Abstract

Purpose

To relate costs and treatment benefits for macular edema due to diabetes (DME) and branch and central retinal vein occlusion (BRVO, CRVO).

Design

A model of resource utilization, outcomes, and cost effectiveness and utility.

Participants

none

Methods

Results from published clinical trials (index studies) of laser, intravitreal corticosteroids, intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents, and vitrectomy trials were used to ascertain visual benefit and clinical protocols. Calculations followed from the costs of one year of treatment for each treatment modality and the visual benefits as ascertained.

Main Outcome measures

Visual acuity (VA) saved, cost of therapy, cost per line saved, cost per line-year saved, and costs per quality adjusted life years (QALYs).

Results

The lines saved for DME (0.26 to 2.02), BRVO (0.74 to 4.92), and CRVO (1.2 to 3.75) yielded calculations of costs/line of saved VA for DME ($1329 to 11609), BRVO ($494 to 13039), and CRVO ($704 to 7611), costs/line-year for DME ($60 to 561), BRVO ($25 to 754), and CRVO ($45 to 473), and costs/QALY of $824 to $25566.

Conclusion

Relative costs and benefits should be considered in perspective when applying and developing treatment strategies.

Keywords: Macular edema, anti-VEGF therapy, laser photocoagulation, medical costs

Introduction

Macular edema is a common consequence of several retinal vascular diseases and may result in visual loss ranging from mild to severe. Randomized controlled trials established the efficacy of laser photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema (DME)1 and macular edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) 25 years ago,2 but concluded that while laser eliminated edema, there was no visual efficacy for macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO).3 These three collaborative, randomized, control trials have been the gold standard governing treatment and exemplify the methods and rigor with which therapeutic efficacy should be evaluated.

Periocular therapies have been evaluated with limited or no visual efficacy,4, 5 but the advent of intravitreal therapies has induced a paradigm shift.6, 7 Mechanisms of retinal vascular leakage have been better understood at a basic science level8, 9 and found to be clinically pertinent in DME, BRVO, and CRVO.10, 11 Subsequently, studies showed promising beneficial effects of intravitreal corticosteroid injections for DME,12, 13 BRVO14 and CRVO.15 These results prompted development and study of sustained release implants to deliver corticosteroids.16, 17 Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents were evaluated with encouraging results for DME,18 – 20 and macular edema secondary to BRVO21 and CRVO.22 – 24 Surgical strategies have also been reported with mixed results or for only narrow subsets of patients.25 – 27

Subsequently, several well designed and well executed (mostly randomized, control) trials have reported statistically beneficial effects of these newer therapies. The benefits delineated have generally been measured as a few letters rather than several lines, and characteristically require ongoing treatment to maintain these modest benefits. Thus, the relatively low magnitude of the visual acuity differences, the high prevalence of these conditions, the relatively high treatment costs, and the high treatment burden for an individual patient raise cost-benefit questions on a personal and systemic level. Historically, clinicians are not inclined to consider dollar costs versus benefits of treatment, but as the options and their costs escalate, this issue looms larger.

The purpose of this study is to estimate the costs involved in representative therapeutic regimens for each of the three etiologic categories of macular edema by tabulating absolute cost per line of vision saved, and cost per line-year of vision saved.

Materials and Methods

A similar methodology as previously reported28, 29 was applied in this study. For each of the three diagnostic groups (DME, BRVO, CRVO) an index study (usually a collaborative, randomized, controlled study with 6 month to 1 year follow-up information) was chosen for natural history,1,3 focal laser,1 – 3 intravitreal triamcinolone (IVTA),30 – 32 intravitreal dexamethasone implant,33, 34 pegaptanib,18, 35,36 bevacizumab,21, 37, 38 and ranibizumab,39 – 41 and a surgical series for DME only42 (Table 1, available at http://aaojournal.org). A resource utilization protocol was constructed and priced for an initial year of treatment for each diagnostic group, and the lines of visual acuity saved were estimated. The lines saved was calculated and defined as lines gained added to (or subtracted from) lines that would otherwise be expected to have been lost (or gained) without treatment. Lines were calculated by dividing “letters” by 5, when index studies reported results as such. Generally, the more favorable outcome was chosen from differently dosed subgroups. All visual benefits were assumed to be durable for the lifetime of the patient. The natural history estimate was used to adjust treatment benefits when internal natural history controls were lacking from the index study.

