Abstract

Objectives

Biliary atresia (BA) frequently results in portal hypertension (PHT), complications of which lead to significant morbidity and mortality. The Childhood Liver Disease Research and Education Network (ChiLDREN) was utilized to perform a cross-sectional multi-centered analysis of PHT in children with BA.

Methods

BA subjects receiving medical management at a ChiLDREN site were enrolled. A priori, clinically evident PHT was defined as “definite” when there was either 1) history of a complication of PHT or 2) clinical findings consistent with PHT (both splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia). PHT was denoted as “possible” if one of the findings was present in the absence of a complication, while PHT was “absent” if none of the criteria were met.

Results

163 subjects were enrolled between May 2006 and December 2009. At baseline, definite PHT was present in 49%, possible in 17% and absent in 34% of subjects. Demographics, growth and anthropometrics were similar amongst the 3 PHT categories. ALT, GGTP, and sodium levels were similar, while there were significant differences in AST, AST/ALT, albumin, total bilirubin, PT, WBC, platelet count and AST/platelet between definite and absent PHT. Thirty-four percent of those with definite PHT had either PT > 15s or albumin < 3 g/L.

Conclusions

Clinically definable PHT is present in two thirds of North American long-term BA survivors with their native livers. The presence of PHT is associated with measures of hepatic injury and dysfunction, although in this selected cohort the degree of hepatic dysfunction is relatively mild and growth is preserved.

Keywords: varices, pediatric, ascites, hepatopulmonary syndrome, hypersplenism

Portal hypertension (PHT) is a common consequence of biliary atresia (BA) and can lead to significant morbidity and mortality (1). Elevated portal pressure has been demonstrated as early as the time of hepatoportoenterostomy (2). The rate of development of complications of PHT is dependent in part upon whether bile flow is restored, with relatively rapid progression in infants with poor bile flow whose serum bilirubin levels remain elevated (i.e. “failed Kasai”) (3, 4). Despite good bile flow as demonstrated by normalization of serum bilirubin levels, the majority of children with BA still develop biliary cirrhosis with typical complications of PHT. Most published analyses of PHT are single center studies and focus on either the development of, or intervention for, clinical complications of PHT (5–12). Some are part of general surveys of BA and not focused on issues related to PHT. Many reports emanate from time periods when the development of complications of PHT was an indication for proceeding with liver transplantation. In the current era, many centers proceed with liver transplantation in infants and toddlers with BA who have evidence of poor bile flow after hepatoportoenterostomy, which is in effect pre-emptive for complications of PHT (1). Thus earlier reports may not necessarily be representative of the current clinical spectrum of PHT in BA.

Unlike the practice in adults, portal pressures are not typically measured in children. Moreover, hepatic venous pressure gradients, when performed in BA, have the potential to underestimate actual portal pressure, both because of the primarily presinusoidal nature of the lesion in BA, but also because of the unexpected finding of intrahepatic venovenous collaterals (13). Defining PHT simply by the presence or absence of complications of PHT would underestimate its prevalence, since elevated portal pressure preceeds the development of both varices and ascites. In addition, reliance on endoscopic findings of portal hypertension depends upon surveillance endoscopy in at-risk children, which is not used by many clinicians in North America (14–16). A broader clinical definition of PHT would be of great value in pediatric hepatology given the invasive nature associated with direct measurement of portal pressure in children, as well as problems associated with and the limited availability of direct or indirect measurement of portal pressure in children.

The purpose of the present study was to carefully examine a large well-characterized multi-center cross-sectional cohort of children with BA for the presence of PHT. This cohort was designed to reflect what one might encounter in the follow-up of children who survived with their native liver. The analysis used readily available non-invasive and practical clinical and laboratory objective measurable criteria. Both the nature and type of complications of PHT as well as laboratory correlates of PHT were investigated. In addition, the analysis was intended to set a baseline framework for potential future clinical investigations of PHT in children with BA (16)

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Study Subjects

Subjects for this investigation were participants in the Biliary Atresia Study of Infants and Children (BASIC – study ID: NCT00061828) conducted as part of the Childhood Liver Disease Research and Education Network (ChiLDREN), an NIDDK/NIH funded research consortium. ChiLDREN is conducting several studies of BA including BASIC. Infants diagnosed with neonatal cholestasis who were subsequently diagnosed with BA may be enrolled in a separate prospective study, PROBE (Prospective Database of Infants with Cholestasis, study ID: NCT 00061828) and are therefore not included in this analysis, but will be the subject of a separate prospective analysis. During the time frame of this analysis, 10 of the current 15 ChiLDREN centers, were participating. BASIC is a prospective longitudinal cohort study of children and young adults with BA. A subset of the data elements collected in BASIC was designed to examine medical history, physical examination findings, and laboratory data relevant to PHT. Data were collected by clinical investigators with expertise in Pediatric Hepatology and dedicated clinical research coordinators. This analysis was confined to data collected at the time of enrollment into BASIC and did not examine prospective longitudinal follow up. At enrollment, past medical history was collected with a detailed review of events occurring during the previous 12 months. Laboratory data collected at the time of enrollment included clinically indicated testing ordered by the clinician caring for the study subject. There were no per protocol laboratory investigations performed as part of the study. Since surveillance endoscopy was not routinely practiced at many of the centers, the use of endoscopic data would have added considerable bias; thus endoscopy findings were not assessed in this analysis.

For the purpose of this investigation, an a priori operational definition of PHT was developed. Study subjects were classified as definite, possible or absent relative to the presence of features of PHT. A priori, clinically evident PHT was defined as “definite” when there was either 1) a history of a complication of PHT (esophageal or gastric variceal (EV) bleed, ascites, or hepatopulmonary syndrome) or 2) clinical findings consistent with PHT (both splenomegaly [spleen palpable > 2 cm below the costal margin] and thrombocytopenia [platelet count < 150,000/ml]). Spleen excursion below the costal margin was chosen as a parameter that was felt to be clinically significant and reproducible in the hands of an experienced clinician. Spleen size was not consistently assessed at the ChiLDREN centers by routine sonography and thus was not be used in this definition. The platelet count cut-off reflects an abnormal value, one that could be a manifestation of hypersplenism. PHT was denoted as “possible” if only one of the two clinical findings was present in the absence of a complication, while PHT was “absent” if none of the criteria were met.

Inclusion criteria for the present analysis included enrollment in BASIC and continuous medical care for BA at the ChiLDREN site. The diagnosis of BA was confirmed by review of pathology reports, imaging studies and/or operative reports. Subjects were excluded if they had undergone liver transplantation or were referred to the ChiLDREN site specifically for evaluation for liver transplantation. The latter exclusion was meant to reduce the bias of assessing children with more severe disease, as would be expected for liver transplant candidates. Thus study subjects had to have been medically followed at the ChiLDREN site from the time of their hepatoportoenterostomy or had their care transferred to the ChiLDREN site for the purpose of medical follow-up and not simply for evaluation for liver transplantation. Study subjects who received continuous medical care at the ChiLDREN study site who were liver transplant candidates were eligible for this analysis. Subjects who had undergone splenectomy or those with polysplenia or asplenia were excluded as this status might impact on the proposed operational definition of PHT. Subjects were excluded from analysis if the status relative to PHT could not be definitively determined due to an absence of clinical data (e.g. platelet count or spleen size).

