Abstract

Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type Z (Ptprz) is widely expressed in the mammalian central nervous system and has been suggested to regulate oligodendrocyte survival and differentiation. We investigated the role of Ptprz in oligodendrocyte remyelination after acute, toxin-induced demyelination in Ptprz null mice. We found neither obvious impairment in the recruitment of oligodendrocyte precursor cells, astrocytes, or reactive microglia/macrophage to lesions nor a failure for oligodendrocyte precursor cells to differentiate and remyelinate axons at the lesions. However, we observed an unexpected increase in the number of dystrophic axons by 3 days after demyelination, followed by prominent Wallerian degeneration by 21 days in the Ptprz-deficient mice. Moreover, quantitative gait analysis revealed a deficit of locomotor behavior in the mutant mice, suggesting increased vulnerability to axonal injury. We propose that Ptprz is necessary to maintain central nervous system axonal integrity in a demyelinating environment and may be an important target of axonal protection in inflammatory demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and periventricular leukomalacia.

Remyelination after myelin breakdown that occurs in demyelinating disease, such as multiple sclerosis, restores function and protects axons, whereas its failure is associated with the axonal loss that accounts for irreversible deterioration in multiple sclerosis.1,2 Identifying pathways critically involved in remyelination is fundamental to the development of regenerative therapies that are currently missing in the treatment of demyelinating diseases.3 Protein tyrosine phosphatases are a diverse group of enzymes that, together with protein tyrosine kinases, regulate tyrosine phosphorylation and hence coordinate intracellular signaling responses. Protein receptor tyrosine phosphatase type Z (Ptprz; alias receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase β) is widely expressed by both neurons and glia in the developing and adult nervous system and has been implicated in neuronal migration, morphogenesis, synapse formation, and paranode formation.4–8

Ptprz is also expressed in oligodendrocyte lineage cells and has been suggested to play a key role in oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination.9–11 However, mice deficient in Ptprz do not display obvious behavioral phenotype, and their CNS development, including myelination, appears grossly normal.12 By contrast, when subject to immune-mediated demyelination by experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), Ptprz-deficient mice exhibit sustained paralysis and poor functional recovery. In the spinal cords of these mice, widespread apoptosis of oligodendrocytes has been observed, suggesting that Ptprz may influence functional recovery from demyelination by promoting oligodendrocyte survival.13

We analyzed CNS remyelination in Ptprz-deficient mice using a simple toxin–based model of demyelination to avoid the ambiguities of interpretation implicit in immune-mediated models, such as EAE. We induced demyelination by injecting 1.0% lysolecithin into the spinal cord ventral funiculus, which results in a lesion of focal primary demyelination with relative preservation of axons.14 Unexpectedly, we observed extensive axonal loss and Wallerian degeneration after lysolecithin injection in the Ptprz null mice compared with wild-type (WT) mice. This result, although shedding little light on the role of Ptprz in remyelination, reveals an unexpected role of this protein in protecting axons that have undergone primary demyelination and therefore identifies it as a potential and exciting novel target for neuroprotection in demyelinating disease.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Ptprz-deficient mice (Ptprz−/−) were generated as described previously.15 Briefly, the carbonic anhydrase and fibronectin type III domains were replaced with the LacZ reporter gene followed by 3 stop codons. WT littermates (Ptprz+/+) were used as controls.