The treatment and ancillary test protocol schedules were deduced from each index study, but were “downsized” to reflect a more likely application in a non-study, clinic setting. The visit, treatment, and likely ancillary test schedules were adapted from the respective index study protocols to reflect a lesser reliance on fluorescein angiography and the wider usage of optical coherence tomography (OCT). A level 4 new patient initial examination and a level 3 follow-up examination for each subsequent visit were assumed for cost calculations. Most index studies offered one-year follow-up data, but resource utilization data were conservatively extrapolated to one year when shorter, assuming a durable result at one year, and until death for line-year calculations. Explanatory comments specify relevant assumptions in constructing estimates and appear in Appendix 1 (available at http://aaojournal.org). By design, costs were generally underestimated and benefits were overestimated for more expensive modalities; the converse was applied to less expensive modalities.

The Medicare allowable amounts for hospital-based utilization (in South Florida as of June 1, 2010) were applied as costs (including hospital facility usage allowable) for the hypothetical one year of treatment.43, All costs were calculated in US dollars; present value adjustments were not included in cost calculations.

Using the estimate of lines saved, cost/line saved was calculated. The mean age of each study cohort was used to calculate a life expectancy by consulting the actuarial table of the Social Security Administration44 and used to calculate cost/line years saved.

A cost utility analysis was performed by using the lines saved estimate and ascribing 0.03 marginal qualtity adjusted life-years (QALYs) for each line gained, a reasonable estimate from previously published data in the visual acuity range of the index study cohorts, albeit for a “better eye” which was not usually the case in the index study cohorts.45

Results

A detailed discussion of the assumptions upon which visual acuity benefit and treatment protocols were based is included in Appendix 1 (available at http://aaojournal.org). Calculated costs, cost/line saved and cost/line-year saved calculations are listed only in the Tables 1–4 (Table 1, available at http://aaojournal.org).

Diabetic Macular Edema

The untreated, natural history was calculated to be a 0.42 line loss.1 Laser treatment resulted in only a 0.16 line loss, thus offered a 0.26 lines saved (treatment benefit) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Utilization, Treatment Protocol, Costs for 1 year, Costs/line saved, and Costs/line-year saved for Diabetic Macular Edema

| f/u visits | OCTs | FA | treatments | cost ($) | Lines Saved | Dollars per line saved | Mean age (yrs.) | Dollars per line-year saved | Dollars per QALY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Laser1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1326 | 0.26 | 5099 | 52 | 176 | 5862 |

| Intravitreal Triamcinolone30 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2.3 | 1574 | 0.42 | 3749 | 63 | 188 | 6246 |

| Dexamethasone Implant33 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1* | 2207 | 0.4 | 5666 | 63 | 285 | 9446 |

| Pegaptanib18 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 10500 | 1.00 | 10500 | 62 | 507 | 16667 |

| Bevacizumab | ||||||||||

| PACORES37 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 2684 | 2.02 | 1329 | 60 | 60 | 2013 |

| BOLT 46 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 4718 | 2.1 | 2246 | 65 | 125 | 4160 |

| Ranibizumab | ||||||||||

| DRCR39 | 11 | 8 | 0 | 8.5 | 21265 | 1.46 | 11372 | 63 | 549 | 23119 |

| READ47 | 11 | 12 | 0 | 8 | 21709 | 1.79 | 11609 | 62 | 561 | 19251 |

| Vitrectomy42 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4701 | 1.43 | 3287 | 66 | 183 | 8706 |

Each patient was assumed to have a level 4 new patient examination.

longer follow-up might require 2 implants (and substantially higher costs)

f/u = follow-up

OCT = optical coherence tomography

FA = fluorescein angiography

DRCR= Diabetic retinopathy clinical research network

READ = Ranibizumab of edema of the macular in Diabetes Study

BOLT = Bevacizumab or Laser Therapy in the management of Diabetic Macular Edema

PACORES = Pan American Collaborative Retina Study

QALY= quality adjusted life year

Intravitreal triamcinolone was reported to offer no meaningful difference from focal grid laser treatment, but reported data supported a 0.42 lines saved (treatment benefit) estimate.

The dexamethasone implant’s benefit was derived from the 90 day data in Figure 1 in its index study33 for the 0.7mg group to be 0.40 lines saved compared to its internal natural history control group. Results were extrapolated to one year fully recognizing the probability that at least a second implant might be commonly deployed (at about a 35% higher cost).