Informed consent in writing was obtained from parents or guardians with assent from the subject when age appropriate. Study protocols were approved at each center by the institutional review committee.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations for continuous variables; counts and percentages for categorical variables) were reported for the three (definite, possible and absent) PHT groups. Continuous variables were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance model consisting of PHT group; differences among the means were considered significant at the α = 0.05 level. Categorical variables were analyzed with Fisher’s Exact Test; and differences considered significant at the α = 0.05 level.

The presence or absence of a history of complications (ascites and/or EV bleed and/or HPS) as a function of splenomegaly and/or thrombocytopenia at enrollment was analyzed with a logistic regression model. The model consisted of splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia as dichotomous (present/absent) predictor variables and their interaction. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the probability of a complication were generated for all four groups. Using the “splenomegaly absent, thrombocytopenia absent” group as the reference, point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the relative risk of complications for the remaining three groups were determined. Two-sided p-values for H0: relative risk = 1 were also generated (17).

All analyses were performed in SAS 9.1 (18).

RESULTS

Study Subjects

A total of 211 BASIC BA subjects with their native liver were enrolled between May 2006 and Dec 2009. Eighteen subjects were excluded because they were referred to the ChiLDREN site primarily for the purpose of liver transplant evaluation (9 with definite PHT, 2 with possible PHT and 5 with absent PHT). Seven subjects were excluded due to polysplenia, which may preclude measurement of spleen size as a criteria of PHT – none had a history of a complication of PHT. Six of seven of these subjects would have been classified as absent PHT, one subject with polysplenia had splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia. There were no subjects reported to have either asplenia or had undergone surgical splenectomy. Twenty-three subjects were excluded due to incomplete clinical data that prevented precise classification of PHT. Thus this analysis is based on the remaining 163 subjects who were followed for routine clinical care of their BA at one of the 10 ChiLDREN centers.

Clinical Characteristics of Subjects

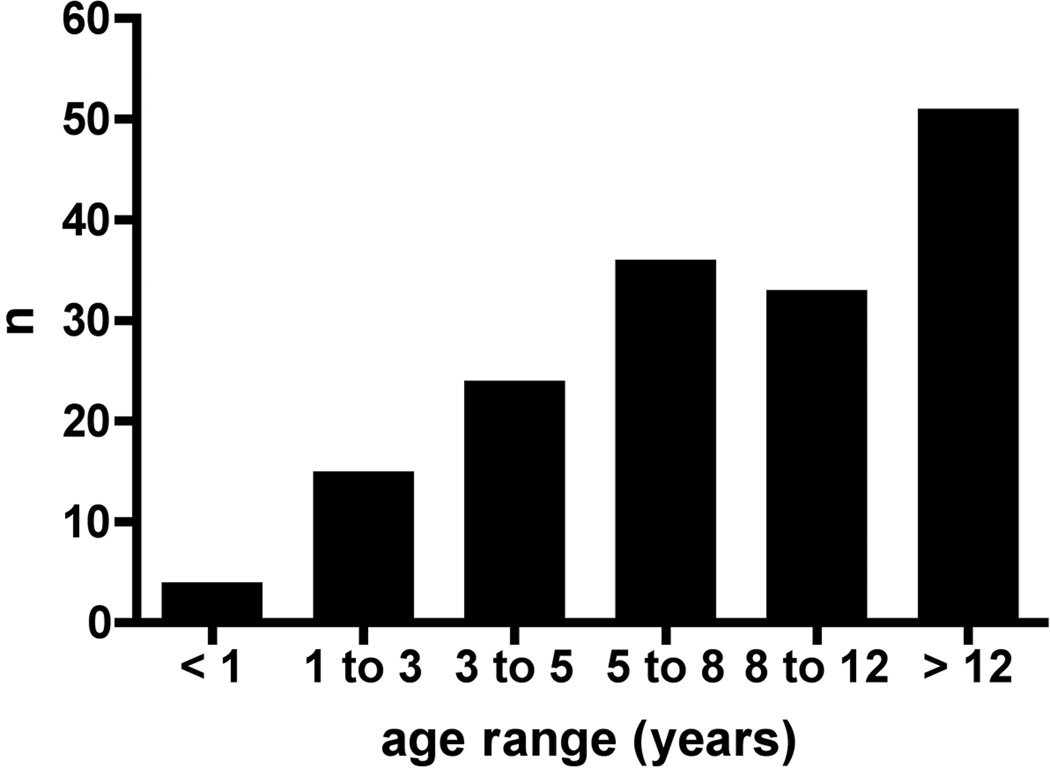

Subject ages at enrollment ranged from 1 to 25 years with a mean of 9.2 ± 5.6 years (± SD). The distribution of ages at enrollment is shown in Figure 1. 56% of subjects were female, 13% Hispanic, 75% white, 18% black and 7% Asian. Using the clinical definition of PHT developed for this study, PHT was definite in 80 (49%) and absent in 56 (34%); 27 (17%) had possible PHT defined by either splenomegaly or thrombocytopenia without a history of any of the defined complications of PHT. There were no differences in the mean age at hepatoportoenterostomy, age at enrollment, gender, ethnicity or race among the three groups (Table 1). The frequency of previous episodes of cholangitis was not different in the three PHT groups (Table 1). Nonspecific β-blocker therapy was employed at the time of enrollment in the study in 8 out of 163 study subjects (definite PHT, n=7 and possible PHT, n = 1).

Figure 1.

Age distribution at enrollment. The number of BA subjects of the cohort of 163 in each age range is indicated in this bar graph.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and growth parameters of subjects with BA

| Parameter | PHT definite | PHT possible | PHT absent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 9.1 ± 6.0 (80)* | 8.7 ± 5.1 (27) | 9.7 ± 5.2 (56) |

| Age at HPE, mo | 1.9 ± 0.8 (74) | 2.1 ± 2.7 (26) | 1.9 ± 0.9 (56) |

| Cholangitis | |||

| 0 episodes | 39% | 29% | 33% |

| 1 episode | 16% | 31% | 26% |

| 2–5 episodes | 36% | 36% | 33% |

| >5 episodes | 9% | 5% | 7% |

| Weight† | 0.08 ± 1.24 (80) | 0.05 ± 1.71 (26) | 0.45 ± 0.94 (56) |

| Height‡ | −0.22 ± 1.29 (80) | −0.60 ± 1.73 (25) | 0.15 ± 1.06 (56) |

| BMI | 0.42 ± 1.16 (70) | 0.82 ± 1.12 (22) | 0.53 ± 0.87 (53) |

| Mid arm circumference | 0.13 ± 2.31 (40) | −0.55 ± 2.21 (14) | −0.09 ± 1.61 (31) |

| Triceps skin-fold thickness | −0.12 ± 0.93 (39) | −0.07 ± 1.53 (14) | 0.39 ± 1.44 (31) |

| Subscapular skin fold | −0.08 ± 0.65 (32) | 0.11 ± 0.85 (9) | 0.05 ± 0.77 (23) |

BA = biliary atresia; BMI = body mass index; HPE = hepatoportoenterostomy; PHT = portal hypertension.

Mean ± standard deviation, number in parenthesis indicates number of subjects with measurement of interest.

Weight, height, BMI, arm circumference, triceps skin fold, and subscapular skin fold all expressed as z score for age. No significant differences for any of the comparisons were noted. Note BMI z scores not available at age <2 years.

PHT absent vs PHT possible, significant at α = 0.05.

