Abstract

Background:

Body mass index (BMI) before pregnancy and weight gaining during pregnancy affect infant birth weight and are associated with unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. The aim of this study was to describe the weight gain pattern of Iranian pregnant women according to the BMI status at the beginning of pregnancy.

Methods:

This was a longitudinal cross sectional study. A total of 500 pregnant women in 6th-10th weeks of pregnancy were enrolled and followed up through delivery. Body mass index categories based on first visit weight and total weight gain were calculated. The multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to compare the mean values of gestational weight gain.

Results:

At the first care, those with underweight, normal, overweight and obese accounted for 10.7%, 46%, 35.9% and 7.4% of all participating women, respectively. Most of the subjects were in normal range of BMI (46%) at the beginning of the study. As BMI was more at the first visit, the recommended amount of weight gain was less achievable (70% versus 27%). Although the average weight gain in obese women was less than other groups (9±7.9), about 55% of them were over the recommended standards of weight gain.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, in spite of frequent visits during pregnancy, only half of pregnant women had normal weight gain and most of them had normal BMI at the first visit. This study highlights the importance of considering women with abnormal pre pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain at an increased risk and providing appropriate care for them to prevent future adverse outcomes.

Keywords: BMI, Iran, pregnancy, weight gain

INTRODUCTION

Body mass index (BMI) before pregnancy and weight gaining during pregnancy affect infant birth weight and are associated with unfavorable pregnancy outcomes.[1] Several evidence indicated that gaining weight more or less than the normal range has a determinant role in gestational outcomes and the lifelong consequences for both mother and child.[2] Insufficient weight gain is associated with preterm birth, low birth weight, growth retardation, and prematurity.[3] Whereas, extreme weight gain has been linked with large-for-gestational age, gestational diabetes, hypertensive pregnancy disorders (HPD), caesarean delivery, macrosomia, and maternal weight preservation after delivery.[4–6]

Furthermore, established obesity after delivery gradually increases the risk of cardio-vascular disease and breast cancer after the menopause.[7]

One of the most important risk modifiers of pregnancy weight gain is the weight at the beginning of pregnancy. The best available measure of pre pregnancy weight, body mass index (BMI, a measure of body fat based on weight and height), has been updated in the new guidelines to the categories and World Health Organization (WHO) recommended some cutoff points and ranges for normal weight gain for underweight, normal-weight, overweight, and obese gravitas.[8]

Recent studies indicated that only 30–40% of pregnant women gain weight within normal range[9] and weight gain in most pregnant women are not within the recommended range.

Limited studies in Iran investigated the pattern of weight gain during pregnancy. Yekta et al, studied the patterns of gestational weight gain on 270 pregnant women in urban care settings of Urmia city. This study showed that only 42.6% of subjects reached recommended weight gain.[10] Furthermore, statistics from Iran indicated the high prevalence of low birth weight and other complications of pregnancy[11,12] and an increased rate of low birth weight in rural areas of Iran.[13]

Comprehensive maternal care in Iran controls maternal weight gain during pregnancy in urban and rural areas, but limited studies have examined its actual effect in optimizing weight gain.

The aim of this study was to describe the weight gain pattern of Iranian pregnant women according to the BMI status at beginning of pregnancy.

METHODS

This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted in Isfahan health center II, Isfahan, Iran. This center covers 28 urban and 6 rural health care centers that cover a population of 1,079,717.

The eligibility criteria included pregnant women 15 to 49 years of age, without non-communicable chronic diseases (like hypertension and diabetes). Mothers with children younger than 3 years, history of abortion and still birth were not included. Exclusion criteria were gestational diabetes, pregnancy induced hypertension, eclampsia or pre-eclampsia.

Between May 2010 to March 2011, a total of 500 pregnant women in 6th-10th weeks of pregnancy, who met the eligibility criteria, were investigated.

According to national guideline of maternal care in Iran, weight status of pregnant women has been recorded eight times during pregnancy. To facilitate controlling of maternal weight gain, a monitoring chart has been employed to alert mothers and health care workers to consider susceptible deviation from recommended reference lines. According to this guideline, each woman had been taken cares in eight appointments during gestation: 6-10th gestational weeks (baseline), 16-20th weeks, 26-30th weeks, 31-34th weeks, 35-37th weeks, 38th week, 39th week and 40th week of pregnancy. The subjects were grouped based on their pre pregnancy BMI [weight (kg)/height2 (m)] to four levels: “underweight” women (BMI<19.9 kg/m2), “normal-weight” women (BMI19.9–25.0 kg/m2 and “overweight women” (BMI 25.1–30.0 kg/m2) and obese women with a pre pregnancy BMI>30.0 kg/m2. In this study, the first BMI was assumed as pre pregnancy BMI.

