, these insights were primarily used during planning and pilot phases, when study interventions at different levels were refined with input from organizational leaders and pilot testing at one or more health centers or practices.

Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs

The Office on Smoking and Health of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) examined the experience of several successful statewide tobacco control programs in the early to mid-1990s (particularly California and Massachusetts, but also specific lessons drawn from Arizona, Oregon, Florida, and Mississippi in the mid- to late-1990s). They blended these programs with the evidence-based literature on tobacco control from other sources to produce a widely adopted document titled Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs (45). A second edition was published in 2007, based on the growing evidence from other states after following the lead of the initial states and another CDC document, Introduction to Program Evaluation for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs (69). On reviewing the evidence of effective comprehensive statewide programs, CDC concluded that no single intervention by itself, other than sharply increased prices on cigarettes through taxation, could account for the significant changes in tobacco consumption found over time. California and Massachusetts, in particular, doubled, tripled, and then quadrupled the rate of decline in tobacco consumption of the other 48 states while implementing their comprehensive statewide programs. Less comprehensive programs had successes in specific subpopulations, on specific outcomes, at specific levels of their states, but not as dramatic as California's or Massachusetts's comprehensive, multilevel programs. This example spans national and state policy changes as an overlay to organizational-level interventions that occurred, for example, in schools, worksites, and restaurants within statewide programs. The overriding theoretical framework for the tobacco control programs was social normative theory, which drove the mass media and smoke-free policy initiatives and which, in turn, undermined the tobacco industry's promotions and the acceptance of smoking in public (70–72).

TIDES (Translating Initiatives in Depression Into Effective Solutions)

The TIDES initiative, which began with a planning phase in 2001 and enrolled its first patients in 2002, used evidence-based quality improvement (EBQI) methods as the basis for redesigning, adapting, and spreading collaborative care models for improving outcomes among primary care patients with depression. Collaborative care models have been shown to be effective and cost-effective based on more than 35 randomized trials and meta-analyses. Also supported by the VA QUERI program, TIDES was a multiregion EBQI effort to adapt and implement the research-based depression collaborative care models to the context of the large national VA health-care system.

The EBQI approach used regional and local iterative meetings to adapt and tailor collaborative care evidence—a multicomponent intervention directed at primary care patients who screen positive for depression—to the VA context. Key intervention features included a depression care manager supervised by a mental health specialist, structured assessment and follow-up of depressed patients, and patient self-management support. Key EBQI features are regional leadership priority setting, a research/clinical partnership with involvement of technical experts, and iterative intervention development with provider- and practice-level feedback on collaborative care intervention performance. The overriding goal of the series of projects that comprised the TIDES initiative was to use regional and local adaptation of the evidence-based care model as the basis for national VHA implementation, which occurred in 2006. The VHA-only SharePoint website, which houses TIDES tools and methods, continues to be accessed about 2000 times per month from all VHA regions across the country, in addition to an internet site sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (http://www.ibhp.org). In addition to continuous quality improvement, TIDES also relied on the Chronic Illness Care model (39) and tenets of social marketing (73).

Lessons Learned About Implementation and Spread of Interventions Into Multilevel Practice and Policy

Table 3 provides a summary of the lessons learned about the implementation and spread of interventions into multilevel practice and policy. Several key themes emerged from our examination of these diverse examples.

Table 3.

Lessons learned from examples regarding implementation and spread of interventions into multilevel contexts*

| Example | Intervention combinations (strategies for combining interventions at different levels to produce complementary or synergistic effects) (36) | Time and timing (growth trajectories, early vs late effects, intervening effects, time-varying predictors) (74) | Partnerships required within and across levels (types, engagement, contributions/support, communication) (75) | Implementation facilitators/barriers (within and across levels, contextual implications) (75) | Issues of spread and sustainability (determinants, handoffs, long-term evaluation, and monitoring) |

| Pool Cool Diffusion Trial (skin cancer prevention program) (39,49) | Organization and environmental change at the pool level Education and behavioral strategies at the individual level |

Three phases, including implementation, maintenance Enhanced strategies took hold over time |

Regional partnerships required to maintain organizational level changes Community support key to sustainability |