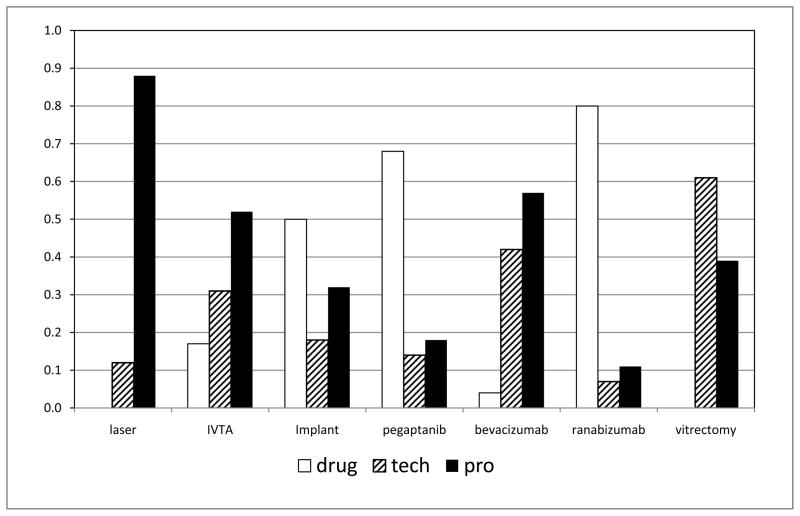

Figure 1.

Graph showing mean proportional costs of professional fees (pro), technical (tech), and, drug costs for the options of diabetic macular edema, branch retinal vein occlusion, central retinal vein occlusion. The two sets of columns of data for bevacizumab results are from the Pan American Collaborative Retina Study (PACORES) and Bevacizumab or Laser Therapy in the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema Study, Report #2 (BOLT-2), and the ranibizumab data are from the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research (DRCR) study and Ranibizumab of Edema of the Macular in Diabetes Study, Report #2 (READ-2). Vitrectomy data is for treatment of diabetic macular edema only. (IVTA= intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide)

Pegaptanib benefits were calculated based on the index study18 to be 2.02 lines saved. Bevacizumab calculations based on the index study37 yielded 2.02 lines saved. Another study Bevacizumab or Laser Treatment in the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema Study (BOLT-2)46 yielded similar visual benefits, but more injections and thus approximately 75% higher costs.

Ranibizumab calculations based on the index study39 yielded 1.46 lines saved, remarkably similar to results deduced from the separate Ranibizumab for Edema of the mAcula in Diabetes (READ-2) trial.47

Vitrectomy for a cohort with demonstrable preretinal traction42 yielded 1.43 lines saved.

Macular Edema Associated with Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion

The natural history of BRVO was calculated as 0.23 lines (1.15 letters) spontaneous improvement2 and was utilized as the natural history adjustment when internal controls were lacking in other index studies (Table 3). A comprehensive review concluded a similar value.48

Table 3.

Utilization, Treatment Protocol, Costs for 1 year, Costs/line saved, and Costs/line-year saved for Macular Edema Associated with Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion.

| f/u visits | OCTs | FA | treatments | cost ($) | Lines Saved | Dollars per line saved | Mean age (yrs) | Dollars per line-year saved | Dollars per QALY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Laser2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1.43 | 1692 | 1.1 | 1539 | 55 | 58 | 1572 |

| Intravitreal corticosteroid31 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 2.2 | 1583 | 1.40 | 1131 | 67.4 | 67 | 2217 |

| Dexamethasone Implant34 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1* | 2212 | 0.74 | 2990 | 64.8 | 162 | 5536 |

| Pegaptanib35 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 7.3 | 12540 | 2.57 | 4898 | 7.4 | 405 | 13554 |

| Bevacizumab21 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 4.3 | 2432 | 4.92 | 494 | 63.5 | 25 | 824 |

| Ranibizumab40 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 11.4 | 28685 | 2.20 | 13039 | 66.5 | 754 | 25566 |

Each patient was assumed to have a level 4 new patient examination

longer follow-up might require 2 implants

f/u = follow-up

OCT = optical coherence tomography

FA = fluorescein angiography

QALY= quality adjusted life year

The index study for laser treatment2 yielded a 1.33 line (6.65 letters) improvement for laser, which when reduced by the natural history adjustment yielded 1.1 lines (5.5 letters) saved.

