Abstract

Objectives. We examined race differences in the longitudinal associations between adolescent alcohol use and adulthood sexually transmitted infection (STI) risk in the United States.

Methods. We estimated multivariable logistic regression models using Waves I (1994–1995: adolescence) and III (2001–2002: young adulthood) of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (n = 10 783) to estimate associations and assess differences between Whites and African Americans.

Results. In adjusted analyses, adolescent alcohol indicators predicted adulthood inconsistent condom use for both races but were significantly stronger, more consistent predictors of elevated partnership levels for African Americans than Whites. Among African Americans but not Whites, self-reported STI was predicted by adolescent report of any prior use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.47; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.00, 2.17) and past-year history of getting drunk (AOR = 1.53; 95% CI = 1.01, 2.32). Among Whites but not African Americans, biologically confirmed STI was predicted by adolescent report of past-year history of getting drunk (AOR = 1.68; 95% CI = 1.07, 2.63) and consistent drinking (AOR = 1.65; 95% CI = 1.03, 2.65).

Conclusions. African American and White adolescent drinkers are priority populations for STI prevention. Prevention of adolescent alcohol use may contribute to reductions in adulthood STI risk.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) disproportionately infect youths aged 15 to 24 years,1 with the highest rates of the most common reportable infections among young adults aged 20 to 24 years.2 Young adult African Americans are disproportionately infected.3 Adolescence, the period preceding young adulthood, is marked by rapid emotional and cognitive growth and exploration of identity.4–7 Risk behaviors that may influence STI often are initiated during this period,8 which is thus critical for implementation of STI prevention interventions.9,10 There is a need to identify the adolescent factors that drive STI risk and to develop adolescent interventions that reduce young adult STI and the race disparity in infection.

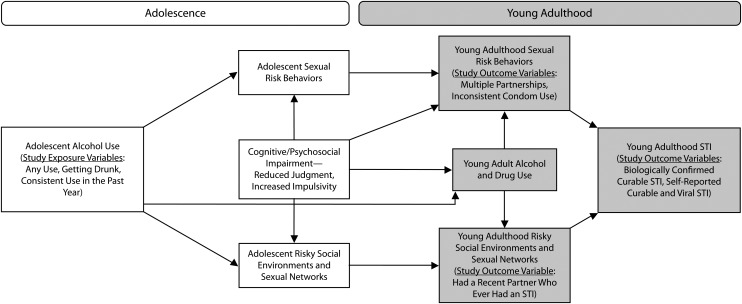

Adolescent alcohol use—the most common adolescent substance use in the United States, reported by more than one third of 8th-grade students and 71% of 12th-grade students11—is associated with sexual risk behaviors12–16 and self-reported STI16,17 among young adults. Adolescent alcohol use is hypothesized to influence STI risk by working through a number of pathways (Figure 1). It is thought to negatively influence cognitive, neurological, and psychosocial development,18–23 which may lead to inhibited judgment and increased impulsivity,24–26 as well as involvement in high-risk behaviors and environments.27,28 Alcohol-related effects on developmental and contextual factors may lead to sexual risk behaviors in adulthood by increasing adolescent sexual risk-taking15,29–31 (which continues into adulthood12,14) or by contributing to long-term cognitive and psychosocial deficits that drive sexual risk-taking during adulthood. In addition, alcohol use may lead to STI risk in adulthood by increasing involvement in high-risk behaviors and social environments, including deviant peer networks, in which risky sexual behavior is normative and risk of sex with an STI-infected partner is elevated.32–36 Finally, adolescent alcohol use may lead to continued alcohol use in young adulthood,37,38 an established risk factor of STI risk in adulthood.31

FIGURE 1—

Hypothesized pathways linking alcohol use in adolescence and risk of sexually transmitted infection in young adulthood.

Current research on alcohol use in adolescence and STI risk in adulthood has been marked by 3 important limitations. First, there is limited understanding of the link between adolescent alcohol use and adulthood STI risk in minority US populations. To our knowledge, no study has assessed race differences in the associations between adolescent alcohol use and adult STI risk, an important limitation given cross-sectional evidence suggesting that in the United States, such associations differ by race. Although there is evidence to suggest that alcohol use is more strongly associated with multiple partnerships among African American than White youths,39 findings also indicate that substance use is associated with STI among White but not African American youths.40

Second, most existing research measuring the longitudinal associations between adolescent alcohol use and STI risk in young adulthood has been conducted in convenience samples, geographically specific populations, or study populations limited by relatively modest sample size.12–15,32 Given the high prevalence of adolescent alcohol use in the United States, along with current evidence of the link between adolescent alcohol use and adult STI risk, there is a need to measure the association using a large, nationally representative sample. Third, to our knowledge, no prior study has examined the association between adolescent alcohol use and biologically confirmed STI, an important limitation given the bias associated with self-reported STI.41

We sought to address these research gaps by using Waves I and III of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) to examine, in a nationally representative sample, race differences (Whites vs African Americans) in the longitudinal associations between multiple dimensions of adolescent alcohol use and adulthood STI risk outcomes. Such outcomes include multiple partnerships, inconsistent condom use, and sex with an STI-infected partner, as well as indicators of infection, including self-reported curable and viral STI and biologically confirmed curable STI. Figure 1 highlights the variables that are explored in the current study.

