Abstract

Several aspects of social psychological science shed light on how unexamined racial/ethnic biases contribute to health care disparities.

Biases are complex but systematic, differing by racial/ethnic group and not limited to love–hate polarities. Group images on the universal social cognitive dimensions of competence and warmth determine the content of each group's overall stereotype, distinct emotional prejudices (pity, envy, disgust, pride), and discriminatory tendencies. These biases are often unconscious and occur despite the best intentions.

Such ambivalent and automatic biases can influence medical decisions and interactions, systematically producing discrimination in health care and ultimately disparities in health. Understanding how these processes may contribute to bias in health care can help guide interventions to address racial and ethnic disparities in health.

IN THE UNITED STATES, BLACKS, Latinos, and American Indians report and have more health problems than do Whites.1 Minorities also suffer much higher mortality rates than do Whites for many conditions. The mortality rate is 50% higher for Blacks than for Whites for strokes, prostate cancer, and cervical cancer.2 Moreover, the gap in mortality rates between Blacks and Whites for several illnesses (heart disease, female breast cancer, and diabetes) has significantly widened in recent years.3

Explanations for group health disparities often focus on structural factors, such as differences in socioeconomic status and access to health care.4 Although these and other factors contribute to health disparities, bias among health care providers also exerts an independent influence.4,5 In addition, patients' responses to bias (e.g., mistrust6) or patients’ own biases may inhibit them from seeking medical care or reduce adherence to physicians’ recommendations.7 Biases can operate in unexamined but systematic ways—even among people committed by professional and personal values to helping others—to adversely affect medical decision-making, clinical interactions, and the responsiveness of patients.

Recent theoretical developments concerning the complex and subtle nature of racial and ethnic bias offer insights into current disparities in health care.8–10 Overall, racial/ethnic minorities receive poorer quality health care than do Whites in the United States,5 but disparities in health care are manifested in various ways. For example, Black patients are less likely than White patients to be recommended for surgery for oral cancers,11 and Latinas and Chinese women are less likely than are White women to receive adjuvant hormonal therapy, which decreases the risk for recurrence of breast cancer.12 Racial and ethnic minority patients are also more likely than are White patients to be recommended for and to undergo unnecessary surgeries.13,14 In addition, for some conditions (e.g., prostate cancer for Asians and coronary heart disease for Latinos) minorities fare better than Whites.2

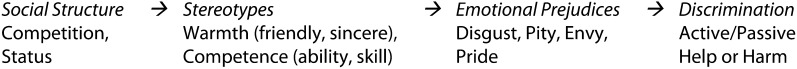

Psychologists have traditionally focused on processes common to bias toward various groups, but emerging trends emphasize important distinctions. In particular, the content of stereotypes differs systematically across groups, and consequently people's emotional prejudices and behavioral responses vary across social groups.15 Moreover, prejudice and stereotypes do not have to be consciously endorsed to produce discrimination; people often respond automatically—frequently without awareness—to others' race or ethnicity, activating stereotypical beliefs, emotional prejudices, and discriminatory tendencies (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Stereotype Content Model links among key variables potentially giving rise to disparate treatment.

Note. Arrows indicate primary causal direction shown among variables in each column. The competition, warmth, active discrimination row is mediated by high-warmth (pride, pity) vs low-warmth (disgust, envy) emotions. The status, competence, passive discrimination row is mediated by high-competence (pride, envy) vs low-competence (disgust, pity) emotions.

These developments in social psychology have implications for understanding health care disparities and combating bias in health care. Two fundamental dimensions of social perception—perceived warmth and competence of groups—shape the content of stereotypes, emotional reactions to groups, and ultimately the amount and type of discrimination expressed. The distinct psychological processes of implicit and explicit bias translate in specific ways into behavior generally and into the context of health care. The expectations and experiences of patients also influence the effectiveness of medical encounters.

THE MULTIDIMEMSIONAL NATURE OF BIAS

Biases come in distinct types that camouflage their detection and their effects. Biases are not uniformly negative or positive, but often mixed and ambivalent.