Surgery

All the surgical procedures were performed under a UK Home Office Project license. Focal demyelination was induced by injecting of 1.0% lysolecithin (Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd, Dorset, UK) in saline into the spinal cord ventral funiculus of Ptprz null mice (Ptprz−/−) or WT littermates (Ptprz+/+). CatWalk gait analysis was performed as described previously.16 The animals were sacrificed at 3, 5, 10, and 21 days after surgery for analysis.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Mice (n = 10 per group per survival time) were perfused with 4.0% paraformaldehyde. Tissues were kept 3 hours in the fixative, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose, and frozen in isopentane. Sections (12 μm thick) were cut in a cryostat and kept at −80°C until use. For immunofluorescence, the sections were dried and washed in PBS with 0.3% of Triton. After blocking with normal donkey serum, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-Olig2 (1:1000; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and rabbit anti-NF200 (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) overnight at 4°C. For mouse anti-APC/CC1 (Ab-7) (1:300; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) and mouse anti-amyloid precursor protein (APP) (clone 22C11) (1:400; Millipore) immunostaining, antigen retrieval (Dako Real Target Retrieval Solution; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and mouse on mouse blocking (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) were performed according to manufacturer instructions before antibody incubation. For cell death analysis, TUNEL staining was performed using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, POD (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), according to instruction before primary antibody incubation. After 2 washes in 1× PBS, the sections were incubated with secondary antibody: Donkey (Dk) anti-mouse Cy2, Dk anti-rabbit Cy3, Dk anti-rat Cy3 (all from Jackson Immunoresearch Europe Ltd, Suffolk, UK), and Dk anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). The sections were observed in an Axio Observer microscope (Carl Zeiss, Peabody, MA).

Electron Microscopy

Animals for resin embedding (n = 10 per group) were perfused with 2.0% glutaraldehyde (pH 7.4). The spinal cords were dissected, and segments were left in the same fixative overnight at 4°C. Tissues were postfixed in 2.0% of osmium tetroxide (Oxkem Limited, Reading, UK) and embedded in resin (TAAB Labs, Aldermaston, UK). Sections (1 μm thick) were cut on a Leica (Milton Keynes, UK) RM2065 ultramicrotome and stained with 1% toluidine blue. Ultr-thin resin sections were observed at Hitachi (Maidenhead, UK) H-600 electron microscope.

Quantitation and Analysis

Images were photographed with an Axio Observed microscope (Carl Zeiss). Images were taken at 20× or 40× magnification. Positive cells were counted and expressed per area. Six animals were used for each group, and 3 sections of each animal were counted. The area was calculated using Axiovision software version 4.7.1 (Carl Zeiss). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by a post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison test and unpaired t-test. The data were analyzed using Prism GraphPad program version 5.0b (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant between samples.

Results

Ptprz Loss Does Not Influence OPC Recruitment or Differentiation After Spinal Cord Demyelination