Variable enthusiasm and champions for prevention (eg, stability, attention to follow-through) Higher degree of control over pools in region resulted in greater consistency of implementation Interplay between demand for and adoption of intervention could not be fully predicted in advance Weather variation was a contextual barrier at times |

Funding priorities and champion were needed Three-year duration of project, then handed off to local “ownership” Continual measurement of local implementation key |

| CHOICE (40,50) | Decision aide and stage-targeted brochures at patient level (activation) Academic detailing to prepare practices to facilitate CRC testing at practice level after patient activation |

Early detailing provided knowledge, audit and feedback of current CRC screening rates, facilitated discussion of current practice strategies and planned changes Later detailing after most patient interventions mailed, with plan reviews, iterative problem-solving |

Partnership between two university research teams and regional health plan quality management department Partnerships between detailers and practice physicians Level of practice and physician engagement key Practice/physician accountability/uptake between detailing contacts important Successful practice response requires other providers outside of primary care (no intervention component for others included) |

Initial practice recruitment low (need to identify barriers) Physician attendance at detailing sessions incomplete at initial session and low for subsequent sessions Incomplete exposure to decision aids (some did not watch video and/or did not read brochures) Practices treated patients from other health plans not part of intervention Practice busy with competing demands precluding focus on a given cancer prevention activity More intensive interventions at both practice and patient levels may be necessary |

Researchers sent decision aids to patients, lacking personal authority and participation of practice in sustainable action (no explicit handoffs) In IPA-model HMOs, medical practices relate to multiple health insurers, which may be a barrier to spread Patient-level intervention tools need to be adapted for different populations (eg, with and without socioeconomic barriers) |

| Improving Systems for Colorectal Cancer Screening (51,52) | Patients and their physicians receiving reminders in parallel Multilevel quality improvement programs needed to reconcile screening preferences of patients and physicians |

Substantial organizational experience using EMR to identify patients eligible for interventions and to track processes and outcomes of care | Strong support from senior clinical leaders in medical group Study introduced to primary care physicians in staff meetings at each participating health center Close involvement of senior quality improvement manager at group with research team overseeing aspects of developing, implementing and evaluating intervention (eg, data capture, tracking patients) Experienced IT staff to implement electronic reminders and data warehouse |

Feasibility and implementation facilitated by well-established EMR, medical group experience with centralized outreach to patients for QI, new endoscopy center opened to expand screening colonoscopy capacity Some health plans incorporated pay-for-performance for CRC screening in contracts with local medical groups Guided by PDSA for rapid cycle improvements during planning and pilot phases |

Introduction of new HEDIS measure for CRC screening State policy context with four major health insurers, top-rated US health plans, motivated to achieve high CRC screening rates Statewide quality monitoring program released public reports on CRC screening for medical groups in state |

| Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs (45,53) | National best practices toolkit (blended scientific literature and experience from successful state programs) National funding, social marketing, and technical assistance State legislation on tobacco control, retail compliance, etc. State tobacco control initiatives (funding, coalition development, media campaigns, surveillance, training/support) Local initiatives (adapted to local settings, issues, and populations) Array of patient, provider and community interventions |

From statewide tobacco control programs (esp. CA, MA, also NY, WA, AZ, AK, OR, FL, MS, MN, IN, CO, DE)† to national dissemination Strength of early state-level impacts (two- to fourfold decline in tobacco consumption in CA and MA) influenced national adoption CDC best practices reports concurrent with Master Settlement funds becoming available from lawsuit against tobacco industry (funds for tobacco control programs) |

National agencies examined/funded evidence base (eg, systematic reviews, policy groups, dissemination of successful programs) Federal funding to states through block grants States provided needed support to local programs (covered activities localities could not afford such as media campaigns) Local programs required to complement statewide efforts of departments of health and education Coalition-building at national, state, and local levels and coordination between levels to engage array of stakeholders |

More components and levels actively mobilized the more effective statewide tobacco control outcomes Value of evaluation data at individual intervention levels and multilevel aggregated findings More spent on tobacco control, the greater the smoking reductions Longer the investment in tobacco control, the greater and faster the impacts Growing public recognition of tobacco industry tactics and changing social norms toward smoking in public accelerated acceptance of smoke-free laws and their enforcement |