METHODS

Add Health is a longitudinal cohort study designed to investigate health factors from adolescence into adulthood.42 The study design has been described in detail elsewhere.43–48 During Wave I of the survey (1994–1995), data were collected from adolescents (median age = 16 years; range = 11–21), schools, and parents, and baseline interviews from adolescents provided information on characteristics including sexual behavior and substance use. During Wave III (2001–2002), Wave I participants were reinterviewed as adults and urine specimens were collected for determination of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea by ligase chain reaction (Abbott LCx Probe System; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) and of Trichomonas vaginalis by polymerase chain reaction (Amplicor CT/NG Urine Specimen Prep Kit; Roche Diagnostic Systems, Indianapolis, IN).

Measures

Adolescent alcohol use (Wave I).

Respondents were asked, “Have you had a drink of beer, wine, or liquor—not just a sip or a taste of someone else's drink—more than 2 or 3 times in your life?” Those who answered affirmatively were asked, “During the past 12 months, on how many days did you drink alcohol?” and “On how many days have you gotten drunk or ‘very, very high’ on alcohol?” On the basis of these items, we coded the following 3 dichotomous indicators: lifetime history of alcohol use, history of consistent (more than once per month) drinking in the past year, and history of getting drunk in the past year.

Those who had a lifetime history of alcohol use were asked, “Do you ever drink beer, wine, or liquor when you are not with your parents or other adults in your family?” Those who answered affirmatively were asked, “Think about the first time you had a drink of beer, wine, or liquor when you were not with your parents or other adults in your family. How old were you then?” We assessed age at first alcohol use, a continuous variable indicating the age at which alcohol was first used in adolescence without an adult family member.

Sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted infection (Wave III).

We assessed the following 4 dichotomous indicators of sexual risk in the year preceding Wave III: 2 or more sex partners in the past year; 6 or more partners in the past year; inconsistent condom use in the past year, defined as failure to report use of condoms all of the time during sex in the past year; and sex with an STI-infected partner, defined as a report of sex in the past year with at least 1 partner who, the respondent reported, had ever had an STI. We also examined (1) self-reported curable or viral STI in the past year, defined as self-report that a doctor or nurse had diagnosed them with chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, syphilis, herpes simplex virus 2, or HIV, and (2) biologically confirmed curable STI at Wave III, defined as a positive test result for C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhea, or T. vaginalis on the Wave III urine specimen vs a negative result for all 3 tests.

Covariates.

We considered the following sociodemographic and behavioral factors to be potential confounding variables on the basis of their a priori causal relationship with the exposure and outcome: gender; age (ordinal categorical, with ages 18–20 years and 24–28 years collapsed to ensure an adequate sample size in each age category); age at first vaginal intercourse (ordinal categorical); mother's education measured by Wave I self-report if the mother was interviewed, otherwise by adolescent's report (ordinal categorical); Wave III low functional income status in the past year, defined as the inability of the respondent or respondent's household to pay rent, mortgage, or utilities in the past year (yes vs no); Wave I delinquency, defined as scoring 5 to 7 on a 7-item scale in which delinquency scores ranged from 0 to 7 (yes vs no); and Wave I history of marijuana use (yes vs no).

Data Analysis

For all analyses, we used survey commands in Stata Version 10.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to account for stratification, clustering, and unequal selection probabilities, yielding nationally representative estimates.

We used bivariable analyses to calculate weighted prevalences of participants’ sociodemographic characteristics (at Wave III) and adolescent alcohol use variables (at Wave I) by race, and evaluated whether characteristics differed among Whites vs African Americans. Using logistic regression, we estimated unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between each Wave I indicator of adolescent alcohol use and adulthood sexual risk behavior and STI outcomes. For those who reported 2 or more partners in the past year at Wave III, we conducted analyses of alcohol indicators and adulthood inconsistent condom use. Multivariable models included adjustment for all sociodemographic and behavioral covariates.

For each alcohol use–STI risk association, we tested the significance of a race-by-alcohol-use interaction term (at the P < .05 level) in both an unadjusted and an adjusted model to assess whether the unadjusted and adjusted alcohol use–STI risk association differed significantly among Whites vs African Americans. Because we observed that many alcohol–STI risk associations differed significantly by race, all associations are presented for Whites and African Americans separately. In addition, for each alcohol use–STI risk association, we specified race-specific models and tested the significance of a gender-by-alcohol-use interaction term (at the P < .05 level) in both an unadjusted and an adjusted race-specific model to assess whether the alcohol–STI risk association was significantly different among men vs women within each race category.

For cases in which no gender differences were observed (most models), we specified a model that included a race-by-alcohol-use interaction term to yield the race-specific odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the associations. For cases in which gender differences were observed, we specified a race-specific model and included a gender-by-alcohol-use interaction term to yield race- and gender-specific odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the associations. All models used complete case analysis. We observed minimal missing data (for most study variables, only 0 to 4% of cases were missing data), with the exception of 2 variables. Eighteen percent of all Wave III respondents had missing data for the indicator for biologically confirmed STI; of the Wave III participants, 7.9% refused to provide a urine specimen, 1.6% were unable to provide a urine specimen, 2.9% provided urine specimens that could not be processed because of shipping or laboratory problems, and 6.6% did not have results for all 3 STI tests. In addition, 10% were missing data on mother's education. Although having incomplete data for STI and mother's education was not associated with race/ethnicity, having missing data on these variables was more common among males than females and was associated with increasing age.

RESULTS

The weighted Wave I sample consisted of 18 924 participants, of whom 14 322 (75.7%) were located and reinterviewed during Wave III. A total of 7741 White and 3042 African American respondents with complete sample weight variables were included in the current analyses.

Sociodemographics and Alcohol Use by Race/Ethnicity

Weighted analyses indicated that the analytic sample was 80.9% White and 19.1% African American. The sample was 50.4% male and had a mean age of 21.8 years at Wave III.

