Abstract

Background

Microvolt-level T-wave alternans (MTWA) measured by the spectral method is a useful risk predictor for sudden cardiac death because of its high negative predictive value. MTWA analysis software selects a segment of the ECG that encompasses the T-wave in most individuals, but may miss the T-wave end in patients with QT prolongation.

Hypotheses

1) In patients with QT prolongation, adjustment of the T-wave window will increase the sensitivity of MTWA detection. 2) The extent of T-wave window adjustment needed will correspond to the degree of QT prolongation.

Methods

Using data from long QT syndrome patients, including QTc < 0.45 s (normal), 0.45–0.49 s (moderate prolongation), and ≥ 0.50 s (severe prolongation), MTWA analysis was performed before and after T-wave window adjustment.

Results

Of 119 patients, 74% required T-wave window adjustment. There was a stronger association between the magnitude of the T-wave offset and the unadjusted QT than between the magnitude of the T-wave offset and QTc (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.690 vs. 0.485 respectively, p < 0.05). Of 99 initially negative MTWA results, 4 became non-negative after adjustment of the T-wave window (p < 0.05). All 8 initially positive studies and 12 initially indeterminate studies remained positive and indeterminate, respectively.

Conclusions

T-wave window adjustment can enable detection of abnormal MTWA that otherwise would be classified as “negative” or “normal”. Newly-developed T-wave window adjustment software may further improve the negative predictive value of MTWA testing and should be validated in a structural heart disease population.

Keywords: T wave alternans, spectral method, QT prolongation, long QT syndrome, sudden cardiac death

Microvolt-level T-wave alternans (MTWA), which reflects heterogeneities of repolarization1, has been used to predict risk of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in patients with structural heart disease2. In the structural heart disease population, patients with negative MTWA results have a much lower risk of sustained ventricular tachycardia and death than do patients with non-negative MTWA results2; 3. In some settings, a negative MTWA test is used to identify a low-risk subset of patients with reduced ejection fraction, who may not require implantation of an automatic defibrillator. Currently, however, MTWA is not widely used, primarily due to clinicians’ concern that, by withholding ICD therapy in patients with negative MTWA results, they may “miss” patients who remain at risk of life-threatening arrhythmic events. In this regard, a reduction in the number of false negative results may greatly enhance the clinical utility of MTWA.

While the standardized algorithm for MTWA detection has been clinically validated in a number of prospective studies involving patients with structural heart disease, the performance of MTWA has not been studied specifically in patients with a prolonged QT interval. The software used to detect MTWA (Cambridge Heart, Tewksbury, MA) chooses a segment of the ECG that encompasses the T-wave in most individuals. However, in patients with marked QT prolongation, a portion of the distal T-wave may occur outside of this window (figure 1). Thus, the standard software might miss MTWA in a patient with QT prolongation. Since QT prolongation does occur in a minority of structural heart disease patients, it is important to find out whether newly developed software which allows adjustment of the T-wave window can enable detection of MTWA in the setting of QT prolongation.

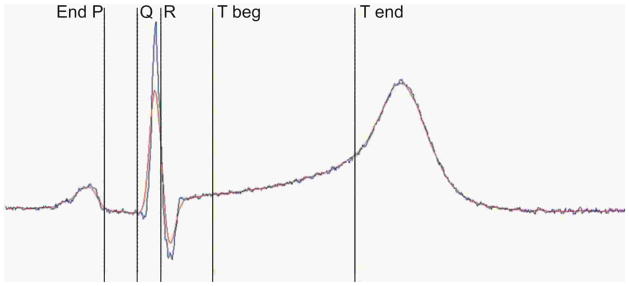

Figure 1. The Automatically-Determined T-wave Window in a Patient with Severe QT Prolongation.

Figure 1 shows an example of an automatically positioned T-wave window, marked by the caliper labeled “Tbeg” to the caliper marked “Tend” in a patient with severe QT prolongation (> 500 ms). Note that in this instance, the late portion of the T-wave occurs outside of the T-wave window.

