A systematic review of qualitative studies conducted by Frances Bunn and colleagues identifies and describes the experiences of patients and caregivers on receiving and adapting to a diagnosis of dementia.

Abstract

Background

Early diagnosis and intervention for people with dementia is increasingly considered a priority, but practitioners are concerned with the effects of earlier diagnosis and interventions on patients and caregivers. This systematic review evaluates the qualitative evidence about how people accommodate and adapt to the diagnosis of dementia and its immediate consequences, to guide practice.

Methods and Findings

We systematically reviewed qualitative studies exploring experiences of community-dwelling individuals with dementia, and their carers, around diagnosis and the transition to becoming a person with dementia. We searched PubMed, PsychINFO, Embase, CINAHL, and the British Nursing Index (all searched in May 2010 with no date restrictions; PubMed search updated in February 2012), checked reference lists, and undertook citation searches in PubMed and Google Scholar (ongoing to September 2011). We used thematic synthesis to identify key themes, commonalities, barriers to earlier diagnosis, and support identified as helpful. We identified 126 papers reporting 102 studies including a total of 3,095 participants. Three overarching themes emerged from our analysis: (1) pathways through diagnosis, including its impact on identity, roles, and relationships; (2) resolving conflicts to accommodate a diagnosis, including the acceptability of support, focusing on the present or the future, and the use or avoidance of knowledge; and (3) strategies and support to minimise the impact of dementia. Consistent barriers to diagnosis include stigma, normalisation of symptoms, and lack of knowledge. Studies report a lack of specialist support particularly post-diagnosis.

Conclusions

There is an extensive body of qualitative literature on the experiences of community-dwelling individuals with dementia on receiving and adapting to a diagnosis of dementia. We present a thematic analysis that could be useful to professionals working with people with dementia. We suggest that research emphasis should shift towards the development and evaluation of interventions, particularly those providing support after diagnosis.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary.

Editors' Summary

Background

Dementia is a decline in mental ability severe enough to interfere with daily life. Alzheimer disease is the most common type of dementia. People with dementia usually have problems with two or more cognitive functions—thinking, language, memory, understanding, and judgment. Dementia is rare before the age of 65, but about a quarter of people over 85 have dementia. Because more people live longer these days, the number of patients with dementia is increasing. It is estimated that today between 40 and 50 million people live with dementia worldwide. By 2050, this number is expected to triple.

One way to study what dementia means to patients and their carers (most often spouses or other family members) is through qualitative research. Qualitative research aims to develop an in-depth understanding of individuals' experiences and behavior, as well as the reasons for their feelings and actions. In qualitative studies, researchers interview patients, their families, and doctors. When the studies are published, they usually contain direct quotations from interviews as well as summaries by the scientists who designed the interviews and analyzed the responses.

Why Was This Study Done?

This study was done to better understand the experiences and attitudes of patients and their carers surrounding dementia diagnosis. It focused on patients who lived and were cared for within the community (as opposed to people living in senior care facilities or other institutions). Most cases of dementia are progressive, meaning symptoms get worse over time. Diagnosis often happens at an advanced stage of the disease, and some patients never receive a formal diagnosis. This could have many possible reasons, including unawareness or denial of symptoms by patients and people close to them. The study was also trying to understand barriers to early diagnosis and what type of support is useful for newly diagnosed patients and carers.

What Did the Researchers Do and Find?

The researchers conducted a systematic search for published qualitative research studies that reported on the experience, beliefs, feelings, and attitudes surrounding dementia diagnosis. They identified and reviewed 102 such studies. Among the quotations and summaries of the individual studies, they looked for prominent and recurring themes. They also compared and contrasted the respective experiences of patients and carers.

Overall, they found that the complexity and variety of responses to a diagnosis of dementia means that making the diagnosis and conveying it to patients and carers is challenging. Negative connotations associated with dementia, inconsistent symptoms, and not knowing enough about the signs and symptoms were commonly reported barriers to early dementia diagnosis. It was often the carer who initiated the search for help from a doctor, and among patients, willingness and readiness to receive a diagnosis varied. Being told one had dementia had a big impact on a patient's identity and often caused feelings of loss, anger, fear, and frustration. Spouses had to adjust to increasingly unequal relationships and the transition to a role as carer. The strain associated with this often caused health problems in the carers as well. On the other hand, studies examining the experience of couples often reported that they found ways to continue working together as a team.

Adjusting to a dementia diagnosis is a complex process. Initially, most patients and carers experienced conflicts, for example, between autonomy and safety, between recognizing the need for help but reluctance to accept it, or between living in the present and dealing with anxiety about and preparing for the future. As these were resolved and as the disease progressed, the attitudes of patients and carers towards dementia often became more balanced and accepting. Many patients and their families adopted strategies to cope with the impact of dementia on their lives in order to manage the disease and maintain some sort of normal life. These included practical strategies involving reminders, social strategies such as relying on family support, and emotional strategies such as using humor. At some point many patients and carers reported that they were able to adopt positive mindsets and incorporate dementia in their lives.

The studies also pointed to an urgent need for support from outside the family, both right after diagnosis and subsequently. General practitioners and family physicians have important roles in helping patients and carers to get access to information, social and psychological support, and community care. The need for information was reported to be ongoing and varied, and meeting it required a variety of sources and formats. Key needs for patients and carers mentioned in the studies include information on financial aids and entitlements early on, and continued access to supportive professionals and specialists.

What Do These Findings Mean?

Qualitative studies to date on how patients and carers respond to a diagnosis of dementia provide a fairly detailed picture of their experiences. The summary provided here should help professionals to understand better the challenges patients and carers face around the time of diagnosis as well as their immediate and evolving needs. The results also suggest that future research should focus on the development and evaluation of ways to meet those needs.

Additional Information

Please access these websites via the online version of this summary at http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001331.

Wikipedia has pages on dementia and qualitative research (note that Wikipedia is a free online encyclopedia that anyone can edit)

Alzheimer Europe, an umbrella organization of 34 Alzheimer associations from 30 countries across Europe, has a page on the different approaches to research

The UK Department of Health has pages on dementia, including guidelines for carers of people with dementia

MedlinePlus also has information about dementia

Introduction

Dementia affects one in 20 people over the age of 65 and one in five over the age of 80. World-wide there are an estimated 35.6 million people with dementia. By 2050 this number will rise to over 115 million [1]. In 2010 the total estimated worldwide costs of dementia were US$604 billion, with 70% of the costs occurring in western Europe and North America [2]. There is evidence that many patients who meet the criteria for dementia never receive a formal diagnosis [3]–[6] or receive a diagnosis only late in the disease trajectory [7]. There remains wide variability in current practice and attitudes to diagnostic disclosure [8], with some professionals worried about the possible harm of early diagnosis of a condition widely seen as untreatable and life-changing [9]. There is, however, growing support for early diagnosis [10]–[12], as it may improve quality of life for patients and carers, delay or prevent care home admissions [13],[14], and facilitate referral to specialist services and treatment [11],[15].

There is increasing recognition of the importance of systematically reviewing qualitative research [16], as it allows the development of in-depth understanding of persistent themes, explores transferability, and prevents unnecessary duplication of research. Previous reviews have looked at patient and carer experiences of dementia [17],[18] and disclosure of diagnosis [8],[19],[20], but none, to our knowledge, has performed a comprehensive thematic synthesis of qualitative studies exploring the experiences of people with dementia and their family members of receiving and adapting to a diagnosis, and of service delivery. Our aim was to inform the debate about early diagnosis and service provision by systematically reviewing qualitative literature on the psychosocial factors that shape patient and carer experiences of diagnosis and early treatment. We aimed to identify the following: key themes, commonalities, and differences across groups; barriers to early diagnosis; and which support services individuals newly diagnosed with dementia and their carers perceive as helpful.

