Abstract

Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders have been gaining increased attention and empirical study in recent years. Despite this, all of the research on transdiagnostic anxiety treatments to date have either not used a control condition, or have relied on no-treatment or delayed-treatment controls, thus limiting inferences about comparative efficacy. The current study was a randomized clinical trial examining the efficacy of a 12-week transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral group treatment in comparison to a 12-week comprehensive relaxation training program. Results from 87 treatment initiators suggested significant and statistically equivalent/non-inferior outcomes across conditions, although relaxation was associated with a greater rate of dropout despite no differences in treatment credibility. No evidence was found for any differential effects of transdiagnostic CBT for any primary or comorbid diagnoses.

The release of DSM-III in 1980 (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1980) with its increased diagnostic classification yielded a new era of increasingly focused psychosocial and pharmacological treatment models designed to specifically target the individual diagnoses. This has been particularly notable within the domain of anxiety disorders, as DSM-III expanded the classification structure from three anxiety-related neuroses to nine distinct diagnoses. Subsequent revisions (APA, 1987, 1994) have revised and expanded the specificity of the diagnostic system such that there are twelve anxiety disorder diagnoses and over 25 subtypes and specified categories. Treatments designed specifically for these diagnoses (e.g., Andrews et al., 1994; Craske & Barlow, 2006; Craske, Barlow, & Zinbarg, 1992; Craske, Antony, & Barlow, 1997; Foa & Kozak, 1997; Hope, Heimberg, Turk, & Juster, 2000; Resick & Schnicke, 1993), particularly cognitive-behavioral treatments (CBT), arose quickly and are currently seen as the most efficacious and effective interventions for these diagnoses (Norton & Price, 2007; Hofmann & Smits, 2008).

Although the efficacy of these diagnosis-specific anxiety treatments is very well established (e.g., Norton & Price, 2007), concerns have been raised about whether the increase in anxiety disorder diagnoses has led to more efficacious treatments tailored or delivered to specific diagnoses. Indeed, Tyrer (1988) critiqued the diagnostic system by showing that identical pharmacological and cognitive-behavioral treatments did not differentially impact patients with varied DSM-III anxiety disorder diagnoses. Subsequently, several researchers and teams have generated an impressive body of genetic (Jang, 2005), etiological (Clark & Watson, 1991; Chorpita & Barlow, 1998), comorbidity (Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001), and treatment (Borkovec, Abel, & Newman, 1995; Brown, Antony, & Barlow, 1995) evidence suggesting that anxiety disorders either share a common underlying element or are superficially different manifestations of the same pathology; that is, fears of contamination and arachnids are both simply fears, and their corresponding behavioral manifestations (washing versus escape) are stimulus-appropriate approaches to minimize or negate the perceived threat (for reviews, see Norton, 2006; Moses & Barlow, 2006).

From this conceptualization, several independent laboratories have begun to develop transdiagnostic, unified, or broad-spectrum interventions designed to tailor treatment to the alleged core pathology underlying anxiety disorder while dismissing the necessity of specific diagnostic categories (e.g., Erickson, 2003; Erickson, Janeck, & Tallman, 2007; Norton, 2008; Norton, Hayes, & Hope, 2004; Norton & Hope, 2005; Lumpkin, Silverman, Weems, Markham, & Kurtines, 2002; Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, & Preston, this issue). While similar to diagnosis-specific CBT for anxiety disorders in content and presumed mechanism of action, transdiagnostic CBT programs differ from diagnosis-specific CBT in their delivery; that is, CBT protocols that can be delivered to individuals or groups experiencing a range of anxiety presentations. Indeed, within the child anxiety literature, CBT protocols that are not bound to specific diagnoses have been commonplace for decades (e.g., Kendall, 1990). Among the most empirically evaluated of the adult transdiagnostic CBT protocols was developed by Norton and Hope (2002). Norton and Hope (2005) published the first randomized controlled trial of a 12-week transdiagnostic group treatment and found that, compared to waitlist controls (n = 11), clients receiving treatment (n = 12) improved significantly. Roughly 67% of those receiving treatment, as compared to none of the waitlist controls, showed a reduction in diagnostic severity to subclinical levels, and significant improvement was also noted on several indices of anxiety. Unfortunately, the small sample size of this study (n = 23) precluded analyses of outcome by diagnosis. In a secondary analysis of the treatment data, Norton et al. (2004) also noted significant decreases in depressive symptoms and the diagnostic severity of depressive disorders among those receiving treatment. Recently, Norton (2008) reported the results of an open trial of the transdiagnostic CBGT using mixed-effects regression modeling of session-by-session anxiety data from 52 participants with an anxiety disorder (predominantly panic disorder [42.3%] and social phobia [48.1%]). Results indicated that participants tended to improve over treatment, with no differential outcome for any primary or comorbid diagnoses. Effect sizes were very high (d = 1.68) and comparable to average treatment effects reported in meta-analyses of diagnosis-specific CBT for the anxiety diagnoses (see Norton & Price, 2007; Hofmann & Smits, 2008).