At Wave I, Whites were significantly more likely than were African Americans to have ever used alcohol, to have gotten drunk in the past year, and to report consistent alcohol use (Table 1). At Wave I, White and African American adolescents were, on average, 13 years old the first time they ever used alcohol without the presence of an adult family member.

TABLE 1—

Sociodemographic Characteristics, History of Alcohol Use in Adolescence, and Risk of Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) in Adulthood: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Waves I (1994–1995) and III (2001–2002)

| Characteristic | White, No.a (Weighted %b) (n = 7741) | African American, No.a (Weighted %b) (n = 3042) | P (χ2 test) |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 4083 (49.4) | 1716 (50.2) | .634 |

| Male | 3658 (50.6) | 1326 (49.8) | |

| Age, y | |||

| 18–20 | 1926 (29.4) | 756 (25.8) | .443 |

| 21 | 1350 (17.2) | 517 (15.9) | |

| 22 | 1413 (16.4) | 568 (16.4) | |

| 23 | 1439 (15.5) | 556 (16.2) | |

| 24–28 | 1613 (21.6) | 645 (25.7) | |

| Mother's education (Wave I) | |||

| < high school graduate | 673 (10.0) | 410 (19.6) | ≤ .001 |

| High school graduate | 2374 (35.3) | 807 (36.1) | |

| ≥ college | 3905 (54.6) | 1516 (44.3) | |

| Respondent/household could afford housing/utilities in past y (Wave III) | |||

| Yes | 6658 (87.4) | 2440 (79.7) | ≤ .001 |

| No | 994 (12.6) | 560 (20.3) | |

| STI risk in adulthood (Wave III) | |||

| ≥ 2 partners in past y | |||

| No | 5584 (72.8) | 1847 (62.6) | ≤ .001 |

| Yes | 2053 (27.2) | 1108 (37.4) | |

| Had ≥ 6 partners in past y | |||

| No | 7421 (96.7) | 2794 (93.9) | ≤ .001 |

| Yes | 216 (3.3) | 161 (6.1) | |

| Inconsistent condom use in past yc | |||

| No | 1161 (19.6) | 704 (28.8) | ≤ .001 |

| Yes | 4903 (80.4) | 1730 (71.2) | |

| Sex in past y with partner who had ever had an STI | |||

| No | 7139 (95.2) | 2499 (87.4) | ≤ .001 |

| Yes | 367 (4.8) | 351 (12.6) | |

| Biologically confirmed STId | |||

| No | 6112 (96.9) | 2046 (81.5) | < .001 |

| Yes | 201 (3.2) | 435 (18.5) | |

| Self-report of curable or viral STI in past ye | |||

| No | 7399 (96.8) | 2643 (89.1) | < .001 |

| Yes | 240 (3.2) | 300 (10.9) | |

| Alcohol use in adolescence (Wave I) | |||

| Drank any alcohol in past y | |||

| No | 3153 (41.6) | 1572 (52.2) | ≤ .001 |

| Yes | 4548 (58.5) | 1442 (47.8) | |

| Got drunk in past y | |||

| No | 5133 (67.8) | 2498 (81.5) | ≤ .001 |

| Yes | 2541 (32.2) | 504 (18.5) | |

| Consistent drinkingf | |||

| No | 6195 (81.1) | 2622 (85.1) | .045 |

| Yes | 1493 (18.9) | 386 (14.9) | |

Totals may not sum to 7741 White and 3042 African Americans because of missing values.

Use of survey commands to account for stratification, clustering, and unequal selection probabilities yielded nationally representative estimates of White and African American young adults.

Among those who had vaginal sex in past year.

Confirmed to have a positive test result for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, or Trichomonas vaginalis.

Report of being diagnosed with chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, syphilis, herpes simplex virus 2, or HIV in the past year.

Drank more than once per month in past year.

Adolescent Alcohol Use and Adulthood Multiple Partnerships

Whites.

In unadjusted analyses using Whites, adolescent indicators of any prior alcohol use, past-year history of getting drunk, and past-year consistent drinking were each associated with a 40% to 50% increase in the odds of adulthood report of 2 or more sex partners in the past year (Table 2). In adjusted analyses, the associations weakened considerably, and adolescent history of getting drunk remained the only indicator associated with the outcome (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.03, 1.47).

TABLE 2—

Associations Between Adolescent Past-Year Alcohol Use and Adulthood Determinants of Sexually Transmitted Infection Among Young Adults (Aged 18–28 Years): National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Waves I (1994–1995) and III (2001–2002)

| Whites |

African Americans |

||||||

| Variable | % With STI Risk Outcomea | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | % With STI Risk Outcomea | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | P, Unadjusted (Adjusted)c |

| ≥ 2 partners in past year | |||||||

| Any alcohol use in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 22.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 31.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 30.2 | 1.46 (1.25, 1.70) | 1.11 (0.93, 1.33) | 44.1 | 1.74 (1.40, 2.16) | 1.42 (1.09, 1.85) | .188 (.114) |

| Got drunk in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 24.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 34.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 32.9 | 1.52 (1.31, 1.77) | 1.23 (1.03, 1.47) | 51.1 | 2.01 (1.57, 2.60) | 1.55 (1.15, 2.07) | .058 (.163) |

| Consistent drinkingd | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 25.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 34.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 33.2 | 1.43 (1.21, 1.69) | 1.01 (0.83, 1.23) | 51.7 | 2.01 (1.57, 2.56) | 1.88 (1.38, 2.56) | .021 (.001) |

| Age at first alcohol use (continuous)e | NA | 0.95 (0.92, 0.98) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | NA | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) | .480 (.719) |

