Abstract

Background

Hyperprolactinemia is a common endocrine disorder that can be associated with significant morbidity. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analyses of outcomes of hyperprolactinemic patients, including microadenomas and macroadenomas, to provide evidence-based recommendations for practitioners. Through this review, we aimed to compare efficacy and adverse effects of medications, surgery and radiotherapy in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia.

Methods

We searched electronic databases, reviewed bibliographies of included articles, and contacted experts in the field. Eligible studies provided longitudinal follow-up of patients with hyperprolactinemia and evaluated outcomes of interest. We collected descriptive, quality and outcome data (tumor growth, visual field defects, infertility, sexual dysfunction, amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea and prolactin levels).

Results

After review, 8 randomized and 178 nonrandomized studies (over 3,000 patients) met inclusion criteria. Compared to no treatment, dopamine agonists significantly reduced prolactin level (weighted mean difference, -45; 95% confidence interval, -77 to −11) and the likelihood of persistent hyperprolactinemia (relative risk, 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.81 to 0.99). Cabergoline was more effective than bromocriptine in reducing persistent hyperprolactinemia, amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea, and galactorrhea. A large body of noncomparative literature showed dopamine agonists improved other patient-important outcomes. Low-to-moderate quality evidence supports improved outcomes with surgery and radiotherapy compared to no treatment in patients who were resistant to or intolerant of dopamine agonists.

Conclusion

Our results provide evidence to support the use of dopamine agonists in reducing prolactin levels and persistent hyperprolactinemia, with cabergoline proving more efficacious than bromocriptine. Radiotherapy and surgery are useful in patients with resistance or intolerance to dopamine agonists.

Keywords: Treatment, Hyperprolactinemia, Macroprolactinoma, Microprolactinoma

Background

Hyperprolactinemia is the most common disorder of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Patients typically present with hypogonadism, infertility or, in the case of macroadenomas, symptoms related to mass effect (headache and visual field defects).

In general, treatment of hyperprolactinemia, secondary to pituitary macroadenoma, is accepted as necessary. Medications in the form of dopamine agonists are the first line of treatment, with surgery and radiotherapy reserved for refractory and medication-intolerant patients [1]. The primary aim of treatment in patients with pituitary macroadenoma is to control compressive effects of the tumor, including compression of optic chiasm, with a secondary goal to restore gonadal function. However, indications and modalities of treatment of hyperprolactinemia due to pituitary microadenomas are less well defined [1]. Commonly cited indications for treatment of microprolactinomas include infertility, hypogonadism, prevention of bone loss and bothersome galactorrhea [1,2]. Treatment with dopamine agonists can restore normal prolactin levels and gonadal function. Dopamine agonists have been associated with various adverse effects including nausea, vomiting, psychosis and dyskinesia. However, the choice of which dopamine agonist is most efficacious and produces the least adverse effects is unclear.

To provide evidence-based recommendations to practicing clinicians facing these common therapeutic dilemmas, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analyses of the literature to evaluate outcomes and adverse effects with medications, surgery and radiotherapy in hyperprolactinemic patients. Outcomes of interest include prolactin levels, tumor size, and persistent hyperprolactinemia and patient-important outcomes, including visual disturbances, fertility, sexual dysfunction and galactorrhea,

Methods

The results are reported according to the PRISMA statement (Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) [3]. We used the relevant components of the Ottawa-Newcastle tool (whether cohorts represent clinical practice, blinding of outcome assessment, analysis adjustment for confounders, and adequacy of follow-up) [4] and the Cochrane risk of bias tool (extent of blinding, allocation concealment, and funding) to evaluate the quality of observational and randomized trials, respectively. Summary judgments about the quality of evidence for each outcome followed the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) framework (Additional file 1: Tables 2–4) [5].

Study eligibility

Eligible studies provided longitudinal follow-up data of cohorts of patients with hyperprolactinemia, that is, observational cohort studies or randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The outcomes of interest were tumor size, visual field defects, prolactin levels, galactorrhea, infertility, hypogonadism (amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea and low libido for premenopausal women, low libido or erectile dysfunction for men), bone density loss and fragility fracture rates, quality of life, and treatment adverse effects. We assumed author reports of “irregular menses” to mean amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea unless otherwise specified. We included studies with follow-up duration of at least six months and studies of at least 10 subjects. We did not impose any language restrictions.

Search strategy

We sought articles addressing hyperprolactinemia or prolactin-secreting tumors that were treated by dopamine agonists, surgery or radiotherapy, which focused on outcomes from those treatments. The search concepts of hyperprolactinemia, outcomes of interest (specific sequelae of amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea, sexual dysfunction, vision disorders, cranial nerve disorders and bone disorders), treatments and study design (observational longitudinal studies or RCTs) were represented in the search strategy using database-specific controlled vocabulary. We searched in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and the Ovid Cochrane Library, ISI Web of Science and Scopus from inception through September 2009. The search was updated on 15 December 2011. The complete search strategy was done with the help of an experienced research librarian and is available in the Additional file 1: Appendix.

Study selection

Study selection and data extraction procedures were conducted by pairs of reviewers working independently until adequate agreement (kappa ≥ 0.90) was obtained; then the process was conducted by single reviewers. First, eligibility criteria were applied to titles and abstracts, and potentially eligible studies were retrieved in full text. Then, eligibility criteria were applied to the full report. Disagreements were noted and resolved by discussion and consensus, erring on inclusion. We extracted descriptive data about enrolled patients, any treatment provided, study quality measures and outcome data from each study. Both study selection and data extraction were conducted using web-based software (Distiller SR, Ottawa, ON, Canada).

Statistical analysis

The effect size and the associated measures of precision were estimated from each study (relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes, weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous outcomes, and event rate for uncontrolled studies).

Effect sizes were pooled across studies using a random effects meta-analytical model [6]. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, which represents the proportion of between-study differences that are not attributable to chance or random error [7]. I2 values of <25%, 25 to 50% and >50% indicate mild, moderate and substantial heterogeneity, respectively. When meta-analysis includes less than three studies, the I2 is not calculable and is not reported. A priori planned subgroup interactions were based on sex and size of tumor (macro- vs. microprolactinomas). Median and range of event rates were estimated from uncontrolled cohort studies or case series that did not provide sufficient data for meta-analysis. All analyses were completed using Comprehensive Meta Analysis Version 2.2, Biostat, Englewood NJ (2005).

Results

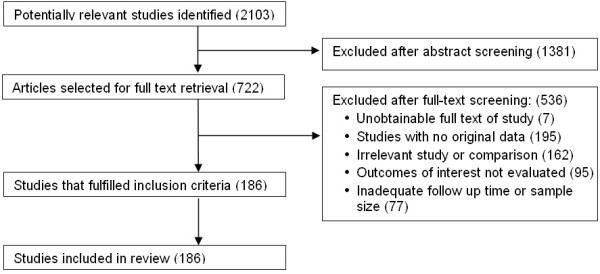

Literature search revealed 2,103 potentially relevant references, of which 189 were included (Figure 1). The description, quality assessment and bibliography of the studies are available in the Additional file 1: Appendix.

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

Twenty-nine studies were controlled (that is, two arms allowing for comparative analysis) (Additional file 1: Table 1), whereas 157 were uncontrolled (that is, the entire cohort received the same intervention allowing the estimation of event rates but no comparative analysis). We contacted the authors of the comparative studies via e-mail if possible and by postal mail if no e-mail was available; 20 authors replied, of which 15 confirmed or corrected study data.

Study quality

The quality of the observational studies was limited, with no blinding of outcome assessment and poor reporting of adjustments for confounders or other prognostic variables (Additional file 1: Tables 2 and 3). The quality of the eight RCTs [8-14] was fair (allocation was concealed in five; patients were blinded to assignment in six RCTs, caregivers in five) (Additional file 1: Table 4).

