Abstract

Selenoprotein K (SelK) is a membrane protein residing in the endoplasmic reticulum. The function of SelK is mostly unknown; however, it has been shown to participate in anti-oxidant defense, calcium regulation and in the Endoplasmic Reticulum Associated Protein Degradation (ERAD) pathway. In order to study the function of SelK and the role of selenocysteine in catalysis, we have tested heterologous expression of human SelK in E. coli. Consequently, we have developed an over-expression strategy that exploits the maltose binding protein as a fusion partner to stabilize and solubilize SelK. The fusion partner can be cleaved from SelK in the presence of a variety of detergents compatible with structural characterization and the protein purified to homogeneity. SelK acquires a helical secondary structure in detergent micelles, even though it was predicted to be an intrinsically disordered protein due to its high percentage of polar residues. The same strategy was successfully applied to preparation of SelK binding partner - selenoprotein S (SelS). Hence, this heterologous expression and purification strategy can be applied to other members of the membrane enzyme family to which SelK belongs.

Keywords: Selenoprotein K, Selenoprotein S, endoplasmic reticulum associated protein degradation, ERAD, selenoproteins, selenocysteine, SelK, SelS, VIMP, oxidative stress

Introduction

Selenoproteins form a specialized family of enzymes that contain the genetically encoded amino acid selenocysteine (Sec, U). Members of the family participate in regulation of redox pathway, signaling, and synthesis of lipids and hormones, and they also protect the cells against oxidative stress [1, 2]. Selenoprotein K (SelK) was identified in 2003 as one of the 25 selenoproteins encoded in the human genome [3]. It is a membrane selenoprotein, with a critical role in development [4], protection against oxidative stress [5, 6], and longevity [7]. Information about SelK is scant—it is almost certainly an enzyme, as the vast majority of the selenoproteome utilizes Sec to catalyze reactions [8]. It partakes in oxidative defense, since overexpression of SelK in cardiomyocytes decreased the level of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) [5]. SelK was also shown to protect the cells against exogenously imposed oxidative stress [5, 6]. It is expressed in all tissues but is most abundant in spleen and immune cells [9] and is coexpressed at high levels in four brain regions, along with SelP, GPx4, SelM, SelW, and Sep15 – all selenoproteins involved in protecting cells from oxidative stress [10]. Nevertheless, the precise enzymatic reaction and the physiological function(s) of SelK are unknown. Several studies suggest that SelK is involved in calcium regulation and in the ER-assisted protein degradation (ERAD) pathway—a quality control system responsible for the dislocation of misfolded proteins from the ER for degradation in the cytoplasm [11]. A recent paper demonstrated co-immunoprecipitation of SelK with components of the ERAD protein machinery [12]. In a different study, SelK knockout mice exhibited deficiencies in calcium-related functions in the immune system [9]. A follow up study has shown that SelK undergoes proteolytic cleavage by m-calpain following Toll-like receptor activation [13] and is involved in regulation of inositol 1,4,5-tris-phosphate receptors [14].

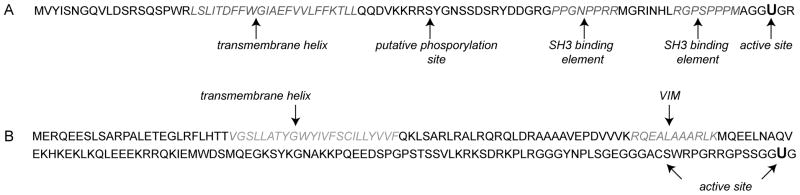

SelK is predicted to have a single pass transmembrane helix (Fig. 1A) and localizes in vivo to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [5]. The predicted transmembrane helix does not have any of the canonic motifs that lead to oligomerization of membrane proteins [15, 16]. However, its relatively high content of polar residues supports potential oligomerization [17]. The reactive Sec, located at position 92 of 94 residues in a conserved M(A/G)GGUGR sequence, is exposed to the cytoplasm [18, 19]. Uncharacteristically for selenoproteins, the Sec is not paired with a nearby Cys, Ser or Thr. In other selenoproteins, such a neighboring residue protects the easily oxidized Sec by forming a selenenylsulfide or hydrogen bond. It is possible that a hydrogen bond donor is not near in the primary sequence but is in close proximity to the Sec in the three dimensional structure or is provided by a yet-to-be-identified protein partner(s). Indeed, SelK has several motifs responsible for interactions with signaling proteins: a Src homology 3 (SH3) binding sequence [20], a second atypical SH3 domain [21], and a putative phosphorylation site at Ser 51. Pull-down assays identified the ERAD components Derlin-1, Derlin-2 and Selenoprotein S (SelS, also known as VIMP) as SelK’s binding partners. SelS, which belongs to the same family of membrane proteins, was proposed to be a reductase [22]. SelK and SelS were recently classified as members of a novel eukaryotic SelK/SelS family of proteins [12]. Members of this family have a short N-terminal ER luminal sequence; an N-terminal single pass transmembrane helix; a region rich in Gly, Pro, and charged residues; and a C-terminal active site (with either Sec or Cys). Their role is not well understood but could be broadly related to oxidative stress.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representations of SelK and SelS. (A) Human SelK has a predicted single-pass transmembrane helix; shown here is a prediction by the TMHMM program [47]. It also has two potential SH3 binding elements and a putative phosphorylation site. The reactive Sec residue resides at the C-terminal, near a conserved Arg, and is exposed to the cytoplasm. (B) Human SelS is also predicted to have a single-pass transmembrane helix. Similar to SelK, the C-terminal domain faces the cytoplasm. In addition to the transmembrane helix, it has a p97/Valosin-containing Protein (VCP)-interacting Motif (VIM), a coiled coil dimerization interface, and a disordered C-terminal region with an internal selenylsulfide bond.

