Abstract

Indian health system is characterized by a vast public health infrastructure which lies underutilized, and a largely unregulated private market which caters to greater need for curative treatment. High out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditures poses barrier to access for healthcare. Among those who get hospitalized, nearly 25% are pushed below poverty line by catastrophic impact of OOP healthcare expenditure. Moreover, healthcare costs are spiraling due to epidemiologic, demographic, and social transition. Hence, the need for risk pooling is imperative. The present article applies economic theories to various possibilities for providing risk pooling mechanism with the objective of ensuring equity, efficiency, and quality care. Asymmetry of information leads to failure of actuarially administered private health insurance (PHI). Large proportion of informal sector labor in India's workforce prevents major upscaling of social health insurance (SHI). Community health insurance schemes are difficult to replicate on a large scale. We strongly recommend institutionalization of tax-funded Universal Health Insurance Scheme (UHIS), with complementary role of PHI. The contextual factors for development of UHIS are favorable. SHI schemes should be merged with UHIS. Benefit package of this scheme should include preventive and in-patient curative care to begin with, and gradually include out-patient care. State-specific priorities should be incorporated in benefit package. Application of such an insurance system besides being essential to the goals of an effective health system provides opportunity to regulate private market, negotiate costs, and plan health services efficiently. Purchaser-provider split provides an opportunity to strengthen public sector by allowing providers to compete.

Keywords: Equity, health insurance, health financing, India, universal healthcare

Introduction

Indian health system has registered remarkable achievements since independence in various key health indicators.(1) However, much remains desired with major weaknesses in healthcare organization, financing, and provision of health services.(2) Of the three issues highlighted, health financing in India has been center of major debate. Demographic (ageing of population), epidemiological (rising spectrum of cost-intensive non-communicable diseases), and social (increased awareness and expectations of consumers of healthcare for technologically advanced care) transitions in health has spiraled the healthcare treatment costs multifold. This has led to impoverishment of India's poor with estimates suggesting one fourth of all hospitalizations leading to indebtedness.(3) Large informal sector and asymmetry of information between insurer and beneficiary pose challenge for using social and private health insurance (PHI), respectively. The present article reviews India's health financing structure with focus on risk pooling and outlines a reform package to strengthen health insurance system with triple objectives of ensuring efficiency, equity, and high-quality care.

