Summary

Malonyl-CoA is the rate determining metabolite for long chain de novo fatty acid synthesis and allosterically inhibits the rate-setting step in long chain fatty acid β-oxidation. We have developed a cell-based genetically encoded biosensor based on the malonyl-CoA responsive Bacillus subtilis transcriptional repressor, FapR, for living mammalian cells. Here we show that fluctuations in malonyl-CoA, in mammalian cells, can regulate the transcription of a FapR-based malonyl-CoA biosensor. The biosensor reflects changes in malonyl-CoA flux regulated by malonyl-CoA decarboxylase and AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in a concentration-dependent manner. To gain further insight into the regulatory mechanisms that effect fatty acid metabolism, we utilized the malonyl-CoA sensor to screen and identify several novel kinases. LIMK1 was identified and its expression was shown to alter both fatty acid synthesis and oxidation rates. This simple genetically encoded biosensor can be used to study the metabolic properties of live mammalian cells and enable screens for novel metabolic regulators.

Introduction

Metabolite analysis has been largely confined to laborious measurements of whole tissues or populations of cells which gives an incomplete picture of a presumably intimate metabolic cross talk between cells. The elusive nature of cellular metabolites is due mainly to their relatively low abundance and short-lived nature. Furthermore, most intermediary metabolites have a simple structure that although functionally distinct, precludes the generation of specific antibodies or stains. A simple cell-based assay is needed to explore tissue metabolic heterogeneity and to perform high throughput screens to identify modifiers of important metabolic pathways.

One of the central metabolic pathways in biology is the synthesis of saturated long chain fatty acids. Fatty acids are used for membrane biosynthesis, the production of signaling lipids, post-translational modification (e.g. palmitoylation), energy storage and energy production. The rate of de novo fatty acid synthesis is largely controlled by the highly regulated Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC) which carboxylates cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA (Fig. 1A). Malonyl-CoA is then used as the chain elongating unit for the synthesis of long chain fatty acids. Cytoplasmic malonyl-CoA also regulates fatty acid oxidation by allosterically inhibiting Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-1, the rate determining step in mitochondrial long chain fatty acid beta-oxidation. Therefore, malonyl-CoA is the regulatory link between the synthesis and oxidation of long chain fatty acids. While others have adapted bacterial proteins to generate unique FRET sensors for glutamate (Okumoto, et al., 2005), various carbohydrates (Fehr, et al., 2002; Fehr, et al., 2004; Fehr, et al., 2003; Fehr, et al., 2005; Lager, et al., 2003; Lager, et al., 2006), citrate (Ewald, et al., 2011) and nucleotides (Berg, et al., 2009), there are a dearth of tools available to study fatty acid metabolism.

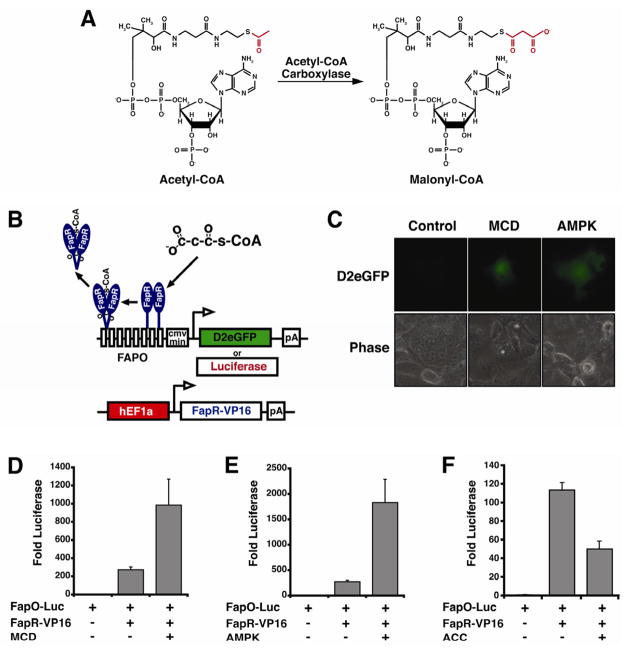

Figure 1. Development of a genetically encoded malonyl-CoA sensor.