Defining Manifestations of Portal Hypertension

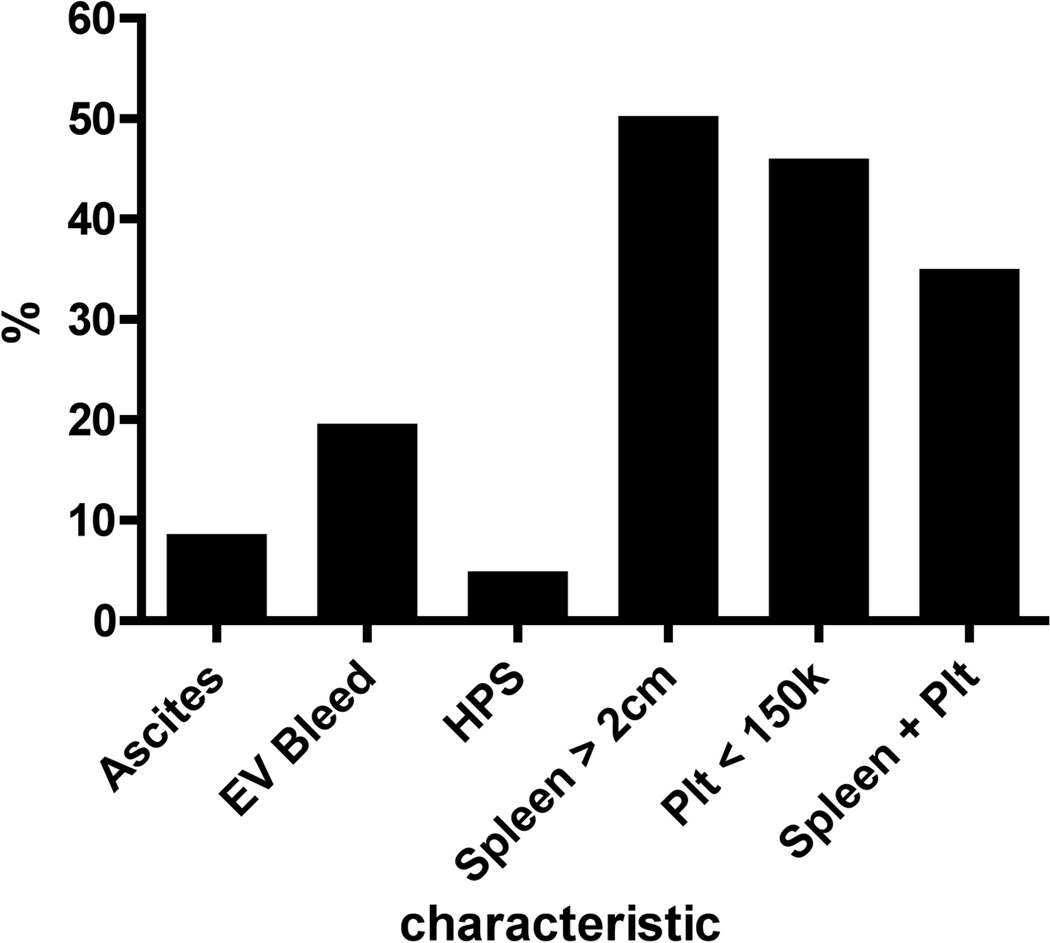

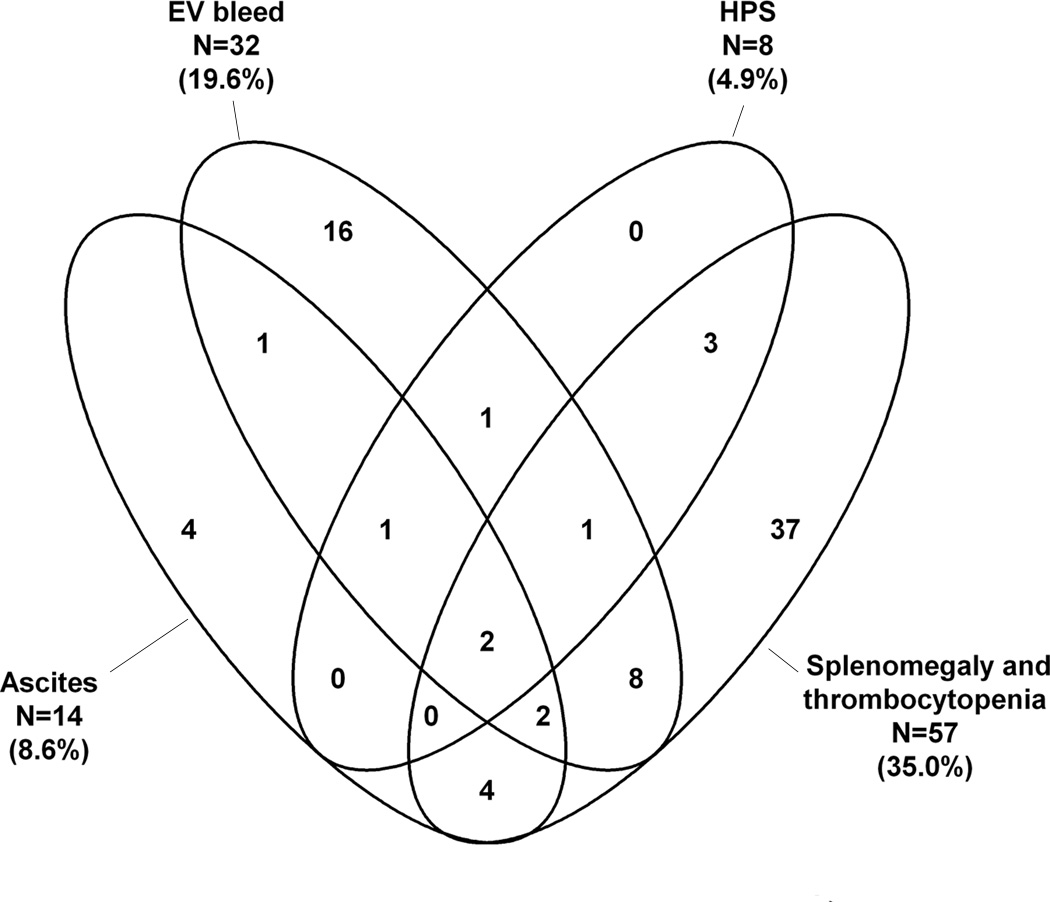

Forty-three of the 163 subjects had a history of a complication of PHT, while 37 subjects met the definite PHT criteria solely based on spleen size and platelet count (Figure 2A). Some study subjects had experienced multiple complications of PHT. Of the 43 subjects with a history of complications the most common event was EV bleed (n=32); less common were ascites (n=14) and hepatopulmonary syndrome (n=8) (Figure 2A). Of the 32 with EV bleeding, 7 had their first bleed between birth and 2 years, 7 between 2 and 5 years, 11 between 6 and 10 years and 7 after the age of 10 years. Twenty of the 32 had only one episode of bleeding. Twelve children had at least 5 years follow up after an episode of EV bleeding; 6 had no further episodes, 4 had 1 to 5 episodes, while 2 had more than 5 episodes. The interrelationship of the defining manifestations of PHT is seen in Figure 2B. The overlap of the manifestations is varied and complex with no specific pattern.

Figure 2.

A: Presence of clinical characteristics or history of complications of PHT at enrollment. The percentage of the BA subjects who reported ascites, esophageal variceal bleeding (EV Bleed), hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS), splenomegaly [spleen tip > 2 cm below the costal margin], thrombocytopenia [Platelet count (plt) < 150k] or both (Spleen + Plt) are noted. Subjects could have more than one characteristic or complication so that the total is greater than 100%.

