Abstract

The current study aimed to explore the public views and expectation about a successful communication process between the healthcare providers/physicians and patients in Penang Island, Malaysia. A cross-sectional study was conducted in Penang Island using a 14-item questionnaire. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 15.0® were used to analyze the collected data. A nonparametric statistics was applied; the Chi-square test was applied to measure the association among the variables. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. A total of N (500) respondents have shown willingness to participate in the study with a response rate of 83.3%. The majority 319 (63.9%) have disclosed to communicate with their healthcare providers in the Malay language and about 401 (80.4%) of the respondents were found satisfied with the information provided by the physician. It was a common expectation by the most of the sample to focus more on the patient history before prescribing any medicine. Moreover, about 60.0% of the respondents expected that the healthcare providers must show patience to the patient's queries. The level of satisfaction with the information shared by the healthcare providers was higher among the respondents with a higher education level. Furthermore, patients with higher level of education expect that physician shouldwell understand their views and medical history to prescribe a better therapeutic regimen.

Keywords: Consumer, healthcare communication, healthcare providers, satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade patient–physician communication has become an important concern in healthcare delivery and.[1,2] Nowadays, a higher emphasis is given to effective patient–physician communication. Effective communication means, “The healthcare providers must ensure that the information regarding the disease and drug are well communicated and understood by the patient as per their abilities and needs”.[3] It is evident that effective patient–physician communication ensures the optimal patient outcomes and high level of consumers satisfaction.[2,4,5] On other hand, substandard communication might be one of the factors responsible for the poor compliance level and therapeutic outcomes. It is seen that often patients feel distressed because the healthcare providers lack patient-oriented communication skills, which hinder the delivery of actual medical advice/message to the patient. In addition, empathy and kindness are other important factors that are often found deficient in the patient–physician communication session and in turn result in a major gap in communication.[6,7] It is reported that patient's emphasis on communication behavior and listening will result in a higher level of satisfaction, and such patients are found more willing to continue their treatment.[6,8] However, poor communications skill on the part of the healthcare providers will resultin a unsatisfied patient that in turn affects the quality of the treatment and compliance to therapy.[8]

It is noticed that there are some barriers that often get in the way of an ideal patient–physician communication. Sometimes the healthcare providers have a busy schedule and need to deal with many patients, which limit the duration of communication and affect the quality of session.[9] In addition, limited social skills to make the interaction with the patient are another potential barrier to an effective communication session between the patient and physician.[10,11] This shortage of time and lack of social skills hinders the affective interaction between the patient–physician and will result in a frustrated patient who understands nothing about his disease and therapy.[5] Due to the importance of communication in the healthcare and therapeutic outcomes, a high value is given to the physician communication skills. Thus, effective communication between the consumers and their healthcare providers is very crucial to ensure the patient safety and high therapeutic outcomes.[9]

Moreover, the communication process will be more challenging in multicultural country like Malaysia. The population of Malaysia is mainly comprised of three main groups: Malay, Indians, and Chinese. In addition, foreigners from different Asian and Arab region are the other groups residing in Malaysia. Malay, Tamil, Hindi, and Chinese are the commonly spoken languages by these groups. This diversity of language and culture would be a main factor that result in some barrier during the patient–physician communication.[12,13] Cultural diversity not only affects the patient–physician communication, but also affect the presentation of clinical symptoms. In a session of 15–20 min, the physician must choose appropriate words, tones, and body language to clearly convey the message to the patient.[14] Previous preliminary efforts (N=100) in the primary care clinics to evaluate the barrier to patient–physician communication among the Malaysians revealed that the lack of physician–patient understanding result in hindrance to an effective communication. It was found that a patient's low level of health literacy and inability of the physician to effectively listen the patients’ views were the main factors that may affect the communication process. However, so far there is no study conducted in the Malaysian scenario that evaluates the general public expectations with the time and level of information provided by the healthcare providers. Therefore, considering this deficiency as a motivation the current study aimed to explore the public views about a successful communication between the healthcare providers and patientsin Penang Island, Malaysia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

A cross-sectional study was designed to explore the general public views in Penang Island.

