Abstract

Age-related impairments of executive functions appear to be related to reductions of the number and plasticity of dendritic spine synapses in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Experimental evidence suggests that synaptic plasticity is mediated by the spine actin cytoskeleton, and a major pathway regulating actin-based plasticity is controlled by phosphorylated LIM kinase (pLIMK). We asked whether aging resulted in altered synaptic density, morphology, and pLIMK expression in the rat prelimbic region of the PFC. Using unbiased electron microscopy, we found a ~50% decrease in the density of small synapses with aging, while the density of large synapses remained unchanged. Postembedding immunogold revealed that pLIMK localized predominantly to the postsynaptic density where it was increased in aging synapses by ~50%. Furthermore, the age-related increase in pLIMK occurred selectively within the largest subset of prelimbic PFC synapses. Since pLIMK is known to inhibit actin filament plasticity, these data support the hypothesis that age-related increases in pLIMK may explain the stability of large synapses at the expense of their plasticity.

Keywords: Aging, synapse, prefrontal cortex, actin, electron microscopy, postembedding immunogold, perforated synapse, postsynaptic density, structural plasticity

1. Introduction

Neuronal networks in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) that mediate executive functions are known to be vulnerable to aging. While strong evidence suggests that age-related PFC dysfunction is not a result of neuronal death or outright degeneration (Peters et al., 1998), the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie vulnerability of PFC neurons to aging are only partly understood. Recent studies have demonstrated that aging may impair the functional integrity of PFC networks by altering the number, structure, and plasticity of axospinous synapses on pyramidal neurons. For example, aging results in a selective loss of small, thin-type dendritic spines on primate dorsolateral PFC pyramidal neurons, which correlates with impairments in learning (Dumitriu et al., 2010). Similar patterns of spine loss have been reported in aging rat prelimbic (PL) PFC, and it appears the remaining axospinous synapses on aged rat PL PFC pyramidal neurons have a reduced capacity for structural plasticity (Bloss et al., 2011). However, the mechanisms underlying synaptic vulnerability and resilience, as well as those mediating changes in the capacity for structural synaptic plasticity during aging remain unknown.

Experimental evidence suggests that dendritic spine plasticity is controlled by the actin spine cytoskeleton (Matus, 2000, Okamoto et al., 2004, Honkura et al., 2008). Actin dynamics are tightly regulated by upstream signaling pathways and actin-binding proteins (dos Remedios et al., 2003). A major pathway regulating actin-based plasticity within synapses is controlled by phosphorylated LIM kinase (pLIMK), which increases the stability of filamentous actin (F-actin) by inhibiting the filament severing actions of ADF/cofilin proteins via phosphorylation (Arber et al., 1998, Yang et al., 1998). In support for a prominent role in regulating structural and functional plasticity, LIMK1 knockout mice have altered synaptic morphology and plasticity (Meng et al., 2002). Furthermore, manipulation of the LIMK target cofilin modulates both synaptic potentiation (Fukazawa et al., 2003) and synaptic glutamate receptor plasticity (Gu et al., 2010, Yuen et al., 2010). Lastly, it should be noted that mutation of the LIMK gene in humans has been linked to Williams Syndrome (Tassabehji et al., 1996), a mental retardation consisting of deficits across several cognitive domains including those thought to be mediated by PFC circuitry (Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2006).

In the present study, we took an anatomical approach utilizing unbiased, quantitative postembedding immunoelectron microscopy to investigate potential age-related changes of pLIMK within the context of PL PFC synapse density and synapse size. We report here that the density of small synapses in the PL PFC was decreased by ~50% in aged rats while the density of large synapses remained unchanged between the ages. Immunogold labeling of pLIMK was abundant in PL PFC synapses and localized predominantly to the postsynaptic density (PSD), where it selectively increased in the largest subset of synapses during aging. These data provide the first evidence to connect age-related changes of PFC synapses to alterations of actin-related signaling pathways, and suggest that pathways controlling the phosphorylation state of pLIMK may explain the stability of aging synapses at the expense of their plasticity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals and tissue preparation

Male Sprague Dawley rats were purchased form Harlan (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) at 3 and 20 months of age (i.e., young and aged; n=5 per age), and were housed under standard laboratory conditions for six weeks as part of previously reported experiments (Bloss et al., 2010, Bloss et al., 2011). At ~21 months of age in this rat strain there is a ~90% survival rate of male rats, and survival rates decline precipitously several months later (Altun et al., 2007). All experiments were conducted in compliance with the NIH guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Mount Sinai School of Medicine and Rockefeller University.

Animals were perfused at 4.5 and 21.5 months of age as described (Bloss et al., 2010). Coronal sections (250 µm) encompassing the prelimbic (PL) cortex of the medial PFC (between 3.7 mm and 2.7 mm from Bregma; Figure 1A) according to (Paxinos and Watson, 2005) were prepared for immunoelectron microscopy as reported previously (Janssen et al., 2005). Due to the number of animals in our study and the limited capacity of our embedding equipment, we were unable to collect full stereological series for EM reconstructions.

Figure 1. EM sampling, disector analysis, and pLIMK immunogold.

A EM blocks encompassed rat PL PFC (black box), and serial sections were collected from layer I (white dashed lines, approximately 100 µm from layer II). B Example of axospinous synapses identified by the disector analysis (Note: black dots denote synapses contained in both planes; asterisks denote synapses contained only in 1 plane). C Representative serial images of a PL layer I synapse with pLIMK immunogold labeling. Note the prominent localization of pLIMK to the PSD (arrowheads). “ax” denotes an axonal bouton, “sp” denotes a dendritic spine. Scale bars: B 500 nm; C 200 nm.