Biophysical characterization of SelK remains limited, owing to difficulties in preparation of selenoproteins [23] and membrane proteins [24]. In this study, we have successfully developed an efficient protocol for overexpression and purification of the full length human SelK, in which the active site Sec was substituted with Cys (U92C). A Sec to Cys substitution in selenoproteins is commonly employed for the high-level protein production that is necessary for biophysical and structural characterization [23]. This substitution typically reduces enzymatic activity by 10 – 1000 fold but does not otherwise interfere with function or structural integrity. We show that by employing this mutation, it is possible to overexpress SelK as a fusion protein, purify it to homogeneity, and stabilize it in various detergents. This work is essential for establishing successful structural and functional characterization of SelK and for determining its mechanism of action.

We also demonstrate that the purification strategy for SelK might be generally applicable to other members of this emerging protein family. To test this hypothesis, we have employed the procedures described for SelK on its protein partner SelS. Even though SelK and SelS belong to the same family of membrane enzymes, their transmembrane segments differ significantly (Fig 1). The SelK transmembrane helix has, rather unusually, three residues that could potentially be charged at physiological pH (Glu, Asp, and Lys), while SelS has only one (Cys). Their cytoplasmic portions are disparate with the dimeric. SelS has an extended coil coiled region and a stabilizing intramolecular selenylsulfide bond, while SelK has a proline rich short segment that does appear to be stabilized by intramolecular bonds. Hence, SelS provides a suitable example to test the generality of the procedure described for SelK for other members of the family. We demonstrate that this expression and purification strategy can also be applied to SelK’s binding partner SelS.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and chemical reagents

Enzymes used for molecular biology were acquired from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). The pMHTDelta238 plasmid expressing Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease fused to the cytoplasmic maltose binding protein (cMBP) [25] was purchased from the Protein Structure Initiative: Biology Materials Repository [26]. Chromatography media was supplied by GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corporation (Pittsburgh, PA), New England Biolabs, and Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). Detergents were acquired from Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA). All other chemicals and reagents were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), and GoldBio (St. Louis, MO). All reagents and solvents were at least analytical grade and were used as supplied.

SelK expression vectors

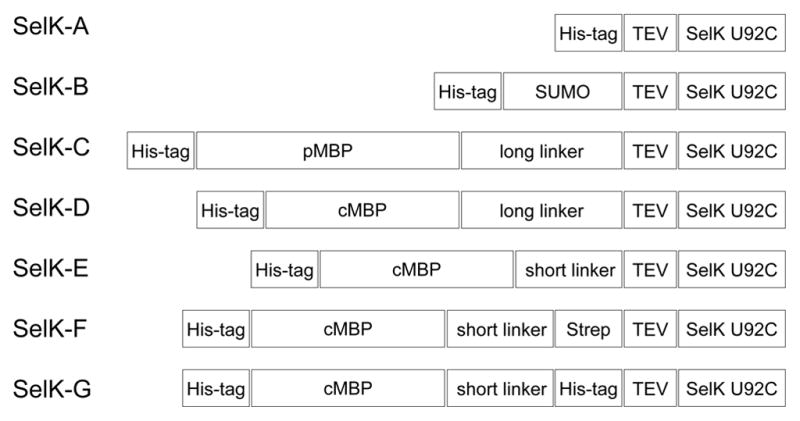

Homo sapiens SelK gene (GenBank accession no. BC013162.1) was codon optimized for expression in E. coli and the gene synthesized by DNA2.0 (Menlo Park, CA). Several SelK constructs were generated by cloning the codon-optimized SelK into various expression vectors. The gene was cloned into a pProExHTa expression vector (Life Technologies, NY) with an N-terminal hexahistidine-tag using SfoI and EcoRI, a pET28a (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) as a fusion with the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protein using BamHI and HindIII, and into pMAL-p4X (New England Biolabs) as a fusion with the periplasmic maltose binding protein (pMBP) using SacI and BamHI. pMAL-C5X (New England Biolabs) was employed to generate a series of fusions of cMBP with SelK with different linking sequence and affinity tags (Fig. 2). In all constructs, we have introduced a hexahistidine tag between I3 and E4 of cMBP. SacI and BamHI were used to generate a construct with a 16 amino acid linker, NSSSNNNNNNNNNNLG, between cMBP and SelK. AvaI and BamHI were used to generate the construct with the short linker, NSSS, between the two proteins. All constructs included a TEV protease cleavage site between SelK and the fusion tag as well as a U92C mutation in SelK. Following cleavage with TEV protease, a Gly was present before the first native amino acid in all the constructs. All the clones were verified by DNA sequencing.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representations of the expression constructs tested in this study. His-tag, hexahistidines sequence; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier protein; cMBP, cytoplasmic maltose-binding protein; pMBP, periplasmic maltose-binding protein; short linker, NSSS; long linker, NSSSNNNNNNNNNNLG; TEV, tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site (ENLYFQ/G); Strep-tag, streptavidin binding tag (WSHPQFEK); SelK U92C, homo sapiens SelK with a U92C mutation at the active site.

SelS expression vector

Homo sapiens SelS gene (GenBank accession no. GI: 45439348) was codon optimized for expression in E. coli and the gene synthesized by genescript (Piscataway, NJ). The gene was cloned into a pMAL-C5X (New England Biolabs) as a fusion with the cytoplasmic maltose binding protein (cMBP). A hexahistidine tag was introduced between residues I3 and E4 of cMBP. A short linker NSSS and a TEV cleavage site, ENLYFQS, was used to connect the two proteins. Following cleavage with TEV protease, a Ser was present before the first native amino acid. The protein contained a U188C mutation.

Protein expression screening

For protein expression, the plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) strain. Cells were grown in LB at 37 °C, with good aeration and the relevant antibiotic selection. When the Optical Density (OD) at 600 nm reached 0.5, the temperature was lowered to 18 °C, and the cells were allowed to shake at the lower temperature for an additional hour. Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) when the OD at 600 nm reached 0.7. Time points were taken periodically up to 24 hours of expression and protein expression was visualized by SDS-PAGE and western blots. The identity of the fusion proteins was verified by western blots using anti-MBP monoclonal (New England Biolabs) or His-probe (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) antibodies.