Health Financing in India

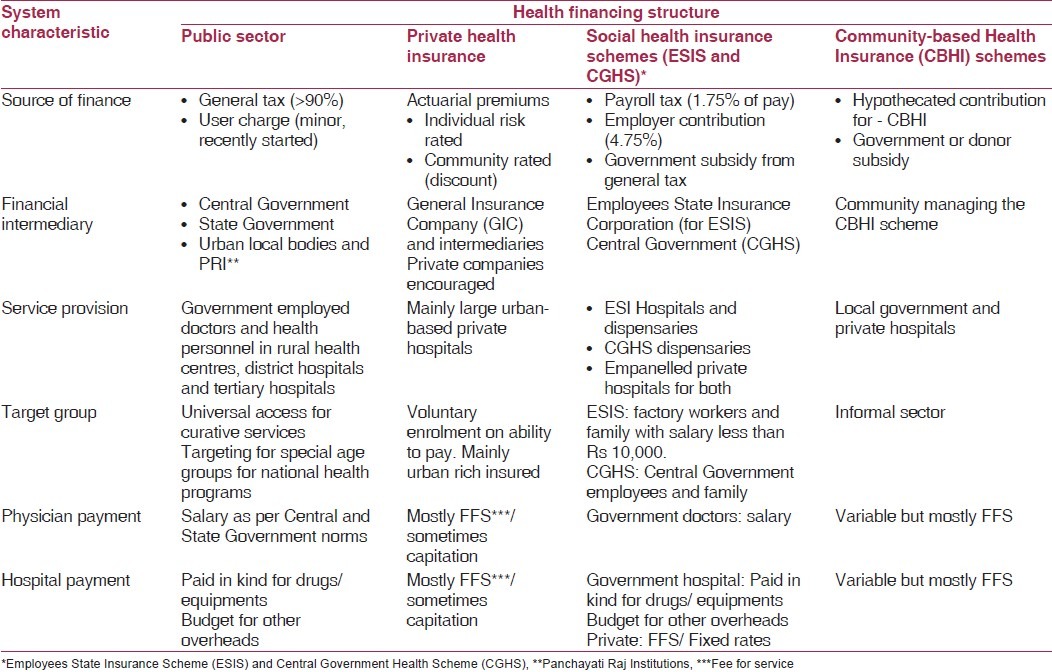

A simplistic scheme to describe the current mechanism for financing healthcare in India has been tabulated [Table 1]. Although it does describe the main tenets, it does not illustrate the impact of this structure on financial protection of people, one of the important goals of the health system.(4) Almost 80% and 40% outpatient and inpatient care, respectively, is sourced from private sector. Although healthcare expenditure constitutes almost 5% of gross domestic product (GDP), contribution of Government is only 0.9% of GDP.(5,6) Majority (71%) of healthcare expenditure is drawn from out-of-pocket (OOP) at time of service utilization which has catastrophic implications for the household. A recent report shows that percentage of persons below poverty line (BPL) at 1$ per day in India increased by 3.7% after the OOP expenditures were accounted for.(7) Furthermore, healthcare costs for outpatient and inpatient care are inflating by 15% and 31%, respectively.(8) Thus, the moral ground of protecting India's poor from spiraling costs of healthcare forms an imperative argument to analyze the current financing system and institute a robust risk pooling mechanism.

Table 1.

Health financing structure in India

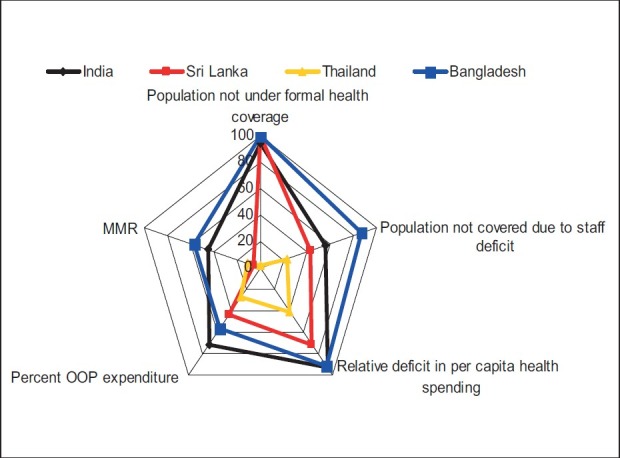

To further the argument, it needs to be noted that health expenditure as percentage of GDP in India (5%) is higher than other Asian countries–China (4.7%), Malaysia (4.2%), Sri Lanka (4.1%), Thailand (3.5%), Pakistan (2.1%), and Bangladesh (2.8%); however, public spending as percentage of total health expenditure is significantly lower in India (19%) than all these countries except Pakistan.(5) Of the total 1201 INR per capita spent on healthcare in India, Government (both Central and State combined) spending is only 242 INR per capita. Problems of access to healthcare in India are further compounded by a lack of effective universal social security program. Figure 1 compares the extent of social security in India and other comparable Asian economies.

Figure 1.

Deficit of social health protection in India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Thailand Source: Author Analysis, Based on data from ILO (2010)(28)

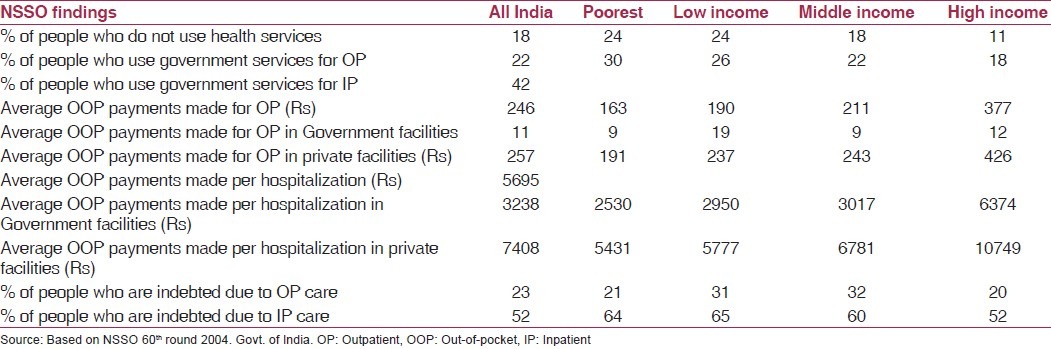

National Sample Survey (NSS) 60th round (2004-05) reports that there are significant barriers to utilization of healthcare as a result of high OOP health expenditures.(9) Twenty eight percent and 20% respondents in rural and urban areas, respectively, who did not access health services for an ailment during the past 15 days, cited financial problem as the reason for their non-utilization of healthcare [Table 2].

