Abstract

Background

In Europe, only a limited number of cross-cultural comparative field studies or meta-analyses have been focused on the dynamics through which folk plant knowledge changes over space and time, while a few studies have contributed to the understanding of how plant uses change among newcomers. Nevertheless, ethnic minority groups and/or linguistic “isles” in Southern and Eastern Europe may provide wonderful arenas for understanding the various factors that influence changes in plant uses.

Methods

A field ethnobotanical study was carried out in Mundimitar (Montemitro in Italian), a village of approx. 450 inhabitants, located in the Molise region of South-Eastern Italy. Mundimitar is a South-Slavic community, composed of the descendants of people who migrated to the area during the first half of the 14th century, probably from the lower Neretva valley (Dalmatia and Herzegovina regions). Eighteen key informants (average age: 63.7) were selected using the snowball sampling technique and participated in in-depth interviews regarding their Traditional Knowledge (TK) of the local flora.

Results

Although TK on wild plants is eroded in Montemitro among the youngest generations, fifty-seven taxa (including two cultivated species, which were included due to their unusual uses) were quoted by the study participants. Half of the taxa have correspondence in the Croatian and Herzegovinian folk botanical nomenclature, and the other half with South-Italian folk plant names. A remarkable link to the wild vegetable uses recorded in Dalmatia is evident. A comparison of the collected data with the previous ethnobotanical data of the Molise region and of the entire Italian Peninsula pointed out a few uses that have not been recorded in Italy thus far: the culinary use of boiled black bryony (Tamus communis) shoots in sauces and also on pasta; the use of squirting cucumber ( Ecballium elaterium) juice for treating malaria in humans; the aerial parts of the elderberry tree ( Sambucus nigra) for treating erysipelas in pigs; the aerial parts of pellitory ( Parietaria judaica) in decoctions for treating haemorrhoids.

Conclusions

The fact that half of the most salient species documented in our case study – widely available both in Molise and in Dalmatia and Herzegovina – retain a Slavic name could indicate that they may have also been used in Dalmatia and Herzegovina before the migration took place. However, given the occurrence of several South-Italian plant names and uses, also a remarkable acculturation process affected the Slavic community of Montemitro during these last centuries. Future directions of research should try to simultaneously compare current ethnobotanical knowledge of both migrated communities and their counterparts in the areas of origin.

Keywords: Ethnobotany, Wild food plants, Montemitro, Molise-Slavic, Molise

Introduction

One of the most intriguing scientific questions in ethnobiology concerns the ways through which folk plant knowledge changes over space and time. In Europe, only a limited number of cross-cultural comparative field studies or meta-analyses of historical ethnobotanical literature focused on such dynamics so far [1-8], while an increasing number of studies have contributed to the understanding of how plant uses change among “newcomers” [9-17].

Ancient linguistic diasporas have instead been the focus of several field ethnobotanical surveys in Italy during the last decades. Studies on Traditional Knowledge (TK) of plant uses have thus far involved a number of ethnic minority groups within the Italian geographical region: in Northern Italy, Occitans (Provençal) [18-23], Franco-Provençal [20,24-26] and German Walser [27-29] groups in Piedmont, Ladins [30-33], Mócheno [34] and Cimbrian [35,36] Bavarians in Veneto and Trentino; Istro-Romanians in the Croatian Istria [37]; in Southern Italy: Albanian Arbëreshë in Lucania [38-40] and Greeks in Calabria [41,42]; in Sardinia, Tabarkins (Ligurians) [43].

The present study focused on the food and herbal ethnobotany of an ancient South-Slavic diaspora living in the village of Mundimitar/Montemitro, Molise Region, South-Eastern Italy.

The aims of this study were:

· to record folk food and herbal uses of wild plants and mushrooms in Mundimitar;

· to compare the collected ethnolinguistic data with those of Molise, surrounding Italian regions and of Croatia and Herzegovina;

· to compare the recorded ethnobotanical uses with all Italian ethnobotanical literature;

· to assess the resilience and cultural adaptations of the Slavic diaspora in perceptions (naming) and uses of wild plants.

Methodology

Study site

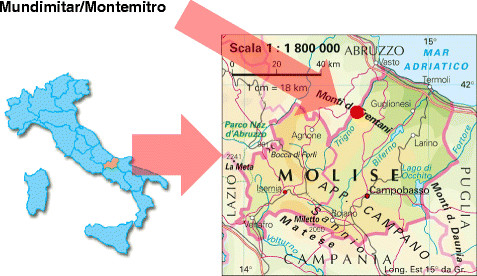

Mundimitar (in Italian Muntemitro) is a small village located at 508 m.a.s.l. in the Province of Campobasso, Molise Region, Southern Italy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of Mundimitar/Montemitro.

Like Acquaviva Collecroce and San Felice del Molise, Montemitro is the home to a Slavic community that migrated in the area, probably from the lower Neretva valley (Dalmatia and Herzegovina regions) during the first half of the 14th century [44].

The village had a population of ca. 1,000 inhabitants until the 1970’s when many locals migrated to Northern Italy or abroad for employment. Nowadays, the village is composed of ca. 450 inhabitants who speak a Western Štokavian dialect (na-našo in the local language, meaning “in our language”), known by linguists as Molise Slavic or Molise Croatian.

Field study

The field ethnobiological study was carried out in Mundimitar during several visits in 2009 and 2010. Eighteen key informants (average age: 63.7) were selected using snowball sampling techniques and participated in in-depth interviews regarding their TK of the local flora. The focus of the interviews was on folk food and medicinal uses of wild food plants and mushrooms. Prior informed consent (PIC) was obtained verbally before commencing each interview and the guidelines of the AISEA (Italian Association for Ethno-Anthropological Sciences) [45] were adhered to.

