Abstract

The synthesis and characterization of a new water-soluble N,N-chelating iminophosphorane ligand TPA=N-C(O)-2-NC5H4 (N,N-IM) (1) and its d8 (AuIII, PdII and PtII) coordination complexes are reported. The structures of cationic [AuCl2(N,N-IM)] ClO4 (2) and neutral [MCl2(N,N-IM)] M = Pd (3), Pt(4) complexes were determined by X-ray diffraction studies or by means of density-functional calculations. While the Pd and Pt compounds are stable in mixtures of DMSO/H2O over 4 days, the gold derivative (2) decomposes quickly to TPA=O and previously reported neutral gold(III) compound [AuCl2(N,N-H)] 5 (containing the chelating N,N- fragment HN-C(O)-2-NC5H4). The cytotoxicities of complexes 2–5 were evaluated in vitro against human Jurkat-T acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells and DU-145 human prostate cancer cells. Pt (4) and Au compounds (2 and 5) are more cytotoxic than cisplatin to these cell lines and to cisplatin-resistant Jurkat sh-Bak cell lines and their cell death mechanism is different from that of cisplatin. All the compounds show higher toxicity against leukemia cells when compared to normal human T-lymphocytes (PBMC). The interaction of the Pd and Pt compounds with calf thymus and plasmid (pBR322) DNA is different from that of cisplatin. All compounds bind to human serum albumin (HSA) faster than cisplatin (measured by fluorescence spectroscopy). Weak and stronger binding interactions were found for the Pd (3) and Pt (4) derivatives by isothermal titration calorimetry. Importantly, for the Pt (4) compounds the binding to HSA was reversed by addition of a chelating agent (citric acid) and by a decrease in pH.

Keywords: cytotoxic, leukemia, prostate cancer, iminophosphoranes, water-soluble, platinum, palladium, gold

1. Introduction

Cisplatin combination chemotherapy is the cornerstone of treatment for many cancers. Cisplatin and the follow-on drugs carboplatin and oxaliplatin are used to treat 40–80% of cancer patients [1]. The high effectiveness of cisplatin in the treatment of several types of tumors is severely hindered by some clinical problems such as normal tissue toxicity and the frequent occurrence of initial and acquired resistance to the drug [1–5]. A growing number of so-called “cisplatin rule-breaker” compounds have been reported [3–5] along with some Pt(IV) pro-drugs that can be photoactivated by visible light [7]. These findings have paved the way for studying other metal-based chemotherapeutic compounds [3] including relevant examples of gold [9], palladium [10], titanium [11], ruthenium [12], osmium [13] and iron complexes [14].

We and others have reported on the biological [15–18] and catalytic [19–21] applications of iminophosphorane or iminophosphine derivatives of gold(III) (selected examples in Fig. 1) [15,16]. The main advantage of iminophosphorane ligands is that they provide a C,N- or N,N-backbone that stabilizes the resulting square-planar d8 transition metal complex. An extra advantage is that the P atom in the PR3 fragment can be used as a “spectroscopic marker” to study the in vitro stability (and oxidation state) by 31P{1H} NMR [16]. Gold(III) organometallic complexes (with a pincer C,N-iminophosphorane ligand) displayed a high cytotoxicity in vitro against human ovarian cancer and leukemia cell lines while being less toxic to normal T-lymphocytes by a mode of action different from that of cisplatin [15,16]. The compounds did not interact with DNA [15]. ROS (reactive oxygen species) production at the mitochondrial level was a critical step in the cytotoxic effect of these compounds [15]. We wanted to increase the hydrophilicity of this type of IM (iminophosphorane) ligands and also to explore the biological activity of other d8 metal (Pd(II) and Pt(II)) IM complexes. We envisioned an iminophosphorane N,N- chelating ligand as an ideal platform to confer stability to d8 transition metal centers while simplifying the synthetic steps required to prepare organometallic compounds (avoiding transmetallation for metals not prone to easy C-H bond activation). We had used such a strategy to prepare gold(III) coordination catalysts for C-C and C-heteroatom bond formation [20]. The challenge here was the incorporation of a water-soluble phosphine in the skeleton of the ligand since it is well known that IMs in contact with water or polar solvents break down to the corresponding amine and phosphine oxide [22].

Fig. 1.

Examples of selected iminophosphorane organogold(III) complexes with cytotoxic properties prepared by our group. [13] ROS production at the mitochondrial level was a critical step in the cytotoxic effect of these compounds. [13a]

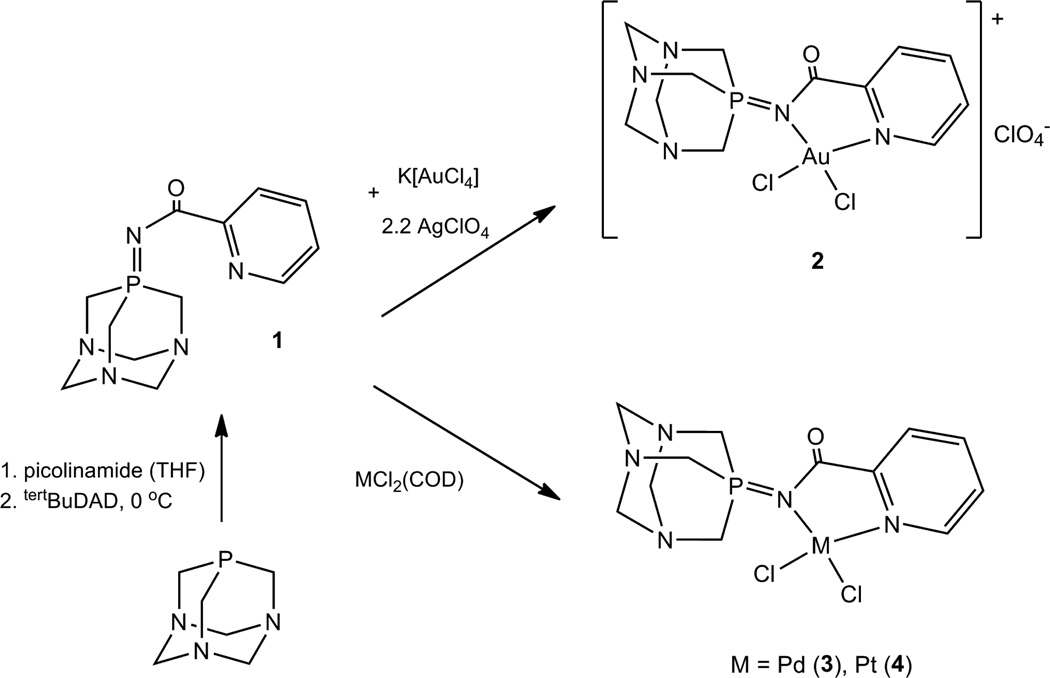

By the use of a picolinamide and water-soluble TPA (1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane) phosphine through the Pomerantz method [23], we prepared a stabilized water-soluble N,N-chelating iminophosphorane ligand TPA=N-C(O)-2-NC5H4 1 (Scheme 1). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first water-soluble iminophosphorane reported. We describe here the preparation (Scheme 1), characterization, stability in solution and study of the cytotoxic properties in vitro of its coordination complexes containing Au(III), Pd(II) and Pt(II) centers. The study of the interactions of these complexes with different biomolecules (DNA and Human Serum Albumin HSA) is also reported and compared to that of cisplatin.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of d8 metal coordination complexes containing new chelating ligand TPA=N-C(O)-2-NC5H4 (N,N-IM) 1.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Methods

All manipulations involving air-free syntheses were performed using standard Schlenk-line techniques under an argon atmosphere or in a glove-box MBraun MOD System. Solvents were purified by use of a PureSolv purification unit from Innovative Technology, Inc. The phosphine substrate TPA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, K[AuCl4], PtCl2 and AgClO4 were purchased from Strem chemicals and used without further purification. [PdCl2(COD)] [24] and [AuCl2(HN-C(O)-2-NC5H4)] 5 [25] were prepared as previously reported. NMR spectra were recorded in a Bruker AV400 (1H NMR at 400MHz, 13C NMR at 100.6 MHz, 31P NMR at 161.9 MHz). Chemical shifts (δ) are given in ppm using CDCl3, d6-DMSO or D2O as solvent, unless otherwise stated. 1H and 13C chemical shifts were measured relative to solvent peaks considering TMS (tetramethylsilane) = 0 ppm; 31P{1H} was externally referenced to H3PO4 (85%). Infrared spectra (4000-250 cm−1) were recorded on a Nicolet 6700 FT-IR spectrophotometer on KBr pellets. Elemental analyses were performed on a Perkin Elmer 2400 CHNS/O Analyzer, Series II. Mass spectra HR-ESI (High-resolution electrospray ionization) or MALDI (Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization) were performed on an Agilent Analyzer or a Bruker Analyzer. Conductivity was measured in an OAKTON pH/conductivity meter in CH3CN solution (10−3M). Circular Dichroism spectra were recorded using a Chirascan CD Spectrometer equipped with a thermostated cuvette holder. Electrophoresis experiments were carried out in a Bio-Rad Mini sub-cell GT horizontal electrophoresis system connected to a Bio-Rad Power Pac 300 power supply. Photographs of the gels were taken with an Alpha Innotech FluorChem 8900 camera. Fluorescence intensity measurements were carried out on a PTI QM-4/206 SE Spectrofluorometer (PTI, Birmingham, NJ) with right angle detection of fluorescence using a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette. ITC measurements were carried out at 25.0 (±0.2) °C on a MicroCal VP-ITC calorimeter.