Table 2.

Out-of-pocket payments and indebtedness in some states in rural India

Risk Pooling Mechanisms in India: Analysis from Efficiency, Equity, and Quality Lens

Public sector

Government of India uses revenue generated through general taxation to fund public sector which provides preventive and curative healthcare services.(10) General taxation is reported to be the most progressive mechanism to fund healthcare services followed by value-added taxes, social health insurance (SHI), PHI, and OOP in decreasing order.(11) Government tax financing theoretically scores high on equity.

Of the two principal-agent relationships which exist in government sector delivery; i.e., patient-doctor and government-doctor; latter is of greater interest to the current discussion. Government acts as a principal and appoints doctors to serve as agents in delivery of quality healthcare. Fixed salary as payment for services, and poor infrastructure and equipment provide little incentive for the doctors to perform in the interest of its principal to provide quality care. Profits in market drive entry of greater suppliers for competition. Minimal financial gain does not provide any incentive to doctors to enter government services and thus perennial shortage against sanctioned staff posts and staff absenteeism.(12)

Private health insurance in India

PHI in India began with the establishment of General Insurance Corporation (GIC).(13) A large number of private companies were merged into four subsidiaries of GIC, which although had a regional dominance, yet operated at a national scale. Government has encouraged privatization of health insurance market in India with passage of Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA) Bill in 1999.(14)

PHI works on the principle of risk susceptibility. Estimation of premium requires a precise knowledge of the probability of falling ill and the expected loss of income in the event of care post-illness.(15) However, individuals know the probability of their falling ill more than the insurer. This asymmetry of information between insurer and insured places latter at an advantage to conceal their pre-existing illness.(16) Greater enrolment of “bad risk,” i.e., those with higher probability of falling ill, leads to adverse selection and makes insurance unsustainable in private market.(17) Insurance companies either raise premiums or indulge in “cream skimming.” Adoption of former, i.e., raising premiums drives healthy people out of market whose marginal benefit of insurance underscores marginal cost. This leads to a situation wherein the insured population is comprised even more by the relatively unhealthy, which ultimately results in higher claim ratio (proportion of insured population seeking reimbursement for treatment undertaken), thereby raising cost to insurance company. Such a situation leads to a spiral whereby insurance companies raise premiums which drives out healthy population out of market and relatively sicker people insuring themselves, which further drives up premiums in following year. Ultimate outcome of this process is failure of insurance which is referred to as “death spiral.”(18) Cream skimming is a practice whereby the insurance companies selectively insure those who are healthy, i.e., lesser risk of falling ill and seeking treatment. Cream selection by insurer again contravenes the principle of equity as generally poor and elderly are ones at higher risk of disease and are excluded by insurer. Estimation of probability of falling ill is also complicated by ex-ante moral hazard, i.e., as a result of insurance, those who are insured, indulge in behavior which increases likelihood of falling ill.

Besides knowledge of risk of falling ill, second information required for calculating premium is “expected loss of income” in event of disease. Ex-post moral hazard, i.e., greater utilization of healthcare by insured after insurance and; supplier-induced demand arising as a result of information asymmetry with doctor acting as an imperfect agent to patient, leads to increase in cost of medical care.(16) To conclude, private insurance based on profit motive is theoretically difficult, if not impossible, to operate in healthcare market in view of problems of information asymmetry leading to adverse selection, moral hazard, and supplier-induced demand.

Evidence from developing countries such as Chile and Uruguay indicates inequity of actuarial PHI.(19,20) In a country with 9.2% population in over 60 years of age group in Chile, the proportion of >60 years population enrolled under private insurance was only 3.2%.(19) Evidence from India also points at inequitable impact. High administrative cost of PHI (20-32%) undermines its efficiency as against SHI schemes (5-14.6%), i.e., Employees State Insurance Scheme (ESIS) and Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS).(21) There is abundant theoretical basis (moral hazard and supplier-induced demand) and empirical evidence from other countries that private insurance drives up healthcare expenditure.(15) Moreover, in Indian context, where PHI mainly contracts with urban-based corporate hospitals, it is likely to increase cost.(22)

Social health insurance in India

ESIS and CGHS are two main SHI schemes operating in India for factory workers and central government employees, respectively.(23) However, the two schemes have been under immense criticism for being inefficient and poor in quality of care.(24) Attempts at expanding social healthcare insurance are complicated by large informal sector, lack of understanding of solidarity-based insurance, inadequate data on costing, unregulated private market, and poor standards of public healthcare delivery.