| Women | 0.90 (0.86, 0.95) | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | |||||

| Men | 0.99 (0.94, 1.04) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.08) | |||||

| ≥ 6 partners in past year | |||||||

| Any alcohol use in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 2.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 3.9 | 1.68 (1.11, 2.55) | 1.14 (0.69, 1.87) | 8.9 | 2.74 (1.64, 4.58) | 2.24 (1.29, 3.88) | .13 (.049) |

| Got drunk in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 2.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 4.4 | 1.68 (1.17, 2.41) | 1.20 (0.73, 1.99) | 13.5 | 3.41 (2.18, 5.34) | 2.53 (1.53, 4.19) | .016 (.018) |

| Consistent drinkingd | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 3.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yese | 4.5 | 1.54 (1.03, 2.30) | 0.94 (0.55, 1.62) | 10.3 | 2.05 (1.25, 3.34) | 1.91 (1.20, 3.03) | |

| Women | NA | 0.72 (0.34, 1.52) | 0.46 (0.19, 1.12) | NA | |||

| Men | NA | 1.87 (1.15, 3.03) | 1.55 (0.79, 3.04) | NA | .380 (.032) | ||

| Age at first alcohol use (continuous) | 0.91 (0.86, 0.96) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.09) | 0.95 (0.87, 1.03) | 1.05 (0.95, 1.15) | .446 (.351) | ||

| Inconsistent condom use among those with ≥2 partners in past year | |||||||

| Any alcohol use in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 74.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 62.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 84.3 | 1.86 (1.43, 2.42) | 1.41 (1.00, 2.01) | 76.2 | 1.93 (1.35, 2.75) | 1.57 (1.04, 2.37) | .865 (.697) |

| Got Drunk in the past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 77.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 67.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 86.7 | 1.94 (1.42, 2.64) | 1.48 (0.97, 2.26) | 77.3 | 1.62 (1.05, 2.51) | 1.36 (0.78, 2.38) | .5 (.789) |

| Consistent drinkingd | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 80.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 67.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 83.7 | 1.28 (0.92, 1.77) | 0.93 (0.60, 1.43) | 80.9 | 2.04 (1.06, 3.93) | 1.63 (0.82, 3.22) | .215 (.163) |

| Age at first alcohol use (continuous) | NA | 1.03 (0.93, 1.13) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.14) | NA | 0.87 (0.74, 1.01) | 0.86 (0.74, 1.01) | .074 (.112) |

| Sex with partner in past year who ever had an STI | |||||||

| Any alcohol use in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 3.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 11.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 5.7 | 1.60 (1.21, 2.12) | 0.97 (0.71, 1.33) | 14.5 | 1.36 (0.96, 1.94) | 1.12 (0.79, 1.59) | .475 (.527) |

| Got drunk in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 4.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 11.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 6.8 | 1.78 (1.32, 2.39) | 1.02 (0.71, 1.45) | 19.5 | 1.94 (1.34, 2.80) | 1.53 (0.98, 2.39) | .724 (.115) |

| Consistent drinkingd | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 5.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 15.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yese | 8.8 | 1.95 (1.46, 2.61) | 1.34 (0.93, 1.93) | 14.0 | 0.97 (0.60, 1.55) | 0.77 (0.46, 1.26) | .013 (.056) |

| Women | 1.51 (1.03, 2.22) | 1.07 (0.69, 1.67) | |||||

| Men | 3.17 (1.98, 5.07) | 2.24 (1.24, 3.91) | |||||

| Age at first alcohol use (continuous) | NA | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) | NA | 0.91 (0.85, 0.98) | 0.91 (0.84, 0.98) | .61 (.07) |

Note.; CI = confidence interval; NA = not applicable; OR = odds ratio; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Use of survey commands to account for stratification, clustering, and unequal selection probabilities yielded nationally representative estimates of White and African American young adults.

Adjusted for gender; age (ordinal categorical: 18–20, 21–22, 23–28 years); age at first sexual intercourse (ordinal categorical: ≥ 15, 16, 17–18, 19–25 years, never); mother's education (ordinal categorical: < high school graduate, high school graduate, or > college graduate); Wave III low functional income status in the past year, defined by the inability of the respondent or his/her household to pay rent/mortgage payment or utilities in the past year (yes vs no); Wave I delinquency, defined by scoring a 5, 6, or 7 on a 7-item scale in which delinquency scores ranged from 0 to 7 (yes vs no); and Wave I history of marijuana use (yes vs no).

P value for race difference in unadjusted associations and (in parentheses) adjusted associations.

More than once per month in the past year.

Because the race-specific unadjusted associations differed significantly by gender at the .05 level, estimates are presented separately for men and women.

In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, increasing age at first alcohol use was associated with lower levels of adulthood history of 2 or more partnerships in the past year among women (AOR = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.89, 1.01) but not men.

Adolescent report of any prior use, past-year history of getting drunk, and past-year history of consistent use were each associated with a 50% to 70% increase in the odds of having 6 or more partners in the past year. In adjusted analyses, the associations weakened and were no longer significant.

In unadjusted analyses, age at first alcohol use was weakly associated with adulthood history of 6 or more partnerships in the past year; after adjustment for confounders, however, there was no association.

African Americans.

In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses using African Americans, adulthood history of 2 or more partnerships in the past year was predicted by adolescent report of any prior use (AOR = 1.42; 95% CI = 1.09, 1.85), past-year history of getting drunk (AOR = 1.55; 95% CI = 1.15, 2.07), and past-year consistent drinking (AOR = 1.88; 95% CI = 1.38, 2.56) (Table 2). These adjusted associations between consistent drinking in adolescence and adulthood report of 2 or more partners were significantly stronger among African Americans than among Whites (P = .001 for interaction term).