Free-listing and semi-structured interview techniques were used. When available, the wild plant species cited during interviews were collected, verified by our interviewees, identified according to Pignatti’s Flora d’Italia[46], named according to Tutin et al.’s Flora Europaea[47] and later deposited at the Herbarium of the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Pollenzo. Plant family names follow the recent classification (III) of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. The local folk plant names cited during interviews were recorded and transcribed in Serbo-Croatian (after the Yugoslav dissolved, also named BCSM – Bosnian/Bosniak-Croatian-Serbian-Montenegrin).

Data analysis

The data collected during the field study were sorted in Microsoft® Excel.

Two in-depth comparisons were conducted:

· the former, concerning folk plant names, with the standard work on Croatian and Italian folk phytonimy [48,49], a comprehensive review of the food ethnobotany of Abruzzo (the Italian region bordering Molise) [50], and unpublished ethnobotanical data of SR from Herzegovina as well as the unpublished list of wild food plants sold in the main eleven Dalmatian vegetable markets in March 2012 (ŁŁ);

· the latter, concerning the folk plant uses, with the most comprehensive review of the Italian ethnobotany (published in 2006) [51] and a few additional recent ethnobotanical field studies conducted in the Molise region [52-55]. Data from the studied village concerning wild green vegetables were compared with Croatian literature concerning plants use in Dalmatia [56-59] and with personal (ŁŁ ) observations on wild vegetables sold in Dalmatian markets in 2012.

Results and discussion

Table 1 shows the local food and medicinal uses of wild vascular plants and mushrooms recorded in Montemitro. Fifty-seven species were identified by study participants. The table includes also the unusual food uses of two cultivated species (garlic and lupine). The limited number of identified fungi is attributed to the fact that most of the cited folk names did not occur during the visit in the field and could not be clearly identified.

Table 1.

Traditional food and medicinal uses of wild plants and mushrooms in Mundimitar/Montemitro

| Botanical taxon and family | Local name(s) in Mundimitar | English name | Part(s) used | Folk use(s) in Mundimitar | Frequency of citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Allium sativum L. (Amaryllidaceae) (CULTIVATED) |

Luk |

Garlic |

Flowering shoots |

Boiled, then preserved in olive oil or vinegar; in tomato sauces |

+++ |

|

Amaranthus retroflexus L. (Amaranthaceae) |

Pjedruš |

Amaranth |

Leaves |

Raw in salads, or boiled |

+++ |

|

Apium nodiflorum (L.) Lag. (Apiaceae) |

Kanijola |

Fool's water-cress |

Aerial parts |

Raw in salads or between two slices of bread |

+++ |

|

Armillaria mellea (Vahl) P. Kumm and related species (Marasmiaceae) |

Rekkie mušil |

Honey fungus |

Fruiting body |

Blanched, then fried |

+ |

|

Asparagus acutifolius L. (Asparagaceae) |

Sparuga |

Wild asparagus |

Shoots |

Boiled, then fried in omelets |

+++ |

|

Beta vulgaris subsp. maritima (L.) Arcang. (Amaranthaceae) |

Blitva |

Wild beet |

Leaves |

Boiled, then fried |

+++ |

|

Borago officinalis L. (Boraginaceae) |

Bureina |

Borage |

Young leale |

Boiled. |

+++ |

| Coated with bread crumbs, then deep fried | |||||

|

Bunias erucago L. (Brassicaceae) (?) |

Rapanača |

Crested warty cabbage |

Whorls |

Boiled and fried |

+ |

|

Calendula arvensis L. (Asteraceae) |

Kalendula |

Marigold |

Flowers |

In salads |

+ |

|

Cantharellus cibarius Fr. (Cantharellaceae) |

Galuč |

Chanterelle |

Fruiting body |

Blanched, then fried |

+ |

|

Centaurium erythraea Rafn. (Gentianaceae) |

Džencjanela |

Centaury |

Aerial parts |

Decoction as a panacea |

+ |

|

Cichorium intybus L. (Asteraceae) |

Čikoria |

Wild cichory |

Whorls |

Boiled, then fried in olive oil with garlic |

++ |

|

Clavaria sp. (Clavariaceae) |

Picele |

Coral fungus |

Fruiting body |

Boiled, then fried |

+ |

|

Clematis vitalba L. (Ranunculaceae) |

Škrabut |

Traveller’s joy |

Shoots |

Boiled, then fried or in sauces; digestive aid |

+++ |

| Stems are directly applied on the tooth to treat toothache | |||||

|

Cornus mas L. (Cornaceae) |

Kurnja |

Cornel cherry tree |

Fruits (Kurnjal) |

Consumed raw, or dried/smoked; liqueurs |

+++ |

|

Crataegus. monogyna Jacq. and C. oxyacantha L. (Rosaceae) |

Glog |

Hawthorn |

Fruits (Glogbili) |

Consumed raw as snack. |

+++ |

| The thorny stems were used to insert into figs for drying. | |||||

|

Cydonia oblonga Mill. (Rosaceae) |

Kutunja |

Quince |

Fruits |

Boiled with wine, for treating sore throats. |

+++ |

| Jam. | |||||

|

Cynara cardunculus L. (Asteraceae) |

Ošnak |

Wild artichocke or wild cardoon |

Stems |

Boiled, then fried with eggs |

+++ |

|

Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. (Poaceae) |

Gramača |

Bermuda grass |

Whole plant |

Decoction as a diuretic |

++ |

|

Diplotaxis erucoides (L.) DC. (Brassicaceae) |

Marijun |

White wall-rocket |

Leaves |

Raw in salads, more often fried in the pan |

+++ |

|

Ecballium elaterium (L.) A. Rich. (Cucurbitaceae) |

Tikvica divlja |

Squirting cucumber |

Fruit juice |

Instilled in the nose for treating malaria or spread on women breast for weaning babies |