Community-based health insurance

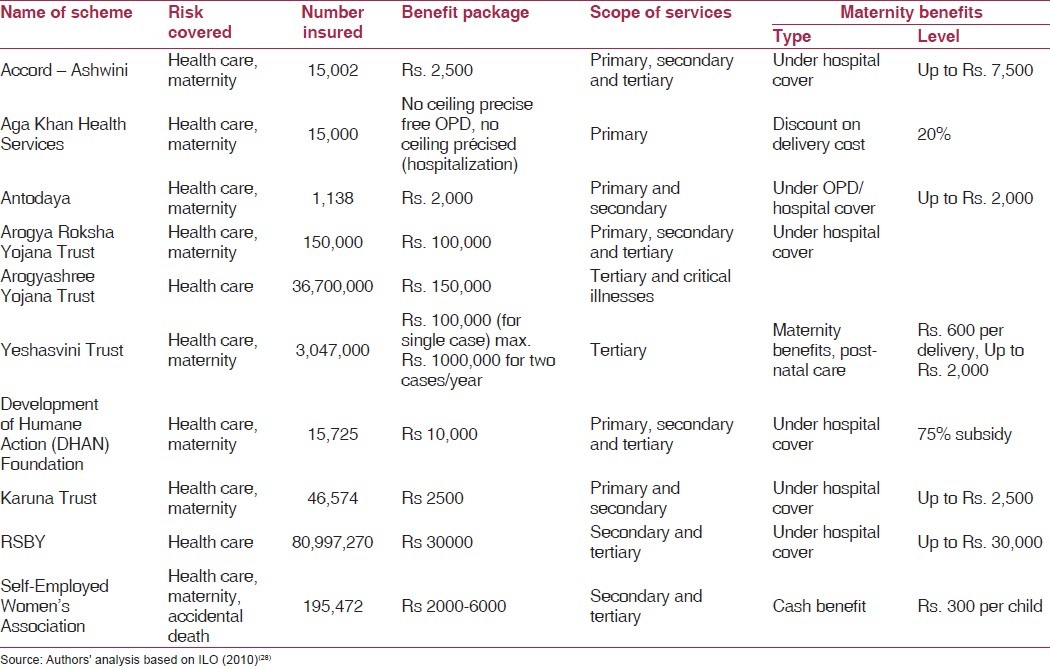

Numerous community-based health insurance (CBHI) schemes hugely diverse in terms of design or implementation, coverage, and target groups exist in India [Table 3].(25–28) A review of these schemes highlights importance of many contextual factors (political will, social capital) for their success, with an evidence of increasing trend toward GIC-collaborated schemes.(29) There in increasing dependence on donor funds or government subsidy for sustainability, evidence of adverse selection, and inequity with inadequate coverage of poorest among poor. Overall, there is inconclusive evidence on impact of CBHI schemes on the health system goals and further doubts over replicability and upscaling of these initiatives which may entail huge administrative costs.(30)

Table 3.

Summary of salient micro-insurance initiatives in health in India

Among the schemes, three main patterns of scheme ownership and management emerged.(30–32) First, in many schemes, the NGO running the insurance scheme is also the healthcare provider. Such provider-owned schemes account for most of the schemes reviewed. For example, the Voluntary Health Services (VHS, Chennai) runs a Medical Aid Plan under which households pay an annual premium (graded according to joint monthly income) directly to VHS, and in return they are provided with a free annual health check-up, and discounted rates on outpatient and inpatient services. Second, there are several NGO-owned schemes where the NGO is the insurer, but does not provide healthcare itself (e.g., KKVS, RAHA, and Tribhuvandas Foundation). This is a simple “third-party payer” arrangement. Third, several of the schemes involve an NGO acting as an intermediary between the target population and one of the GIC subsidiaries (ACCORD, Seba, and SEWA) or in one case, between the target population and a new private-for-profit insurance scheme (WWF). SEWA is an example of an NGO-intermediated scheme.