B: Venn diagram of the factors determining presence of Definite PHT. The factor associated with definite PHT is represented by each ellipse and is described by the text next to the ellipse. The interrelationship of the features is indicated by the overlap of the ellipses and the number with the overlapping sections. For example, following the left-most ellipse of Ascites, only 4 of the 14 reported ascites alone, while 1 each reported ascites+ EV bleed and ascites + HPS + EV bleed, while none of the 8 subjects with HPS had HPS + ascites. In 56 subjects PHT was absent and in 27 it was possible (not shown). Sizes of the ellipses do not correlate with the number of subjects. EV = esophagogastric variceal hemorrhage; HPS = hepatopulmonary syndrome.

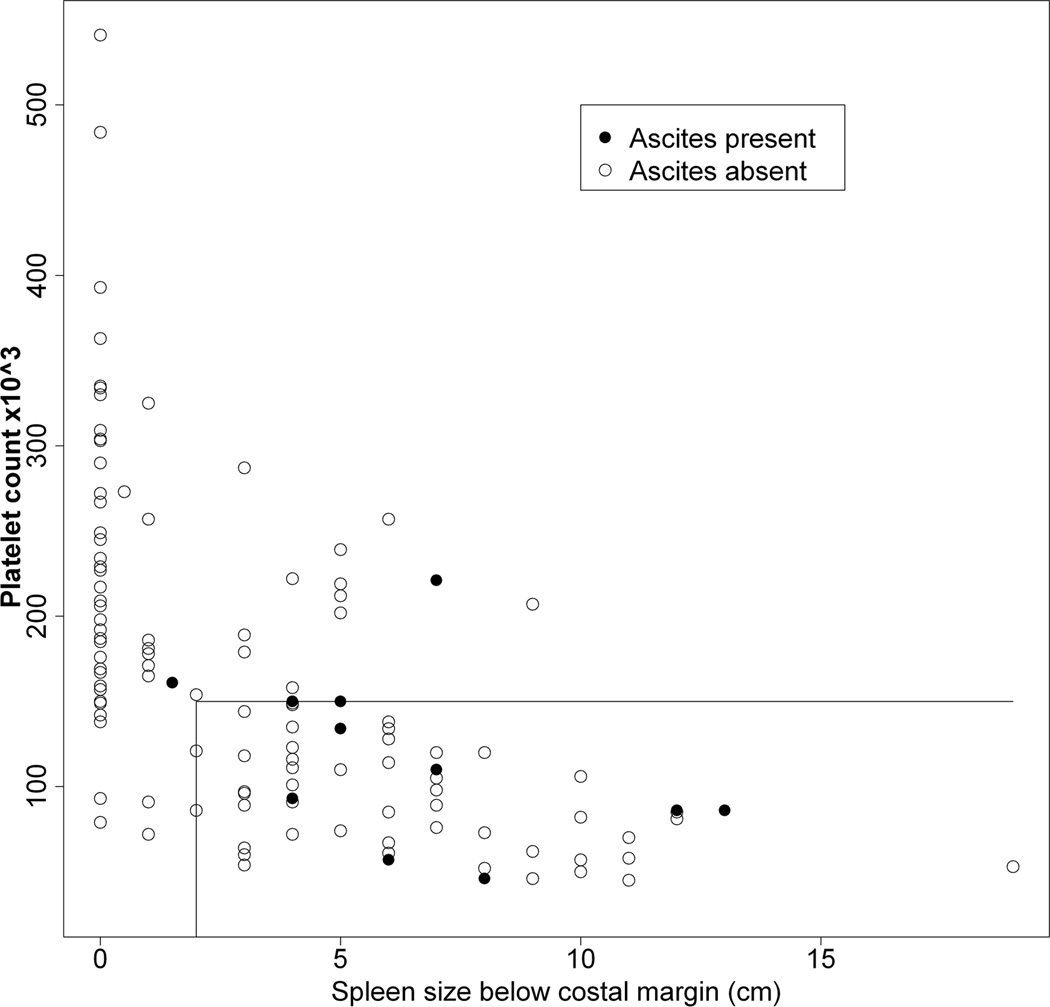

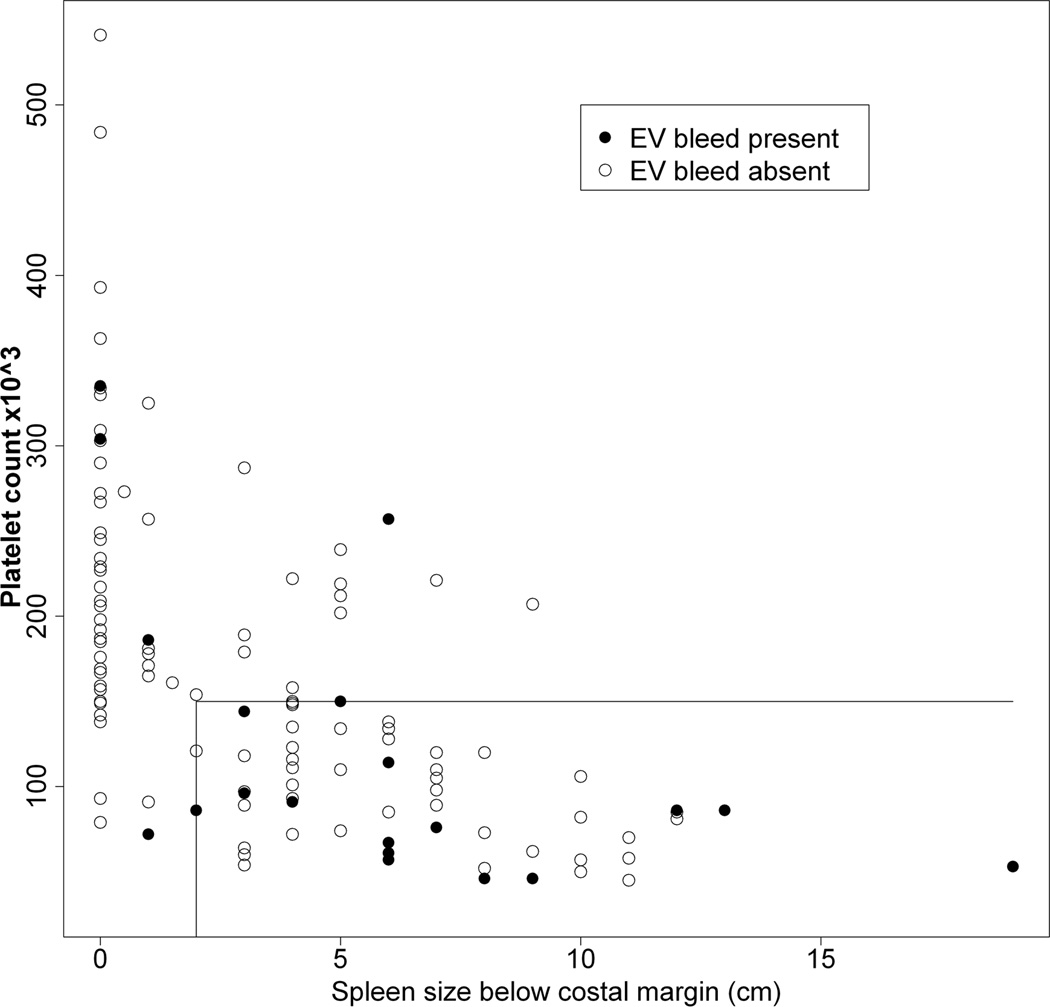

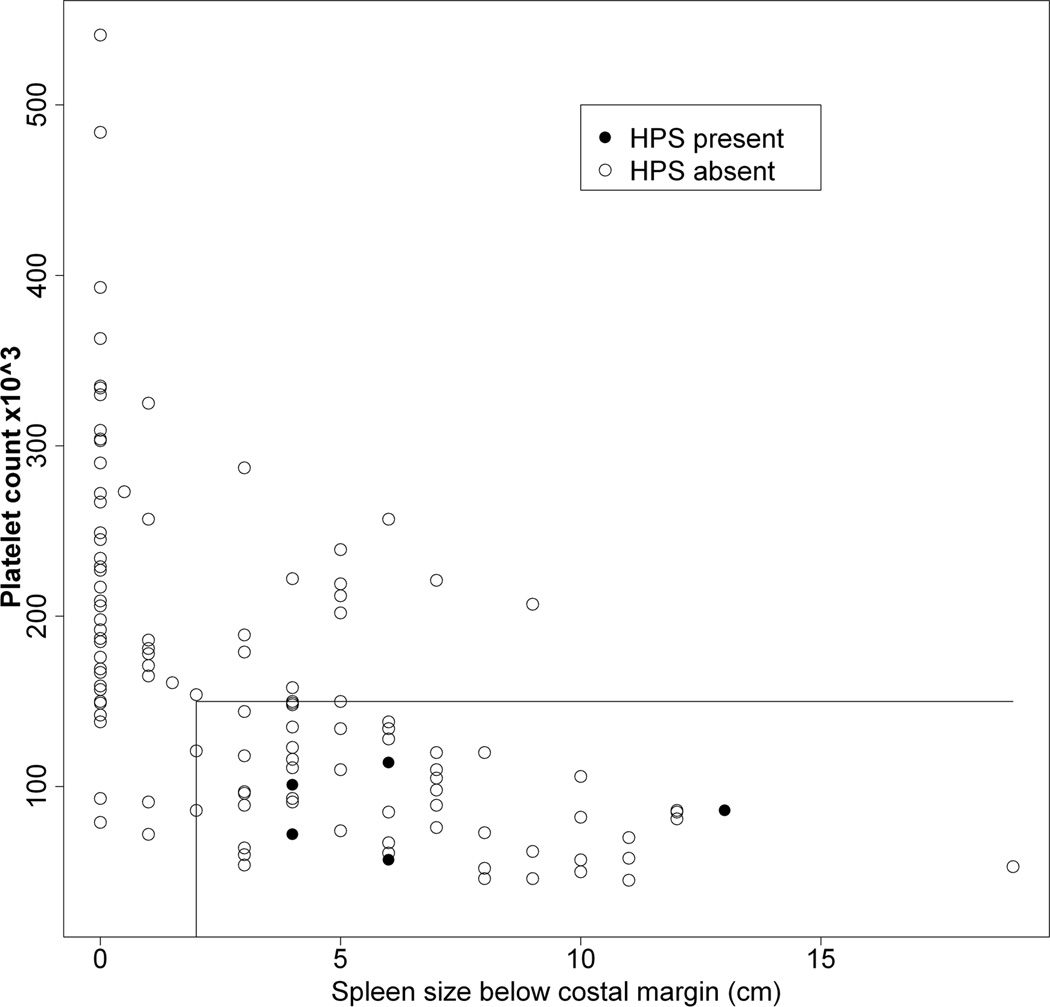

Figures 3A – 3C show the relationship between a history of a complication of PHT relative to platelet count and spleen size (cm below the left costal margin) at the time of study enrollment. Eighty percent of all subjects with either ascites or EV bleed had both low platelets and splenomegaly. Hepatopulmonary syndrome only occurred among patients with both thrombocytopenia and splenomegaly. Conversely, a history of complications was rarely observed among those with normal platelet count and normal spleen size (p < 0.01 for risk of a history of a complication with splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia relative to the absence of splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia at enrollment). With respect to specific complications, a normal platelet count and normal spleen size were present in only 1 of 12 children with ascites (online-only supplemental Fig. 1A, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A164), 3 of