In unadjusted analyses, age at first alcohol use was weakly associated with 2 or more partnerships in the past year, but there was no association after adjustment for confounders.

In unadjusted and adjusted analyses, any adolescent alcohol use (AOR = 2.24; 95% CI = 1.29, 3.88), past-year history of getting drunk (AOR = 2.53; 95% CI = 1.53, 4.19), and past-year consistent drinking (AOR = 1.91; 95% CI = 1.20, 3.03) were associated with adult report of 6 or more partners in the past year (Table 2). Adjusted models indicated that these adolescent alcohol indicators were significantly stronger predictors of adulthood recent history of 6 or more partners among African Americans than among Whites (P < .05 for each interaction term). Age at first alcohol use was not associated with adulthood recent history of 6 or more partners.

Adolescent Alcohol Use and Adulthood Inconsistent Condom Use

Whites.

Among White adults reporting 2 or more partnerships in the past year, adolescent history of any alcohol use and past-year history of getting drunk were each associated with a 90% increase in the odds of inconsistent condom use in adulthood (Table 2). In adjusted analyses, these associations weakened but appeared to remain (for any prior alcohol use, AOR = 1.41; 95% CI = 1.00, 2.01; for past-year history of getting drunk, AOR = 1.48; 95% CI = 0.97, 2.26). Adolescent report of past-year consistent alcohol use was not associated with inconsistent condom use in adulthood. Age at first alcohol use was not associated with inconsistent condom use among Whites.

African Americans.

In unadjusted analyses using African Americans, each adolescent alcohol use indicator was associated with an increase of at least 60% in the odds of inconsistent condom use in adulthood (Table 2). In adjusted analyses, the association between any adolescent alcohol use and condom use inconsistency remained (AOR = 1.57; 95% CI = 1.04, 2.37), but adolescent histories of getting drunk and drinking consistently were no longer significantly associated with inconsistent condom use in adulthood. Age at first alcohol use was not associated with the outcome.

Adolescent Alcohol Use and Adulthood Sex With Infected Partner

Whites.

Any prior alcohol use, getting drunk, and consistent drinking in the past year were associated with a 60% to 95% increase in the odds of the outcome among Whites (Table 2). In adjusted analyses in which men and women were combined, these adolescent alcohol use indicators were no longer associated with adulthood sex with an infected partner. However, adolescent report of past-year consistent alcohol use predicted the outcome among White men (AOR = 2.24; 95% CI = 1.28, 3.91) but not among White women. Age at first alcohol use was not associated with adulthood history of sex with an STI-infected partner.

African Americans.

Adolescent indicators of any prior alcohol use and past-year consistent alcohol use were not associated with adulthood sex with an infected partner among African Americans (Table 2). In unadjusted analyses, a strong to moderate association was observed between adolescent report of getting drunk in the past year and adulthood sex with an infected partner (OR = 1.94; 95% CI = 1.34, 2.80). The association appeared to remain in adjusted models (AOR = 1.53; 95% CI = 0.98, 2.39), although the result was not significant at the .05 level. In both unadjusted and adjusted models, older age at first alcohol use predicted significant reductions in odds of sex with an infected partner in adulthood (AOR = 0.91; 95% CI = 0.84, 0.98).

Adolescent Alcohol Use and Adulthood STI

Whites.

Among Whites, adolescent reports of any alcohol use and of past-year history of getting drunk were associated with a 60% to 70% increase in the odds of self-reported STI, although these associations weakened and were no longer significant when confounders were controlled for (Table 3). Adolescent report of consistent use was not associated with self-reported STI. Age of first alcohol use was not associated with self-reported STI.

TABLE 3—

Associations Between Adolescent Past-Year Alcohol Use and Adulthood Sexually Transmitted Infection Among Young Adults (Aged 18–28 Years): National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Waves I (1994–1995) and III (2001–2002)

| Whites |

African Americans |

||||||

| % With STI Risk Outcomea | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | % With STI Risk Outcomea | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | P, Unadjusted (Adjusted)c | |

| Self-reported curable or viral STI in past year | |||||||

| Any alcohol use in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 2.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 8.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 3.8 | 1.73 (1.23, 2.45) | 1.30 (0.85, 2.00) | 14.0 | 1.82 (1.31, 2.52) | 1.47 (1.00, 2.17) | .833 (.61) |

| Got drunk in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 2.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 4.2 | 1.59 (1.16, 2.17) | 1.13 (0.75, 1.69) | 16.8 | 1.88 (1.25, 2.81) | 1.53 (1.01, 2.32) | .538 (.268) |

| Consistent drinkingd | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 3.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 10.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 3.6 | 1.16 (0.82, 1.66) | 0.89 (0.60, 1.34) | 13.8 | 1.36 (0.84, 2.21) | 1.07 (0.63, 1.84) | .628 (.58) |

| Age at first alcohol use (continuous) | NA | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.17) | NA | 0.91 (0.85, 0.99) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) | .05 (.071) |

| Biologically confirmed curable STI at Wave III | |||||||

| Any alcohol use in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 2.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 20.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 3.7 | 1.53 (1.02, 2.30) | 1.20 (0.75, 1.93) | 16.9 | 0.80 (0.61, 1.06) | 0.64 (0.45, 0.92) | .011 (.027) |