Patients treated with dopamine agonists

A large body of noncomparative cohort studies supported the use of dopamine agonists in patients with hyperprolactinemia. Those studies included: bromocriptine (n = 39); cabergoline (n = 26); and quinagolide (CV 205-502) (n = 15), which is not approved in the US. Bromocriptine studies had the longest follow-up (exceeding 10 years) and showed consistent benefits on several patient-important outcomes and surrogate outcomes (Additional file 1: Table 5A). Comparing across studies, 68% (median %) of patients treated with bromocriptine had normalization of prolactin levels and 62% experienced a reduction in tumor size. Bromocriptine also successfully treated other major outcomes, including 86% of patients with galactorrhea, 78% with amenorrhea, 67% with sexual dysfunction, 67% with visual field defects and 53% of patients with infertility. Studies of cabergoline and quinagolide showed similar results (Additional file 1: Tables 5B, C). In three observational studies that followed patients from 7 to 12 months, long-acting forms of bromocriptine were found to be as efficacious as the short-acting forms (Additional file 1: Table 5D). Other dopamine agonists typically used for other conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, were also used in this setting; namely, pergolide, lisuride, and roxindol (Additional file 1: Table 5E), with comparable findings.

A smaller body of evidence offers comparative effectiveness data from observational studies and eight RCTs. Forest plots depicting the results of these meta-analyses are in Additional file 1: Figures 1A-5B. The results are presented by comparison.

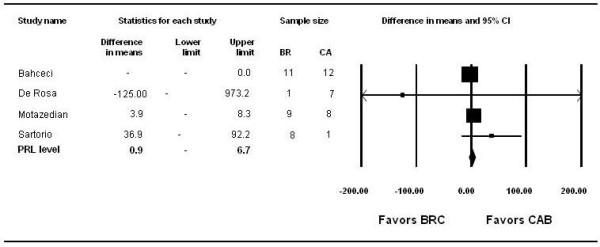

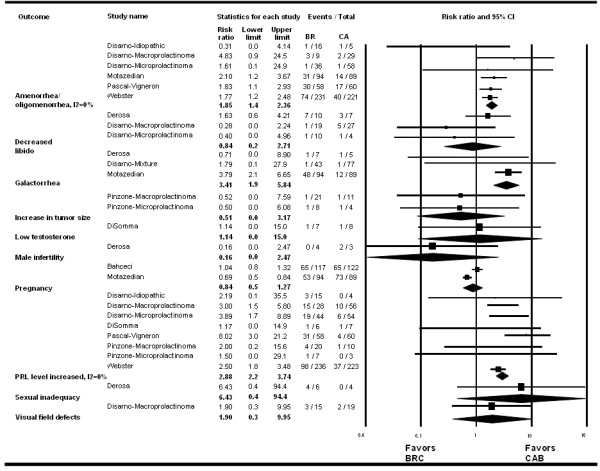

· Bromocriptine vs. Cabergoline (Figures 2 and 3): Six observational studies and three randomized trials compared bromocriptine to cabergoline. Bromocriptine was less effective than cabergoline in reducing the risk of persistent hyperprolactinemia (RR, 2.88; 95% CI, 2.20 to 3.74; I2 = 0%), amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea (RR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.40 to 2.36), and galactorrhea (RR, 3.41; 95% CI, 1.9 to 5.84). There were no significant differences between the two drugs in terms of overall change in prolactin level or other patient-important outcomes.

Figure 2.

Bromocriptine vs. Cabergoline: prolactin levels.

Figure 3.

Bromocriptine vs. Cabergoline: clinical outcomes.

· Bromocriptine vs. Quinagolide: Two observational studies and four RCTs compared quinagolide to bromocriptine. There were no significant differences between these agents across all outcomes reviewed (Additional file 1: Figures 1A and 1B).

· Dopamine agonists compared to no treatment: Three observational studies and one RCT compared dopamine agonists to no treatment. Dopamine agonists significantly reduced prolactin level (WMD, -45; 95% CI, -77 to -11) and the risk of persistent hyperprolactinemia (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.99) but not other patient-important outcomes (Additional file 1: Figures 2A and 2B).

· Comparison of dopamine agonists vs. surgery and combinations thereof: Additional file 1: Figures 3-5B depict comparisons between surgery vs. dopamine agonists, dopamine agonists vs. dopamine agonists + surgery, and surgery vs. surgery + dopamine agonists. The only significant difference among these comparisons was dopamine agonists were more effective in reducing the risk of persistent hyperprolactinemia compared to surgery alone.

The quality of evidence in this comparison for all outcomes is very low due to methodological limitations of included studies and the serious imprecision of meta-analytic estimates that include both trivial and large effects. Subgroup analyses for these comparisons (Additional file 1: Table 6) did not reveal a significant interaction based on sex or tumor size (macro- vs. microprolactinoma).

Patients treated with other modalities

Other treatments, such as radiotherapy, surgery and combinations of treatments were evaluated in an uncontrolled series of patients. Meta-analysis was not conducted due to the significant clinical heterogeneity in terms of patient characteristics and symptomatology as well as the heterogeneity of study settings, design and follow-up duration.

Radiotherapy was evaluated in eight studies with follow-up of at least two years. In patients with medically and surgically refractory prolactinomas, radiotherapy produced a reduction in prolactin levels in nearly all patients and normalization in over a quarter of patients with low complication rates (Additional file 1: Table 7A). External and implanted radiotherapy methods were also used in conjunction with dopamine agonists and resulted in significant improvement in prolactin levels, visual symptoms and fertility (four studies with follow-up of between 12 and 140 months, Additional file 1: Table 7B).

Trans-sphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenomas was evaluated in 27 uncontrolled studies (Additional file 1: Table 7C) and was found to be effective in normalizing prolactin levels and resolving symptoms. Patients opting for this approach had often failed other management options and may have had a worse prognosis that was independent of the treatment; this selection bias may underestimate the effectiveness of surgery. In five studies, a combination of surgery and dopamine agonists achieved high rates of prolactin normalization and had relatively low rates of recurrence (Additional file 1: Table 7D). In two studies (Additional file 1: Table 7E), surgery combined with radiotherapy was also seen to be effective.

Adverse effects

Commonly reported side effects for all dopamine agonists included nausea, dizziness, postural hypotension and headache. In studies comparing cabergoline and bromocriptine, side effects were less frequent and milder with cabergoline compared to bromocriptine. In one study, 18%, 18%, 9% and 3% of patients experienced nausea, hypotension, headache and vomiting, respectively, compared with 44 21%, 27% and 20% in patients receiving bromocriptine [Motazedian, 2010, #105]. Bahceci found an overall side effect rate of 2.5% for cabergoline versus 15.3% for bromocriptine [Bahceci, 2010, #103]. Another study found a 29% overall side effect rate for cabergoline vs. 70% with bromocriptine, and that cabergoline side effects were more mild, self-limited, and did not require intervention, compared to bromocriptine side effects which required dose reduction and intervention in 29% of cases [De Rosa, 1998, #104]. Non-comparative studies revealed similar findings with the most common side effects of dopamine agonists being nausea, vomiting, headache, hypotension, with rare side effects of rhinorrhea and hypotonia. Adverse effects reported with transsphenoidal surgery included cerebrospinal fluid leak, diabetes insipidus, rhinorrhea and hypopituitarism, while radiotherapy was associated with nausea, headache, visual disturbances and hearing loss.

Pregnancy studies

Twenty studies followed pregnant women and their offspring from 6 months up to 12 years (Additional file 1: Table 7F). A fairly consistent finding was that there was no significant increase in the risk of obstetric complications, miscarriages, fetal malformation or other pregnancy outcomes, even if they had been treated with dopamine agonists to induce ovulation. The quality of this evidence is low considering the lack of contemporary untreated control groups in most studies or the enrollment of nonconsecutive samples of patients.

Discussion

The two most commonly prescribed drugs in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia are bromocriptine and cabergoline. Both medications are dopamine receptor agonists and share many characteristics and adverse effects, such as headache, nausea and vomiting, among others, though frequency and severity of adverse effects appears to be less in cabergoline compared to bromocriptine. Previous concerns about valvular heart disease [15,16] with the use of these agents have largely been disproved by more recent reports [17-19]. Our review demonstrated that cabergoline was significantly better than bromocriptine in decreasing the risks of persistent hyperprolactinemia, amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea and galactorrhea. Frequency of dosing may also affect treatment decisions as cabergoline is dosed twice weekly, whereas bromocriptine is given daily. However, cabergoline costs at least twice as much as bromocriptine and was not found to be superior in other outcomes. Though both drugs have been found to be safe in pregnancy, the number of reports studying bromocriptine in pregnancy far exceeds that of cabergoline in pregnancy.