Expression and purification of SelK from a cMBP-SelK fusion

Cells were grown in LB, supplemented with 0.2% glucose at 37 °C, with good aeration and an ampicillin selection of 100 μg/mL. The temperature was changed to 18 °C about half an hour prior to induction. Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 16 h at OD reached 0.7. The cells were harvested, and the cell paste (6 g/L) was resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 200 mM sodium chloride, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 7.5 (amylose buffer), supplemented with 0.5 mM benziamidine, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 1 mM EDTA. Cells were lysed using a high-pressure homogenizer (EmulsiFlex-C5, Avestin, Ottawa, Canada). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 1 h. The supernatant was loaded on an amylose column, and the column was washed with the amylose buffer. The fusion cMBP-SelK was eluted using amylose buffer containing 20 mM maltose. The purity of the eluted cMBP-SelK was about 80%, and the most abundant contamination was cMBP. The protein was then loaded onto an immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) HisTrap FF column. The column was washed with 50 mM sodium phosphate, 200 mM NaCI, 0.067% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM), and pH 7.5 (TEV cleavage buffer). cMBP-SelK was then eluted with an imidazole linear gradient from 0–1 M imidazole in cleavage buffer. Fractions containing the cMBP-SelK fusion protein were combined and the buffer exchanged to the TEV cleavage buffer by dialysis. Cleavage of the fusion partner cMBP was carried out by adding hexahistidine-tagged TEV protease to the dialysis bag, at 4 °C for 12 h [25, 27]. The TEV protease was added at a molar ratio of 1:2 relative to the fusion protein, but concentrations as low as 1:10 were also successful. Following cleavage, the mixture was loaded again to a HisTrap FF column to remove the hexahistidine tagged cMBP and TEV. The flowthrough containing the purified SelK was concentrated to 5 mg/L and stored at 4 °C. Protein purity, as determined by 15% SDS-PAGE Tris-glycine and 16% Tris-tricine gels, was higher than 95%. Protein concentration was determined using an extinction coefficient of 15470 M−1cm−1 at 280 nm.

Size exclusion chromatography was used to exchange detergents. Approximately 200 μL of 2 mg/mL SelK was loaded on a superdex 200 10/30 GL column (GE Healthcare) and eluted at 0.4 mL/min with 50 mM sodium phosphate, 200 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.5, and the detergent of choice. The column was calibrated using GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences gel filtration protein standards: aldolase (158 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa), and ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa). The void volume was measured using blue dextran 2000.

Expression and purification of SelS U188C based on a cMBP-SelS fusion was identical to the procedure above. The protein behaves as a dimer on superdex 200 10/30 GL column (data not shown).

Mass spectroscopy

Mass spectrometry spectra were obtained using a QTOF Ultima (Waters, MA), operating under positive electrospray ionization (+ESI) mode, connected to an LC-20AD (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Protein samples were separated from small molecules by reverse phase chromatography on a C4 column (Waters XBridge BEH300), using an acetonitrile gradient from 30–71.4% with 0.1% TFA as the mobile phase, in 25 min, at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min at room temperature. Data were acquired from m/z 350 to 3,000, at a rate of 1 sec/scan.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

CD spectra of SelK and SelS were measured by using a J-810 circular dichroism spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Essex, UK) that had been calibrated using camphor sulfonic acid for optical rotation and benzene vapor for wavelength. Far-UV spectra were recorded using a 1 mm path-length cell for the 190–250 nm region at 20 °C. Samples for CD spectroscopy were prepared in 10 mM potassium phosphate, 50 mM Na2SO4, pH 7.5, and either 0.24 mM DDM, 40 mM β-OG, 25 mM SDS, or 0.072 mM LMPC. Three accumulation scans were collected for baseline, and eight accumulation scans were taken for each sample.

Results and discussion

Overexpression of SelK

To facilitate structural and biophysical characterization, we have developed bacterial overexpression and purification strategies for SelK. SelK is predicted to be a single pass transmembrane protein: a class of proteins that have a propensity to be in inclusion bodies, rather than insert in the E. coli plasma membrane. Expression level and solubility of membrane proteins are enhanced by the use of fusion proteins that can be cleaved after production [28, 29]. The selected affinity tags: a hexahistidines, SUMO, pMBP, and cMBP tags, were previously reported to be successful for the expression of membrane proteins or difficult targets [30, 31]. Since SelK’s active site is located at the C-terminal, we constructed N-terminal fusions that could be separated from SelK following expression using TEV protease (see bacterial expression vectors in Fig. 2). In each case, the Sec was mutated to a Cys (U92C) to assist the protein production. A Sec to Cys substitution is necessary to circumvent the unique requirements for Sec incorporation in proteins (it shares the TGA codon with a stop signal [30]). Since sulfur and selenium share many physicochemical properties [32], the substitution does not otherwise interfere with structural integrity, oligomerization state, or protein stability [23].

SelK fusion proteins were expressed in BL21(DE3) cells, and the expression levels using the different expression vectors were assessed by SDS-PAGE and western blot, following small-scale purifications (data not shown). The identity of the protein was further corroborated using MS/MS sequencing. The best expression was observed in the case of the cMBP fusion (also called the mature MBP), a 42 kDa protein that increases solubility and acts as a chaperone assisting protein folding. cMBP-fusion has been reported to be a particularly successful strategy for increasing expression of membrane proteins [30]. The remainder of this manuscript describes optimization of expression and purification using the cMBP-SelK fusion.