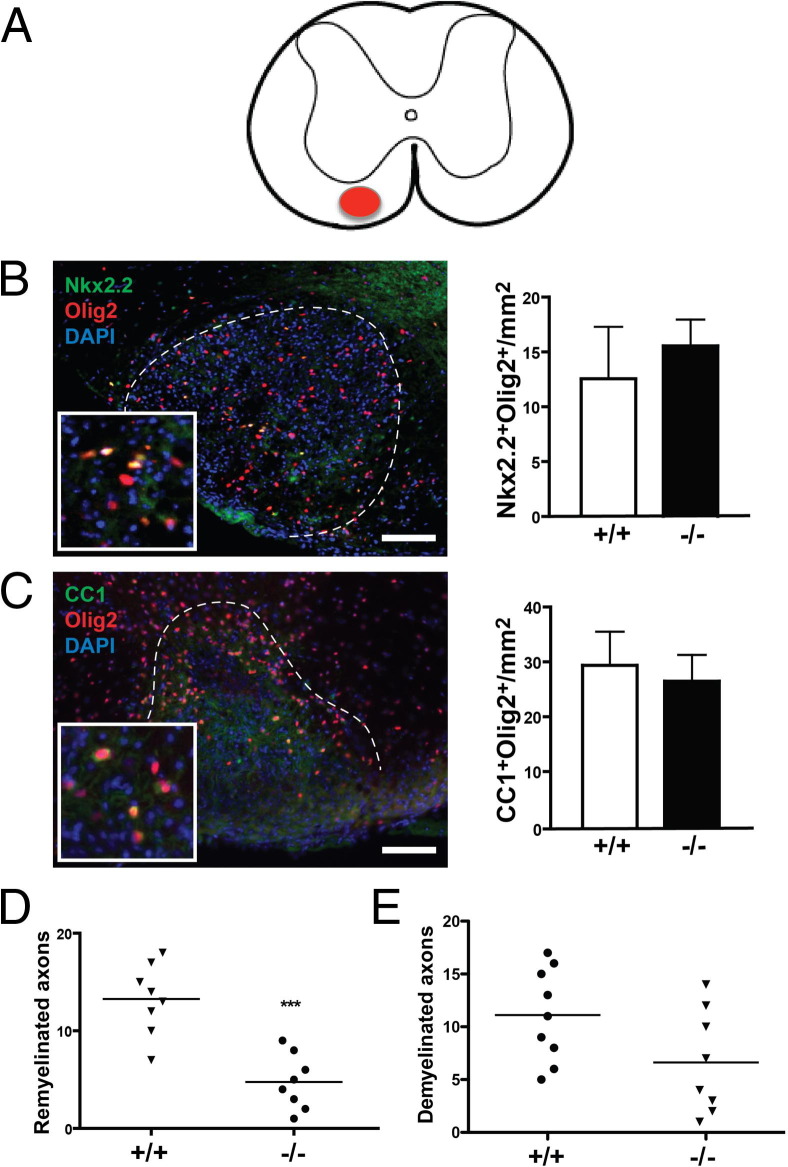

To determine whether Ptprz plays a role in oligodendrocyte precursor cell (OPC) recruitment or differentiation, focal demyelination was produced by lysolecithin injection into the left spinal cord ventral funiculus of Ptprz−/− mice and Ptprz+/+ littermates (Figure 1A). Immunostaining analysis was performed on spinal cord sections 10 and 21 days post lesion (dpl). We used Nkx2.2 as a marker of recruited OPCs, CC1 as a marker of mature oligodendrocytes, and Olig2 as a pan-oligodendrocyte lineage marker.17 At 10 dpl, many OPCs co-labeled with Nkx2.2 and Olig2 were observed in spinal cord lesions, but we detected no significant difference in the number of precursor cells between the two groups (Figure 1B). At 21 dpl, oligodendrocytes co-labeled with CC1 and Olig2 were observed in spinal cord lesions, but again we found no significant difference in the density of mature oligodendrocytes between the two groups (Figure 1C). These results suggest that Ptprz was neither required for OPC recruitment nor oligodendrocyte differentiation after demyelination.

Figure 1.

Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell recruitment and remyelination are not impaired after lesion. A: Illustration of a transverse spinal cord section with a focal lesion in the left ventral funiculus. B: A focal lesion from a Ptprz−/− mouse at 10 dpl immunostained with anti-Nkx2.2, anti-Olig2, and DAPI. Ventral funiculus lesion can be observed within the dashed line. Inset: Nkx2.2+Olig2+ and Nkx2.2−Olig2+ cells. Nkx2.2 and Olig2 are both detected in nuclei. Quantitation of Nkx2.2+Olig2+ OPCs at the lesion reveals no significant difference between Ptprz−/− mice and control mice. C: A focal lesion from a Ptprz−/− mouse at 21 dpl immunostained with anti-CC1, anti-Olig2, and DAPI. Inset: CC1+Olig2+ and CC1−Olig2+ cells. CC1 displays cytoplasmic distribution. Quantitation of CC1+Olig2+ oligodendrocytes reveals no significant difference between the two groups. D: Ranking analysis on the extent of remyelination at 21 dpl reveals less remyelination in Ptprz−/− mice compared with WT siblings. E: Ranking analysis of the extent of demyelination at 21 dpl reveals no difference between the 2 groups. Scale bar = 100 μm. Mean ± SEM are shown. ***P < 0.001, U-test.