Study population

The respondents for this study were public residing in the Penang Island. Penang is one of the 13 states of Malaysia with an estimated population of 1.5 million. Mainly three main groups reside in Penang, i.e. Malay, Chinese, and Indians. In addition to these, three foreigners from other ethnicity/nations are also residing in Penang. Penang is further divided into two parts i.e. mainland and island. The study sample recruited for this study was from the Penang Island. The sample size for this study was estimated according to the population size using the online sample size calculator, i.e., Raosoft® with a confidence interval of 95% and 5% margin of error. The minimum affective sample size for the study was 377. However, due to the lack of sampling frame and up-to-date electronic population database randomized sampling was not possible. Therefore, a convenient sampling method was adopted and the number of respondents was increased to 600 in order to reduce the chances of sampling bias.

Data collection

A self-administered 14-item questionnaire was used to attain the objective of the study. Public visiting the shopping malls, food courts, and recreation areas were approached for their potential participation in this study.

Study tool

The study tool was comprised of mainly four sections.

Section one was comprised of six items. The first five items in this section has covered the demographic information while the sixth item was concerned with the respondents’ attitude toward the self-medication.

The section two mainly aims to reveal the healthcare behavior of respondents. This section consists of mainly three items. The first item in section two was an open-ended question aim to identify the language that often used during the communication session between the respondent and physician, while the second and third items were exploratory in nature. Item two explores the frequency of the visits to the healthcare providers [How often you visit your healthcare provider?] with a five-item scale, i.e. rarely, very rarely, usually, very frequently, and frequently. However, item three explore the time spared by the physician for the patient on an average visit. [How much time your healthcare provider spends with you on a routine checkup/consultation? 0–5 min, 6–10 min, 11–15 min, 16–20 min, 21–25 min, 26–30 min and more than 30 min].

Section three has explored the personal experience of the respondents in the health communication process with healthcare providers/physicians. A nominal scale was used for respondent's convenience to disclose their experience. The following two questions were the part of section three

The physician shares the details about disease and treatment in an easy and understandable manner?[Yes/No]

Will you take into consideration all the advice given to you by your healthcare providers? [Yes/No]

Section four was the last section of the study tool and was comprised of five items that were used to explore the respondents view/expectations from the healthcare providers. A five-item Likert-scale [strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree] was used to predict respondents’ views. These five items are shown as above.

The healthcare providers should bear good communication skills.

Before suggesting any treatment to me healthcare providers should first understand the patient medical history

The healthcare providers should answer the patient queries with patience.

The healthcare providers should use a language that is understandable to the patient.

The healthcare providers should allocate adequate time for consultation to the patient.

Validation of the study tool

The contents of the study tool were screened out with the advice and consultation of the professionals at Discipline of Social and Administrative Pharmacy, School of Pharmaceutical Science, University Sains Malaysia. After finalizing the contents of the tool, all the items in the four sections were translated to the Malay language using a forward-backward method. Face validity of the tool was done using a pilot study on a group of 30 respondents [The pilot sample was not included in the study sample], while to ensure the internal consistency of the tool reliability scale was applied, α values for this study tool was 0.58.

Data management and analysis

Microsoft® Excel 2007 and SPSS software version 15.0® were used to analyze the collected data. A nonparametric statistics was applied; the Chi-square test was applied to measure the association among the variables. However, Fisher's exact test was preferred over the Chi-square test in the cases when more than 25% of the cells have expected count <5. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