The baseline data of demographic and socioeconomic variables: age, education, job and parity were collected at the first visit. During the maternal visits, women were weighted at the clinic by using a digital scale. This digital scale had a minimum capacity of 0kg and maximum of 150kg, which was accurate to 0.1kg. Stature was measured with a portable stadiometer, with a maximum allowable variation of 0.5cm between the two measurements. All the anthropometric measurements were taken by trained health care workers and standardized according to recommended guidelines. Pre-gestational body mass index [BMI=weight (kg)/stature (m2)] was obtained during the first care. Clinical data such as gestational age and medical and obstetrical history were collected from their medical records. According to the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) for totalpregnancy weight gain, gestational weight gain was categorized.

The statistical analysis initially involved the description of the pregnant women participating in the study; all descriptive statistics are presented as means and standard deviations for quantitative variables, and as relative frequencies and percentage for categorical variables. The multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to compare the mean values of gestational weight gain.

The design of the study was approved in Ethics committee of Vice Chancellor for Research, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. All participants received study information and provided written informed consent. Also, the confidentiality of all information was managed carefully by researchers.

RESULTS

This was a longitudinal cross sectional study that included 494 pregnant women and followed them to the time of delivery. All participants were completed the first five visits, but 114 of them did not come to visit in the last three appointments. However, the pattern of losses was random in relation to the different variables and missing data was handled using the regression model.

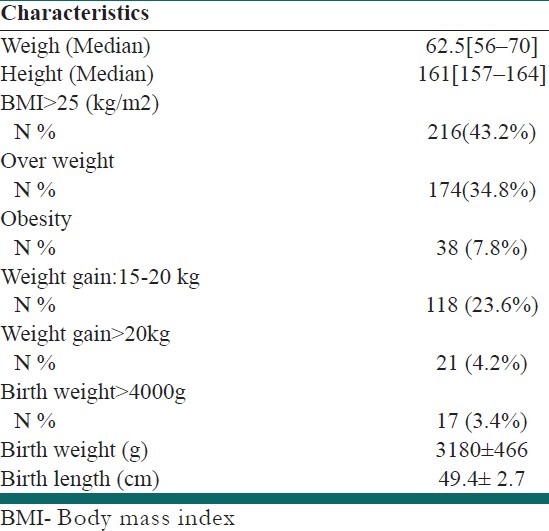

The baseline characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants

At the first care, those with underweight, normal, overweight and obese accounted for 10.7%, 46%, 34.8% and 7.8% of all participating women, respectively.

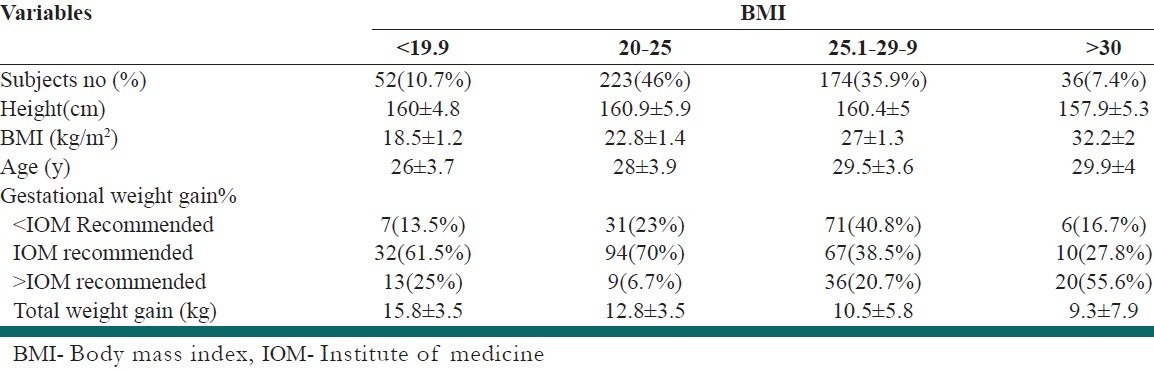

The overall mean gestational weight gain was 11.59 Kg (standard deviation, SD: 5.4). Mean and standard deviation of weight in four categories of MBI are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants according to primary BMI

As it shown in Table 1, about 27.8 % of pregnant women had weigh gain more than 15 kg. Totally, 23.5% of participant had got less, 49.5% within, 27% more than recommended weigh gain. Most of the subjects were in normal range of BMI (46%) at the beginning of the study. As BMI was more at the first visit, the recommended amount of weight gain was less achievable (70% versus 27%).