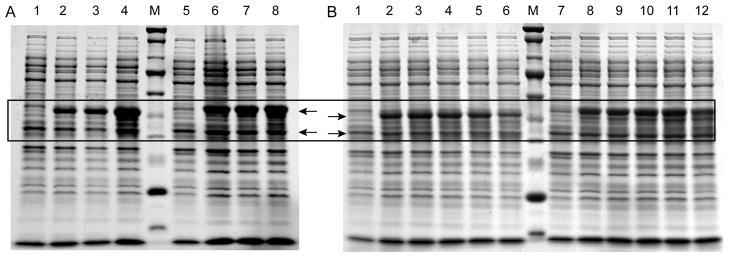

The relation between the length of linker between SelK and cMBP and in vivo proteolytic cleavage

Most MBP fusion proteins are constructed with a flexible, Asn-rich linker to improve binding of the fusion protein to the affinity column and to increase accessibility to the cleavage site by the designated protease [33]. In the case of cMBP-SelK fusion protein, we noticed significant cleavage at the linker region between the two proteins, as evidenced by the appearance of untagged cMBP (Fig. 3). Cleavage appeared to occur in vivo, as the degree of truncation did not depend on the manner in which the cells were lysed and prepared for SDS-PAGE. Cleavage was present even when the cells were lysed using SDS to denature potential proteases. Furthermore, cleavage was strongly temperature dependent, with the lowest level attained during expression at 18 °C. To reduce the occurrence of the undesired in vivo proteolytic cleavage and the resulting reduction in cMBP-SelK yield, we tested the effect of shortening the linker between the two proteins. The original long linker, NSSSNNNNNNNNNNLG (SELK-D), was changed to a shorter tetrapeptide linker SNNN (SelK-E). As Fig. 3 and subsequent figures demonstrate, we found that the resulting fusion proteins, with short and long linkers respectively, behaved identically during purification. Furthermore, the TEV cleavage site was equally accessible to the TEV protease. Nevertheless, the shorter linker (SelK-E) did reduce the extent of in vivo proteolytic cleavage significantly and was thus used exclusively. Interestingly, additional affinity tags introduced before the TEV cleavage site to assist in the purification did not increase the in vivo proteolytic cleavage rate (Fig. 2 SelK-F and SelK-G). All data shown in subsequent figures was obtained using SelK-E, since it introduces only one non-native amino acid (glycine) in SelK’s sequence and hence is least likely to perturb its function and structure.

Fig. 3.

Proteolytic cleavage of cMBP-SelK fusion in E. coli depends on the length of the linker between MBP and SelK and the expression temperature. (A) Protein expression at 18 °C of cMBP-SelK fusion with short (NSSS) and long (NSSSNNNNNNNNNNLG) linker length. Lanes 1 to 4: SelK with a short linker at 0, 4, 8, and 22 h post-induction. Lanes 5 to 8: SelK with a long linker at 0, 4, 8, and 22 h post-induction. M: Protein molecular weights standard: 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, 100, 150, 250 kDa where the 25 and 80 kDa bands triple the intensity. The arrow points to the cMBP-SelK fusion at 54 kDa and cMBP at 42 kDa. (B) cMBP-SelK with short and long linker induced at 37 °C. Lanes 1 to 6: cMBP-SelK short linker 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 22 h post-induction. Lanes 7 to 12: long linker 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 22 h post-induction. M: protein molecular weights standard as listed above. The arrow points to the cMBP-SelK fusion at 53 kDa and cMBP at 42 kDa

Detergent screening

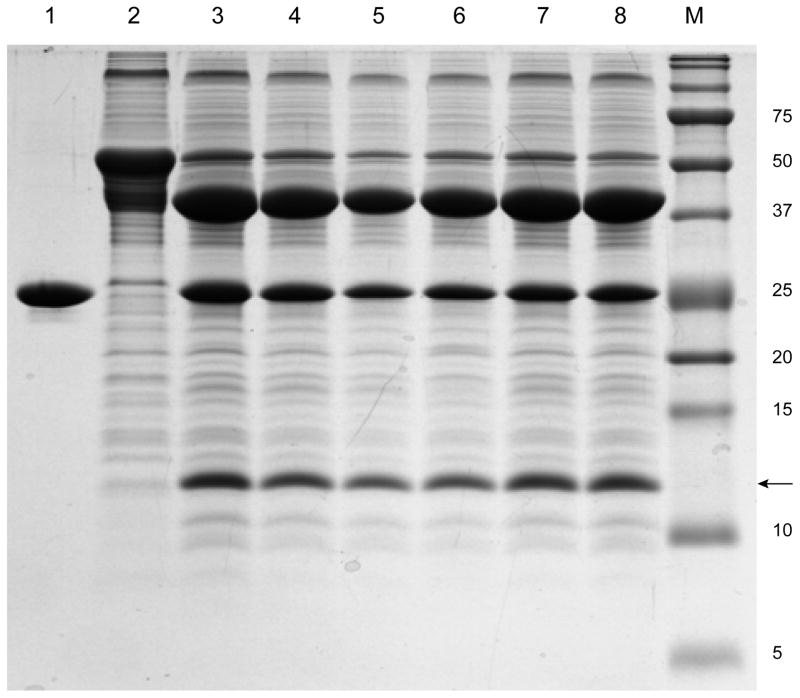

Membrane proteins are difficult study targets because invariably they require a specialized environment in which to maintain their structural and functional integrity. Key to any functional characterization of SelK is that the protein is maintained in a stable form and that aggregation is prevented by selecting the most suitable detergent, ionic strength, and stabilizing agents (i.e. glycerol, lipids etc.). Detergents affect membrane proteins’ conformation, enzymatic activity, and the ability to properly interact with affiliated proteins. The choice of detergent may vary between different applications: Crystallization requires detergents that do not completely cover the protein area, allowing it to form specific protein-protein contacts [34]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy benefits from detergents in which the spectra are well resolved [35–37]. Enzymatic activity, however, is often favored in nonionic detergents, as opposed to zwitterionic detergents [38], and certainly compared to ionic detergents. Thus, it is essential to characterize SelK in a selection of detergents. Accordingly, we surveyed the efficiency of proteolytic cleavage of SelK from its fusion partner, cMBP, by TEV protease in the presence of different detergents. They include several mild and several non-denaturing detergents: 2,2-didecylpropane-1, 3-bis-β-D-maltopyranoside (MNG-3), DDM, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (LMPC), and Triton X-100 (Fig. 4, all at concentrations of 4xCMC). These detergents are frequently used in functional studies of membrane proteins, due their ability to preserve the native structure and sustain function [39]. TEV has been previously shown to be active in these detergents [40, 41]. Successful cleavage by TEV protease was observed under all the conditions tested. SelK can also be cleaved in the absence of detergents but aggregates subsequently. Similarly, we found that the protein gradually aggregated in the presence of CHAPS and MNG-3.