Briefly, slices were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.125% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 µ phosphate buffer (PB) overnight at 4°C, cryoprotected via graded PB/glycerol washes at 4°C, and manually microdissected to obtain blocks containing layers I-VI of PL cortex. Blocks were rapidly freeze-plunged into liquid propane cooled by liquid nitrogen (−90° C) in a Universal Cryofixation System KF80 (Reichert-Jung, Vienna, Austria) and subsequently immersed in 1.5% uranyl acetate dissolved in anhydrous methanol at −90° C for 24 hours in a cryosubstitution unit (Leica, Vienna, Austria). Block temperatures were raised from −90°C to −45°C in steps of 4°C/hour, washed with anhydrous methanol, and infiltrated with Lowicryl resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) at −45° C. The resin was polymerized by exposure to ultraviolet light (360 nm) for 48 hours at −45° C followed by 24 hours at 0° C. Block faces were trimmed to layers I-III of the PL cortex (Figure 1A). Ultrathin sections (90 nm) were cut with a diamond knife (Diatome, Bienne, Switzerland) on an ultramicrotome (Reichert-Jung) and serial sections of at least 5 sections were collected on formvar/carbon coated nickel slot grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences).

2.2 Postembedding immungold labeling

The polyclonal antisera to pLIMK (#3841, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) was produced by immunizing animals with a synthetic peptide (R-K-K-R-Y-pT-V-V-G-N-P-Y-W-M), purified by protein A and peptide affinity chromatography, and has been previously characterized by Western blot (Misra et al., 2005, Croft and Olson, 2006, Heredia et al., 2006, Hsieh et al., 2006, Gamell et al., 2008), by light-level immunolabeling in hippocampal culture and brain tissue (Heredia et al., 2006, Spencer et al., 2008, Yildirim et al., 2008), and by pre- and postembedding immunoelectron microscopy (Yildirim et al., 2008). The pLIMK antisera recognizes phosphorylated threonine residues of both LIMK1 (Thr508) and LIMK2 (Thr505), both of which are sites known to be targeted by the Rho-family GTPase effectors PAK1 and ROCK. On Western blots, this antiserum recognizes a band corresponding to the molecular weight of LIMK1/2 (~72 kDa), which disappears with application of the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (Croft and Olson, 2006).

Postembedding immunogold labeling was performed using previously published methods (Yildirim et al., 2008) with minor modifications. Slot grids were incubated in 50 mµ glycine/ 0.1% sodium borohydride (both from Sigma, St. Louis, MO), washed several times with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) solution, blocked in TBS containing 5% human serum albumin (Sigma) and 0.1% Triton-X100 (Sigma), and incubated with anti-pLIMK (2 µg/ml) in TBS/albumin overnight at roomctemperature. Grids were then washed with TBS, blocked in TBS/albumin, and incubated with secondary anti-rabbit IgG 10 nm gold-tagged antibody (1:40; Electron Microscopy Sciences) diluted in TBS/albumin with 5 mg/ml polyethyleneglycol (Sigma). Grids were then stained with 1.5% uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in distilled H2O to enhance membrane ultrastructure, washed in distilled H2O, and allowed to air dry.

As in a previous report (Yildirim et al., 2008), two control experiments were conducted to ensure the specificity of the pLIMK antisera. First, labeling of slot grids with preimmune serum in place of pLIMK antiserum yielded very sparse gold labeling with no obvious pattern. Second, preadsorption of the immune sera with the immunizing peptide (Cell Signalling) blocked immunogold labeling.

2.3 Analysis of synapse density and structure

Serial section micrographs were taken with a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope at ×4000. Fifteen sets of serial images across the same set of 5 consecutive ultrathin sections were taken in layer I (i.e., ~100 µm from the cell-dense layer II of PL cortex; see Figure 1A) and imported into Adobe Photoshop (Photoshop CS5, version 11.0.2). To obtain a stereologically unbiased population of synapses for quantitative morphologic and immunogold distribution analysis, we utilized the disector analysis of ultrathin sections as in previous reports (Figure 1B) (Sterio, 1984, de Groot and Bierman, 1986, Tigges et al., 1996, Adams et al., 2001, Dumitriu et al., 2010). Briefly, all axospinous synapses were identified within the first two and last two images of each 5-section serial set, and counted if they were contained in the reference image but not in the corresponding look-up image. To increase sampling efficiency, the reference image and look-up image were then reversed; thus each animal included in the current study contributed synapse density data from a total of thirty disector pairs. The disector area used was 104.85 µm2, and the height of the disector was 180 nm; therefore, axospinous synapse density (per µm3) was calculated as the total number of counted synapses from both images divided by the total volume of the disector.

2.4 Quantitative pLIMK immunogold analysis

The subset of synapses identified by the disector method enabled an unbiased and quantitative analysis of pLIMK immunogold distribution within the context of synapse size. In each set of five serial images, synapses that had leading PSDs in images 2 and 4 were then followed through the remaining serial sections (i.e., new synapses in image 2 were followed through image 5, and new synapses in image 4 were followed through image 1) and analyzed for several properties. For each synapse, the following parameters were determined: 1) maximum length of the PSD and head diameter, 2) the presence or absence of perforated PSDs, and 3) the presence or absence and number of gold particles (including single particles). Gold particles were then manually assigned to one of several bins: 1) a PSD bin, which included all gold particles that lie in/on the PSD, within 30 nm of the postsynaptic membrane directly opposed to the synaptic cleft, and gold particles found within the synaptic cleft; 2) a subsynaptic bin, which included all gold particles that fall between 30–60 nm from the postsynaptic membrane; 3) a perisynaptic bin, comprised of all gold particles within 60 nm lateral to the PSD; 4) a spine cytoplasmic bin, which included all gold particles within the spine head > 60 nm from the synaptic membrane and > 30 nm from the lateral spine membrane; 5) a plasmalemmal bin, which included all gold particles within 30 nm of the lateral spine membrane; and 6) a presynaptic active zone bin, which included all gold particles within the presynaptic terminal located 30 nm from the active zone.

2.5 Statistical analyses

A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to analyze the density of PL PFC axospinous synapses and the percent of pLIMK immunogold-labeled synapses. Differences in the cumulative frequency distributions of head diameter and PSD length were analyzed with Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodnessof-fit tests (MatLab, Natick, MA). Age differences between synaptic bin distributions were compared using two-way ANOVAs and Bonferonni post-hoc tests. Rather than assigning arbitrary and subjective cut-off points for synapse size bins, a K-means cluster analysis (SPSS, Chicago, IL) of PSD size was performed to statistically and objectively divide all synapses into 3 clusters in order to compare similar structures across ages (see Table 1 for synapse cluster details). This analysis uses a single pass of the data to create 3 cluster means, and subsequent iterations assign each value to a cluster mean determined by the smallest Euclidean distance. Iteration ceases when a complete iteration does not move any of the cluster centers by a distance of more than two percent of the smallest distance between any of the initial cluster centers. This type of analysis has been used in comparable settings (Lane et al., 2008). Morphological and pLIMK immunogold labeling parameters from the PSD clusters were compared using two-way ANOVAs and Bonferonni posthoc tests. All statistics were performed with Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) unless otherwise noted, and bar graphs including error bars represent mean ± SEM. For all statistical tests, α was set at 0.05.