Methods

Selection Criteria

We included qualitative studies that explored patient and carer experiences around diagnosis and treatment of dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI). This included studies from any established qualitative tradition and using any recognised qualitative methodology. Mixed method studies were included if they had a qualitative element, but only the qualitative data were used in the analysis. The main outcomes of interest were patient and carer attitudes, beliefs, and feelings around becoming or caring for an individual with dementia. In particular we searched for data on responses to early signs of dementia, receiving and adapting to a diagnosis, and experiences of post-diagnosis support. We focused on community-dwelling participants and excluded studies in long-term care settings or published in languages other than English. The reporting of the review follows PRISMA guidance (Text S1), and the methods for the review were pre-specified in a protocol (Text S2).

Search Strategy

We searched for all potentially relevant published and unpublished literature, with no date restrictions, and regardless of country of origin. Studies were identified by computerised searches of PubMed (1950–2012), PsychINFO (Ovid) (1806–2010), Embase (Ovid) (1980–2010), CINAHL (EBSCO Publishing) (1980–2010), and the British Nursing Index (NHS Evidence) (1985–2010). An example search query is given in Box 1. In addition, we employed extensive lateral search techniques (ongoing March 2010–September 2011), such as checking reference lists, performing key word searches in Google Scholar, contacting experts, and using the “cited by” option in Google Scholar and the “related articles” option in PubMed. Such lateral search strategies have been shown to be particularly important for identifying non-randomised studies [21]. The original electronic database searches were conducted between March and May 2010, with the PubMed search updated in February 2012.

Box 1. Example Search Query

The following search query was used for the PubMed searches* (May 2010, updated February 2012):

(disability OR disablement OR aware OR awareness OR self OR fear OR emotions OR “self concept” OR self assessment OR “self care” OR adaptation OR stress OR autonomy OR denial OR sick role OR coping OR cope OR patient participation OR self disclosure OR life [ti] OR live [ti] or living [ti]) AND (confusion OR memory loss OR “early dementia” OR “mild dementia” OR “moderate dementia” OR alzheimers OR mild cognitive disorder OR (MCI (cognition disorder AND (mild OR moderate OR early)))) AND (caregivers OR social support OR self-help groups OR relatives OR carers OR health care staff OR spouses OR dyadic OR partner OR communication OR nursing)

*Search terms were adapted for other databases.

Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts identified by the electronic search, applied the selection criteria to potentially relevant papers, and extracted data using a standardised checklist. Where results of a study were reported in more than one publication, we grouped reports together and marked the publication with the most complete data as the primary reference; the other papers describing the same study were classified as associated papers. We collected data on study design (including theoretical framework), aims, methods, participant characteristics, areas covered (e.g., symptom recognition, receiving a diagnosis, adjusting to a diagnosis, and issues relating to service delivery), and common themes.

Two reviewers independently assessed study quality using a checklist based on Spencer et al.'s framework for assessing quality in qualitative research [22]. This framework has been adapted by one of the authors and used in previous work [23],[24]. In addition, the overall reliability and usefulness of the study to the research questions was graded as low, medium, or high. Reliability related to the quality of the study, and usefulness to the relevancy of a paper in the context of our review. The core quality assessment principles are summarised in Table 1. Data compiled by the two reviewers were compared for agreement, and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion or by consultation with a third researcher. As there is no consensus or empirically tested method for excluding qualitative studies from reviews on the basis of quality, we included all studies regardless of their quality.

Table 1. Core principles of study quality assessment.

| Quality Criterion | Further Details |

| Scope and purpose | E.g., clearly stated question, clear outline of theoretical framework |

| Design | E.g., discussion of why particular approach/methods chosen |

| Sample | E.g., adequate description of sample used and how sample was identified and recruited |

| Data collection | E.g., systematic documentation of tools/guides/researcher role, recording methods explicit |

| Analysis | E.g., documentation of analytic tools/methods used, evidence of rigorous/systematic analysis |

| Reliability and validity | E.g., presentation of original data, how categories/concepts/themes were developed and were they checked by more than one author, interpretation, how theories developed, triangulation with other sources |

| Generalisability | E.g., sufficient evidence for generalisability or limits made clear by author |

| Credibility/integrity/plausibility | E.g., provides evidence that resonates with other knowledge, results/conclusions supported by evidence |

| Overall weight for reliability/trustworthiness | Low = one or more “not at all” values for the first five criteria above, medium = at least 4/5 of the first five criteria above marked as “fully or mostly”, high = all of the first five criteria above marked “fully or mostly” and none marked “not at all” |

| Overall weight for usefulness of findings for review | Considers the following: (i) to what extent does the study help us to understand one or more of the topics covered in the review? (ii) how rich are the findings? (iii) has the study successfully enhanced our understanding of a new area/sample or enriched an old one? |

Analysis

We synthesised our study findings using thematic analysis. This process, which involves identifying prominent or recurring themes, has previously been used to successfully synthesise a large number of studies [25], and draws on existing literature around the synthesis of qualitative research [26]–[29]. Defining what counts as “data” in qualitative research is not straightforward [29]. We took the approach suggested by Thomas and Harden [29] and took “data” to be not just that in the form of quotations but all of the text labelled as “results” or “findings” in study reports.

Studies judged to have met the inclusion criteria were independently reviewed and coded by two reviewers by hand. They applied open codes to text, identified themes, and documented supporting evidence in the form of quotes. From this, a list of initial codes and themes was created. These codes were then inserted into qualitative analysis software (NVivo), and PDFs of all included studies were imported for further analysis. The use of such software can facilitate the development of themes and allow reviewers to examine the contribution made to their findings by individual studies or groups of studies [29]. Analysis in NVivo involved examination of concepts for similarities and differences, refinement of descriptive themes, verification that data was a “good fit” for the themes, and development of analytic themes. We then undertook a final process of verification using the 28 studies that had scored high for both reliability and usefulness.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required for this work.

Results

Description of Studies

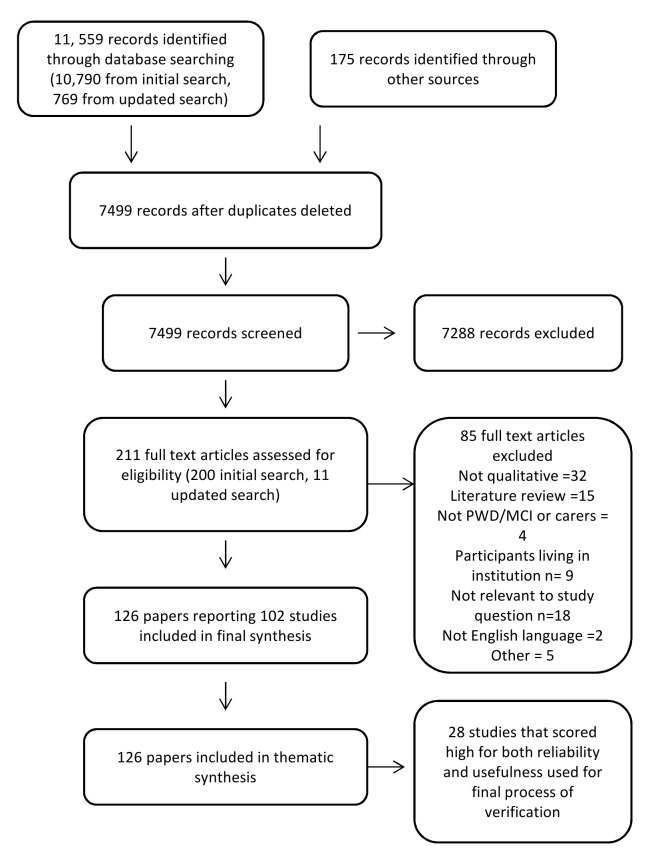

In all, 126 papers met our inclusion criteria. Of those, 102 were classified as primary studies [30]–[131], and a further 24 as associated papers [132]–[155]. The links between primary and associated papers can be seen in Table S1. An overview of the selection process can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow chart of study selection process.

