Abstract

The present study describes the development and initial validation of a new obesity-specific, self-report measure of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) for children aged 5–13 years. Participants included 141 obese children (mean age = 9.2 years, 67% female, 55% black, mean zBMI = 2.52) and their primary caregivers. Children completed Sizing Me Up (obesity-specific HRQOL) and the PedsQL (generic HRQOL). Item content for Sizing Me Up was based on the published child obesity and HRQOL literatures and expert opinion. Items use phrasing to orient children to respond to questions in context of his/her size (e.g., “were teased by other kids because of your size”). Caregivers completed Sizing Them Up, a parallel parent-proxy, obesity-specific HRQOL measure. Initial psychometric evaluation of Sizing Me Up was completed by conducting a factor analysis and determining internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent and construct validity. Sizing Me Up is a 22-item measure with five scales (i.e., Emotional Functioning, Physical Functioning, Social Avoidance, Positive Social Attributes, and Teasing/Marginalization) that account for 57% of the variance and a total HRQOL score. Internal consistency coefficients range from 0.68 to 0.85. Test–retest reliabilities range from 0.53 to 0.78. Good convergent validity was demonstrated with the PedsQL (rs = 0.35–0.65) and the parent-proxy Sizing Them Up (rs = 0.22–0.44). Sizing Me Up represents the first obesity-specific HRQOL measure developed specifically for younger school-aged children (aged 5–13 years) with preliminary evidence of strong psychometric properties that likely has both clinical and research utility in a variety of settings.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 24% of young children (aged 2–5 years) and 34% of elementary school-age children and adolescents are either overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 85th percentile) in the United States (1). Consequently, a notable percentage of today’s youth face management of obesity-related health (2) and psychosocial (3) risks and consequences without successful intervention. Accordingly, the past decade has shown a growing interest in characterizing the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of obese youth in an effort to fully document the impact of this public health crisis.

To date, 17 published studies have described the HRQOL of obese youth and documented significant impairments in physical, emotional, and social well-being (4–19).Until recently, pediatric researchers have been limited to use of generic self-report and/or parent-proxy measures (20–22) when characterizing HRQOL in obese youth. Whereas these generic measures have utility and allow for cross-disease comparisons (10), generic measures do not assess aspects of child daily functioning that are specific to being obese and likely lack the specificity and sensitivity of condition-specific instruments (23).

Currently, two measures are available to pediatric researchers to characterize the impact of weight or obesity on youth daily functioning. The Impact of Weight on Quality of Life–Kids (18) was specifically designed to assess key domains of weight-related HRQOL for older school-aged children and adolescents aged 11–18 years (i.e., physical comfort, body esteem, social life, and family relations) and has strong psychometric properties. However, no disease-specific measures existed that captured the HRQOL of younger obese children. In response, we recently presented a psychometrically strong, parent-proxy, obesity-specific HRQOL measure for youth aged 5–18 years, Sizing Them Up (24). Given the compelling evidence in the broader HRQOL literature supporting the use of pediatric patient self-report (vs. parent-proxy) as the “standard” source when characterizing patient status or treatment outcomes (25), the critical need for a parallel self-report, obesity-specific measure for children was clear.

The aims of the present study were to describe the development and initial validation (e.g., reliability and validity) of a self-report, obesity-specific measure of HRQOL for children aged 5–13 years called Sizing Me Up. It was expected that Sizing Me Up would have internally consistent factors (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70), good test–retest reliability, and moderate agreement with similar scales on a generic self-report HRQOL measure (PedsQL); the parent-proxy, obesity-specific measure (Sizing Them Up); and zBMI. Secondary study aims included examination of gender and race differences on Sizing Me Up.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Participants and procedures