Long-term surveillance of tobacco use and related outcomes essential for making business case Early national agreement on criteria and measures of success for surveys and other evaluation tools CDC best practices report as touchstone for comprehensive program planning (immediately applicable and timely with per capita recommendations for budget allocations) |

| TIDES (46–48) | Use of social marketing to tailor messages to diverse groups Use of expert panel methods to ensure regional support for local intervention design and implementation Use of iterative intervention development based on the evidence and continuous quality improvement principles to tailor the intervention |

Bottom–up intervention design guided by regional priorities Early local and regional development linked to national policy influence and design |

Studies focused on engaging regional leadership and, through regional leadership, regional experts and local sites in iterative development and testing of the intervention Studies also focused on understanding and linking in management and policy at regional and national levels |

Established funding mechanisms for research were inadequate Informatics-based communication and decision support promoted ease of operation/adoption Integrated interdisciplinary nature of intervention (primary care, mental health specialist, nursing) encountered barriers/resistance at all levels Presence of local clinical champion accelerated implementation Academic detailing and other education/training critical Regional leadership (administrative, primary care, mental health, nursing) strongly facilitated intervention development |

No clear established path for handing off an intervention that spanned clinical disciplines and multiple leadership-levels Difficult to establish program-oriented (vs eg, standard performance measure) ongoing evaluation of program quality at local and regional levels |

| VHA Colorectal Cancer Care Collaborative (C4) (43,54) | Built on foundation of evidence from QUERI Organized efforts around QI collaboratives: 1) screening and diagnosis, 2) treatment and surveillance Continual integration of new research evidence (problem identification and interventions) Interventions adapted to local needs, situations (eg, menu of options) |

Early and iterative use of PDSA rapid cycles of improvement Started with focus on screening and diagnosis, followed by treatment QI Started with one pilot site in each network to other sites in remainder of network Built QI infrastructure and then implemented process change strategies |

National VA policy and practice leaders partnered with health services researchers and experts from VA System Redesign National oversight and incentives linked to individual networks and medical centers Local and regional partnerships between clinicians and informatics experts (design optimal tools for computerized decision support) |

EMR tools (eg, clinical reminders, alerts) (national mandates and local adaptations) Groups of teams met and/or had calls regularly to set aims, do “pre-work” (eg, flow mapping care), get educated, share ideas, successes, and problem solve Regular reporting to national project organizers and to participating medical centers’ leadership kept momentum going Best evidence summarized and disseminated in improvement guide Continual audit and feedback of results at multiple levels |

Leadership support of and protected time for QI teams Support network for QI teams (share, adopt, adapt ideas across sites) Regional collaboratives where original pilot sites assist other facilities in their area Introduction of quality monitor requiring all facilities to track compliance Dissemination of centrally developed tracking tool EMR notes, reminder templates QI listservs and resource websites |

*CHOICE = Communicating Health Options through Information and Cancer Education; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CRC = colorectal cancer; EMR = electronic medical record; HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness and Data Information Set; HMO = health maintenance organization; IPA = independence practice association; IT = information technology; PDSA = Plan-Do-Study-Act; QI = quality improvement; QUERI = Quality Enhancement Research Initiative; TIDES = Translating Initiatives in Depression into Effective Care Solutions; VA = US Department of Veterans Affairs health-care system; VHA = Veterans Health Administration.

†State tobacco programs included in Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs are as follows: Arizona (AZ), Arkansas (AR), California (CA), Colorado (CO), Delaware (DE), Florida (FL), Indiana (IN), Massachusetts (MA), Minnesota (MN), Mississippi (MS), New York (NY), and Oregon (OR).

Combinations and Phases of Multilevel Intervention Implementation

Attention to the nature of stakeholders at each level is key to successful implementation of a multilevel intervention, as is a strong understanding of how levels may interact. For example, in CHOICE, academic detailing was designed to prepare providers for patients activated by the decision aide. The HVMA delivered patient and provider reminders in parallel. Creating interdependencies also can be beneficial, for example, when local programs received tobacco control funding for mapping to state-level program activities or where local facilities received incentives for achieving compliance with CRC follow-up performance monitors. Determining the quality of the evidence (and continually integrated new evidence) for the interventions being deployed at each level also is important. However, when the evidence is lacking, blending scientific literature with experience from successful programs can be especially useful. Use of social marketing strategies also provided interventional messaging that penetrated multiple levels, though messages often have to be honed for each level's target audience (ie, what rivets the attention of patients likely differs from that of providers or policymakers). Several projects emphasized rapid cycle improvement pilots to test functions and effectiveness of implementation efforts within and across levels. This approach is especially important given the size and complexity of multilevel interventions and the importance of balancing fidelity and flexibility when adapting to local contexts.