2.2. Synthesis

TPA=N-C(O)-2-NC5H4 (N,N-IM) (1)

TPA (0.157 g, 1.0 mmol) and picolinamide (0.122 g, 1.0 mmol) were placed in a Schlenk flask under nitrogen. Dry, degassed THF (15 mL) was added and to this solution, tBuDAD (0.230 g, 1.0 mmol) in dry and degassed THF (4 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C. The reaction was left stirring at RT for 15 hours. After this period, the yellow reaction mixture was colourless with some white precipitate. The solvent was reduced in vacuo to a minimum (< 2 mL) and Et2O (10 mL) was added, giving a white solid that was filtered and dried in vacuo. Yield: 0.254 g (93%). Anal. Calcd for C12H16N5OP (277.11): C, 51.98; H, 5.82; N, 25.26. Found: C, 51.76; H, 5.79; N, 25.24. MS (ESI+) [m/z]: 278.12 [M]+. 31P{1H} NMR: δ −29.4 (s, CDCl3), −31.4 (s, DMSO-d6), − 24.8 (s, D2O). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.68 (1H, d, 3JHH 4 Hz, NCH), 8.10 (1H, d, 3JHH 8 Hz, C(O)CCH), 7.75 (1H, t, 3JHH 8 Hz, C(O)CCHCH), 7.37 (1H, t, 3JHH 7 Hz, NCHCH), 4.35 (6H, d, 2JPH 8 Hz, PCH2N), 4.42 (AB system, 6H, NCH2N). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3): δ 177.7 (s, C=O), 152.0 (s, C(O)C(N)(CH)), 149.1 (s, NCH), 136.7 (s, C(O)CCHCH), 125.4 (s, NCHCH), 123.5 (s, C(O)CCH), 72.8 (d, JPC 9 Hz, NCH2N), 52.7 (d, JPC 46 Hz, PCH2N). IR (cm−1): ν 1582 (C=O), 1360 (P=N).

[AuCl2(N,N-IM)]ClO4 (2)

To K[AuCl4] (0.057 g, 0.15 mmol) in dry MeCN (10 mL), AgClO4 (0.068 g, 0.33 mmol) in dry MeCN (2 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred in the dark for 30 min, after which it was filtered through Celite (to remove AgCl). 1 (0.042 g, 0.15 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) was added and the yellow solution became instantly brown. After 50 min stirring, the reaction mixture was again filtered through celite (to remove KClO4) and then the solvent was reduced in vacuo to a minimum. Upon addition of Et2O (10 mL), a red-brown solid was obtained, which was washed with MeCN (<1 mL at a time) and Et2O and dried in vacuo. Yield: 0.050 g (52%). MS (HR-ESI+) [m/z]: 544.0126 [M]+. 31P{1H} NMR: δ 6.5 (s, DMSO-d6), 5.7 (s, CD3CN). 1H NMR (CD3CN): δ 9.39 (1H, d, 3JHH 6 Hz, NCH), 8.60 (1H, t, 3JHH 8 Hz, C(O)CCHCH), 8.19 (2H, m, C(O)CCH + NCHCH), 5.08 (6H, 2JPH 10 Hz, PCH2N), 4.52 (AB system, 6H, NCH2N). 13C{1H} NMR (CD3CN): δ 146.1 (s, C(O)CCHCH), 132.2 (s, NCHCH), 130.4 (s, C(O)CCH), 71.2 (d, JPC 9 Hz, NCH2N), 54.5 (d, JPC 37 Hz, PCH2N) (unable to identify remaining carbons due to poor signal to noise ratio because of the low solubility and stability of compound). IR (cm−1): ν 1654 (C=O), 1292 (P=N), 1089 (ClO4), 254 and 302 (M-Cl). Conductivity: Λ = 97.8 µS/cm.

[PdCl2(N,N-IM)] (3)

[PdCl2(COD)] (0.041 g, 0.15 mmol) and 1 (0.042 g, 0.15 mmol) were dissolved in dry and degassed CH2Cl2 (4 mL) and left to react for 3 hours at room temperature after which an orange precipitate formed. The solvent was then reduced to a minimum in vacuo and upon addition of Et2O a pale orange solid was obtained which was washed twice with CHCl3 and dried in vacuo. Yield: 0.035 g (52%). Anal. Calcd for C12H16Cl2N5OPPd (454.59): C, 31.71; H, 3.55; N, 15.41. Found: C, 31.63; H, 3.23; N, 15.41. MS (MALDI+) [m/z]: 420.0 [M-Cl]. 31P{1H} NMR(DMSO-d6): δ −6.4 (s). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 9.03 (1H, d, 3JHH 5 Hz, NCH), 8.20 (1H, t, 3JHH 7 Hz, C(O)CCHCH), 7.85 (1H, d, 3JHH 8 Hz, C(O)CCH), 7.78 (1H, t, 3JHH 7 Hz, NCHCH), 4.39 (AB system, 6H, NCH2N), 4.42 (6H, 2JPH 8 Hz, PCH2N). 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 173.8 (s, C=O), 150.5 (s, C(O)C(N)(CH)), 149.1 (s, NCH), 141.4 (s, C(O)CCHCH), 129.6 (s, NCHCH), 127.1 (s, C(O)CCH), 71.4 (d, JPC 9 Hz, NCH2N), 53.7 (d, JPC 37 Hz, PCH2N). IR (cm−1): ν 1659 (C=O), 1290 (P=N), 290 (M-Cl).

[PtCl2(N,N-IM)] (4)

PtCl2 (0.080 g, 0.30 mmol) and 1 (0.083 g, 0.30 mmol) were refluxed for 2 days in a mixture of CH2Cl2 (10 mL) and acetone (2 mL). The reaction mixture was filtered though Celite to remove any unreacted PtCl2, giving a yellow solution. The solvent was reduced to a minimum in vacuo and upon addition of Et2O a yellow solid was obtained, which was washed twice with CHCl3 and dried in vacuo. Yield: 0.025 g (15%). Anal. Calcd for C12H16Cl2N5OPPt (542.01): C, 26.53; H, 2.97; N, 12.89. Found: C, 25.90; H, 2.48; N, 13.16. MS (MALDI+) [m/z]: 502.1 [M-Cl]. 31P{1H} NMR(DMSO-d6): δ −4.4 (s). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 9.35 (1H, d, 3JHH 5 Hz, NCH), 8.33 (1H, t, 3JHH 8 Hz, C(O)CCHCH), 7.83 (2H, d, 3JHH 8 Hz, C(O)CCH + NCHCH), 4.95 (6H, d, 2JPH 8 Hz, PCH2N), 4.42 (6H, s, NCH2N). 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 173.8 (s, C=O), 151.1 (s, C(O)C(N)(CH)), 150.0 (s, NCH), 141.9 (s, C(O)CCHCH), 130.6 (s, NCHCH), 128.0 (s, C(O)CCH), 71.3 (d, JPC 7 Hz, NCH2N), 55.1 (d, JPC 50 Hz, PCH2N). IR (cm−1): ν 1667 (C=O), 1282 (P=N), 290 (M-Cl).

2.3. X-Ray crystallography

Single crystals of 3 and 4 (see details below) were mounted on a glass fiber in a random orientation. Data collection was performed at room temperature on a Kappa CCD diffractometer using graphite monochromated Mo-Kα radiation (λ=0.71073 Å). Space group assignments were based on systematic absences, E statistics and successful refinement of the structures. The structures were solved by direct methods with the aid of successive difference Fourier maps and were refined using the SHELXTL 6.1 software package. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Hydrogen atoms were assigned to ideal positions and refined using a riding model. Details of the crystallographic data are given in Table S1 (Supplementary Information (SI)). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. (CCDC 858692 for compound 3, and 858693 for compound 4).