| Got drunk in past y | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 2.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 18.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yese | 4.5 | 1.80 (1.20, 2.70) | 1.68 (1.07, 2.63) | 17.9 | 0.94 (0.69, 1.28) | 0.89 (0.59, 1.35) | |

| Women | 0.71 (0.46, 1.09) | 0.57 (0.31, 1.04) | |||||

| Men | 1.43 (0.88, 2.33) | 1.29 (0.68, 2.45) | .015 (.027) | ||||

| Consistent drinkingd | |||||||

| No (Ref) | 2.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 19.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 4.6 | 1.67 (1.12, 2.48) | 1.65 (1.03, 2.65) | 16.1 | 0.82 (0.51, 1.31) | 0.88 (0.54, 1.44) | .023 (.055) |

| Age at first alcohol use (continuous) | NA | 0.94 (0.85, 1.03) | 0.95 (0.85, 1.06) | NA | 1.03 (0.94, 1.13) | 1.04 (0.93, 1.16) | .161 (.268) |

Note. STI = sexually transmitted infection; OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; NA = not applicable.

Use of survey commands to account for stratification, clustering, and unequal selection probabilities yielded nationally representative estimates of White and African American young adults.

Adjusted for gender, age (ordinal categorical: 18–20, 21–22, 23–28 years); age at first sexual intercourse (ordinal categorical: ≤ 15, 16, 17–18, 19–25 years, never); mother's education (ordinal categorical: less than high school graduate, high school graduate, or more than college graduate); Wave III low functional income status in the past year, defined as the inability of the respondent or his/her household to pay rent/mortgage payment or utilities in the past year (yes vs no); Wave I delinquency, defined as scoring 5, 6, or 7 on a 7-item scale in which delinquency scores ranged from 0 to 7 (yes vs no); and Wave I history of marijuana use (yes vs no).

P value for race difference in unadjusted associations and (in parentheses) adjusted associations.

More than once per month in the past year.

Because the race-specific unadjusted associations differed significantly by gender at the .05 level, estimates are presented separately for men and women.

Adolescent indicators of any prior use, past-year history of getting drunk, and consistent drinking were each associated with a 50% to 80% increase in the odds of biologically confirmed curable STI. In adjusted analyses, biologically confirmed STI was predicted by adolescent report of past-year history of getting drunk (AOR = 1.68; 95% CI = 1.07, 2.63) and consistent drinking (AOR = 1.65; 95% CI = 1.03, 2.65), but not by any prior alcohol use. Age at first alcohol use was not associated with biologically confirmed STI.

African Americans.

In both unadjusted and adjusted models, adolescent reports of any prior alcohol use and of getting drunk in the previous year were associated with adulthood self-reported STI (for any alcohol, AOR = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.00, 2.17; for getting drunk, AOR = 1.53; 95% CI = 1.01, 2.32). Consistent adolescent drinking was not associated with self-reported STI in young adulthood. Age at first alcohol use was associated with lower levels of self-reported STI, although this association was attenuated in adjusted analyses.

In adjusted analyses, any prior alcohol use was inversely associated with adulthood biologically confirmed STI (AOR = 0.64; 95% CI = 0.45, 0.92), whereas adolescent past-year history of getting drunk and consistent use were not associated. The adjusted associations between any prior use in adolescence and adult biologically confirmed STI, as well as past-year history of getting drunk in adolescence and adult biologically confirmed STI, differed significantly by race (P < .05 for each race interaction term). Age of first alcohol use was not associated with biologically confirmed STI.

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative sample of White and African American adults aged 18 to 28 years, adolescent report of any prior use, getting drunk, or consistent use of alcohol predicted elevated odds of either adult biologically confirmed or self-reported STI and STI determinants, including multiple partnerships, inconsistent condom use, and in some cases, sex with an STI-infected partner (Figure 1). Adjusted analyses suggested that associations between adolescent alcohol use and adult STI risk remained independent of important confounders, including sociodemographic factors, delinquency, and use of marijuana. The results support prior evidence of the link between adolescent alcohol use and later adolescent or adult STI risk12–17 and indicate that, in the general US population, adolescent alcohol use is an important marker of a high-risk trajectory that results in sexual risk and infection in adulthood. The findings also provide further evidence to suggest that adolescent alcohol use may contribute to STI risk in adulthood among Whites and African Americans.

This study is the first to our knowledge to evaluate race differences in the associations between adolescent alcohol use and adult STI risk. Adolescent alcohol indicators more strongly and consistently predicted high partnership levels among African Americans than among Whites. Among African Americans, and not among Whites, even the indicator of lifetime history of any prior alcohol use was associated with a 40% increase in the odds of 2 or more partners and with twice the odds of 6 or more partners in the past year in adulthood. These findings support previous cross-sectional research demonstrating higher odds of multiple partnerships among African American adolescent alcohol users than among their White counterparts.39

In addition, adolescent report of any prior use, past-year history of getting drunk, and past-year consistent drinking predicted increases in self-reported curable and viral infections in adulthood among African Americans, but not Whites, further suggesting that adolescent alcohol use may have particularly deleterious effects on the long-term STI risk of African Americans. This finding is consistent with evidence demonstrating that adolescent and young adulthood alcohol consumption is associated with greater levels of negative outcomes in later adolescence and adulthood among African Americans than among Whites.49,50 Results may also indicate that there are unique clusters of problem behaviors in different racial and ethnic groups. Previous research found that African Americans are more likely to exhibit clusters of risks or problem behaviors, whereas Whites are more likely to display a balance of risky and protective or healthy behaviors.51

By contrast, however, indicators of adolescent history of getting drunk and consistent drinking were positively associated with biologically confirmed curable STI in adulthood among Whites, but not African Americans. High levels of biologically confirmed STI were observed not only among African Americans who had used alcohol in adolescence, but also among those who had no history of adolescent alcohol use. In fact, any prior alcohol use appeared to be inversely associated with biologically confirmed infection; 20% of African Americans who reported no prior use of alcohol in adolescence tested positive for an STI at Wave III vs 16% of those who reported any adolescent alcohol use.