Fig. 4.

Cleavage of SelK from its fusion partner cMBP by TEV protease in the presence of different detergents. Lane 1: TEV protease prior to incubation with cMBP-SelK. Lane 2: cMBP-SelK prior to incubation with TEV protease. Lane 3: Cleavage without detergent. Lane 4: Cleavage in the presence of 40 μM MNG-3. Lane 5: Cleavage in the presence of 0.48 mM DDM. Lane 6: Cleavage in the presence of 32 mM CHAPS. Lane 7: Cleavage in the presence of 0.144 mM LMPC. Lane 8: Cleavage in the presence of 0.06% Triton X-100. M: Protein molecular weights standard (the molecular mass in kDa is noted on the right). The arrow points to SelK at 10.6 kDa.

SelK purification

Usually purification strategies for cMBP fused to transmembrane proteins do not utilize detergents during extraction from cells, since the fusion protein is typically soluble [30]. MBP-SelK is soluble and localized to the cytoplasm of E. coli, but following extraction, it aggregated slowly during purification in the absence of detergents. This may be due to the unusual nature of SelK’s transmembrane helix, which has several ionizible residues (Fig. 1). To purify MBP-SelK, it was necessary to extract it in the presence of Triton X-100 or DDM (other detergents were not tested). The protein was then purified using amylose affinity chromatography. The detergent used for extraction was exchanged to the target detergent using IMAC, and SelK was cleaved from its partner cMBP by the TEV protease. Following cleavage, SelK was separated from the hexahistidines-tagged TEV and cMBP by rebinding them to IMAC beads. The final purity of the protein was above 95%. An example of a successful expression of the SelK in E. coli and subsequent purification is shown in Fig. 5A. In several purifications, two minor truncation products, in addition to the desired full-length protein, were detected. This cleavage is most likely taking place in vivo between positively charged residues, sites that are prone to proteolytic cleavage in bacterial systems.

Fig. 5.

Expression and purification of SelK-E (A) SDS-PAGE analysis. Lane 1: Crude cell extract prior to induction. Lane 2: Crude cell extract after overnight expression at 18 °C. Lane 3: Amylose column elute. Lane 4: Following exchange of detergent from 0.1% Triton X-100 to 0.067% DDM by IMAC. Lane 5: TEV protease cleavage mixture. Lane 6: SelK after the His6-tagged TEV and MBP were removed by IMAC. The arrow points to SelK. M: Protein molecular weights standard (the molecular mass in kDa is noted on the right). (B) The molecular weight of SelK detected by mass spectroscopy is 10654 Da (predicted molecular weight is 10655 Da).

The amino acid sequence of the 53 kDa fusion protein band was verified by LC MS/MS mass spectrometry analysis to be that of the full length SelK. LC-ESI-TOF mass spectrometry was employed to confirm the expected molecular weight for intact cMBP-SelK and SelK (Fig. 5B). The yield for the 53 kDa fusion protein is ~50 mg per Liter of culture. The yield of the purified, 10.6 kDa SelK is ~10 mg per Liter of culture (~1 μmol).

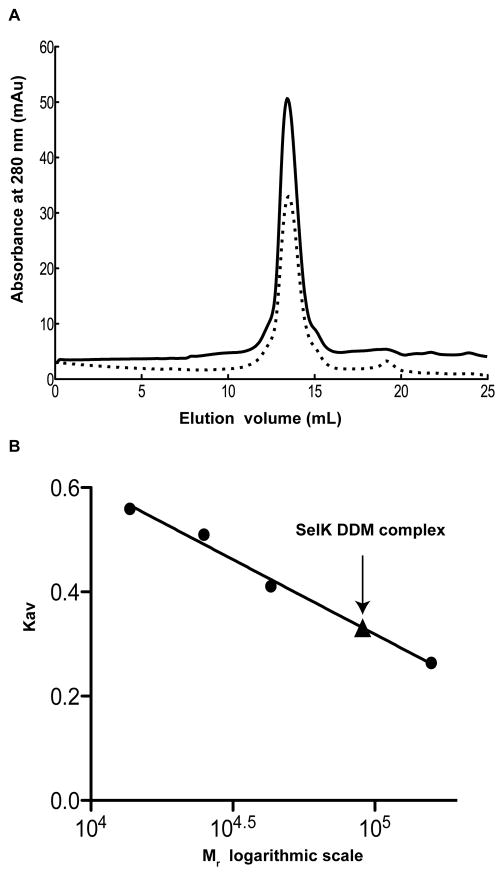

DDM-SelK micelle size

DDM is frequently used in structural characterization of membrane proteins [34, 35] and is reported here to successfully solubilize and stabilize SelK. To better evaluate its suitability for future structural studies, the molecular weight of the micelle-protein complex was measured using size exclusion chromatography. We also compared the behavior of the protein in buffer, with or without the reducing agent DTT (Fig. 6A), to remove potential intermolecular disulfide bonds. The micelle-protein complex elutes at the same location in the presence or absence of DTT. The molecular weight of the complex is 91 kDa (Fig. 6B). This value is in agreement with previous reports of the DDM detergent micelle size falling between 58 kDa to 86 kDa [42]. It is not possible to evaluate from the elution profile whether SelK elutes as a monomer or dimer since SelK is small (the molecular weight is 10655 Da). Hence, the presence of one or two copies of SelK per micelle may not cause a noticeable shift in the elution profile of the size exclusion chromatography.

Fig. 6.

Characterization of the SelK-DDM complex by size exclusion chromatography. (A) SelK DDM complex elution profile on superdex 200 in the presence (solid line) and absence of the reducing agent DTT (dotted line). (B) The molecular weight of the SelK DDM complex was determined by measuring its elution volume relative to standard proteins. The black triangle overlaid on the calibration curve corresponds to the obtained molecular weight of 91 kDa for the SelK DDM complex.