In addition, other research centers have begun to develop and empirically evaluate the efficacy of independent group and individual transdiagnostic treatments. Erickson (2003), for example, reported the results of an uncontrolled trial of a transdiagnostic group CBT program for 70 individuals with an anxiety disorder diagnosis. His results suggested significant decreases in self-reported anxiety and depression among clients completing the 11-week treatment. Further, six-month follow-up data from 16 participants suggested maintenance of treatment gains. No analyses of outcome by diagnosis were conducted. Erickson, Janeck, and Tallman (2007) then randomized 152 patients to either an 11-week CBGT program or a delayed treatment control condition. The immediate treatment group improved more than the delayed treatment controls. When diagnostic categories were examined separately, however, only patients with primary panic disorder showed greater improvement than controls, possibly due to the reduced sample sizes of these subgroup analyses. Lumpkin et al. (2002) reported similar treatment effects following a 12-week transdiagnostic individual treatment with anxious youths. Multiple baseline results suggested notable reductions on measures of anxiety occurring during treatment after stable baseline periods. As well, treatment gains were maintained at 6 and 12-months. Again, no analyses by diagnosis were conducted.

In the outcome trial using the highest standard of comparison to date, McEvoy and Nathan (2007) utilized a benchmarking strategy—comparing observed effect sizes to those obtained from methodologically-similar studies—to compare the efficacy of their transdiagnostic CBT intervention for anxiety and depression to similar published efficacy trials. Data from 143 participants attending at least three sessions (30 with anxiety disorders, 38 with depressive disorders, 75 with comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders) indicated treatment effect sizes, reliable change indices, and clinically significant change indices that were highly similar to those obtained in methodologically similar diagnosis-specific treatment studies for major depressive disorder or specific anxiety disorder diagnoses.

Overall, the published and unpublished data reported thus far converge on the conclusion that participants undertaking transdiagnostic treatment programs for anxiety disorders show significant improvement, and that such change is greater than that experienced by control participants not receiving treatment (see McEvoy, Nathan, & Norton, 2009). Indeed, Norton and Philipp (2008) reported a meta-analysis on the efficacy of transdiagnostic anxiety treatments, and noted a strong average treatment effect (d = 1.29) across studies. What is much less well established, however, is the comparative efficacy of transdiagnostic anxiety treatments with other established treatment models. As noted earlier, McEvoy and Nathan (2007) utilized a benchmarking strategy to suggest that their treatment protocol yielded similar change as do diagnosis-specific CBT, while Norton and Philipp (2008) reported meta-analytic results suggesting that effect sizes from transdiagnostic treatments were similar to those reported in meta-analyses of diagnosis-specific CBT for anxiety (e.g., Norton & Price, 2007). Unfortunately, none of the studies of transdiagnostic anxiety treatment efficacy have employed an active treatment comparison condition, thereby limiting the extent to which equivalence or non-inferiority of the transdiagnostic treatments can be established.

In attempting to evaluate the comparative efficacy of transdiagnostic CBT, two avenues are apparent. First, the transdiagnostic treatment can be compared directly to diagnosis-specific CBT conditions. Such a comparative outcomes trial (at least one is currently underway) would require extensive sample sizes to ensure adequate statistical power and representation of all diagnoses in both the transdiagnostic and diagnosis-specific conditions. Second, a randomized clinical trial could compare the efficacy of transdiagnostic CBT to another form of transdiagnostic treatment such as a comprehensive applied relaxation training program (RLX). The current paper describes an outcome trial adopting this latter approach.

RLX-based treatments appear to be losing popularity as stand-alone treatment programs for anxiety disorders. This may be a function of data suggesting that relaxation components, as part of a larger treatment package, have not shown incremental benefit over exposure and cognitive therapy components (e.g., Borkovec, Newman, Pincus, & Lytle, 2002; Craske, Rowe, Lewin, & Noriega-Dimitri, 1997; de Ruiter, Ryken, Garssen, & Kraaimaat, 1989; Foa et al., 1999). Indeed, Schmidt et al. (2000) reported evidence that one relaxation skill, breathing retraining, may in fact attenuate treatment response for panickers undergoing panic control therapy. However, full relaxation training programs, as opposed to brief relaxation components in larger CBT models, have shown strong and generally comparable efficacy to CBT approaches.