Whenever anyone first encounters another person, 2 adaptive questions arise. First, does this person intend to cooperate or not? If the other is cooperative, then the person seems warm; if resistant, then the other is cold. Second, the perceiver needs to decide whether the other can enact those good or ill intentions. If the other is high status, people infer competence; otherwise they do not. Extensive evidence shows that these 2 dimensions—generally representing warmth and competence—centrally determine how people respond to individuals16–19 and groups.20–24

The dimensions of perceived warmth and competence are continuous. How people respond to individuals and groups thus reflects gradations along both dimensions.25,26 The Stereotype Content Model (SCM) maps groups that initial respondents report most spontaneously.20–22,25,26 Later respondent ratings then situate the groups on the warmth and competence dimensions. Table 1 represents a simplified 2 × 2 cognitive space, identifying groups that consistently fall into different quadrants. For illustration, we list representative groups within each quadrant, but we note that empirically, groups vary continuously along the 2 dimensions even within each quadrant,20,25 and thus stereotypical reactions may be similar but not entirely identical. Additional dimensions also acknowledge considerable variability in reactions to individual members within a group. For example, Blacks who are darker skinned or who have more typically African facial features experience greater bias,30 as do Asians and Latinos with stronger accents.31

TABLE 1—

Stereotype Content Model Quadrants Illustrating Implicit Biases and Discrimination Arising From Group Stereotypes

| Stereotype Contents | Low Competence/Status | High Competence/Status | Type of Discrimination |

| High warmth/cooperation | Irish immigrants, Italian immigrants, older people, disabled people, effeminate gay men, housewives (pity, sympathy) | Middle-class Whites, Christians, heterosexuals, Canadian immigrants, third-generation immigrants, closeted gay men (pride, admiration) | Active help/protect |

| Low warmth/cooperation | Poor Blacks, undocumented immigrants, Latinos, poor Whites, homeless people, drug addicts, rough-trade gay men (disgust, contempt) | Black professionals, Asian immigrants, Jewish Americans, outsider entrepreneurs, lesbians, professional women, gay male professionals (envy, jealousy) | Active harm/attack |

| Type of discrimination | Passive harm/neglect | Passive help/association |

Note. Row (warmth) and column (competence) headers indicate the stereotype content reported for societal groups listed. Perceived cooperation predicts warmth, and perceived status predicts competence. Placement of groups derived from cluster analyses of surveys of how adults view groups in society. Emotions in parentheses are most commonly reported as directed toward those groups. Behavioral tendencies directed toward each quadrant appear at the end of each row and column, creating mixed behavior in the bottom right and top left quadrants.

SCM's mental mapping affects even people who do not individually endorse these beliefs, because it represents where different groups stand in the larger cultural context. Thus, both health care providers and patients are potentially influenced by these stereotypes.32 Although they are trained to be rational rather than emotional, health care providers, particularly when they are under time pressure and have other demands on their cognitive resources, are likely subject to the same biases that exist among the general population,26,33 despite their devotion to helping others.

Stereotypes, Emotional Prejudices, Discrimination

Representative surveys, responses from convenience samples, laboratory experiments, neuroimaging data, and cross-cultural comparisons reveal basic principles of intergroup reactions as a function of perceived warmth and competence for distinct social groups.21–23,34,35 Of course, individuals have multiple identities and may belong to various combinations of these groups. Indeed, many of the groups represented in Table 1 possess subgroup or intersectional identities (e.g., poor Blacks and professional Blacks). When people have multiple social identities or encounter others who can be classified in multiple ways, they respond to the category (broad or intersectional) that is most salient in those circumstances.36,37 Understanding how groups are perceived in terms of warmth and competence can illuminate a broad range of reactions.

Stereotypically low-warmth, low-competence out-groups.

In SCM studies,25,26 poor Blacks, undocumented immigrants, Latinos, and poor Whites are seen as low in both warmth and competence22,27-29 Groups perceived as low warmth, low competence elicit more contempt and disgust than do other groups. These are particularly dehumanizing emotions, and neuroimaging data on responses to other groups in this quadrant (homeless people and drug addicts) fit the pattern of disgusted, dehumanizing responses.28,38

Emotions, in turn, predict behavior.15,33,39 The negative emotions of disgust and contempt predict a vicious combination of discriminatory behavior: both passive harm (neglect, demean) and active harm (attack, fight).26 Clearly, most people do not actually attack people stereotyped as low warmth, low competence, but passive disregard is reflected in participants’ reports of actively avoiding such persons.26 All these groups become, at a minimum, invisible and at worst, harmed with impunity.40

In health care research, indicators of contemptuous prejudices could appear in inferior treatment, passive neglect, and even unnecessarily active-aggressive last-ditch treatments (e.g., limb amputations in patients with diabetes). Health-related policies have been proposed that exclude undocumented immigrants from receiving support for basic inoculations against prevalent childhood diseases.41 Neglect of pain medication might also indicate passive harm.42 These are empirical questions to investigate.