the 20 children with EV bleed (online-only supplemental Fig. 1B, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A165), and none of the six children with HPS (online-only supplemental Fig. 1C, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A166; legends for the supplemental figures can be found at http://links.lww.com/MPG/A167).

Figure 3.

A–C: Correlation of history of presence of ascites (3A), esophageal variceal bleed (3B) or hepatopulmonary syndrome (3C) with current platelet count and spleen span below the costal margin. The presence (filled circles) or absence (open circles) of a history of ascites (3A), EV bleed (3B) or HPS (3C) for each subject relative to platelet count (y-axis) and spleen size (cm below the costal margin, x-axis) is shown. The horizontal line represents a platelet count of 150,000, and the vertical line a spleen size of 2 cm below the left costal margin. Thus, individuals whose data points fall to the right of a spleen size of 2 cm (x-axis) and below a platelet count of 150,000 (y-axis) are in the definite PHT category. Note that a large majority of subjects with complications fall within this part of the graph.

Growth Parameters in Portal Hypertension

Because growth failure is a major complication leading to liver transplantation in the younger child or infant, we examined the relationship of growth parameters (expressed as z-scores) to PHT status. Data were expressed as z-scores relative to published age-adjusted normative values. Surprisingly, there was only one significant difference in these parameters among the PHT groups. Height z-score was statistically lower in possible versus absent PHT, although the magnitude of the difference was of questionable clinical significance. None of the parameters were remarkably different from published norms for healthy children (Table 1).