Using a sample of 64 panic disorder patients randomized to either relaxation therapy, cognitive therapy, or minimal contact, Beck, Stanley, Baldwin, Deagle, and Averill (1994) reported few differences in panic frequency, panic free status, and Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale scores between those receiving RLX or CBT. Similar evidence of equivalence has been reported by Öst and Westling (1995) and Öst, Westling, and Hellström (1993) for panic disorder, although Clark et al. (1994) found evidence that cognitive therapy was superior to applied relaxation and imipramine, which showed no difference from each other and were both superior to a waitlist control condition. In a meta-analysis of five studies comparing CBT and RLX for panic disorder, Siev and Chambless (2007) concluded a superiority of CBT, although this result may have been skewed by aforementioned Clark et al. (1994) results which showed standardized mean difference effect sizes over three times higher than in any of the four other comparative outcome trials of CBT and RLX for panic disorder. Borkovec and Costello (1993) and Arntz (2003) suggest similar efficacy between CBT and RLX for generalized anxiety disorder, a conclusion supported by the Siev and Chambless (2007) meta-analysis. Wolitzky-Taylor, Horowitz, Powers, and Telch (2008) provided evidence that relaxation may be efficacious, albeit not as efficacious as exposure-based treatments, for specific phobias. Relaxation training has not shown equivalent efficacy with cognitive therapy or exposure therapy for OCD (Griest et al., 2002) and the data are equivocal but not promising for PTSD (Marks et al., 1998). Few trials have examined relaxation training for social anxiety disorder, although Jerremalm, Jansson, and Öst (1986) did find evidence for similar outcomes among social phobics treated with applied relaxation and a rudimentary cognitive therapy. Federoff and Taylor (2001) reported meta-analytic results suggesting that applied relaxation was inferior to cognitive and/or behavioral techniques among clients with social phobia.

Across these aforementioned studies, however, it should be noted that the definitions and dosages of relaxation therapy varied considerably, from weekly in-session practice and twice-daily homework practice (e.g., Beck et al., 1994) to listening to audiotapes and once-daily homework practice (e.g., Marks et al., 1998), thereby limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. In the Norton and Price (2007) meta-analysis, RLX conditions did not show differential efficacy from CBT conditions, with the possible exception of RLX for OCD wherein a trend toward superiority of CBT was observed. Only one trial of RLX for OCD, and no trials of RLX for social phobia, met criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

The primary aim of the current study was therefore to further add to the growing evidence base underlying transdiagnostic treatments by investigating the efficacy of a transdiagnostic anxiety treatment by comparison to a 12-week comprehensive RLX treatment program using a treatment equivalence/non-inferiority methodology (see Piaggio, Elbourne, Altman, Pocock, & Evans, 2006). Secondary aims were to compare treatment conditions on treatment credibility and acceptability, and to further compare transdiagnostic CBT effects across diagnoses to examine for possible differential efficacy by diagnosis. It was hypothesized that participants would show a significant reduction in anxiety over the course of treatment, and that CBT would demonstrate treatment equivalence/non-inferiority with RLX. It was also hypothesized that, consistent with Norton (2008), no differences in outcome would be observed by primary or secondary diagnosis.