Ptprz−/− Mice Exhibit Significant Axonal Loss After Demyelination

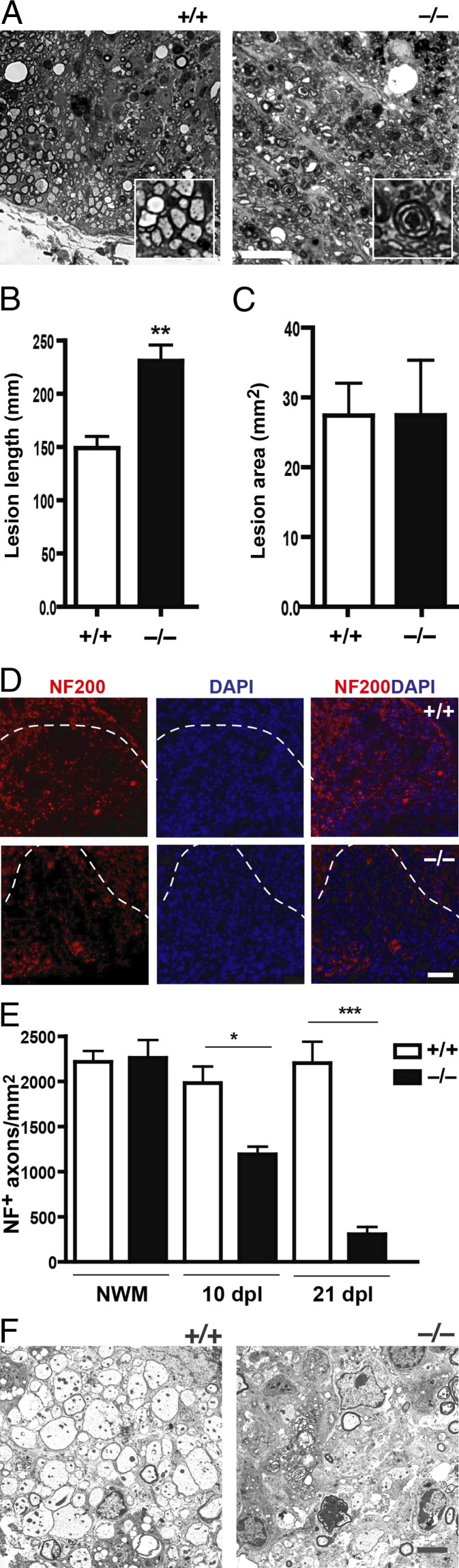

We next performed morphologic analysis of transverse semithin resin sections of spinal cords at 21 dpl, when remyelination is expected to be near completion, to determine whether there was a difference in the extent of remyelination between Ptprz−/− and Ptprz+/+ mice. Analysis of control littermates revealed a pattern and extent of remyelination consistent with previously reported studies. However, we found that Ptprz−/− mice appeared to display relatively fewer remyelinated axons in the lesions. When lesions were ranked blindly for the extent of remyelination, we found a significant difference between the two groups (Figure 1D). This finding suggested that many axons might not have been remyelinated in the Ptprz−/− mice, and if so, the mutant mice would be expected to have more demyelinated axons in the lesions compared with controls. However, when ranking analysis was performed for histologically identifiable demyelinated axons in the lesions, we found no significant difference between the knockout and control groups (Figure 1E). A possible explanation for the puzzling observation was that there were fewer intact axons in the lesions of Ptprz−/− mice at 21 dpl, and thus fewer axons were remyelinated, which would account for the CC1+ cell density remaining unchanged despite less remyelination. Consistent with this hypothesis, we also detected many dark-staining foci of disrupted myelin, indicative of Wallerian degeneration in the lesions of Ptprz−/− mice, which is a feature rarely detected in Ptprz+/+ controls (Figure 2A). This unexpected observation suggested that many CNS axons might have degenerated by 21 dpl in the absence of Ptprz expression.

Figure 2.

Demyelination results in increased axon loss. A: A spinal cord section from Ptprz+/+ and Ptprz−/− mice at 21 dpl. The control mouse exhibits many remyelinated axons. Inset: A group of remyelinated axons. Ptprz−/− mouse displays dark, disorganized myelin whorls indicative of Wallerian degeneration, which is rarely observed in control. Inset: An axon undergoing Wallerian degeneration. Scale bar = 20 μm. B: Quantitation of lesion lengths at 21 dpl reveals significantly greater longitudinal lesion in Ptprz−/− mice compared with control. C: Quantitation of transverse section of lesion at 21 dpl reveals no difference between Ptprz−/− and control animals. **P < 0.005, unpaired t-test. D: Spinal cord sections of Ptprz−/− and Ptprz+/+ mice at 21 dpl were immunostained with anti-NF200 and DAPI. The lesion is detectable under the dashed line. NF200+ axons at the lesion are visibly less in the Ptprz−/− mice. Scale bar = 50 μm. E: Quantitation of NF200+ axons in the non-lesioned white matter (NWM) reveals no difference between Ptprz−/− and control mice. However, quantitation of axons in lesions reveals significantly fewer axons in Ptprz−/− mice compared with controls. F: Ultrastructure image of a spinal cord section at 10 dpl from a Ptprz+/+ mouse reveals well-preserved, intact demyelinated axons. The Ptprz−/− mouse displays fewer intact demyelinated axons within the lesion. Mean ± SEM are shown. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0001 one-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison test.