There is no clear explanation for why nonusers of alcohol may have comparable or even greater risk of STI compared with nonusers. It is believed, however, that high levels of STI among low-risk African Americans result from the dense, highly segregated sexual networks of African Americans. This leads to high levels of sexual mixing between high-risk and low-risk African American populations and a disproportionate concentration of infection, even among those who do not engage in behaviors such as substance use that may increase STI risk.40,52 The results of the current study support a previous Add Health study that found minimal association between adult substance use and adult STI among African Americans; high levels of STI were measured in all African American populations, including those who did not report substance use.40

The current study's finding of null associations between adolescent alcohol use and biologically confirmed STI among African Americans contradict our observation that adolescent alcohol use was associated with elevations in self-reported current infection in this group. It is possible that adolescent alcohol use is strongly associated with the indicator of self-reported STI yet weakly associated with the STI biomarker because of differences in the STIs assessed by the 2 measures; Add Health did not test for common infections, including herpes, that were assessed with the self-reported STI indicator. However, it also is possible that the observed association between adolescent alcohol use and self-reported STI among African Americans was biased because of inaccuracy of self-reported STI.41 Furthermore, STI reporting bias may have been associated with adolescent alcohol use, creating inflated associations between adolescent alcohol use and self-reported STI among African Americans. Specifically, African American respondents who had used alcohol during adolescence and who had elevated levels of sex partnership in adulthood may have had elevated perceived risk of infection, increased levels of STI testing and care, and hence improved detection of infection. Likewise, African Americans who had not used alcohol in adolescence and who reported lower partnership levels may have had lower perceived risk, been less likely to seek care, and hence were differentially affected by underdiagnosed current STI.

In sum, it is possible that whereas adolescent alcohol use may lead to risk behaviors in young adulthood among African Americans, elevations in risk behaviors may not translate to true increases in infection risk. These findings suggest that although prevention of alcohol use among African American adolescents may lead to later reductions in numbers of sex partners—an important component in the prevention of STI, including HIV—these resulting reductions in partnership levels may not be sufficient to reduce the burden of infection. Hence, adolescent alcohol prevention should also be paired with rigorous, consistent STI testing and treatment and condom promotion among all youths. In addition, to reduce race disparities in STI, upstream interventions are needed to reduce the segregation, poverty, and discrimination that contribute to the disproportionate concentration of infection levels in African American communities.

A number of limitations should be considered in interpreting the results of this study. First, alcohol consumption and sexual behavior are likely to co-occur53–56 because of sociodemographic characteristics or underlying personality factors, such as impulsivity and sensation seeking,55,57 that may fuel both adolescent alcohol use and STI risk in adulthood. Hence, although we attempted to control for key confounders, including delinquency in adolescence, that may drive adolescent alcohol use and subsequent risk-taking, residual confounding is an important concern. In addition, because of a lack of biomarker data on viral STI and on partner's infection status in Add Health, we also examined self-reported curable and viral STI and self-reported history of sex with an STI-infected partner; however, self-reported STI is a biased estimate of infection.41 Finally, although we observed low levels of missing data for most variables, appreciable levels of missing data were observed for biologically confirmed infection and 1 covariate, mother's education. Furthermore, missing data on biologically confirmed STI and maternal education—the variables with the greatest levels of missing data—were associated with male gender and older age. The resulting differential in missing data may have led to biased estimations of associations between alcohol use and STI risk.

This study has expanded previous research to provide evidence in a nationally representative sample that alcohol use in adolescence is linked to disproportionate STI risk in adulthood among both Whites and African Americans. The results highlight a need for improved integration of alcohol and STI prevention and treatment for adolescents in the general population. Parents, schools, and health care providers should improve communication about alcohol use in attempts to delay use and should identify alcohol users to address use and potentially prevent adverse health effects.58 Promising interventions include alcohol expectancy challenges, motivational interviewing techniques, and addressing the underlying personality and motivational factors predicting alcohol consumption.59 Preventing alcohol use and STI risk will involve a multisystems approach in which prevention efforts are integrated and delivery methods are innovative and developmentally appropriate.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institute on Drug Abuse grant entitled “Longitudinal Study of Substance Use, Incarceration, and STI in the US” (R03 DA026735; Maria Khan, principal investigator). The study uses data from Add Health, a project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant P01- HD31921), with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies.

Special acknowledgment is due to Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design.

Human Participant Protection

Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the University of Maryland at College Park institutional review board.