Although the average weight gain in obese people was less than other groups (9.3 ±7.9), but about 55% of them were over the recommended standards of weight gain.

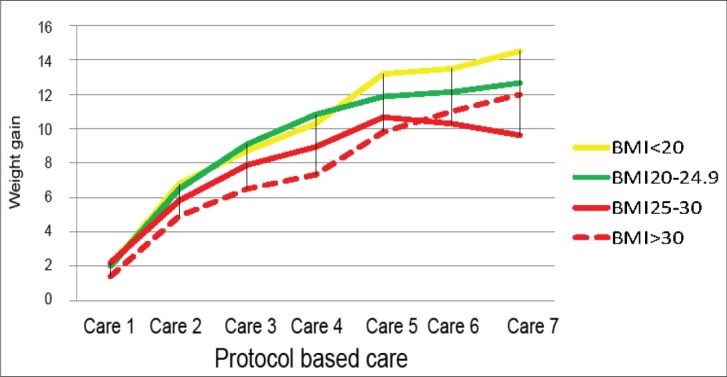

Figure 1 shows the trend of weight gaining in subjects regarding to primary BMI.

Figure 1.

Trend of weight gain regarding primary BMI

The results of MANOVA showed that weights and weight gaining during all visits are statistically different according to primary BMI.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to describe the weight gain pattern of pregnant women according to the BMI status at the beginning of pregnancy.

Our findings demonstrate that at the beginning of pregnancy, about 7.8 % and 34.8% of mothers were obese and overweight respectively, indicated that obesity and being overweight is a common phenomenon in young women in reproductive age.

In spite of the regular and planned care for pregnant women in Iran, only half of them got recommended weight during their pregnancy. It means that in our health system a considerable number of subjects start their pregnancies without meeting the standard criteria, which designed to preserve their healthy life. It shows that prenatal care in Iranian health care system is not efficiently working regarding nutritional care during pregnancy and provides unsatisfactory care.

This phenomenon was seen in other studies in different parts of world. A study in Brazil discovered that the rate of obesity in pregnant young women was 6.9%.[14] Similar study in Switzerland found it as 8.9%.[9] Another study in USA showed that 3.6 % obese and 11.3% overweight women get pregnant[15] and the rate of obesity in pregnant women in Vietnam was 8.5 %.[16] The results of our study are in line with other studies in Iran. Yazdanpanahi et al, reported that 5.3% of women were obese in the first visit of pregnancy[17] and another study in the Babol indicated this rate as 9.8%.[18]

In our study 28% of participants had a weight gain of more than 15 Kg and 4.2% of these women gained more than 20 Kg.

Additionally, overweight and obese women were not successful to manage their weigh gaining during pregnancy and 56% of them gain more than predicted weight and 17% gain less than standards of weight gaining during pregnancy. Another study in Rasht country in Iran showed that about 30% of obese and overweight women had weight gain less than predicted one.[19] Another study in USA indicated that 46% of obese and 63% of overweight women gain more than standard weight.[20] These results showed that if the weight of women before pregnancy does not manage properly, we are witnessed of inappropriate weigh gain during pregnancy and its complications.

We found that the mean of weight gaining during pregnancy was 11.9 (SD: 5.4). This rate was lowest for obese women (9.3±7.9) and was highest for underweight women (15.8± 3.5). This was 11.4 (SD: 3.2) in Rasht study[19] and 11.2 kg (SD: 4.1) in another study in Urmia Country.[10]

Considering the range of weight gaining during pregnancy and weigh gaining according to BMI categories seems to be more beneficial in this way.