Method

Participants

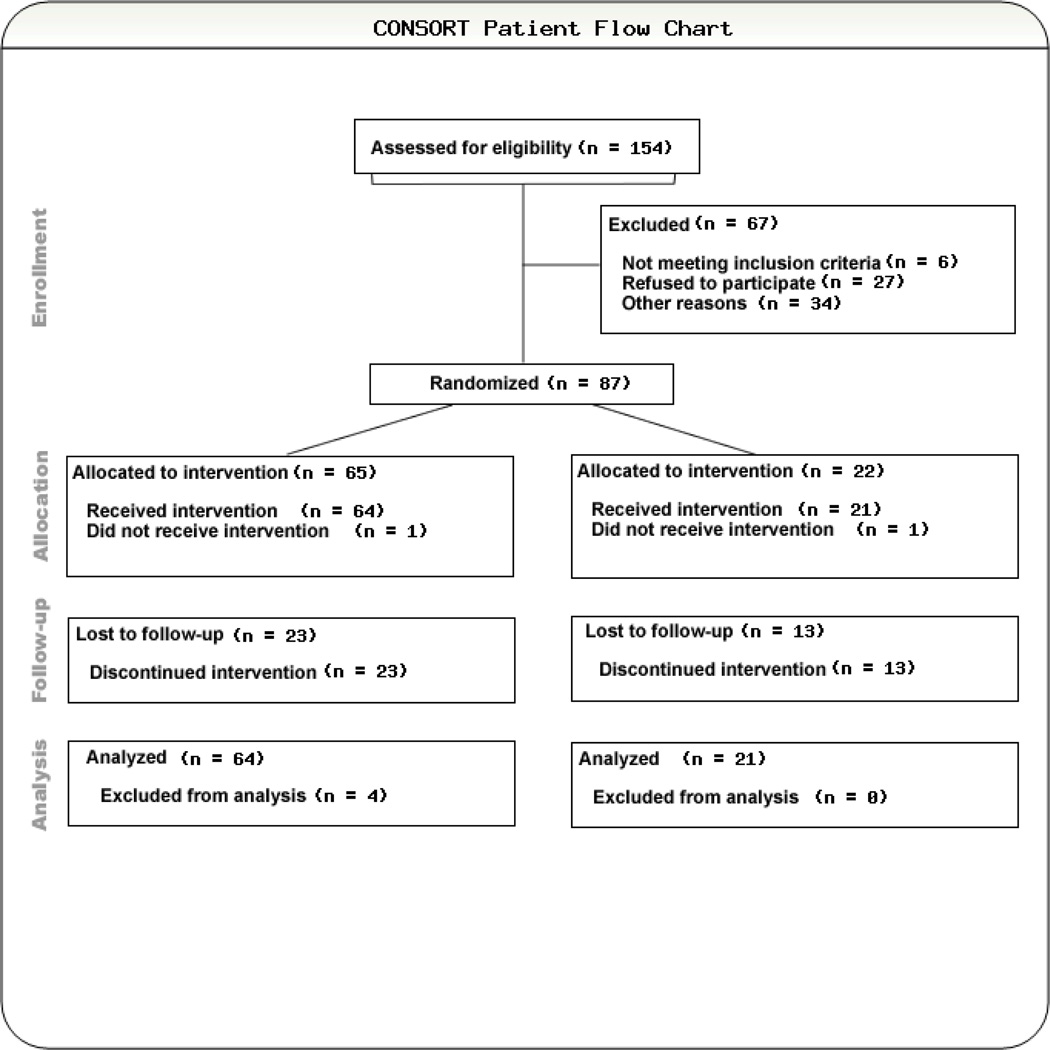

Participants were drawn from 154 individuals contacting the University of Houston Anxiety Disorder Clinic between October 2006 and April 2009 for possible treatment services. Participants were recruited for participation via advertisements and articles in local and neighborhood newspapers, referrals from health and mental health professions, and public service media announcements. The following criteria were established for inclusion in the study: (a) age 18 or older, (b) principal DSM-IV diagnosis of any anxiety disorder, (c) adequate proficiency in English, (d) no evidence of dementia or other neurocognitive conditions that would impair ability to provide informed consent or participate in treatment, (e) absence of serious suicidality, substance use disorder, or other conditions that would require immediate intervention, and (f) willingness to be randomized to group CBT or relaxation treatment conditions. Figure 1 presents the CONSORT flowchart of patient disposition: six individuals contacting the clinic did not meet study eligibility, 27 declined participation and were either seen individually or referred for other services, and 34 were lost to further contact (i.e., did not present for or complete pre-treatment assessment). This left a randomization sample of 87, with one participant in each condition not presenting for any services, and four participants in the CBT condition and one in the RLX condition only presenting for a single session (yielding insufficient data for analysis).

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flowchart of patient disposition.

The randomized initiator sample of consisted of 33 men and 54 women, and was somewhat racially diverse (58.6% Caucasian, 21.8% Hispanic/Latino(a), 9.2% African American, 4.6% Asian American, and 5.7% Other or Mixed). The sample ranged in age from 18 to 62 years old, with a mean of 32.98 (SD = 10.73). Most were single (48.3%) or married (35.6%), and were fairly well educated (36.4% some undergraduate, 24.1% Bachelors degree or equivalent, 8.0% some professional/graduate school, 11.5% graduate/professional degree).

Participants were randomly assigned by the investigator to treatment condition on a 2:1 (CBT : RLX) ratio blocked by primary diagnosis. The imbalanced randomization schedule was conducted to ensure that a sufficient number of participants were in the transdiagnostic treatment condition to permit analyses of CBT outcome by diagnosis. When a sufficient number (e.g., 6) of participants had completed the assessments and been randomized to either CBT or RLX, they were assigned to begin group sessions together. In some cases, groups were overloaded or started with fewer than 6 participants due to variations in patient flow (i.e., being unwilling to delay treatment further if no further intakes were scheduled). In all, clients from 12 CBT (n =65) and 6 RLX (n = 22) groups participated in the current study. Assessors at pre- and post-treatment were blind to randomly assigned treatment condition.

Measures

All participants received a structured diagnostic assessment at intake, the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV; Brown, Di Nardo, & Barlow, 1994) and Clinician Severity Ratings for each diagnosis (CSR), and completed one self-report measure, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – state version (STAI; Spielberger, 1983) immediately prior to the beginning of each session. Additionally, participants completed several self-report anxiety measures at pre, mid (week 6), and post-treatment.