Laboratory Studies Associated with Portal Hypertension

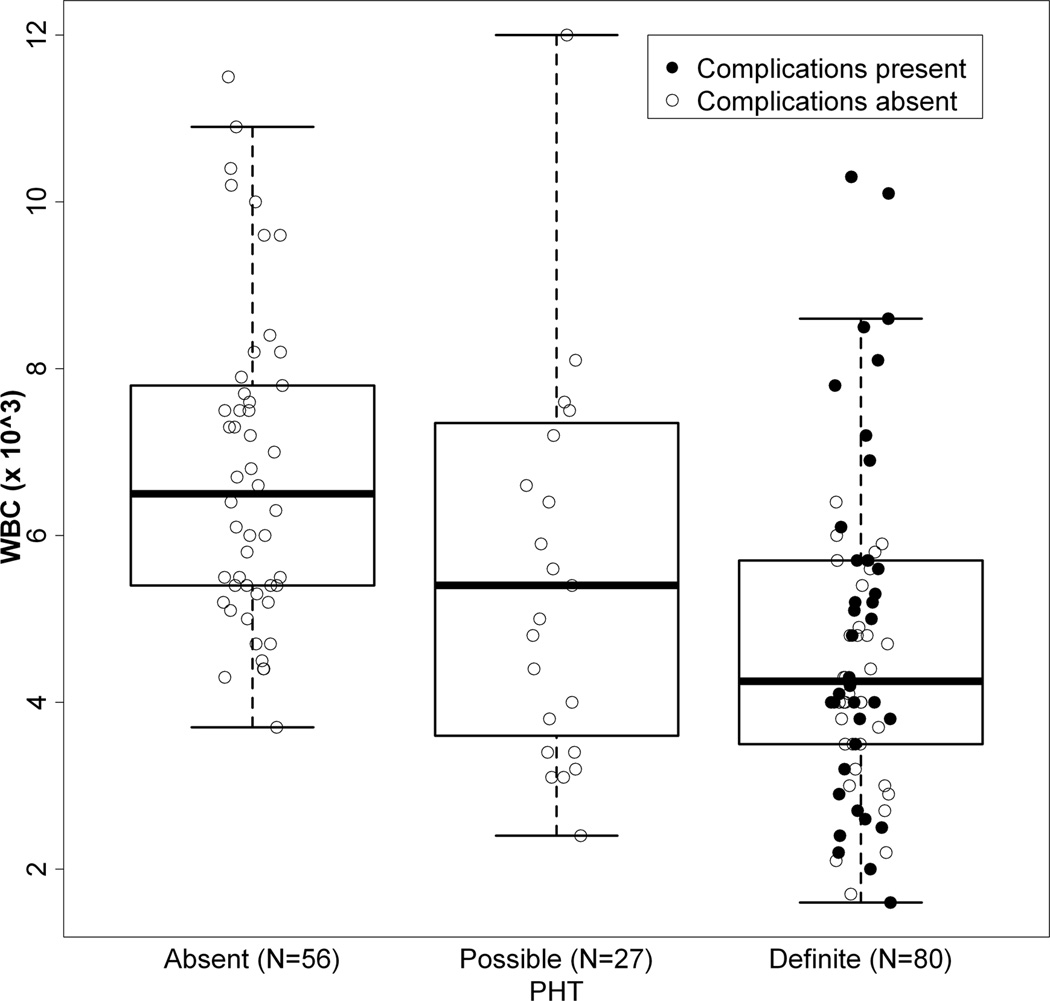

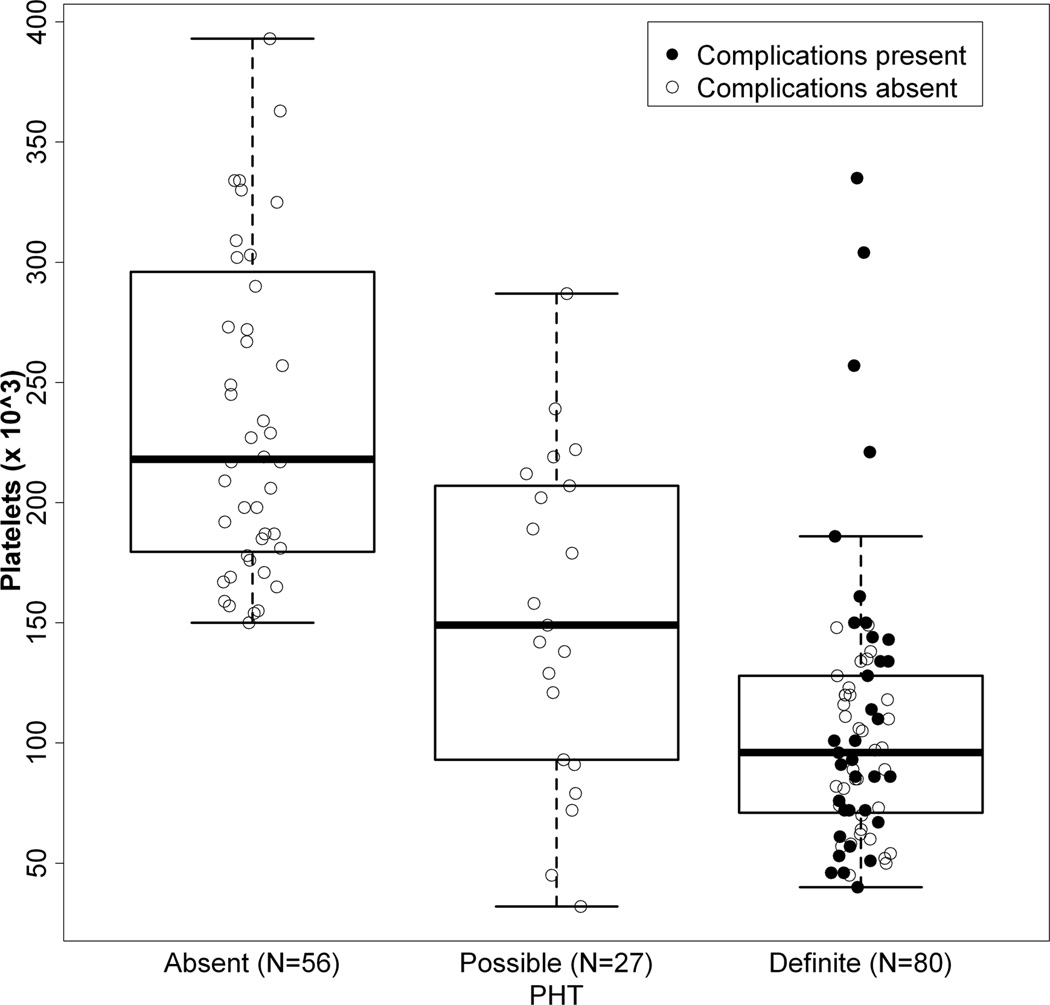

Biochemical and hematologic findings for the three BA groups were examined (Table 2). Comparing definite to absent PHT, significant differences were found in AST, AST/ALT ratio, total bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, white blood cell count, platelet count and a modified AST to platelet ratio (APRI). This modified APRI reflected the AST level in IU/L divided by the platelet count in 103/ml, thereby avoiding issues related to local variability in normative values for AST (19). Values for the possible PHT group were intermediate between definite and absent PHT for AST/ALT ratio, total bilirubin, albumin prothrombin time, platelet count and modified APRI. Interestingly, ALT, AST, and gGTP were higher in possible PHT relative to either definite or absent PHT. The distribution of platelet and white blood cell counts was shifted toward lower values of subjects with definite PHT compared to those without (Figures 4A and 4B). 34% of those with definite PHT had either PT > 15s or albumin < 3 g/L. No subject with definite PHT had a serum Na < 130 mEq/L, while 5 subjects had values between 130 and 135 mEq/L.

TABLE 2.

Laboratory parameters in subjects with BA

| Parameter | PHT definite | PHT possible | PHT absent |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALT* | 88 ± 63 (75)† | 111 ± 106 (24) | 74 ± 75 (54) |

| AST‡,* | 106 ± 70 (74) | 129 ± 128 (24) | 67 ± 51 (54) |

| AST/ALT† | 1.41 ± 0.98 (74) | 1.25 ± 0.43 (24) | 1.13 ± 0.54 (54) |

| γ-GTP* | 151 ± 167 (65) | 235 ± 339 (23) | 124 ± 172 (49) |

| TB‡ | 2.6 ± 5.2 (65) | 1.9 ± 2.2 (16) | 0.7 ± 0.6 (42) |

| Alb‡ | 3.8 ± 0.7 (73) | 4.0 ± 0.6 (23) | 4.3 ± 0.5 (52) |

| PT‡,* | 14.3 ± 1.9 (65) | 13.8 ± 2.3 (22) | 12.7 ± 1.3 (41) |

| Na | 139 ± 7 (57) | 139 ± 3 (16) | 139 ± 3 (25) |

| WBC‡ | 5.2 ± 4.0 (76) | 7.1 ± 6.4 (23) | 6.9 ± 2.1 (50) |

| Plt‡,§,* | 106 ± 55 (71) | 153 ± 68 (21) | 245 ± 87 (44) |

| APRI‖,‡,§ | 1.19 ± 0.92 (69) | 1.09 ± 1.22 (21) | 0.31 ± 0.26 (44) |

Alb = albumin; ALT = alanine transaminase; APRI = aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; BA = biliary atresia; γ-GTP = γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; PHT = portal hypertension; plt = platelet count; PT = prothrombin time; TB = total bilirubin; WBC = white blood cell count.