We hypothesized that, 1) in patients with moderate to severe QT prolongation, adjustment of the ECG segment to be examined (so as to encompass the end of the T-wave) would allow detection of MTWA in some patients in whom the MTWA result is negative using the standard software and 2) the extent to which the T-wave window should be offset would correspond to the degree of QT prolongation. To prove these hypotheses, we sought a large group of patients with QT prolongation. Thus, we performed the study using data obtained from patients being evaluated for long QT syndrome (LQTS). The objective of this study was to test the stated hypotheses, not to assess the clinical value of MTWA in LQTS.

Methods

Patient population

In order to have a population enriched with long QT intervals, we used de-identified previously collected data from our ongoing long QT syndrome family study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Committee, and all subjects had given written informed consent. Subjects were included if 1) QT interval was normal but a LQTS genotype was present, or if a screening rate-corrected QT interval (QTc) using Bazett’s formula at rest was 0.45–0.49 s (moderate prolongation) or ≥ 0.50 s (severe prolongation). Patients with baseline QTc ≥ 0.45 s were included regardless of genotype status.

Further ECG analysis

For the current analysis, heart rate and QT intervals were re-measured from the digital recordings made at the time of exercise testing, in an upright position, immediately prior to the onset of exercise. QT and heart rate were measured, and rate-corrected QT (QTc) was calculated using Bazett’s formula.

MTWA analysis

Digital MTWA recordings were processed on a HearTwave II Alternans Processing System (Cambridge Heart, Tewksbury, MA). Results classified by the automated reader were compared using standard analysis vs. T-wave window-adjusted analysis. The standard alternans processing software sets the beginning of the T-wave at the J point plus 60 ms. The end of the T-wave is computed as a function of the preceding RR interval with clipping measures in place to ensure that the window does not include the P wave of the following beat. Thus, the width of the window shortens as heart rate increases and lengthens as heart rate decreases. For the current study, the digital electrocardiographic data were displayed with calipers that indicate the automatic positioning of the T-wave window. Using customized software, the investigator (ESK) then moved the onset of this T-wave window so that it would encompass the entire T-wave. The position of the window with respect to the T-wave was confirmed by visual inspection in multiple leads and complexes across the full range of heart rates. The width of the window varied with heart rate as described above. The T-wave offset (in msec) was defined as the time period by which the window was manually moved forward from the automatically set position. In no case was the window moved backward (toward the QRS complex).

Statistical methods

To test hypothesis 1, the degree of concordance/discordance between the two methods was assessed by using the p-value from the chi-square approximation to the McNemar test for matched pairs. By the nature of the customized software we hypothesized that there would be few cases if any in which the standard software was positive for MTWA and the customized software is negative. To test hypothesis 2 we assessed the relationship between T-wave offset and QT and between offset and QTc using the Spearman coefficient. Also we used the Kruskal-Wallis test to assess differences in offset between the three QTc groups and subsequently performed Wilcoxon individual two-sample tests to assess the difference between individual groups. The Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons between groups. In addition, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to assess differences in maximum negative heart rate between the standard and adjusted t-wave windows within each of the three QTc groups.

Results

One hundred nineteen subjects met inclusion criteria and had accessible stored digital data. Baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. Seventy-two were female, 43 had a history of syncope, 5 had history of cardiac arrest, and 48 were on beta-blocker therapy at the time of testing. (Because many of the tests were performed at the time of initial diagnostic assessment, most of the patients were not yet on beta-blockers.) The mean QTc was 0.48 ± 0.05 seconds, range 0.37 to 0.67. According to the unadjusted MTWA analysis, there were 99 negative (83%), 12 indeterminate, and 8 positive results.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| QTc <0.45 s (N=17) | QTc 0.45–0.49 s (N=60) | QTc ≥0.50 s (N=42) | All Subjects (N=119) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.6±15.4 | 33.9±17.0 | 30.4±14.5 | 32.6±15.9 |