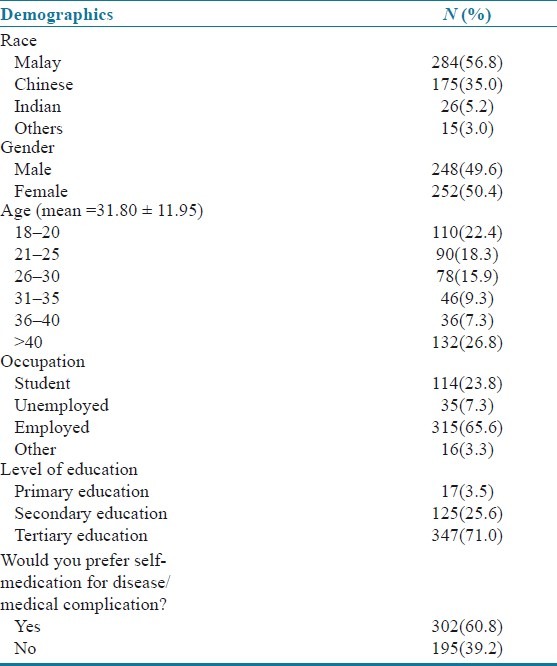

A total of N (500) respondents have shown willingness to participate in the study with a response rate of 83.3%. The majority of the respondent were Malay 284 (56.85) followed by Chinese and Indians. Most of the respondents were from the age group over 40 years. About 315 (65.6%) of the respondents were employed, and it was seen that most holds tertiary level an educational qualification 347 (71.0%). Surprisingly about 60.0% of the respondents were found favoring the self-medication. The detailed demographic information of the respondents is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information of the respondents

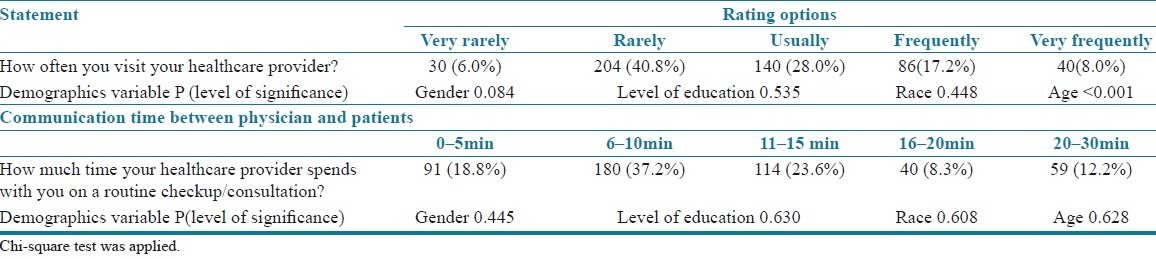

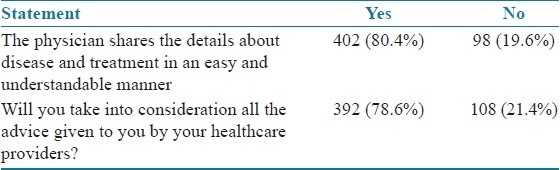

While exploring the healthcare seeking behavior it was seen that respondents frequently communicated with their healthcare providers in the Malay language [319(63.9%)], (Bahasa Malaysia) followed by the English [156(31.3%)], and Chinese [103(20.6%)]. About 60.0% of the respondents have disclosed that they usually/frequently visit their healthcare providers. It is seen that the respondents aged over 40 years were more likely (P≤0.001) to visit their physicians and in most of the cases the average length of the communication session 6–15 min [Table 2]. In terms of the level of satisfaction with the information provided by the physician during the communication session, about 401 (80.4%) of the respondents were found satisfied and about 392 (78.6%) take in consideration all the advice given by the physician [Table 3].

Table 2.

Healthcare seeking behavior of the respondents

Table 3.

Respondents’ personal experience in health communicative process with healthcare providers