PHT absent vs PHT possible, significant at α = 0.05.

mean ± standard deviation, number in parenthesis indicates number of subjects with measurement of interest.

PHT definite vs PHT absent, significant at α = 0.05.

PHT definite vs PHT possible, significant at α = 0.05.

Modified APRI = AST level in international unit per liter divided by the platelet count in 103 cell/mL.

Figure 4.

4A and 4B: Distribution of WBC (4A) and Platelet count (4B) relative to PHT status and presence or absence of complications of PHT. Individual value of WBC count (4A) and platelet count (4B) for those individuals defined with Absent, Possible or Definite PHT. Subjects without any history of complication (defined as either ascites, EV bleed or HPS) are represented as open circles, those with complications as filled circles. Box and whisker plots overlay the data. The heavy bar represents the median, the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentile, and the whiskers span 99% of the data if the data were normally distributed.

DISCUSSION

The major strength of this study is that it is contemporary, large, cross-sectional, multi-centered and focused on issues related to PHT. It stems from enrollment into BASIC, one of five protocols currently under study in ChiLDREN. This network consists of 15 clinical sites with a history of institutional strength in the study of pediatric liver disease. One of the principal aims of BASIC is to determine the natural history of BA patients surviving with their native liver The nature of this study excludes children with progressive disease who underwent liver transplantation early in life, especially those with “failed” Kasai procedures. In effect, this is a study of children and young adults with BA who survive with their native livers, representing those children who would be seen in long-term follow-up in clinical practice. By recruiting these patients with BA and following each for up to 10 years, BASIC will record prospectively obtained data in a standardized and uniform fashion on growth and nutrition, physical examination findings, clinical laboratory parameters, and complications from hundreds of BA patients. Thus modeling of the natural history of BA through childhood should be possible with a goal of developing a disease-specific staging system. This multi-centered study differs from the majority of the published experiences to date of the natural history of BA, which are typically retrospective and single-centered (4, 6, 20–22). In addition, much of the literature to date emanates from transplant centers and thus includes a potential referral bias, that being more severe liver disease. The current analysis was devised to minimize this bias. In fact, two thirds of the study subjects underwent their original hepatoportoenterostomy at the ChiLDREN site. Thus, this current analysis lessens the impact of referral center bias and has a greater sampling of the “real world” status of long-term survivors with BA in a non-centralized health care delivery system. Moreover, this cohort will serve as the basis for determining the timeline and incidence of the development of PHT in BA.

One of the major complications of BA is the development of PHT. Previous reports have documented a high percentage of BA survivors with PHT (9, 10, 12). Often PHT is defined by development of a complication or by endoscopic findings. These are late manifestations of the development of PHT and likely underestimate the prevalence of PHT. Surveillance endoscopy of children with cirrhosis is not undertaken by many pediatric gastroenterologists and therefore using the presence of varices as a marker of PHT may not be practical (14, 15). One of the goals of the current study was the establishment of clinically-accessible and reproducible operational criteria to define PHT in BA, which could be used as end-points in prospective follow up and for the development of studies of interventions, outcomes, and new modalities for assessing PHT (e.g. doppler sonographic parameters or elastography). The current clinical criteria for PHT appear to be useful in this regard, although it should be remembered that this is a clinical and not hemodynamic definition of PHT. Although impractical in children, direct measurement of portal venous pressures would likely yield a larger percentage of long term BA survivors with PHT.

It would be valuable to have noninvasive markers of PHT for prospective follow up in children with BA and other progressive liver diseases. This study utilized platelet count as one of the parameters defining PHT, so results involving platelet counts may be in part a self-fulfilling prophecy. It is noteworthy that the clinically defined PHT correlated with white blood cell count, an independent marker of hypersplenism. The data indicate that those patients meeting clinical criteria for PHT (spleen size and platelet count at the time of study enrollment), accounted for most of the patients who had previous portal hypertensive complications. Gana et. al. recently derived a clinical prediction rule for the presence of esophageal varices in children. Platelet count, spleen length determined by ultrasonography and serum albumin were independent variables with the best fit, however few patients with BA were included in the study (23). Fagundes et al. indicated that children with cirrhosis and splenomegaly on clinical examination were 14.6 fold more likely to have esophageal varices than cirrhotic children without splenomegaly (24). In a single study, splenomegaly had better sensitivity and specificity for predicting varices in BA compared to transient elastography (25). At present, however, there are no well-accepted noninvasive markers for the development of esophageal varices in children (26). Our analysis in children with BA suggests that modeling spleen size (cm below the costal margin) and platelet count may be useful as a surrogate marker for the risk of development of complications of PHT. A validated scoring system using these easily obtainable and inexpensive parameters might also be used for comparative analyses with other biomarkers and as an outcome for the effect of various clinical interventions, especially those directed at slowing fibrogenesis.

The AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) has been postulated as a potentially accurate marker of increasing fibrosis in adult patients with hepatitis C (19, 27). Limited work has examined the APRI in chronic viral hepatitis in children (25) and very recently in a small cohort of BA patients (26). APRI positively correlated with hepatic fibrosis (28, 29). In our current analysis, APRI was increased in those meeting criteria for definite PHT. How well this index predicts clinical markers of PHT and portal hypertensive complications, other biochemical measures of hepatic functional compromise and increased fibrosis on liver biopsy will be addressed with subsequent prospective analyses of longitudinal data collected in the BASIC cohort.

As might be expected, variceal hemorrhage was a common complication observed in this cohort of children. The age at onset of variceal hemorrhage was quite variable. One third of those subjects who had suffered from variceal hemorrhage survived with their native liver for at least another 5 years, confirming a prior report of relatively good prognosis after variceal hemorrhage in patients with BA who had low bilirubin levels (7). The nature of the BASIC BA cohort excluded children who had already undergone liver transplantation and thus who might have had higher rates of complications. The more severe BA complications reported by Duche et al. whose study group had significantly higher bilirubin levels than this cohort, may not be as common in the current era in which some patients with failed portoenterostomies undergo “pre-emptive” transplantation before development of PHT complications (1, 12).

It is surprising that the children in this cohort, a large percentage of whom have PHT, are “relatively” healthy. Sicker patients certainly have been, in effect, censored by the process of liver transplantation. This is particularly true for hepatopulmonary syndrome, which in its own right may be an indication to proceed with transplantation. Growth parameters overall were fairly unremarkable and failure to thrive was not generally observed in those with definite PHT. Failure to thrive can be an indication for liver transplantation, although not typically in isolation. Thus it is possible that prior transplantation may have selected for a cohort of children without significant nutritional compromise. Laboratory parameters of liver function were modestly diminished in those with PHT; most of the children would be classified as having compensated cirrhosis. None of the children had significant hyponatremia, a marker of more advanced liver disease. Prospective follow-up of this cohort in the ensuing 5 to 10 years will provide unique insights of the natural history of BA in children surviving with their native liver.