Study participants included 141 obese children aged 5–13 years and caregivers seeking treatment through a hospital-based pediatric weight management program. The program requires a physician referral and a BMI ≥95th percentile. Participants included in the current analyses represent a subset of younger children from a pooled sample of two larger consecutive studies examining the HRQOL of obese youth. Procedures were consistent across both studies, although the second study had two phases as described below. Larger eligibility criteria included (i) children being 5–18 years of age, (ii) willingness to comply with study procedures, (iii) provision of written informed consent/assent, and (iv) exclusion of youth with developmental disabilities or significant reading difficulties. Study protocols were approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Phase 1

Between August 2004 and January 2007, all patients who had scheduled a first appointment with the pediatric weight management program were mailed brochures describing a study about HRQOL in obese youth. Potential participants were subsequently approached for recruitment and participation during their first appointment, either a medical screening visit at the General Clinical Research Center or an intake evaluation with the treatment team. One hundred fifty-one of 159 (95%) agreed to study participation. The final sample (n = 141) reflects the exclusion of several participants: (i) five participants were one of two siblings and (ii) five participants had difficulty understanding the questionnaires due to reading difficulties and/or English being a second language. Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and anthropometrics

| N | Mean (s.d.) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 9.2 (2.2) | ||

| 5–7 | 46 | 33 | |

| 8–10 | 57 | 40 | |

| 11–13 | 38 | 27 | |

| Sex | |||

| Girls | 95 | 67 | |

| Boys | 46 | 33 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 55 | 39 | |

| Black | 78 | 55 | |

| Biracial/other | 8 | 6 | |

| Participating caregiver | |||

| Mother | 124 | 88 | |

| Father | 4 | 3 | |

| Grandmother | 9 | 6 | |

| Other | 4 | 3 | |

| Socioeconomic statusa | 36.7 (20.4) | ||

| Child anthropometric data | |||

| BMI | 31.8 (6.2) | ||

| Standardized BMI (zBMI) | 2.5 (0.35) |

Based upon Duncan TSEI2 for head of household, a measure of occupational attainment. The mean TSEI2 score reflects occupations such as clerks, typists, and machine operators.

All personnel were trained to recruit and screen participants, obtain consent/assent, and administer questionnaires. For the current study, children completed the self-report PedsQL and the newly developed Sizing Me Up. Caregivers completed a demographic form and the parent-proxy Sizing Them Up. Participants were compensated with a $10 gift card to local stores for their time.

Phase 2: Test–retest reliability

Those participants recruited between August 2005 and January 2007 were approached for a second study phase designed to assess test–retest reliability of Sizing Me Up. Approximately 2–4 weeks after completion of phase 1, research assistants administered a second set of questionnaires at the family’s home or a mutually agreed upon location. Height and weight measurements were taken to ensure no significant changes occurred in zBMI from phase 1, which would compromise stability over time. Of the potential 103 participants between 5 and 13 years of age who agreed to phase 1 and were approached for phase 2, 97 agreed to participate (94%). Eleven participants consented but had difficulties scheduling the phase 2 visit, three participants were one of two siblings, two participants had difficulty understanding the questionnaires due to reading difficulties or English being a second language, and one had an invalid phase 2 weight measurement, resulting in a final test–retest reliability sample of 80 participants.

Measures

Sizing Me Up

This instrument was developed by the current investigators to assess child self-report of obesity-specific HRQOL and targets youth aged 5–13 years. Item content was based on the published pediatric obesity and HRQOL literature, as well as expert advice from three independent pediatric obesity clinicians and researchers. The original core set of 30 items assessed physical functioning and discomfort, school functioning, emotional functioning, peer relations and victimization, and social withdrawal. All items use phrasing to orient children to respond to questions in context of their size (e.g., “…because of my size”). Language is developmentally appropriate and in first person tense. The directions and practice items are read aloud to all participants. For children 10 years of age and younger, items are then administered in an individual-interview format, with older children completing the measure independently. Participants are oriented to the four response choices (i.e., none to all of the time) both verbally and visually (see Supplementary Data online).