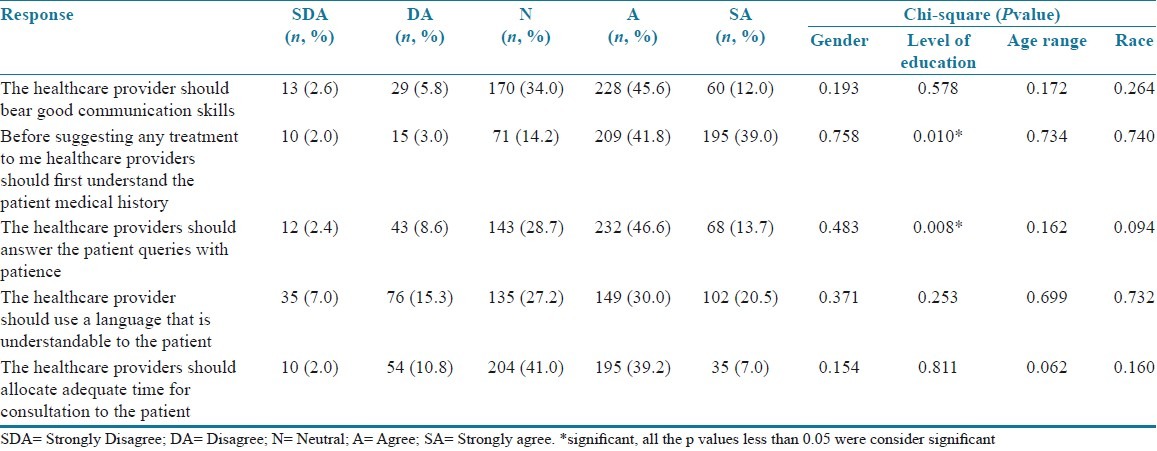

The last section of the questionnaire has focused on the respondent's expectation from the healthcare providers during the communication session. The majority expected the healthcare providers to focus more on the patient history before prescribing any medicine. Moreover, about 60.0% of the respondents expected that the healthcare providers must show patience to the patient's queries. Further details on this particular section are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Respondents expectations from the communication process

DISCUSSION

Patient satisfaction toward the communication session with the healthcare provider is considered as the vital element in the therapeutic outcome and adherence to the therapy. A satisfied patient is seems to be more challenging in the multicultural environment like Malaysia. However, the findings of the current study has shown that about 80.0% of the respondents were satisfied with the communication session and the information provided by the physician. These findings are somehow in contradiction with the findings of other studies that reported a low level of satisfaction among the patients/respondents with a higher educational profile.[15] In addition to the education profile of the respondents, language can be another possible factor resulting in a higher satisfaction level. In the majority of the cases, the communication was made in the Malay language, which can be another reason that has elevated the respondents’ level of satisfaction.[14,16] However, it was surprising to see that about 392 (78.6%) of the respondents have disclosed that they follow the physician advice but still 302 (60.8%) of the respondents were found inclined to self-medicate themselves.

While evaluating the expectation of the respondents from the healthcare providers nearly 80.0% agreed to get a prescription after evaluating the medical history and about 60.0% expect the physician to listen the patient with patience. The education level was the only factor that found significantly associated with the expectation of the respondents.[17] It is genuine for a patient to expect this from a healthcare provider because failure in doing so will generate a situation of uncertainty for the patients and he/she will be less willing to follow the physician advice.[5] Particularly discussing the level of satisfaction and expectation from the healthcare provider, it will not be wrong to state that the respondents with a higher education level expect more information concerning their disease and drug. On other hand, it will a lot easier for a physician to communicate with a patient with a higher educational background than those with a low education profile or illiterate.[10] Thus, it can be assumed that the education level helps the physician to know what information patient is seeking and can reduce the chance of miscommunication/misunderstandings during the diagnosis.[16] Therefore, the responsibility for a satisfied patient mainly lay on the physician shoulder; the patient silence does not mean that he/she understood all what was communicate by the healthcare providers.[18] In other words, a healthcare provider should possess good judgmental and communication skills. Lack of these skills on the part of healthcare providers will result in an unsatisfied patient with a low recovery rate and compliance to therapy.[16–19] The second most disclosed expectation of the respondents was “the physician aptitude to listen the patient views”. For effective discussion, the participation of both healthcare providers and patients is essential. It is reported that physicians often dominate in the discussion/consultation session[19,20,21] and in the end, they are confident that patient is satisfied[4,22] and communication was successful. However, the truth is different from their suppositions when a patient complained that their healthcare providers were always impatient and a very short time was given by the physician to listen their views.[10] For a communication session, it will be more effective if the physician develops the empathy to understand the medical and emotional needs of the patients, by doing so will be helpful in resulting a satisfied patient that is more complaint with his/her therapy.[23]