The IVTA index study31 yielded 1.4 lines saved. The dexamethasone treatment benefit using similar assumptions as with DME was calculated to be 0.74 lines saved. Lines saved values were calculated for pegaptanib35 (2.57), bevacizumab21 (4.92), and ranibizumab (2.20)40.

Macular Edema Associated with Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

The non-ischemic natural history group of the Central Vein Occlusion Study (CVOS)49 lost approximately 0.6 line which was used as a natural history adjustment whenever studies lacked a sham or untreated group (Table 4). This value was consistent with a recent natural history meta-analysis.50

Table 4.

Utilization, Treatment Protocol, Costs for 1 year, Costs/line saved, and Costs/line-year saved for Macular Edema Associated with Central Retinal Vein Occlusion.

| f/u visits | OCTs | FA | treatments | cost ($) | Lines Saved | Dollars per line saved | Mean age | Dollars per line-year saved | Dollars per QALY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intravitreal corticosteroid32 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 2.1 | 1536 | 2.18 | 704 | 67.5 | 45 | 1468 |

| Dexamethasone Implant34 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2359 | 1.2 | 1961 | 75 | 172 | 5957 |

| Pegaptanib36 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 13638 | 2.62 | 5205 | 64 | 273 | 9132 |

| Bevacizumab38 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 8.1 | 4409 | 3.75 | 1176 | 63.7 | 80 | 2613 |

| Ranibizumab41 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 8.7* | 21464 | 2.82 | 7611 | 68 | 473 | 15867 |

longer follow-up might require 2 implants

f/u = follow-up

OCT = optical coherence tomography

FA = fluorescein angiography

QALY= quality adjusted life year

The calculated lines saved values for each modality were IVTA (2.18)32, dexamethasone implant (1.2)34, pegaptanib (2.62)36, bevacizumab (3.75), and ranibizumab (2.82)41. Laser treatment was not shown to be visually useful for macular edema, so it is not considered.

Cost-Utility Analysis

The results are included in Tables 2, 3, and 4 and follow mathematically from the lines saved, costs, life expectancy, and the assumption that 0.03 QALYs was equated with a line of vision saved in the range of the index study cohorts45. The ranges of values are similarly broad as for other cost parameters.

Proportion of costs in delivery of various therapies

The costs of treatment were apportioned to pharmacologic, technical, and professional fees for each treatment option for one year of initial treatment. These were averaged across all three diagnostic groups for simplicity of analysis (Figure 1). The proportion of costs per category ranged from 88% professional fee and no pharmaceutical costs for laser-based treatments, to 80% pharmaceutical costs and 11% professional fees for intravitreal ranibizumab treatments.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the wide range of cost parameters for macular edema treatment ranging from a low of $1,326 for laser to $23,119 for a one year course of ranibizumab treatment, a 17-fold difference; costs/line-year ranged from $25 to $754. For comparison, a similar methodology published previously found costs/line-year to range from $21 (laser for proliferative diabetic retinopathy) and $33 (scleral buckling) to $1248 for pegaptanib treatment for age-related macular degeneration.28

The pharmacotherapeutic era has provided many more treatment options for macular edema due to three of its principal causes: DME, BRVO, and CRVO. A dizzying flurry of clinical trial results has been recently released leaving many clinicians with varying degrees of skepticism, unanswered questions, and confusion regarding optimal treatment algorithms. The formidable costs of many treatment options have introduced additional concerns and highlight financial repercussions of what might be only marginal differences in management regimens. In the absence of disparate treatment benefits, a natural conclusion would be to consider less costly and lower patient treatment burden options.

A principal limitation in an analysis of this question is the non-standard endpoint across each of the index studies; some measured mean letter changes while some studied the rate of reaching thresholds of changes in Snellen letters. The current study required certain assumptions to deduce the “lines saved” from these data. This would not seem to be a serious limitation since the magnitude of the uncertainty of visual benefit calculations is so much less than the magnitude of the variation in cost estimates. Furthermore, the magnitude of the visual treatment benefits appears to be relatively small, a line or two and frequently less, even though statistically significant. Certainly, selection biases and application differences may apply not only to the index study patient cohorts but, more importantly, to the patients actually treated in the clinic based on the results of these studies. Thus, the “real world” differential may be even less. Furthermore, most index studies report up to one year results – the durability and amount of additional costs necessary to maximize longer term results is even more conjectural. In fact, in the case of intravitreal corticosteroid injections, the initially encouraging results in a randomized study had disappeared by a one year follow-up study.30 Most studies offer impressive anatomic benefits (marked reduction of retinal thickening on OCT), but the typical clinician’s intuition is that the visual effects are not as impressive, and even the anatomic benefits often diminish with longer duration of therapy.