Table 1. PSD length cluster analysis.

PSD lengths from non-perforated synapses were subjected to a K-means cluster analysis to mathematically separate heterogeneous synapse populations into 3 size groups. In agreement with previous EM and confocal spine analyses, the majority of synapses were small, while synapses in the largest cluster were comparatively sparse.

| Synapses per Animal (Range) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSD | Min. | Max. | |||

| Cluster | (µm) | (µm) | Young | Aged | Total Synapses |

| Cluster 1 | 0.0443 | 0.2494 | 90.2 (80–98) | 48.2 (39–61) | 692 |

| Cluster 2 | 0.2502 | 0.4017 | 47.8 (41–58) | 41 (32–51) | 444 |

| Cluster 3 | 0.4043 | 0.7066 | 11 (5–15) | 13.4 (11–15) | 122 |

3. Results

3.1 Effects of aging on PL PFC axospinous synaptic density

We first asked whether axospinous synaptic densities are altered by age in the rat PL PFC. Approximately 2,900 synapses (mean = 293; range = 232–358 per animal; 5 animals per age) were identified for analysis of synapse density. Disector analysis revealed a consistent pattern of ~30% decrease in axospinous synapse density within PL PFC layer I in aged compared to young rats (mean synapse/µm3 ± SEM; young, 0.601 ± 0.010; aged, 0.436 ± 0.010; t(8) = 10.69, p < 0.0001; Figure 2A). These data are in agreement with previous reports regarding age-related changes in PL PFC dendritic spine density from these animals (Bloss et al., 2011), and moreover individual synapse density measures obtained here correlated strongly (r2 = 0.7247, p < 0.01) with dendritic spine densities on dendritic segments in layer l from PL PFC neurons obtained from these same animals (data not shown). Because of the close agreement across these microscopic techniques, we conclude these data provide strong evidence for synapse density changes on aging PL PFC neurons.

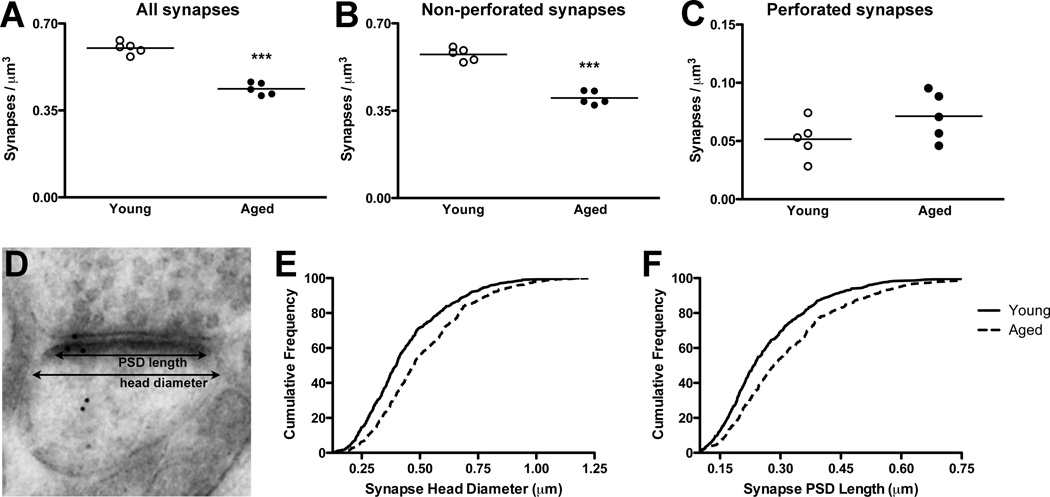

Figure 2. Age-related alterations of synapse density and morphology in PFC.

A Axospinous synapse density decreased with age by approximately 30%. B,C Similar changes were seen when the analysis was restricted to non-perforated synapses, while the density of perforated synapses was unchanged between the ages. D–F Measurements of synaptic head diameter and PSD length revealed age-related shifts towards larger synapses. ***, p < 0.0001. Graphs: circles, individual animals; line, group mean.

We next asked whether the overall reduction of axospinous synapse density was restricted or generalized across two broad synaptic subtypes, perforated or non-perforated synapses. Similar to the overall decrease of synapses, we found that the density of non-perforated synapses (mean synapse/µm3 ± SEM; young, 0.575 ± 0.011; aged, 0.401 ± 0.012; t(8) = 10.46, p < 0.0001; Figure 2B), but not perforated synapses (mean synapse/µm3 ± SEM; young, 0.050 ± 0.007; aged, 0.071 ± 0.009;t(8) =1.725, p > 0.1; Figure 2C), decreased in the aged animals. We note that because perforated synapses account for a small fraction (10–20%) of all axospinous synapses in the current study, far fewer perforated synapses were sampled than non-perforated synapses. Nevertheless, these data imply that the synapses vulnerable to aging are likely to be restricted to a population within non-perforated synapses. Conversely, these data indicate perforated synapses may be resistant to decline with aging in PFC circuits, which is consistent with experimental data from synapses on aging monkey PFC neurons (Wang et al., 2010).