(A) The structurally similar but functionally distinct acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA. (B) Schematic of the genetically-encoded sensor based on the Bacillus subtilis transcriptional regulator, FapR. (C) Depletion of malonyl-CoA by expression of a cytoplasmically targeted Malonyl-CoA Decarboxylase (MCD) or inhibiting the synthesis of malonyl-CoA by expression of a constitutively active AMPKgamma (R70Q) (AMPK) induces the expression of the destablized eGFP (D2eGFP) reporter or (D–E) luciferase reporter. (D–F) Y axis shows the fold increase of luciferase luminescence normalized to beta-galactosidase activity relative to FapO-Luc alone. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

In gram positive bacteria, the synthesis of saturated fatty acids is transcriptionally regulated by the Fatty acid and phospholipid Regulator (FapR) (Schujman, et al., 2003). FapR is a transcriptional repressor that inhibits transcription of most genes involved in the fatty acid biosynthetic pathway. FapR undergoes a conformational shift when bound by malonyl-CoA that releases it from its operator (Kd=2.4μM), thereby allowing transcription of fatty acid biosynthetic genes (Schujman, et al., 2006). Therefore, these bacteria utilize malonyl-CoA as a concentration dependent DNA binding inhibitor. The specificity of this interaction has been further validated by the crystallization of FapR bound to malonyl-CoA (Schujman, et al., 2006).

Here we have produced a simple genetically encoded biosensor for mammalian cells that takes advantage of the malonyl-CoA dependent DNA binding properties of FapR. The biosensor is transcriptionally regulated by malonyl-CoA, thus reporter gene activity is correlated with the concentration of malonyl-CoA. We used the malonyl-CoA biosensor for a small scale expression screen to discover and validate novel kinases that regulate fatty acid metabolism. This simple malonyl-CoA biosensor design can be used to study the metabolic properties of live mammalian cells and enable screens to discover unknown metabolic regulators.

Results and Discussion

Generation of a mammalian Malonyl-CoA sensor

We have adapted the bacterial FapR transcriptional regulatory system to generate a cell-based biosensor that can be used to detect changes in malonyl-CoA in mammalian cells. FapR, from Bacillus subtilis was codon optimized and synthesized for mammalian expression. FapR was then cloned into a mammalian expression vector and fused in-frame with the herpes simplex virus transcriptional activator, VP16. The VP16 fusion converts FapR from a bacterial transcriptional repressor into a transcriptional activator in the absence of malonyl-CoA. The 34 base pair fragment from the FapR operon (FapO) that is protected from DNase digestion by FapR binding was multerimized with a short linker and cloned upstream of a CMV minimal promoter driving either luciferase or a destabilized short half-life (~2hr) green fluorescent protein (D2eGFP) (Fig. 1B). The CMV minimal promoter provides the basic promoter elements including the TATA box and transcription initiation, but is relatively inert in the absence of an enhancer (Fig. 1D–F).

Next we wanted to validate that the malonyl-CoA biosensor was transcriptionally responsive to malonyl-CoA in mammalian cells. We were able to successfully co-express FapR-VP16 and the FapO-D2eGFP or FapO-Luciferase reporter in COS-1 cells (Fig. 1C–F). To validate the sensor, the concentration of cellular malonyl-CoA was altered in cells expressing the reporter plasmids by co-expressing enzymes that affect the concentration of malonyl-CoA. Co-expression of a cytoplasmically targeted Malonyl-CoA Decarboxylase (MCD) to catabolize malonyl-CoA to acetyl-CoA and CO2 and lower cellular malonyl-CoA content (An, et al., 2004; Hu, et al., 2005; Rodriguez and Wolfgang, 2012) resulted in increased reporter fluorescence (Fig. 1C) or luminescence (Fig. 1D). Additionally, we co-expressed a constitutively active 5′-AMP Activated Protein Kinase-γ1 (R70Q) subunit (AMPK) (Hamilton, et al., 2001), to inhibit ACC and therefore malonyl-CoA synthesis, which resulted in increased reporter fluorescence (Fig. 1C) or luminescence (Fig. 1E). Alternatively, the co-transfection of ACC1, to increase cellular malonyl-CoA, suppressed luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 1F).