| range | 15–66 | 6–80 | 6–61 | 6–80 |

| Gender female | 8 (47%) | 37 (62%) | 27 (64%) | 72 (61%) |

| Heart Rate (BPM) | 78.2±17.6 | 81.2±15.0 | 81.1±15.2 | 80.7±15.4 |

| range | 57–117 | 51–113 | 45–116 | 45–117 |

| QT (sec) | 0.38±0.04 | 0.41±0.04 | 0.46±0.05 | 0.42±0.05 |

| range | 0.31–0.43 | 0.34–0.50 | 0.39–0.61 | 0.31–0.61 |

| Syncope | 8 (47%) | 15 (25%) | 20 (48%) | 43 (36%) |

| Cardiac Arrest | 1 (5.9%) | 3 (5.0%) | 1 (2.3%) | 5 (4.2%) |

| Beta-Blocker | 7 (41%) | 21 (35%) | 20 (48%) | 48 (40%) |

MTWA analysis and the effect of QT interval on the T-wave adjustment

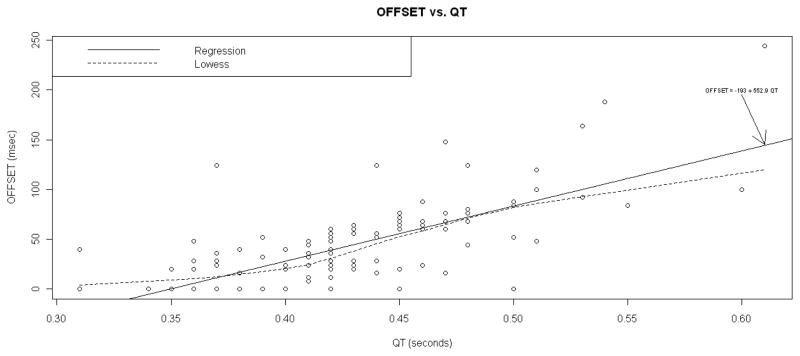

In 88 patients (74%), the T-wave window required adjustment (i.e. the offset was greater than 0). The mean T-wave offset was 40.4 ± 42.6 msec (range 0–244). The extent of T-wave offset was different between the QTc groups (mean and median offset 21.9 and 0 msec in the normal QTc group, 28.6 and 24.0 in the moderate prolongation group, 64.8 and 56.0 in the severe prolongation group). The difference in offset between the groups was statistically significant (p = 0.0002 for normal versus severe and p < 0.0001 for moderate versus severe QTc prolongation). The magnitude of the T-wave offset was better predicted by the unadjusted QT interval than by the QTc interval (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.690, p<0.0001 vs. 0.485, p<0.0001). Figure 2 shows the timing interval by which the T-wave window was advanced (offset) versus the QT interval. Defining “missing the apex” as having the automatic T-wave window end on or before the apex of the T-wave, we found that the automatic window failed to include the T-wave apex in 6 individuals: 5 out of 10 or 50% of those requiring an offset ≥ 100 ms, and 1 out of 30 (3.3%) requiring an offset of 50–100 ms (that individual had an offset of 92 ms). An example of “missing the apex” is shown in figure 1.

Figure 2. T-Wave Offset versus QT Interval.

Figure 2 shows the timing interval by which the T-wave window was advanced (offset), in milliseconds, versus the unadjusted QT interval in seconds.

Effect of adjusting the T-wave window on MTWA results

Of 99 negative MTWA results using conventional software, 4 became non-negative after adjustment of the T-wave window, with 2 becoming positive and 2 becoming indeterminate. All 8 initially positive studies and all 12 initially indeterminate studies remained positive and indeterminate, respectively. The adjusted software yielded more non-negative tests than did the conventional software, p<0.05 by the McNemar test, both for the total population and when limited to the patients with moderate to severe QTc prolongation. The effect of T-wave window adjustment on maximum negative heart rate and on detection of sustained MTWA is shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Effect of T-Wave Window Adjustment on MTWA Measurements

| QTc < 0.45 s (N=17) | QTc 0.45–0.49 s (N=60) | QTc ≥ 0.50 s (N=42) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STD | ADJ | P | STD | ADJ | P | STD | ADJ | P | |

| Maximum negative HR (median) | 115 | 115 | 0.750 | 117.5 | 115.5 | <0.01 | 116 | 109 | <0.01 |

| Sustained MTWA, N (%) | 5(29.4) | 5(29.4) | 8(13.3) | 9(15.0) | 6(14.3) | 8(19.0) | |||

| Onset HR of sustained MTWA (median) | 121 | 116 | 112 | 111 | 118.5 | 116.5 | |||