Most existing studies have focused on the impact of community financing programs on healthcare utilization and financial protection.(33–35) A recent study evaluated the impact of India's Yeshasvini CBHI program on healthcare utilization, financial protection, treatment outcomes, and economic well-being.(36) This study found the program to have increased utilization of healthcare services and reduced OOP spending, with better health and economic outcomes among the insured. However, more specifically, these effects vary across socioeconomic groups and medical episodes. The article demonstrates that community insurance presents a workable model for providing high-end services in resource-poor settings through an emphasis on accountability and local management.

Rashtriya swasthya bima yojana

Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India, in 2007, promulgated a new scheme for providing health insurance to unorganized sector workforce which comprises 94% of India's total working population. This scheme is targeted toward the BPL households and uses the BPL list of Planning Commission as the proxy-means test. Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) scheme has suddenly catapulted the proportion of India's population under insurance cover from 3 to 4% (2005) to about 15% (2010) and hopes to increase the same to 30% by 2015.

The highlights of this scheme are its paperless transaction, portability of benefit, and being cashless to beneficiary. The hallmark of RSBY is the choice to beneficiary between a list of Government and private empanelled providers. RSBY is being lauded to hold much promise for the secondary healthcare in India. The scheme has been designed with utmost care to being responsive to needs of the population, along with having a business model so that all stakeholders have an incentive to carry forward the scheme. However, this scheme needs to be evaluated to diagnose the maladies of health insurance viz. cream skimming, moral hazard, etc., at the earliest. RSBY is supported by a strong technology basis of a “smart card” technology which allows for near-real-time tracking of program. This technology also holds promise for being loaded with other social sector subsidies such as education subsidy, fertilizer subsidy, and public distribution system; besides providing an opportunity to convert the smart-card into an e-health card which holds all information related to preventive maternal and child healthcare for the household.

Way Forward: Reforming the Health Insurance System

Institutionalization of universal health insurance scheme

Benefit package

It has been rightly argued that even if Government of India radically enhances its budgetary outlay by 50%, private expenditure on health can be reduced from 77% to 62%.(23) This emphasizes the need for rationing and the right “benefit package” as it may not be feasible to provide for entire gamut of health services. A package which is enough to keep marginal benefits of joining insurance higher than marginal costs for the poorest would be appropriate.

We recommend to include both outpatient and inpatient care. Hospitalizations should include emergency care, reproductive and child care, minor and selected elective surgical and specialist care. It should also include basic chronic care management. Preventive services should be the mainstay of the program which should include immunization, antenatal care, health education, and screening for chronic diseases. The exact benefit package should be region or state specific as a one-size-fit-all package is inappropriate to meet the diverse needs of Indian population. Finalization of a benefit package should be followed by its costing.

We do recognize the problems of managing moral hazard with OPD care; hence, it is suggested to begin with preventive and secondary care. OPD care can gradually be added once the experience and Management Information System (MIS) is sufficiently robust to monitor potential fraud. Having OPD care can be efficient as it can improve health-seeking behavior for diseases at an early stage rather than seeking treatment at a late complicated stage.

Coverage and risk pooling

Recent analysis have questioned sustainability of universal healthcare provision in one go.(2,37) Hence, the benefit package can begin with a targeting mechanism and be gradually expanded to entire population later. Such “progressive universalism” has been shown to have beneficial impact from an equity viewpoint.(38,39)

Universal Health Insurance Scheme (UHIS) should be increased in coverage from its current focus on BPL to covering the entire population. Premium should be based on ability to pay and linked to collection of direct general tax revenue. Government would be required to heavily subsidize BPL from general tax revenue. Experience from Thailand shows that the coverage of risk pooling scheme can be universalized most rapidly once it is linked to general tax revenue. Enrolment should be mandatory to generate extra resources from rich and to create a large risk pool to cross-subsidize poor and high risks.

Revenue collection needs to be decentralized; however, risk pooling should be done at national level in order to circumvent state-specific income and cost of care differentials. Different states in India are in different phases of health transition. Although some states have shifted to a phase where non-communicable chronic diseases are predominant, other states are still grappling with the problem of acute infectious diseases. Chronic diseases entail greater cost of treatment. The suggestion of risk pooling at the national level holds even more importance in a situation wherein different states have different gradients of need for costlier forms of treatment for chronic diseases. Having a national level is beneficial in such situations as it helps to cross-subsidize areas with greater need with contributions from areas with lesser need. This is in essence the principle of risk-pooling. For the same reason of cross-subsidization across states, we believe that going with state-level risk pools will be inequitable to poorer states. Considering large differentials in income-generating capacities of different states, and need for curative health care, a risk adjustment mechanism needs to be worked out for efficient allocation of resources.