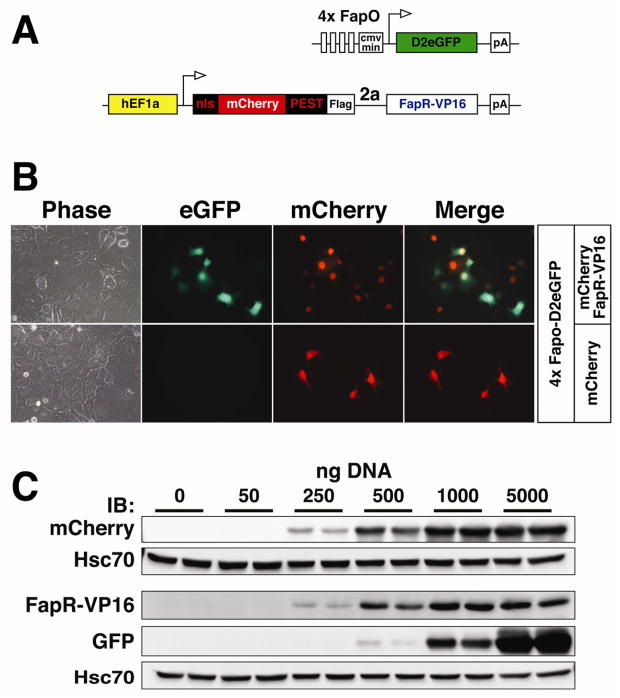

The malonyl-CoA sensor signal depends on both transfection efficiency and transcriptional activity of the cells; therefore, we modified the FapR-VP16 construct to include a destabilized mCherry fluorescent protein to control for both transfection and stability (Fig. 2A). A picornavirus PTV1-2A peptide-linked destabilized mCherry was fused in-frame before FapR-VP16. The 2A peptide allows two proteins to be produced from a single mRNA at a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio, enabling a ratiometric, autonomous measurement of transfection within cells (Rodriguez and Wolfgang, 2012; Szymczak, et al., 2004). To enable a comparison between mCherry and destabilized eGFP, the PEST sequence from ornithine decarboxylase (also used in D2eGFP) was fused to mCherry along with a nuclear localization sequence (nls) to better visualize the transgene (Fig. 2A). Images of the nuclear localized-fluorophore labeled FapR construct are shown in transfected COS-1 cells (Fig. 2B). As in Fig. 1D–F, in the absence of FapR-VP16 there is minimal expression of the reporter, but the addition of FapR-VP16, as visualized by mCherry expression, greatly enhances eGFP expression (Fig. 2B). Increasing transfection of each plasmid in to COS-1 cells demonstrated an increase in both the GFP and mCherry fluorescent signal as expected (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Fluorescent Malony-CoA biosensor.

(A) Schematic representation of the FapO-d2eGFP and nls-mCherry-PEST-Flag-2a-FapR-VP16 reporters. (B) Phase contrast bright field, or epifluorescent eGFP, mCherry, and merge overlay images (40X magnification) of COS-1 cells transfected with the FapO-eGFP and mCherry-FapR-VP16 (top panel) or FapO-eGFP and mCherry reporter constructs. (C) Western blot images of COS-1 cells co-transfected with increasing equimolar amounts of the FapO-eGFP reporter plasmid and nls-mCherry-PEST-Flag-2a-FapR-VP16 from 0ng to 5000ng DNA of each, and probed for anti-FLAG (representing the NLS-mCherry-PEST-FLAG), anti-VP16 (representing FapR-VP16), GFP, and the housekeeping protein HSC70.