Implementation also benefited from staged approaches, beginning with pilot testing within levels at a single practice or community followed by broader implementation as details and needs at each level become clearer (5). Recognition of the time needed for changes to penetrate each level's members’ knowledge and behavior is often underappreciated. For example, many multilevel interventions rely on champions, which requires education/training of the champion and then their peers or constituents (either by the champion or project team) through formal or informal social networks (76).

The direction of implementation—top–down vs bottom–up—also is an important distinction. In the Pool Cool program, the demand for and interest in the program went in different directions at different levels of the intervention. In some regions, motivated leaders at the top sometimes dictated program involvement, whereas in other regions, someone from a “lower level” (eg, a specific pool) was resourceful enough to find other sites and resources to bring the program to the local area. Tobacco control successes clearly moved from local and state levels to the national level for dissemination to other states that could emulate successful states’ practice-based experience, blended with evidence-based practices from controlled trials on specific interventions. TIDES also grew from a bottom–up intervention design guided by regional priorities and later was adopted nationally. Experiences from these programs, as well as others, also point to the importance of comprehensive process evaluations to measure the levers and directions of implementation, as well as the processes used, if any, to promote activity and align interests at different levels.

Partnerships Within and Across Levels

The importance of partnerships within and across levels and between researchers, clinicians, and managers was a clear and consistent theme across the examples, reflecting in large part the reduced control that researchers have over implementation dynamics on each level and the need to hand off intervention activities to nonresearchers—otherwise, it would not be “routine care” (5). To fit local conditions, proactive and intentional adaptations to the environmental and organizational milieu represented by each partnership level (eg, practice tailoring) reduce the risk of failed implementation (77–84). Such partnerships require shared knowledge, trust, and role specification; require time spent in relationship- and team-building before, during and after implementation (with changing roles over time); and continual identification of a growing network of stakeholders who will ultimately maintain and be responsible for the intervention components at their level. Few studies have documented the costs associated with such implementation, with the exception of TIDES, which demonstrated substantial contributed time by implementers and researchers (85).

Strong support from senior leaders is also essential. Policy, community, practice, and other leaders help ensure engagement of members at their respective levels and frequently secure and allocate resources while also encouraging other participants who may need to be involved (eg, engaging gastroenterology and/or radiology specialists in primary care–based efforts to improve CRC screening). Senior leaders also are accountable for implementation and maintenance activities between research team contacts and may play a major role in coalition building. Partnerships with health information technology staff also were considered key, especially in settings with electronic medical records (EMRs).

Implementation Barriers and Facilitators

Consistent with the Institute of Medicine's Crossing the Quality Chasm report (86), our examples point to the importance of organizational supports for implementation. In some scenarios, such supports may be centralized across a large number of sites (eg, computerized decision support in practices with a shared EMR or state-level media campaigns for tobacco control) and may include direct grants, special funding allocations, and/or protected time for quality improvement and training. The degree of leadership control over a particular level may also increase the consistency of implementation, especially when supported by regular feedback of evaluation data. For example, in the HVMA CRC screening intervention, organizational leaders fully endorsed the programs being developed, allowing key quality improvement staff to participate actively in their design and implementation. However, implementation that requires interdisciplinary cooperation may be met with resistance when members at a particular level compete for resources or control or operate in silos where communication and coordination mechanisms may not have been developed. The perceived importance or value of implementation goals must be balanced with competing demands among busy members at any given level (87,88). These kinds of implementation barriers may not be predictable, underscoring the value of planning phases, “pre-work,” and PDSA cycles as integral components of implementation efforts.