3.2 Effects of aging on PL PFC synapse morphology

We next asked whether aging alters ultrastructural aspects of PL PFC synaptic morphology. We reconstructed approximately 1,400 synapses (mean = 143; range = 110–176 per animal) across serial EM sections, and for each synapse measured maximum head diameter and maximum PSD length (Figure 2D). While the range of synaptic head diameters from young and aged animals was nearly identical (young, 0.098–1.186 µm; aged, 0.102–1.240 µm), mean head diameter was significantly larger in aged animals (t(8) = 7.145, p < 0.0001; data not shown) and cumulative frequency plots revealed aging shifts the distribution of synaptic head diameters significantly to the right (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p < 3.9 ×10−9; Figure 2E). Similarly, we found that while the range of PSD lengths from synapses of young and aged animals was comparable (young, 0.044–0.852 µm; aged, 0.079–1.016 µm), mean PSD length was significantly greater in aged animals (t(8) = 7.282, p < 0.0001; data not shown) and cumulative frequency plots revealed aging moves the distribution of synaptic PSD lengths significantly to the right (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p < 8.7 ×10−8; Figure 2F). These data are consistent with previous confocal analyses of the effects of age on monkey and rat PFC dendritic spine head diameters (Dumitriu et al., 2010, Bloss et al., 2011) and further extend these observations to age-related alterations of PL PFC synaptic ultrastructure.

3.3 Effects of aging on ultrastructural distribution of pLIMK in PL PFC synapses

Qualitative examination of postembedding pLIMK in PFC synapses revealed labeling was similar to that previously described in hippocampal CA1 synapses (Yildirim et al., 2008). In both young and aged animals, gold particles were abundant in pre- and postsynaptic structures. Within presynaptic terminals, gold particles were often seen in the vesicle active zone, but also in lower quantities throughout the terminal. Postsynaptic gold particles were most abundant in the PSD, but could be found less frequently within the subsynaptic compartment of synapses and deeper within the spine head cytoplasm. To our knowledge, these data are the first to report the presence and ultrastructural distribution of pLIMK in PL PFC synapses.

For a quantitative analysis of synaptic distribution, we divided the synapse into several relevant compartments (Figure 3A) and manually assigned the gold particles during serial synaptic reconstructions. Using this approach, we asked whether aging alters the ultrastructural distribution of pLIMK labeling. We first determined that approximately 95% of reconstructed axospinous synaptic contacts were labeled by gold particles across both ages (young, 94 ± 0.9%; aged, 95 ± 1.2%; p > 0.4, data not shown). Unlabeled synapses showed a wide distribution in terms of head diameter or PSD length that did not differ between young and aged animals (head diameters: young, 0.117–0.598 µm; aged, 0.102–0.653 µm; PSD lengths: young, 0.075–0.370 µm; aged, 0.079–0.360 µm). Because such a high percentage of PL PFC synapses were immunolabeled for pLIMK, and because reductions of either pLIMK immunolabeled synapses or pLIMK molecules per synapse might represent an important biological change, we included unlabeled synapses in our analysis.

Figure 3. pLIMK is increased in the PSD of aging non-perforated synapses.

A pLIMK gold particles were assigned to synaptic bins; see Materials and Methods for specific bin details. B Across all synapses, the number of pLIMK gold particles was higher in the PSD bin of aged compared to young rats. C,D Similar age effects on PSD pLIMK were seen in non-perforated synapses, but not in perforated synapses. ***, p < 0.001. Graphs: circles, individual animals; line, group mean.

Two-way ANOVA analysis of quantitative PL PFC synaptic pLIMK distribution between young and aged animals revealed main effects of synaptic bin (F(5,40) = 113.5, p < 0.0001), age (F(1,8) = 20.81, p < 0.0001), and a significant interaction (F(5,40) = 4.783, p < 0.005). Bonferonni post hoc tests found a significant difference between young and aged animals in the number of gold particles located in the PSD per spine (p < 0.001), with no significant differences in the number of gold particles in any of the other synaptic bin compartments (Figure 3B). These data suggest that pLIMK molecules accumulate selectively at the PSD, but not in any other spine bin during aging.

We next asked whether the selective accumulation of pLIMK during aging depended on PSD morphology. ANOVA of PSD pLIMK in non-perforated synapses revealed main effects of synaptic bin (F(5,40) = 107.5, p < 0.0001), age (F(1,8) = 15.46, p < 0.0005), and a significant interaction (F(5,40) = 3.693, p < 0.01). Significant differences between young and aged animals were found in the number of gold particles located in the PSD per synapse (p < 0.001), with no differences in any other synaptic bin compartments (Figure 3C). In contrast, two-way ANOVA using data from perforated synapses found a main effect of synaptic bin (F(5,40) = 35.07, p < 0.0001), but not of age or an interaction. Post hoc tests failed to reveal any differences between the ages within any synaptic compartment (Figure 3D). Taken together, these analyses demonstrate age-related accumulations of pLIMK selectively in the PSD of non-perforated synapses, while pLIMK expression in perforated synapses remains unaltered by age.

3.4 Relationship between PSD pLIMK and PL PFC synapse morphology

Given the data suggesting a selective reduction of small, thin spines in monkey dorsolateral PFC and rat PL PFC during aging (Dumitriu et al., 2010, Bloss et al., 2011), we asked whether changes in PSD pLIMK labeling could be attributed to synapses of a particular size and therefore help explain synaptic vulnerability or resilience to aging. We used a cluster analysis to mathematically separate non-perforated synapses into 3 distinct clusters based on their PSD length. The use of the cluster analysis allows the separation of a heterogeneous population of synapses in an unbiased and objective approach as compared to arbitrarily defined bin sizes (see Methods). The results of the PSD length cluster analysis and sample sizes are defined in Table 1.

Two-way analysis of the synaptic density of each cluster across young and aged animals revealed a main effect of cluster (F(2,16) = 195.7, p < 0.0001), age (F(1,8) = 42.99, p < 0.0001), and a significant interaction (F(2,16) = 32.90, p < 0.0001). The density of smaller synapses in PSD cluster 1 (PSD length < 0.249 µm) were significantly decreased in the aged animals (p < 0.001), while densities of larger synapses in PSD cluster 2 (PSD length between 0.250 and 0.401 µm) and PSD cluster 3 (PSD length > 0.404 µm) synapses did not differ between the ages (Figure 4A).

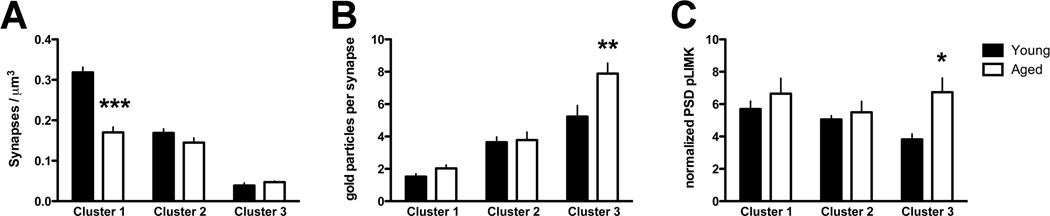

Figure 4. Higher number and density of pLIMK in the PSD of a subset of non-perforated synapses in the aged PFC.