++ |

|

Eruca sativa Miller (Brassicaceae) |

Rucola |

Rocket |

Leaves |

Raw in salads |

+++ |

|

Eryngium campestre L. (Apiaceae) (?) |

Sikavac |

Field eryngo |

Leaves |

Decoction for treating eye inflammations |

+ |

|

Ficus carica L. (Moraceae) |

Smokva |

Fig tree |

Pseudofruits |

Eaten fresh or dried |

+++ |

|

Foeniculum vulgare Mill. subsp. piperitum (Ucria) Cout. (Apiaceae) |

Finoč |

Wild fennel |

Fruits |

Seasoning for home-made sausages; decoctions as diuretic or for treating gastric reflux |

+++ |

|

Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (Fabaceae) |

Gurgulica |

Licorice |

Root |

Consumed raw as snack. |

+++ |

| The aerial parts used as insect repellent. | |||||

|

Humulus lupulus L. (Cannabaceae) |

Lupare |

Wild hop |

Shoots |

Boiled, then fried in omelet |

++ |

|

Hydnum repandum L.: Fr. (Hydnaceae) |

Lengaove |

Wood hedgehog |

Fruiting body |

Blanched, then fried |

++ |

|

Lupinus albus L. spp. (Fabaceae) (CULTIVATED) |

Lupino |

Lupin |

Flower shoots Aerial parts |

Boiled, then fried. |

+ |

| The decoction of the whole aerial parts is used in external washes for treating pig erysipelas | |||||

|

Malva sylvestris L. (Malvaceae) |

Slis |

Mallow |

Leaves and flowers |

Decoction for treating digestive troubles, bronchitis, or as a laxative for children |

+++ |

|

Matricaria chamomilla L. (Asteraceae) |

Kamomilla |

Chamomile |

Flowering tops or stems |

Decoction, as a mild tranquillizer |

++ |

|

Mercurialis annua L. (Euphorbiaceae) |

Merkulela |

Mercurya |

Leaves |

Boiled in soups (mixed with other herbs), or in purgative decoctions |

++ |

|

Olea europaea L. var. sylvestris Brot. (Oleaceae) |

Maslina |

Wild olive tree |

Branches |

Used for drying figs |

++ |

|

Origanum vulgare L. (Lamiaceae) |

Pljei |

Wild oregano |

Flowering tops |

Seasoning |

+++ |

|

Papaver rhoeas L. (Papaveraceae) |

Mak |

Corn poppy |

Young aerial parts |

Raw in salads, or cooked |

+++ |

|

Parietaria judaica L. (Urticaceae) |

Kolana |

Pellitory |

Aerial parts |

Decoction in external use for treating hemorrhoids (affected parts exposed to vapors). |

++ |

| Necklaces for children | |||||

|

Picris echioides L. and P. hieracioides L. (Asteraceae) |

Tustača |

Oxtongue |

Whorls and shoots |

Shoots eaten raw as snack. |

++ |

| Whorls boiled and fried. | |||||

|

Portulaca oleracea L. (Portulacaceae) |

Prkatj |

Purslane |

Aerial parts |

Raw in salads |

++ |

|

Prunus spinosa L. (Rosaceae) |

Ndrnjela |

Sloe |

Fruits |

Gathered an consumed after the frost; liqueurs |

++ |

|

Punica granatum L. (Punicaceae) |

Šipak |

Pomegranate |

Fruits |

Consumed raw in winter |

++ |

|

Pyrus pyraster Burgsd. (Rosaceae) |

Trnovača |

Wild pear tree |

Fruits |

Gathered and consumed after the frost |

++ |

|

Quercus virgiliana (Ten.) Ten. (Fagaceae) (?) |

Sladul |

Oak |

Kernel |

Consumed raw |

+ |

|

Rosa canina L. (Rosaceae) |

Skorčavata |

Dog rose |

Pseudofruits |

Decoction for treating sore throat (sometimes together wild dried figs, apple slices, and barley) |

+++ |

|

Ruscus aculeatus L. (Asparagaceae) |

Leprencia |

Butcher’s Broom |

Shoots |

Boiled, then fried. |

++ |

| Dried branches were used to clean the fireplace | |||||

|

Ruta graveolens L. (Rutaceae) |

Ruta |

Rue |

Aerial parts |

Aromatizing grappa. |

+++ |

| Kept under the pillow for treating worms in children. | |||||

| A few leaves eaten raw by pregnant women to prevent miscarriage (in the past) | |||||

|

Salvia verbenaca L. (Lamiaceae) |

Prsenica |

Meadow sage |

Leaves |

Applied externally with pork fat as a suppurative or for treating insect stings |