Dynamics of the Malonyl-CoA biosensor

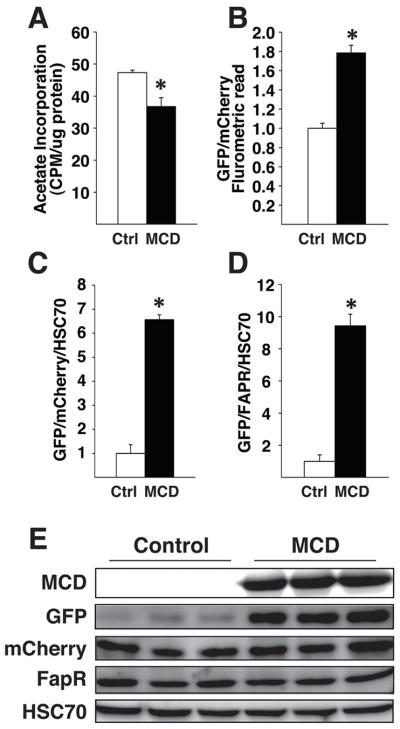

To verify that the malonyl-CoA biosensor can determine relative qualitative differences in malonyl-CoA in living mammalian cells, we expressed MCD in COS-1 cells and measured [3H]-acetate incorporation into lipids while simultaneously measuring reporter activity. The expression of MCD in COS-1 cells resulted in decreased [3H]-acetate incorporation into lipids as expected (Fig. 3A). The malonyl-CoA reporter showed an increase in the GFP/mCherry ratio as measured by direct cellular fluorescence by a fluorometric platereader (Fig. 3B). Subsequently, cell lysate was subjected to Western blot analysis for detection of all transfected components (Fig. 3E). Western blot densitometry showed a large increase in the ratio of GFP/mCherry (Fig. 3C) and an even larger increase in the ratio of GFP/FapR (Fig. 3D). While both fluorescent reading and western blot analysis similarly reflect biosensor activity, in our hands Western blot analysis is a more sensitive measure than direct fluorescence reading. Given the laborious nature of Western blot analysis, the convenience of direct fluorescence measurement makes fluorescence reading more desirable for initial screening and subsequent applications. The GFP/mCherry ratio is modest in comparison to the GFP/FapR ratio, accurately reflecting the short-lived nature of the destabilized mCherry and long-lived nature of the FapR-VP16.

Figure 3. Malonyl-CoA biosensor altered by depleting cellular malonyl-CoA.

(A) [3H]-acetate incorporation into lipids, (B) fluorometric reading of GFP relative to mCherry. (C) GFP protein abundance relative to mCherry or (D) FapR-VP16 protein abundance normalized to HSC70 housekeeping protein that was quantified from Western Blot images in (E). Western blot was probed with antibodies directed against V5 (MCD), GFP, FLAG (mCherry), VP16 (FapR-VP16), or HSC70 from COS-1 cells plated in 60mm dishes and co-transfected with 50ng of FapO-eGFP, 50 ng of mCherry-FapR-VP16, and 500 ng of either control (ctrl) or malonyl-CoA decarboxylase (MCD) expressing plasmid DNA. * p < 0.05, by Student’s T-test. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Western blots were developed using fluorescent secondary antibodies and quantified via AlphaInnotech MultiImage III.

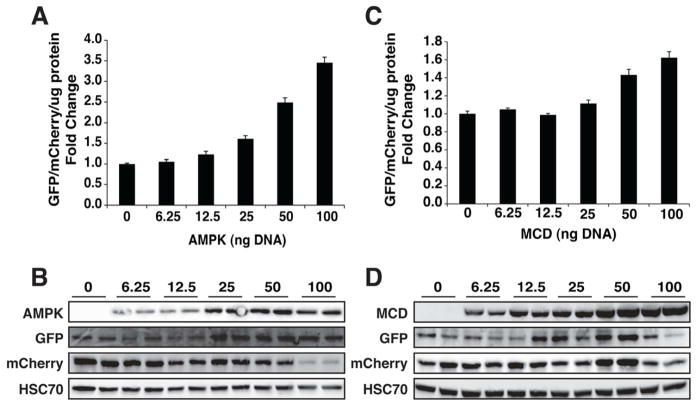

Next, we expressed increasing concentrations of AMPK or MCD in COS-1 cells. AMPK phosphorylates and deactivates ACC thereby reducing malonyl-CoA flux through de novo fatty acid synthesis, and correspondingly we show that increasing the expression of exogenous AMPK increased the reporter fluorescence reading and protein abundance in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 4A, B). Likewise, increasing the expression of MCD, an enzyme that converts malonyl-CoA to acetyl-CoA, thereby depleting cellular malonyl-CoA, showed a dose-dependent increase in reporter fluorescence reading and protein abundance (Fig. 4C, D). AMPK, while a robust inhibitor of ACC, also inhibits protein synthesis and augments autophagy (Kahn, et al., 2005) and thus effects the protein abundance of FapR-VP16 and mCherry but retains the expected GFP/mCherry ratio. These data show that modulating malonyl-CoA metabolizing enzymes induced the predicted changes in reporter activity of this genetically encoded malonyl-CoA biosensor.