Provider mix and payment mechanism: Demand and supply side risk sharing

The scheme should be operated through both public and private mix of providers. This is considering the poor access of public health infrastructure, especially in remote and disadvantaged areas. It is envisaged to increase access for poor and generate competition to drive efficiency. The scheme should be cashless at point of use to insured. Possibility of greater utilization of services by rich, leading to inequity, should be prevented by having demand side cost-sharing mechanisms (deductibles and copayments) for richer and exempting the poor from any cost sharing. Private providers should be paid on a capitation basis for outpatient care, and on case-mix or diagnostic-related group basis for inpatient care. Government as monopsonistic health purchaser (i.e., single purchaser in a larger geographic area can exert its influence on the contracting terms with providers) allows greater negotiation power for prices. Introducing purchaser-provider split in provision of healthcare, along with including private providers for competition, is envisaged to enhance efficiency. Case-mix payment system has been done successfully in past in schemes like “Chiranjeevi” in Gujarat, for utilization of maternity services.(40) It entails supply-side risk sharing to provide incentives for providers to act efficiently. Preventive care needs to be paid on fee-for-service basis to enhance its supply and coverage. Public providers, traditionally paid on salary basis, need to be paid graded bonus incentives over their salary, on accomplishment of a well thought of performance measurement matrix which should include indicators of quantity and quality of curative and preventive care. Public providers will also need to be given autonomy with accountability. Unless public sector institutions are given autonomy and incentives, it is unlikely that they will compete for insurance fund. Initial experience with the RSBY in Kerala has suggested that provision of incentives at Government healthcare facilities is an effective strategy to strengthen the public sector utilization and improving its infrastructure.

Role of private, social, and community health insurance

PHI should be provided on a complementary basis to cover for illnesses not covered under the “basic benefit package”. Another role for private insurance companies with their infrastructure can be collection of premiums and acting as third party administrators.

It is proposed to merge the existing SHI schemes with UHIS. This will create an efficiency of economies of scale. Moreover, it is proposed to increase coverage of SHI by keeping no ceiling on income for enrolment, which is currently the practice [Table 1]. This will create greater risk pool and additional resources overall.

CBHI schemes have been historically seen as precursor to development of SHI schemes. Moreover, Government needs to encourage development of such schemes through subsidies and technical support since they have potential to provide risk pooling for informal sector, building awareness for insurance, and harnessing social solidarity.(41)

Contextual factors: Opportunities and threats

Gill Walt's framework for assessing health policy is useful in evaluating opportunities and threats for instituting a health insurance system in India.(42) Experience from Thailand's “30 Baht treat all disease” Universal Coverage scheme is handy in the present discussion.(43) Thailand, in late 20th century, was marked by a period which witnessed strong political will for investing in health with an emphasis on equity, despite economic crisis and national debt. This is evident in reallocation of budget from urban provincial hospitals to rural health centers, whose budget actually saw an increase during the period. There was a close relationship between the reformist politicians and bureaucracy, and the researchers. All these contextual factors favored introduction of the universal coverage scheme.

On a similar note, the contextual factors in India seem to present a positive frame. India is witnessing an economic boom during the past 5 to 6 years, with optimistic forecasts of growth of GDP by almost 8 to 10% in 2010. Prime Minister's national Common Minimum Program places high priority to investment in social sectors such as education and health. National Rural Health Mission has marked a steep increase in the budgetary allocation to health departments.(44) Decentralization of financial and administrative powers has led to timely disbursement and utilization of allocated funds. Enhanced managerial, accounting, and technical support is available at district level and below to manage increased funds flow. Research inputs highlight the inequitable state of largely privately funded healthcare system. Moreover, Government of India has shown interest in the idea of health insurance with piloting of cashless UHIS for the BPL families. Macroeconomic Commission on Health strongly argues for a case of SHI in India. Thus, the contextual factors, problem statement, and possible solution provide a “window of opportunity” for reformers and researchers to push forward the agenda of universal health insurance in India.