A large body of moderate quality evidence from observational studies supports the use of dopamine agonists to normalize prolactin levels and resolve the symptoms related to mass effect and elevated prolactin levels. The large treatment effect of dopamine agonists, the potential dose response effect, biological plausibility, temporality between treatment and effect, consistency across studies, settings and methods, and coherence (consistency across agents within the same class), strongly support the effectiveness of these treatment agents in reducing prolactin levels and improving symptoms [20]. In addition, the recurrence of hyperprolactinemia after withdrawal of dopamine agonists strengthens the inference about causality (that is, challenge-rechallenge phenomenon). Clinicians using these medications are well aware of potential adverse effects that sometimes limit use, which include nausea, vomiting, psychosis and dyskinesia, among others.

Efficacy of surgery and radiotherapy in selected patients is also substantiated, although by low-to-moderate quality evidence at higher risk of bias. Radiotherapy and surgery appear to be efficacious in patients with resistance or intolerance to dopamine agonists. However, surgery as a primary therapy has also been described in a recent consecutive series of 212 patients with prolactinomas [21]. This study reports high short-term remission rates, particularly in patients with microadenomas and cystic tumors. Besides the usual surgical risks, hypopituitarism is a potential long-term effect of both radiotherapy and surgery and should be discussed with patients as part of the decision-making process.

Comparison with previous reviews, strengths and limitations

Only a few previous systematic reviews have been published in this field, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first to comprehensively address the efficacy questions outlined in our protocol. Our work is also referenced as unpublished data in the 2011 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline: Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyperprolactinemia [22]. Our results are similar to other reviews, including Dekkers’ meta-analysis of the sustainability of normoprolactinemia after treatment withdrawal, which found recurrences in a substantial proportion of patients [23], and Dos Santos Nunes’ systematic review and meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials, which demonstrated that normalization of prolactin levels and menstruation favored cabergoline compared to bromocriptine [24].

The strengths of our review include the comprehensive nature of the literature search, the immediate relevancy of the questions at hand to decision making, and the adoption of bias protection measures that included contacting the authors of the included studies. Limitations to the inferences presented in this report relate to the overall low quality of evidence due to the methodological limitations of the included studies, and by the imprecision and heterogeneity in the results. Also, this evidence is at high risk of publication and reporting biases, both of which are more likely when the evidence consists of mostly small RCTs and observational studies. Inferences should also be limited considering the frequent use of the surrogate outcome, prolactin level, as opposed to patient-important outcomes [25], such as loss of quality of life due to tumor-related and hypogonadal symptoms.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analyses affirm the use of dopamine agonists in treating hyperprolactinemia and reducing associated morbidity. Cabergoline was found to be more effective than bromocriptine in achieving normoprolactinemia and resolving amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea and galactorrhea. Radiotherapy and surgery are efficacious in patients with resistance or intolerance to dopamine agonists.

Abbreviations

PRISMA, Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses; RCT, Randomized controlled trial; RR, Relative risk; WMD, Weighted mean difference.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ATW, PJE, GYG, VMM and MHM were responsible for the study’s conception and design. ATW, RJM, MAL, AH, CP, NWG, MMF, AB, FC, JC, TAE and, PJE acquired the data. ATW, RJM, MAL, TAE and MHM analyzed and interpreted the data. All the authors were responsible for drafting, critical revisions, and final approval of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially funded by the Endocrine Society.

Supplementary Material

Appendix. Treatment of hyperprolactinemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Description of data: Contents: Baseline characteristics of the included comparative studies (Supplemental Table 1), Quality of the included observational comparative studies (Supplemental Table 2), Quality of the included observational dopamine withdrawal studies (Supplemental Table 3), Quality of randomized trials (Supplemental Table 4), Summary of uncontrolled studies of dopamine agonists (Supplemental Tables 5A-E), Meta-analyses figures (Supplemental Figures 1A-5B), Subgroup analyses (Supplemental Tables 6A-D), Summary of uncontrolled studies of radiotherapy, surgery, combinations of treatment, and pregnancy (Supplemental Tables 7A-F), References, Search strategy [26-205].

Contributor Information

Amy T Wang, Email: wang.amy@mayo.edu.

Rebecca J Mullan, Email: mullan.rebecca@gmail.com.

Melanie A Lane, Email: melanielane7@gmail.com.

Ahmad Hazem, Email: adhazem@yahoo.com.

Chaithra Prasad, Email: prasad.chaithra@mayo.edu.

Nicola W Gathaiya, Email: gathaiya.nicola@mayo.edu.

M Mercè Fernández-Balsells, Email: mercefernandez.girona.ics@gencat.cat.

Amy Bagatto, Email: aimsjoy@gmail.com.

Fernando Coto-Yglesias, Email: cotoyglesias@yahoo.com.

Jantey Carey, Email: janteycarey@gmail.com.

Tarig A Elraiyah, Email: elraiyah.tarig@mayo.edu.

Patricia J Erwin, Email: erwin.patricia@mayo.edu.

Gunjan Y Gandhi, Email: gandhi.gunjan@mayo.edu.

Victor M Montori, Email: montori.victor@mayo.edu.

Mohammad Hassan Murad, Email: murad.mohammad@mayo.edu.

References

- Casanueva FF, Molitch ME, Schlechte JA, Abs R, Bonert V, Bronstein MD, Brue T, Cappabianca P, Colao A, Fahlbusch R. et al. Guidelines of the Pituitary Society for the diagnosis and management of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;65:265–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam M, Molitch M, Lombardi G, Colao A. Advances in the treatment of prolactinomas. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:485–534. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-9998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm]