+ |

|

Sambucus nigra L. (Caprifoliaceae) |

Baz |

Elderbery tree |

Aerial parts and fruits |

Decoction, then in external washes for treating erysipelas in pigs. |

+++ |

| Fruits juice used as ink in the past. | |||||

|

Sinapis alba L and S. arvensis L. (Brassicaceae) |

Sinapa |

Wild mustard |

Young aerial parts |

Raw in salads, more often cooked in the pan |

++ |

|

Sonchus arvensis L. and S. oleraceus L. (Asteraceae) |

Kostriš/ Kašgn |

Sow thistle |

Young aerial parts |

Boiled, then fried in the pan or cooked in tomato sauce |

+++ |

|

Sorbus domestica L. (Rosaceae) |

Oskoruša |

Service tree |

Fruits |

Consumed after natural fermentation |

++ |

|

Stellaria media (L.) Vill. (Caryophyllaceae) |

Mišakina |

Chickweed |

Aerial parts |

Fodder for hens |

++ |

|

Tamus communis L. (Dioscoreaceae) |

Gljuštre |

Black bryony |

Shoots |

Boiled, then fried in the pan with eggs or tomato sauce (sometimes served on noodles) |

+++ |

|

Teucrium chamaedrys L. (Lamiaceae) |

Kametr |

Wall germander |

Aerial parts |

Decoction for treating malaria (in the past) and hypertension |

++ |

|

Umbilicus rupestris (Salisb.) Dandy (Crassulaceae) |

Kopič |

Navelwort |

Leaves |

Crushed and mixed with pork fat and soot for treating furuncles |

++ |

|

Urtica dioica L (Urticaceae) |

Kopriva |

Nettle |

Leaves and shoots |

Boiled, then mixed with ricotta cheese, in filled pasta. |

+++ |

| Decoction in external washes for strengthening the hair | |||||

|

Ziziphus jujuba Miller (Rhamnaceae) |

Džurdžula | Jujube | Fruits | Eaten after natural fermentation | + |

(?) Identification was only postulated on the basis of linguistic data and plant description; +++: quoted by 7 informants or more; ++: quoted by 2 to 6 informants; +: quoted by 1 or 2 informants only.

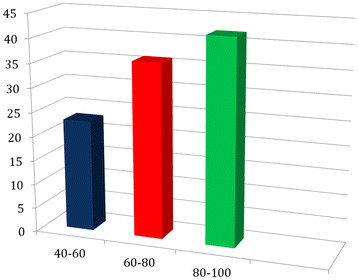

Figure 2 shows that TK on wild plants is eroded in Montemitro among the youngest generations, thus confirming trends that are the similar throughout Southern Europe and in a large part of the world.

Figure 2.

Average number of species quoted by informants by age.

Table 2 shows the ethnolinguistic comparative analysis of the most quoted species during the free-listing exercise (quoted by more than 40% of the informants).

Table 2.

Ethnolinguistic analysis of the most quoted wild food plants in Mundimitar/Montemitro (linguistic correspondences are underlined)

| Botanical taxon | Local name (s) in Mundimitar | Folk name (s) in Croatia[48]and Herzegovina (unpublished data) | Folk name (s) in Molise and surrounding South Italian regions[49,50,52,59] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Amaranthus retroflexus |

Pjedruš |

Lodoba, Štir |

Cime de halle, Pricacchione, Pederosse |

|

Apium nodiflorum |

Kanijola |

Celer |

Candele, Cannizzole, Cannole, Lacce selvagge, Sellarina |

|

Asparagus acutifolius |

Sparuga |

Sparožin, Šparoga |

Sparacane, Sparaci, Sparge, Sperne, Spinele |

|

Beta vulgaris |

Blitva |

Bitva divja, Blitva divja, Cikla |

Biete, Biote |

|

Borago officinalis |

Bureina |

Borač, Boražina |

Burracce, Burraina, Verraina |

|

Clematis vitalba |

Škrabut |

Pavina, Pavit, Škrobut |

Vitavale, Vitelle, Vitacchie |

|

Cornus mas |

Kurnja |

Drijen, Drin |

Corniale, Crugnare, Vrignale |

|

Crataegus monogyna/C. oxyacantha |

Glog |

Glog |

Arciprande, Bianghespine, Ciciarille, Spine bianghe |

|

Cynara cardunculus |

Ošnak |

Artičok, Gardun |

Cardone, Carducce, Scalelle |

|

Foeniculum vulgare |

Finoč |

Komorač, Mirodjija, Morač |

Fenucchie |

|

Mercurialis annua |

Mrkulela |

Resulja, Šcerenica |

Mercorella, Murculella |

|

Origanum vulgare |

Pljei |

Metvica, Mravinac, Vranilovka, Vranilova trava |

Arigano, Pnliejo, Regana |

|

Papaver rhoeas |

Mak |

Bologlav, Mak divlji |

Papaina,Papambele, Pupille |

|

Portulaca oleracea |

Prkatj |

Štucliak, Tušani, Tušt |

Perchiacche, Porcacchie, Precacchie |

|

Prunus spinosa |

Ndrnjela |

Brombuli, Crni trn, Trnjina |

Ndrignazze, Prugnele, Spine perugne, Struzzacane |

|

Rosa canina |

Skorčavata |

Srbiguz, Šipak, Šipurak, |

Cacavescie, Raspacule, Scarciacule, Stracciacule |

|

Sinapis spp. |

Sinapa |

Gorušica, Muštarde |

Lassane, Sinape |

|

Sonchus spp. |

Kostriš/ Kašgn |

Kostriš, Ostak, Mličika, Slatčica |

Cascigne, Crespigne, Respigne |

|

Sorbus domestica |

Oskoruša |

Oskoruša |

Ciorve, Scioreve |

|

Tamus communis |

Gljuštre |

Bljušt |

Afine, Curone, Defano |

| Urtica dioica | Kopriva | Bažgava, Kopriva, Žara | Ardiche, Arteche, Strica |

Half of the taxa have correspondence in the Croatian and Herzegovinian folk botanical nomenclature, and the other half with South-Italian folk plant names.