Sizing Them Up

Sizing Them Up (24) is a 22-item parent-proxy measure of obesity-specific HRQOL designed in parallel with Sizing Me Up. All items use phrasing to orient parents to respond to questions in context of the child’s weight/shape/size (e.g., “…because of their weight/shape/size”). The four response choices range from “never” to “always.” Sizing Them Up is composed of six scales (i.e., Emotional Functioning, Physical Functioning, Teasing/Marginalization, Positive Social Attributes, Mealtime Challenges, and School Functioning) and a total score. Scales are standardized and scores range from 0–100, with higher scores representing better quality of life. Sizing Them Up had internal consistency coefficients ranging from 0.59 to 0.91 and test–retest reliabilities ranging from 0.57 to 0.80. Sizing Them Up also demonstrated good convergent validity with other HRQOL measures and responsiveness to change related to weight loss.

PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales

The PedsQL (20), a self-report measure of generic HRQOL with parallel versions for children 5–7 years and 8–12 years, was utilized. The PedsQL consists of four core scales, including physical, emotional, social, and school functioning; a broad summary score (psychosocial functioning); and a total score. The PedsQL has been shown to be both reliable and valid for use with children as young as age 5, with internal consistency reliability coefficients approaching or exceeding 0.70 (20,25).

Weight and height

Child height and weight were measured by General Clinical Research Center or clinic nurses in phase 1 and abstracted from the medical record. For phase 2, trained research assistants measured weight (0.1 kg) on a portable SECA digital scale (SECA, Hamburg, Germany) and standing height with a calibrated custom portable stadiometer (Creative Health Products, Plymouth, MI). Weight and height measurements were taken in triplicate and the mean was used in analyses. Height and weight data were used to calculate BMI (kg/m2) and the standardized zBMI using the LMS method (26) based on the CDC 2000 growth curves (27).

Demographic questionnaire

Caregivers completed a brief family demographic questionnaire. Occupational data were used to calculate the Revised Duncan (TSEI2) (28) for each family, an occupation-based measure of socioeconomic status (29,30). TSEI2 scores range from 15 to 97, with higher scores representing greater occupational attainment. For two-caregiver households, the higher TSEI2 score was used in analyses.

Statistical and data analyses

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were used to characterize demographic and anthropometric variables. Exploratory factor analyses using principal axis factoring with promax rotation were performed on the Sizing Me Up 30-item pool. Items were deleted for several reasons, including high cross-loadings (i.e., loadings of >0.35 on three or more scales when the original loading was below 0.60) or low factor loadings (<0.40 (ref. 31)). After determination of a meaningful factor structure, internal consistency coefficients using Cronbach’s alpha were calculated for each scale. Test–retest reliability was determined using intraclass correlation coefficients. An intraclass correlation coefficient of ≥0.80 suggests excellent agreement; between 0.61 and 0.79, moderate agreement; and between 0.41 and 0.60, fair agreement (32).

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between similar scales on Sizing Me Up and scales on the (i) PedsQL child self-report and (ii) the parent-proxy Sizing Them Me Up. Pearson correlations were also calculated between zBMI and Sizing Me Up subscales. Finally, multivariate analyses of variance were conducted to examine race and gender differences on Sizing Me Up scales, after controlling for zBMI. Analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (version 14.0, 2006; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Factor analysis

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to examine 30 items on the Sizing Me Up measure. Eigenvalues and scree plot data supported the use of a three- to six-factor solution. Each of these solutions was examined with respect to the pattern of item loadings, cross-loadings, and conceptual meaning. A five-factor solution was chosen because it separated a moderate number of items into factors that were statistically distinct and interpretable. This resulted in a final instrument with 22 items.

Sizing Me Up scales and items

Sizing Me Up is a 22-item measure consisting of five scales: Emotional Functioning, Physical Functioning, Social Avoidance, Positive Social Attributes, and Teasing/Marginalization. The scales, corresponding items, and item loadings of the factor analysis are presented in Table 2. The percentage variance accounted for by the 22-item measure was 57%. Internal consistency coefficients for each scale are strong (Table 3), ranging from α = 0.68 for Positive Social Attributes scale and α = 0.85 for Emotional Functioning. Factor intercorrelations were positive and ranged from 0.01 to 0.58 (Table 4).