- Swiglo BA, Murad MH, Schunemann HJ, Kunz R, Vigersky RA, Guyatt GH, Montori VM. A case for clarity, consistency, and helpfulness: state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines in endocrinology using the grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:666–673. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirahara F, Andoh N, Sawai K, Hirabuki T, Uemura T, Minaguchi H. Hyperprolactinemic recurrent miscarriage and results of randomized bromocriptine treatment trials. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:246–252. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homburg R, West C, Brownell J, Jacobs HS. A double-blind study comparing a new non-ergot, long-acting dopamine agonist, CV 205-502, with bromocriptine in women with hyperprolactinaemia. Clin Endocrinol. 1990;32:565–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappohn RE, van de Wiel HB, Brownell J. The effect of two dopaminergic drugs on menstrual function and psychological state in hyperprolactinemia. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:321–327. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal-Vigneron V, Weryha G, Bosc M, Leclere J. Hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea:treatment with cabergoline versus bromocriptine. Results of a national multicenter randomized double-blind study. Presse Med. 1995;24:753–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden PF, de Wit W, Brownell J, Schoemaker J, Rolland R. CV 205-502, a new dopamine agonist, versus bromocriptine in the treatment of hyperprolactinaemia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991;40:111–118. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90101-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhelst JA, Froud AL, Touzel R, Wass JA, Besser GM, Grossman AB. Acute and long-term effects of once-daily oral bromocriptine and a new long-acting non-ergot dopamine agonist, quinagolide, in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia: a double-blind study. Acta Endocrinol. 1991;125:385–391. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1250385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J, Piscitelli G, Polli A, Ferrari C, Ismail I, Scanlon M. A comparison of cabergoline and bromocriptine in the treatment of hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea. Cabergoline Comparative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:904–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motazedian S, Babakhani L, Fereshtehnejad SM, Mojtahedi K. A comparison of bromocriptine & cabergoline on fertility outcome of hyperprolactinemic infertile women undergoing intrauterine insemination. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:670–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahceci M, Sismanoglu A, Ulug U. Comparison of cabergoline and bromocriptine in patients with asymptomatic incidental hyperprolactinemia undergoing ICSI-ET. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:505–508. doi: 10.3109/09513591003632233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa M, Colao A, Di Sarno A, Ferone D, Landi ML, Zarrilli S, Paesano L, Merola B, Lombardi G. Cabergoline treatment rapidly improves gonadal function in hyperprolactinemic males: a comparison with bromocriptine. Eur. 1998;138:286–293. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1380286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath J, Fross RD, Kleiner-Fisman G, Lerch R, Stalder H, Liaudat S, Raskoff WJ, Flachsbart KD, Rakowski H, Pache JC. et al. Severe multivalvular heart disease: a new complication of the ergot derivative dopamine agonists. Mov Disord. 2004;19:656–662. doi: 10.1002/mds.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascol O, Pathak A, Bagheri H, Montastruc JL. New concerns about old drugs: Valvular heart disease on ergot derivative dopamine agonists as an exemplary situation of pharmacovigilance. Mov Disord. 2004;19:611–613. doi: 10.1002/mds.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafeber M, Stades AME, Valk GD, Cramer MJ, van Berkhout FT, Zelissen PMJ. Absence of major fibrotic adverse events in hyperprolactinemic patients treated with cabergoline. Eur. 2010;162:667–675. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan T, Cabrita IZ, Hensman D, Grogono J, Dhillo WS, Baynes KC, Eliahoo J, Meeran K, Robinson S, Nihoyannopoulos P, Martin NM. Assessment of cardiac valve dysfunction in patients receiving cabergoline treatment for hyperprolactinaemia. Clin Endocrinol. 2010;73:369–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valassi E, Klibanski A, Biller BM. Clinical Review#: Potential cardiac valve effects of dopamine agonists in hyperprolactinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1025–1033. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Rawlins M, McCulloch P. When are randomised trials unnecessary? Picking signal from noise. BMJ. 2007;334:349–351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39070.527986.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzer J, Buslei R, Wallaschofski H, Hofmann B, Nimsky C, Fahlbusch R, Buchfelder M. Operative treatment of prolactinomas: indications and results in a current consecutive series of 212 patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:11–18. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Hoffman AR, Kleinberg DL, Montori VM, Schlechte JA, Wass JA. Diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:273–288. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers O, Lagro J, Burman P, Jørgensen J, Romijn J, Pereira A. Recurrence of hyperprolactinemia after withdrawal of dopamine agonists: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:43–51. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos Nunes V, El Dib R, Boguszewski CL, Nogueira CR. Cabergoline versus bromocriptine in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. Pituitary. 2011;14:259–265. doi: 10.1007/s11102-010-0290-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi GY, Murad MH, Fujiyoshi A, Mullan RJ, Flynn DN, Elamin MB, Swiglo BA, Isley WL, Guyatt GH, Montori VM. Patient-important outcomes in registered diabetes trials. JAMA. 2008;299:2543–2549. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano S, Ueki K, Suzuki I, Kirino T. Clinical features and medical treatment of male prolactinomas. Acta Neurochir. 2001;143:465–470. doi: 10.1007/s007010170075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brue T, Pellegrini I, Priou A, Morange I, Jaquet P. Prolactinomas and resistance to dopamine agonists. Horm Res. 1992;38:84–89. doi: 10.1159/000182496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candrina R, Galli G, Bollati A, Pizzocolo G, Orlandini A, Gualandi GF, Giustina G. Results of combined surgical and medical therapy in patients with prolactin-secreting pituitary macroadenomas. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:894–897. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198712000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Merola B, Sarnacchiaro F, Di Sarno A, Landi ML, Marzullo P, Cerbone G, Ferone D, Lombardi G. Comparison among different dopamine-agonists of new formulation in the clinical management of macroprolactinomas. Horm Res. 1995;44:222–228. doi: 10.1159/000184630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sarno A, Landi ML, Cappabianca P, Di Salle F, Rossi FW, Pivonello R, Di Somma C, Faggiano A, Lombardi G, Colao A. Resistance to cabergoline as compared with bromocriptine in hyperprolactinemia: prevalence, clinical definition, and therapeutic strategy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5256–5261. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.11.5256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Somma C, Colao A, Di Sarno A, Klain M, Landi ML, Facciolli G, Pivonello R, Panza N, Salvatore M, Lombardi G. Bone marker and bone density responses to dopamine agonist therapy in hyperprolactinemic males. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:807–813. doi: 10.1210/jc.83.3.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt G, Bauer T, Stracke H, Fassbender WJ, Mueller HW, Agnoli AL, Federlin K, Roosen K. Surgery, dopamine agonist therapy of combined treatment–results in prolactinoma patients after a 12 month follow-up. Zentralbl Neurochir. 1992;53:123–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcoate WJ, Pound N, Sturrock ND, Lambourne J. Long-term follow-up of patients with hyperprolactinaemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996;45:299–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood IH, Al-Husaynei AJ, Mohamad SH. Comparative effects of bromocriptine and cabergoline on serum prolactin levels, liver and kidney function tests in hyperprolactinemic women. Pak J Med Sci. 2010;26:255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Mattei AM, Severini V, Crosignani PG. Natural history of hyperprolactinemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;626:130–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin G, Treluyer C, Trouillas J, Sassolas G, Goutelle A. Surgical outcome and pathological effects of bromocriptine preoperative treatment in prolactinomas. Pathol Res Pract. 1991;187:587–592. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzone JJ, Katznelson L, Danila DC, Pauler DK, Miller CS, Klibanski A. Primary medical therapy of micro- and macroprolactinomas in men.[see comment] J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3053–3057. doi: 10.1210/jc.85.9.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush S, Donahue B, Cooper P, Lee C, Persky M, Newall J. Prolactin reduction after combined therapy for prolactin macroadenomas. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:502–505. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199104000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaan NA, Schultz PN, Leavens TA, Leavens ME, Lee YY. Pregnancy after treatment in patients with prolactinoma: operation versus bromocriptine. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:1300–1305. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorio A, Conti A, Ambrosi B, Muratori M, Morabito F, Faglia G. Osteocalcin levels in patients with microprolactinoma before and during medical treatment. J Endocrinol Invest. 1990;13:419–422. doi: 10.1007/BF03350694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih CJ, Tsou CK, Chiu WT, Tsai SH. Management of prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas with surgery and bromocriptine. Southeast Asian J Surg. 1983;6:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sluijmer AV, Lappohn RE. Clinical history and outcome of 59 patients with idiopathic hyperprolactinemia. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:72–77. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres I, Carral F, Vilchez F, Gavilán J, Aguilar M. Clinical, radiologic, and follow-up findings in patients with macroprolactinoma. Endocrinologist. 2006;16:241–244. doi: 10.1097/01.ten.0000240933.97458.bf. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Touraine P, Plu-Bureau G, Beji C, Mauvais-Jarvis P, Kuttenn F. Long-term follow-up of 246 hyperprolactinemic patients. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:162–168. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.080002162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J, Piscitelli G, Polli A, Ferrari CI, Ismail I, Scanlon MF. A comparison of cabergoline and bromocriptine in the treatment of hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea. Cabergoline Comparative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:904–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas M, Smith J, Jadon D, McEwan P, Rees DA, Evans LM, Scanlon MF, Davies JS. Long-term remission following withdrawal of dopamine agonist therapy in subjects with microprolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;63:26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannavo S, Curto L, Squadrito S, Almoto B, Vieni A, Trimarchi F. Cabergoline: a first-choice treatment in patients with previously untreated prolactin-secreting pituitary adenoma. J Endocrinol Invest. 1999;22:354–359. doi: 10.1007/BF03343573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli E, Grottoli S, Razzore P, Gaia D, Bertagna A, Cirillo S, Cammarota T, Camanni M, Camanni F. Long-term treatment with cabergoline, a new long-lasting ergoline derivate, in idiopathic or tumorous hyperprolactinaemia and outcome of drug-induced pregnancy. J Endocrinol Invest. 1997;20:547–551. doi: 10.1007/BF03348017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Di Sarno A, Cappabianca P, Di Somma C, Pivonello R, Lombardi G. Withdrawal of long-term cabergoline therapy for tumoral and nontumoral hyperprolactinemia.[see comment] N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2023–2033. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corenblum B, Taylor PJ. Idiopathic hyperprolactinemia may include a distinct entity with a natural history different from that of prolactin adenomas. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:544–546. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59790-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sarno A, Landi ML, Marzullo P, Di Somma C, Pivonello R, Cerbone G, Lombardi G, Colao A. The effect of quinagolide and cabergoline, two selective dopamine receptor type 2 agonists, in the treatment of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000;53:53–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eversmann T, Fahlbusch R, Rjosk HK, von Werder K. Persisting suppression of prolactin secretion after long-term treatment with bromocriptine in patients with prolactinomas. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1979;92:413–427. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0920413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock KW, Scott JS, Lamb JT, Gibson RM, Chapman C. Long term suppression of prolactin concentrations after bromocriptine induced regression of pituitary prolactinomas. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:117–118. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6462.117-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston DG, Prescott RW, Kendall-Taylor P, Hall K, Crombie AL, Hall R, McGregor A, Watson MJ, Cook DB. Hyperprolactinemia. Long-term effects of bromocriptine. Am J Med. 1983;75:868–874. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharlip J, Salvatori R, Yenokyan G, Wand GS. Recurrence of hyperprolactinemia after withdrawal of long-term cabergoline therapy.[see comment] J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2428–2436. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liuzzi A, Dallabonzana D, Oppizzi G, Verde GG, Cozzi R, Chiodini P, Luccarelli G. Low doses of dopamine agonists in the long-term treatment of macroprolactinomas. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:656–659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509123131103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattei AM, Ferrari C, Ragni G, Benco R, Picciotti MC, Rampini P, Caldara R, Crosignani PG. Serum prolactin and ovarian function after discontinuation of drug treatment for hyperprolactinaemia: a study with bromocriptine and metergoline. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:244–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb04761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriondo P, Travaglini P, Nissim M, Conti A, Faglia G. Bromocriptine treatment of microprolactinomas: evidence of stable prolactin decrease after drug withdrawal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60:764–772. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-4-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratori M, Arosio M, Gambino G, Romano C, Biella O, Faglia G. Use of cabergoline in the long-term treatment of hyperprolactinemic and acromegalic patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 1997;20:537–546. doi: 10.1007/BF03348016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos VQ, Souza JJ, Musolino NR, Bronstein MD. Long-term follow-up of prolactinomas: normoprolactinemia after bromocriptine withdrawal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3578–3582. doi: 10.1210/jc.87.8.3578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartagni M, Nicastri PL, Diaferia A, Di Gesu I, Loizzi P. Long-term follow-up of women with amenorrhea-galactorrhea treated with bromocriptine. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1995;22:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van 't Verlaat JW, Croughs RJ. Withdrawal of bromocriptine after long-term therapy for macroprolactinomas; effect on plasma prolactin and tumour size.[see comment] Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1991;34:175–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1991.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann W, Allolio B, Deuss U, Heesen D, Kaulen D. In: Basic and Clinical Correlates. Macleod RM, Thorner MO, Scapagnini U, editor. Liviana Press, Padova; 1985. Persisting normoprolactinemia after withdrawal of bromocriptine long-term therapy in patients with prolactinomas; pp. 817–822. [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZB, Yu CJ, Su ZP, Zhuge QC, Wu JS, Zheng WM. Bromocriptine treatment of invasive giant prolactinomas involving the cavernous sinus: results of a long-term follow up. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:54–61. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate A, Canales ES, Cano C, Pilonieta CJ. Follow-up of patients with prolactinomas after discontinuation of long-term therapy with bromocriptine. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1983;104:139–142. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1040139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Suleiman SA, Najashi S, Rahman J, Rahman MS. Outcome of treatment with bromocriptine in patients with hyperprolactinaemia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;29:176–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1989.tb01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergh T, Nillius J, Wide L. Bromocriptine treatment of 42 hyperprolactinaemic women with secondary amenorrhoea. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1978;88:435–451. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0880435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brue T, Lancranjan I, Louvet JP, Dewailly D, Roger P, Jaquet P. A long-acting repeatable form of bromocriptine as long-term treatment of prolactin-secreting macroadenomas: a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannavo S, De Natale R, Curto L, Li Calzi L, Trimarchi F. Effectiveness of computer-assisted perimetry in the follow-up of patients with pituitary microadenoma responsive to medical treatment. Clin Endocrinol. 1992;37:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay A, Bhansali A, Masoodi SR. Long-term efficacy of bromocriptine in macroprolactinomas and giant prolactinomas in men. Pituitary. 2005;8:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s11102-005-5111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corenblum B, Taylor PJ. Long-term follow-up of hyperprolactinemic women treated with bromocriptine. Fertil Steril. 1983;40:596–599. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)47415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinos JJ, Rodriguez-Espinosa J, Webb SM, Calaf-Alsina J. Long-acting repeatable bromocriptine in the treatment of patients with microprolactinoma intolerant or resistant to oral dopaminergics. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:926–931. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essais O, Bouguerra R, Hamzaoui J, Marrakchi Z, Hadjri S, Chamakhi S, Zidi B, Ben Slama C. Efficacy and safety of bromocriptine in the treatment of macroprolactinomas. Ann Endocrinol. 2002;63:524–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsetti L, Zanagnolo V, Gastaldi A. A retrospective study of idiopathic hyperprolactinemias. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1988;43:1063–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Fletes Rabago VM, Torres Farias S, Dominguez Jimenez A, Padilla Ruiz R. [Alternative to bromocriptine (BEC) management in patients with prolactinoma and intolerance to oral BEC] Ginecol Obstet Mex. 1991;59:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan SL, Oppenheim DS, Klibanski A. Importance of gonadal steroids to bone mass in men with hyperprolactinemic hypogonadism. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:526–531. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-7-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase R, Jaspers C, Schulte HM, Lancranja I, Pfingsten H, Orri-Fend M, Reinwein D, Benker G. Control of prolactin-secreting macroadenomas with parenteral, long-acting bromocriptine in 30 patients treated for up to 3 years. Clin Endocrinol. 1993;38:165–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp W, Nagel GA. Bromocriptine with chemotherapy resistant, metastatic breast cancer. Results of the AIO-Study GO-MC-BROMO 2/82. Onkologie. 1988;11:121–127. doi: 10.1159/000216502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamrozik SI, Bennet AP, James-Deidier A, Tremollieres F, Saint-Martin F, Dumoulin S, Valat-Coustols M, de Glisezinski I, Tremoulet M, Manelfe C, Louvet JP. Treatment with long acting repeatable bromocriptine (Parlodel-LAR*) in patients with macroprolactinomas: long-term study in 29 patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 1996;19:472–479. doi: 10.1007/BF03349893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengyel AM, Mussio W, Imamura P, Vieira JG, Lancranjan I. Long-acting injectable bromocriptine (Parlodel LAR) in the chronic treatment of prolactin-secreting macroadenomas. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:980–987. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55914-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SQ. Experiences with bromocriptine treatment of female infertility due to hyperprolactinemia. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 1992;27:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg E, af Trampe E, Wersall J, Werner S. Long-term effects of radiotherapy and bromocriptine treatment in patients with previous surgery for macroprolactinomas. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:200–204. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199108000-00005. discussion 204-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraschini C, Moro M, Masala A, Toja P, Alagna S, Brunani A, Rovasio PP, Ginanni A, Lancranjan I, Cavagnini F. Chronic treatment with parlodel LAR of patients with prolactin-secreting tumours. Different responsiveness of micro- and macroprolactinomas. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1991;125:494–501. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1250494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merola B, Colao A, Caruso E, Sarnacchiaro F, Lancranjan I, Lombardi G, Schettini G. Effectiveness and long-term tolerability of the slow release oral form of bromocriptine on tumoral and non-tumoral hyperprolactinemia. J Endocrinol Invest. 1992;15:173–176. doi: 10.1007/BF03348700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molitch ME, Elton RL, Blackwell RE, Caldwell B, Chang RJ, Jaffe R, Joplin G, Robbins RJ, Tyson J, Thorner MO. Bromocriptine as primary therapy for prolactin-secreting macroadenomas: results of a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60:698–705. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-4-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mornex R, Orgiazzi J, Hugues B, Gagnaire JC, Claustrat B. Normal pregnancies after treatment of hyperprolactinemia with bromoergocryptine, despite suspected pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;47:290–295. doi: 10.1210/jcem-47-2-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro M, Maraschini C, Toja P, Masala A, Alagna S, Rovasio PP, Ginanni A, Lancranjan I, Cavagnini F. Comparison between a slow-release oral preparation of bromocriptine and regular bromocriptine in patients with hyperprolactinemia: a double blind, double dummy study. Horm Res. 1991;35:137–141. doi: 10.1159/000181889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti AM, Cagnacci A, Mais V, Ajossa S, Guerriero S, Murgia C, Depau GF, Serra GG, Melis GB. Shrinkage of pituitary PRL-secernent adenoma after short-term treatment with bromocriptine long-acting repeatable injections. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1994;21:124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen C, Larsson SG, Bergh T. Long-term radiographic follow-up of the sella turcica in hyperprolactinaemic women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;30:257–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1990.tb03228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schettini G, Lombardi G, Merola B, Colao A, Miletto P, Caruso E, Lancranjan I. Rapid and long-lasting suppression of prolactin secretion and shrinkage of prolactinomas after injection of long-acting repeatable form of bromocriptine (Parlodel LAR) Clin Endocrinol. 1990;33:161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrabanek P, McDonald D, De Valera E. Plasma prolactin in amenorrhoea, infertility, and other disorders: A retrospective study of 608 patients. Ir J Med Sci. 1980;149:236–245. doi: 10.1007/BF02939147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spark RF, Baker R, Bienfang DC, Bergland R. Bromocriptine reduces pituitary tumor size and hypersection. Requiem for pituitary surgery? JAMA. 1982;247:311–316. doi: 10.1001/jama.1982.03320280031025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorner MO, Besser GM. Bromocriptine treatment of hyperprolactinaemic hypogonadism. Acta Endocrinol Suppl. 1978;216:131–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsagarakis S, Tsiganou E, Tzavara I, Nikolou H, Thalassinos N. Effectiveness of a long-acting injectable form of bromocriptine in patients with prolactin and growth hormone secreting macroadenomas. Clin Endocrinol. 1995;42:593–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van 't Verlaat JW, Croughs RJ, Hendriks MJ, Bosma NJ, Nortier JW, Thijssen JH. Bromocriptine treatment of prolactin secreting macroadenomas: a radiological, ophthalmological and endocrinological study. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1986;112:487–493. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1120487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JP, Pullan PT. Hyperprolactinaemia in males: a heterogeneous disorder. Aust N Z J Med. 1997;27:385–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1997.tb02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wass JA, Williams J, Charlesworth M, Kingsley DP, Halliday AM, Doniach I, Rees LH, McDonald WI, Besser GM. Bromocriptine in management of large pituitary tumours. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284:1908–1911. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6333.1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingrill CO, Mussio W, Moraes CR, Portes E, Castro RC, Lengyel AM. Long-acting oral bromocriptine (Parlodel SRO) in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:331–335. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54840-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MS, Hong JW, Lee SK, Lee EJ, Kim SH. Clinical management and outcome of 36 invasive prolactinomas treated with dopamine agonist. J Neurooncol. 2011;104:195–204. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhansali A, Walia R, Dutta P, Khandelwal N, Sialy R, Bhadada S. Efficacy of cabergoline on rapid escalation of dose in men with macroprolactinomas. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:530–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biller BMK, Molitch ME, Vance ML, Cannistraro KB, Davis KR, Simons JA, Schoenfelder JR, Klibanski A. Treatment of prolactin-secreting macroadenomas with the once-weekly dopamine agonist cabergoline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2338–2343. doi: 10.1210/jc.81.6.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolko P, Jaskula M, Wasko R, Wolun M, Sowinski J. The assessment of cabergoline efficacy and tolerability in patients with pituitary prolactinoma type. Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej. 2003;109:489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyukbayrak EE, Karageyim Karsidag AY, Kars B, Balcik O, Pirimoglu M, Unal O, Turan C. Effectiveness of short-term maintenance treatment with cabergoline in microadenoma-related and idiopathic hyperprolactinemia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;282:561–566. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E-H, Lee SA, Chung JY, Koh EH, Cho YH, Kim JH, Kim CJ, Kim M-S. Efficacy and safety of cabergoline as first line treatment for invasive giant prolactinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:874–878. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.5.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli E, Giusti M, Miola C, Potenzoni F, Sghedoni D, Camanni F, Giordano G. Effectiveness and tolerability of long term treatment with cabergoline, a new long-lasting ergoline derivative, in hyperprolactinemic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;69:725–728. doi: 10.1210/jcem-69-4-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Di Sarno A, Landi ML, Cirillo S, Sarnacchiaro F, Facciolli G, Pivonello R, Cataldi M, Merola B, Annunziato L, Lombardi G. Long-term and low-dose treatment with cabergoline induces macroprolactinoma shrinkage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3574–3579. doi: 10.1210/jc.82.11.3574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Di Sarno A, Landi ML, Scavuzzo F, Cappabianca P, Pivonello R, Volpe R, Di Salle F, Cirillo S, Annunziato L, Lombardi G. Macroprolactinoma shrinkage during cabergoline treatment is greater in naive patients than in patients pretreated with other dopamine agonists: a prospective study in 110 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2247–2252. doi: 10.1210/jc.85.6.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Vitale G, Di Sarno A, Spiezia S, Guerra E, Ciccarelli A, Lombardi G. Prolactin and prostate hypertrophy: a pilot observational, prospective, case-control study in men with prolactinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2770–2775. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Vitale G, Cappabianca P, Briganti F, Ciccarelli A, De Rosa M, Zarrilli S, Lombardi G. Outcome of cabergoline treatment in men with prolactinoma: effects of a 24-month treatment on prolactin levels, tumor mass, recovery of pituitary function, and semen analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1704–1711. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsello SM, Ubertini G, Altomare M, Lovicu RM, Migneco MG, Rota CA, Colosimo C. Giant prolactinomas in men: Efficacy of cabergoline treatment. Clin Endocrinol. 2003;58:662–670. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis A, Colao A, Savoia A, Coronella C, Pasquali D, Conte M, Pivonello R, Bellastella A, Sinisi AA, Bizzarro A, Lombardi G, Bellastella G. Effect of long-term cabergoline therapy on the immunological pattern and pituitary function of patients with idiopathic hyperprolactinaemia positive for antipituitary antibodies. Clin Endocrinol. 2008;69:285–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa M, Ciccarelli A, Zarrilli S, Guerra E, Gaccione M, Di Sarno A, Lombardi G, Colao A. The treatment with cabergoline for 24 month normalizes the quality of seminal fluid in hyperprolactinaemic males. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;64:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgrange E, Maiter D, Donckier J. Effects of the dopamine agonist cabergoline in patients with prolactinoma intolerant or resistant to bromocriptine. Eur. 1996;134:454–456. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1340454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari C, Paracchi A, Mattei AM, De Vincentiis S, D'Alberton A, Crosignani P. Cabergoline in the long-term therapy of hyperprolactinemic disorders. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1992;126:489–494. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1260489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari CI, Abs R, Bevan JS, Brabant G, Ciccarelli E, Motta T, Mucci M, Muratori M, Musatti L, Verbessem G, Scanlon MF. Treatment of macroprolactinoma with cabergoline: a study of 85 patients. Clin Endocrinol. 1997;46:409–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.1300952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Miki N, Kawamata T, Makino R, Amano K, Seki T, Kubo O, Hori T, Takano K. Prospective study of high-dose cabergoline treatment of prolactinomas in 150 patients.[see comment] J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4721–4727. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Miki N, Amano K, Kawamata T, Seki T, Makino R, Takano K, Izumi S-, Okada Y, Hori T. Individualized high-dose cabergoline therapy for hyperprolactinemic infertility in women with micro- and macroprolactinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2672–2679. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontikides N, Krassas GE, Nikopoulou E, Kaltsas T. Cabergoline as a first-line treatment in newly diagnosed macroprolactinomas. Pituitary. 2000;2:277–281. doi: 10.1023/A:1009913200542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raverot G, Jacob M, Jouanneau E, Delemer B, Vighetto A, Pugeat M, Borson-Chazot F. Secondary deterioration of visual field during cabergoline treatment for macroprolactinoma. Clin Endocrinol. 2009;70:588–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimon I, Benbassat C, Hadani M. Effectiveness of long-term cabergoline treatment for giant prolactinoma: study of 12 men. Eur. 2007;156:225–231. doi: 10.1530/EJE-06-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Sharma BS, Mahapatra AK. Microsurgical management of prolactinomas - clinical and hormonal outcome in a series of 172 cases. Neurol India. 