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV; Brown, Di Nardo, & Barlow, 1994) is a semi-structured diagnostic interview designed to assess the presence, nature, and severity of DSM-IV anxiety, mood, and somatoform disorders, as well as previous mental health history. The interview also contains a brief screen for psychotic symptoms, and alcohol or substance abuse. All ADIS-IV interviewers, advanced doctoral students, were trained to reliability standards by observing an interview conducted by an experienced interviewer then conducting at least three interviews under observation. A reliable match involved matching the experienced interviewer on diagnoses and matching the Clinician Severity Rating (CSR; see below) within 1 point for the primary diagnosis. A recent large scale analysis of the ADIS-IV offers strong support for the reliability of diagnoses using the ADIS-IV (Brown, Di Nardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001).

Clinician Severity Ratings (CSR), a component of the ADIS-IV, are subjective ratings applied by diagnosticians to quantify the degree of severity for each disorder diagnoses with the ADIS-IV. CSR range from 0 (not at all severe) to 8 (extremely severe/distressing). A CSR of 4 (moderate impairment) is generally considered the cut-off for a disorder of clinical significance (e.g., Heimberg et al., 1990). Diagnosticians also completed the Global Impressions (CGI; National Institute of Mental Health, 1985) scale, a clinician-rated measure of overall severity and therapeutic improvement.

Graduate therapists blind to treatment condition assessed reliability of the ADIS-IV diagnoses. The reliability therapists observed and coded DVDs of a random subset of diagnostic interviews. A reliable match involved matching the experienced interviewer on the same primary and comorbid diagnoses and matching the CSR within 1 point for the primary diagnosis. Analyses indicated that diagnostic agreement was very high (86% agreement).

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – State Version

The state form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Luschene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1993) is a 20-item measure designed to assess state anxiety. STAI items are scored on 1 (Not at all) to 4 (Very much so) scales of how much each statement indicates how the participant feels at that moment, with a total score ranging from 20 to 80. The psychometric properties of the STAI-S are strong across multiple populations (Spielberger et al., 1993) with anxiety disorder sample means ranging from 44 to 61 (see Antony, Orsillo, & Roemer, 2001). The measure has demonstrated sensitivity to treatment effects (e.g., Fischer & Durham, 1999). At the initial time-point (Session 1), the STAI was highly internally consistent in this sample (α = .95). The STAI was administered immediately prior to each treatment session.

Self-report outcome measures

At pre, mid (week 6), and post-treatment assessment points participant completed a battery of self-report questionnaires, including the Anxiety Disorder Diagnostic Questionnaire (ADDQ; Norton & Robinson, 2010; pre-treatment α = .79), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck, Epstein, Brown, Steer, 1988; pre-treatment α = .93), Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS; Shear et al., 1997; pre-treatment α = .89), Social Phobia Diagnostic Questionnaire (SPDQ; Newman, Kachin, Zuellig, Constantino, & Cashman-McGrath, 2003; pre-treatment α = .98), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire for DSM-IV (GAD-Q-IV; Roemer, Borkovec, Posa, & Borkovec, 1995; pre-treatment α = .82). All of these measures have demonstrated excellent reliability and validity, and have sensitivity to clinical change in CBT trials.

Treatment credibility measure

Treatment credibility was assessed using the Borkovec and Nau (1972) 4-item measure of treatment rationale credibility. This measure has been used in several anxiety treatment outcome trials to assess the credibility of comparison conditions and psychological placebo conditions (Butler et al., 1984; Heimberg et al., 1990).

Procedure

Assessment and treatment were conducted at the University of Houston Anxiety Disorder Clinic. All methods and procedures were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Houston. All potential participants underwent a brief telephone screen to provide initial evidence of suitability for the study. Potential participants who appeared to be eligible for participation were scheduled for the structured diagnostic evaluation and given the self-report questionnaires to complete. Following the evaluation, participants eligible for participation were randomly assigned to either a group transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral condition or a group relaxation training condition. The study was reviewed by the University of Houston Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Treatment protocols and therapists

Treatment in the transdiagnostic CBT condition consisted of 12 weekly two-hour sessions following a manualized treatment protocol (Norton & Hope, 2002; for a description and group case example, see Norton & Hope, 2008). This protocol deemphasizes diagnostic labels, and focuses instead on challenging and confronting feared stimuli regardless of their specific nature. Indeed, clients are encouraged to conceptualize their own network of fears, and those of the others in the group, as “an excessive or irrational fear of [blank]” rather than as, for example, “panic disorder with comorbid OCD.”