3: Crystals of 3 (orange prisms with approximate dimensions 0.28 × 0.24 × 0.24 mm) were obtained from a solution of 3 in DMSO by slow diffusion of Et2O at RT. 4: Crystals of 4 (yellow prisms with approximate dimensions 0.26 × 0.24 × 0.20 mm) were obtained from a solution of 4 in DMSO by slow diffusion of Et2O at RT.

2.4. Computational Methods

All calculations reported here were carried out using the Gaussian 09 program package. [26] All gas phase structures were optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of density functional theory (DFT) in combination with relativistic effective-core potential cc-pVDZ-PP for heavy metals (platinum and gold) where appropriate. Aqueous solution structures are found with PCM (polarizable continuum model) full geometry optimization at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of DFT in combination with relativistic effective-core potential ccpVTZ- PP for heavy metals (platinum and gold) where appropriate. Computed frequencies were positive, in all cases, indicating that the optimized structures represent the minima of ground-state potential-energy surfaces. In addition, a simple visual comparison of computed IR spectra with experimental spectra was performed to further validate reliability of computed structures.

2.5. Determination of Compound Cytotoxicity

The human T-cell leukemia Jurkat (clone E6.1) from the ATCC collection and the prostate carcinoma DU-145 were routinely cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% FCS (fetal calf serum), L-glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin (hereafter, complete medium). Blood samples from healthy donors were obtained from the Banco de Sangre y Tejidos de Aragón. All subjects gave written informed consent and the Ethical Committee of Aragón approved the study. Normal T-lymphocytes (peripheral blood mononuclear cells: PBMC) were freshly isolated by Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation. After isolation, normal PBMC were kept in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% decomplemented FCS, L-glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin. Jurkat cells lacking Bak were generated using RNA interference techniques, as described previously [27]. For toxicity assays, Jurkat cells (5 ×105 cells/mL), DU145 cells (1 ×105 cells/mL) or normal T-lymphocytes PBMC (3 × 106 cells/mL) were seeded in flat-bottom 96-well plates (100 µl/well) in complete medium. DU145 cells were allowed to attach prior to addition of cisplatin or tested compounds. Compounds were added at different concentrations in triplicate. Cells were incubated with cisplatin or compounds for 24 h and then cell proliferation was determined by a modification of the MTT-reduction method [28]. Total cell number and cell viability were determined by the Trypan-blue exclusion test. Apoptosis/necrosis hallmarks were analyzed by simultaneously measuring the mitochondrial membrane potential, exposure of phosphatydilserine and 7-AAD uptake. In brief, 2.5×105 cells in 200 µl were incubated in ABB (140mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.4), with either 5nM DiOC6(3) or 60nM TMRE (both from Molecular Probes) at 37°C for 10 minutes. AnnexinV-PE or AnnexinV-FITC (Invitrogen) at a concentration of 0.5 µg/ml or 7-AAD (50ng/µl) was added to samples and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 15 minutes. In all cases, cells from each well were diluted to 1 ml with ABB to be counted by flow cytometry (FACScan, BD Bioscience, Spain).

2.6. Interaction of metal complexes with CT DNA by Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Stock solutions (5 mM) of each complex were freshly prepared in DMSO-H2O (1:99) prior to use. Aliquots were added to a solution of CT (Calf Thymus) DNA (195 µM) also freshly prepared in buffer (5 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaClO4, pH = 7.39) to achieve molar ratios of 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 drug/DNA while keeping a total volume of 3 mL. The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 20 h in the dark. All CD spectra of DNA and of the DNA-drug adducts were recorded at 25 °C over a range 220–320 nm and finally corrected with a blank and noise reduction. Noise reduction was performed using the Savitzky-Golay smoothing filter incorporated in the Chirascan software. The spectra are given in molar ellipticity (millidegrees).

2.7. Interaction of metal complexes with plasmid (pBR322) DNA by Electrophoresis (Mobility Shift Assay)

10 µL aliquots of pBR322 plasmid DNA (20 µg/mL) in buffer (5 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaClO4, pH = 7.39) were incubated with molar ratios between 0.25 and 4.0 of the compounds at 37 °C for 20 h in the dark. Samples of free DNA and cisplatin-DNA adduct were prepared as controls. After the incubation period, 2 µL of loading dye were added to the samples and of these mixtures, 7 µL were finally loaded onto the 1 % agarose gel. The samples were separated by electrophoresis for 1.5 h at 80 V in Tris-acetate/EDTA buffer (TAE). Afterwards, the gel was stained for 30 min with a solution of GelRed Nucleic Acid stain.

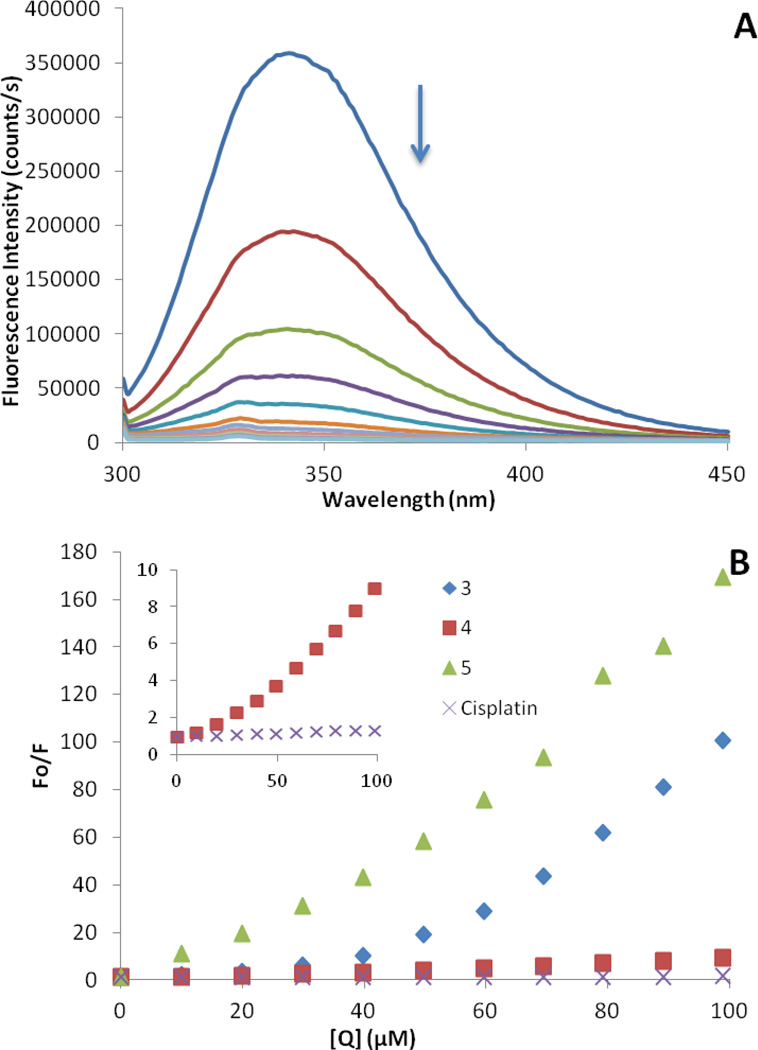

2.8. Interaction of metal complexes with HSA by Fluorescence Spectroscopy

The excitation wavelength was set to 295 nm, and the emission spectra were recorded at room temperature in the range of 300 to 450 nm. The fluorescence intensities of the metal compounds, the buffer and the DMSO are negligible under these conditions, and so is the effect of additions of pure DMSO on the fluorescence of HSA. An 8 mM solution of each compound in DMSO was prepared and ten aliquots of 2.5 µL were added successively to a solution of HSA (10 µM) in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.39), the fluorescence being measured 240 s after each addition. The data was analyzed using the classical Stern-Volmer equation F0/F = 1 + KSV[Q].

2.9. Interaction of metal complexes 3 and 4 with HSA by Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

The HSA and titrant solutions were prepared in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.39) and degassed prior to titration. In a standard experiment, the protein (5µM) was titrated with the metal complex solution (1.5–3 mM) by a series of 34 successive injections of 7 µL each, with an interval of 240 s between injections. A background titration of titrant solution into buffer was substracted from each experimental titration to account for heat of dilution. The data was analyzed with a two-site binding model using Origin 50 software supplied with the microcalorimeterl. Equilibrium was reached after each addition of ligand to protein during the ITC titrations as evidenced by the return to baseline of the trace of microcalories heat released per unit time in the raw data collected for the binding experiments. Concentrations are not directly measured but calculated based upon the starting total protein concentration and the actual titration curve generated from the integrated heat released for each injection of ligand solution of known concentration into the known volume of protein solution in the ITC cell.