STD: standard automatic T-wave window

ADJ: manually adjusted T-wave window

P: P value from the Signed Rank test for paired data

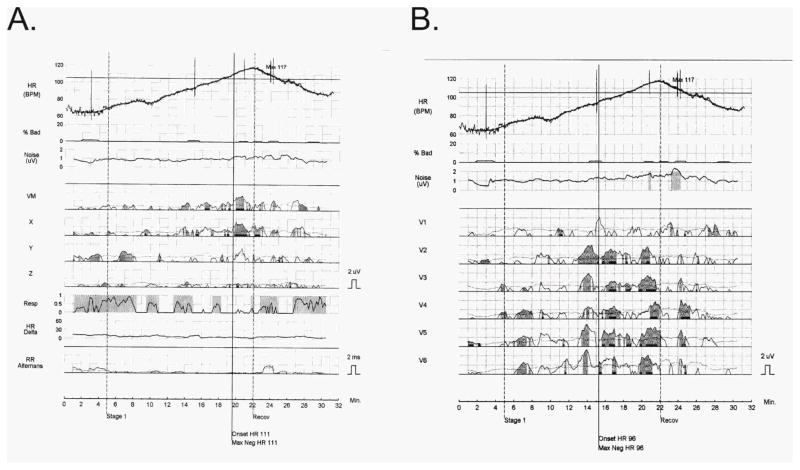

One of the tests which converted from negative to positive is shown in figure 3. Figure 4 shows the T-wave windows for the same patient (baseline QT 470 ms, QTc 490 ms, required T-wave window offset 68 ms), before and after manual adjustment. In this patient and in the other patient (baseline QT 510 ms, QTc 550 ms, required offset 100 ms) whose tests converted from negative to positive, re-analysis after adjustment of the T-wave window revealed sustained MTWA at an onset heart rate below 110 bpm. In another case (QT 420 ms, QTc 480 ms, offset 28 ms) previously classified as negative, reanalysis revealed non-sustained MTWA, reducing the maximum negative heart rate from 125 to 99 bpm (yielding an indeterminate result). The fourth case (QT 500 ms, QTc 540 ms, offset 52 ms), which converted from negative to indeterminate, was technically poor due to noise. In this case, reanalysis resulted in reassignment of the maximum negative heart rate from 111 to 101 bpm, but it is unlikely that this non-negative result would have corresponded to increased risk, since noise was the reason for indeterminacy. All four patients whose studies were reclassified fell into the moderate or severe QT prolongation groups.

Figure 3. MTWA Analyzed before and after T-Wave Window Adjustment.

Figure 3 shows one of the tests which converted from negative to positive. In the left panel is MTWA analyzed using standard software. At the top is the heart rate profile during exercise and cool-down, with a maximum heart rate of 117/min. From top to bottom, the next tracing shows a low level of “bad” (ectopic) beats, and the next shows an acceptably low level of noise. Below these tracings are the vector magnitude and X, Y and Z leads. Note that in VM and X there is sustained MTWA which begins at an onset heart rate of 111/min as determined by the automatic reader, consistent with a negative study. In the right panel is MTWA reanalyzed after T-wave window adjustment. Note that the automatic reader has established the onset of MTWA at a heart rate of 96/min, consistent with a positive study.

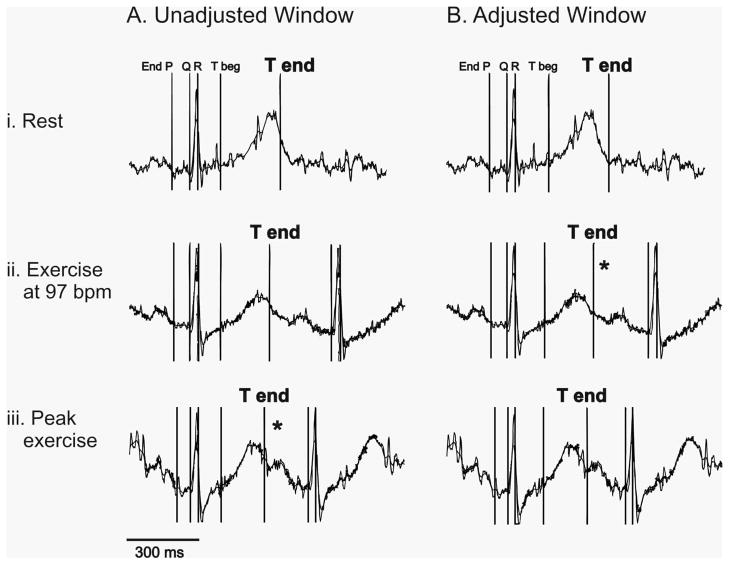

Figure 4. The T-Wave Window during Rest and Exercise, before and after Adjustment.