Fiscal sustainability of a universal health care package is cited as a challenge. The high level expert group (HLEG) has submitted its draft recommendations on what course should be adopted in India in terms of financing and delivering services for universal health care (UHC). The HLEG estimates that financing the proposed UHC system will require public expenditures on health to be stepped up from around 1.2% of GDP today to at least 2.5% by 2017 and to 3% of GDP by 2022. Using three different cost estimates assumptions from Thailand, Mexico and India and making adjustments for income differences and inflation, Mahal et al (2011) estimate for providing health care to 90% population ranged from less than 2% of GDP (with Mexico costs) to greater than 4.3% (with Thailand costs).(45) Another recent paper found that the cost of universal health care based on a benefit package on lines of Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) delivered through a combination of public and private providers would be INR 1713 per capita per year, which amounts to 3.8% (2.1-6.8) of GDP in India.(46)

Conclusions

We concede that universalizing the health insurance is not the sole answer to India's health system problems. It entails major revamping of governance and management capacity, infrastructure, management information system, and regulatory frameworks. Special efforts are needed to upgrade the MIS system, which will be critical to success of monitoring of insurance claims, setting premiums, and establishing risk pools. Unregulated private sector market with lack of quality accreditation requires attention. Inclusion of private providers for provision of care through insurance system would provide an opportunity for regulating their quality.

However, this scheme has attributes to enhance the system's efficiency by introducing capitation payments, graded incentive structure, gatekeeper function, and purchaser-provider split. Moreover, if the system drives up demand for necessary care which was earlier not availed due to financial catastrophic effects, the system merits introduction on efficiency grounds. Second, the proposed scheme draws revenue from direct general tax, subsidizes socially and economically disadvantaged groups, and exempts the latter groups from demand-side cost sharing, which make the scheme equitable. Third, it offers opportunity to improve quality of private and the public sector through accreditation system. Finally, the scheme has a potential to strengthen the public healthcare system by a carefully designed incentive system for public sector providers and improving infrastructure.