Stereotypically high-warmth, low-competence out-groups.

In SCM research,25,26 Irish and Italian immigrants, older people, and people with either mental or physical disabilities are stereotyped as high on warmth but low on competence. These groups are viewed as low status but well meaning in their own ineffectual way. People report pity and sympathy toward these groups. These reactions are not completely benign, however. Paternalistic emotions, such as pity, feel subjectively benign but disrespect their target. Pity elicits both passive neglect and social isolation, simultaneously with active caregiving and help.26 This paradoxical combination may appear in institutionalized settings, such as extended care units within hospitals or some nursing homes, where inhabitants may receive complete health care but remain socially isolated.43

Stereotypically high-competence, low-warmth out-groups.

In SCM research,25,26 another ambivalent combination is groups seen as competent but cold: Black professionals, Asian immigrants, Jewish Americans, professional women, lesbians, and gay professionals.21 These groups are acknowledged to be high status and successful, but they are viewed as potentially exploitative and untrustworthy. They elicit envy and jealousy. In addition, people respond to the misfortunes of these groups with schadenfreude, pleasure at the suffering of others,44 which also predicts harm. Specifically, when witnessing the misfortunes of members of these groups, people show activation of neural reward centers and display just barely detectable smiles (measured electromyographically from their zygomaticus [smile] muscles).45,46

People respond to these high-status but unsympathetic outsiders with passive help (going along) but active harm (backlash).26 That is, people will engage in obligatory contact as needed, but when conditions permit enacting their resentment, they may harm envied group members. Examples include individual sabotage in the workplace and group violence under political breakdown. In health care, potential indicators might include less active intervention or unnecessary invasive technological procedures.

Stereotypically high-warmth, high-competence groups.

Much of intergroup bias revolves around favoring “us” at the expense of “them,” rather than overtly negative treatment of “them.”8,47 In SCM data,25,26 society's reference groups constitute its default and aspirational groups for others outside this warm, competent quadrant. Middle-class Whites, Christians, and heterosexuals seem high on both warmth and competence. These groups elicit feelings of pride and admiration. Not surprisingly, they also receive both active and passive help.21 In US health care, Whites generally receive the most thorough, appropriate, and effective treatment.5

Health Care Implications of Distinct Biases

We are not aware of research that has applied SCM directly to understanding patterns of racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Nevertheless, knowing the principles of the model may enhance understanding of bias in health care and suggest directions for research.

The model offers specific predictions about the types of biases in health care that members of different groups might experience. We hypothesize, for example, that compared with high-warmth, high-competence groups (e.g., Whites),

Stereotypically high-warmth, low-competence groups (e.g., people with disabilities) are overrecommended for institutionalized care and receive low levels of emotional support48;

Stereotypically low-warmth, high-competence groups (e.g., Asians) are more likely to receive unnecessary surgical procedures or invasive technological procedures (e.g., defibrillators);

Stereotypically low-warmth, low-competence groups (e.g., undocumented immigrants, homeless people) receive less thorough care for nonemergency conditions5 but more aggressive surgical procedures for acute conditions.

EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT BIASES

Traditionally, stereotypes and prejudice have been conceptualized as explicit responses—beliefs and attitudes people know they hold and can control deliberately and strategically. By contrast to these explicit processes, implicit prejudices and stereotypes involve unintentional activation, often outside personal awareness.49 Implicit biases are most commonly measured with response–latency techniques, but are also assessed with neuroimaging or psychophysiological reactions.50 Implicit biases reflect not only general evaluative (good–bad) associations with a group51 but also associations with competence and warmth,52,53 and with specific stereotypical characteristics.54

Explicit Bias

Explicit bias still exists and is frequently expressed directly. Research on medical decision-making shows that physicians recommend more advanced and potentially more effective medical procedures (coronary bypass surgery) for White than for Black patients, and this disparity occurs because physicians assume that Black patients are less educated and less active.55

However, explicit biases are becoming much less common and are less prevalent among Whites with more education and higher socioeconomic status.56 Members of the medical community frequently assert that prejudice and stereotyping are rare in practice.57 Even when physicians do acknowledge that patients may be treated unfairly because of their race/ethnicity generally,58 they report that they do not discriminate in the care they personally provide.59

Implicit Bias

By contrast to fading overt racial/ethnic biases, implicit biases persist.60 These biases occur across educational and socioeconomic levels because they represent overlearned cultural associations61 with a strong affective basis62 that are difficult to completely overwrite with more recent experiences or acquired values.63 Implicit and explicit biases, which are only weakly related,50,51,64 often independently predict discriminatory actions.51,64