A measurement of the extent of spinal cord lesions between Ptprz−/− and control animals revealed that the longitudinal length of the lesions was at least several hundred micrometers longer in mice lacking Ptprz compared with control animals (Figure 2B). Moreover, the transverse widths of the lesions were similar to each other in the 2 groups (Figure 2C), consistent with the volume and concentration of lysolecithin delivered to the ventral spinal cord being the same in the 2 groups. These observations further indicate that by 21 dpl, many descending (ventrolateral) axons were undergoing distal degeneration in the Ptprz−/−mice.

To examine the extent of axon preservation in the lesion, we labeled axons with antibodies against neurofilament (NF200) (Figure 2D). In nonlesioned white matter, we found no significant difference in the number of NF200+ axons between Ptprz−/− and control animals (Figure 2E). However, the density of total NF200+ axons decreased by >25% at 10 dpl in the lesions of Ptprz−/− mice compared with controls and decreased even further by up to 75% at 21 dpl. This observation suggests that many axons might have degenerated shortly after lysolecithin injection. Indeed, electron microscopic examination of resin embedded sections revealed fewer intact axons in the lesions of Ptprz−/− mice compared with controls (Figure 2F).

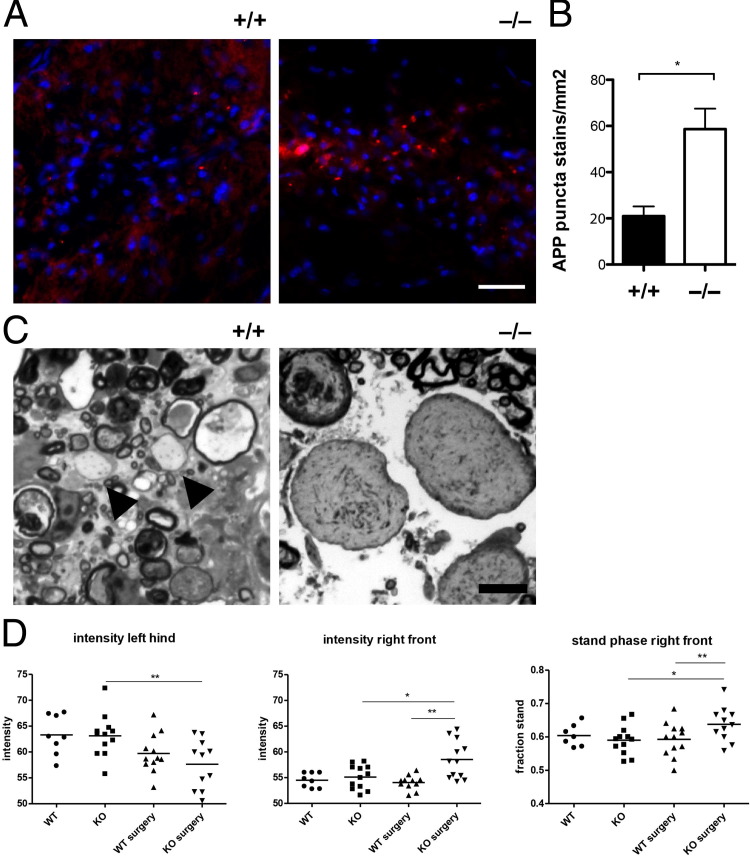

CNS Axons of Ptprz−/− Mice Become Dystrophic Shortly After Injury

To determine whether axonal abnormality in Ptprz−/− mice could be detected in the lesions before degeneration, we performed immunostaining analysis on transverse spinal cord sections 3 dpl for the accumulated expression of APPs as an indicator of potential disturbance in axonal transport.18,19 We found that APP displayed a strikingly punctate staining pattern in lesions that rarely overlapped with TuJ1 in both analyzed groups. However, we observed that mice lacking Ptprz displayed more APP+ punctate staining in the lesions when compared with controls (Figure 3A). Quantification revealed that Ptprz−/− displayed nearly threefold more APP+ punctate stains in the lesions compared with controls (Figure 3B). Moreover, swollen axons displaying abnormal-appearing organelles were readily detectable under light microscopy examination of resin embedded sections at 3 dpl in Ptprz−/− mice compared with controls (Figure 3C). These results indicate that in the absence of Ptprz, CNS axons became dystrophic after lysolecithin injection and were vulnerable to degeneration. Next, to determine whether behavioral deficit as result of acute axonal injury could be detected, we subjected the Ptprz mouse mutants to CatWalk gait analysis at 5 dpl (Figure 3D). CatWalk is an automated system that uses video camera technology to capture and analyze the intensity and duration of paw contacts on a motion sensitive glass plate during locomotion.16,20 We found that the lesioned Ptprz−/− mice, when