A Cluster analysis was used to mathematically define classes of synapses based on PSD size; aging resulted in a ~50% decrease in synapse density in cluster 1 (smallest synapses). See Materials and Methods and Table 1 for details of the PSD cluster analysis. B,C The number (B) and density (C) of pLIMK immunogold particles within the PSD bin are plotted by age and synapse size (cluster). Exclusively in cluster 3 (largest) synapses, a significant age effect was observed in the number (B) and density (C) of PSD pLIMK. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. A significant cluster effect on normalized PSD pLIMK was present in the young group such that pLIMK density was significantly lower in the cluster 3 (largest) synapses compared to cluster 1 (smallest) synapses; no such cluster effect was present in aged animals (data not shown); see Results for details. Graphs represent mean ± SEM.

We next determined the abundance of PSD pLIMK by PSD cluster size, and found main effects of cluster (F(2,16) = 52.93, p < 0.0001), age (F(1,8) = 8.271, p < 0.01), and a significant interaction (F(2,16) = 4.27, p < 0.05). Bonferonni’s post hoc tests revealed age-related differences in the number of PSD gold particles between young and aged synapses only in the large synapses belonging to PSD cluster 3 (p < 0.01) (Figure 4B).

Lastly, we determined if aging synapses were enriched in pLIMK by normalizing the number of PSD gold particles to the sum total PSD length to derive the density of PSD pLIMK gold particles per µm of PSD (termed “normalized PSD pLIMK” in Figure 4C). Two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of age (F(1,8) = 7.1, p < 0.05) but not of cluster, and no significant interaction. Post hoc tests revealed a significantly higher PSD pLIMK in PSD cluster 3 in aged as compared to young animals (p < 0.05) (Figure 4C). Subsequently, we asked whether normalized PSD pLIMK was similar across spine size within each age group. In the young group, a one-way ANOVA showed a main effect of cluster (F(2,8)= 6.59, p < 0.05; data not shown), and Bonferonni’s post hoc tests revealed a significant difference in normalized PSD pLIMK between clusters 1 and 3 (p < 0.05). In contrast, ANOVA revealed no effect of cluster in aged animals (F(2,8) = 0.663, p > 0.5; data not shown). These data suggest that pLIMK density decreases with increasing synapse size in young animals, but remains similar across synapses of all sizes in aged animals. Since pLIMK is known to stabilize actin filaments, these data suggest that the higher levels of pLIMK within the PSD may be related to the selective maintenance of large, non-perforated spines during aging. However, these data also imply that this subpopulation of aging synapses has altered actin-related properties that may render them less capable of modification.

4. Discussion

The current study utilized postembedding immunogold electron microscopy to examine age-related changes in rat PL PFC synapses and the possible relationship of these alterations to the structural plasticity molecule pLIMK. The main findings are twofold; 1) aging selectively reduced the density of small, non-perforated synapses while the density of perforated synapses was unchanged, and 2) in the largest subset of PL PFC synapses, the number and density of PSD pLIMK is significantly higher in aged compared to young rats. Given that LIMK is associated with the stabilization of actin filaments (Arber et al., 1998), these data suggest that accumulation of pLIMK may explain the selective maintenance of large PL PFC spines during aging at the expense of their plasticity.

4.1 Age-related alterations of PL PFC axospinous synapses

The present study focused on the rat PL PFC cortex, a subdivision of the rat medial PFC that houses age-sensitive neuronal circuits required for working memory functions (Birrell and Brown, 2000, Barense et al., 2002). The present data are the first to demonstrate that aging results in a ~30% decrease of axospinous synapse density in rat PL PFC. These data are closely aligned with electron microscopic findings from aging monkey dorsolateral PFC, where a similar decrease in axospinous synapse density has been linked to cognitive dysfunction (Peters et al., 2008, Dumitriu et al., 2010).

Although we do not present volumetric data regarding age-related changes in the PL PFC here, previous studies of rat medial PFC have found either no change or a slight decrease of the volume of this structure in aging rats (Yates et al., 2008, Stranahan et al., 2011). Similarly, these same studies have provided evidence that there is no change in neuron number in this PFC subregion (Yates et al., 2008, Stranahan et al., 2011). Taken together, these results imply the changes in synapse density we report here are not likely to be driven by an age-related expansion of the rat PL PFC or a loss of PL PFC principle neurons. More likely, the changes seen here are the result of a gradual decline in dendritic spine density occurring over the lifetime of the rat, which may already be evident by middle-age (Bloss et al., 2011). Given the functional and anatomical differences of other subregions of rat PFC, which extends both dorsal and ventral to the PL, as well as ventrolaterally on the orbital surface, the statements made above regarding age-related changes in PL PFC synapse density should not be considered representative of the entire rat PFC and could potentially differ across these other PFC subregions.

The present data are consistent with light-level analyses of aging monkey dorsolateral and rat PL PFC dendritic spines (Duan et al., 2003, Dumitriu et al., 2010, Bloss et al., 2011), as well as data from Golgi-impregnated preparations from aging human PFC (Jacobs et al., 1997, Petanjek et al., 2011). One caveat to synapse analysis by light level microscopy, however, is the inability to discern synaptic ultrastructure. In contrast, EM is the only method that has sufficient resolution (~25 nm) to unambiguously identify synaptic contacts and allow accurate quantification of PSD morphology. The current study, then, provides the first data regarding these parameters within the context of aging PL PFC synapses. We find here that reductions in synapse density were driven entirely by non-perforated synapses; in contrast, the density of perforated synapses remained similar across the two ages. Evidence for a distinction between synapses with perforated and non-perforated PSDs can be found on both anatomical and functional levels; for example, hippocampal synapses with perforated PSDs are found in greater abundance in distal dendritic trees (Nicholson et al., 2006), and are known to express different complements of glutamate receptors (Desmond and Weinberg, 1998, Ganeshina et al., 2004). While similar data regarding perforated synapses in identified PL PFC microcircuitry have not been reported, it should be noted that loss of perforated synapses in hippocampus is strongly related to age-related long-term memory impairments in rodents and monkeys (Geinisman et al., 1986, Nicholson et al., 2004, Hara et al., 2011). Our finding that perforated synapse density is unchanged during aging in the PL PFC suggests perforated synapses provide a useful synaptic subclass to investigate vulnerability and resilience to aging across these two cognitive circuits.