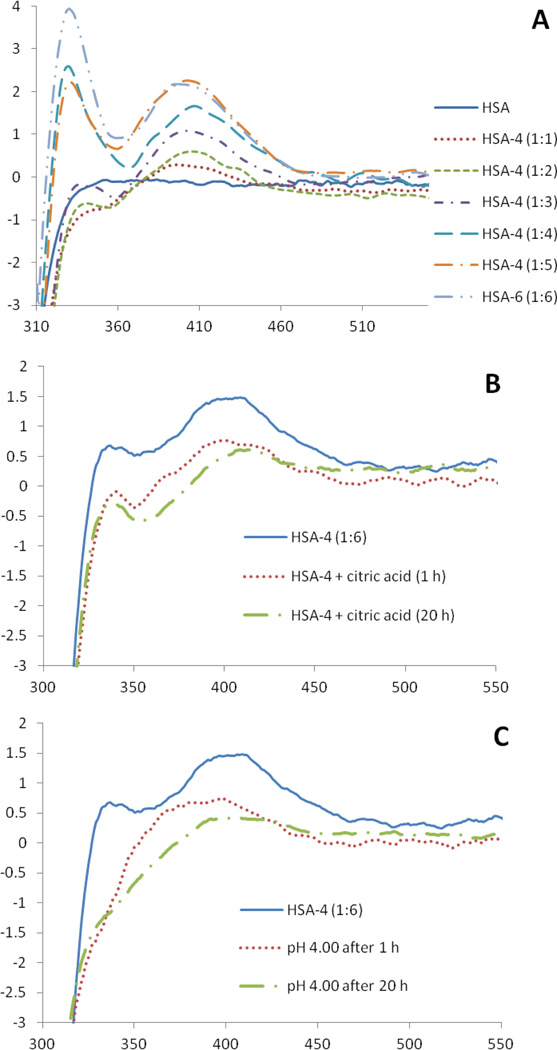

2.10. Reversibility of binding to HSA by Circular Dichroism

The interaction of complexes 3 and 4 with HSA was studied by CD spectroscopy in the visible region (300–550 nm) in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.39). 2 mL samples of 1.12 × 10−4 M HSA were incubated at 37 °C for 20 h with increasing amounts of compound 3–4 (1–7 eq); the interaction was monitored by the appearance of a band in the visible region at 360 nm for 3 and 395 nm for 4. All spectra were corrected by subtraction of a blank consisting of a solution of drug in buffer at the appropriate concentration for each sample. For binding reversibility studies, to a 2 mL sample of saturated HSA-3 or HSA-4 incubated previously for 20 h at 37 °C, was added either 20 µL of concentrated HCl to reach pH 4.00 or the appropriate amount of a 60 mM solution of citric acid in the same buffer to reach a 1:3 complex:chelator ratio. The CD spectra were recorded in the visible region after 1 and 20 hours.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis, characterization and stability of the new compounds

The ligand 1 and metallic compounds (2–3) can be obtained in moderate to high yields following the procedure depicted in Scheme 1. All the new compounds (1–4) were fully characterized (see Experimental) and are air-stable red (2), orange (3) and yellow (4) solids. The structure of cationic Au compound 2 was confirmed by IR (bands that can be assigned to anionic ClO4−), conductivity measurements (1:1 electrolyte) and high resolution mass spectrometry. The stabilities of the ligand and the complexes were evaluated by 31P{1H} and 1H NMR spectroscopy in deuterated solvents and mixtures of deuterated solvents. Ligand 1 is soluble in H2O, and solvents such as DMSO and CHCl3. It is stable in DMSO solution at RT for 14 days whereas in H2O it is stable for 3 h.

The cationic Au derivative 2 is soluble in CH3CN and DMSO and insoluble in chlorinated solvents, Et2O, most non-polar organic solvents and H2O. At room temperature it is stable in CH3CN solution for 24 h while it decomposes in DMSO solution after 4 h. In a mixture 50:50 DMSO:H2O compound 2 decomposes after 30 min to phosphine oxide TPA=O and to compound 5 (equation 1). Compound 5 (containing deprotonated uninegative bidentate ligand picolinamide) had been previously reported as a cytotoxic agent against MOLT-4 (human leukemia) and C2C12 (mouse myoblast cancer) cell lines [25]. Neutral complexes 3 and 4 are soluble in DMSO in which they are stable for over 7 days and they are also stable in mixtures 50:50 DMSO:H2O for over 4 days. Compounds 2, 3 and 4 are soluble at micromolar concentration in mixtures 1:99 DMSO:H2O or DMSO:buffer.

Equation 1.

Decomposition products of compound 2 in DMSO solution or a 50:50 mixture of DMSO:H2O at RT after 4 hours or 30 min respectively.

The crystal structures of 3 and 4 (Structure of 3 in Fig. 2) were compared to the molecular structures obtained by means of density functional calculations (see Experimental and Supplementary Material). Selected bond lengths and angles are collected in Table 1 and in Table S2. The geometry about the Pd(II) and Pt(II) centers is pseudo-square planar with the N(2)-M(1)-N(1) angle of 80.86(8)° (Pd 3) and 80.4(3)° (Pt 4) suggesting a rigid ‘bite’ angle of the chelating ligand. The Pd and Pt centers are on an almost ideal plane with negligible deviations from the least-squares plane. The coordination plane for Pd and Pt and the metallocyclic plane are only slightly twisted to give an angle of 2.6° (3) and 2.4° (4) between them. The main distances M-N(1) or M-N(iminic) and M-N(2) found for 3 and 4 are very similar to those found in related iminophosphorane complexes like [Pd{k2-C,N-C6H4(PPh2=NC6H4Me-4’)-2}{μ-OAc)}]2, [Pd{k2-C,N-C6H4(PPh2=NC6H4Me-4’)-2}(tmeda)]ClO4 [29],[Pd(C6H4CH2NMe2)(Ph3PNC(O)-2-NC5H4)]ClO4 [30] and [PtCl(PMe2Ph){(N(p-Tol)=PPh2)2CHCH3}]Cl [31]. We were unable to get crystals from the Au(III) compound 2 useful for a single crystal X-ray diffraction study but we got good estimates for its structural parameters from density functional calculations (see Table 1 and Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Molecular structure of the compound [PdCl2(N,N-IM) ] 3 with the atomic numbering scheme. The structure for compound [PtCl2(N,N-IM) ] 4 is identical and selected bond and angles for 3 and 4 are collected in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected structural Parameters of complexes 2–4 obtained from DFT calculations and the comparison with experimental values.a Bond lengths in Å and angles in °. (Full table S2 in supplementary material)

| 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcd | Exp | Calcd | Exp | Calcd | |

| M-N(1) | 2.097 2.073b |

2.052(2) | 2.112 2.083b |

2.058(6) | 2.098 2.076b |

| M-N(2) | 2.086 2.064b |

2.024(2) | 2.069 2.049b |

2.004(7) | 2.040 2.031b |

| M-Cl(1) | 2.304 2.321b |

2.2943(8) | 2.311 2.349b |

2.300(2) | 2.326 2.358b |

| M-Cl(2) | 2.301 2.309b |

2.2922(8) | 2.329 2.342b |

2.299(2) | 2.339 2.354b |

| P-N(1) | 1.700 1.694b |

1.658(2) | 1.663 1.678b |

1.661(7) | 1.667 1.681b |

| N(1)-C(1) | 1.392 1.390b |

1.373(3) | 1.377 1.378b |

1.366(11) | 1.379 1.379b |

| N(1)-M-N(2) | 80.62 80.84b |

80.86(8) | 79.54 80.59b |

80.4(3) | 79.64 80.39b |

| Cl(1)-M-Cl(2) | 88.88 88.30b |

88.74(3) | 90.52 88.86b |

88.17(9) | 89.46 87.92b |

Gaussian 09 program package (see Experimental), calculated in gas phase.

Calculated in PCM aqueous solution (see Experimental).

The molecular structure of the cation in the Au(III) compound 2 is depicted in Fig. 3. Like in the Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes 3 and 4, the metal center is in a pseudo-square planar arrangement (N(2)-Au(1)-N(1) angle of 80.62°). The distances calculated for Au-N(1) (Au-N(iminic)) and Au-N(2) (Au-N(pyridine) and Au-Cl are in the range of those found for related complexes like [Au(Ph2PyP=NC(O)Ph)Cl2]ClO4 [18] and those obtained for previously described compound 5 [AuCl2(HN-C(O)-2-NC5H4)] [25]. The longer distances P-N(1) of 1.700 Å and N(1)-C(1) of 1.392 Å in 2 (compared to those in 3 and 4) are indicative of a greater delocalized charge density [30] than in neutral Pd and Pt compounds (3 and 4). This may be the cause for the lower stability of compound 2 in water or in polar solvents compared to complexes 3 and 4.

Fig. 3.

Optimized structure of the cation in [AuCl2(N,N-IM)]ClO4 (2) obtained from DFT calculations.