compared with lesioned WT siblings, displayed a significant decrease in contact intensity in their left hind limb, corresponding to axonal injuries in the left ventral funiculus where lysolecithin was injected. Moreover, the lesioned Ptprz−/− mice also displayed increased contact intensity and duration in their right front paw when compared with controls, indicative of behavioral compensation by the right front paw to deficits in the left hind limb. The observed locomotor behavioral deficits suggest that acute axonal injury in the descending ventral lateral pathways was apparent by 5 dpl. Moreover, this behavioral deficit was not inherent to Ptprz loss of function in development because the nonlesioned Ptprz−/− mice did not exhibit locomotor abnormality and displayed similar paw contact intensity and duration to the nonlesioned WT siblings.

Figure 3.

Axonal injury is detectable shortly after lesion. A: Spinal cord sections at 3 dpl were immunostained with anti-APP and DAPI. Ptprz−/− spinal cord sections displayed more punctate APP staining in lesions compared with Ptprz+/+ sections. Scale bar = 50 μm. B: Quantification reveals a significant increase in the number of APP punctate stains in the lesions of Ptprz−/− mice compared with WT mice at 3 dpl. C: Semithin resin sections stained with toluidine blue. Compared with the control (Ptprz+/+) section, which displays demyelinated axons (arrowheads), the Ptprz−/− section displays abnormally swollen and dystrophic axons containing abnormal cytoskeletal densities or organelles. Scale bar = 5 μm. D: CatWalk gait analysis at 5 dpl reveals significantly decreased paw intensity in the left hind limb of the lesioned Ptprz−/− mice (knockout surgery) compared with controls. Increased right front paw intensity and stand phase (duration) were also detected in the lesioned Ptprz−/− mice. Mean ± SEM are shown. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 unpaired t-test.

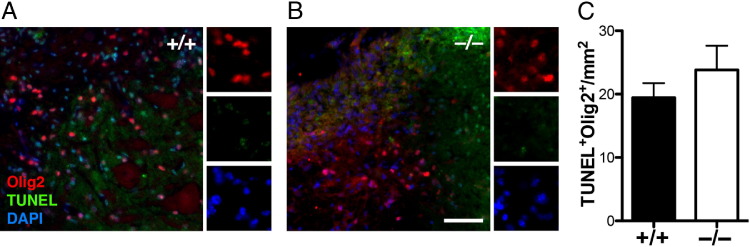

Analysis of Oligodendrocyte Apoptosis in Ptprz−/− Mouse Spinal Cord Lesions

Ptprz has previously been suggested to mediate functional recovery from immune-mediated demyelination after EAE induction via regulating oligodendrocyte survival.13 To determine whether Ptprz is required for oligodendrocyte survival in focal lysolecithin-induced demyelination, we analyzed the extent of apoptosis in spinal cord sections of Ptprz−/− mice at 21 dpl. In situ cell death detection by TUNEL staining followed by immunolabeling with anti-Olig2 for oligodendrocyte lineage cells were performed. We observed many TUNEL staining in the core of demyelinated lesions in WT (Figure 4A) and Ptprz −/− mice (Figure 4B). However, these apoptotic cells rarely co-labeled with Olig2+ oligodendrocyte lineage cells in either the WT or Ptprz−/− mice (Figure 4C), suggesting that Ptprz is not required for oligodendrocyte survival after lysolecithin-induced demyelination.