The most quoted species still retain a Slavic name and may have also been used in Dalmatia and Herzegovina before the migration took place. A similar link between linguistic cognates and cultural salience has been shown in a recent food ethnobotanical study conducted among a Greek minority in Calabria [41]. However, this analysis may only express a reasonable probability of the original permanence of plant uses into a new environmental and cultural space, but it cannot be excluded that migrant groups may have acquired new practices of use of previously known plants from the autochthonous population, thus resulting in naming plants with the original language and using them in a very different way from the original one.

On the other hand, the fact that in our case study half of the most salient species – widely available both in Molise and in Dalmatia and Herzegovina-- have South-Italian folk names demonstrates a strong acculturation process that has affected the Slavic community of Montemitro during these last centuries.

We have also compared our findings with all of the previous ethnobotanical data of the Molise Region and of the entire Italian Peninsula. A few uses seem to have been recorded for the first time:

· the culinary use of boiled black bryony (Tamus communis) shoots in sauces and also with pasta;

· the use of squirting cucumber (Ecballium elaterium) juice for treating malaria in humans (in the past);

· the use of aerial parts of the elderberry tree (Sambucus nigra) for treating erysipelas in pigs;

· the use of decoctions of pellitory (Parietaria judaica) for treating haemorrhoids.

Specific ethnobotanical surveys conducted in Dalmatia and Herzegovina are missing in the literature, thus making it very difficult to draft a comprehensive comparison on plant uses. However, a food use of black bryony shoots, which is very common in Mundimitar, seems to be nowadays also common in the Istrian cuisine in Croatia [60] as well in Dalmatia, where it is commonly sold in markets (ŁŁ personal observation, 2012), while in Molise and Abruzzo its food use is considered obsolete.

The wild vegetable mix called mišanca (Zadar-Split) /pazija (Dubrovnik) , sold in every market of the Dalmatian coast (surveyed in March 2012, Łuczaj unpubl.) contains many of the plants used in the study area. For example Sonchus spp., Foeniculum vulgare, Papaver rhoeas, Picris echioides, and to a much lesser extent Eryngium sp. are used as food in Dalmatia nowadays (Table 3). However the existence of this concept of vegetable mix was not recorded in the study area. Strikingly, the data from the study area contain relatively few Asteraceae species, nowadays widely used in Dalmatia under the name radič or žutenica (e.g. Taraxacum spp. , Crepis spp.) and a few other related genera). It must be kept in mind that Dalmatia was under a strong Greek, Roman and Venetian influence, and that the practice of using a variety of wild vegetables in Dalmatia may have a non-Slavic origin. Thus it may be that some of the uses brought by the Slavic emigrants to Italy are actually re-imports of Venetian or Latin customs.

Table 3.

Comparison of the use of wild green vegetables in Mundimitar with the studies from Dalmatia and Hercegovina (the areas where the diaspora of Mundimitar originated)