Over the first nine sessions of treatment, three core ingredients of CBT were utilized: psychoeducation and self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring, and exposure to feared stimuli. Although the composition of the groups differs from diagnosis-specific CBT, and the protocol adopts a more individualized case formulation stance (e.g., Persons & Tompkins, 1997), the mechanisms of action are similar to those of diagnosis-specific CBT protocols. Psychoeducation focuses on the nature of anxiety and anxiety disorders, and the components of treatment and their purpose. During the first session, the concept of a fear-avoidance hierarchy is discussed, and each client develops a hierarchy with assistance from the therapists. Cognitive restructuring emphasizes identifying fear-related automatic thoughts and challenging evidence of catastrophic thinking and over-estimating probabilities of negative outcomes. Exposure, which is conducted in vivo or through role-played, imaginal, or interoceptive methods depending on client needs and the nature of the feared stimuli, is conducted in session and assigned as part of weekly homework exercises. During the final sessions, the focus shifts from the presenting fear to the underlying perceptions of uncontrollability, unpredictability, and threat. This phase of treatment utilizes cognitive techniques to identify and challenge core beliefs regarding threat, negativity, and personal control over events.

Treatment in the RLX condition was developed based on the relaxation protocol developed by Bernstein and Borkovec (1973) and the Changeways Relaxation program of Paterson (1997). RLX was framed within the Educational-Supportive treatment manual developed by Zollo, Dodge, Kennedy, Heimberg, and Becker (unpublished) and used as a credible attention-placebo condition by Heimberg et al. (1990) to add non-specific therapy elements beyond the simple application of the RLX exercises. The Educational-Supportive manual was modified to reduce the specific focus on social anxiety, and was selected because it has no CBT elements. Each session, a topic relevant to anxiety disorder was discussed and applied to each clients’ fears (e.g., Physiological Factors in Anxiety) after which relaxation training commenced. Relaxation began with 12 group progressive muscle relaxation script that was practiced in session and assigned for homework at least once daily. Participants were given an audio CD containing a professional narration of the relaxation scripts1. During subsequent sessions, the number of muscle groups was decreased (8 muscle groups, 4 muscle groups, and then full-body cue-controlled relaxation) and similar audio CDs were provided for homework practice. Subsequent sessions utilized passive muscle relaxation (long form then short form), guided imagery relaxation, and four stage breathing retraining. As with the CBT condition, RLX consisted of 12 weekly 2-hour sessions.

Therapists in this trial were doctoral-level graduate students under the supervision of the study author, a Ph.D. level clinical psychologist. All therapists were trained in the treatment protocols through video observation of previous groups, and were then paired with senior graduate student co-therapists who had previously delivered the treatment. The study author directly observed all sessions for supervision purposes and to ensure treatment fidelity, but did not conduct any assessment or treatment.

Data Analysis

Treatment equivalence/non-inferiority methodologies differ from traditional null hypothesis significance testing approaches in that not significantly different is not synonymous with equivalent. Many factors, including sample size, alpha corrections, and within-group variability, could influence whether or not the null hypothesis was retained despite potentially clinically-significant differences in outcome. Equivalence/non-inferiority models set a “prestated margin of noninferiority (Δ)” (Piaggio et al., 2006; p. 1153) to determine a maximum difference in outcomes that would be considered as not clinically significant. Mean differences, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) around those means, are then utilized to identify if mean differences in outcomes suggest superiority, non-inferiority, inconclusive results, or clear inferiority (see Piaggio et al., 2006 and Wiens, 2002 for more thorough discussions). In setting Δ, a meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders was consulted. Norton and Price (2007) estimated a mean effect of RLX treatments of d = 1.60, SD = 1.14, yielding a 95% confidence interval of ± 0.69 or approximately 0.6 SD. Δ was therefore set at 0.6 SD above the RLX mean for each analysis.

To fully utilize the entire sample of treatment initiators, session-by-session STAI measures were examined using Mixed-effect Regression Modeling (MRM). MRM can be conceptualized as an extension of linear regression, but with the incorporation of individual-level effects in addition to group-level effects. In essence, individual regression lines are modeled for each participant, such that their severity and change can be expressed as a combination of individual intercept and slope parameters, thereby providing estimates of both the intercept and slope of the sample as well as estimates of the average deviations of individual participants from these intercepts and slopes. Individual data are nested within treatment groups to partial out group-level effects. Missing data are ignored, as the individual regression lines are fitted to the available longitudinal data, assuming at least two time points are available (for an accessible introduction see Hedeker, 2004). All participants attending at least two sessions were included in the sample. Non-inferiority analyses were conducted to examine whether both the CBT mean slope and session 12 intercept (and 95% CI around each parameter) differ by more than 0.6 SD from that of the RLX condition.