Figure 4.

Oligodendrocytes do not undergo significant apoptosis in the lesion. In situ cell death assay was performed followed by immunostaining with anti-Olig2. Co-labeling of Olig2 and TUNEL staining was rarely detected in the lesions of WT (A) and Ptprz−/− (B) mice. Scale bar = 50 μm. C: Quantification of TUNEL+Olig2+ cells in lesions (unpaired t-test).

Discussion

In this study, we found that Ptprz does not play a significant role in oligodendrocyte survival, differentiation, or remyelination after acute lysolecithin-induced demyelination but that its expression appears to be required for axonal integrity and survival. We found that the loss of axons correlated with the acute deficit of motor behavior in the lesioned Ptprz−/− mice. The axonal degeneration observed in the Ptprz−/− mice resembles Wallerian degeneration when compared with the Ptprz+/+ mice, which exhibited a picture consistent with primary demyelination. Therefore, the lack of Ptprz makes axons more vulnerable when a demyelinating agent is injected into the spinal cord white matter tract. Induction of Ptprz mRNA in areas of axonal sprouting and glial scarring after CNS injury, implying that cell adhesion molecules and the extracellular matrix proteins to which these receptors bind to may be involved in axonal injury responses21,22 and linking Ptprz with axonal protection.

It remains unclear why under immune-mediated demyelination an increase in oligodendrocyte apoptosis would occur as described previously,13 but this increase may indicate a fundamental difference in how CNS cells respond under different injury conditions. However, the inherent ambiguity of EAE, such as i) the difficulty to predict and track the locations of demyelination; ii) the variability in the degree of inflammation, which can result either in demyelination or axonal transections; and iii) the added complexity of the adaptive immune system, may limit the analysis of regenerative or survival mechanisms intrinsic to OPCs. A possible explanation for the increased oligodendrocyte apoptosis found in EAE-induced Ptprz−/− mice may be that oligodendrocytes undergo death as result of a secondary injury process to Wallerian degeneration and that the loss of axons contributed to the impaired functional recovery from EAE.23,24 In support of this possibility, prominent Wallerian degeneration was indeed observed in EAE-induced Ptprz−/− mice.13 In conclusion, we propose Ptprz is critically involved in the maintenance of axonal integrity. Thus, Ptprz could represent a key gene in maintaining axonal integrity after CNS injury.

Footnotes

Supported by the UK Multiple Sclerosis Society (R.J.M.F.), Merck Serono, and a Du Pré Grant of the Multiple Sclerosis International Federation (C.C.F).