To further facilitate detergent exchange, we generated a construct of SelK, in which a streptavidin binding tag (WSHPQFEK, Strep tag) was inserted after the TEV cleavage site. The SelK retains the Strep tag after cleavage from the fusion partner, which allows its specific binding to a Strep-tactin column and exchange of detergents while bound to the column. The Strep-tagged SelK (SelK-G) behaved identically to SelK-E during purification and had a similar circular dichroism (CD) spectrum (discussed in the next section).

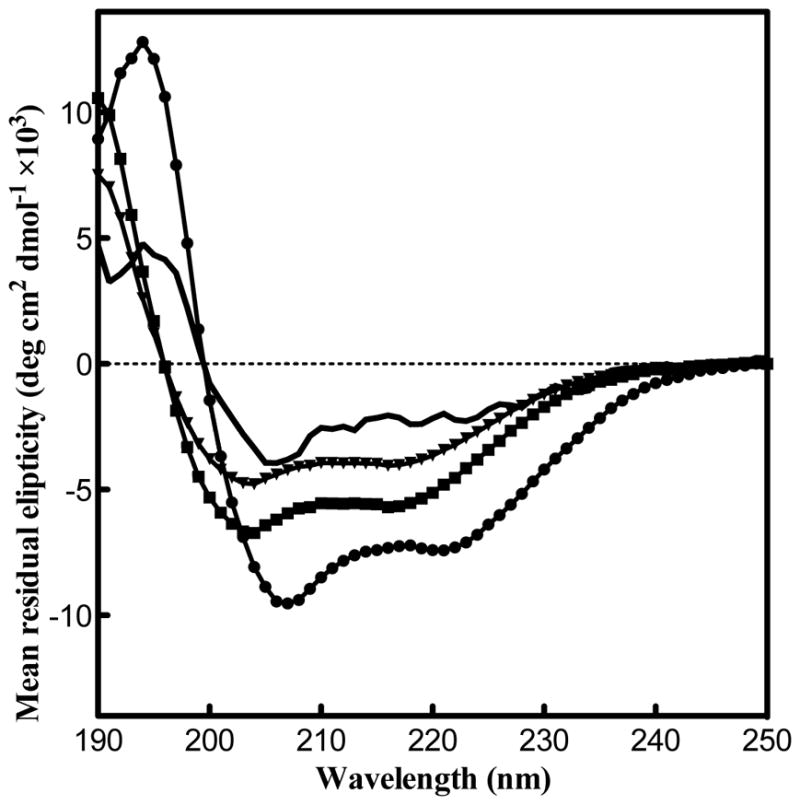

SelK secondary structure

SelK sequence is abundant in Arg, Gly, Pro, and Ser. This pattern is indicative of intrinsically disordered proteins, which are abundant in hydrophilic amino acids (Arg, Gly, Gln, Ser, Pro, Glu, and Lys) [43]. Proline-rich regions can also form left-handed polyproline II helices (PPII) [44] that have CD spectroscopy absorptions near 220 nm [45]. To probe whether SelK possesses a secondary structure, we employed CD spectroscopy. SelK CD spectrum was acquired in three detergents—DDM, β-OG, and LMPC–as they are compatible with future structural characterization and have considerably different properties [35, 46]. The detergent content was exchanged from DDM to the detergent of choice, using size exclusion as described above. As can be seen in Fig. 7, the presence of a positive band at 195 nm and negative bands at 208 and 222 nm indicates that SelK possesses a α-helix secondary structure in the three detergents. The α-helix signature is most pronounced in DDM micelles. In the presence of SDS, the CD spectrum has a reduction in helical structure and an increase in random coil content.

Fig. 7.

SelK posses a α-helical secondary structure in various detergent micelles. The helical structure is reduced in the presence of SDS. CD spectra of SelK in the presence of 0.24 mM DDM (circles), 40 mM β-OG (squares), 0.072 mM LMPC (triangles) and 25 mM SDS (solid line).