| Use in the W Balkans | Use in Mundimitar | |

|---|---|---|

|

Amaranthus retroflexus L. (Amaranthaceae) |

G |

x |

|

Apium nodiflorum (L.) Lag. (Apiaceae) |

|

x |

|

Asparagus spp. (mainly Asparagus acutifolius L. ) (Asparagaceae) |

B, G, C, M |

x |

|

Beta vulgaris L. (Amaranthaceae) |

B, G |

x |

|

Borago officinalis L. (Boraginaceae) |

G, S |

x |

|

Bunias erucago L. (Brassicaceae) |

G |

x |

|

Cichorium intybus L. (Asteraceae) |

B, G, S |

x |

|

Clematis vitalba L. (Ranunculaceae) |

G |

x |

|

Cynara cardunculus L. (Asteraceae) |

|

x |

|

Diplotaxis erucoides (L.) DC. (Brassicaceae) |

|

x |

|

Eruca sativa Miller (Brassicaceae) |

B, G |

x |

|

Humulus lupulus L. (Cannabaceae) |

|

x |

|

Mercurialis annua L. (Euphorbiaceae) |

|

x |

|

Papaver rhoeas L. (Papaveraceae) |

G, C, S, L |

x |

|

Picris echioides L. (Asteraceae) |

L |

x |

|

P. hieracioides L. (Asteraceae) |

|

x |

|

Portulaca oleracea L. (Portulacaceae) |

G |

x |

|

Ruscus spp. (Asparagaceae) |

B, G, C |

x |

|

Sinapis alba L and S. arvensis L. (Brassicaceae) |

|

x |

|

Sonchus spp. (Asteraceae) |

B, G, C, S, L |

x |

|

Tamus communis L. (Dioscoreaceae) |

B, G, S, M |

x |

|

Urtica dioica L (Urticaceae) |

S |

x |

|

Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (Apiaceae) |

B, G, C, S, L |

only fruits as seasoning |

|

Allium ampeloprasum L. (Liliaceae) |

B, G, S, L |

|

|

Anchusa arvensis (L.) M. Bieb. (Boraginaceae) |

C |

|

|

Anchusa sp. (Boraginaceae) |

C |

|

|

Arum italicum Mill. (Araceae) |

B |

|

|

Brassica oleracea L. (Brassicaceae) |

G |

|

|

Capsella bursa-pastoris L. (Brassicaceae) |

G |

|

|

Chenopodium urbicum L. (Chenopodiaceae) |

B |

|

|

Cirsium arvense L. (Asteraceae) |

B, G |

|

|

Crepis sp. (Asteraceae) |

C, L |

|

|

Crepis sancta (L.) Babc. (Asteraceae) |

C |

|

|

Crithmum maritimum L. (Apiaceae) |

B, G |

|

|

Daucus carota L. (Apiaceae) |

B, G, S, L |

|

|

Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC. (Brassicaceae) |

B, G |

|

|

Erodium cicutarium (L.) L'Hér. ex Aiton (Geraniaceae) |

C |

|

|

Eryngium maritimum L. and E. campestre L. (Asteraceae) |

B, G |

|

|

Geranium molle L. (Geraniaceae) |

C |

|

|

Hirschfeldia incana (L.) Lagr.-Foss. (Brassicaceae) |

G |

|

|

Hypochoeris radicata L. (Asteraceae) |

G |

|

|

Lactuca perennis L. (Asteraceae) |

B |

|

|

Lactuca serriola L. (Asteraceae) |

S |

|

|

Leontodon tuberosus L. (Asteraceae) |

B |

|

|

Mentha aquatica L. (Lamiaceae) |

B |

|

|

Ornithogalum umbellatum L. (Liliaceae) |

G |

|

|

Reichardia picroides (L.) Roth. (Asteraceae) |

G, S |

|

|

Ranunculus muricatus L. (Ranunculaceae) |

C |

|

|

Rhagadiolus stellatus (L.) Gaertn. (Asteraceae) |

C |

|

|

Rumex spp. (Polygonaceae) |

G, C |

|

|

Salicornia herbacea L. (Amaranthaceae) |

G |

|

|

Silene latifolia Poir. (Caryophyllaceae) |

L |

|

|

Salvia verbenaca L. (Lamiaceae) |

C |

|

|

Silene vulgaris (Mch.) Garcke and related species (Caryophyllaceae) |

B, G |

|

|

Smilax aspera L. (Smilacaceae) |

G |

|

|

Taraxacum megalorrhizon (Forssk.) Hand.-Mazz. (Asteraceae) |

B |

|

|

Taraxacum officinale Weber (Asteraceae) |

B, G, L |

|

|

Tordylium apulum L. (Apiaceae) |

C |

|

|

Tragopogon pratensis L. (Asteraceae) |

B, G, S |

|

|

Urospermum picroides (L.) Desf. (Asteraceae) |

G, C, L |

|

| Urtica pilulifera L. (Urticaceae) | B, G |

B – Bakić and Popović (in this study it is unclear if the data is about eating green parts or underground organs) [56], G – Grlić [57], C – Ćurčić [58], S- Sardelić [59], L – most commonly sold wild greens in Dalmatian markets in 2012 in the form of a vegetable mix (Łuczaj, unpublished); M – sold commonly in Dalmatian markets in 2012 as separate bunches (Łuczaj, unpublished).

It is worth pointing out that nowadays in Dalmatia wild vegetables are mainly boiled, strained and seasoned with olive oil whereas the described uses in the study area often refer to frying, which may be reflective of a more recent acquisition of Italian cooking practices.

The food use of mercury (Mercurialis annua) leaves in soups has instead been recorded only one other time in Italy, in two studies conducted in North-Western Tuscany in the Lucca area [61,62].

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that even within ancient diasporas, as in the Slavic community of Mundimitar, which still exists in Italy after more than five centuries since it was founded, it is possible to find traces of resilience of original TK regarding plants.

A few uses of most quoted plants, which are still named in the original language, may have originated in the migrants’ areas of origin (Dalmatia and Herzegovina).

However, TK is the result of dynamic processes and the case study that we have analysed here also demonstrates a high degree of adaptation, which is shown in both the folk botanical nomenclature (half of the most quoted botanical taxa are named in South-Italian) and in the actual plant folk uses too (very few uses do not correspond with the Italian ethnobotany).

These considerations show that, in contrast with analogous studies conducted on the ethnobotany of recent migrants/newcomer’ groups, TK about plants within ancient diasporas is a very complex, and not well understood, phenomenon.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AdT and AP conceived the study and conducted the field study; AP, ŁŁ, SR, and CLQ performed the data analysis and drafted the discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Alessandro di Tizio, Email: ditizioalessandro@gmail.com.

Łukasz Jakub Łuczaj, Email: lukasz.luczaj@interia.pl.

Cassandra L Quave, Email: cassy.quave@gmail.com.

Sulejman Redžić, Email: redzic0102@yahoo.com.

Andrea Pieroni, Email: a.pieroni@unisg.it.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to all the inhabitants of Mundimitar/Montemitro, for their warm hospitality and for sharing their knowledge with the authors, who collected the data in the field (AdT and AP). We would also like to thank to Prof. Marijana Zovko- Končić for helping in the literature search. This article is dedicated to the unforgettable Dorina Giorgetta, our “key” informant in Mundimitar, who unexpectedly passed away, while we were analysing the findings of the field work.