Table 2.

Exploratory factor loadings (n = 141)

| Item | Mean | s.d. | Emotion | Physical | Social Avoidance |

Positive Social Attributes |

Teasing/ Marginalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Felt worried | 2.25 | 1.15 | 0.80 | 0.34 | 0.32 | −0.04 | 0.38 |

| Felt mad | 2.17 | 1.15 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 0.48 | −0.06 | 0.46 |

| Felt sad | 2.23 | 1.05 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.33 | −0.20 | 0.30 |

| Felt frustrated | 2.22 | 1.15 | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.32 |

| Found it hard to keep up with other kids | 2.10 | 1.05 | 0.47 | 0.75 | 0.44 | −0.08 | 0.18 |

| Teased by other kids while physically active | 1.89 | 1.07 | 0.45 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.47 |

| Got out of breath | 2.49 | 1.08 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.14 | −0.11 | 0.23 |

| Found it hard to swing… | 1.49 | 0.86 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.37 |

| Problems fitting into your desk | 1.40 | 0.86 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| Chose not to go to school | 1.39 | 0.90 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 0.24 |

| Upset at mealtimes | 1.63 | 0.97 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Chose not to participate in gym | 1.55 | 1.01 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.14 |

| Did not want to go to the pool/park | 1.50 | 0.91 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.50 | −0.08 | 0.17 |

| Felt uncomfortable sleeping at friend’s house | 1.50 | 0.89 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.47 | −0.14 | 0.38 |

| Like yourself | 2.55 | 1.17 | −0.33 | −0.09 | −0.26 | 0.68 | −0.12 |

| Felt happy | 2.41 | 1.22 | −0.35 | −0.03 | −0.13 | 0.65 | −0.15 |

| Were told you are healthy | 2.61 | 1.06 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.47 | 0.16 |

| Felt you had a good sense of humor | 3.13 | 1.05 | 0.05 | −0.14 | −0.06 | 0.44 | −0.08 |

| Stood up for others | 2.60 | 1.15 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.07 |

| Were picked first | 2.04 | 1.19 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.16 |

| Felt left out | 1.85 | 1.09 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.78 |

| Teased by other kids | 2.03 | 1.12 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.55 |

Boldface text represents the factor loading of the item on its intended scale.

Table 3.

Reliabilities on Sizing Me Up

| Scale | Cronbach’s alpha |

Test–retest reliability (intraclass correlations) (n = 80) |

|---|---|---|

| Emotion | 0.85 | 0.66 |

| Physical | 0.76 | 0.74 |

| Social Avoidance | 0.70 | 0.53 |

| Positive Social Attributes | 0.68 | 0.74 |

| Teasing/Marginalization | 0.71 | 0.58 |

| Total Quality of Life | 0.82 | 0.78 |

Table 4.

Scale intercorrelations and convergence

| Sizing Me Up Scales | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion | Physical | Social Avoidance | Positive Social Attributes |

Teasing/ Marginalization |

Total QOL | |

| Sizing Me Up | ||||||

| Emotion | ||||||

| Physical | 0.54** | |||||

| Social Avoidance | 0.46** | 0.42** | ||||

| Positive Social Attributes | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.46** | |||

| Teasing/Marginalization | 0.58** | 0.56** | 0.05 | 0.01 | ||

| Total QOL | 0.79** | 0.75** | 0.68** | 0.48** | 0.68** | |

| PedsQL | ||||||

| Physical | 0.24** | 0.35** | 0.31** | 0.19* | 0.32** | 0.41** |

| Emotion | 0.35** | 0.33** | 0.24** | 0.07 | 0.36** | 0.38** |

| Social | 0.43** | 0.54** | 0.36** | 0.07 | 0.65** | 0.55** |

| School | 0.22** | 0.25** | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.30** | 0.27** |

| Psychosocial total | 0.42** | 0.48** | 0.30** | 0.10 | 0.56** | 0.51** |

| Total QOL | 0.39** | 0.47** | 0.33** | 0.14 | 0.52** | 0.52** |

Boldface values represent domains for which convergence was expected based on similarity of constructs.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01.