The current study has purposely considered a conservatively low estimate of costs and a high assessment of benefit for the more expensive of these therapies, and the opposite for the less expensive options. Moreover, only one year of costs has been factored in and nonnegligible costs incurred in the event of complications (infections, cataracts, glaucoma) have not been factored into cost estimates. Similarly, costs (or savings) incurred in considering sequential or combination treatments were beyond the scope of the current cost model. In addition, costs of travel, lost work opportunity, and time spent following follow-up recommendations are not included in these analyses. Hence, real cost/benefit differentials are probably higher than reported herein.

As for age-related macular degeneration (AMD) studies the decision as to when to initiate treatment has turned out to be much easier than the decisions as to when discontinue. Perhaps “as needed” or combination protocols will define cogent treatment guidelines for macular edema. The dilemma of how to determine efficacy or, more importantly, utility is compounded by the fact that DME populations are generally younger than age-related macular degeneration cohorts and may be considered for treatment and incur high costs for much longer. Moreover, a diabetic patient may be more likely to have co-existing cardiovascular disease which may raise concern regarding long term cardiovascular toxicities of anti-VEGF treatments.51 The converse, however, is that longer post-treatment life expectancy in younger treatment cohorts enhances the compounded benefit of otherwise marginal differences, especially considering work loss limitations.52 Thus, this analysis should not be construed to ignore the costs of not gaining useful, productive degrees of visual acuity, especially for the more commonly bilaterally affected DME patient.

A related question is whether a line (or less) of visual acuity improvement reported in various studies as statistically different actually represents a worthwhile functional improvement. Every clinician recognizes that visual acuity, while representing the gold standard of outcome, may not always accurately describe a patient’s level of visual function. Accordingly, quality of life studies involving measurement of functional benefits must also be considered as they have for age-related macular degeneration. 53 Such evaluations for the conditions under study in this report were very limited.40, 41 The clinician’s intuition that a difference of one line of vision is of limited notice to a patient, or even outside of the variation of the accuracy of how visual acuity is measured, may be important when such high medical resources and treatment burdens are being committed. A crude cost-utility tabulation indicates a range of QALY costs from $1466 to $25566, all considered within the acceptable cost range45, but subject to the assumption of the study eye being the better seeing eye, an assumption probably only accurate for DME.

Another observation is that, as for AMD29, pharmacologic-based treatments invert the relative proportion of where the health care dollar is spent much more for pharmacologic and much less for professional fees. The model in the current study was based on a hospital-based practice fee schedule. If an office-based practice was used in the model, the technical costs would be added to professional fees, but reduced in aggregate, so the drug cost proportion would be higher. This inversion has important implications for policy strategies designed to contain costs - reductions in professional fees have less impact on the bottom line of the payor.

While physicians have historically been committed to making treatment decision independent of treatment costs, at least for distinctly important medical problems, the 15+ - fold cost differences, the high prevalence of these conditions, and the ongoing nature of treatment make the facing the issue of costs inescapable. It would seem good stewardship for the physician, the traditional gate-keeper of medical care, to be cognizant of the magnitude of the cost differential and to consider it in some manner in formulating treatment regimens. A problem is that there is no policy basis, or even short term motivation for the physician to act upon these findings. This difficult ethical problem is even more difficult for an individual patient, payor, or health policy maker.

In conclusion, this study confirms the intuitive assessment that the costs incurred in pharmacologic-based treatment can be unprecedentedly expensive even when considering only one year of initial therapy. The differences in visual acuity reported by recent studies may be statistically important, but their magnitude may not be as functionally beneficial, yet are driving treatment standards into an expensive and burdensome direction. Individual clinicians as well as designers of healthcare systems should be cognizant of these dilemmas before deserting less costly alternatives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported NIH center grant P30-EY014801, unrestricted grant to Bascom Palmer Eye Institute from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Footnotes

The author does not have any financial interests to disclose.