Most Whites currently disavow racial/ethnic prejudice and stereotypes and inhibit blatant discrimination. However, they often subtly express their implicit biases, for instance, by discriminating against Blacks when the guidelines for making a decision are not well specified.65 Racial/ethnic disparities in medical treatment also appear to be more pronounced when guidelines for treatment are not well defined (e.g., in treatment of pain66,67). In addition, Whites who possess egalitarian conscious beliefs but who harbor implicit prejudice (termed aversive racists65) tend to convey mixed messages—positive in content but undermined by negative, distancing nonverbal behaviors—in their intergroup interactions.68 Members of traditionally stigmatized groups, who may be vigilant for cues of bias,69 readily detect these signs.

Even though those in helping professions typically see themselves as unbiased, White physicians display strong implicit preferences for Whites over Blacks.70 For instance, White physicians who reported they believed Black patients were more adherent than White patients showed the opposite on an implicit measure.59 The distinction between explicit and implicit prejudice may be especially relevant to understanding biases in (1) medical decision-making and clinical communication by physicians and (2) patient perceptions of bias in medical encounters.

Physician Decision-Making and Behavior

Medical decision-making is obviously complex, and in decision-making, physicians rely heavily on information about differences in the incidence of conditions across patients sharing common characteristics, including race and ethnicity. The line between basing decisions on these group differences and basing them on overgeneralized expectations and assumptions in unfair, stereotypical ways is thin, and physicians (and other medical personnel) sometimes make stereotypical inferences (beyond what is warranted by data) derived from a patient's race or ethnicity.55,71 Also, medical decision-making frequently occurs when providers are burdened or fatigued, limiting cognitive control for inhibiting bias and thus increasing the influence of implicit relative to explicit forms of bias.

Despite evidence in the psychological literature that implicit biases systematically predict discrimination—often better than explicit attitudes51—only limited evidence directly documents their influence in medical contexts. In a vignette study about cardiology patients,72 physicians reported no explicit biases against Black relative to White patients. However, physicians had more negative implicit attitudes toward Blacks than toward Whites and stronger stereotypes of Blacks as uncooperative patients. The more negative their implicit attitudes, the less likely they were to recommend thrombolytic drugs for Black patients.

The quality of communication is lower in interracial medical interactions than in same-race encounters: the former are less patient centered73 and less positive.73,74 Physicians’ implicit biases likely contribute to this effect. In a recent study,75 Black patients perceived physicians who had more implicit bias (assessed with the Implicit Association Test51) as less warm and friendly in their encounter; this effect was distinct from any effect of the physician's level of explicit prejudice. In addition, Black patients feel less respected by the physician, like the physician less, and have less confidence in the physician regarding their medical encounters when the physician exhibits greater implicit racial bias.76

Patient Attitudes, Expectations, and Biases

Medical interactions also have to be considered within a larger social context. Experiences of discrimination outside the clinical encounter not only relate to poorer health generally77–81 but also are associated with perceptions of bias in medical interactions.82

Overall, racial/ethnic minorities are significantly more likely than Whites to believe that their race negatively affects their health care83,84 and are less trusting of their physicians.85,86 These perceptions of bias correlate with and predict Black patients’ less positive behavior in medical interactions, more negative views of their physician, and less favorable evaluations of the quality of their care.87–89 Greater mistrust of the health care system90 and experiences of bias in medical encounters, whether accurate or not, can reduce use of health care services91 and erode confidence in the prescribed medical regimen, leading to lower levels of medical adherence,92,93 less utilization of preventive services,94–96 and ultimately, poorer health.

The influence of implicit bias on providers’ racial bias may be particularly detrimental to health care interactions in a climate of distrust. The ambivalent nature of contemporary racial prejudice may create a mismatch between a physician's positive verbal behavior (as a function of conscious egalitarian values) and negative nonverbal behavior (indicating implicit bias); this is likely to make a physician seem especially untrustworthy and duplicitous to those who are vigilant for cues of bias. Indeed, Black patients who interacted with physicians low in explicit prejudice but high in implicit prejudice (those more likely to convey mixed messages verbally and nonverbally) were less satisfied with their medical encounter than were their counterparts encountering physicians with any other combination of implicit and explicit attitudes, including those uniformly high on both explicit and implicit bias.75

COMBATING BIAS IN HEALTH CARE

Although racial and ethnic disparities in health can be caused by several factors other than bias in health care—and are largely attributed to these other factors97—discrimination in health care plays a significant role. Traditional views and lay theories have emphasized prejudice as a uniform, intentional antipathy, but contemporary psychological science paints a more complex and nuanced picture. People direct distinct forms of bias toward different out-groups. Moreover, despite the fact that most health care professionals consciously embrace egalitarian values, implicit biases can shape what they do. One proposal for reducing bias in health care is to increase the diversity of the health care workforce, but minority health care providers also tend to be victimized by discrimination in the workplace.98,99 Recognizing the potential influence of implicit responses, both cognitive and affective, toward specific groups defined by their position in the 2 × 2 competence–warmth map may help guide interventions to reduce bias in health care.