Analysis of therapist and patient ratings of anxiety was conducted using Analysis of Variance, as opposed to an MRM model, as nested group correlations were small and the design effects (1.01 to 1.31) were well below the 2.0 threshold reported by Muthén and Satorra (1995) as indicative of needing to be modeled. Independent blind assessors rated both the severity of primary diagnoses (CSR) and provided an overall assessment of patient severity (CGI), while clients completed a battery of self-report questionnaires. Variables were analyzed using between groups ANOVAs (RLX vs. CBT) with pre-treatment scores as covariates. Mean differences and 95% CI were then examined to see if they fell within 0.6 SD of the RLX mean. Given the high rate of treatment discontinuation, as well as the fact that most dropouts and some treatment completers did not complete all assessments, Intent-to-Treat analyses were conducted with the last data carried forward if no post-treatment data were available.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Of the randomization sample, 37 received a primary diagnosis of social anxiety disorder, 31 panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, 15 GAD, 2 anxiety disorder NOS, and one each of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and specific phobia. Over half (60.7%) of the sample were given one or more additional diagnoses, based on lower CSR scores, including major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or other depressive mood disorder (n = 28), GAD (n = 18), social anxiety disorder (n = 11), specific phobia (n = 8), panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (n = 8), obsessive-compulsive disorder (n = 7), body dysmorphic disorder (n = 4), substance abuse (n = 4), post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 2), adjustment disorder (n = 1), and trichotillomania (n = 1). Ignoring the hierarchy of principal versus comorbid diagnoses, 44.8% of the sample was diagnosed with panic disorder/agoraphobia, 55.2% with social anxiety disorder, 37.9% with GAD, 10.3% with a specific phobia, and 9.2% with OCD. Nearly a third (32.2%) of the sample had a comorbid depressive disorder diagnosis. Primary diagnosis2 was unrelated to pre-treatment Clinician Severity Ratings, F (2,76) = 0.08, p = .93, and number of sessions attended, F (5,81) = 0.83, p = .53.

Treatment fidelity

A Therapist Adherence Scale (available from the author) was developed based on a similar scale used by Ledley et al. (2009). Raters evaluated the extent to which several therapy components described in the treatment manual were implemented effectively. Ratings were performed on 20 randomly selected session video recording. Ratings were made on a 1-to-5 scale, ranging from 1 (ineffective) to 5 (extremely effective), with ratings of 4 (reasonably effective) or 5 (extremely effective) considered “within protocol”. Overall, raters judged the therapists to be consistent with the treatment protocols, achieving an average rating of 4.81 (SD=0.23). Furthermore, no single session was rated out of protocol.

Treatment credibility

Analysis of the Treatment Credibility Measure suggest that those in the CBT condition (M = 23.55, sd = 5.44) and those in the RLX condition (M = 22.56, sd = 4.60) did not differ significantly in their perceptions of treatment credibility, F(1,69) = 0.48, p = .49.

Attrition

Clients attended an average of 7.47 sessions (SD = 3.55), with a median of 9.00 and the modal number of sessions being 10. A non-significant trend was observed wherein participants in the CBT condition (M = 7.85, sd = 3.41) attended more sessions than did participants in the RLX condition (M = 6.36, sd = 3.81), F(1,85) = 2.93, p = .09. However, when examining rates of dropout, a greater proportion or participants receiving RLX (57.1%) than CBT (29.7%) discontinued treatment prematurely, χ2 (1, n=85) = 5.14, p = .023.

Primary Outcomes

Analyses of session-by-session change

To fully utilize the entire sample of treatment initiators, session-by-session STAI measures were examined using Mixed-effect Regression Modeling (MRM). Using a Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) estimator, the data were fitted to a random intercepts and slopes model with session-by-session STAI scores serving as a time variant regressor and condition as a time invariant factor. Data were nested within treatment groups to account for possible intraclass correlations due to nesting effects. Results indicated that the intercept of the STAI scores (i.e., prior to Session 1) were within the clinical range for both treatment conditions [CBT: Maximum Likelihood Estimate (MLE) = 48.88, Wald z = 45.00, p < .001; RLX: MLE = 46.30, Wald z = 40.28, p < .001], and similarly decreasing STAI scores were observed throughout treatment, (CBT: MLE = −1.12, Wald z = −8.33, p < .001; RLX: MLE = −1.19, Wald z = −6.70, p < .001). Non-inferiority analyses indicated that the confidence interval around the mean difference in slopes of STAI scores did not intersect 0.6 SD (MDiff = −0.015, 95% CI = −0.233 to 0.204, −0.6 SD = −.268), suggesting treatment equivalence.