Frequencies of selected normal vibrational modes were also determined by DFT methods (Table S2) for the optimized structures of compounds 2–4. The calculated and the experimental frequencies of M-Cl and P=N and C=O stretching modes are in reasonable agreement [32].

3.2. Cytotoxicity Studies

Cytotoxicity results for ligand 1 and the new metallic compounds (2–4) are collected in Table 2. Values for the decomposition products of ligand 1 and compound 2 (the phosphine oxide TPA=O and gold compound 5, Equation 1) are also collected for comparison purposes. The cytotoxicity (by a modification of the MTT-reduction method, see Experimental) was evaluated against two selected cell lines: human Jurkat-T acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells and DU-145 human prostate cancer cells. Cells were incubated in the presence of the compounds for 24 h. The sensitivity of T-cell leukemia Jurkat cells to compounds cisplatin, 1–5, and T-PA=O was compared to that of normal T-lymphocytes (PBMC). Compound 3 (Pd) was less cytotoxic than cisplatin for Jurkat cells but Pt (4) and Au compounds 2 and 5 were two (4), seven (5) or even eleven (2) times more cytotoxic than cisplatin (Table 2). The IC50 values displayed by the gold compounds are similar to that reported for an organogold(III) iminophosphorane complex described by us (b in Figure 1 [16]) to Jurkat leukemia cells (0.2 µM) and CLL (B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells) derived from patients; 60 nM to 100 nM) [15]. Compound 5 was reported to have an IC50 value of 3.1 µM for MOLT-4 human leukemia cell line [25]. All compounds were less toxic to PMBC than to T-Jurkat cell lines. The compounds were twelve (2), ten (3) or seven times (4, 5) less toxic to the normal lymphocytes than to the leukemia cell line. However we have found here that cisplatin is 70 times less toxic to PMBC than to Jurkat cell lines.

Table 2.

IC50 (µM) of cisplatin, ligand 1, phosphine oxide TPA=O and metal complexes 2–5 complexes in human cell lines. All compounds were dissolved in 1% of DMSO and diluted with water before addition to cell culture medium for a 24 h incubation period. Cisplatin was dissolved in water.

| Jurkat | PBMC | DU-145 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin | 7.4±2.1 | 500±18 | 79.2±15.8 |

| TPA=O | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 1 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 2 | 0.66±0.07 | 7.9±2.9 | 17.4±5.1 |

| 3 | 19.6±2.6 | 213±22 | 301±27 |

| 4 | 3.5±0.7 | 23.4±0.9 | 65.3±7.0 |

| 5 | 0.97±0.4 | 7.3±3.3 | 19.9±1.7 |

The cytotoxicity to the DU-145 human prostate cancer cell line was evaluated and while Pd (3) was less cytotoxic than cisplatin for this cell line, the Pt (4) compound (65.3 µM) had an IC50 value similar to that of cisplatin (79.2 µM). Au compounds 2 and 5 were more cytotoxic (17.4 µM (2) and 19.9 µM (5), 4.5 and 4 times more cytotoxic than cisplatin). The value obtained for compounds 2 and 5 is in line with values obtained with heterometallic Ti-Au2 complexes recently described by our lab (14–27 µM) with a live imaging method after 24 h [33].

In addition, the cytotoxicity of ligand 1 and its decomposition product phosphine oxide TPA=O is notably low in all cell lines studied having IC50 values greater than 500 µM. This indicates that the cytotoxic effect is due to the metal complex and that the cytotoxicity on the cancer cell lines follows the order Au>Pt>Pd for the metal center. Compound 2 decomposes quickly in solution to compound 5 and therefore the IC50 values obtained for both derivatives are very similar.

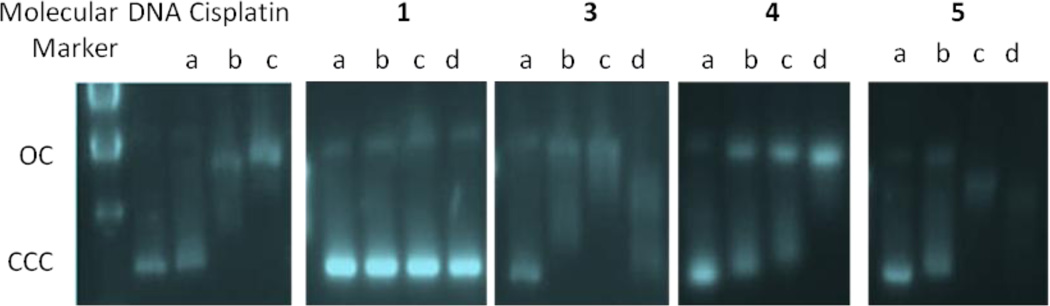

Preliminary results on the cell death pathway caused by complexes 2–5 showed an inhibition of cell growth in the period studied (24 h) in DU-145 human prostate cancer cells. The morphology of the cells is very similar to that of the controls (Fig. 4, selected examples Au (5) and Pt (4) compounds), with neither signs of nuclear condensation nor chromatin fragmentation. Also, DU-145 showed not phosphatydilserine exposure or membrane permeabilization (Fig. 5), confirming that compounds 4 and 5 do not induce cell death in DU-145 at 24 h. In contrast, analysis of nuclear morphology revealed that compounds 4 and 5 induced cell death in Jurkat cells. Both apoptotic, condensed and fragmented nuclei, and necrotic, swollen nuclei were observed (Fig. 4). Flow cytometry after AnnexinV-APC/7-AAD staining (Fig. 5) confirmed that a significant percentage of cells were necrotic (7-AAD+ cells, upper right quadrant). Thus the mode of action of the gold compound [AuCl2(HN-C(O)-2-NC5H4)] 5 and new hydrophilic iminophosphorane platinum complex 4 in Jurkat cells seems different from that of cisplatin (which is via apoptosis) [34]. It is estimated that about 1% of intracellular cisplatin binds to DNA primarily by forming intrastrand cross-links between adjacent purines [3, 35] and triggers the DNA-damage response that activates canonical apoptotic pathways [36].

Fig. 4.

Compounds 3–5 induce apoptosis and necroptosis. Jurkat and DU-145 cells were cultured for 24 h in the presence of compounds 3–5 or left untreated. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 333248 (10 µg/ml) and cells were photographed under UV light. The figure shows the images of controls and selected compounds 4 and 5.

Fig. 5.

Jurkat cells (5 ×105 cells/ml) or DU145 cells (1 ×105 cells/ml) were treated for 24 h with compounds 4 or 5 (concentrations for IC50 values). Apoptosis/necrosis hallmarks were analyzed by simultaneously measuring the exposure of phosphatidylserine and 7-Amino-Actinomycin D (7-AAD) uptake as described in the Experimental section. The percentage of cells in each region is indicated.

We found that iminophosphorane gold(III) complexes a and b (Fig. 1) induced both necrosis and apoptosis and that the necrotic cell death induced by a and b was Bax/Bak- and caspase-independent [15]. We demonstrated that compounds a and b act mainly through ROS generation that leads to necrosis [15]. Similarly, compounds 4 and 5 seem to induce both necrotic and apoptotic cell death in Jurkat leukemia cells. Necrotic cell death that we observed in a fraction of cells could correspond to necroptosis, a “programmed” necrosis, since it has been demonstrated by others that ROS accumulation can be implicated in this type of cell death [37].

The activity of compounds 3–5 and cisplatin against apoptosis-resistant cells was also tested (Fig. S1). Multidomain proapoptotic proteins Bax and Bak are essential for the onset of mitochondrial permeabilization and apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway. Interestingly, we observed that compounds 4 and 5 exhibited some toxicity to Jurkat sh-Bak cells (Bax/Bak-deficient Jurkat cells) similar to previous results with (compounds a and b in Fig. 1) [15]. This could be an advantage over cisplatin, whose activity is totally dependent on the presence of functional Bax and Bak.