Scales assess children’s perceptions of the impact of their size on a specific age-salient domain: their feelings or emotions (Emotional Functioning), their ability to keep up with physical activities and teasing while being physically active (Physical Functioning), their comfort in and avoidance of social activities (Social Avoidance), their positive qualities and strengths (Positive Social Attributes), and whether they were teased or left out due to their weight (Teasing/Marginalization). The Total Quality of Life scale is a compilation of the five core scales. Scaled scores were calculated by summing the items and then transforming them to a score ranging from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the best HRQOL. The total score was calculated by summing all 22 items and then similarly transforming to a 0 to 100 scale.

Test–retest reliability

The average time between phase 1 and phase 2 visits was 17.0 days (s.d. = 7.6). There was no significant change in zBMI from phase 1 to 2 (paired t-test t (73) = 1.8; P = ns). Test–retest reliability was strong for a majority of scales, ranging from 0.53 to 0.78 (see Table 3).

Convergent validity and construct validity

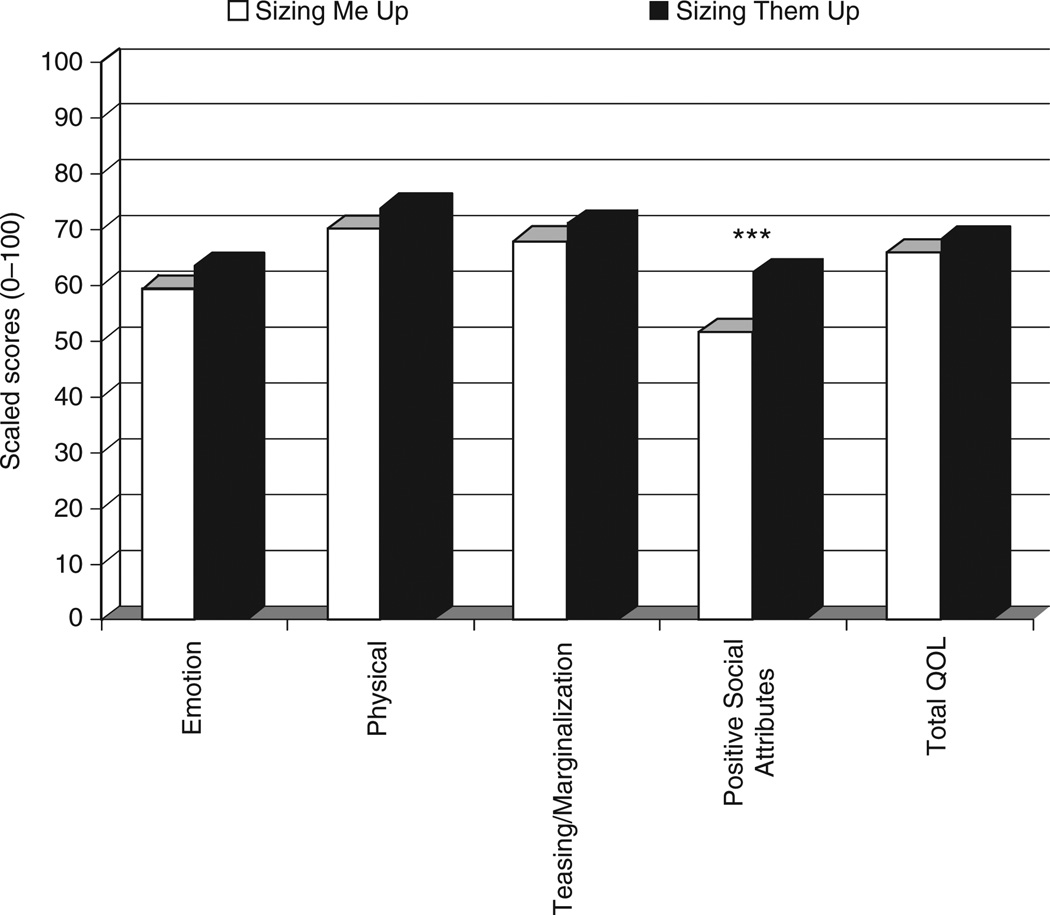

As expected, correlations were moderate and significant for similar domains of Sizing Me Up and the PedsQL (see Table 4). Correlations between similar scales on Sizing Me Up and the parent-proxy Sizing Them Up were small to moderate: Emotional Functioning (r = 0.22, P < 0.01), Physical Functioning (r = 0.27, P < 0.001), Teasing/Marginalization (r = 0.41, P < 0.001), Positive Attributes (r = 0.29, P < 0.01), and Total QOL scales (r = 0.44, P < 0.001). Significant differences between parent and child report were observed for the Positive Attributes scale (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Convergence between similar scales on Sizing Me Up and Sizing Them Up. ***t (140) = 5.03, P < 0.001.

Regarding the relation between Sizing Me Up and zBMI, higher zBMI was associated with poorer HRQOL for Emotional Functioning (r = 0.20, P = 0.02). A trend was noted for higher zBMI being associated with poorer HRQOL for Social Avoidance (r = 0.15, P = 0.07) and Total Quality of Life scale (r = 0.14, P = 0.095).

Race and gender differences