Discriminatory behavior, even when shaped by automatically activated prejudice and stereotypes, is not inevitable. With sufficient knowledge, motivation, skill, and cognitive resources, people can control the expression of prejudice and stereotypes in their actions.100 When medical students were presented with relatively straightforward medical vignettes with minimal other demands on their cognitive resources, implicit prejudice did not affect medical decision-making, and respondents did not discriminate overall.101 However, to engage effectively in self-regulation, people have to be aware of the complex nature of bias, understand that various emotions (e.g., pity) and orientations (e.g., paternalism) are forms of bias, and recognize that they may have implicit biases that may be manifested subtly. Awareness of these elements is not sufficient, however; efforts simply to suppress bias can ironically activate stereotypical thoughts and interfere with effective communication across social boundaries.69 Thus, focusing primarily on people's intentions may not be particularly effective.

Interventions are most likely to be effective when they occur at multiple levels. First, people need to recognize that provider discrimination contributes significantly to health care disparities.102 Despite the epidemiological evidence,103 only 55% of White physicians agree that “minority patients generally receive lower quality care than White patients.”104 Subtle bias is much more difficult to recognize in a specific instance than when patterns are aggregated across cases,105 and providers may be motivated to dismiss indications of bias in their personal practice. Thus, systematically collecting data that could implicate the operation of subtle, distinct biases is critical for addressing the problem.106

Second, once providers understand the complex nature of contemporary bias and the nuances of stereotyping and affective responses, they may be better equipped to provide higher-quality care more equitably. Medical education might also offer clinicians additional tools for counteracting the influence of potential bias. Whereas strategies directed at preventing bias by suppressing stereotypes may backfire, those aimed at promoting positive relations can inhibit the activation of implicit bias.107 When people focus on common group memberships (e.g., shared organizational or national identities) instead of different racial or ethnic identities, members of racial and ethnic majority and minority groups spontaneously reduce racial or ethnic bias and experience greater trust.108 Although race and ethnicity are cultural default categories psychologically, reframing of this type can change how people think about others in ways that do not activate cultural stereotypes.109 Interventions that lead people to think of themselves as a team reduce the activation of racial/ethnic stereotypes and, in medical contexts, produce more positive doctor–patient interactions.110

Third, providers can develop new mental habits. Self-regulation of bias, with sufficient practice, can become automatic: although implicit biases may not be eliminated altogether, they may be overridden by new, incompatible implicit egalitarian motives and goals.111,112 Thus, training might involve not only the development of culturally competent skills but also direct experiences to develop effective (and potentially automatic) self-regulation to mitigate subtle bias. Because the nature of bias differs cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally across various targets, biases toward different groups cannot be fully addressed with training and intergroup experiences involving only 1 group. More work bridging the psychological literature and medical practice may offer new theoretical insights and practical ways to combat bias in health care.

Acknowledgments

John F. Dovidio received support from the National Institutes of Health (grant RO1HL0856331-0182) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant 1R01DA029888-01).