References

- 1.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):6–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention STD health equity. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/health-disparities/default.htm. Accessed November 4, 2011

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV surveillance report, 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report/pdf/2009SurveillanceReport.pdf. Accessed November 4 2011

- 4.Hall G. Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relation to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1904 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erikson E. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York, NY: Norton; 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcia J. Development and validation of ego-identity status. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1966;3(6):551–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piaget J. The Psychology of Intelligence. London, UK: Routledge and Kegan Paul; 1950 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donovan JE, Jessor R. Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53(6):890–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002;(14):54–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherrod LR, Haggerty RJ, Featherman DL. Introduction: late adolescence and the transition to adulthood. J Res Adolesc. 1993;3(3):217–226 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2010. Volume I: Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo J, Chung IJ, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Developmental relationships between adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(4):354–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staton M, Leukefeld C, Logan TKet al. Risky sex behavior and substance use among young adults. Health Soc Work. 1999;24(2):147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strachman A, Impett EA, Henson JM, Pentz MA. Early adolescent alcohol use and sexual experience by emerging adulthood: a 10-year longitudinal investigation. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(5):478–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tapert SF, Aarons GA, Sedlar GR, Brown SA. Adolescent substance use and sexual risk-taking behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(3):181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells JE, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM. Drinking patterns in mid-adolescence and psychosocial outcomes in late adolescence and early adulthood. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1529–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Alcohol and STI risk: evidence from a New Zealand longitudinal birth cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113(2–3):200–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field M, Schoenmakers T, Wiers RW. Cognitive processes in alcohol binges: a review and research agenda. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1(3):263–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corte CM, Sommers MS. Alcohol and risky behaviors. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2005;23:327–360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartley DE, Elsabagh S, File SE. Binge drinking and sex: effects on mood and cognitive function in healthy young volunteers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78(3):611–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Tapert SF. The influence of substance use on adolescent brain development. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2009;40(1):31–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Townshend JM, Duka T. Binge drinking, cognitive performance and mood in a population of young social drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(3):317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown SA, Tapert SF, Granholm E, Delis DC. Neurocognitive functioning of adolescents: effects of protracted alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(2):164–171 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict Biol. 2009;14(1):22–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norris J, Stoner SA, Hessler DMet al. Cognitive mediation of alcohol's effects on women's in-the-moment sexual decision making. Health Psychol. 2009;28(1):20–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fromme K, D'Amico EJ, Katz EC. Intoxicated sexual risk taking: an expectancy or cognitive impairment explanation? J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60(1):54–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007;199(1):76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maney DW, Higham-Gardill DA, Mahoney BS. The alcohol-related psychosocial and behavioral risks of a nationally representative sample of adolescents. J Sch Health. 2002;72(4):157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards JM, Iritani BJ, Hallfors DD. Prevalence and correlates of exchanging sex for drugs or money among adolescents in the United States. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(5):354–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stueve A, O'Donnell LN. Early alcohol initiation and subsequent sexual and alcohol risk behaviors among urban youths. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(5):887–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(3):156–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M, Clark S, Owen LD. Heterosexual risk behaviors in at-risk young men from early adolescence to young adulthood: prevalence, prediction, and association with STD contraction. Dev Psychol. 2002;38(3):394–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Spirito A. Adolescents’ and their friends’ health-risk behavior: factors that alter or add to peer influence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(5):287–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. Effects of parental monitoring and peer deviance on substance use and delinquency. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68(4):1084–1104 [Google Scholar]

- 35.D'Amico EJ, Edelen MO, Miles JNV, Morral AR. The longitudinal association between substance use and delinquency among high-risk youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93(1–2):85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Komro KA, Tobler AL, Maldonado-Molina MM, Perry CL. Effects of alcohol use initiation patterns on high-risk behaviors among urban, low-income, young adolescents. Prev Sci. 2010;11(1):14–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MTet al. Adolescent alcohol use is a risk factor for adult alcohol and drug dependence: evidence from a twin design. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Englund MM, Egeland B, Oliva EM, Collins WA. Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: a longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction. 2008;103(suppl 1):23–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valois RF, Oeltmann JE, Waller J, Hussey JR. Relationship between number of sexual intercourse partners and selected health risk behaviors among public high school adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(5):328–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: the need for new directions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iritani BJ, Ford CA, Miller WC, Hallfors DD, Halpern CT. Comparison of self-reported and test-identified chlamydial infections among young adults in the United States of America. Sex Health. 2006;3(4):245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Web site. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth. Accessed November 4, 2011

- 43.Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: study design. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design. Accessed November 4, 2011

- 44.Udry JR. References, instruments, and questionnaires consulted in the development of the Add Health In-Home Adolescent Interview. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/refer.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RWet al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chantala K, Tabor J. Strategies to perform a design-based analysis using the Add Health data. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/weight1.pdf. Revised 2010. Accessed November 4, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sieving RE, Beuhring T, Resnick MDet al. Development of adolescent self-report measures from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(1):73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Add Health Biomarkers Team Biomarkers in Wave III of the Add Health Study. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/biomark.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sloan FA, Costanzo PR, Belsky Det al. Heavy drinking in early adulthood and outcomes at mid life. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(7):600–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horton EG. Racial differences in the effects of age of onset on alcohol consumption and development of alcohol-related problems among males from mid-adolescence to young adulthood. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2007;6(1):1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weden MM, Zabin LS. Gender and ethnic differences in the co-occurrence of adolescent risk behaviors. Ethn Health. 2005;10(3):213–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(5):250–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baskin-Sommers A, Sommers I. The co-occurrence of substance use and high-risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(5):609–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willoughby T, Chalmers H, Busseri MA. Where is the syndrome? Examining co-occurrence among multiple problem behaviors in adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1022–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brookmeyer KA, Henrich CC. Disentangling adolescent pathways of sexual risk taking. J Prim Prev. 2009;30(6):677–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hittner JB, Swickert R. Sensation seeking and alcohol use: a meta-analytic review. Addict Behav. 2006;31(8):1383–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hallfors D, Van Dorn RA. Strengthening the role of two key institutions in the prevention of adolescent substance abuse. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(1):17–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stewart SH, Conrod PJ, Marlatt GA, Comeau MN, Thush C, Krank M. New developments in prevention and early intervention for alcohol abuse in youths. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(2):278–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]