This article contains online-only material. The following should appear online-only: Table 1 and Appendix 1.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study report number 1. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:1796–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branch Vein Occlusion Study Group. Argon laser photocoagulation for macular edema in branch retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98:271–82. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evaluation of grid pattern photocoagulation for macular edema in central vein occlusion: the Central Vein Occlusion Study Group M report. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1425–33. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30849-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin JM, Chiu YT, Hung PR, Tsai YY. Early treatment of severe cystoid macular edema in central retinal vein occlusion with posterior sub-Tenon triamcinolone acetonide. Retina. 2007;27:180–9. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000237584.56552.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakano S, Yamamoto T, Kirii E, et al. Steroid eye drop treatment (difluprednate ophthalmic emulsion) is effective in reducing refractory diabetic macular edema. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:805–10. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1316-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. ANCHOR Study Group. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. MARINA Study Group. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts WG, Palade GE. Increased microvascular permeability and endothelial fenestration induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2369–79. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonetti DA, Barber JA, Hollinger LA, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces rapid phosphorylation of tight junction proteins occludin and zonula occluden 1: a potential mechanism for vascular permeability in diabetic retinopathy and tumors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23463–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen QD, Tatlipinar S, Shah SM, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a critical stimulus for diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:961–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campochiaro PA, Hafiz G, Shah SM, et al. Ranibizumab for macular edema due to retinal vein occlusions: implication of VEGF as a critical stimulator. Mol Ther. 2008;16:791–9. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonas JB, Sofker A. Intraocular injection of crystalline cortisone as adjunctive treatment of diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:425–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan CK, Mohamed S, Lee VY, et al. Intravitreal dexamethasone for diabetic macular edema: a pilot study. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010;41:26–30. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20091230-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonas JB, Akkoyun I, Kamppeter B, et al. Branch retinal vein occlusion treated by intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:65–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonas JB, Kreissig I, Degenring RF. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide as treatment of macular edema in central retinal vein occlusion. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:782–3. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuppermann BD, Blumenkranz MS, Haller JA, et al. Dexamethasone DDS Phase II Study Group. Randomized controlled study of an intravitreous dexamethasone drug delivery system in patients with persistent macular edema. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:309–17. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campochiaro PA, Hafiz G, Shah SM, et al. Famous Study Group. Sustained ocular delivery of fluocinolone acetonide by an intravitreal insert. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1393–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macugen Diabetic Retinopathy Study Group. A phase II randomized double-masked trial of pegaptanib, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor aptamer, for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam DS, Lai TY, Lee VY, et al. Efficacy of 1.25 mg versus 2. 5 mg intravitreal bevacizumab for diabetic macular edema: six-month results of a randomized controlled trial. Retina. 2009;29:292–9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31819a2d61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chun DW, Heier JS, Topping TM, et al. A pilot study of multiple intravitreal injections of ranibizumab in patients with center-involving clinically significant diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1706–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu L, Arevalo F, Berrocal MH, et al. Comparison of two doses of intravitreal bevacizumab as primary treatment for macular edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusions: results of the Pan American Collaborative Retina Study Group at 24 months. Retina. 2009;29:1396–403. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181bcef53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Priglinger SG, Wolf AH, Kreutzer TC, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab injections for treatment of central retinal vein occlusion: six-month results of a prospective trial. Retina. 2007;27:1004–12. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3180ed458d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iturralde D, Spaide RF, Meyerle CB, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment of macular edema in central retinal vein occlusion: a short-term study. Retina. 2006;26:279–84. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouvas A, Petrou P, Vergados I, et al. Intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis) for treatment of central retinal vein occlusion: a prospective study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:1609–16. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1138-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis HL, Abrams GW, Blumenkranz MS, Campo RV. Vitrectomy for diabetic macular traction and edema associated with posterior hyaloidal traction. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:753–9. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31901-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opremcak EM, Bruce RA. Surgical decompression of branch retinal vein occlusion via arteriovenous crossing sheathotomy: a prospective review of 15 cases. Retina. 1999;19:1–5. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199901000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Opremcak EM, Bruce RA, Lomeo MD, et al. Radial optic neurotomy for central retinal vein occlusion: a retrospective pilot study of 11 consecutive cases. Retina. 2001;21:408–15. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smiddy WE. The relative cost of a line of vision in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:847–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smiddy WE. Economic implications of current age-related macular degeneration treatments. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:481–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) Three-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing focal/grid photocoagulation and intravitreal triamcinolone for diabetic macular edema. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:245–51. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SCORE Study Research Group. A randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of intravitreal triamcinolone with standard care to treat vision loss associated with macular edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion: the Standard Care vs Corticosteroid for Retinal Vein Occlusion (SCORE) Study report 6. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1115–28. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SCORE Study Research Group. A randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of intravitreal triamcinolone with observation to treat vision loss associated with macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: the Standard Care vs Corticosteroid for Retinal Vein Occlusion (SCORE) study report 5. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1101–14. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haller JA, Kuppermann BD, Blumenkranz MS, et al. Dexamethasone DDS Phase II Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of an intravitreous dexamethasone drug delivery system in patients with diabetic macular edema. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:289–96. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haller JA, Bandello F, Belfast R, Jr, et al. OZURDEX GENEVA Study Group. Randomized sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone implant in patients with macular edema due to retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1134–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wroblewski JJ, Wells JA, III, Gonzales CR. Pegaptanib sodium for macular edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:147–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wroblewski JJ, Wells JA, III, Adamis AP, et al. Pegaptanib in Central Retinal Vein Occlusion Study Group. Pegaptanib sodium for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:374–80. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arevalo JF, Sanchez JG, Fromow-Guerra J, et al. Pan-American Collaborative Retina Study Group (PACORES) Comparison of two does of primary intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for diffuse diabetic macular edema: results from the Pan-American Collaborative Retina Study Group (PACORES) at 12-month follow-up. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:735–43. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-1034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu L, Arevalo JF, Berrocal MH, et al. Comparison of two doses of intravitreal bevacizumab as primary treatment for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusions: results of the Pan American Collaborative Retina Study Group at 24 months. Retina. 2010;30:1002–11. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181cea68d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, et al. Diabetic Retinopathy Research Network. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1064–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campochiaro PA, Heier JS, Feiner L, et al. BRAVO Investigators. Ranibizumab for macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion: six-month primary end point results of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1102–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown DM, Campochiaro PA, Singh RP, et al. CRUISE Investigators. Ranibizumab for macular edema following central retinal vein occlusion: six-month primary end point results of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1124–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Writing Committee on behalf of the DRCR net. Vitrectomy outcomes in eyes with diabetic macular edema and vitreomacular traction. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1087–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medicare Program: Changes to the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System and CY 2010 Payment Rates; Changes to the Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment System and CY 2010 Payment Rates. [Accessed December 11, 2010.];Federal Register. 2009 74(223):60854, 60817, 60895–60901. Available at: http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2009/pdf/E9-26499.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.United States Social Security Administration Online. [Accessed August 25, 2010.];Actuarial Publications. Period Life Table. 2006 Available at: http://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html.