3.3. Interaction with DNA

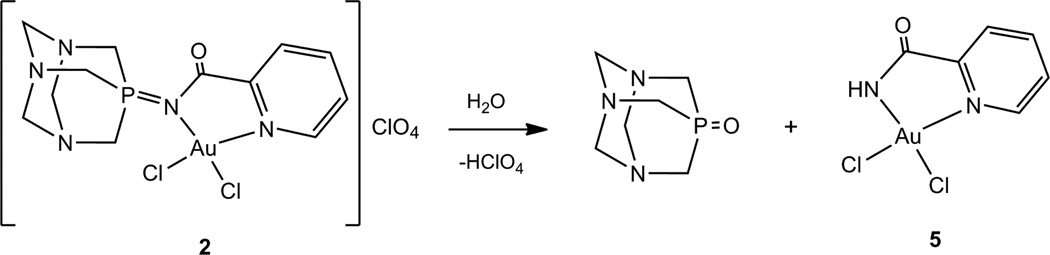

Since DNA replication is a key event for cell division, it is among critically important targets in cancer chemotherapy. Most cytotoxic platinum drugs form strong covalent bonds with the DNA bases [38, 39]. However, a variety of platinum compounds act as DNA intercalators upon coordination to the appropriate ancillary ligands [40]. There are also reports on palladium derivatives interacting with DNA in covalent [41, 42] and noncovalent ways [43–45]. While most gold(III) and gold(I) compounds display reduced affinity for DNA [9, 15, 16], gold(I)-phosphine derivatives with weakly bound ligands (such as halides) bind in a nondenaturing fashion to DNA [35, 46]. DNA conformational alterations can be detected by means of circular dichroism spectroscopy [37]. When Calf Thymus DNA is incubated with increasing amounts of Au derivative (5), a slight decrease (Fig. 6) of the intensities of the negative and especially the positive bands are observed, indicating a decrease in helicity (destabilizing effect) [47]. Those changes in the stacking and the helicity of CT DNA at low drug:nucleotide ratios (r = 0.1/0.5) are probably related to electrostatic effects or to the ability of the compounds to intercalate DNA. Similar CD spectra were observed with other cationic square-planar gold(III) compounds with N- containing ligands such as [Au(phen)Cl2]Cl or [AuCl(terpy)]Cl2 [48]. Au(III) complexes structurally related to compound 5 derived from aminoquinoline such as [Au(Quinpy)Cl]Cl, [Au(Quingly)Cl]Cl and [Au(Quinala)Cl]Cl were proposed to interact by intercalation, although no CD spectra were provided [49].

Fig. 6.

CD spectra of CT incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with Au derivative (5) at 0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5 and 1 ratios.

In contrast, when CT DNA is incubated for 20h with increasing amounts of Pd (3), and particularly Pt (4) there are not noticeable changes at low DNA-drug ratios (up to r = 0.5 or even 1 for 4) and only at ratios of 1 is there a small increase of the positive band indicating a small stabilizing effect most plausibly by electrostatic effects (Fig. S2).

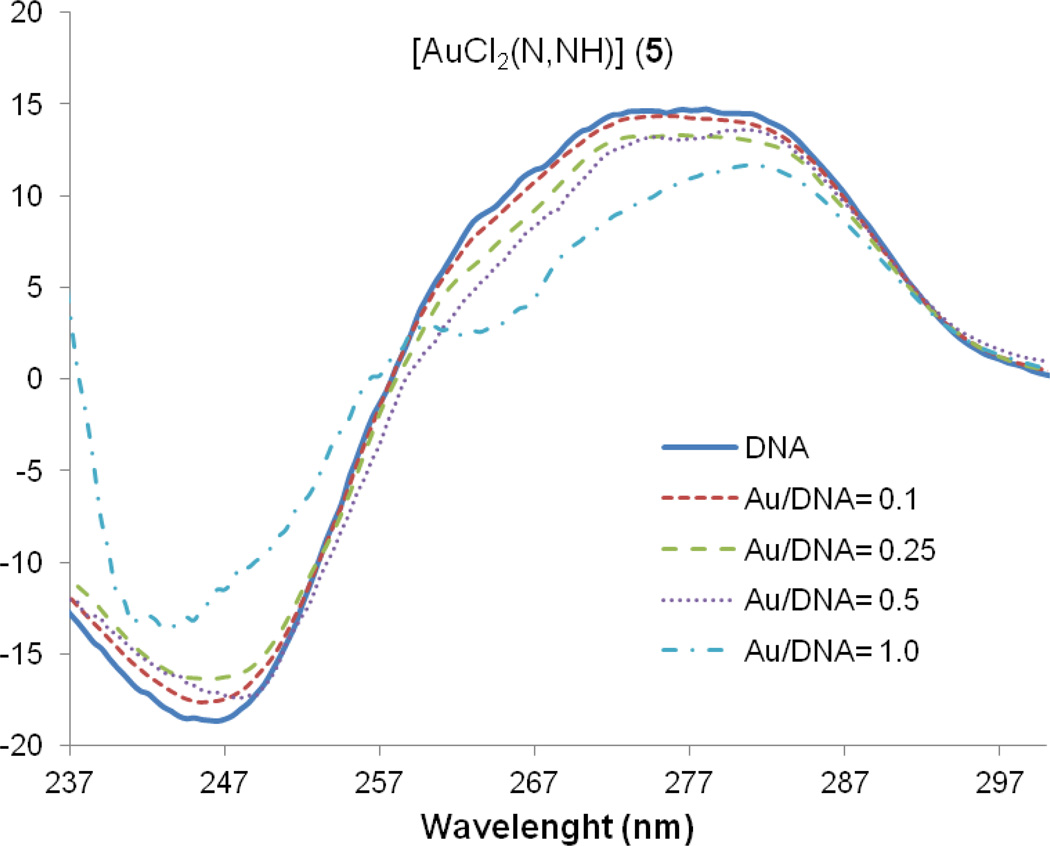

We also performed agarose gel electrophoresis studies on the effects of compounds 3–5 on plasmid (pBR322) DNA (Fig. 7). This plasmid has two main forms: OC (open circular or relaxed form, Form II) and CCC (covalently closed or supercoiled form, Form I).

Fig. 7.

Electrophoresis mobility shift assays for cisplatin and compounds 1, 3–5 (see Experimental for details). DNA refers to untreated plasmid pBR322. a, b, c and d correspond to metal/DNA ratios of 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 respectively.

Changes in electrophoretic mobility of both forms are usually taken as evidence of metal-DNA binding. Generally, the larger the retardation of supercoiled DNA (CCC, Form I), the greater the DNA unwinding produced by the drug [50]. Binding of cisplatin to plasmid DNA, for instance results in a decrease in mobility of the CCC form and an increase in mobility of the OC form (see lanes a, b and c for cisplatin in Fig. 7) [51]. Treatment with increasing amounts of ligand 1 does not cause any shift for either form, consistent with no unwinding or other change in topology under the chosen conditions. Treatment with increasing amounts of compounds 3–5 retards the mobility of the faster-running supercoiled form (Form I) especially at high molar ratios. Similar patterns of mobility have been described for some Pt(IV) complexes in the presence of glutathione as reducing agent [51]. In these cases, although the resulting Pt(II) products bind to closed circular DNA, their effect in the mobility of Form I (or CCC) DNA is different from that produced by cisplatin [51]. These results are in agreement with the small stabilizing effects observed in the interaction of the Pd (3) and Pt (4) compounds with calf thymus DNA by CD spectroscopy. These effects are different from those observed in the CD spectra of cisplatin and other Pd and Pt derivatives which bind in covalent cis-bidentate fashion to DNA [33].

In conclusion, the experiments probing DNA-drug interactions showed that new Pd (3) and Pt (4) IM complexes do not interact strongly with Calf Thymus DNA at physiological pH in vitro and that gold compound (5) interacts more strongly with DNA most likely by intercalation. All the complexes interact with plasmid (pBR322) DNA, most plausibly in a way different from that of cisplatin.

3.4. Interaction with HSA

Human serum albumin is the most abundant carrier protein in plasma and is able to bind a variety of substrates including metal cations, hormones and most therapeutic drugs. It has been demonstrated that the distribution, the free concentration and the metabolism of various drugs can be significantly altered as a result of their binding to the protein [52]. HSA possesses three fluorophores, these being tryptophan (Trp), tyrosine (Tyr) and phenylalanine (Phe) residues, with Trp214 being the major contributor to the intrinsic fluorescence of HSA. This Trp fluorescence is sensitive to the environment and binding of substrates or changes in conformation that can result in quenching. Quenching can occur by two different mechanisms, a dynamic mechanism caused by diffusional collisions between the protein and the quencher, and a static mechanism resulting from the formation of a non fluorescent complex. The fluorescence spectra of HSA in the presence of increasing amounts of 3–5 and cisplatin were recorded in the range of 300–450 nm upon excitation of the tryptophan residue at 295 nm. The compounds caused a concentration dependent quenching of fluorescence without changing the emission maximum or shape of the peaks, as seen in Fig. 8 for compound 3. The fluorescence data was analyzed by the Stern-Volmer equation. While a linear Stern-Volmer plot is indicative of a single quenching mechanism, either dynamic or static, the positive deviation observed in the plots of F0/F versus [Q] of our compounds (Fig. 8) is indicative of the presence of different binding sites in the protein. These binding sites may have naturally different affinities for the quencher, or the effects may be due to changes in the conformation of the protein after initial interactions that expose new binding sites previously inaccessible to the quencher [53]. In this graph higher quenching by the iminophosphorane complexes and 5 was observed compared to that of cisplatin under the chosen conditions. This is probably an indication of the faster hydrolysis in aqueous solution of our compounds compared to that of cisplatin. The interaction of cisplatin and related compounds with HSA have been studied by a variety of analytical techniques [52] and despite varying the techniques and conditions (such as incubation time, initial concentration of protein, drug:protein ratio and the nature of incubation medium) there seems to be a common strong and irreversible binding of cisplatin to HSA most plausibly to methionine and histidine residues [54].