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Institutes of Health and the encouragement and guidance of Vickie Shavers on this project.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed because human participants were not involved.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics Healthy People 2010. Hyattsville, MD: Government Printing Office; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mead H, Cartwright-Smith L, Jones K, Ramos C, Woods C, Siegel B. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in U.S. Healthcare: A Chartbook. Winston-Salem, NC: Wake Forest University School of Medicine [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orisi JM, Margellos-Anast H, Whitman S. Black–White health disparities in the United States and Chicago: a 15-year progress analysis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):349–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Orom H, Coleman DK, Underwood W., III Health and health care disparities. : Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM, Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. London, UK: Sage; 2010:472–490 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dovidio JF, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Norton WE, Gaertner SL, Shelton JN. Disparities and distrust: the implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):478–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhoads KF, Cullen J, Ngo JV, Wren SM. Racial and ethnic differences in lymph node examination after colon cancer resection do not completely explain disparities in mortality. Cancer. 2012;118(2):469–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Intergroup bias. : Fiske ST, Gilbert D, Lindzey G, Handbook of Social Psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 2010:1084–1121 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM. Prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination: theoretical and empirical overview. : Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM, Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. London, UK: Sage; 2010:3–28 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiske ST. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. : Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, Handbook of Social Psychology. Vol 2, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1998:357–411 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weng Y, Korte JE. Racial disparities in being recommended for oral and oropharyngeal cancer in the United States. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(1):80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livaudais JC, Hershman DL, Habel L, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in initiation of adjuvant hormonal therapy among women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(2):607–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CN, Ko CY. Beyond outcomes—the appropriateness of surgical care. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1580–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith ER, Mackie DM. Affective processes. : Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM, Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. London, UK: Sage; 2010:131–145 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abele AE, Cuddy AJC, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. Fundamental dimensions of social judgment. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2008;38(7):1063–1065 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abele AE, Wojciszke B. Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93(5):751–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Judd CM, James-Hawkins L, Yzerbyt VY, Kashima Y. Fundamental dimensions of social judgment: understanding the relations between judgments of competence and warmth. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89(6):899–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wojciszke B. Morality and competence in person- and self-perception. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2005(1);16:155–188 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. Competence and warmth as universal trait dimensions of interpersonal and intergroup perception: the Stereotype Content Model and the BIAS map. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2008;40:61–149 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiske ST. Envy Up, Scorn Down: How Status Divides Us. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P. Universal dimensions of social perception: warmth and competence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11(2):77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kervyn N, Yzerbyt VY, Demoulin S, Judd CM. Competence and warmth in context: the compensatory nature of stereotypic views of national groups. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2008;38(7):1175–1183 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kervyn N, Yzerbyt VY, Judd CM, Nunes A. A question of compensation: the social life of the fundamental dimensions of social perception. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96(4):828–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(6):878–902 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. The BIAS map: behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(4):631–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clausell E, Fiske ST. When do subgroup parts add up to the stereotypic whole? Mixed stereotype content for gay male subgroups explains overall ratings. Soc Cogn. 2005;23(2):161–181 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris LT, Fiske ST. Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: neuroimaging responses to extreme out-groups. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(10):847–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell AMT, Fiske ST. It's all relative: competition and status drive interpersonal perception. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2008;38(7):1193–1201 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maddox KB. Perspectives on racial phenotypicality bias. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;8(4):383–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gluszek A, Dovidio JF. The way they speak: a social psychological perspective on the stigma of nonnative accents in communication. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2010;14(2):214–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steele CM. A threat in the air: how stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am Psychol. 1997;52(6):613–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talaska CA, Fiske ST, Chaiken S. Legitimating racial discrimination: emotions, not beliefs, best predict discrimination in a meta-analysis. Soc Justice Res. 2008;21(3):263–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asbrock F. Stereotypes of social groups in Germany in terms of warmth and competence. Soc Psychol. 2010;41(2):76–81 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guan Y, Deng H, Bond MH. Examining stereotype content model in a Chinese context: inter-group structural relations and Mainland Chinese's stereotypes towards Hong Kong Chinese. Int J Intercult Relat. 2010;34(4):393–399 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bliss TK, Blum CM, Bulanda J, Cella AM. Racial perceptions of homelessness: a Chicago-based study investigating racial bias. Praxis. 2004;4:36–44 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hogg MA. Self-categorization theory. : Levine JM, Hogg MA, Encyclopedia of Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. Vol 2 Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010:728–731 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris LT, Fiske ST. Social neuroscience evidence for dehumanized perception. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2009;20(1):192–231 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiner B. The development of an attribution-based theory of motivation: a history of ideas. Educ Psychol. 2010;45(1):28–36 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green A. Attacks on homeless rise, with youths mostly to blame. New York Times. February 15, 2008:A12. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/15/us/15homeless.html. Accessed November 2, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyon J. Update: House panel rejects bill to deny services to illegal immigrants. Arkansas News. February 23, 2011. Available at: http://arkansasnews.com/2011/02/23/house-panel-rejects-bill-to-deny-services-to-illegal-immigrants. Accessed November 2, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, Phelan S, van Ryn M. The effect of medical authoritarianism on physicians' treatment decisions and attitudes regarding chronic pain. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2011;41(6):1399–1420 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Langer EJ, Rodin J. The effects of choice and enhanced personal responsibility for the aged: a field experiment in an institutional setting. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1976;34(2):191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leach CW, Spears R, Branscombe NR, Doosje B. Malicious pleasure: schadenfreude at the suffering of another group. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(5):932–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cikara M, Botvinick MM, Fiske ST. Us versus them: social identity shapes neural responses to intergroup competition and harm. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(3):306–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cikara M, Fiske ST. Stereotypes and Schadenfreude: Affective and physiological markers of pleasure at outgroup misfortunes. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2012;3(1):63–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yzerbyt V, Demoulin S. Intergroup relations. : Fiske ST, Gilbert D, Lindzey G, Handbook of Social Psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 2010:1024–1083 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Havercamp SM, Scandlin D, Roth M. Health disparities among adults with developmental disabilities, adults with other disabilities, and adults not reporting disability in North Carolina. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(4):418–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fazio RH, Olson MA. Implicit measures in social cognition research: their meaning and uses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54:297–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dovidio JF, Kawakami K, Beach KR. Implicit and explicit attitudes: examination of the relationship between measures of intergroup bias. : Brown R, Gaertner SL, Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology. Vol 4 Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2001:175–197 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann EL, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):17–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carlsson R, Björklund F. Implicit stereotype content: mixed stereotypes can be measured with the implicit association test. Soc Psychol. 2010;41(4):213–222 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rudman LA, Glick P. Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. J Soc Issues. 2001;57(4):743–762 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blair IV. Implicit stereotypes and prejudice. : Moskowitz GB, Cognitive Social Psychology: The Princeton Symposium on the Legacy and Future of Social Cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001: 359–374 [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Ryn M, Burgess DJ, Malat J, Griffin J. Physicians’ perceptions of patients’ social and behavioral characteristics and race disparities in treatment recommendations for men with coronary artery disease. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):351–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bobo L. Racial attitudes and relations at the close of the twentieth century. : Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, Racial Trends and Their Consequences. Vol 1 Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001:264–301 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Epstein RA. Disparities and discrimination in health care coverage: a critique of the Institute of Medicine study. Perspect Biol Med. 2005;48(1 Suppl):S26–S41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaiser Family Foundation National survey of physicians part I: doctors on disparities in medical care. Available at: http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/20020321a-index.cfm. Accessed February 25, 2011