PWD, person with dementia.

Studies included a total of 3,095 participants: 1,145 individuals with dementia or MCI and 1,950 informal carers. We found studies conducted in 14 different countries, although the majority (76%) were from the UK or North America. Study characteristics are summarised in Table 2, with details of individual studies provided in Table S1. Participants were community-dwelling, the majority lived with a carer, and they were predominantly white. However, 16 studies [32],[42],[66],[67],[70],[72],[74],[85],[86],[88],[92],[98]–[100],[118],[122] either focused on the views and experiences of black and minority ethnic groups in the UK and North America or compared the views of different ethnic groups.

Table 2. Overview of study characteristics.

| Study Information | Study Methods | Type of Participants |

| Year of publication | Data collection methods | Participants |

| Range 1989–2011, half published from 2005 onwards | Some used more than one approach | PWD n = 61 |

| Country | Most common methods: interviews n = 93, focus groups n = 18 | Person with MCI n = 13 |

| UK n = 41 | Methodological approach | Informal carers of PWD/person with MCI n = 72 |

| US n = 27 | Phenomenological n = 29 | Age |

| US and UK n = 2 | Ethnographic n = 5 | Range 40–97 y, but majority over 70 y |

| Europe (excluding UK) n = 16 | Grounded theory n = 27 | Of 35 studies that gave mean/median age, majority had mean age in the 70 s |

| Canada n = 11 | Other n = 8 (e.g., biographical approach, case study) | Ethnicity |

| Rest: Australia (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), and Asia (n = 3) | Not specified n = 33 | Not specified n = 41 |

| Subject areas covered in study a | Recruitment | White participants only n = 27 |

| Symptom recognition n = 32 | Most commonly recruited from: memory clinics n = 38, voluntary organisations n = 23 | Asian participants only n = 7 |

| Receiving diagnosis n = 37 | Sample | Black participants only n = 1 |

| Adjusting to diagnosis/condition n = 78 (includes PWD and carer perspective) | Convenience sample n = 35 | Mixture of ethnic backgrounds n = 26 |

| Service delivery n = 25 | Purposive or theoretical sample n = 63 | Received a diagnosis |

| Setting | Not clear n = 4 | Yes n = 74 |

| Community-dwelling | Number of data collection points | No n = 4 |

| Living with family member n = 46 | One n = 73 | Rest mixture or not clear |

| In other studies, the majority lived with family member (most commonly a spouse) | Two n = 10 | Stage of dementia |

| More than two n = 13 | 26 studies reported MMSE or similar, all but two mild/moderate | |

| Different for different participants n = 6 | Type of dementia | |

| Not specified n = 42 | ||

| Where it was reported most common type was Alzheimer disease n = 53, early onset n = 3 |

Sample sizes refer to the numbers of studies, not the number of individual participants.

Studies sometimes classified as more than one category.

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; PWD, person with dementia.

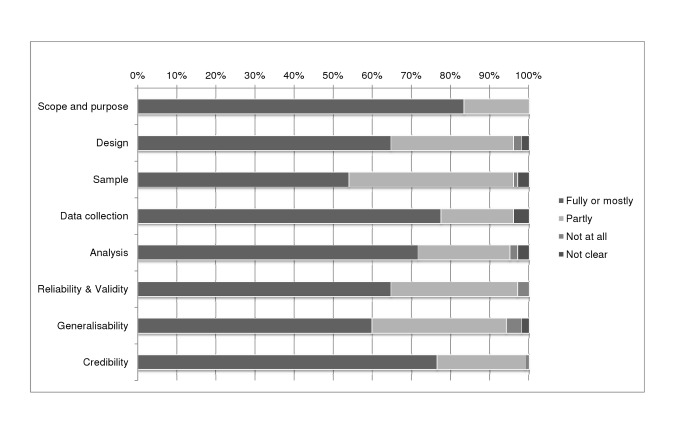

Study Quality

Overall, 32% of the studies scored high for reliability, 32% medium, and 35% low, and 57% scored high, 30% medium, and 13% low for usefulness; 27% scored high for both reliability and usefulness. A summary of individual quality assessment scores can be found in Table S1 and of overall quality assessment domains in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Summary of quality assessment domains.

This figure shows review authors' judgements about each quality domain presented as percentages across all included studies.

Findings from the Thematic Analysis

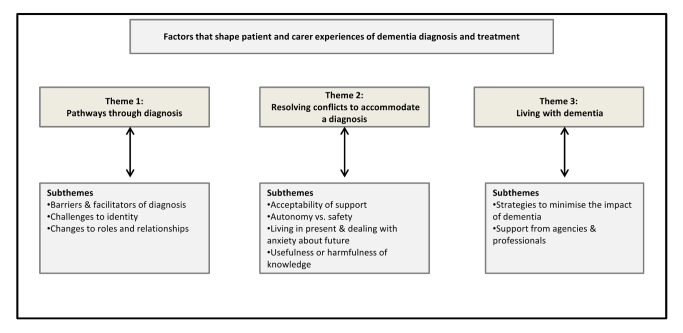

We identified three overarching thematic categories as being central to the process of receiving and adapting to a diagnosis of dementia: (1) pathways through diagnosis (including barriers and facilitators of earlier diagnosis, and the challenge of the diagnosis to identity, roles, and relationships); (2) conflicts that need to be resolved to accommodate the diagnosis (including the acceptability or otherwise of support, autonomy versus safety, the need to focus on today or tomorrow, and the usefulness or harmfulness of knowledge); and (3) living with dementia (including practical strategies to minimise the impact of dementia, and the support that professionals and agencies can give) (see Figure 3). The evidence to support these themes can be seen in Table S2.

Figure 3. Themes and subthemes.

This figure shows the three overarching themes and the related subthemes that emerged from our analysis.

The themes apply both to the individuals with dementia and to their family carer/s, and are not necessarily sequential but are interlinked and reflect ongoing processes of adjustment that can occur from the moment symptoms of dementia appear. Quotes supporting each theme are presented in Table S3. Each thematic category is discussed in more detail below. Supporting citations in the text are representative rather than comprehensive.

Theme 1: Pathways through Diagnosis

Barriers to early diagnosis

Among our sample, persistent barriers to early diagnosis were stigma, the normalisation of symptoms, and a lack of awareness about the signs and symptoms of dementia. It often took a trigger event or tipping point such as a hospitalisation or bereavement [34],[37],[40],[42],[51],[53],[92],[114],[118],[138] before people sought help. Family members often recognised something was wrong before the person with dementia did, and were frequently instrumental in obtaining a diagnosis [32],[40],[41],[45],[54],[72],[88],[115],[129]. There was evidence of greater stigma among minority ethnic populations and evidence that they were less likely to recognise symptoms of dementia as an illness than white individuals, and more likely to ascribe these symptoms to the ageing process [32],[86],[118],[119]. In addition, symptoms of dementia were sometimes given cultural or religious explanations [118]. As many studies did not provide detailed demographic information, it was unclear whether level of education or socioeconomic status impacted on awareness of dementia and help-seeking behaviour. Studies suggest that in some cases doctors are slow to recognise symptoms or reluctant to give a diagnosis [38],[39],[68],[74],[88],[92],[124], and that even when people have been referred to memory services the process may be slow, with long periods of waiting [93],[152].