References

- Leporatti ML, Ivancheva S. Preliminary comparative analysis of medicinal plants used in the traditional medicine of Bulgaria and Italy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;87(2–3):123–142. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Quave CL. Traditional pharmacopoeias and medicines among Albanians and Italians in southern Italy: A comparison. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;101(1–3):258–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Giusti ME, de Pasquale C, Lenzarini C, Censorii E, Gonzales-Tejero MR, Sanchez-Rojas CP, Ramiro-Gutierrez JM, Skoula M, Johnson C. et al. Circum-Mediterranean cultural heritage and medicinal plant uses in traditional animal healthcare: a field survey in eight selected areas within the RUBIA project. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Tejero MR, Casares-Porcel M, Sanchez-Rojas CP, Ramiro-Gutierrez JM, Molero-Mesa J, Pieroni A, Giusti ME, Censorii E, de Pasquale C, Della A. et al. Medicinal plants in the Mediterranean area: synthesis of the results of the project Rubia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116(2):341–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjichambis A, Paraskeva-Hadjichambi D, Della A, Giusti ME, De Pasquale C, Lenzarini C, Censorii E, Gonzales-Tejero MR, Sanchez-Rojas CP, Ramiro-Gutierrez JM. et al. Wild and semi-domesticated food plant consumption in seven circum-Mediterranean areas. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2008;59(5):383–414. doi: 10.1080/09637480701566495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leporatti ML, Ghedira K. Comparative analysis of medicinal plants used in traditional medicine in Italy and Tunisia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukand R, Kalle R. Change in medical plant use in Estonian ethnomedicine: a historical comparison between 1888 and 1994. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135(2):251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj Ł. Changes in the utilization of wild green vegetables in Poland since the 19th century: a comparison of four ethnobotanical surveys. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128(2):395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Muenz H, Akbulut M, Başer KHC, Durmuşkahya C. Traditional phytotherapy and trans-cultural pharmacy among Turkish migrants living in Cologne, Germany. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102(1):69–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Houlihan L, Ansari N, Hussain B, Aslam S. Medicinal perceptions of vegetables traditionally consumed by South-Asian migrants living in Bradford, Northern England. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113(1):100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu DS, Heinrich M. The use of health foods, spices and other botanicals in the sikh community in London. Phytother Res. 2005;19(7):633–642. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yöney A, Prieto JM, Lardos A, Heinrich M. Ethnopharmacy of Turkish-speaking cypriots in greater London. Phytother Res. 2010;24(5):731–740. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceuterick M, Vandebroek I, Torry B, Pieroni A. Cross-cultural adaptation in urban ethnobotany: The Colombian folk pharmacopoeia in London. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120(3):342–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Sheikh QZ, Ali W, Torry B. Traditional medicines used by Pakistani migrants from Mirpur living in Bradford, Northern England. Complement Ther Med. 2008;16(2):81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceuterick M, Vandebroek I, Pieroni A. Resilience of Andean urban ethnobotanies: a comparison of medicinal plant use among Bolivian and Peruvian migrants in the United Kingdom and in their countries of origin. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136(1):27–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Andel T, Westers P. Why Surinamese migrants in the Netherlands continue to use medicinal herbs from their home country. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127(3):694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Gray C. Herbal and food folk medicines of the Russlanddeutschen living in Künzelsau/Taläcker, South-Western Germany. Phytother Res. 2008;22(7):889–901. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Giusti ME. Alpine ethnobotany in Italy: Traditional knowledge of gastronomic and medicinal plants among the Occitans of the upper Varaita valley, Piedmont. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5:32. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramiello Lomagno R, Rovera L, Lomagno PA, Piervittori R. La fitoterapia popolare nella Valle Maira. Annali della Facoltà di Scienze Agrarie dell'Università degli Studi di Torino. 1982;XII:217–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lomagno P, Lomagno Caramiello R. La fitoterapia popolare nella Valle di Susa. Allionia. 1970;16:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Caramiello Lomagno R, Piervittori R, Lomagno PA, Rolando C. Fitoterapia popolare nelle valli Chisone e Germanasca. Nota prima: Valle Germanasca e bassa Val Chisone. Annali della Facoltà di Scienze Agrarie dell'Università degli Studi di Torino. 1984;XIII:259–298. [Google Scholar]

- Pons G. Primo contributo alla flora popolare valdese. Bollettino della Società Botanica Italiana. 1900;101-108:216–222. [Google Scholar]

- Musset D, Dore D. La mauve et l'erba bianca. Une introduction aux enquêtes ethnobotaniques suivie de l'inventaire des plantes utiles dans la vallée de la Stura. Un'introduzione alle indagini etnobotaniche seguita dall'inventario delle piante utili nella Valle della Stura. Mane, France: Musée départemental ethnologique de Haute-Provence, Salagon; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chimenti Signorini R, Fumagalli M. Indagine etnofarmacobotanica nella Valtournanche (Valle d'Aosta) Webbia. 1983;37(1):69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Denarier N. Venti erbe per stare bene. Piante medicinali della Valle d'Aosta. Gressan, Aosta, Italy: Edizioni Vida; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lomagno P, Lomagno Caramiello R. La fitoterapia popolare della Valle del Sangone. Bollettino SIFO. 1977;23:445–452. [Google Scholar]

- Chiovenda-Bensi C. Piante medicinali nell'uso tradizionale della Valle d'Ossola. Atti dell'Accademia Ligure di Scienze e Lettere. 1955;11:32–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chiovenda-Bensi C. Tradizioni e usi fitoterapici popolari. La Valsesia. Atti dell'Accademia Ligure di Scienze e Lettere. 1957;13:190–205. [Google Scholar]