Race and gender differences were examined on Sizing Me Up scales, adjusting for zBMI scores. Given the large proportion of white and black youth in the current sample, analyses were limited to these two groups. The overall multivariate analysis of variance suggested significant race differences on Sizing Me Up scales (Hotelling’s T = 0.09, F (5, 126) = 2.29, P < 0.05). Post hoc analyses revealed black youth reported better Physical Functioning compared to white youth (Mblack = 74.7 vs. Mwhite= 65.5; F (1, 130) = 15.4, P < 0.05). Although the overall multivariate analysis of variance suggested significant gender differences on Sizing Me Up scales (Hotelling’s T = 0.09, F (1, 134) = 2.4, and P = 0.04), post hoc analyses revealed no significant gender differences on any one scale.

DISCUSSION

Sizing Me Up represents the first obesity-specific self-report HRQOL measure developed specifically for younger school-aged children (5–13 years). Preliminary results demonstrate that Sizing Me Up has strong psychometric properties, including good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent validity. Furthermore, these initial data demonstrate the feasibility of reliably and validly assessing the self-report of obesity-specific HRQOL in children as young as 5 years of age. Sizing Me Up is brief (22 items; 8–12 minutes completion time), easy to administer and score, of no-cost, and provides critical content to characterize the impact of children’s size on their daily functioning across a number of age-salient domains.

Sizing Me Up has five core scales (i.e., Emotional Functioning, Physical Functioning, Social Avoidance, Positive Social Attributes, and Teasing/Marginalization) and a Total score. The Emotional Functioning scale uniquely captures children’s self-perceptions of how their size makes them feel (i.e., mad, sad, worried, and frustrated). Although certainly there is a wide-range of assessment tools that measure a child’s more general emotional status, such as depression inventories (33), self-concept scales (34), and generic HRQOL measures (20), to our knowledge, this is the first measure for children that asks children to place their self-perceptions of emotions in the specific context of their obesity. Similarly, the Physical Functioning scale measures children’s self-perceptions of how much their size impacts their comfort and ability to engage in daily age-salient activities at school or within their community. In addition, this scale includes an item that targets weight-based teasing while being physically active, known to be predictive of lower physical activity levels in youth (35).