Impact of diagnosis

Regardless of culture and context, we found many similarities in individual's experiences of becoming a person with dementia. Dementia had an enormous impact on identity [72],[91],[121], leading to feelings of loss, anger, uncertainty, and frustration. [33],[37],[50],[53],[58]–[61],[77],[79],[109]. People with dementia struggled to preserve aspects of their former self and were often supported in this by family carers, who focused on remaining abilities rather than drawing attention to mistakes [109],[144]. Dementia also had a significant impact on roles and relationships, both within the family and in wider social networks. A desire to preserve a pre-dementia identity sometimes led to people being reluctant to disclose their diagnosis to family or wider social networks [52],[53],[109], which could lead to social isolation [53],[62],[105]. Despite this, some studies suggested that eventually both the individuals with dementia and their carers reached a state of acceptance [36],[45],[88],[91].

Unsurprisingly, our analysis revealed that dementia had a significant impact on both the individuals with dementia and their families. Spouses had to adjust to increasingly unequal relationships [30],[54],[63],[64],[97],[104],[114],[123],[125], and communication between the couple was often affected. However, studies looking at the experiences of couples often found an emphasis on working together as a team, with a high degree of mutuality [39],[50],[88],[91],[110],[134]. It was clear that there was often significant strain on carers [39],[42],[44],[56],[109],[119],[123],[127], which often impacted adversely on their own health [43],[44],[61],[78],[117].

For some individuals, receiving a diagnosis was the beginning of the adjustment process, but for others, who had been experiencing symptoms for some time, considerable adjustment had already preceded the diagnosis. Although diagnosis was often traumatic [38],[50],[51],[62],[152], the validation of suspicions could come as a relief [45],[93],[129]. There was also a proportion of individuals with dementia and carers who continued to consider memory loss insignificant even after diagnosis [51],[93],[119].

Theme 2: Resolving Conflicts to Accommodate a Diagnosis

Among our sample, beliefs about, and perceptions of, dementia varied considerably, with meanings attached to a diagnosis being shaped by the individual's current situation, by past experiences, and by exposure to others with dementia. For example, families that included a member with professional experience of dementia or who had a relative with dementia were more likely to completely acknowledge a diagnosis than those who had had no previous exposure to dementia [84]. Adjusting to a diagnosis is a complex process, and a number of ambiguities and polarised findings emerged from our analysis (see Box 2). These ambiguities represent conflicts that may need to be resolved in order to accommodate a diagnosis.

Box 2. Polarised Findings

Reactions to, and readiness for, a diagnosis may vary between individuals and between the individuals with dementia and their family/carers.

Individuals with dementia and their families/carers may struggle to preserve a pre-dementia identity whilst also adapting to a diagnosis and assimilating the disease into a new identity.

Carers may be torn between protecting the person with dementia and promoting their independence.

Individuals with dementia and their carers may focus on the present whilst also experiencing anxiety about the future.

There can be a tension between a desire to maintain social contacts and strategies to minimise or normalise the impact of dementia.

Information may be empowering for some people, but others may reject new knowledge and resist a diagnosis.

Peer support is often beneficial but can have a negative impact by showing what the future may hold.

Studies identified the potential conflict that could arise as people strove to preserve identity and autonomy in the face of increasing symptoms. This sometimes led to an apparent unawareness of or a resistance to acknowledge a diagnosis [37]. Study authors did not, however, interpret this simply as denial but rather as a self-maintaining strategy [136] or a deliberate choice to be seen as an agent rather than an object [90]. This was reflected in individual's attitudes towards information, and there was evidence that some people with dementia and their carers actively sought information [89],[90], whereas others rejected new knowledge. However, understanding of, and attitudes towards, dementia were not fixed, and evolved throughout the disease trajectory.

Theme 3: Living with Dementia

This theme relates to the strategies that individuals with dementia and their families adopted to deal with the impact of dementia on their lives, and also to the support they required from professionals and agencies. The adoption of strategies to manage the disease, minimise losses, reduce social isolation, and maintain normalcy was common [50],[58],[69],[90],[134]. This included practical strategies such as using reminders or prompts, social strategies such as relying on family support, and emotional strategies such as using humour or finding meaningful activity.

Supporting People with Dementia and Their Carers

The general practitioner or family physician was generally the first point of contact for people with dementia and their carers [43],[93] and had an important role to play in facilitating service access [43],[74]. However, in our sample, experiences were mixed, with some participants reporting a delay in referral to memory services and others reporting confidentiality obstacles, with doctors reluctant to talk to carers about their family member with dementia [74],[88],[106],[124]. Attending memory clinics could be shocking or frightening [51],[75],[94], and receiving a diagnosis could lead to increased tension as someone negotiated a new identity as a person with dementia [37].

There was a clear need for greater support after diagnosis [78], including advice [61],[129], social and psychological support [61],[125], access to community care [43],[93], and respite [127]. There was evidence that valuable support was provided by voluntary organisations such as the Alzheimer's Society [93],[106],[114], although signposting to these needed to be improved [61]. Information provision was seen as key in many studies, but it was clear that better knowledge sharing at point of diagnosis was not always the solution [152]. The information needs of patients varied over time, and information provision needed to be ongoing, with flexibility in timing and format [93],[106].

Amongst people with Alzheimer disease and their family carers, there was variation in perceptions of the benefits of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, with some studies reporting that medication gave people hope [48],[71],[97],[111],[121],[152], one study reporting that patients and their carers felt that the benefits were not clear but they were “worth a try” [71], and two studies reporting that patients felt medication had little to offer them [62],[106]. Studies suggested that there was now an increasing expectation that medication would be available [93], that attitudes towards medication got less positive over time [49], and that drug treatment was often initiated by the carer [71].

Amongst our sample it was clear that many people found peer support valuable [37],[38],[72],[93],[129],[131]. However, for others there could be negative consequences, as the inclusion of people at different stages in the dementia trajectory could make people aware of what the future held for them [37]. The timing of referral to community-based support groups may be key [43],[78],[106], and such decisions are likely to be facilitated by continuous therapeutic relationships between individuals with dementia and the practitioners involved in their care.

Discussion

We found 102 studies exploring the experiences of community-dwelling individuals with dementia or MCI, and their family carers, of diagnosis, treatment, and the transition to becoming a person with dementia. What emerged from our analysis was the complexity and variety of responses to becoming a person with dementia, and how this makes diagnosing and supporting this group particularly challenging. There were many commonalities, but beliefs and experiences were context-specific and could be polarised. For example, willingness or readiness to receive a diagnosis varied, and there was evidence that it was often a carer rather than the person with memory problems who initiated a diagnosis. Carers were also often torn between protecting the person with dementia and promoting his or her independence. Moreover, it was clear that individuals with dementia and their family and friends were simultaneously struggling to preserve a pre-dementia self whilst at the same time accommodating the diagnosis and assimilating the disease into a new identity.

We used systematic and rigorous methods for reviewing qualitative literature. However, there are a number of methodological issues that could affect the validity of our findings. Qualitative studies are challenging to identify using standard search techniques [156],[157], and despite our efforts to identify all available studies, we cannot exclude the possibility that some were missed. Moreover, excluding studies reported in languages other than English may have introduced bias. However, we used a comprehensive search strategy, including extensive lateral searching to minimise missing studies, we included studies from 14 different countries, and we are confident that we have reached thematic saturation.

We did not exclude studies from our review on the basis of quality, but we did attempt to “weight” studies by using only those that scored high for both reliability and usefulness in a final process of verification of our themes. However, this approach may be contentious, as there is no consensus on what constitutes a “good” quality qualitative study, nor well-established methods for weighting qualitative studies [22],[158]. That said, our quality assessment procedures were thorough, and the process of reaching inter-reviewer agreement maximised robustness.