- Remogna M. Metodi tradizionali di cura a Rimella. De Valle Sicida. 1993;4:221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Steiger L, Donini D, Holznecht H, Poppi C. Etnomedicina comparata delle etnie ladine. Studi etno-antropologici e sociologici. 1988;16:37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Poppi C. Medicina popolare in Val di Fassa: relazione di ricerca sul campo. Mondo Ladino. 1989;XIII(3–4):287–326. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A. Altri risultanze sulla medicina popolare in Val di Fassa. Mondo Ladino. 1990;3-4:257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Barbini S, Tarascio M, Sacchetti G, Bruni A. Studio preliminare sulla etnofarmacologia delle comunità ladine dolomitiche. Informatore Botanico Italiano. 1999;31(1–3):181–182. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelletti EM, Trevisan R, Folletto A, Cattolica PM. Le pinate utilizzate in medicina popolare in due vallate trentine: Val di Ledro e Val dei Mocheni. Studi Trentini di Scienze Naturali. 1981;58:119–140. [Google Scholar]

- Zampiva F. Le principali erbe della famacopea cimbra. Cimbri-Tzimbar Vita e cultura delle comunità cimbre. 1998;X(19):135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zampiva F. Róasan (Flora cimbra). I nomi dimenticati di erbe piante e fiori. Verona, Italy: Edizioni Curatorium Cimbricum Veronense; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Giusti ME, Münz H, Lenzarini C, Turković G, Turković A. Ethnobotanical knowledge of the Istro-Romanians of Žejane in Croatia. Fitoterapia. 2003;74(7–8):710–719. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Nebel S, Quave C, Munz H, Heinrich M. Ethnopharmacology of liakra: traditional weedy vegetables of the Arbereshe of the Vulture area in southern Italy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;81(2):165–185. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Quave C, Nebel S, Heinrich M. Ethnopharmacy of the ethnic Albanians (Arbereshe) of northern Basilicata, Italy. Fitoterapia. 2002;73(3):217–241. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(02)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quave CL, Pieroni A. Folk illness and healing in Arbëreshë Albanian and Italian communities of Lucania, Southern Italy. J Folklore Res. 2005;42:57–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nebel S, Pieroni A, Heinrich M. Ta chorta: wild edible greens used in the Graecanic area in Calabria, Southern Italy. Appetite. 2006;47(3):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebel S, Heinrich M. Ta chòrta: A comparative ethnobotanical-linguistic study of wild food plants in a graecanic area in Calabria, Southern Italy. Econ Bot. 2009;63(1):78–92. doi: 10.1007/s12231-008-9069-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxia A, Lancioni MC, Balia AN, Alborghetti R, Pieroni A, Loi MC. Medical ethnobotany of the Tabarkins, a Northern Italian (Ligurian) minority in south-western Sardinia. Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2008;55(6):911–924. doi: 10.1007/s10722-007-9296-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rešetar M. Die serbokroatischen Kolonien Süditaliens. Wien: Alfred Hölder; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- AISEA. Codice Deontologico. http://www.aisea.it.

- Pignatti S. Flora d'Italia. Bologna, Italy: Edagricole; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Committee TFEE. Flora Europaea on CD-ROM. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Šugar I. Hrvatski biljni imenoslov. Nomenclator botanicus Croaticus. Zagreb, Croatia: Matica Hrvatska; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Penzig O. Flora popolare italiana. Raccolta dei nomi dialettali delle principali piante indigene e coltivate in Italia. Genoa, Italy: Orto Botanico della Regia Università; 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Manzi A. Le piante alimentari in Abruzzo. La flora spontanea dell'alimentazione umana. Chieti, Italy: Tinari; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Guarrera PM. Usi e tradizioni della flora italiana. Medicina popolare ed etnobotanica. Rome, Italy: Aracne; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guarrera P, Lucchese F, Medori S. Ethnophytotherapeutical research in the high Molise region (Central-Southern Italy) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motti R, Antignani V, Idolo M. Traditional plant use in the Phlegraean Fields Regional Park (Campania, Southern Italy) Hum Ecol. 2009;37(6):775–782. doi: 10.1007/s10745-009-9254-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menale B, Amato G, Di Prisco C, Muoio R. Traditional uses of plants in North-Western Molise (Central Italy) Delpinoa. 2006;48:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Idolo M, Motti R, Mazzoleni S. Ethnobotanical and phytomedicinal knowledge in a long-history protected area, the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park (Italian Apennines) J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127(2):379–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakić J, Popović M. Nekonvencionalni izvori u ishrani na otocima i priobalju u toku NOR-a. Izd Mornaričkog glasnika. 1983. pp. 49–55.

- Grlić L. Enciklopedija samoniklog jestivog bilja. Rijeka, Croatia: Ex Libris; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ćurčić V. Narodne ribarstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini. Part 2. Glasnik Zemaljskog Muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini. 1913;25:421–514. [Google Scholar]

- Sardelić S. Samoniklo jestivo bilje – mišanca, gruda, parapač. Etnološka istraživanja. 2008;1(12/13):387–396. [Google Scholar]

- Istrianet.org. Fritade - Fritaje - Omelets. Ostaria Istriana. http://www.istrianet.org/istria/gastronomy/osteria/fritade.htm.

- Tomei PE, Lippi A, Uncini Manganelli RE. L’uso delle specie vegetali spontanee nella preparazione delle zuppe di magro in Lucchesia (LU) Funghi, tartufi ed erbe mangerecce: 1995; L'Aquila, Italy. 1995. pp. 243–248.

- Camangi F, Stefani A. Le tradizioni phytoalimurgiche in Toscana: le piante selvatiche nella preparazione delle zuppe. Rivista di Preistoria, Etnografia e Storia naturale, Istituto Storico Lucchese. 2004;2(1):7–17. [Google Scholar]