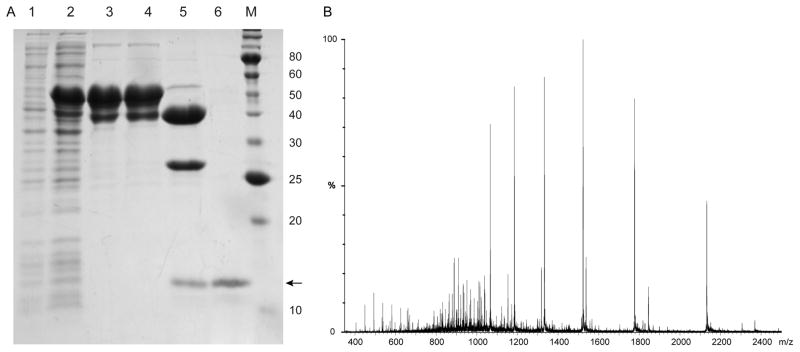

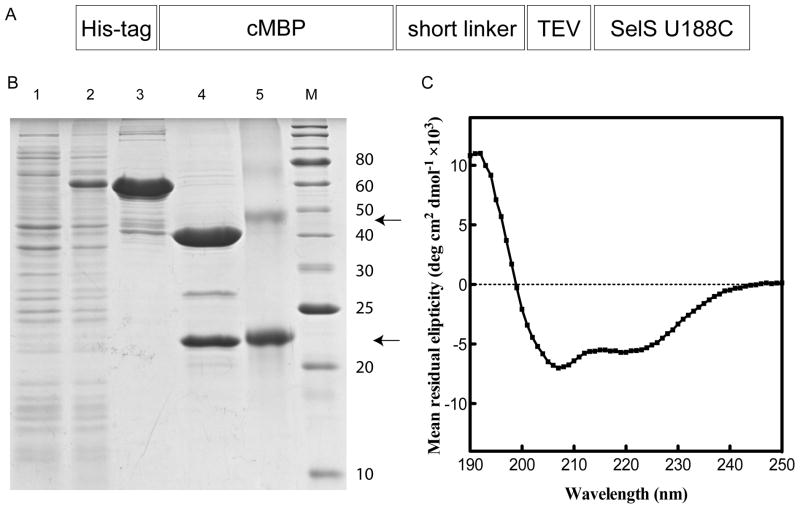

Overexpression and purification of SelS

In order to test whether the purification strategy based on extraction of MBP fusions in the presence of detergents might be generally applicable to other members of the SelK/SelS family, we have employed the procedures described for preparation of SelK on its protein partner SelS. Fig. 8 demonstrates the successful expression and purification of Homo sapiens SelS U188C using the procedure described above for SelK. The full length protein elutes as a dimer on size exclusion chromatography (data not shown) in agreement to reports on its dimerization of its soluble portion [22]. In addition to the transmembrane segment, SelS has an extended coil coiled region, as well as a disordered C-terminal domain. Hence, the CD spectrum has a signal that is mostly α-helical. The spectrum is similar to that recently published for the soluble portion, but the ratio between the two negative bands at 208 and 220 nm suggests a higher degree of α-helix content. SelS was equally well behaved in DDM micelles as SelK.

Fig. 8.

Expression and purification of SelS. (A) Schematic representations of SelS expression construct. His-tag, hexahistidines sequence; cMBP, cytoplasmic maltose-binding protein; short linker, NSSS; TEV, tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site (ENLYFQ/S); SelS U188C, homo sapiens SelS with a U188C mutation at the active site. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis. Lane 1: Crude cell extract prior to induction. Lane 2: Crude cell extract after overnight expression at 18 °C. Lane 3: Amylose column elute with buffer containing DDM detergent. Lane 4: TEV protease cleavage mixture. Lane 5: SelS after the His6-tagged TEV and MBP were removed by IMAC. The arrow points to SelS dimer and monomer (from top to bottom). M: Protein molecular weights standard (the molecular mass in kDa is noted on the right). (C) CD spectrum of SelS in the presence of 0.24 mM DDM.

Conclusions

This paper presents an expression and purification strategy for human SelK in E. coli. We find that even though SelK is rich in Gly, Pro, and charged residues, it adopts an α-helical secondary structure. This supports a view of SelK not as an intrinsically disordered protein, but rather as possessing a well-defined 3D architecture. This would agree with the presence of two SH3-binding sequences that typically have a specific geometry. Evidence of a α-helical secondary structure further supports the feasibility of structural characterization by X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy. Our studies indicate that SelK can be stabilized in a variety of detergents and acquires a α-helical secondary structure in all the detergents tested in this study. The flexibility to explore structural studies in different detergents should facilitate its characterization. We are currently in the process of exploring sample conditions for solution-state NMR studies.

A second finding reported here is that similar expression and purification strategy is successful in purifying human SelS. Both enzymes belong to the same family of eukaryotic membrane proteins but differ substantially in length, and in the polar content of their transmembrane helices. Nevertheless, the two proteins could be purified with same procedure and were stable in the presence of DDM. We suggest that it is possible that the purification strategy based on extraction of MBP fusions in the presence of detergents might be generally applicable to other members of this redox-related membrane protein family.

Highlights.

Development of expression and purification strategy for the membrane enzyme selenoprotein K in Escherichia coli

First biophysical characterization of a family member of the SelK/SelS protein family

Selenoprotein K can be solubilized in a variety of detergents

Selenoprotein K has a α helical secondary structure

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Bahnson for helpful discussions. We acknowledge service from the University of Delaware protein characterization and proteomics and mass spectrometry core facilities. We acknowledge support from an NSF CAREER award (1054447 to S.R.), MRI-R2 Grant (0959496), and grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P30RR031160-03) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P30 GM103519-03).