Although not all studies provided demographic information, analysis of the characteristics of participants in the studies included in the systematic review suggested that there was a skew towards more affluent, educated participants, most of whom were white. Whilst qualitative research does not generally set out to be representative, it is appropriate to consider the transferability of findings. It is, therefore, a concern that much of the research in this area has been carried out on those populations more easily accessible to researchers. Such populations may have different attitudes to information provision and be more accustomed to self-advocacy [37]. Moreover, although more than 40% of studies did not specify what type of dementia participants had, where this information was given, it was clear that the majority had Alzheimer disease. The experiences of individuals with Alzheimer disease and their carers may not be directly transferable to people with other types of dementia.

The themes in the review relating to coping strategies, the impact of dementia on quality of life and relationships, and experiences of care were similar to those from other reviews [17],[18]. It has been suggested that dementia is not necessarily a source of dreadful suffering [18],[19], and, indeed, among our sample we found evidence that many people adopted positive mindsets and appeared to successfully incorporate dementia into their lives. Nevertheless, it was clear that dementia has a significant impact on people's lives and relationships and is a major threat to identity. Moreover, the progressive nature of the disease means that the process is cyclical and requires constant adjustment. This review highlights how priorities and views change over time, and the need for services to be organised to address that process. Previous reviews [8],[19] have found that people with dementia and their carers are generally in favour of disclosure, and this is supported by this review. However, it is clear that a tension exists between the self-maintaining strategies people employ to minimise the impact of dementia on their lives and sense of self, and the acceptance of a diagnosis and all its implications [136].

Implications for Practice

Our review suggests that key needs for people with dementia and their carers include the early provision of information about financial aids and entitlements, the opportunity to talk to supportive professionals, signposting to appropriate statutory and voluntary services, and specialist support. Support needs to be ongoing, flexible, and sensitive to the needs of different groups, such as those with early onset dementia [38] or minority ethnic groups [118]; it needs to take into account the needs for continuity of care [33]; and it needs to manage care needs and safety whilst being aware of the person's sense of identity and dignity [125]. In the UK it has been suggested that specialist dementia advisors might provide such support [159]. Indeed, it is clear from the literature that the needs of people with dementia and their carers are complex and varied, and those making decisions about the timing and delivery of services need appropriate expertise and training. A further consideration relates to the availability of appropriate resources. It is possible that publicity around early diagnosis, such as the UK government campaign to raise public awareness of the early signs of dementia, may be raising expectations of services in the earlier stages of the illness [93]. This has implications for service delivery, as it may lead to the diversion of resources away from those with more advanced dementia.

Implications for Research

This review provides a comprehensive account of studies reporting the experiences of community-dwelling individuals with dementia and their carers on receiving a diagnosis and becoming a person with dementia. Indeed, there is now a substantial body of qualitative research on the transition to becoming a person with dementia. However, such research has largely been carried out in community-based populations that are easily accessible to researchers. Less is known about the oldest old, those who do not access services, or those have comorbid health conditions. Our review excluded individuals living in long-term care, and further research may be needed to explore issues around diagnosis for people living in residential homes. Although we included experiences of post-diagnosis support and treatment, the focus of our review was on the earlier stages of dementia, and we did not address issues such as behavioural problems or the transition to long-term care. Furthermore, many studies provided little or no demographic data, and it was difficult to assess the impact of factors such as type of dementia, level of education, or other socioeconomic factors on patient and carer experiences. Future qualitative studies should consider including greater detail about the characteristics of participants so that transferability can be better assessed.

Conclusions

It is often suggested that the voice of the person with dementia is not present in research. We found this not to be the case in qualitative research studies. There is now a substantial body of qualitative evidence relating to the experiences of community-dwelling individuals with cognitive impairment and their family carers, particularly in relation to the transition to becoming a person with dementia. This review provides a comprehensive account of how people accommodate and adapt to a diagnosis of dementia that could be useful to professionals working with individuals with dementia. The synthesis focuses attention on three aspects of the diagnostic transition: the challenge the diagnosis poses to identity and role, the conflicts that may need to be resolved to accommodate the diagnosis, and the practical management strategies that can assist individuals with dementia and their families. The next steps to ensure patient benefit should involve the development and evaluation of interventions, particularly those relating to post-diagnosis support.

Supporting Information

PRISMA checklist.

(DOC)

Protocol for the review.

(DOC)

Characteristics of included studies.

(DOCX)

Themes and supporting evidence. This table shows the themes that arose from our analysis and the evidence to support them.

(DOCX)

Examples of quotations illustrating themes and author interpretations of findings. This table provides examples of quotes supporting the themes from our analysis and gives examples of the ways authors of our included studies interpreted their findings.

(DOCX)

Abbreviations

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

Funding Statement

This article presents independent research commissioned by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under Research for Patient Benefit (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-0808-16024). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, nor the Department of Health. The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

References

- 1.Alzheimer's Disease International (2009) World alzheimer report 2009. London: Alzheimer's Disease International. Available: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/files/WorldAlzheimerReport.pdf. Accessed 18 September 2012.

- 2.Alzheimer's Disease International (2010) World alzheimer report 2010: the global economic impact of dementia. London: Alzheimer's Disease International. Available: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/files/WorldAlzheimerReport2010.pdf. Accessed 18 September 2012.

- 3. Iliffe S, Booroff A, Gallivan S, Goldenberg E, Morgan P, et al. (1990) Screening for cognitive impairment in the elderly using the mini-mental state examination. Br J Gen Pract 40: 277–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, Harris R, Lohr KN (2003) Screening for dementia in primary care: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 138: 927–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banerjee S, Chan J (2008) Organisation of old age psychiatric services. Psychiatry 7: 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.UK National Audit Office (2010) Improving dementia services in England—an interim report. London: UK National Audit Office.

- 7. Rait G, Walters K, Bottomley C, Petersen I, Iliffe S, et al. (2010) Survival of people with clinical diagnosis of dementia in primary care: cohort study. BMJ 341: c3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bamford C, Lamont S, Eccles M, Robinson L, May C, et al. (2004) Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 19: 151–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iliffe S, Manthorpe J, Eden A (2003) Sooner or later? Issues in the early diagnosis of dementia in general practice: a qualitative study. Fam Pract 20: 376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Social Care Institute for Excellence (2006) Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers. NICE clinical guidance 42. Available: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG042NICEGuideline.pdf. Accessed 26 August 2012.

- 11.UK National Audit Office (2007) Improving services and support for people with dementia. London: UK National Audit Office.

- 12.UK Department of Health (2010) Quality outcomes for people with dementia: building on the work of the national dementia strategy. London: UK Department of Health.

- 13. Banerjee S, Willis R, Matthews D, Contell F, Chan J, et al. (2007) Improving the quality of care for mild to moderate dementia: an evaluation of the Croydon Memory Service Model. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22: 782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mittelman MS, Roth DL, Clay OJ, Haley WE (2007) Preserving health of Alzheimer caregivers: impact of a spouse caregiver intervention. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 15: 780–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lingard J, Milne A (2004) First Signs—celebrating the achievements of the Dementia Advice and Support Service: a project for people in the early stages of dementia. London: Mental Health Foundation.