Figure 4 shows the automatically generated (panel A) and manually adjusted (panel B) T-wave windows for the patient whose MTWA results appear in figure 3, (i) at rest, (ii) during exercise at heart rate 97 bpm, and (iii) at peak exercise with heart rate 117 bpm. Note that the T-wave window was manually adjusted at rest (panel B, top) and that the width of this window was then automatically shortened by the software as heart rate increased, so as to avoid including the P wave of the following beat. The asterisk indicates that MTWA was observed during exercise at 97 bpm after adjustment of the T-wave window; MTWA was also present at peak exercise both before and after T-wave window adjustment.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that 1) automatic software for assessing MTWA may “miss” a distal portion of the T-wave, 2) this problem is more likely to occur as the QT interval prolongs, and 3) appropriate adjustment of the T-wave window can lead to detection of abnormal MTWA that otherwise would be classified as “negative” or “normal” in a small percentage of subjects. Although MTWA is not prevalent in the congenital LQTS population, we were able to use data from this population to investigate the concept that adjustment of the T-wave window may be necessary when QT prolongation exists in patients undergoing MTWA analysis.

Patients with congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS) have abnormal repolarization and have been observed to have visible T-wave alternans immediately preceding episodes of torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia4. Yet, efforts to detect MTWA in patients with LQTS have shown only a prevalence of about 18–20% and no clear correlation with increased risk5–7. We chose to use the LQTS population in this proof-of-concept study since they provided a relatively large sample of recordings with QT prolongation.

The more relevant population in which to test the value of T-wave window adjustment will be the structural heart disease population. Accurate risk stratification can direct defibrillator implantation toward patients who stand to benefit from this life-saving treatment, while limiting exposure of low-risk patients to device-related adverse events (and unnecessary cost). Among risk predictors for sudden cardiac death, MTWA has been one of the most promising. One of the advantages of MTWA testing is its high negative predictive value. To optimize the sensitivity of MTWA testing and improve its negative predictive value even further, it may be necessary to adjust the T-wave window in the minority of structural heart disease patients with QT prolongation, so as to encompass the entire T-wave, especially the T-wave apex, in the MTWA analysis.

Including the T-wave apex is particularly important in risk-stratifying patients with chronic structural heart disease. Although there are numerous reports of ST-segment alternans during acute ischemia, whether from Prinzmetal’s angina or from acute coronary occlusion during balloon angioplasty 8,9,10,11,12,13,14, studies of patients with stable structural heart disease have pointed to alternans within the T-wave as a risk predictor of ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death15,16,17,18. In basic studies, action potential alternans seems to involve phase 2 and, more commonly, phase 3 of the action potential1. Therefore it is likely very important to include the apex of the T-wave in MTWA analysis, even if there is a theoretical possibility of missing some alternans in the ST segment. In our study, we found that the automatic algorithm window failed to include the T-wave apex in 5 of 10 individuals requiring an offset ≥ 100 ms and in 1 other individual, whose required offset was 92 ms.

Various strategies could be used to address the problem of “missing” the latter part of the T-wave. An algorithm could be developed to automatically adjust the T-wave window according to the baseline QT interval, but there is considerable variation in the relationship between baseline QT interval and required window adjustment, so even a sophisticated automatic algorithm could not be relied upon to be accurate in every case. Alternatively, the software could be modified simply to generate a picture showing where the window had been placed for the analysis. A picture of the automatic placement of the T-wave window would not entirely eliminate the “black box” nature of the computerized MTWA analysis, but it would allow the reader to assess the technical adequacy of the study (similar to the way in which the current software displays of heart rate, noise, and abnormal beats allow assessment of the quality of the data). Studies in patients with reduced ejection fraction on the effect of adjusting the T-wave window on MTWA detection are warranted.