2011;59:532–536. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.84332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walia R, Bhansali A, Dutta P, Khandelwal N, Sialy R, Bhadada S. Recovery pattern of hypothalamo-pituitary-testicular axis in patients with macroprolactinomas after treatment with cabergoline. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:314–319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J, Piscitelli G, Polli A, D'Alberton A, Falsetti L, Ferrari C, Fioretti P, Giordano G, L'Hermite M, Ciccarelli E. et al. The efficacy and tolerability of long-term cabergoline therapy in hyperprolactinaemic disorders: an open, uncontrolled, multicentre study. European Multicentre Cabergoline Study Group. Clin Endocrinol. 1993;39:323–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb02372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, De Rosa M, Sarnacchiaro F, Di Sarno A, Landi ML, Iervolino E, Zarrilli S, Merola B, Lombardi G. Chronic treatment with CV 205-502 restores the gonadal function in hyperprolactinemic males. Eur. 1996;135:548–552. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1350548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranteau L, Chanson P, Lavoinne A, Horlait S, Lubetzki J, Kuhn JM. Effect of the new dopaminergic agonist CV 205-502 on plasma prolactin levels and tumour size in bromocriptine-resistant prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol. 1991;34:25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1991.tb01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvistborg A, Halse J, Bakke S, Bjoro T, Hansen E, Djoseland O, Brownell J, Jervell J. Long-term treatment of macroprolactinomas with CV 205-502. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1993;128:301–307. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1280301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merola B, Sarnacchiaro F, Colao A, Disomma C, Disarno A, Landi ML, Marzullo P, Panza N, Battista C, Lombardi G. CV-205-502 in the treatment of tumoral and nontumoral hyperprolactinemic states. Biomed Pharmacother. 1994;48:167–174. doi: 10.1016/0753-3322(94)90105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morange I, Barlier A, Pellegrini I, Brue T, Enjalbert A, Jaquet P. Prolactinomas resistant to bromocriptine: Long-term efficacy of quinagolide and outcome of pregnancy. Eur. 1996;135:413–420. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1350413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman CB, Hurley AM, Kleinberg DL. Effect of CV 205-502 in hyperprolactinaemic patients intolerant of bromocriptine. Clin Endocrinol. 1989;31:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1989.tb01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickelsen T, Jungmann E, Althoff P, Schummdraeger PM, Usadel KH. Treatment of macroprolactinoma with the new potent nonergot D2-dopamine agonist quinagolide and effects on prolactin levels, pituitary-function, and the renin-aldosterone system- results of a clinical long-term study. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;43:421–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen C, Bergh T, Wide L, Brownell J. Long-term treatment with a new non-ergot long-acting dopamine agonist, CV 205-502, in women with hyperprolactinaemia. Clin Endocrinol. 1988;29:271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1988.tb01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer V, Freneau E, Morange I, Simonetta C. Efficacy of quinagolide in resistance to dopamine agonists: results of a multicenter study. Club de l'Hypophyse. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2000;61:411–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoham Z, Homburg R, Jacobs HS. CV 205–502–effectiveness, tolerability, and safety over 24-month study. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:501–506. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden PF, Lappohn RE, Corbey RS, de Goeij WB, Brownell J, Rolland R. The effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of CV 205-502 in hyperprolactinemic women: a 12-month study. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:574–579. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60966-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Lely AJ, Brownell J, Lamberts SW. The efficacy and tolerability of CV 205-502 (a nonergot dopaminergic drug) in macroprolactinoma patients and in prolactinoma patients intolerant to bromocriptine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72:1136–1141. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-5-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance ML, Lipper M, Klibanski A, Biller BMK, Samaan NA, Molitch ME. Treatment of prolactin-secreting pituitary macroadenomas with the long-acting non-ergot dopamine agonist CV 205-502. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:668–673. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-9-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilar L, Burke CW. Quinagolide efficacy and tolerability in hyperprolactinaemic patients who are resistant to or intolerant of bromocriptine.[see comment] Clin Endocrinol. 1994;41:821–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freda PU, Andreadis CI, Khandji AG, Khoury M, Bruce JN, Jacobs TP, Wardlaw SL. Long-term treatment of prolactin-secreting macroadenomas with pergolide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:8–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.85.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers C, Benker G, Reinwein D. Treatment of prolactinoma patients with the new non-ergot dopamine agonist roxindol: First results. Clin Investig. 1994;72:451–456. doi: 10.1007/BF00180520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrego JJ, Chandler WF, Barkan AL. Pergolide as primary therapy for macroprolactinomas. Pituitary. 2000;3:251–256. doi: 10.1023/A:1012836331506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibal L, Ugwu P, Kendall-Taylor P, Ball SG, James RA, Pearce SH, Hall K, Quinton R. Medical therapy of macroprolactinomas in males: I. Prevalence of hypopituitarism at diagnosis. II. Proportion of cases exhibiting recovery of pituitary function. Pituitary. 2002;5:243–246. doi: 10.1023/A:1025377816769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verde G, Chiodini PG, Liuzzi A, Cozzi R, Favales F, Botalla L, Spelta B, Dalla Bonzana D, Rainer E, Horowski R. Effectiveness of the dopamine agonist lisuride in the treatment of acromegaly and pathological hyperprolactinemic states. J Endocrinol Invest. 1980;3:405–414. doi: 10.1007/BF03349379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezkova J, Hana V, Krsek M, Weiss V, Vladyka V, Liscak R, Vymazal J, Pecen L, Marek J. Use of the Leksell gamma knife in the treatment of prolactinoma patients. Clin Endocrinol. 2009;70:732–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Zhang N, Wang EM, Wang BJ, Dai JZ, Cai PW. Gamma knife radiosurgery as a primary treatment for prolactinomas. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:10–13. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.supplement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouratian N, Sheehan J, Jagannathan J, Laws ER, Steiner L, Vance ML. Gamma knife radiosurgery for medically and surgically refractory prolactinomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:255–266. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000223445.22938.BD. discussion 255-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun DQ, Cheng JJ, Frazier JL, Batra S, Wand G, Kleinberg LR, Rigamonti D, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Salvatori R, Lim M. Treatment of pituitary adenomas using radiosurgery and radiotherapy: a single center experience and review of literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2010;34:181–189. doi: 10.1007/s10143-010-0285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsagarakis S, Grossman A, Plowman PN, Jones AE, Touzel R, Rees LH, Wass JA, Besser GM. Megavoltage pituitary irradiation in the management of prolactinomas: long-term follow-up. Clin Endocrinol. 1991;34:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1991.tb00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SC, Suh TS, Jang HS, Chung SM, Kim YS, Ryu MR, Choi KH, Son HY, Kim MC, Shinn KS. Clinical results of 24 pituitary macroadenomas with linac-based stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:849–853. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Pan L, Dai J, Wang B, Wang E, Zhang W, Cai P. Gamma Knife radiosurgery as a primary surgical treatment for hypersecreting pituitary adenomas. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2000;75:123–128. doi: 10.1159/000048393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zierhut D, Flentje M, Adolph J, Erdmann J, Raue F, Wannenmacher M. External Radiotherapy of Pituitary Adenomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:307–314. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WF, Mashiter K, Doyle FH, Banks LM, Joplin GF. Treatment of prolactin-secreting pituitary tumours in young women by needle implantation of radioactive yttrium. Q J Med. 1978;47:473–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littley MD, Shalet SM, Reid H, Beardwell CG, Sutton ML. The effect of external pituitary irradiation on elevated serum prolactin levels in patients with pituitary macroadenomas. Q J Med. 1991;81:985–998. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/81.3.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudoler SB, Ruffer JE, Gennarelli TA, Savino PJ, Fowble BF. Long-term results of radiotherapy for prolactin-secreting pituitary macroadenomas. Radiat Oncol Investig. 1996;4:185–191. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6823(1996)4:4<185::AID-ROI6>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Link MJ, Brown PD, Stafford SL, Young WF, Pollock BE. Gamma knife radiosurgery for patients with prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas. World Neurosurg. 2010;74:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar AP, Couldwell WT, Chen JCT, Weiss MH. Predictive value of serum prolactin levels measured immediately after transsphenoidal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:307–314. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.2.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babey M, Sahli R, Vajtai I, Andres RH, Seiler RW. Pituitary surgery for small prolactinomas as an alternative to treatment with dopamine agonists. Pituitary. 2011;14:222–230. doi: 10.1007/s11102-010-0283-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarino A, De Marinis L, Anile C, Menini E, Merlini G, Maira G. Dopaminergic mechanisms regulating prolactin secretion in patients with prolactin-secreting pituitary adenoma. Long-term studies after selective transsphenoidal surgery. Metabolism. 1982;31:1100–1104. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier G, de Plunkett T, Jedynak P, Peillon F, Le Gentil P, Racadot J, Visot A, Derome P. Surgical treatment of prolactinomas. Short- and long-term results, prognostic factors. Horm Res. 1985;22:222–227. doi: 10.1159/000180098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusick JR, Fatemi N, Mattozo C, McArthur D, Cohan P, Wang C, Swerdloff RS, Kelly DF. Pituitary function after endonasal surgery for nonadenomatous parasellar tumors: Rathke's cleft cysts, craniopharyngiomas, and meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 2008;70:482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi N, Dusick JR, Mattozo C, McArthur DL, Cohan P, Boscardin J, Wang C, Swerdloff RS, Kelly DF. Pituitary hormonal loss and recovery after transsphenoidal adenoma removal. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:709–718. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000325725.77132.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenbaum SL, Downey DE, Wilson CB, Jaffe RB. Transsphenoidal pituitary resection for preoperative diagnosis of prolactin-secreting pituitary adenoma in women: long term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1711–1719. doi: 10.1210/jc.81.5.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokalp HZ, Deda H, Attar A, Ugur HC, Arasil E, Egemen N. The neurosurgical management of prolactinomas. J Neurosurg Sci. 2000;44:128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti B, Fraioli B, Cantore GP. Results of surgical management of 319 pituitary adenomas. Acta Neurochir. 1987;85:117–124. doi: 10.1007/BF01456107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DK, Vance ML, Boulos PT, Laws ER. Surgical outcomes in hyporesponsive prolactinomas: analysis of patients with resistance or intolerance to dopamine agonists. Pituitary. 2005;8:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s11102-005-5086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirohata T, Uozumi T, Mukada K, Arita K, Kurisu K, Yano T, Takechi A, Onda J. Influence of pregnancy on the serum prolactin level following prolactinoma surgery. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1991;125:259–267. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1250259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws ER, Fode NC, Redmond MJ. Transsphenoidal surgery following unsuccessful prior therapy. An assessment of benefits and risks in 158 patients. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:823–829. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.63.6.0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maira G, Anile C, De Marinis L, Barbarino A. Prolactin-secreting adenomas: Surgical results and long-term follow-up. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:736–743. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198905000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoud F, Serri O, Hardy J, Somma M, Beauregard H. Transsphenoidal adenomectomy for microprolactinomas: 10 to 20 years of follow-up. Surg Neurol. 1996;45:341–346. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(95)00430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H, Iwatsuki K, Yamada M, Hagiwara Y, Moriuchi S, Kadota T. Latent prolactinoma on MRI-selective venous sampling and trans-sphenoidal microsurgical treatment. Neurol Res. 2001;23:691–696. doi: 10.1179/016164101101199199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey P, Ojha BK, Mahapatra AK. Pediatric pituitary adenoma: A series of 42 patients. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Wang M, Wang GD, Han T, Mou CZ, Han LZ, Jiang M, Qu YM, Zhang MA, Pang Q, Xu GM. Surgical outcomes and prognostic factors of transsphenoidal surgery for prolactinoma in men: a single-center experience with 87 consecutive cases. Eur. 2011;164:499–504. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawe SE, Williamson HO, Levine JH, Phansey SA, Hungerford D, Adkins WY. Prolactinomas: surgical therapy, indications and results. Surg Neurol. 1980;14:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh Y, Mori S, Arita N, Nagatani M, Hayakawa T, Koizumi K, Tanizawa O, Uozumi T, Mogami H. Treatment of prolactinoma based on the results of transsphenoidal operations. Surg Neurol. 1986;26:338–344. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(86)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro A, Minniti G, Ruggeri A, Esposito V, Jaffrain-Rea ML, Delfini R. Biochemical remission and recurrence rate of secreting pituitary adenomas after transsphenoidal adenomectomy: long-term endocrinologic follow-up results. Surg Neurol. 2007;68:513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scamoni C, Balzarini C, Crivelli G, Dorizzi A. Treatment and long-term follow-up results of prolactin secreting pituitary adenomas. J Neurosurg Sci. 1991;35:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen CC, Wang YC, Wei-Shan H, Chang CS, Sun MH. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors. Chinese Med J (Taipei) 2000;63:301–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soule SG, Farhi J, Conway GS, Jacobs HS, Powell M. The outcome of hypophysectomy for prolactinomas in the era of dopamine agonist therapy.[see comment] Clin Endocrinol. 1996;44:711–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.738559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J, Page MD, Bevan JS, Richards SH, Douglas-Jones AG, Scanlon MF. Low recurrence rate after partial hypophysectomy for prolactinoma: the predictive value of dynamic prolactin function tests. Clin Endocrinol. 1992;36:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsberger S, Czech T, Vierhapper H, Benavente R, Knosp E. Microprolactinomas in males treated by transsphenoidal surgery. Acta Neurochir. 2003;145:935–940. doi: 10.1007/s00701-003-0134-y. discussion 940-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HW, Sun W, Yang J, Yan CX, Yu CJ. Diagnosis and treatment of pituitary microadenoma: report of 80 cases. Neurol Res. 2008;30:587–593. doi: 10.1179/174313208X310287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamjoom ZAB, Malabarey T, Jamjoom AHB, Sulimani R, Rahman NU, Sadiq S. Problems in the management of large prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas. Saudi Med J. 1995;16:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Saeki N, Nakamura M, Sunami K, Yamaura A. Surgical indication after bromocriptine therapy on giant prolactinomas: Effects and limitations of the medical treatment. Endocr J. 1998;45:529–537. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.45.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CJ, Tam NNC, Joyce JM, Leav I, Ho SM. Gene expression profiling of testosterone and estradiol-17 beta-induced prostatic dysplasia in noble rats and response to the antiestrogen ICI 182,780. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2093–2105. doi: 10.1210/en.143.6.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JA, Davies DL, McLaren EH, Teasdale GM. Ten year follow up of microprolactinoma treated by transsphenoidal surgery. Br Med J. 1994;309:1409–1410. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6966.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oruckaptan HH, Senmevsim O, Ozcan OE, Ozgen T. Pituitary adenomas: results of 684 surgically treated patients and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2000;53:211–219. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(00)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush S, Cooper PR. Symptom resolution, tumor control, and side effects following postoperative radiotherapy for pituitary macroadenomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:1031–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(96)00586-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy SZ, Marziale JC, Rosenbaum AE, Chang JK, Joy SE. The long-term effects of pregnancy and bromocriptine treatment on prolactinomas–the value of radiologic studies. Early Pregnancy. 1997;3:306–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berinder K, Hulting AL, Granath F, Hirschberg AL, Akre O. Parity, pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in women treated for hyperprolactinaemia compared with a control group. Clin Endocrinol. 2007;67:393–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Abs R, Barcena DG, Chanson P, Paulus W, Kleinberg DL. Pregnancy outcomes following cabergoline treatment: extended results from a 12-year observational study. Clin Endocrinol. 2008;68:66–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristiani P, De March A, Bulletti C. Follow-up of 17 hyperprolactinemic pregnant women by plasma prolactin levels and pituitary politomograms. J Gynaecol Endocrinol. 1985;1:48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Crosignani PG, Mattei AM, Scarduelli C, Cavioni V, Boracchi P. Is pregnancy the best treatment for hyperprolactinaemia? Hum Reprod. 1989;4:910–912. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosignani PG, Mattei AM, Severini V, Cavioni V, Maggioni P, Testa G. Long-term effects of time, medical treatment and pregnancy in 176 hyperprolactinemic women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992;44:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(92)90094-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godo G, Koloszar S, Szilagyi I, Daru J, Sas M. Experience relating to pregnancy, lactation, and the afterweaning condition of hyperprolactinemic patients treated with bromocriptine. Fertil Steril. 1989;51:529–531. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren U, Bergstrand G, Hagenfeldt K, Werner S. Women with prolactinoma–effect of pregnancy and lactation on serum prolactin and on tumour growth. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1986;111:452–459. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1110452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcoate WJ, Pound N, Sturrock ND, Lambourne J. Long-term follow-up of patients with hyperprolactinaemia. [see comment] Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996;45:299–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunakaran S, Page RC, Wass JA. The effect of the menopause on prolactin levels in patients with hyperprolactinaemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;54:295–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WF, Doyle FH, Mashiter K, Banks LM, Gordon H, Joplin GF. Pregnancies in women with hyperprolactinaemia: clinical course and obstetric complications of 41 pregnancies in 27 women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1979;86:698–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1979.tb11269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmith MJ, Rosenberg C, Kleinberg D. Visual loss in pregnant women with pituitary adenomas.[see comment] Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:473–477. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-7-199410010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen C, Bergh T, Nillius SJ, Wide L. Return of menstruation and normalization of prolactin in hyperprolactinemic women with bromocriptine-induced pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1985;44:31–34. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48673-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AM, Vilska S, Heinonen PK. Outcome of pregnancies in women with treated or untreated hyperprolactinemia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;63:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse NJ, Niles N, McDonald D, McCorkell S. Prolactin levels in pregnancy: comparison of normal subjects with patients having micro- or macroadenomas after early bromocriptine withdrawal. Horm Res. 1985;21:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000180019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]