Understanding Policy Context, Fiscal Climate, and Performance Incentives

Insofar as all behavior is affected by context, our examples demonstrated the vital importance of understanding the contextual influences surrounding players at each level of implementation. For example, the policy context in Massachusetts during the time of the HVMA CRC screening initiative was a virtual “perfect storm” in favor of implementation, as confirmed in structured interviews with HVMA chief medical officers, another large integrated provider network in the same region, and two regional insurers. The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) had introduced a new Healthcare Effectiveness and Data Information Set (HEDIS) measure for CRC screening in 2004 (89), with two of Massachusetts's four major insurers having participated in NCQA's field testing of the new measure. Pay-for-performance incentives for CRC screening rates also were being incorporated in some health-plans’ provider contracts, and a statewide quality monitoring program, Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (http://www.mhqp.org), was preparing to release statewide public reports on medical groups’ CRC screening rates. In other states without this policy context, the same level of adoption and participation might not have been seen.

Similarly, the rapid adoption and implementation of practice-based evidence for tobacco control from California and Massachusetts was accelerated by the Master Settlement Agreement between the states’ attorneys-general and the tobacco industry, which infused large amounts of earmarked funds into state tobacco control budgets. Implementation in settings where the fiscal climate is more difficult requires advance assessment of practice priorities and placement of the intervention among competing demands, in addition to adapting to local constraints.

Determinants of Spread

Few examples of intervention spread are generally available. Among our examples, the spread of successful tobacco control programs benefited from CDC's best practices document as a touchstone for planning programs at a time when the Master Settlement funds became available from the lawsuit filed against the tobacco industry, making its publication both timely and immediately applicable. Although such timing may occur serendipitously, implementation clearly benefits when advances at different levels of influence co-occur.

In the 4 years since the HVMA CRC screening interventions were originally implemented, the CRC screening rates have continued to rise from 63% to about 85%, which is one of the highest publicly reported rates for any medical group, health-plan, or region in the United States. This high rate was achieved through a strong organizational commitment to CRC screening, an advanced EMR for tracking CRC screening and other preventive services, and an expanded capacity to perform screening colonoscopy (by about 300 procedures per month) at a new HVMA endoscopy center.

Champions can support spread in addition to implementation, for example, through initial practices’ sharing of their experiences and troubleshooting with spread practices. Such person-to-person support, however, may best be accomplished when augmented with tools that facilitate adoption in new locations (eg, tracking tools, compendia of evidence, listservs, resource websites), adaptation to new populations (or subgroups), and measurement and evaluation.

However, one of the keys to implementation and spread based on these examples is the explication of the handoffs of multilevel intervention activities from researchers to accountable individuals within and across levels. When researchers support implementation by offloading certain activities from providers, they are unintentionally creating a nonsustainable situation. Furthermore, when multilevel interventions engage several clinical disciplines and multiple levels of leadership, no single handoff strategy is likely to succeed. Better assessments of usual practice, development of explicit memoranda of understanding (ie, spelling out the details of new roles and responsibilities), and continual management of research–clinical partnerships help alleviate at least some of these issues.

Sustainability: End Game or Myth?

Implementation of current evidence remains painfully slow, and the evidence base itself may not change as fast or as dramatically as often implied. Nonetheless, one of the reasons it is difficult to implement and spread evidence-based practice is that the levels of implementation are often changing. Practices face provider and staff turnover and leadership changes, and the political environment is always evolving. Just as multilevel influences are in perpetual motion, so is the evidence base to support interventions. New trials are completed, whereas observational studies contribute new information to our understanding of the factors involved in patient, provider, or organizational behavior and beyond. It is therefore important to continually scan and integrate new evidence over time: Sustainability may be a myth as there is always new evidence to consider, new people to train, practices opening and closing, communities adapting to new contexts, and state and federal agencies and their priorities changing. Unfortunately, systematic reviews, in their typically exclusive reliance on randomized controlled trials, will not close the information gap in the strategies for implementation, spread, and sustainability.

Based on the examples we reviewed, the best evidence for sustainability is long-term and continual attention to influences within and across all levels, enabled by engagement of people and places with ever increasing and overlapping spheres of influence (90). Integration of evidence into new national norms, regardless of how such norms are fostered or reinforced (eg, through performance measures, new reimbursement policies or legislation), is an essential method for sustaining multilevel change, though the path at the national level is complex and circuitous at best.