The second important finding regarding PSD morphology and aging is that the density of a discrete subpopulation of synapses with small PSDs (i.e, smaller than ~250 nm) are decreased with aging while the density of those with larger PSDs appear to be unchanged. When we utilized an objective and mathematically unbiased cluster analysis, the reduction in density of small synapses approached 50%. These data extend recent reports demonstrating a similar substantial yet selective decline in the density of small, thin dendritic spines in the aged PFC of rodents and monkeys (Dumitriu et al., 2010, Bloss et al., 2011). Based on empirical and computational modeling data, Arnsten and colleagues (2010) have proposed that biophysical and biochemical properties of thin spines within PFC circuits, in particular the presence of elongated spine necks and frequent expression of several types of catecholamine receptors, makes thin spines essential for optimal performance on PFC-dependent working memory tasks (Arnsten et al., 2010). In contrast to the reduction of small synapses our cluster analysis data suggest larger synapses are unchanged during aging, which is consistent with in vivo and in vitro imaging data demonstrating an increased stability of larger spine synapses over time (Holtmaat et al., 2005, Yasumatsu et al., 2008).

4.2 Age-related alterations of PL PFC synaptic pLIMK

Given the broad evidence that synaptic plasticity mechanisms are compromised with aging (Burke and Barnes, 2006) and more recent evidence demonstrating that LIMK plays a prominent role in controlling synapse ultrastructure and synaptic plasticity (Meng et al., 2002), we hypothesized that the subcellular distribution or number of pLIMK molecules would be altered with age in PL PFC synapses. The localization of LIMK is dependent on its PDZ domain (Yang and Mizuno, 1999), a common motif found in synaptic scaffolding proteins at the PSD of excitatory synapses. We report here that the majority of pLIMK is localized to the PSD in PL PFC synapses, which is in agreement with previous findings from postembedding immunogold analysis of hippocampal CA1 synapses (Yildirim et al., 2008). Furthermore, this observation is consistent with the fact that the LIMK substrate proteins actin and cofilin are known to concentrate within the spine PSD (Cohen et al., 1985, Racz and Weinberg, 2006).

While the predominant localization of pLIMK to the PSD was not altered by age, we found that aging PL PFC synapses contain approximately 50% more pLIMK within the PSD (the approximate 30% increase of pLIMK within the spine head core of aged synapses failed to reach statistical significance; see Figures 3B and 3C). The age-related increase in pLIMK in the PSD was restricted to a subset of large non-perforated synapses that were resistant to age-related decline in density. Interestingly, perforated synapse density was maintained during aging in the absence of altered pLIMK expression, suggesting stability of perforated synapses may be mediated by other factors (e.g., recruitment of other actin-stabilizing proteins, adhesion molecules, etc). In aged compared to young rats, pLIMK immunogold labeling was significantly higher within the PSDs of the largest subset of non-perforated PL PFC synapses even when controlling for total PSD size; thus, our data suggest that the accumulation of pLIMK in these synapses during aging is not a result of simply scaling along with PSD size (or a shift in the size of synapses assigned to this cluster). As neither pLIMK gold particle number nor distribution was distinctly different in the synaptic subclass most vulnerable to decrease in density during aging (data not shown), our data also suggest the selective accumulation of pLIMK in large synapses during aging may relate to synapse stability and maintenance rather than vulnerability. It should be noted, however, that other proteins that stabilize (e.g., cortactin) or de-stabilize (e.g., gelsolin) actin filaments might also play a prominent role in synaptic morphological changes in the aging PL PFC.

It is plausible that alterations of the pLIMK pathway seen during aging in these synapses may impair PFC synaptic plasticity by several mechanisms. We suspect one mechanism by which increased pLIMK might change synapse plasticity is by altering the capacity for synaptic structural remodeling, including both actin-dependent spine expansion and shrinkage. The hypothesis that LIMK is a major regulator of synapse structure is consistent with data from LIMK1 mutant mice, where deletion of LIMK1 resulted in altered spine and PSD size (Meng et al., 2002). A second likely mechanism by which altered patterns of synaptic pLIMK might contribute to reduced plasticity in aging synapses is by controlling activity-dependent trafficking of molecules within the PSD. It has been shown recently in vitro that activity of the LIMK substrate cofilin is required for rapid surface expression of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunit GluA1 (Gu et al., 2010). Since cofilin is the only known target of LIMKs and is inhibited by pLIMK, we hypothesize that increased pLIMK in aging synapses might impair the activity-dependent trafficking of GluA1 and potentially other molecules at the PSD.

From these data, we predict upstream signaling pathways that regulate LIMK, including Rhofamily GTPases and their effector molecules PAK and ROCK, could be tonically activated in aging PFC synapses. An equally plausible alternative is that aging disrupts the ability to dephosphorylate pLIMK in PL PFC synapses through reduced expression or activity of the LIMK (and cofilin) phosphatase slingshot (Soosairajah et al., 2005). The data reported here may lend stronger support to the latter scenario, as PSD pLIMK density decreased as synapse size increased in young, but not aged animals. To our knowledge, neither possibility has been explored in any region of the aging brain, but could potentially provide some critical data regarding age-related impairments in synaptic structural and functional plasticity.