Fig. 8.

(a) Fluorescence titration curve of HSA with compound 3. Arrow indicates the increase of quencher concentration. (b) Stern-Volmer plot for quenching with compounds 3–5 and cisplatin.

In an attempt to gather more information about the nature of the interaction between the iminophosphorane complexes and HSA, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were carried out. This sensitive tool allows for a complete characterization of the thermodynamics of drug binding. ITC has been used for the study of the interaction of Ni2+ [55], Co2+ [56], Er3+ [57] and Ru2+-chloroquine [58] compounds with HSA but to our knowledge, the binding of palladium or platinum compounds has not been assessed with this technique. The data obtained from the titrations (illustrated in Fig. 9 for complex 3) were best fitted to a model of two sequential binding sites with different affinities for the drug. A sequential binding model was required to fit the data based upon the very large errors in fits using a single site, and the excellent fit to data using 2 sites. The errors are obtained from the iterated fitting routines provided in the software for the ITC apparatus such that the quality of fits can be evaluated both visually and from parameters like errors in KD and n, and X-squared values (see experimental section). The thermodynamic parameters for the interaction of compounds 3 and 4 with the protein are collected in Table 3 with K1 of (5.29 ± 0.87)×104 (3) and (1.43 ± 0.13)×104 (4). The first binding site has a binding affinity approximately 40 times larger than the second one for both Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes ([1.41 ± 0.04]×103 3 and [371.6 ± 20.05] 4), hence the sequential interaction. Binding constant values for other metal ions (Ni2+ [55], Co2+ [56], Er3+ [57]) or metal complexes (Ru2+ [58]) binding to HSA are also in the mM to microM range.

Fig. 9.

ITC titration of HSA with complex 3. Data was corrected for heat of dilution (see experimental).

Table 3.

Thermodynamic parameters obtained from ITC experiments for compounds 3 and 4.

| 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| K1 (M−1) | (5.29 ± 0.87)×104 | (1.43 ± 0.13)×104 |

| ΔH1 (Kcal/mol) | (−1.06 ± 0.16)×104 | (−4.69 ± 0.41)×104 |

| ΔS1 | −14.00 | −138.2 |

| K2 (M−1) | (1.41 ± 0.04)×103 | 371.6 ± 20.05 |

| ΔH2 (Kcal/mol) | (−3.96 ± 0.08)×105 | (−1.89 ± 0.10)×106 |

| ΔS2 | −1313 | −6321 |

The ITC results may explain the lack of linearity observed in the fluorescence quenching studies, as the Stern-Volmer method assumes all binding sites to be equivalent. Unfortunately, ITC experiments with the gold(III) compound 5 could not be performed due to poor solubility at the required concentrations. Similarly, experiments with cisplatin did not yield useful data. The slow hydrolysis of the chloride ligands requires incubation of the drug with the protein for several hours or days [52], which is incompatible with the ITC technique.

Attempts to correlate the Ka of a drug with the percentage plasma protein binding have been carried out [59, 60]. The first binding constant for the Pt compound (4) (1.43 ± 0.13)×104 is correlated with a roughly 90% plasma protein binding which is considered the upper limit for effective chemotherapeutics (values higher than 90% are considered to be disadvantageous). More important however, is to asses if this binding can be reversed. If the interaction to HSA is too strong, the drug might not be able to reach the cellular target. Reversibility can be achieved by contact with a low pH environment, as in tumor tissues, or by chelators present in the cytosol that may displace the amino acids in typical HSA-metallodrug complexes. We studied the reversibility of the binding of HSA to compounds 3 and 4 by CD spectroscopy. The protein was first titrated with compounds 3 and 4, achieving saturation with 4 and 6 equivalents respectively as determined by the appearance and increase in intensity of a visible band at 360 nm for 3 (negative) and 395 nm for 4 (positive) in their CD spectra (Fig. 10a and S3a).

Fig. 10.

a) CD spectra (visible region) of HSA with 4. b) Effect of the addition of 15 equivalents of citric acid on the spectrum of the HSA-4 complex over time. c) Effect of low pH on the spectrum of the HSA-4 complex over time.

By using a metal ion chelator like citric acid, a decrease of the intensity of the visible bands was observed, especially in the case of platinum compound 4, with a 50% reduction after only 1 hour of incubation with a 3-fold excess of the chelating agent (Fig. 11b). The effect of citric acid on the HSA-3 adduct was less significant with only a 12% decrease after the same period of time (Fig. S3b). Decreases of 25–30% in the same conditions were achieved with arene-Ru(II)-chloroquine antimalarial and antitumor agents whose binding to HSA was considered reversible [58]. In a different experiment with our new complexes, the pH of the buffered solutions was decreased from 7.40 to 4.00 by addition of HCl. An effect on the spectrum of the HSA-4 adduct was observed again, by the decrease of the visible band intensity of 52% after 1 hour (Fig. 11c), while the CD spectrum of the HSA-3 adduct showed large shifts and shape modifications of the visible band but no genuine indication of the Pd center being released from the protein (Fig. S3c). A decrease of 18%–40% after 96 h incubation was achieved with the previously described arene-Ru(II)-chloroquine derivatives whose binding to HSA was reversed by a decrease of pH [58]. Thus, we propose that the reversibility of the binding 4 to HSA by chelators present in the cytosol and/or contact with a low pH environment is possible. However, for the Pd (3) complex, some permanent bands were seen after long incubation in the presence of citrate (Fig. S3b) or at low pH (Fig. S3c) that could reflect modification of HSA by this metal. Therefore, no evidence for release (reversibility) was seen using CD spectroscopy for the Pd (3) derivative.

4. Conclusion

We have prepared new hydrophilic iminophosphorane complexes of d8 metals. While we did not get stable gold(III) complexes containing the water-soluble ligand reported here, Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes were stable in the used conditions for biological experiments. The cytotoxicity, cell death pathway and reactions with DNA and HSA of the gold(III) compound were due to the generation of a cytotoxic decomposition product [AuCl2(HN-C( O)-2-NC5H4)] 5, previously reported. The Pd compound (3) was found to be less cytotoxic than cisplatin and to have a related mode of action. We found that the Pt(II)-iminophosphorane coordination derivative (4) was more cytotoxic than cisplatin to leukemia cell lines (both T-Jurkat and cisplatin-resistant Jurkat sh-Bak). 4 showed higher toxicity against leukemia cells when compared to normal human T-lymphocytes or PBMC and its cell death pathway seems to be different from that of cisplatin. Interestingly, this compound did not interact strongly with CT DNA. It was shown that its interaction with plasmid (pBR322) DNA (binding to CCC or Form I) is different from that of cisplatin. It was demonstrated that it interacted with HSA in a moderate and reversible way which may be an advantage to the antitumor activity of this complex in vivo. These and previous results obtained in our laboratories warrant further studies on iminophosphorane complexes of gold(III) and platinum(II) as anticancer agents.

Supplementary Material

Highlights for review.

-

-

Synthesis of the first water-soluble iminophosphorane(IM) ligand

-

-

Preparation of Pt(II) and Pd(II) compounds stable in physiological media. Gold (III) compound decomposes to an stable N,N- cytotoxic gold(III) derivative

-

-

Pt(II)-IM and N,N-Au(III) more cytotoxic than cisplatin to leukemia (cell death by necroptosis) and human prostate cancer cell lines and to cisplatin resistant leukemia cell lines, and less toxic to normal lymphocytes

-

-

Pt(II) shows an interaction with DNA weaker and different than that of cisplatin

-

-

All complexes interact with HSA faster than cisplatin (fluorescence spectroscopy) and the interaction of Pt(II) and Pd(II) complexes with HSA was evaluated for the first time by ITC (Isothermal Titration Calorimetry)

-

-

Interaction of Pt(II) derivatives with HAS reversible by low pH or addition of a metal chelator (advantageous for their possible effects in vivo)

Acknowledgements

We thank the financial support of a grant from the NIH-National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), SC2GM082307 (M.C.) and a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation SAF2010-14920 (I.M.). We thank Prof. Andrzej Jarzecki (Brooklyn College) for his help with the DFT calculations of compounds 2–4 and students Farrah Benoit and Malgorzata Frik for their assistance with some fluorescence measurements. We also thank Dr. Esteban P. Urriolabeitia for helpful discussions on the synthesis of ligand 1.