- 16. Dixon-Woods M, Fitzpatrick R (2001) Qualitative research in systematic reviews. Has established a place for itself. BMJ 323: 765–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Steeman E, de Casterle BD, Godderis J, Grypdonck M (2006) Living with early-stage dementia: a review of qualitative studies. J Adv Nurs 54: 722–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Boer ME, Hertogh C, Droes RM, Riphagen II, Jonker C, et al. (2007) Suffering from dementia-the patient's perspective: a review of the literature. Int Psychogeriatr 19: 1021–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robinson L, Gemski A, Abley C, Bond J, Keady J, et al. (2011) The transition to dementia—individual and family experiences of receiving a diagnosis: a review. Int Psychogeriatr 23: 1026–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lecouturier J, Bamford C, Hughes JC, Francis JJ, Foy R, et al. (2008) Appropriate disclosure of a diagnosis of dementia: identifying the key behaviours of ‘best practice’. BMC Health Serv Res 8: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenhalgh T, Peacock R (2005) Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ 331: 1064–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, Dillon L (2003) Quality in qualitative evaluation: a framework for assessing research evidence. London: UK Government Chief Social Researcher's Office. Available: http://www.uea.ac.uk/edu/phdhkedu/acadpapers/qualityframework.pdf. Accessed 18 September 2012.

- 23. Bunn F, Dickinson A, Barnett-Page E, Horton K (2008) A systematic review of older people's perceptions of facilitators and barriers to participation in falls prevention interventions. Ageing Soc 28: 449–472. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pocock M, Trivedi D, Wills W, Bunn F, Magnusson J (2010) Parental perceptions regarding healthy behaviours for preventing overweight and obesity in young children: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev 11: 338–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marston C, King E (2006) Factors that shape young people's sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Lancet 368: 1581–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, Britten N, Pill R, et al. (2003) Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med 56: 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, et al. (2002) Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy 7: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marston C (2004) Gendered communication among young people in Mexico: implications for sexual health interventions. Soc Sci Med 59: 445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas J, Harden A (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adams KB (2006) The transition to caregiving: the experience of family members embarking on the dementia caregiving career. J Gerontol Soc Work 47: 3–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adams T (1994) The emotional experience of caregivers to relatives who are chronically confused—implications for community mental health nursing. Int J Nurs Stud 31: 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adamson J (2001) Awareness and understanding of dementia in African/Caribbean and South Asian families. Health Soc Care Community 9: 391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bamford C, Bruce E (2000) Defining the outcomes of community care: the perspectives of older people with dementia and their carers. Ageing Soc 20: 543–570. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Banningh LJW, Vernooij-Dassen M, Rikkert MO, Teunisse JP (2008) Mild cognitive impairment: coping with an uncertain label. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23: 148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beard RL (2004) In their voices: identity preservation and experiences of Alzheimer's disease. J Aging Stud 18: 415–428. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beard RL, Fetterman DJ, Wu B, Bryant L (2009) The two voices of Alzheimer's: attitudes toward brain health by diagnosed individuals and support persons. Gerontologist 49: S40–S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beard RL, Fox PJ (2008) Resisting social disenfranchisement: negotiating collective identities and everyday life with memory loss. Soc Sci Med 66: 1509–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beattie A, Daker-White G, Gilliard J, Means R (2004) ‘How can they tell?’ A qualitative study of the views of younger people about their dementia and dementia care services. Health Soc Care Community 12: 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Benbow SM, Ong YL, Black S, Garner J (2009) Narratives in a users' and carers' group: meanings and impact. Int Psychogeriatr 21: 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blieszner R, Roberto KA, Wilcox KL, Barham EJ, Winston BL (2007) Dimensions of ambiguous loss in couples coping with mild cognitive impairment. Fam Relat 56: 196–209. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Boise L, Morgan DL, Kaye J, Camicioli R (1999) Delays in the diagnosis of dementia: perspectives of family caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 14: 20. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bowes A, Wilkinson H (2003) ‘We didn't know it would get that bad’: South Asian experiences of dementia and the service response. Health Soc Care Community 11: 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bruce DG, Paterson A (2000) Barriers to community support for the dementia carer: a qualitative study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 15: 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Butcher HK, Holkup PA, Buckwalter KC (2001) The experience of caring for a family member with Alzheimer's disease. West J Nurs Res 23: 33–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Byszewski AM, Molnar FJ, Aminzadeh F, Eisner M, Gardezi F, et al. (2007) Dementia diagnosis disclosure: a study of patient and caregiver perspectives. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 21: 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cahill S, Begley E, Topo P, Saarikalle K, Macijauskiene J, et al. (2004) ‘I know where this is going and I know it won't go back’: hearing the individual's voice in dementia quality of life assessments. Dementia 3: 313–330. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cahill SM, Gibb M, Bruce I, Headon M, Drury M (2008) ‘I was worried coming in because I don't really know why it was arranged’: the subjective experience of new patients and their primary caregivers attending a memory clinic. Dementia 7: 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Clare L (2002) Developing awareness about awareness in early-stage dementia: the role of psychosocial factors. Dementia 1: 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Clare L, Roth I, Pratt R (2005) Perceptions of change over time in early-stage Alzheimer's disease: implications for understanding awareness and coping style. Dementia 4: 487–520. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Clare L, Shakespeare P (2004) Negotiating the impact of forgetting: dimensions of resistance in task-oriented conversations between people with early-stage dementia and their partners. Dementia 3: 211–232. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Corner L, Bond J (2006) The impact of the label of mild cognitive impairment on the individual's sense of self. Philos Psychiatr Psychol 13: 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cotrell V, Lein L (1992) Awareness and denial in the Alzheimer's disease victim. J Gerontol Soc Work 19: 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Deb S, Hare M, Prior L (2007) Symptoms of dementia among adults with Down's syndrome: a qualitative study. J Intellect Disabil Res 51: 726–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Derksen E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Gillissen F, Olde Rikkert M, Scheltens P (2006) Impact of diagnostic disclosure in dementia on patients and carers: qualitative case series analysis. Aging Ment Health 10: 525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Duggan S, Blackman T, Martyr A, Van Schaik P (2008) The impact of early dementia on outdoor life: a ‘shrinking world’? Dementia 7: 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Duggleby W, Williams A, Wright K, Bollinger S (2009) Renewing everyday hope: the hope experience of family caregivers of persons with dementia. Issues Ment Health Nurs 30: 514–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Frank L, Lloyd A, Flynn JA, Kleinman L, Matza LS, et al. (2006) Impact of cognitive impairment on mild dementia patients and mild cognitive impairment patients and their informants. Int Psychogeriatr 18: 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gillies BA (2000) A memory like clockwork: accounts of living through dementia. Aging Ment Health 4: 366–374. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gilmour H, Gibson F, Campbell J (2003) Living alone with dementia: a case study approach to understanding risk. Dementia 2: 403–420. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gilmour JA, Huntington AD (2005) Finding the balance: living with memory loss. Int J Nurs Pract 11: 118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hain D, Touhy TA, Engström G (2010) What matters most to carers of people with mild to moderate dementia as evidence for transforming care. Alzheimers Care Today 11: 162. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Harman G, Clare L (2006) Illness representations and lived experience in early-stage dementia. Qual Health Res 16: 484–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Harris PB, Keady J (2004) Living with early onset dementia: exploring the experience and developing evidence-based guidelines for practice. Alzheimers Care Today 5: 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Harris PB, Sterin GJ (1999) Insider's perspective: defining and preserving the self of dementia. J Ment Health Aging 5: 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hellström I, Nolan M, Lundh U (2005) Awareness context theory and the dynamics of dementia. Dementia 4: 269. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hinton L, Franz C, Friend J (2004) Pathways to dementia diagnosis: evidence for cross-ethnic differences. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 18: 134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hinton WL, Levkoff S (1999) Constructing Alzheimer's: narratives of lost identities, confusion and loneliness in old age. Cult Med Psychiatry 23: 453–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Holst G, Hallberg IR (2003) Exploring the meaning of everyday life, for those suffering from dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 18: 359–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Howorth P, Saper J (2003) The dimensions of insight in people with dementia. Aging Ment Health 7: 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hulko W (2009) From ‘not a big deal’ to ‘hellish’: experiences of older people with dementia. J Aging Stud 23: 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hutchings D, Vanoli A, McKeith I, Brotherton S, McNamee P, et al. (2010) Good days and bad days: the lived experience and perceived impact of treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease in the United Kingdom. Dementia 9: 409–425. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hutchinson SA, Leger-Krall S, Wilson HS (1997) Early probable Alzheimer's disease and awareness context theory. Soc Sci Med 45: 1399–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Jansson W, Nordberg G, Grafström M (2001) Patterns of elderly spousal caregiving in dementia care: an observational study. J Adv Nurs 34: 804–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jutlla K, Moreland N (2007 March) Twice a child III: the experience of Asian carers of older people with dementia in Wolverhampton. London: Dementia UK.