Methodological Challenges

While full treatment of the range of study design and other methodological issues rooted in implementation and spread research are beyond the scope of this monograph, Table 2 provides insights into the methodological approaches each example used, as well as the challenges they faced. Key issues span study design complexity, geographic scope, measures and data collection mapped to multiple levels and over multiple waves, and the inherent value of EMR systems for supporting evaluation and monitoring.

Conclusions

In this chapter, we used several exemplary studies to illustrate key concepts underlying the implementation and spread of interventions into the multilevel contexts of routine practice and policy. Lessons from these studies provide insights into approaches for handling implementation of interventions and partnerships within and across levels, as well as facilitators and barriers for their implementation, spread, and sustainability.

Advancing implementation will continue to be a challenge for the foreseeable future. Discomfort with the compromises inherent in the naturalistic rollout of intervention activities at multiple levels (in contrast to experimental control focused on reducible variation) slows our ability to meet these challenges. Criticisms against multilevel intervention research are also misguided when they are based on the contention that it is inherently difficult to discern the relative contributions of each intervention component. Experience from our examples suggests that they produce synergies and complementary effects, which require mixed methods and may benefit from hybrid designs to yield useful information. Furthermore, implementation requires expertise in politics and diplomacy, skills rarely taught in scientific curricula, in addition to flexibility, comfort with uncertainty, and persistence.

Experiences from our examples offer a potential roadmap for improving the design and evaluation of multilevel interventions focused on the cancer care continuum. The methodological challenges will require ongoing investment in interdisciplinary mixed methods of research and evaluation, and greater emphasis on the training/education of a growing cadre of investigators and research teams skilled at building and bridging diverse partnerships, without which most implementation will not be systematically studied. Such an investment should pay dividends by increasing the number of levels effectively combined and examined, the quality of the evidence deployed at each level, and, ultimately the impact on routine practice and population health outcomes.

Funding

This work was coordinated by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. EMY's time was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) through the Veterans Health Administration Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Service through a Research Career Scientist award (05-195). JZA was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA112367).