- 45.Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, Landy J. Health care economic analyses and value-based medicine. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:204–23. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michaelides M, Kaines A, Hamilton RD, et al. A prospective randomized trial of intravitreal bevacizumab or laser therapy in the management of diabetic macular edema (BOLT Study): 12-month data: report 2. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1078–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen QD, Shah SM, Heier JS, et al. READ-2 Study Group. Primary end point (six months) results of the Ranibizumab for Edema of the mAcula in Diabetes (READ-2) study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rogers SL, McIntosh RL, Lim L, et al. Natural history of branch retinal vein occlusion: an evidence-based systematic review. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1094–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Central Vein Occlusion Study Group. Natural history and clinical management of central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:486–91. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150488006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McIntosh RL, Rogers SL, Lim L, et al. Natural history of central retinal vein occlusion: an evidence-based systematic review. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dafer RM, Schneck M, Friberg TR, Jay WM. Intravitreal ranibizumab and bevacizumab: a review of risk. Semin Ophthalmol. 2007;22:201–4. doi: 10.1080/08820530701543024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Javitt JC, Canner JK, Frank RG, et al. Detecting and treating retinopathy in patients with type I diabetes mellitus: a health policy model. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:483–94. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32573-3. discussion 494–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clemons TE, Chew EY, Bressler SB, McBee W AREDS Research Group. National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS): AREDS report no. 10. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:211–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.