In conclusion, this multi-centered analysis of PHT in BA patients is representative of clinical management in the current era. Clinically definable PHT is present in two thirds of North American long-term BA survivors. The presence of PHT coincides with measures of hepatic injury and dysfunction, although in this selected cohort the degree of hepatic dysfunction is mild. Growth is relatively unimpaired in this cohort, even in the presence of PHT. In light of the compensated nature of the PHT in these children and young adults with BA, future efforts need to be focused on understanding those factors that predict progression of PHT and the development of adverse outcomes with the goal of ultimately optimizing medical management. The ChiLDREN BASIC study is ideally suited to prospectively investigate these important issues and to provide baseline information for future interventional trials of the management of portal hypertension in children (16).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support - This work was supported by the National Center for Research Resources (5M01 RR00069 [RJS], UL1RR025780 [Colorado], UL1RR024153[Pittsburgh], UL1RR024134 [Philadelphia], UL1RR024131 [San Francisco], UL1RR025005 [Baltimore], UL1RR025741 [Chicago]), UL1RR029877 [New York] and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK 62453 [RJS], DK 62497 [AGM], DK 62481 [BAH], DK 62470 [SJK], DK 62500 [PR], DK 62530 [KS], DK 62445 [NK], DK 62466 [BLS], DK 62456 [JCM], DK 62452 [YT], DK 62436 [LB], DK 84585 [RR].

Abbreviations

- ChiLDREN

Childhood Liver Disease Research and Education Network

- BA

biliary atresia

- PHT

portal hypertension

- BASIC

Biliary Atresia Study of Infants and Children

- EV

esophageal varices

- APRI

aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jpgn.org).

Contributor Information

Benjamin L. Shneider, Email: Benjamin.Shneider@chp.edu.

Bob Abel, Email: Abelr@umich.edu.

Barbara Haber, Email: HABER@email.chop.edu.

Saul J. Karpen, Email: skarpen@bcm.tmc.edu.

John C. Magee, Email: mageej@med.umich.edu.

Rene Romero, Email: Rene.Romero@choa.org.

Kathleen Schwarz, Email: kschwarz@jhmi.edu.

Lee M. Bass, Email: LBass@childrensmemorial.org.

Nanda Kerkar, Email: Nanda.Kerkar@mssm.edu.

Alexander G. Miethke, Email: Alexander.Miethke@cchmc.org.

Philip Rosenthal, Email: prosenth@peds.ucsf.edu.

Yumirle Turmelle, Email: Turmelle_Y@kids.wustl.edu.

Patricia R. Robuck, Email: RobuckP@EXTRA.NIDDK.NIH.GOV.

Ronald J. Sokol, Email: Ronald.Sokol@childrenscolorado.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shneider BL, Mazariegos GV. Biliary atresia: a transplant perspective. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1482–1495. doi: 10.1002/lt.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duche M, Fabre M, Kretzschmar B, Serinet MO, Gauthier F, Chardot C. Prognostic value of portal pressure at the time of Kasai operation in patients with biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:640–645. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000235754.14488.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laurent J, Gauthier F, Bernard O, Hadchouel M, Odievre M, Valayer J, Alagille D. Long-term outcome after surgery for biliary atresia. Study of 40 patients surviving for more than 10 years. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1793–1797. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90489-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davenport M, Kerkar N, Mieli-Vergani G, Mowat AP, Howard ER. Biliary atresia: the King's College Hospital experience (1974–1995) J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:479–485. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stringer M, Howard E, Mowat A. Endoscopic sclerotherapy in the management of esophageal varices in 61 children with biliary atresia. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1989;24:438–492. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(89)80397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tagge D, Tagge E, Drongowski R, Oldham K, Coran A. A long-term experience with biliary atresia. Ann. Surg. 1991;214:590–598. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199111000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miga D, Sokol R, MacKenzie T, Narkewicz M, Smith D, Karrer F. Survival after first esophageal variceal hemorrhage in patients with biliary atresia. J. Pediatr. 2001;139:291–296. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.115967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Heurn LW, Saing H, Tam PK. Portoenterostomy for biliary atresia: Long-term survival and prognosis after esophageal variceal bleeding. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lykavieris P, Chardot C, Sokhn M, Gauthier F, Valayer J, Bernard O. Outcome in adulthood of biliary atresia: a study of 63 patients who survived for over 20 years with their native liver. Hepatology. 2005;41:366–371. doi: 10.1002/hep.20547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hung PY, Chen CC, Chen WJ, Lai HS, Hsu WM, Lee PH, Ho MC, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with biliary atresia: a 25 year summary. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:190–195. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000189339.92891.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shinkai M, Ohhama Y, Take H, Kitagawa N, Kudo H, Mochizuki K, Hatata T. Long-term outcome of children with biliary atresia who were not transplanted after the Kasai operation: >20-year experience at a children's hospital. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:443–450. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0b013e318189f2d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duche M, Ducot B, Tournay E, Fabre M, Cohen J, Jacquemin E, Bernard O. Prognostic value of endoscopy in children with biliary atresia at risk for early development of varices and bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1952–1960. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miraglia R, Luca A, Maruzzelli L, Spada M, Riva S, Caruso S, Maggiore G, et al. Measurement of hepatic vein pressure gradient in children with chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2010;53:624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shneider B. Approaches to the management of pediatric portal hypertension: Results of an informal survey. In: Groszmann R, Tygat N, Bosch J, editors. Portal hypertension in the 21st century. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shneider B, Bosch J, de Franchis R, Emre S, Groszmann R, Ling S, Lorenz J, et al. Portal hypertension in children: Expert pediatric opinion on the report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on the methodology of diagnosis and management of portal hypertension. Pediatr Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01652.x. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling SC, Walters T, McKiernan PJ, Schwarz KB, Garcia-Tsao G, Shneider BL. Primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage in children with portal hypertension: a framework for future research. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:254–261. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318205993a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inc. SI. SAS/STAT User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karrer F, Price M, Bensard D, Sokol R, Narkewicz M, Smith D, Lilly J. Long-term results with the Kasai operation for biliary atresia. Arch. Surg. 1996;131:493–496. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430170039006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valayer J. Conventional treatment of biliary atresia: long-term results. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1546–1551. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wildhaber BE, Coran AG, Drongowski RA, Hirschl RB, Geiger JD, Lelli JL, Teitelbaum DH. The Kasai portoenterostomy for biliary atresia: A review of a 27-year experience with 81 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1480–1485. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gana JC, Turner D, Roberts EA, Ling SC. Derivation of a clinical prediction rule for the noninvasive diagnosis of varices in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:188–193. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181b64437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagundes ED, Ferreira AR, Roquete ML, Penna FJ, Goulart EM, Figueiredo Filho PP, Bittencourt PF, et al. Clinical and laboratory predictors of esophageal varices in children and adolescents with portal hypertension syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:178–183. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318156ff07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chongsrisawat V, Vejapipat P, Siripon N, Poovorawan Y. Transient elastography for predicting esophageal/gastric varices in children with biliary atresia. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shneider B, Emre S, Groszmann R, Karani J, McKiernan P, Sarin S, Shashidhar H, et al. Expert pediatric opinion on the Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10:893–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2006.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaheen AA, Myers RP. Diagnostic accuracy of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: a systematic review. Hepatology. 2007;46:912–921. doi: 10.1002/hep.21835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Ledinghen V, Le Bail B, Rebouissoux L, Fournier C, Foucher J, Miette V, Castera L, et al. Liver stiffness measurement in children using FibroScan: feasibility study and comparison with Fibrotest, aspartate transaminase to platelets ratio index, and liver biopsy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:443–450. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812e56ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SY, Seok JY, Han SJ, Koh H. Assessment of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis by aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index in children with biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:198–202. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181da1d98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.