Notes

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the planning group in the Behavioral Research Program at the National Cancer Institute for their review of and input on multiple revisions of this monograph chapter. The authors are also grateful to Thomas D. Sequist and Eric C. Schneider for interviewing clinical leaders regarding the HVMA CRC screening interventions. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Bradley EH, Webster TR, Baker D, et al. Translating research into practice: speeding the adoption of innovative health care programs. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2004;724:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinbrook R. The potential of human papillomavirus vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1109–1112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markman M. Cancer screening: understanding barriers to optimal use of evidence-based strategies. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(1):9–10. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKenna H, Ashton S, Keeney S. Barriers to evidence based practice in primary care: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41(4):369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubenstein LV, Pugh J. Strategies for promoting organizational and practice change by advancing implementation research. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21((suppl 2)):S58–S64. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Driel ML, De Sutter AI, Christiaens TCM, DeMaeseneer JM. Quality of care: the need for medical, contextual and policy evidence in primary care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11(5):417–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oxman T, Dietrich A, Schulberg H. The depression care manager and mental health specialist as collaborators within primary care. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11(5):507–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solberg LI. Improving medical practice: a conceptual framework. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(3):251–256. doi: 10.1370/afm.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sammer CE, Lykens K, Singh KP. Physician characteristics and the reported effect of evidence-based practice guidelines. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(2):569–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00788.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zapka JG, Taplin SH, Solberg LI, Manos MM. A framework for improving the quality of cancer care: the case of breast and cervical cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(1):4–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiore MC. U.S. Public Health Service clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence. Respir Care. 2000;45:1200–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richard L, Potvin L, Kishchuck N, Prlic H, Green LW. Assessment of the integration of the ecological approach in health promotion programs. Am J Health Prom. 1996;10(4):318–328. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Commers M, Smerecnik C. The ecological approach in health promotion programs: a decade later. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22(6):437–442. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Glasgow RE. Review of external validity reporting in childhood obesity prevention research. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yano EM. Influence of health care organizational factors on implementation research: QUERI Series. Implement Sci. 2008;3(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley F, Wiles R, Kinmonth AL, Mant D, Gantley M for the SHIP Collaborative Group. Development and evaluation of complex interventions in health services research: case study of the Southampton Heart integrated care project (SHIP) BMJ. 1999;318(7185):711–715. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7185.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krein SL, Damschroder LJ, Kowalski CP, Forman J, Hofer TP, Saint S. The influence of organizational context on quality improvement and patient safety efforts in infection prevention: a multi-center qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(9):1692–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litaker D, Tomolo A. Association of contextual factors and breast cancer screening: finding new targets to promote early detection. J Womens Health. 2007;16(1):36–45. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bamberger P. Beyond contextualization: using context theories to narrow the micro-macro gap in management research. Acad Manage J. 2008;51(5):839–846. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;(44):2–10. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zapka J, Taplin SH, Ganz P, Grunfeld E, Sterba K. Multilevel factors affecting quality: examples from the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;(44):11–19. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green LW, Glasgow R. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: issues in external validation and translation methodology. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(1):126–153. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green LW, Glasgow RE, Atkins D, Stange K. Making evidence from research more relevant, useful, and actionable in policy, program planning, and practice: slips “twixt cup and lip”. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6S1):S187–S191. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodenheimer T California Healthcare Foundation. The science of spread: how innovations in care become the norm. Published September 2007. Accessed March 15, 2012 California Healthcare Foundation Web site. http://www.chcf.org/publications/2007/09/the-science-of-spread-how-innovations-in-care-become-the-norm. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilbourne AM, Schulberg HC, Post EP, Rollman BL, Belnap BH, Pincus HA. Translating evidence-based depression management services to community-based primary care practices. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):631–659. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawe P, Shielle A, Riley T, Gold L. Methods for exploring implementation variation and local context within a cluster randomized community intervention trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(9):788–793. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.014415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green LW. Making research relevant: if it's an evidence-based practice, where's the practice-based evidence? Fam Pract. 2008;25(suppl 1):20–24. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn055. [published online ahead of print September 15, 2008] doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhattacharyya O, Reeves S, Garfinkel S, Zwarenstein M. Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions: fine in theory, but evidence of effectiveness in practice is needed. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slotnick HB, Shershneva MB. Use of theory to interpret elements of change. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002;22(4):197–204. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340220403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ottoson JM, Green LW. Reconciling concept and context: a theory of implementation. Adv Health Educ Prom. 1987;2:353–382. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green LW, Ottoson JM, Garcia C, Hiatt R. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization and integration. Ann Rev Public Health. 2009;30(1):151–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ottoson JM. Knowledge-for-action theories in evaluation: knowledge utilization, diffusion, implementation, transfer, and translation. New Directions for Evaluation. 2009. pp. 7–20. 2009(124, special issue)