Taken together, the present study provides the first ultrastructural data regarding synaptic aging in the rat PL PFC. Furthermore, we provide the first data to demonstrate that synaptic expression of pLIMK, an actin-binding molecule that has been implicated in structural and functional synaptic plasticity, is altered during aging. Given that rapid and continuous plasticity of synaptic connectivity is thought to promote PFC-mediated executive functioning (Elston, 2000, Arnsten et al., 2010), our data support a model in which both synapse loss and molecular changes at the remaining synapses may contribute to age-related deficits in working memory capacity. Interestingly, while we find here that pLIMK accumulates in aging PL PFC synapses, opposite patterns have been observed for CA1 synapses (Yildirim et al., 2008), which strengthens the notion that the neurobiological mechanisms of aging may differ considerably between the hippocampus and PL PFC (Baxter, 2003). Future studies should seek to clarify the relationship of pLIMK to hippocampal and/or PFC functional decline during aging, particularly between impaired and unimpaired subjects. Given the link between increased neocortical pLIMK in humans with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (Heredia et al., 2006), studies focused on pathways both up- and downstream of LIMK may considerably enhance our understanding of the neurobiological mediators of cognitive aging and disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Patrick Hof and Bridget Wicinski for expert advice and assistance. This work is supported by NIH grants AG034794 to E.B.B., MH58911 to B.S.M and J.H.M., and AG006647 to J.H.M.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement. All authors have read the manuscript and report no actual or potential conflict of interest. The authors verify that appropriate approvals and procedures were used for the animal subjects in this study.

Contributor Information

Erik B. Bloss, Email: erik.bloss@mssm.edu.

Rishi Puri, Email: rishi.puri@mssm.edu.

Frank Yuk, Email: frank.yuk@mssm.edu.

Michael Punsoni, Email: mipunsoni@yahoo.com.

Yuko Hara, Email: yuko.hara@mssm.edu.

William G. Janssen, Email: bill.Janssen@mssm.edu.

Bruce S. McEwen, Email: mcewen@mail.rockefeller.edu.

John H. Morrison, Email: john.morrison@mssm.edu.