In terms of social relations, two scales emerged on Sizing Me Up. The Social Avoidance scale describes how their size may lead an obese child to avoid or feel discomfort in age-salient social settings (e.g., school, park, gym, sleepovers, and family meal). Alternately, the Teasing/Marginalization scale assesses children’s self-perceptions of feeling left out or teased by others due to their size, peer behaviors that are well documented in the pediatric obesity literature (36,37). Finally, the Positive Social Attributes scale encompasses child self-perceptions of positive qualities and emotions they possess in context of their size (e.g., humor, healthiness, happiness, and self-liking). We assert that the inclusion of an HRQOL scale focused on positive attributes may enable clinicians to understand a child’s self-perceived strengths, as well as areas that they may want to improve (24).

Additional analyses considered whether children’s self-reported, obesity-specific HRQOL varied by degree of obesity (zBMI), race (white, black), or gender. Within this clinically obese sample (BMI ≥ 95th percentile), higher zBMI was associated with poorer Emotional Functioning. Interesting trends also emerged suggesting higher zBMI is associated with greater Social Avoidance and lower overall obesity-specific quality of life (total score). Thus, these data provide initial evidence that children who have progressed to a greater degree of obesity in this young age range perceive greater HRQOL impairment due to their size. No significant gender differences were noted on Sizing Me Up and only one scale of this obesity-specific HRQOL measure was found to differ between black and white youth. Specifically, African American obese children reported better obesity-specific physical HRQOL than white children. Although we have previously documented that obese black adolescents are more physically comfortable with their size than whites when using a weight- or obesity-specific measure (12,18), these are the first data to characterize this in school-age children as young as 5 years of age.

As expected, Sizing Me Up demonstrated moderate agreement on similar scales of the PedsQL and the parallel parent-proxy, obesity-specific measure Sizing Them Up. Of note, Varni and colleagues (25) noted that imperfect agreement between child self-report and parent-proxy is consistently reported in the HRQOL literature. Used together, Sizing Me Up and Sizing Them Up offer researchers and/or clinical providers tools to assess both child and parent perspectives on how obesity is impacting a child’s daily life.

As noted, the present study represents an initial report on the psychometric properties of the Sizing Me Up measure. This study is not without limitations and consequent directions for future research. Specifically, the current sample may not be generalizable to all obese youth as (i) children and families were treatment seeking, (ii) data collection occurred at one site and while representative of the site’s clinic population, and (iii) children represented primarily two racial groups (e.g., white and black). Based on findings using a generic HRQOL measure (7), it is possible that obese children within the community who are not seeking treatment have better obesity-specific HRQOL compared to children seeking care in a clinical program. Future research with larger and more ethnically diverse samples of obese youth (e.g., Hispanic, Native American) is also needed. Furthermore, although this measure was intentionally developed and initially validated to assess self-perceptions of clinically obese (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) children, an important area of future study will be to evaluate the psychometric structure in an overweight population and to assess how Sizing Me Up differentiates child self-perceptions across the entire weight spectrum. Finally, although the present study presents key reliability and validity data of Sizing Me Up, an important next step will be to assess the measure’s responsiveness to change related to weight loss/gain to further establish Sizing Me Up as a well-validated patient-reported outcome measure.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health awarded to M.H.Z. (K23-DK60031) and a postdoctoral training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 DK063929) awarded to A.C.M. Additional resources were provided by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center–General Clinical Research Center, which is supported in part by US Public Health Service grant no. M01 RR 08084 from the General Clinical Research Centers Program, National Center for Research Resources/National Institutes of Health. We extend our thanks to the children and their families who participated in this study. We also thank the research assistants and summer students who were instrumental in recruiting participants and collecting data, including Christina Ramey, Lindsay Wilson, Carrie Piazza-Waggoner, Julie Koumoutsos, Sarah Valentine, Stephanie Ridel, Kate Grampp, Ambica Tumkur, Rachel Jordan, Matt Flanigan, and Neha Godiwala.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/oby