- 33.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implem Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—2007. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A on behalf of the “Psychological Theory” Group. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence-based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiner BJ, Lewis MA, Clauser SB, Stitzenberg KB. In search of synergy: strategies for combining interventions at multiple levels. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;44:34–41. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stange KC, Breslau ES, Dietrich AJ, Glasgow RE. State-of-the-art and future directions in multilevel interventions across the cancer control continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;44:20–31. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health Program Planning. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, Davis C, et al. Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach. Jt Comm J Qual Improve. 2001;27(2):63–80. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis C, Pignone M, Schild LA, et al. Effectiveness of a patient and practice-level colorectal cancer screening intervention in health plan members: design and baseline findings of the CHOICE Trial. Cancer. 2010;116(7):1164–1173. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pignone M, Winquist A, Schild LA, et al. Effectiveness of a patient and practice-level colorectal cancer screening intervention in health plan members: the CHOICE Trial [published online ahead of print February 11, 2011] Cancer. 2011;117(15):3352–3362. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25924. doi: 10-1002/cncr.25924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sequist TD, Zaslavsky AM, Marshall R, Fletcher RH, Ayanian JZ. Patient and physician reminders to promote colorectal cancer screening: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(4):364–371. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sequist TD, Franz C, Ayanian JZ. Cost-effectiveness of patient mailings to promote colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2010;48(6):553–557. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbd8eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glanz K, Steffen A, Elliott T, O’Riordan D. Diffusion of an effective skin cancer prevention program: design, theoretical foundations, and first-year implementation. Health Psychol. 2005;24(5):477–487. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—August 1999. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1999. http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED433332.pdf. Published August 1999. Accessed April 10, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):91–113. doi: 10.1037/a0020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith JL, Williams JW, Jr, Owen RR, Rubenstein LV, Chaney E. Developing a national dissemination plan for collaborative care for depression. Implement Sci. 2008;3(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaney EF, Rubenstein LV, Liu CF, et al. Implementing collaborative care for depression treatment in primary care: a cluster randomized evaluation of a quality improvement practice redesign. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):121. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steckler A, Goodman RM, Kegler MC. Mobilizing organizations for health enhancement: theories of organizational change. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 335–360. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glanz K, Geller A, Shigaki D, Maddock J, Isnec MR. A randomized trial of skin cancer prevention in aquatics settings: the Pool Cool program. Health Psychol. 2002;21(6):579–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31(1):399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sequist TD, Zaslavsky AM, Colditz GA, Ayanian JZ. Electronic patient messages to promote colorectal cancer screening: a randomized, controlled trial [published online ahead of print December 13, 2010] Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):636–641. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.467. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, et al. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(9):641–651. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-9-200205070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jackson GL, Powell AA, Ordin DL, et al. VA Colorectal Cancer Care Planning Committee Members. Developing and sustaining quality improvement partnerships in the VA: the Colorectal Cancer Care Collaborative. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 1):38–43. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1155-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hall D, Dubruiel N, Elliott T, Glanz K. Linking agents’ activities and communication patterns in a study of the dissemination of an effective skin cancer prevention program. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2009;15(5):409–415. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181952178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Escoffery C, Glanz K, Hall D, Elliott T. A multi-method process evaluation for a skin cancer prevention diffusion trial. Eval Health Prof. 2009;32(2):184–203. doi: 10.1177/0163278709333154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hall DM, Escoffery C, Nehl E, Glanz K. Spontaneous diffusion of an effective skin cancer prevention program through web-based access to program materials. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(6):A125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monahan JL, Scheirer MA. The role of linking agents in the diffusion of health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):417–433. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Orlandi MA, Landers C, Weston R, Haley N. Diffusion of health promotion innovations. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1990. pp. 270–286. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. New York, NY: The Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prochaska JM, Prochaska JO, Levesque DA. A transtheoretical approach to changing organizations. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2001;28(4):247–261. doi: 10.1023/a:1011155212811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chao HH, Schwartz AR, Hersh J, et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening and care in the Veterans Affairs healthcare system. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2009;8(1):22–28. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2009.n.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Demakis JG, McQueen L, Kizer KW, Feussner JR. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI): a collaboration between research and clinical practice. Med Care. 2000;38(6) suppl 1:I17–I25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubenstein LV, Mittman BS, Yano EM, Mulrow CD. From understanding health care provider behavior to improving health care: the QUERI framework for quality improvement. Med Care. 2000;38(suppl I):I129–I141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Langley GR, MacLellan AM, Sutherland HJ, Till JE. Effect of nonmedical factors on family physicians’ decisions about referral for consultation. CMAJ. 1992;147(5):659–666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berwick DM. Quality comes home. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(10):839–843. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-10-199611150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs health care system on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(22):2218–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacDonald G, Starr G, Schooley M, Yee SL, Klimowski K, Turner K U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Introduction to Program Evaluation for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/tobacco_control_programs/surveillance_evaluation/evaluation_manual/pdfs/evaluation.pdf. Published November 2001. Accessed April 10, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bal DG, Lloyd JC, Roeseler A, et al. California as a model. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(suppl 18):69S–73S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brownson RC, Koffman DM, Novotny TE, et al. Environmental and policy interventions to control tobacco use and prevent cardiovascular disease. Health Educ Q. 1995;22(4):478–498. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang X, Cowling DW, Tang H. The impact of social norm change strategies on smokers’ quitting behaviours. Tob Control. 2010;19(suppl 1):51–55. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.029447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kotler P, Roberto N, Lee N. Social Marketing: Improving the Quality of Life. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alexander J, Prabhu Das I, Johnson TP. Time issues in multilevel interventions for cancer treatment and prevention. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;44:42–48. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]