Conclusions

Automatic software for assessing MTWA can “miss” a distal portion of the T-wave, especially in patients with moderate to severe QT interval prolongation. In a small percentage of patients, appropriate adjustment of the T-wave window can lead to detection of abnormal MTWA that otherwise would be misclassified as “negative” or “normal”. Ultimately, this may improve the negative predictive value of MTWA testing, which would enhance its value for identifying patients at low risk of sudden cardiac death. The effect of such adjustment should be studied in patients with structural heart disease.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1 RR024989 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: this work was funded by a grant (PI: Kaufman) from Cambridge Heart, Inc., who manufacture the equipment used to measure T-wave alternans, and who designed and provided the software modification that allowed us to adjust the T-wave window as described in this paper. Furthermore, one author (Lahn Fendelander) is an employee of Cambridge Heart, Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Pastore JM, Girouard SD, Laurita KR, Akar FG, Rosenbaum DS. Mechanism linking T-wave alternans to the genesis of cardiac fibrillation. Circulation. 1999;99:1385–1394. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hohnloser SH, Ikeda T, Bloomfield DM, Dabbous OH, Cohen RJ. T-wave alternans negative coronary patients with low ejection and benefit from defibrillator implantation. Lancet. 2003;362:125–126. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloomfield DM, Steinman RC, Namerow PB, Parides M, Davidenko J, Kaufman ES, Shinn T, Curtis A, Fontaine J, Holmes D, Russo A, Tang C, Bigger JT., Jr Microvolt T-wave alternans distinguishes between patients likely and patients not likely to benefit from implanted cardiac defibrillator therapy: a solution to the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT) II conundrum. Circulation. 2004;110:1885–1889. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143160.14610.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz PJ, Malliani A. Electrical alternation of the T-wave: clinical and experimental evidence of its relationship with the sympathetic nervous system and with the long Q-T syndrome. Am Heart J. 1975;89:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(75)90008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman ES, Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Iyengar S, Elston RC, Schnell AH, Gorodeski EZ, Rammohan G, Bahhur NO, Connuck D, Verrilli L, Rosenbaum DS, Brown AM. Electrocardiographic prediction of abnormal genotype in congenital long QT syndrome: experience in 101 related family members. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:455–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nemec J, Ackerman MJ, Tester DJ, Hejlik J, Shen WK. Catecholamine-provoked microvoltage T wave alternans in genotyped long QT syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:1660–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.t01-1-00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitt J, Baumann S, Klingenheben T, Richter S, Duray G, Hohnloser SH, Ehrlich JR. Assessment of microvolt T-wave alternans in high-risk patients with the congenital long-QT syndrome. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2009;14:340–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2009.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RR, Wagner GS, Peter RH. ST-segment alternans in Prinzmetal’s angina. A report of two cases. Ann Intern Med. 1974;81:51–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-81-1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleinfeld JM, Rozanski JJ. Alternans of the ST segment in Prinzmetal’s angina. Circulation. 1977;55:574–577. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.55.4.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turitto G, El-Sherif N. Alternans of the ST segment in variant angina. Incidence, time course and relation to ventricular arrhythmias during ambulatory electrocardiographic recording. Chest. 1988;93:587–591. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rozanski JJ, Kleinfeld M. Alternans of the ST segment of T wave. A sign of electrical instability in Prinzmetal’s angina. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1982;5:359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1982.tb02243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joyal M, Feldman RL, Pepine CJ. ST-segment alternans during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:915–916. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(84)80233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sochanski M, Feldman T, Chua KG, Benn A, Childers R. ST segment alternans during coronary angioplasty. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1992;27:45–48. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810270111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okino H, Arima S, Yamaguchi H, Nakao S, Tanaka H. Marked alternans of the elevated ST segment during occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery in percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: clinical background and electrocardiographic features. Int J Cardiol. 1992;37:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(92)90128-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenbaum DS, Jackson LE, Smith JM, Garan H, Ruskin JN, Cohen RJ. Electrical alternans and vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:235–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401273300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narayan SM, Smith JM. Differing rate dependence and temporal distribution of repolarization alternans in patients with and without ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selvaraj RJ, Picton P, Nanthakumar K, Mak S, Chauhan VS. Endocardial and epicardial repolarization alternans in human cardiomyopathy: evidence for spatiotemporal heterogeneity and correlation with body surface T-wave alternans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:338–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayan SM. T-wave alternans and the susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:269–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]