Figure 4. Malonyl-CoA biosensor titration.

GFP fluorescent quantification relative to mCherry fluorescence read in a fluorescent plate reader, normalized to protein, in COS-1 cells plated in 24-well plates and co-transfected with 5ng FapO-eGFP reporter DNA, 50ng nls-mCherry-PEST-Flag-2a-FapR-VP16, and increasing levels of constitutively active AMPK gamma (R70Q) DNA (A) or MCD DNA (C). Western blot images and quantification of COS-1 cells described above and probed against GFP, FLAG (mCherry), HSC70, and HA (AMPK) (B) or V5 (cMCD) (D).

Identifying novel mechanisms to affect malonyl-CoA concentration

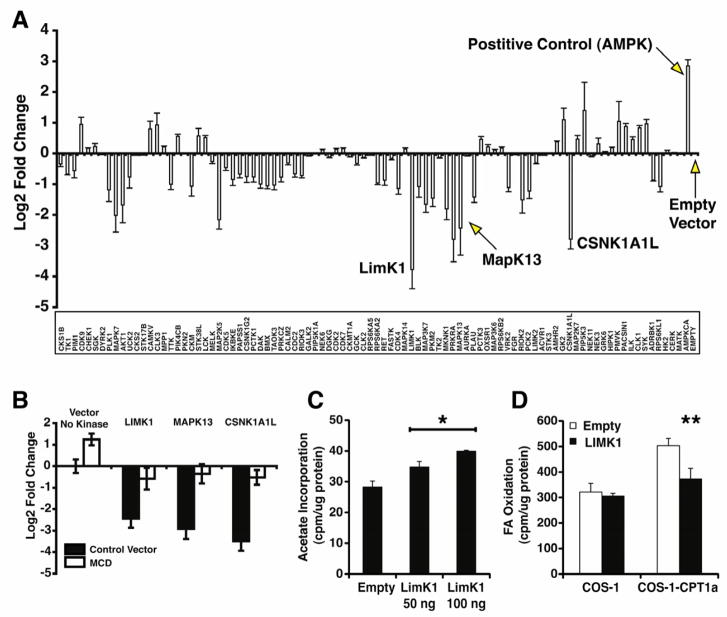

The enzymatic regulation of fatty acid synthetic and degradative pathways has been thoroughly examined (Wakil and Abu-Elheiga, 2009). However, the signaling mechanisms that translate extracellular cues into alterations in mammalian cellular metabolism are less clear. To gain mechanistic insight into how diverse signaling cascades regulate malonyl-CoA concentration, we used the reporter activity of the malonyl-CoA biosensor to screen a myristoylated human kinase expression library (Boehm, et al., 2007) in COS-1 cells (Fig. 5A). AMPK was used as a positive control and the empty vector was used as a negative control. Several novel kinases were found that decreased reporter activity and thus increase malonyl-CoA concentration. We preformed a secondary counter screen with or without MCD co-expression on a subset of seven kinases that changed reporter signal greater than 2-fold (Mapk7, Akt1, Map2K5, Prkra, LIMK1, MAPK13, and CSNK1A1L) and we found that the LIMK1, MAPK13, and CSNK1A1L kinases did appear to increase malonyl-CoA content because reporter activity was reversed with the expression of MCD (Fig. 5B). Here we have shown the FapR-based malonyl-CoA biosensor can be used to identify possible mediators of fatty acid metabolism.

Figure 5. Identification of novel signaling regulators of fatty acid synthesis via expression screening.