Acknowledgment

The article is a modified version of an essay written by the lead author during his MSc in Health Policy, Planning and Financing at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK, during 2008-2009. I am grateful to Prof. Anne Mills, Dr. Kara Hanson, Dr. Dirk Mueller, and Dr. Fern Terris-Pressholdt who taught during the Economic Analysis for Health Policy module.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Peters DH, Rao SK, Fryatt R. Lumping and splitting: The health policy agenda in India. Health Policy Plan. 2003;18:249–60. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czg031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berman P, Ahuja R, Tandon A, Sparkes S, Gottret P. Government Health Financing in India: Challenges in Achieving Ambitious Goals. Washington, DC: World Bank Human Nutrition and Population; Discussion Paper 598862010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters D, Yazbeck A, Ramana G, Pritchett L, Wagstaff A. Better Health Systems for India's Poor. New Delhi: The World Bank; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Report - Health systems: improving performance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Accounts India 2004-05. New Delhi: National Health Accounts Cell, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2009. MOHFW. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar AS, Chen LC, Choudhury M, Ganju S, Mahajan V, Sinha A, et al. Financing health care for all: Challenges and opportunities. Lancet. 2011;377:668–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61884-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Doorslaer E, O’Donnell O, Rannan-Eliya RP, Somanathan A, Adhikari SR, Garg CC, et al. Effect of payments for health care on poverty estimates in 11 countries in Asia: An analysis of household survey data. Lancet. 2006;368:1357–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serrao A, Sujatha B. Birth Registration A Background Note. Bangalore: Community Devlopment Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morbidity, Health Care and the Condition of the Aged. New Delhi: National Sample Survey Organization, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation; 2006. NSSO. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prabhu KS, Selvaraju V. Public financing for health security in India: Issues and Trends. In: Prasad S, Sathyamala C, editors. Securing Health for All: Dimensions and Challenges. 1st ed. New Delhi: Institute for Human Development; 2006. pp. 410–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mossialos E, Dixon A. Funding Health Care in Europe: Weighing up the Options. In: Mossialos E, Dixon A, Figueras J, Kutzin J, editors. Funding health care: options for Europe. Buckingham: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Family health Survey 3. Mumbai: International Institute of Population Sciences and ORG Macro; 2006. IIPS. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Report of the Working Group on Health Care Financing including Health Insurance for the 11th Five Year Plan. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; [20th January, 2011]. MOHFW. Accessed from http://planningcommission.nic.in/aboutus/committee/wrkgrp11/wg11_rphfw3.pdf. on . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority Bill, 1999. New Delhi: Government of India; 1999. IRDA. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folland S, Goodman A, Stano M. The Economics of Health and Health Care. 6th ed. New York: Prentice Hall Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arrow K. Uncertainty and welfare economics of medical care. Am Econ Rev. 1963;53:941–73. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akerlof G. The markets for “Lemons”: Quality uncertainty and market mechanism. Quart J Econ. 1970;84:488–500. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chollet D, Lewis M. Private Insurance: Principles and Practice. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreiro A. An Overview of the Chilean Private Health Insurance System and Some Useful Lessons for the Current Indian Debate. Santiago: Office of the Superintendent of ISAPRES; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medici A, Londono J, Coelho A, Sexenian H. Managed Care and Managed Competition in Latin America and the Carribean. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahal A. Assessing Private Health Insurance in India: Potential Impacts and Regulatory Issues. Econ Political Weekly. 2002;37:559–71. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhat R, Babu SK. Health insurance and third party administrators: Issues and challenges. Econ Political Weekly. 2004;39:3149–59. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellis R, Alam M, Gupta I. Health insurance in India: Prognosis and prospects. Econ Political Weekly. 2000;35:207–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Users perceptions on existing facilities in Delhi Administrative hospitals and Central Government Hospitals of Delhi. New Delhi: National Council of Applied Economic Research; 1993. NCAER. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsaio W. Unmet health needs of 2 billion: Is community financing a solution. Washington DC: World Bank; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranson MK. Health insurance in India. Lancet. 2001;358:1555–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06614-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devdasan N, Ranson K, Van Damme W, Acharya A, Criel B. The landscape of community health insurance in India: An overview based on 10 case studies. Health Policy. 2006;78:224–34. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Social Security Report 2010/11: Providing coverage in times of crisis and beyond. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2010. ILO. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranson MK. Community-based health insurance schemes in India: A review. Nat Med J India. 2003;16:79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devadasan N, Ranson K, van Damme W, Acharya A, Criel B. The landscape of community health insurance in India: An overview based on 10 case studies. Health Policy. 2006;78:224–34. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acharya A, Ranson K. Health Care Financing for the Poor Community-based Health Insurance Schemes in Gujarat. Econ Political Weekly. 2005;40:4141–50. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devadasan N, Ranson K, van Damme W, Acharya A, Criel B. Community health insurance in India: An overview. Econ Political Weekly. 2004;39:3179–83. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagstaff A. Research Working Paper No. 4150. Washington, DC: World Bank; An impact evaluation of China's new cooperative medical scheme. Available from: http://ssrn.com/abstract 5965078.2007 . [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preker A. Geneva: Commission on Macroeconomics and Health; Health care financing for rural and low-income populations: The role of communities in resource mobilization and risk sharing. (Synthesis background report to Commission on Macroeconomics and Health) Available from: http://www.cmhealth.org/wg3.htm.2001 . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ekman B. Community-based health insurance in low-income countries: A systematic review of the evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:249–70. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aggarwal A. Impact evaluation of India's ‘Yeshasvini’ community-based health insurance programme. Health Econ. 2010;19(Suppl):5–35. doi: 10.1002/hec.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahal A, Rajaraman I. Decentralisation, preference diversity and public spending: Health and education in India. Econ and Political Weekly. 2010;43:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gwatkin DR, Ergo A. Universal health coverage: Friend or foe of health equity? Lancet. 2011;377:2160–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Report 2005 Making every mother and child count. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhat R, Singh A, Maheshwari S, Saha S. Maternal health financing-issues and options a study of chiranjeevi yojana in Gujarat. Ahmedabad: Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pannarunothai S, Mills A. The poor pay more: Health-related inequality in Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1781–90. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Research, evaluation and policy. In: Buse K, Mays N, Walt G, editors. Making Health Policy. London: OUP; 2008. pp. 157–61. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tancharoensathien V, Prakonsai P, Limwattananon S. Paper prepared for the Health Systems Knowledge Network of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO; 2006. Achieving universal coverage in Thailand: what lessons do we learn? [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Rural Health Mission: Implemenatation Guidelines. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005. MOHFW. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahal A, Fan V. Achieving Universal health Coverage in India: An Assessment of the Policy Challenge. Melbourne: Monash University School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine and Harvard School of Public Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prinja S, Bahuguna P, Pinto AD, Sharma A, Bharaj G, Kumar V, et al. Cost of universal health care provision in India: A model-based analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]