Abbreviations used

- SelK

selenoprotein K

- SelS

selenoprotein S

- VIMP

Valosin-containing protein (VCP) - interacting membrane protein

- TEV

tobacco etch virus

- CD

circular dichroism

- CMC

critical micelle concentration

- DDM

n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside

- LMPC

1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- MNG-3

2,2-didecylpropane-1, 3-bis-b-D-maltopyranoside

- β-OG

n-octyl-β-D-glucoside

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lobanov AV, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Eukaryotic selenoproteins and selenoproteomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1424–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu J, Holmgren A. Selenoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:723–727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kryukov GV, Castellano S, Novoselov SV, Lobanov AV, Zehtab O, Guigo R, Gladyshev VN. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003;300:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1083516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morozova N, Forry EP, Shahid E, Zavacki AM, Harney JW, Kraytsberg Y, Berry MJ. Antioxidant function of a novel selenoprotein in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Cells. 2003;8:963–971. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu CL, Qiu FC, Zhou HJ, Peng Y, Hao W, Xu JL, Yuan JG, Wang SZ, Qiang BQ, Xu CM, Peng XZ. Identification and characterization of selenoprotein K: An antioxidant in cardiomyocytes. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5189–5197. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du SQ, Zhou J, Jia Y, Huang KX. SelK is a novel ER stress-regulated protein and protects HepG2 cells from ER stress agent-induced apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;502:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai CQ, Parnell LD, Lyman RF, Ordovas JA, Mackay TFC. Candidate genes affecting Drosophila life span identified by integrating microarray gene expression analysis and QTL mapping. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellano S, Lobanov AV, Chapple C, Novoselov SV, Albrecht M, Hua DM, Lescure A, Lengauer T, Krol A, Gladyshev VN, Guigo R. Diversity and functional plasticity of eukaryotic selenoproteins: Identification and characterization of the SelJ family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16188–16193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505146102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma S, Hoffmann FW, Kumar M, Huang Z, Roe K, Nguyen-Wu E, Hashimoto AS, Hoffmann PR. Selenoprotein K knockout mice exhibit deficient calcium flux in immune cells and impaired immune responses. J Immunol. 2011;186:2127–2137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Schweizer U, Savaskan NE, Hua D, Kipnis J, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Comparative analysis of selenocysteine machinery and selenoproteome gene expression in mouse brain identifies neurons as key functional sites of selenium in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2427–2438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MH, Ploegh HL, Weissman JS. Road to ruin: Targeting proteins for degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2011;334:1086–1090. doi: 10.1126/science.1209235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shchedrina VA, Everley RA, Zhang Y, Gygi SP, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Selenoprotein K binds multiprotein complexes and is involved in the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42937–42948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.310920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Z, Hoffmann FW, Norton RL, Hashimoto AC, Hoffmann PR. Selenoprotein K Is a novel target of m-calpain, and cleavage is regulated by toll-like receptor-induced calpastatin in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:34830–34838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.265520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben SB, Wang QY, Xia L, Xia JZ, Cui J, Wang J, Yang F, Bai H, Shim MS, Lee BJ, Sun LG, Chen CL. Selenoprotein dSelK in Drosophila elevates release of Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum by upregulating expression of inositol 1,4,5-tris-phosphate receptor. Biochemistry-Moscow. 2011;76:1030–1036. doi: 10.1134/S0006297911090070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rath A, Deber CA. Surface recognition elements of membrane protein oligomerization. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2008;70:786–793. doi: 10.1002/prot.21569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walters RFS, DeGrado WF. Helix-packing motifs in membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13658–13663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605878103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li E, Wimley WC, Hristova K. Transmembrane helix dimerization: Beyond the search for sequence motifs. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2012;1818:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen CL, Shim MS, Chung J, Yoo HS, Ha JM, Kim JY, Choi J, Zang SL, Hou X, Carlson BA, Hatfield DL, Lee BJ. G-rich, a Drosophila selenoprotein, is a Golgi-resident type III membrane protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:1296–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shchedrina VA, Zhang Y, Labunskyy VM, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Structure-function relations, physiological roles, and evolution of mammalian ER-resident selenoproteins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:839–849. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li SSC. Specificity and versatility of SH3 and other proline-recognition domains: structural basis and implications for cellular signal transduction. Biochem J. 2005;390:641–653. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carducci M, Perfetto L, Briganti L, Paoluzi S, Costa S, Zerweck J, Schutkowski M, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. The protein interaction network mediated by human SH3 domains. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen LC, Jensen WJ, Vala A, Kamarauskaite J, Johansson L, Winther JR, Hofmann K, Teilum K, Ellgaard L. The human selenoprotein VCP-interacting membrane protein (VIMP) is non-globular and harbors a reductase function in an intrinsically disordered region. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:26388–26399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansson L, Gafvelin G, Arner ESJ. Selenocysteine in proteins - properties and biotechnological use. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1726:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junge F, Schneider B, Reckel S, Schwarz D, Dotsch V, Bernhard F. Large-scale production of functional membrane proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1729–1755. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8067-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blommel PG, Fox BG. A combined approach to improving large-scale production of tobacco etch virus protease. Protein Expr Purif. 2007;55:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cormier CY, Mohr SE, Zuo DM, Hu YH, Rolfs A, Kramer J, Taycher E, Kelley F, Fiacco M, Turnbull G, LaBaer J. Protein Structure Initiative Material Repository: an open shared public resource of structural genomics plasmids for the biological community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D743–D749. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Fox JD, Anderson DE, Cherry S, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. Tobacco etch virus protease: mechanism of autolysis and rational design of stable mutants with wild-type catalytic proficiency. Protein Eng. 2001;14:993–1000. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esposito D, Chatterjee DK. Enhancement of soluble protein expression through the use of fusion tags. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen HP, Mortensen KK. Soluble expression of recombinant proteins in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact. 2005;4 doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu J, Qin HJ, Gao FP, Cross TA. A systematic assessment of mature MBP in membrane protein production: Overexpression, membrane targeting and purification. Protein Expr Purif. 2011;80:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marblestone JG, Edavettal SC, Lim Y, Lim P, Zuo X, Butt TR. Comparison of SUMO fusion technology with traditional gene fusion systems: Enhanced expression and solubility with SUMO. Protein Sci. 2006;15:182–189. doi: 10.1110/ps.051812706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wessjohann LA, Schneider A, Abbas M, Brandt W. Selenium in chemistry and biochemistry in comparison to sulfur. Biol Chem. 2007;388:997–1006. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sachdev D, Chirgwin JM. Fusions to maltose-binding protein: Control of folding and solubility in protein purification. Methods Enzymol. 2000;326:312–321. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)26062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newstead S, Ferrandon S, Iwata S. Rationalizing alpha-helical membrane protein crystallization. Protein Sci. 2008;17:466–472. doi: 10.1110/ps.073263108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HJ, Howell SC, Van Horn WD, Jeon YH, Sanders CR. Recent advances in the application of solution NMR spectroscopy to multi-span integral membrane proteins. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2009;55:335–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamm LK, Liang BY. NMR of membrane proteins in solution. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2006;48:201–210. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanders CR, Sonnichsen F. Solution NMR of membrane proteins: practice and challenges. Magn Reson Chem. 2006;44:S24–S40. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.le Maire M, Champeil P, Moller JV. Interaction of membrane proteins and lipids with solubilizing detergents. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2000;1508:86–111. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(00)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prive GG. Detergents for the stabilization and crystallization of membrane proteins. Methods. 2007;41:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lundback A-K, van den Berg S, Hebert H, Berglund H, Eshaghi S. Exploring the activity of tobacco etch virus protease in detergent solutions. Anal Biochem. 2008;382:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohanty AK, Simmons CR, Wiener MC. Inhibition of tobacco etch virus protease activity by detergents. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;27:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00589-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strop P, Brunger AT. Refractive index-based determination of detergent concentration and its application to the study of membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2207–2211. doi: 10.1110/ps.051543805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uversky VN. Intrinsically disordered proteins from A to Z. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1090–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stapley BJ, Creamer TP. A survey of left-handed polyproline II helices. Protein Sci. 1999;8:587–595. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bochicchio B, Tamburro AM. Polyproline II structure in proteins: Identification by chiroptical spectroscopies, stability, and functions. Chirality. 2002;14:782–792. doi: 10.1002/chir.10153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poget SF, Girvin ME. Solution NMR of membrane proteins in bilayer mimics: Small is beautiful, but sometimes bigger is better. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2007;1768:3098–3106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]