(A) COS-1 cells were co-transfected with the malonyl-CoA biosensor and 100ng DNA of myristoylated kinase plasmids in quadruplicate. A constitutively active AMPK gamma (R70Q) was used as the positive control and an empty vector was used as the negative control. (B) A subset of kinases that were identified in the screen were subjected to a secondary screen with or without MCD. (C) COS-1 cells co-transfected with 100ng LIMK1 DNA and sensor expression plasmids have increased de novo lipid synthesis assayed by the incorporation of 3H-acetate into lipids. (D) COS-1 cells with or without stable expression of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1a (COS-1-CPT1a) (Reamy and Wolfgang, 2011) were co-transfected with a 100ng LIMK1 and sensor expression plasmids. LIMK1 suppressed CPT1a mediated oxidation of [9,10 3H] palmitic acid. * p < 0.05, **p < 0.005 by Student’s T-test. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Next, we chose to further validate the regulation of fatty acid metabolism by LIMK1. Decreased signal from the malonyl-CoA reporter induced by co-transfection with LIMK1 suggests an increase in metabolic flux through lipid synthesis and a simultaneous suppression of fatty acid beta-oxidation. To confirm that the sensor activity reflects changes in the flux of fatty acid biosynthesis we performed the standard biochemical assay for de novo fatty acid synthesis, [3H]-acetate incorporation into lipids, on cells transfected with LIMK1. As expected, increasing concentrations of LIMK1 DNA increased the rate of de novo fatty acid synthesis (Fig 5C). This suggests that LIMK1 alters fatty acid metabolism consistent with the malonyl-CoA biosensor activity. The LIMK1-induced reduction in the malonyl-CoA sensor reflected an increase in the rate of cellular fatty acid synthesis. To further validate the malonyl-CoA sensor, we performed long chain fatty acid oxidation assays (by collecting 3H2O derived from the full oxidation of [9,10 3H] palmitate) on COS-1 cells expressing Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-1a (CPT1a), the rate setting enzyme in fatty acid oxidation that is potently inhibited by cytoplasmic malonyl-CoA. As predicted, the rates of fatty acid oxidation were significantly decreased in the LIMK1 expressing COS-1-Cpt1a cells (Fig. 5D), suggesting that LIMK1 increases malonyl-CoA thereby inhibiting CPT1a activity. LIMK1 has been shown to be critical for neurite outgrowth in vitro (Endo, et al., 2007). LIMK1 is linked to the regulation neurite extension through its regulation of cofilin, a regulator of actin cytoskeletal dynamics (Takemura, et al., 2009). Here, we show that LIMK1 increases the rate of de novo fatty acid synthesis when expressed in COS-1 cells. While neurite extension most certainly requires cytoskeletal rearrangement, outgrowth may also require the formation of new fatty acids for the synthesis of phospholipids used for membrane extension. Our malonyl-CoA sensor kinase screen has revealed a novel role for LIMK1 in altering cellular fatty acid metabolic rates.

SIGNIFICANCE

Here we have developed a novel genetically encoded biosensor for an important but elusive metabolite, malonyl-CoA. This simple methodology can be used to dissect cell specific metabolic properties in complex tissues or can be used to perform screens to identify new modes of metabolic regulation. A limitation of our sensor is that the reporter signal relies upon the transcriptional and translational activity of the host cell and can only respond to nucleocytoplasmic metabolites. This is why counter screening, metabolite flux analysis using labeled substrates, or direct measurements of the metabolite are required as orthogonal measures to confirm that the effect is specific for a change in metabolite flux. Additionally, in order to obtain reliable reporter activity, both the reporter and activator need to be controlled for as we have shown.

FRET-based sensors have been very useful for determining the temporal and subcellular resolution of small molecules, but have been limited in their utility for large scale screening or in vivo use. The metabolite sensitive transcriptional reporters described here are analogous to the widely used tetracycline regulated transcriptional control that has been used extensively in vitro and in vivo (Lee, et al., 1998; Li, et al., 2005; Mayford, et al., 1996; Nguyen, et al., 2006). The use of bacterial-derived metabolite sensitive transcriptional reporters eliminates the requirement to overexpress endogenous enzymes or transcription factors, the requirement to modify the metabolite directly, and the requirement to modify endogenous metabolite generating or degrading enzymes. More broadly, bacteria encode a wealth of small molecule regulated transcription factors that could be similarly modified to understand equally onerous-to-study molecules.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Constructs