- 59.Sabin JA, Rivara FP, Greenwald AG. Physician implicit attitudes and stereotypes about race and quality of medical care. Med Care. 2008;46(7):678–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nosek BA, Smyth FL, Hansen JJ, et al. Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2007;18(1):36–88 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karpinski A, Hilton JL. Attitudes and the Implicit Association Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(5):774–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rudman LA. Sources of implicit attitudes. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2004;13(2):79–82 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson TD, Lindsey S, Schooler TY. A model of dual attitudes. Psychol Rev. 2000;107:101–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dovidio JF, Kawakami K, Smoak N, Gaertner SL. The roles of implicit and explicit processes in contemporary prejudice. : Petty RE, Fazio RH, Brinol P, Attitudes: Insights From the New Implicit Measures. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2009:165–192 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Aversive racism. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2004;36:1–52 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burgess DJ, van Ryn M, Crowley-Matoka M, Malat J. Understanding the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in pain treatment: insights from dual process models of stereotyping. Pain Med. 2006;7(2):119–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Geiger HJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in diagnosis and treatment: a review of the evidence and a consideration of causes. : Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003:417–454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dovidio JF, Kawakami K, Gaertner SL. Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):62–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Richeson JA, Shelton JN. Prejudice in intergroup dyadic interactions. : Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM, Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. London, UK: Sage; 2010:276–293 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sabin JA, Nosek BA, Greenwald AG, Rivara FP. Physicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about race by MD race, ethnicity, and gender. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):896–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hirsh AT, Jensen MP, Robinson ME. Evaluation of nurses’ self-insight into their pain assessment and treatment decisions. J Pain. 2010;11(5):454–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for Black and White patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1231–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):101–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, West TV, et al. Aversive racism and medical interactions with Black patients: a field study. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46(2):436–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cooper LA. Patient-client and perceived discrimination in health care. Paper presented at: Science of Research on Discrimination and Health Conference; February 3, 2011; National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brondolo E, Hausmann LR, Jhalani J, et al. Dimensions of perceived racism and self-reported health: examination of racial/ethnic differences and potential mediators. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(1):14–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:381–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional and individual racial discrimination and health status. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9 Suppl):S48–S56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hausmann LR, Jeong K, Bost JE, Ibrahim SA. Perceived discrimination in health care and health status in a racially diverse sample. Med Care. 2008;46(9):905–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Otiniano AD, Gee GC. Self-reported discrimination and health-related quality of life among Whites, Blacks, Mexicans and Central Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012; Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Edmondson D, et al. The experience of discrimination in Black–White health disparities in medical care. J Black Psychol. 2009;35(2):180–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr, Sharf BF, Kelly PA, Souchek J. Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients’ perceptions of physician communication. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):904–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malat J, Hamilton MA. Preference for same-race health care providers and perceptions of interpersonal discrimination in health care. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47(2):173–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Halbert CH, Armstrong K, Gandy OH, Jr, Shaker L. Racial differences in trust in health care providers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8):896–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kennedy BR, Mathis CC, Woods AK. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: healthcare for diverse populations. J Cult Divers. 2007;14(2):56–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Benkert R, Peters RM, Clark R, Keves-Foster K. Effects of perceived racism, cultural mistrust and trust in providers on satisfaction with care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(9):1532–1540 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guadagnolo BA, Cina K, Helbig P, et al. Medical mistrust and less satisfaction with health care among Native Americans presenting for cancer treatment. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(1):210–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hausmann LR, Hannon MJ, Kresevic DM, Hanusa BH, Kwoh CK, Ibrahim SA. Impact of perceived discrimination in healthcare on patient-provider communication. Med Care. 2011;49(7):626–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nguyen DD, Ho KH, Williams JH. Social determinants of health service use among racial and ethnic minorities: findings from a community sample. Soc Work Health Care. 2011;50(5):390–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Musa D, Schilz R, Harris R, Silverman M, Thomas SB. Trust in the health care system and the use of preventive health services by older Black and White adults. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(7):1293–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Blanchard J, Lurie N. R-E-S-P-E-C-T: patient reports of disrespect in the health care setting and its impact on care. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(9):721–730 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Cooper LA. Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):389–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Crawley LM, Ahn DK, Winkleby MA. Perceived medical discrimination and cancer screening behaviors of racial and ethnic minority adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(8):1937–1944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hausmann LR, Jeong K, Bost JE, Ibrahim SA. Perceived discrimination in health care and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1679–1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mouton CP, Carter-Nolan PL, Makambi KH, et al. Impact of perceived racial discrimination on health screening in Black women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1):287–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim AE, Kumanyika S, Shive D, Igweatu U, Kim S-H. Coverage and framing of racial and ethnic disparities in US newspapers, 1996–2005. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S224–S231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Coombs AA, King RK. Workplace discrimination: experiences of practicing physicians. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(4):467–477 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nunez-Smith M, Pilgrim N, Wynia M, et al. Health care workplace discrimination and physician turnover. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(12):1274–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dasgupta N, Rivera LM. From automatic antigay prejudice to behavior: the moderating role of conscious beliefs about gender and behavioral control. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(2):268–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Haider AH, Sexton J, Sriram N, et al. Association of unconscious race and social class bias with vignette-based clinical assessments by medical students. JAMA. 2011;306(9):942–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):654–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Satcher D, Higginbotham EJ. The public health approach to eliminating disparities in health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):400–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Commission to End Health Care Disparities Quality health care for minorities: understanding physicians’ experiences. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/public-health/eliminating-health-disparities/commission-end-health-care-disparities/quality-health-care-minorities-understanding-physicians.shtml. Accessed February 25, 2011

- 105.Crosby F, Clayton S, Alksnis O, Hemker K. Cognitive biases in the perception of discrimination: the importance of format. Sex Roles. 1986;14(11–12):637–646 [Google Scholar]

- 106.van Ryn M, Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, et al. The impact of racism on clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision making. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):199–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Betancourt JR, Green AR. Commentary: linking cultural competence training to improved health outcomes: perspectives from the field. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):583–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF. Reducing Intergroup Bias: The Common Ingroup Identity Model. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wheeler ME, Fiske ST. Controlling racial prejudice and stereotyping: social-cognitive goals affect amygdala and stereotype activation. Psychol Sci. 2005;16(1):56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Penner LA, Dailey R, Markova T, Porcerelli J, Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Using the Common Group Identity Model to increase trust and commonality in racially discordant medical interactions. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of Society of Personality and Social Psychology; February 6, 2009; Tampa, FL [Google Scholar]

- 111.Moskowitz GB. On the control of stereotype activation and inhibition. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2010;4(2):140–158 [Google Scholar]

- 112.Monteith MJ, Arthur SA, Flynn SM. Self-regulation and bias. : Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM, Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. London, UK: Sage; 2010:93–507 [Google Scholar]