The results of this study indicated that about one-quarter of pregnant women had weight gaining less than normal. Another study in Iran reported this rate as high as 80% in Rasht country.[19] This indicated that in spite of several efforts to optimize the weight gaining during pregnancy in Iran, this aim was achieved in only 50% of pregnant women and half of them are not able to get the ideal weight during pregnancy.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in spite of frequent visits during pregnancy, only half of pregnant women had normal weight gaining and most of them had normal BMI at the first visit. This study highlights the importance of considering women with abnormal pre pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain at an increased risk and providing appropriate care for them to prevent future adverse outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was founded by research chancellor of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Our heartfelt thanks are extended to all of women who so graciously agreed to participate in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siega Riz AM, Evenson KR, Dole N. Pregnancy related Weight Gain—A Link to Obesity? Nutr Rev. 2004;62:S105–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crozier SR, Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Cooper C, Harvey NC, Cole ZA, et al. Weight gain in pregnancy and childhood body composition: Findings from the Southampton Women's Survey. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1745–51. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.29128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mamun AA, O’Callaghan M, Callaway L, Williams G, Najman J, Lawlor DA. Associations of gestational weight gain with offspring body mass index and blood pressure at 21 years of age. Circulation. 2009;119:1720–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asplund CA, Seehusen DA, Callahan TL, Olsen C. Percentage change in antenatal body mass index as a predictor of neonatal macrosomia. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:550–4. doi: 10.1370/afm.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiel DW, Dodson EA, Artal R, Boehmer TK, Leet TL. Gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in obese women: How much is enough? Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:752–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000278819.17190.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunderson EP. Child bearing and obesity in women: Weight before, during, and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36:317–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2009.04.001. ix. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser A, Tilling K, Macdonald-Wallis C, Sattar N, Brion MJ, Benfield L, et al. Association of maternal weight gain in pregnancy with offspring obesity and metabolic and vascular traits in childhood. Circulation. 2010;121:2557–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.906081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds R, Osmond C, Phillips D, Godfrey K. Maternal BMI, parity, and pregnancy weight gain: Influences on off spring adiposity in young adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:5365–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frischknechta F, Brühwilera H, Raiob L, Lüschera KP. Changes in pre-pregnancy weight and weight gain during pregnancy: Retrospective comparison between 1986 and 2004. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139:52–5. doi: 10.4414/smw.2009.12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yekta Z, Ayatollahi H, Porali R, Farzin A. The effect of pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain on pregnancy outcomes in urban care settings in Urmia-Iran. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2006;6:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-6-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jafari F, Eftekhar H, Pourreza A, Mousavi J. Socio-economic and medical determinants of low birth weight in Iran: 20 years after establishment of a primary healthcare network. Public Health. 2010;124:153–8. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golestan M, Akhavan Karbasi S, Fallah R. Prevalence and risk factors for low birth weight in Yazd, Iran. Singapore Med J. 2011;52:730–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Movahedi M, Hajarizadeh B, Rahimi A, Arshinchi M, Amirhosseini K, Haghdoost AA. Trends and geographical inequalities of the main health indicators for rural Iran. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24:229–37. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seligman LC, Duncan BB, Branchtein L, Gaio DS, Mengue SS, Schmidt MI. Obesity and gestational weight gain: Cesarean delivery and labor complications. RevSaude Pública. 2006;40:457–65. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000300014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oken E, Rifas-Shiman SL, Field AE, Frazier AL, Gillman MW. Maternal gestational weight gain and offspring weight in adolescence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:999–1006. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818a5d50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ota E, Haruna M, Suzuki M, Anh DD, Tho LH, Tam NT, et al. Maternal body mass index and gestational weight gain and their association with perinatal outcomes in Viet Nam. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:127–36. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.077982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yazdanpanahi Z, Forouhari S, Parsanezhad M. Prepregnancy bodymass index and gestational weightgainand their association with some pregnancy outcomes. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2008;10:326–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yazdani S, Yosofniyapasha Y, Nasab BH, Mojaveri MH, Bouzari Z. Effect of maternal body mass index on pregnancy outcome and newborn weight. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:34. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maddah M. Pregnancy weight gain in Iranian women attending a cross-sectional study of public health centres in Rasht. Midwifery. 2005;21:365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen JN, O’Brien KO, Witter FR, Chang SC, Mancini J, Nathanson MS, et al. High gestational weight gain does not improve birth weight in a cohort of African American adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:183–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]