References

- Adams MM, Shah RA, Janssen WG, Morrison JH. Different modes of hippocampal plasticity in response to estrogen in young and aged female rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8071–8076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141215898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altun M, Bergman E, Edstrom E, Johnson H, Ulfhake B. Behavioral impairments of the aging rat. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:911–923. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber S, Barbayannis FA, Hanser H, Schneider C, Stanyon CA, Bernard O, Caroni P. Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature. 1998;393:805–809. doi: 10.1038/31729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Paspalas CD, Gamo NJ, Yang Y, Wang M. Dynamic Network Connectivity: A new form of neuroplasticity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barense MD, Fox MT, Baxter MG. Aged rats are impaired on an attentional set-shifting task sensitive to medial frontal cortex damage in young rats. Learn Mem. 2002;9:191–201. doi: 10.1101/lm.48602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter MG. Age-related memory impairment. Is the cure worse than the disease? Neuron. 2003;40:669–670. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JM, Brown VJ. Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4320–4324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04320.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss EB, Janssen WG, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Interactive effects of stress and aging on structural plasticity in the prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6726–6731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0759-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss EB, Janssen WG, Ohm DT, Yuk FJ, Wadsworth S, Saardi KM, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Evidence for reduced experience-dependent dendritic spine plasticity in the aging prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7831–7839. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0839-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Barnes CA. Neural plasticity in the ageing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:30–40. doi: 10.1038/nrn1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RS, Chung SK, Pfaff DW. Immunocytochemical localization of actin in dendritic spines of the cerebral cortex using colloidal gold as a probe. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1985;5:271–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00711012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft DR, Olson MF. The Rho GTPase effector ROCK regulates cyclin A, cyclin D1, and p27Kip1 levels by distinct mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4612–4627. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02061-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot DM, Bierman EP. A critical evaluation of methods for estimating the numerical density of synapses. J Neurosci Methods. 1986;18:79–101. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(86)90113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond NL, Weinberg RJ. Enhanced expression of AMPA receptor protein at perforated axospinous synapses. Neuroreport. 1998;9:857–860. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199803300-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Remedios CG, Chhabra D, Kekic M, Dedova IV, Tsubakihara M, Berry DA, Nosworthy NJ. Actin binding proteins: regulation of cytoskeletal microfilaments. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:433–473. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H, Wearne SL, Rocher AB, Macedo A, Morrison JH, Hof PR. Age-related dendritic and spine changes in corticocortically projecting neurons in macaque monkeys. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:950–961. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.9.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitriu D, Hao J, Hara Y, Kaufmann J, Janssen WG, Lou W, Rapp PR, Morrison JH. Selective changes in thin spine density and morphology in monkey prefrontal cortex correlate with aging-related cognitive impairment. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7507–7515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6410-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston GN. Pyramidal cells of the frontal lobe: all the more spinous to think with. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-j0002.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukazawa Y, Saitoh Y, Ozawa F, Ohta Y, Mizuno K, Inokuchi K. Hippocampal LTP is accompanied by enhanced F-actin content within the dendritic spine that is essential for late LTP maintenance in vivo. Neuron. 2003;38:447–460. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamell C, Osses N, Bartrons R, Ruckle T, Camps M, Rosa JL, Ventura F. BMP2 induction of actin cytoskeleton reorganization and cell migration requires PI3-kinase and Cdc42 activity. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3960–3970. doi: 10.1242/jcs.031286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganeshina O, Berry RW, Petralia RS, Nicholson DA, Geinisman Y. Differences in the expression of AMPA and NMDA receptors between axospinous perforated and nonperforated synapses are related to the configuration and size of postsynaptic densities. J Comp Neurol. 2004;468:86–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.10950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geinisman Y, de Toledo-Morrell L, Morrell F. Loss of perforated synapses in the dentate gyrus: morphological substrate of memory deficit in aged rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:3027–3031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Lee CW, Fan Y, Komlos D, Tang X, Sun C, Yu K, Hartzell HC, Chen G, Bamburg JR, Zheng JQ. ADF/cofilin-mediated actin dynamics regulate AMPA receptor trafficking during synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1208–1215. doi: 10.1038/nn.2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Park CS, Janssen WG, Punsoni M, Rapp PR, Morrison JH. Synaptic characteristics of dentate gyrus axonal boutons and their relationships with aging, menopause, and memory in female rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7737–7744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0822-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heredia L, Helguera P, de Olmos S, Kedikian G, Sola Vigo F, LaFerla F, Staufenbiel M, de Olmos J, Busciglio J, Caceres A, Lorenzo A. Phosphorylation of actin-depolymerizing factor/cofilin by LIM-kinase mediates amyloid beta-induced degeneration: a potential mechanism of neuronal dystrophy in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6533–6542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5567-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat AJ, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L, Shepherd GM, Zhang X, Knott GW, Svoboda K. Transient and persistent dendritic spines in the neocortex in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honkura N, Matsuzaki M, Noguchi J, Ellis-Davies GC, Kasai H. The subspine organization of actin fibers regulates the structure and plasticity of dendritic spines. Neuron. 2008;57:719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh SH, Ferraro GB, Fournier AE. Myelin-associated inhibitors regulate cofilin phosphorylation and neuronal inhibition through LIM kinase and Slingshot phosphatase. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1006–1015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2806-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs B, Driscoll L, Schall M. Life-span dendritic and spine changes in areas 10 and 18 of human cortex: a quantitative Golgi study. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:661–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen WG, Vissavajjhala P, Andrews G, Moran T, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Cellular and synaptic distribution of NR2A and NR2B in macaque monkey and rat hippocampus as visualized with subunit-specific monoclonal antibodies. Exp Neurol. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S28–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DA, Lessard AA, Chan J, Colago EE, Zhou Y, Schlussman SD, Kreek MJ, Pickel VM. Region-specific changes in the subcellular distribution of AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit in the rat ventral tegmental area after acute or chronic morphine administration. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9670–9681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2151-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus A. Actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Science. 2000;290:754–758. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Zhang Y, Tregoubov V, Janus C, Cruz L, Jackson M, Lu WY, MacDonald JF, Wang JY, Falls DL, Jia Z. Abnormal spine morphology and enhanced LTP in LIMK-1 knockout mice. Neuron. 2002;35:121–133. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Mervis CB, Berman KF. Neural mechanisms in Williams syndrome: a unique window to genetic influences on cognition and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:380–393. doi: 10.1038/nrn1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra UK, Sharma T, Pizzo SV. Ligation of cell surface-associated glucose-regulated protein 78 by receptor-recognized forms of alpha 2-macroglobulin: activation of p21-activated protein kinase-2-dependent signaling in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;175:2525–2533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson DA, Trana R, Katz Y, Kath WL, Spruston N, Geinisman Y. Distance-dependent differences in synapse number and AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 2006;50:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson DA, Yoshida R, Berry RW, Gallagher M, Geinisman Y. Reduction in size of perforated postsynaptic densities in hippocampal axospinous synapses and age-related spatial learning impairments. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7648–7653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1725-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Nagai T, Miyawaki A, Hayashi Y. Rapid and persistent modulation of actin dynamics regulates postsynaptic reorganization underlying bidirectional plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1104–1112. doi: 10.1038/nn1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in streotaxic coordinates. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petanjek Z, Judas M, Simic G, Rasin MR, Uylings HB, Rakic P, Kostovic I. Extraordinary neoteny of synaptic spines in the human prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13281–13286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105108108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Morrison JH, Rosene DL, Hyman BT. Feature article: are neurons lost from the primate cerebral cortex during normal aging? Cereb Cortex. 1998;8:295–300. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.4.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Sethares C, Luebke JI. Synapses are lost during aging in the primate prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2008;152:970–981. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racz B, Weinberg RJ. Spatial organization of cofilin in dendritic spines. Neuroscience. 2006;138:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soosairajah J, Maiti S, Wiggan O, Sarmiere P, Moussi N, Sarcevic B, Sampath R, Bamburg JR, Bernard O. Interplay between components of a novel LIM kinase-slingshot phosphatase complex regulates cofilin. EMBO J. 2005;24:473–486. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JL, Waters EM, Milner TA, McEwen BS. Estrous cycle regulates activation of hippocampal Akt, LIM kinase, and neurotrophin receptors in C57BL/6 mice. Neuroscience. 2008;155:1106–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterio DC. The unbiased estimation of number and sizes of arbitrary particles using the disector. J Microsc. 1984;134:127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1984.tb02501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranahan AM, Jiam NT, Stocker AM, Gallagher M. Aging reduces total neuron number in the dorsal component of the rodent prefrontal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cne.22790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassabehji M, Metcalfe K, Fergusson WD, Carette MJ, Dore JK, Donnai D, Read AP, Proschel C, Gutowski NJ, Mao X, Sheer D. LIM-kinase deleted in Williams syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;13:272–273. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigges J, Herndon JG, Rosene DL. Preservation into old age of synaptic number and size in the supragranular layer of the dentate gyrus in rhesus monkeys. Acta Anat (Basel) 1996;157:63–72. doi: 10.1159/000147867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang AC, Hara Y, Janssen WG, Rapp PR, Morrison JH. Synaptic estrogen receptor-alpha levels in prefrontal cortex in female rhesus monkeys and their correlation with cognitive performance. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12770–12776. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3192-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Higuchi O, Ohashi K, Nagata K, Wada A, Kangawa K, Nishida E, Mizuno K. Cofilin phosphorylation by LIM-kinase 1 and its role in Rac-mediated actin reorganization. Nature. 1998;393:809–812. doi: 10.1038/31735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Mizuno K. Nuclear export of LIM-kinase 1, mediated by two leucine-rich nuclear-export signals within the PDZ domain. Biochem J. 1999;338(Pt 3):793–798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasumatsu N, Matsuzaki M, Miyazaki T, Noguchi J, Kasai H. Principles of long-term dynamics of dendritic spines. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13592–13608. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0603-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates MA, Markham JA, Anderson SE, Morris JR, Juraska JM. Regional variability in agerelated loss of neurons from the primary visual cortex and medial prefrontal cortex of male and female rats. Brain Res. 2008;1218:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim M, Janssen WG, Tabori NE, Adams MM, Yuen GS, Akama KT, McEwen BS, Milner TA, Morrison JH. Estrogen and aging affect synaptic distribution of phosphorylated LIM kinase (pLIMK) in CA1 region of female rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2008;152:360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen EY, Liu W, Kafri T, van Praag H, Yan Z. Regulation of AMPA receptor channels and synaptic plasticity by cofilin phosphatase Slingshot in cortical neurons. J Physiol. 2010;588:2361–2371. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.186353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]