A mammalian codon optimized FapR cDNA was synthesized and cloned as an N-terminal fusion protein to VP16 in a mammalian expression vector, pEF6 (Life Technologies). Additionally, DNA encoding a nuclear localization sequence, a PEST sequence, mCherry, FLAG, and the self-cleaving 2A peptide sequence were synthesized (Life Technologies) and inserted into the FapR-VP16 plasmid by In-fusion (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). A 34 base pair fragment of the FapR operon was PCR amplified and multimerized then cloned upstream to a CMV minimal promoter and firefly luciferase cDNA or a destabilized eGFP. Transfections were performed with Fugene HD at a microgram DNA to microliter Fugene ratio of 1:3 (Promega). For all transfections 50ng each of FapR-VP16, FapO-GFP, and FapO-Luc expression plasmids were transfected, unless otherwise specified. Luciferase assays were normalized by co-transfection with CMV-βgal. Luciferase assays (Promega) were done in quadruplicate and normalized to beta galactosidase activity (Pierce) per manufacturer’s instructions. The myristoylated human kinase library was obtained from Addgene (#1000000012). Constructs for MCD were generated by PCR amplification of mouse skeletal muscle cDNA as previously published (An, et al., 2004). HA-tagged AMPKgamma (R70Q) plasmids (Hamilton, et al., 2001) have been previously described. A mammalian expression vector for ACC1 was purchased from Life Technologies.

De novo fatty acid synthesis

COS-1 cells transfected with a kinase expression plasmid were labeled with trace levels (1.0 μCi) of [3H] acetic acid acetate (Perkin Elmer) for 1 hr. Total lipids were extracted with chloroform/methanol via Folch method (Folch, et al., 1957) and radioactivity was counted via liquid scintillation.

Fatty acid oxidation

COS-1 cells or COS-1 cells expressing Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1a (CPT1a) (Reamy and Wolfgang, 2011) transfected with a kinase expression plasmid were incubated with BSA-conjugated [9,10 3H] palmitate (Perkin Elmer) for 2 hrs. The media was acidified, precipitated, then neutralized and 3H2O was isolated through ion exchange chromatography as previously reported and radioactivity was counted via liquid scintillation (Buzzai, et al., 2005).

Reporter quantification

Fluorescent signal was measured by plate reader at 485nm excitation and 528nm emission for green fluorescence protein and 550nm excitation and 610nm emission for mCherry on a BioTek SynergyMx plate reader (Winooski, VT). The GFP signal was normalized to mCherry signal and values were normalized to the control treated cells. Western blots were quantified using Alpha Innotech FluorChem Q Software (Santa Clara, CA) in which 20ug protein were loaded onto 8% SDS/polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 5% Non-fat dry milk in TBS-1% Tween-20. Primary antibodies were GFP (Santa Cruz sc-9996), FLAG (Agilent cat#200470-21), VP16 (Santa Cruz, sc-7545), V5 (Invitrogen P/N46-0705 Santa Cruz), HA (Roche cat#11867423001), and HSC70 (Santa Cruz, sc-7298).

HIGHLIGHTS.

Genetically-encoded sensor for malonyl-CoA, a central node in fatty acid biochemistry.

Simple method to measure metabolites for live cell imaging or high throughput screening.

Changes in the metabolite are correlated with reporter gene activity.