- 75. Katsuno T (2005) Dementia from the inside: how people with early-stage dementia evaluate their quality of life. Ageing Soc 25: 197–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Keady J, Gilliard J (1999) The early experience of Alzheimer's disease: implications for partnership and practice. In: Adams T, Clarke CL, editors. Dementia care: developing partnerships in practice. London: Bailliere Tindall. pp. 227–256.

- 77. Koppel OSB, Dallos R (2007) The development of memory difficulties: a journey into the unknown. Dementia 6: 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Laakkonen ML, Raivio MM, Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Saarenheimo M, Pietilä M, et al. (2008) How do elderly spouse care givers of people with Alzheimer disease experience the disclosure of dementia diagnosis and subsequent care? J Med Ethics 34: 427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Langdon SA, Eagle A, Warner J (2007) Making sense of dementia in the social world: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med 64: 989–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Davis LL, Gilliss CL, Deshefy-Longhi T, Chestnutt DH, Molloy M (2011) The nature and scope of stressful spousal caregiving relationships. J Fam Nurs 17: 224–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. de Witt L, Ploeg J, Black M (2010) Living alone with dementia: an interpretive phenomenological study with older women. J Adv Nurs 66: 1698–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Leung KK, Finlay J, Silvius JL, Koehn S, McCleary L, et al. (2011) Pathways to diagnosis: exploring the experiences of problem recognition and obtaining a dementia diagnosis among Anglo-Canadians. Health Soc Care Community 19: 372–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kuo LM, Shyu YI (2010) Process of ambivalent normalisation: experience of family caregivers of elders with mild cognitive impairment in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs 19: 3477–3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Roberto KA, Blieszner R, McCann BR, McPherson MC (2011) Family triad perceptions of mild cognitive impairment. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 66: 756–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lawrence V, Murray J, Samsi K, Banerjee S (2008) Attitudes and support needs of Black Caribbean, south Asian and White British carers of people with dementia in the UK. Br J Psychiatry 193: 240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lawrence V, Samsi K, Banerjee S, Morgan C, Murray J (2010) Threat to valued elements of life: the experience of dementia across three ethnic groups. Gerontologist 51: 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lingler JH, Nightingale MC, Erlen JA, Kane AL, Reynolds CF 3rd, et al. (2006) Making sense of mild cognitive impairment: a qualitative exploration of the patient's experience. Gerontologist 46: 791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Livingston G, Leavey G, Manela M, Livingston D, Rait G, et al. (2010) Making decisions for people with dementia who lack capacity: qualitative study of family carers in UK. BMJ 341: c4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lu YF, Haase JE (2009) Experience and perspectives of caregivers of spouse with mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res 6: 384–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. MacQuarrie CR (2005) Experiences in early stage Alzheimer's disease: understanding the paradox of acceptance and denial. Aging Ment Health 9: 430–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. MacRae H (2010) Managing identity while living with Alzheimer's disease. Qual Health Res 20: 293–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Mahoney DF, Cloutterbuck J, Neary S, Zhan L (2005) African American, Chinese, and Latino family caregivers' impressions of the onset and diagnosis of dementia: cross-cultural similarities and differences. Gerontologist 45: 783–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Manthorpe J, Samsi K, Campbell S, Abley C, Keady J, et al.. (2011) The transition from cognitive impairment to dementia: older people's experiences. Southampton: NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme.

- 94. Mason E, Clare L, Pistrang N (2005) Processes and experiences of mutual support in professionally-led support groups for people with early-stage dementia. Dementia 4: 79–112. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Menne HL, Kinney JM, Morhardt DJ (2002) ‘Trying to continue to do as much as they can do’: theoretical insights regarding continuity and meaning making in the face of dementia. Dementia 1: 367–382. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Mok E, Lai CK, Wong FL, Wan P (2007) Living with early-stage dementia: the perspective of older Chinese people. J Adv Nurs 59: 591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Moniz-Cook E, Manthorpe J, Carr I, Gibson G, Vernooij-Dassen M (2006) Facing the future: a qualitative study of older people referred to a memory clinic prior to assessment and diagnosis. Dementia 5: 375. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moreland N (2001) Twice a child: dementia care for African-Caribbean and Asian older people in Wolverhampton. London: Dementia UK.

- 99.Moreland N (2003) Twice a child II: service development for dementia care for African-Caribbean and Asian older people in Wolverhampton. London: Dementia UK.

- 100. Mukadam N, Cooper C, Basit B, Livingston G (2011) Why do ethnic elders present later to UK dementia services? A qualitative study. Int Psychogeriatr 23: 1070–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Murray J, Schneider J, Banerjee S, Mann A (1999) EUROCARE: a cross-national study of co-resident spouse carers for people with Alzheimer's disease: II—a qualitative analysis of the experience of caregiving. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 14: 662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Neufeld A, Harrison MJ (2003) Unfulfilled expectations and negative interactions: nonsupport in the relationships of women caregivers. J Adv Nurs 41: 323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Nygard L, Borell L (1998) A life-world of altering meaning: expressions of the illness experience of dementia in everyday life over 3 years. Occup Ther J Res 18: 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 104. O'Connor DL (1999) Living with a memory-impaired spouse: (re)cognizing the experience. Can J Aging 18: 211–235. [Google Scholar]

- 105. Ostwald SK, Duggleby W, Hepburn KW (2002) The stress of dementia: view from the inside. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 17: 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Pearce A, Clare L, Pistrang N (2002) Managing sense of self: coping in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Dementia 1: 173. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Perry J, O'Connor D (2002) Preserving personhood: (re)membering the spouse with dementia. Fam Relat 51: 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Phinney A (1998) Living with dementia: from the patient's perspective. J Gerontol Nurs 24: 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Phinney A (2006) Family strategies for supporting involvement in meaningful activity by persons with dementia. J Fam Nurs 12: 80–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Pollitt PA, O'Connor DW, Anderson I (1989) Mild dementia: perceptions and problems. Ageing Soc 9: 261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 111. Post SG, Stuckey JC, Whitehouse PJ, Ollerton S, Durkin C, et al. (2001) A focus group on cognition-enhancing medications in Alzheimer disease: disparities between professionals and consumers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 15: 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Pratt R, Wilkinson H (2003) A psychosocial model of understanding the experience of receiving a diagnosis of dementia. Dementia 2: 181. [Google Scholar]

- 113. Preston L, Marshall A, Bucks RS (2007) Investigating the ways that older people cope with dementia: a qualitative study. Aging Ment Health 11: 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Quinn C, Clare L, Pearce A, van Dijkhuizen M (2008) The experience of providing care in the early stages of dementia: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Aging Ment Health 12: 769–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Robinson L, Clare L, Evans K (2005) Making sense of dementia and adjusting to loss: psychological reactions to a diagnosis of dementia in couples. Aging Ment Health 9: 337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Robinson P, Ekman SL, Meleis AI, Winblad B, Wahlund LO (1997) Suffering in silence: the experience of early memory loss. Health Care Later Life 2: 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Samuelsson AM, Annerstedt L, Elmståhl S, Samuelsson SM, Grafström M (2001) Burden of responsibility experienced by family caregivers of elderly dementia sufferers. Scand J Caring Sci 15: 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Seabrooke V, Milne A (2004) Culture and care in dementia: a study of the Asian community in north west Kent. London: The Mental Health Foundation.