J.K.H. and C.C.F. contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Trapp B.D., Nave K.-A. Multiple sclerosis: an immune or neurodegenerative disorder. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin R.J.M., Ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: from biology to therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:839–855. doi: 10.1038/nrn2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang J.K., Franklin R.J.M. Regenerative medicine in multiple sclerosis: identifying pharmacological targets of adult neural stem cell differentiation. Neurochem Int. 2011;59:329–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peles E., Nativ M., Lustig M., Grumet M., Schilling J., Martinez R., Plowman G.D., Schlessinger J. Identification of a novel contactin-associated transmembrane receptor with multiple domains implicated in protein-protein interactions. EMBO J. 1997;16:978–988. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson K.G., Van Vactor D. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases in nervous system development. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1–24. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohyama K., Ikeda E., Kawamura K., Maeda N., Noda M. Receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase zeta/RPTP beta is expressed on tangentially aligned neurons in early mouse neocortex. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;148:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi N., Oohira A., Miyata S. Synaptic localization of receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase zeta/beta in the cerebral and hippocampal neurons of adult rats. Brain Res. 2005;1050:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klausmeyer A., Garwood J., Faissner A. Differential expression of phosphacan/RPTPbeta isoforms in the developing mouse visual system. J Comp Neurol. 2007;504:659–679. doi: 10.1002/cne.21479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranjan M., Hudson L.D. Regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation and protein tyrosine phosphatases during oligodendrocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;7:404–418. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sim F.J., Lang J.K., Waldau B., Roy N.S., Schwartz T.E., Pilcher W.H., Chandross K.J., Natesan S., Merrill J.E., Goldman S.A., Goldmanm S.A. Complementary patterns of gene expression by human oligodendrocyte progenitors and their environment predict determinants of progenitor maintenance and differentiation. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:763–779. doi: 10.1002/ana.20812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamprianou S., Chatzopoulou E., Thomas J.-L., Bouyain S., Harroch S. A complex between contactin-1 and the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPRZ controls the development of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17498–17503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108774108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harroch S., Palmeri M., Rosenbluth J., Custer A., Okigaki M., Shrager P., Blum M., Buxbaum J.D., Schlessinger J. No obvious abnormality in mice deficient in receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase beta. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7706–7715. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7706-7715.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harroch S., Furtado G.C., Brueck W., Rosenbluth J., Lafaille J., Chao M., Buxbaum J.D., Schlessinger J. A critical role for the protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type Z in functional recovery from demyelinating lesions. Nat Genet. 2002;32:411–414. doi: 10.1038/ng1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blakemore W.F., Franklin R.J.M. Remyelination in experimental models of toxin-induced demyelination. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;318:193–212. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73677-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lafont D., Adage T., Gréco B., Zaratin P. A novel role for receptor like protein tyrosine phosphatase zeta in modulation of sensorimotor responses to noxious stimuli: evidences from knockout mice studies. Behav Brain Res. 2009;201:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patrignani C., Lafont D.T., Muzio V., Gréco B., Hooft van Huijsduijnen R., Zaratin P.F. Characterization of protein tyrosine phosphatase H1 knockout mice in animal models of local and systemic inflammation. J Inflamm (Lond) 2010;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J.K., Jarjour A.A., Nait Oumesmar B., Kerninon C., Williams A., Krezel W., Kagechika H., Bauer J., Zhao C., Evercooren A.B.-V., Chambon P., French-Constant C., Franklin R.J.M. Retinoid X receptor gamma signaling accelerates CNS remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:45–53. doi: 10.1038/nn.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satpute-Krishnan P., DeGiorgis J.A., Conley M.P., Jang M., Bearer E.L. A peptide zipcode sufficient for anterograde transport within amyloid precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16532–16537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607527103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chidlow G., Ebneter A., Wood J.P.M., Casson R.J. The optic nerve head is the site of axonal transport disruption, axonal cytoskeleton damage and putative axonal regeneration failure in a rat model of glaucoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:737–751. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0807-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabriel A.F., Marcus M.A.E., Honig W.M.M., Walenkamp G.H.I.M., Joosten E.A.J. The CatWalk method: a detailed analysis of behavioral changes after acute inflammatory pain in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;163:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snyder S.E., Li J., Schauwecker P.E., McNeill T.H., Salton S.R. Comparison of RPTP zeta/beta, phosphacan, and trkB mRNA expression in the developing and adult rat nervous system and induction of RPTP zeta/beta and phosphacan mRNA following brain injury. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;40:79–96. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(96)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobbertin A., Rhodes K.E., Garwood J., Properzi F., Heck N., Rogers J.H., Fawcett J.W., Faissner A. Regulation of RPTPbeta/phosphacan expression and glycosaminoglycan epitopes in injured brain and cytokine-treated glia. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:951–971. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abe Y., Yamamoto T., Sugiyama Y., Watanabe T., Saito N., Kayama H., Kumagai T. Apoptotic cells associated with Wallerian degeneration after experimental spinal cord injury: a possible mechanism of oligodendroglial death. J Neurotrauma. 1999;16:945–952. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun F., Lin C.-L.G., McTigue D., Shan X., Tovar C.A., Bresnahan J.C., Beattie M.S. Effects of axon degeneration on oligodendrocyte lineage cells: dorsal rhizotomy evokes a repair response while axon degeneration rostral to spinal contusion induces both repair and apoptosis. Glia. 2010;58:1304–1319. doi: 10.1002/glia.21009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]