Broadly applicable platform for metabolite analysis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Violeta Capric (Wagner College) for technical assistance. J.M.E was supported by an interdepartmental training program in cellular and molecular endocrinology (T32DK007751). This work was supported in part by the American Heart Association (SDG2310008 to M.J.W.) and NIH NINDS (NS072241 to M.J.W.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- An J, Muoio DM, Shiota M, Fujimoto Y, Cline GW, Shulman GI, Koves TR, Stevens R, Millington D, Newgard CB. Hepatic expression of malonyl-CoA decarboxylase reverses muscle, liver and whole-animal insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2004;10:268–274. doi: 10.1038/nm995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J, Hung YP, Yellen G. A genetically encoded fluorescent reporter of ATP:ADP ratio. Nature methods. 2009;6:161–166. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm JS, Zhao JJ, Yao J, Kim SY, Firestein R, Dunn IF, Sjostrom SK, Garraway LA, Weremowicz S, Richardson AL, et al. Integrative genomic approaches identify IKBKE as a breast cancer oncogene. Cell. 2007;129:1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzai M, Bauer DE, Jones RG, Deberardinis RJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Elstrom RL, Thompson CB. The glucose dependence of Akt-transformed cells can be reversed by pharmacologic activation of fatty acid beta-oxidation. Oncogene. 2005;24:4165–4173. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M, Ohashi K, Mizuno K. LIM kinase and slingshot are critical for neurite extension. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:13692–13702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald JC, Reich S, Baumann S, Frommer WB, Zamboni N. Engineering genetically encoded nanosensors for real-time in vivo measurements of citrate concentrations. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr M, Frommer WB, Lalonde S. Visualization of maltose uptake in living yeast cells by fluorescent nanosensors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:9846–9851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142089199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr M, Lalonde S, Ehrhardt DW, Frommer WB. Live imaging of glucose homeostasis in nuclei of COS-7 cells. Journal of fluorescence. 2004;14:603–609. doi: 10.1023/b:jofl.0000039347.94943.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr M, Lalonde S, Lager I, Wolff MW, Frommer WB. In vivo imaging of the dynamics of glucose uptake in the cytosol of COS-7 cells by fluorescent nanosensors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:19127–19133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr M, Takanaga H, Ehrhardt DW, Frommer WB. Evidence for high-capacity bidirectional glucose transport across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane by genetically encoded fluorescence resonance energy transfer nanosensors. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:11102–11112. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.11102-11112.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SR, Stapleton D, O’Donnell JB, Jr, Kung JT, Dalal SR, Kemp BE, Witters LA. An activating mutation in the gamma1 subunit of the AMP-activated protein kinase. FEBS letters. 2001;500:163–168. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SR, Stapleton D, O’Donnell JB, Jr, Kung JT, Dalal SR, Kemp BE, Witters LA. An activating mutation in the γ1 subunit of the AMP-activated protein kinase. FEBS Letters. 2001;500:163–168. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Dai Y, Prentki M, Chohnan S, Lane MD. A Role for Hypothalamic Malonyl-CoA in the Control of Food Intake. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:39681–39683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005;1:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lager I, Fehr M, Frommer WB, Lalonde S. Development of a fluorescent nanosensor for ribose. FEBS letters. 2003;553:85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00976-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lager I, Looger LL, Hilpert M, Lalonde S, Frommer WB. Conversion of a putative Agrobacterium sugar-binding protein into a FRET sensor with high selectivity for sucrose. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:30875–30883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Morley G, Huang Q, Fischer A, Seiler S, Horner JW, Factor S, Vaidya D, Jalife J, Fishman GI. Conditional lineage ablation to model human diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:11371–11376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XD, Sun L, Seth RB, Pineda G, Chen ZJ. Hepatitis C virus protease NS3/4A cleaves mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein off the mitochondria to evade innate immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:17717–17722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508531102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayford M, Bach ME, Huang YY, Wang L, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER. Control of memory formation through regulated expression of a CaMKII transgene. Science. 1996;274:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H, Rendl M, Fuchs E. Tcf3 governs stem cell features and represses cell fate determination in skin. Cell. 2006;127:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumoto S, Looger LL, Micheva KD, Reimer RJ, Smith SJ, Frommer WB. Detection of glutamate release from neurons by genetically encoded surface-displayed FRET nanosensors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:8740–8745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503274102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reamy AA, Wolfgang MJ. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1c gain-of-function in the brain results in postnatal microencephaly. Journal of neurochemistry. 2011;118:388–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez S, Wolfgang MJ. Targeted chemical-genetic regulation of protein stability in vivo. Chemistry & biology. 2012;19:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schujman GE, Guerin M, Buschiazzo A, Schaeffer F, Llarrull LI, Reh G, Vila AJ, Alzari PM, de Mendoza D. Structural basis of lipid biosynthesis regulation in Gram-positive bacteria. The EMBO journal. 2006;25:4074–4083. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schujman GE, Paoletti L, Grossman AD, de Mendoza D. FapR, a bacterial transcription factor involved in global regulation of membrane lipid biosynthesis. Developmental cell. 2003;4:663–672. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Dilioglou S, Vanin EF, Vignali DA. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemura M, Mishima T, Wang Y, Kasahara J, Fukunaga K, Ohashi K, Mizuno K. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV-mediated LIM kinase activation is critical for calcium signal-induced neurite outgrowth. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:28554–28562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakil SJ, Abu-Elheiga LA. Fatty acid metabolism: target for metabolic syndrome. Journal of lipid research. 2009;50(Suppl):S138–143. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800079-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]