- 119. Shaji KS, Smitha K, Lal KP, Prince MJ (2003) Caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease: a qualitative study from the Indian 10/66 Dementia Research Network. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 18: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Smith AP, Beattie BL (2001) Disclosing a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: patient and family experiences. Can J Neurol Sci 28 Suppl 1: S67–S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Steeman E, Godderis J, Grypdonck M, De Bal N, Dierckx de Casterle B (2007) Living with dementia from the perspective of older people: is it a positive story? Aging Ment Health 11: 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Sterritt PF, Pokorny ME (1998) African-American caregiving for a relative with Alzheimer's disease. Geriatr Nurs 19: 127–124, 127-128, 133-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Svanstrom R, Dahlberg K (2004) Living with dementia yields a heteronomous and lost existence. West J Nurs Res 26: 671–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Teel CS, Carson P (2003) Family experiences in the journey through dementia diagnosis and care. J Fam Nurs 9: 38. [Google Scholar]

- 125. Todres L, Galvin K (2006) Caring for a partner with Alzheimer's disease: intimacy, loss and the life that is possible. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 1: 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- 126. Van Dijkhuizen M, Clare L, Pearce A (2006) Striving for connection: appraisal and coping among women with early-stage Alzheimer's disease. Dementia 5: 73. [Google Scholar]

- 127. Vellone E, Sansoni J, Cohen MZ (2002) The experience of Italians caring for family members with Alzheimer's disease. J Nurs Scholarsh 34: 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Watkins R, Cheston R, Jones K, Gilliard J (2006) ‘Coming out’ with Alzheimer's disease: changes in awareness during a psychotherapy group for people with dementia. Aging Ment Health 10: 166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Werezak L, Stewart N (2002) Learning to live with early dementia. Can J Nurs Res 34: 67–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Westius A, Andersson L, Kallenberg K (2009) View of life in persons with dementia. Dementia 8: 481–500. [Google Scholar]

- 131. Wolverson EL, Clarke C, Moniz-Cook E (2010) Remaining hopeful in early-stage dementia: a qualitative study. Aging Ment Health 14: 450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Aminzadeh F, Byszewski A, Molnar FJ, Eisner M (2007) Emotional impact of dementia diagnosis: exploring persons with dementia and caregivers' perspectives. Aging Ment Health 11: 281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Blieszner R, Roberto KA (2010) Care partner responses to the onset of mild cognitive impairment. Gerontologist 50: 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Clare L (2002) We'll fight it as long as we can: coping with the onset of Alzheimer s disease. Aging Ment Health 6: 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Clare L (2003) ‘I'm still me’: living with the onset of dementia. J Dement Care 11: 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 136. Clare L (2003) Managing threats to self: awareness in early stage Alzheimer's disease. Soc Sci Med 57: 1017–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Cloutterbuck J, Mahoney DF (2003) African American dementia caregivers: the duality of respect. Dementia 2: 221. [Google Scholar]

- 138. Connell CM, Boise L, Stuckey JC, Holmes SB, Hudson ML (2004) Attitudes toward the diagnosis and disclosure of dementia among family caregivers and primary care physicians. Gerontologist 44: 500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Derksen E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Gillissen F, Olde-Rikkert M, Scheltens P (2005) The impact of diagnostic disclosure in dementia: a qualitative case analysis. Int Psychogeriatr 17: 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Fox K, Hinton WL, Levkoff S (1999) Take up the caregiver's burden: stories of care for urban African American elders with dementia. Cult Med Psychiatry 23: 501–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Galvin K, Todres L, Richardson M (2005) The intimate mediator: a carer's experience of Alzheimer's. Scand J Caring Sci 19: 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Harris PB, Keady J (2009) Selfhood in younger onset dementia: transitions and testimonies. Aging Ment Health 13: 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Hellstrom I, Nolan M, Lundh U (2005) ‘We do things together’: a case study of ‘couplehood’ in dementia. Dementia 4: 7. [Google Scholar]

- 144. Hellström I, Nolan M, Lundh U (2007) Sustaining ‘couplehood’. Dementia 6: 383. [Google Scholar]

- 145. Hicks MH, Lam MS (1999) Decision-making within the social course of dementia: accounts by Chinese-American caregivers. Cult Med Psychiatry 23: 415–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Jolley D, Moreland N, Read K, Kaur H, Jutlla K, et al. (2009) The ‘Twice a Child’ projects: learning about dementia and related disorders within the black and minority ethnic population of an English city and improving relevant services. Ethn Inequal Health Soc Care 2: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 147. Neary SR, Mahoney DF (2005) Dementia caregiving: the experiences of Hispanic/Latino caregivers. J Transcult Nurs 16: 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Ortiz A, Simmons J, Hinton WL (1999) Locations of remorse and homelands of resilience: notes on grief and sense of loss of place of Latino and Irish-American caregivers of demented elders. Cult Med Psychiatry 23: 477–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Phinney A (2002) Fluctuating awareness and the breakdown of the illness narrative in dementia. Dementia 1: 329–344. [Google Scholar]

- 150. Phinney A, Chaudhury H, O'Connor DL (2007) Doing as much as I can do: the meaning of activity for people with dementia. Aging Ment Health 11: 384–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Phinney A, Chesla CA (2003) The lived body in dementia. J Aging Stud 17: 283–299. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Pratt R, Wilkinson H (2001) ‘Tell me the truth’: the effect of being told the diagnosis of dementia from the perspective of the person with dementia. London: The Mental Health Foundation.

- 153. Robinson P, Ekman SL, Wahlund LO (1998) Unsettled, uncertain and striving to understand: toward an understanding of the situation of persons with suspected dementia. Int J Aging Hum Dev 47: 143–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Vernooij-Dassen M, Derksen E, Scheltens P, Moniz-Cook E (2006) Receiving a diagnosis of dementia: the experience over time. Dementia 5: 397. [Google Scholar]

- 155. De Witt L, Ploeg J, Black M (2009) Living on the threshold: the spatial experience of living alone with dementia. Dementia 8: 263–291. [Google Scholar]

- 156. Barroso J, Gollop CJ, Sandelowski M, Meynell J, Pearce PF, et al. (2003) The challenges of searching for and retrieving qualitative studies. West J Nurs Res 25: 153–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Wong SS, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB (2004) Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in MEDLINE. Stud Health Technol Inform 107: 311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Dixon-Woods M, Shaw RL, Agarwal S, Smith JA (2004) The problem of appraising qualitative research. Qual Saf Health Care 13: 223–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.UK Department of Health (2009) Living well with dementia—the National Dementia Strategy Joint commissioning framework for dementia. London: UK Department of Health.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA checklist.

(DOC)

Protocol for the review.

(DOC)

Characteristics of included studies.

(DOCX)

Themes and supporting evidence. This table shows the themes that arose from our analysis and the evidence to support them.

(DOCX)

Examples of quotations illustrating themes and author interpretations of findings. This table provides examples of quotes supporting the themes from our analysis and gives examples of the ways authors of our included studies interpreted their findings.

(DOCX)