Abbreviations

- ABB

annexin binding buffer

- 7-AAD

7-Amino-Actinomycin

- CD

circular dichroism

- COD

cyclooctadiene

- CT

calf thymus

- DFT

density functional theory

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetracaetic acid

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- Hepes

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- HQuinala

N-(8-quinolyl)alanine-carboxamide

- HQuinpy

N-(8-quinolyl)pyridine-2-carboxamide

- HSA

human serum albumin

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethulthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- phen

1,10-phenantroline

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TAE

tris-acetate/EDTA buffer

- tert-BuDAD

N,N′-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)2,3-butanediimine

- terpy

2,2’,6’,2’’-terpyridine

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- tmeda

N,N,N’,N”-tetramethylethylenendiamine

- TMRE

tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester

- TPA

1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Thayer AM. Platinum drugs take their toll. Chem. Eng. News. 2010;88(26):24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelland L. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sava G, Bergamo A, Dyson PJ. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:9069–9075. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10522a. and refs. therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhar S, Lippard SJ. Current status and mechanism of action of platinum-based drugs. Ch 3. In: Alessio E, editor. Bioinorganic Medicinal Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; 2011. pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Guo XZ. New trends and future developments of platinum-based antitumor drugs. Ch 4. In: Alessio E, editor. Bioinorganic Medicinal Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; 2011. pp. 97–149. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aleman J, del Solar V, Alvarez-Valdes A, Rios-Luci C, Padron JM, Navarro-Ranninguer C. MedChemComm. 2011;2:789–793. and refs. therein. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berners-Price SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:804–805. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrer NJ, Woods JA, Salassa L, Zhao Y, Robinson KS, Clarkson G, Mackay FS, Sadler PJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:8905–8908. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berners-Price SJ. Gold-based therapeutic agents. A new perspective. Ch 7. In: Alessio E, editor. Bioinorganic Medicinal Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; 2011. pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serrano FA, Matsuo AL, Monteforte PT, Bechara A, Smaili SS, Santana DP, Rodrigues T, Pereira FV, Silva LS, Machado J, Jr, Santos EL, Pesquero JB, Martins RM, Travassos LR, Caires ACF, Rodrigues EG. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:296–311. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-296. and refs. therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olzewski U, Clafeey J, Hogan M, Tacke M, Zeillinger R, Bednarski P, Hamilton G. Invest. New Drugs. 2011;29:607–614. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9395-5. and refs. therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Oliveira Silva D. Anti-Cancer Agents in Med. Chem. 2010;10:312–323. doi: 10.2174/187152010791162333. and refs. therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shyder SD, Fu Y, Habtemariam A, van Rijt SH, Cooper PA, Loadman PM, Sadler PJ. Med. Chem. Comm. 2011;2:666–668. and refs. therein. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasser G, Ott I, Metzler-Nolte N. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:3–25. doi: 10.1021/jm100020w. and refs. therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vela L, Contel M, Palomera L, Azaceta G, Marzo I. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011;105:1306–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaik N, Martinez A, Augustin I, Giovinazzo H, Varela A, Aguilera R, Sanaú M, Contel M. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:1577–1587. doi: 10.1021/ic801925k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilpin KJ, Henderson W, Nicholson BK. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2009;362:3669–3676. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown SDJ, Henderson W, Kilpin KJ, Nicholson BK. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2007;360:1310–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguilar D, Contel M, Urriolabeitia EP. Chem. A. Eur J. 2010;16:9287–9296. 2010. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguilar D, Contel M, Navarro R, Soler T, Urriolabeitia EP. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009;694:486–493. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aguilar A, Contel M, Navarro R, Urriolabeitia EP. Organometallics. 2007;26:4604–4611. [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Berkel SS, van Eldijk MB, van Hest JCM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:8806–8827. doi: 10.1002/anie.201008102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bittner S, Assaf Y, Krief P, Pomerantz M, Ziemnicka BT, Smith CG. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:1712–1718. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drew D, Doyle JR, Shaver AG. Inorg. Synth. 2007;13:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang D, Yang CT, Randford JD, Vittal JJ. Dalton Trans. 2003:4749–4753. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa R, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Peralta JE, Jr, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JN, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09, Revision A.1. Wallingford CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez-Royuela N, Perez-Galan P, Galan-Malo P, Yuste VJ, Anel A, Susin SA, Naval J, Marzo I. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1746–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alley MC, Scudiero DA, Monks A, Hursey ML, Czerwinski MJ, Fine DL, Abbott BJ, Mayo JG, Shoemaker RH, Boyd MR. Cancer Res. 1988;48:589–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vicente J, Abad JA, Clemente R, Lopez-Serrano J, Ramirez de Arellano MC, Jones PG, Bautista D. Organometallics. 2003;22:4248–4259. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falvello LR, Gracia MM, Lazaro I, Navarro R, Urriolabeitia EP. New J. Chem. 1999:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avis MW, Elsevier CJ, Veldman N, Kooijman H, Spek AL. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:1518–1528. doi: 10.1021/ic950748w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker J, Jarzecki AA, Pulay P. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998:1412–1424. [Google Scholar]

- 33.González-Pantoja JF, Stern M, Jarzecki AA, Royo E, Robles-Escajeda E, Varela-Ramírez A, Aguilera RJ, Contel M. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:11099–11110. doi: 10.1021/ic201647h. and refs. therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elie BT, Levine C, Ubarretxena-Belandia Iban, Varela A, Aguilera R, Ovalle R, Contel M. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009:3421–3430. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200900279. and refs. therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Natile G, Arnesano F. Coord. Chem Rev. 2009;253:2070–2081. and refs. therein. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siddik ZH. Oncogene. 2003;22:7265–7279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thapa RJ, Basagoudanavar SH, Nogusa S, Irrinki K, Mallilankaraman K, Slifker MJ, Beg AA, Madesh M, Balachandran S. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;14:2934–2946. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05445-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caradonna JP, Lippard SJ, Gait MJ, Singh M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:5793–5795. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dabrowiak JC. Metals in medicine. John Wiley and Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu HK, Sadler PJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:349–359. doi: 10.1021/ar100140e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruíz J, Cutillas N, Vicente C, Villa MD, López G, Lorenzo J, Avilés FX, Moreno V, Bautista D. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:7365–7376. doi: 10.1021/ic0502372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao E, Zhu M, Liu L, Huang Y, Wang L, Shi S, Chuyue ZW, Sun Y. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:3261–3270. doi: 10.1021/ic902176e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quiroga AG, Pérez JM, López-Solera I, Masaguer JR, Luque A, Roman P, Edwards A, Alonso C, Navarro-Ranninger C. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:1399–1408. doi: 10.1021/jm970520d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mansouri-Torshizi H, I-Moghaddam M, Divsalar A, Saboury AA. Biorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:9616–9625. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paul AK, Mansouri-Torshizi H, Srivastava TS, Chavan SJ, Chitnis MP. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1993;50:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(93)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blank CE, Dabrowaik JC. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1984;21:21–29. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(84)85036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cutts SM, Masta A, Panousis C, Parsons PG, Sturm RA, Phillips DR. Drug- DNA Interact. Protocols. 1997;90:95–106. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-447-X:95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Messori L, Orioli P, Tempi C, Marcon G. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;281:352–360. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang T, Tu C, Zhang J, Lin L, Zhang X, Liu Q, Ding J, Xu Q, Guo Z. Dalton Trans. 2003:3419–3424. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sherman SE, Lippard SJ. Chem Rev. 1987:1153–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi Y, Liu SA, Kerwood DJ, Goodisman J, Dabrowiak JC. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012;107:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Timerbaev AR, Hartinger CG, Aleksenko SS, Keppler BK. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2224–2248. doi: 10.1021/cr040704h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lacowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer; 2006. Ch 8; pp. 238–266. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ivanov AI, Christodoulou J, Parkinson JA, Barnham KJ, Tucker A, Woodrow J, Sadler PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14721–14730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saboury AA, Chem J. Thermodynamics. 2003:1975–1981. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sokolowska M, Wszelaka-Rylik M, Poznański J, Bal W. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rezaei Behbehani G, Divsalar A, Saboury AA, Faridbod F, Ganjali MR. J. Therm. Anal. Cal. 2009;96:663–668. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martínez A, Suálrez J, Shand T, Magliozzo RS, Sálnchez-Delgado RAJ. Inorg. Biochem. 2011:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kratochwil NA, Huber W, Muller F, Kansy M, Gerber PR. Biochem. Pharma. 2002;64:1355–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan L, Wang X, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, Guo Z. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.