LIMITATIONS

A convenient sample can be seen as a main limitation of this study. The majority of the respondents were with a tertiary education level. Therefore, the finding of the current study will not be representative of the patients/public with low educational background. Furthermore, the current study is unable to identify the type disorders that were self-medicated by the respondents. Moreover, in addition to a higher education level, it may be possible that the respondents were more knowledge about their disease, which not only gives them the confidence to self-medicate themselves but also results in a higher level of satisfaction from the patient consultation. Future studies should consider these issues while further exploring the different aspects of communication sessions between the patient and the healthcare provider.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the current study reflected that the level of satisfaction with the physician communication was greater among the respondents with the tertiary/higher education level. It can be assumed that the patients’ education is the main factor affecting the respondents’ expectations from a physician to well understand their views and medical history to prescribe a better therapeutic regimen.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parrot R. Emphasizing “Communication” in health communication. J Commun. 2004;54:751–87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A Review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hugman B. Healthcare Communication. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JB, Boles M, Mullooly JP, Levinson W. Effect of clinician communication skills training on patient satisfaction: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:822–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-11-199912070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andaleeb SS. Service quality perceptions and patient satisfaction: A study of hospitals in developing country. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1359–70. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wanzer MB, Booth-Butterfield, Grubber K. Perceptions of health care providers’ communication: Relationship between patient-centered communication and satisfaction. Health Commun. 2009;16:363–84. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1603_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centered care: The patient should be the judge of patient centered care. BMJ. 2001;322:444–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lochman JE. Factors related to patients satisfaction with their medical care. J Health Commun. 1983;9:91–109. doi: 10.1007/BF01349873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steelnwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of come, and concordance of patient and physicians race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrera-Kiengelher L, Villamil-Álvarez M, Pelcastre-Villafuerte B, Cano-Valle F, López-Cervantes M. Relationship between health providers and patients in Mexico City. Rev SaúdeOública. 2009;43:589–94. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102009005000042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baalbaki I, Ahmed ZU, Pashtenko VH, Makarem S. Patient satisfaction with healthcare delivery systems. Int J Pharm Healthc Mark. 2008;2:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O., 2nd Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kundhal KK, Kundhal PS. MS Cultural diversity: An evolving challenge to physician-patient communication. JAMA. 2003;289:94. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan TM, Hassali MA, Al-Haddad M. Patient-physician communication barrier: A pilot study evaluating patient experiences. J Young Pharm. 2011;3:250–5. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.83778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margolis SA, Al-Marzouqi S, Revel T, Reed RL. Patient satisfaction with primary healthcare service in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:241–9. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jangland E, Gunningberg L, Carlsson M. Patients’ and relatives’ complaints about encounters and communication in health care: Evidence for quality improvement. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adamson TE, Tschann JM, Gullion DS, Oppenberg AA. Physician communication skills and malpractice claims-A complex relationship. West J Med. 1989;150:356–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman-Stewarta D, Brundagea MD, Tishelman C. A conceptual framework for patient-professional communication: An application to the cancer context. Psychooncology. 2005;14:801–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckett MK, Elliott MN, Richardson A, Mangione-Smith R. Outpatient satisfaction: The role of nominal versus perceived communication. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:1735–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevenson FA, Cox K, Britten N, Dundar Y. A systematic review of the research on communication between patients and health care professionals about medicines: The consequences for concordance. Health Expect. 2004;7:235–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gopinath B, Radhakrishnan K, Sarma PS, Jayachandran D, Alexander A. A questionnaire survey about doctor-patient communication, compliance and locus of control among South Indian people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2000;39:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(99)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redfern J, Menzies M, Briffa T, Freedman SB. Impact of medical consultation frequency on modifiable risk factors and medications at 12 months after acute coronary syndrome in the CHOICE randomized controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2010;145:481–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277:678–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]