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA. 2008;299:2401–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow SE. Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeller MH, Modi AC. Psychosocial factors related to obesity in children and adolescents. In: Jelalian E, Steele RG, editors. Handbook of Child and Adolescent Obesity. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedlander SL, Larkin EK, Rosen CL, Palermo TM, Redline S. Decreased quality of life associated with obesity in school-aged children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:1206–1211. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravens-Sieberer U, Redegeld M, Bullinger M. Quality of life after in-patient rehabilitation in children with obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(Suppl 1):S63–S65. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. JAMA. 2003;289:1813–1819. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams J, Wake M, Hesketh K, Maher E, Waters E. Health-related quality of life of overweight and obese children. JAMA. 2005;293:70–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeller MH, Modi AC. Predictors of health-related quality of life in obese youth. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:122–130. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janicke DM, Marciel KK, Ingerski LM, et al. Impact of psychosocial factors on quality of life in overweight youth. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1799–1807. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. Impaired health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic conditions: a comparative analysis of 10 disease clusters and 33 disease categories/severities utilizing the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Beer M, Hofsteenge GH, Koot HM, et al. Health-related quality of life in obese adolescents is decreased and inversely related to BMI. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:710–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modi AC, Loux TJ, Bell SK, et al. Weight-specific health-related quality of life in adolescents with extreme obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2266–2271. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingerski LM, Janicke DM, Silverstein JH. Brief report: quality of life in overweight youth-the role of multiple informants and perceived social support. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:869–874. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fallon EM, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Norman AC, et al. Health-related quality of life in overweight and nonoverweight black and white adolescents. J Pediatr. 2005;147:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stern M, Mazzeo SE, Gerke CK, et al. Gender, ethnicity, psychosocial factors, and quality of life among severely overweight, treatment-seeking adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:90–94. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swallen KC, Reither EN, Haas SA, Meier AM. Overweight, obesity, and health-related quality of life among adolescents: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Pediatrics. 2005;115:340–347. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeller MH, Roehrig HR, Modi AC, Daniels SR, Inge TH. Health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in adolescents with extreme obesity presenting for bariatric surgery. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1155–1161. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolotkin RL, Zeller MH, Modi AC, et al. Assessing weight-related quality of life in adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:448–457. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinhas-Hamiel O, Singer S, Pilpel N, et al. Health-related quality of life among children and adolescents: associations with obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:267–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39:800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE. Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ): A User’s Manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. Assessing health-related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: first psychometric and content analytical results. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:399–407. doi: 10.1023/a:1008853819715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quittner AL, Davis MA, Modi AC. Health-related quality of life in pediatric populations. In: Roberts M, editor. Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. New York: Guilford Publications; 2003. pp. 696–709. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Modi AC, Zeller MH. Validation of a parent-proxy, obesity-specific quality-of-life measure: sizing them up. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2624–2633. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. How young can children reliably and validly self-report their health-related quality of life?: an analysis of 8,591 children across age subgroups with the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole TJ. The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1990;44:45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens G, Featherman DL. A revised socioeconomic index of occupational status. Soc Sci Res. 1981;10:364–395. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakao K, Treas J. The 1989 Socioeconomic Index of Occupations: Construction from the 1989 Occupational Prestige Scores. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, National Opinion Research Center; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hauser RM. Measuring socioeconomic status in studies of child development. Child Dev. 1994;65:1541–1545. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bryant F, Yarnold PR. Principal-component analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrout PE. Measurement reliability and agreement in psychiatry. Stat Methods Med Res. 1998;7:301–317. doi: 10.1177/096228029800700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harter S. The self-perception profile for children. Denver, CO: Department of Psychology, University of Denver; 1985. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faith MS, Leone MA, Ayers TS, Heo M, Pietrobelli A. Weight criticism during physical activity, coping skills, and reported physical activity in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 Pt 1):e23. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeller MH, Reiter-Purtill J, Ramey C. Negative peer perceptions of obese children in the classroom environment. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:755–762. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Storch EA, Milsom VA, DeBraganza N, et al. Peer victimization, psychosocial adjustment, and physical activity in overweight and at-risk-for-overweight youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:80–89. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.