Clinician measures

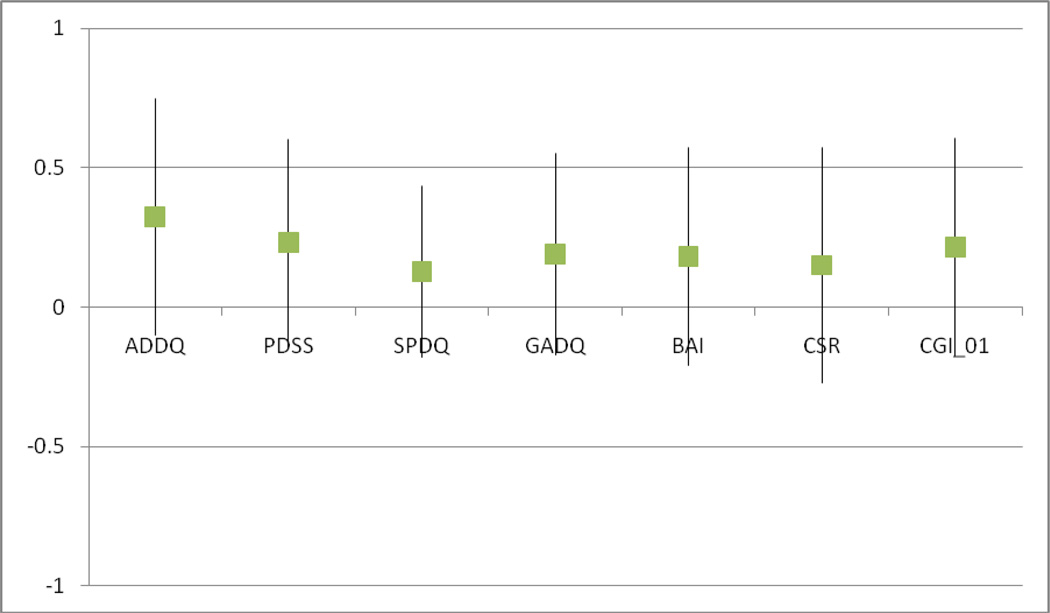

Independent assessors who were blind to treatment condition rated both the severity of primary diagnoses (CSR) and provided an overall assessment of patient severity (CGI). Both variables were analyzed using between-groups (Condition) ANOVAs with the respective pre-treatment score as a covariate. For primary diagnosis CSR, no effect of Condition was observed, F(1,80) = 1.20, p = .28, partial η2 = .015. Similarly, when examining overall CGI severity, no difference by Condition was found, F(1,67) = 0.51, p = .48, partial η2 = .008. Non-inferiority analyses indicated that the mean differences between conditions did not exceed Δ of 0.6 for CSR (MDiff = 0.199, 95% CI = −0.482 to 0.880, −0.6 SD = −1.275) and CGI scores (MDiff = 0.239, 95% CI = −0.434 to 0.912, −0.6 SD = −0.954) (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Mean difference (box) and 95% confidence intervals (whiskers) for outcome measures using intent-to-treat analyses. Note: All scores converted to Z distributions. Boxes above 0.00 represent superior mean outcome for CBT while boxes below 0.00 represent poorer mean outcome for CBT.

Self-report measures

Self-report measures were next analyzed using between-groups ANOVA with respective pre-treatment variables as covariates. For Intent-to-Treat (ITT) analyses carrying last available data forward, no differences by condition were observed on any measure, Fs = 0.70 – 2.31, ps = .17 – .41, partial η2s = .012 – 029 (see Table 1). As shown in Figure 2, none of the confidence intervals around the mean difference intersected Δ of −0.6 SD (Figure 2), indicating treatment equivalence.

Table 1.

Results from the 2 (Time) by 2 (Condition) ITT ANOVAs

| Post-Treatment Mean (SD) |

ANOVA (Condition) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | CBT (n = 65) | RLX (n = 22) | F | p | partial η2 |

| ADDQ | 27.07 (1.31) | 31.17 (2.36) | 2.31 | .17 | .029 |

| PDSS | 9.26 (0.57) | 10.80 (1.09) | 1.56 | .22 | .021 |

| SPDQ | 14.20 (0.61) | 15.23 (1.06) | 0.70 | .41 | .013 |

| GADQ | 18.46 (0.87) | 20.43 (1.65) | 1.12 | .30 | .015 |

| BAI | 20.10 (1.42) | 22.94 (2.71) | 0.86 | .36 | .012 |

Notes: Value represent estimated marginal means after controlling for pre-treatment scores.

ADDQ: Anxiety Disorder Diagnostic Questionnaire; PDSS: Panic Disorder Severity Scale; SPDQ: Social Phobia Diagnostic Questionnaire; GADQ: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire for DSM-IV; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory.

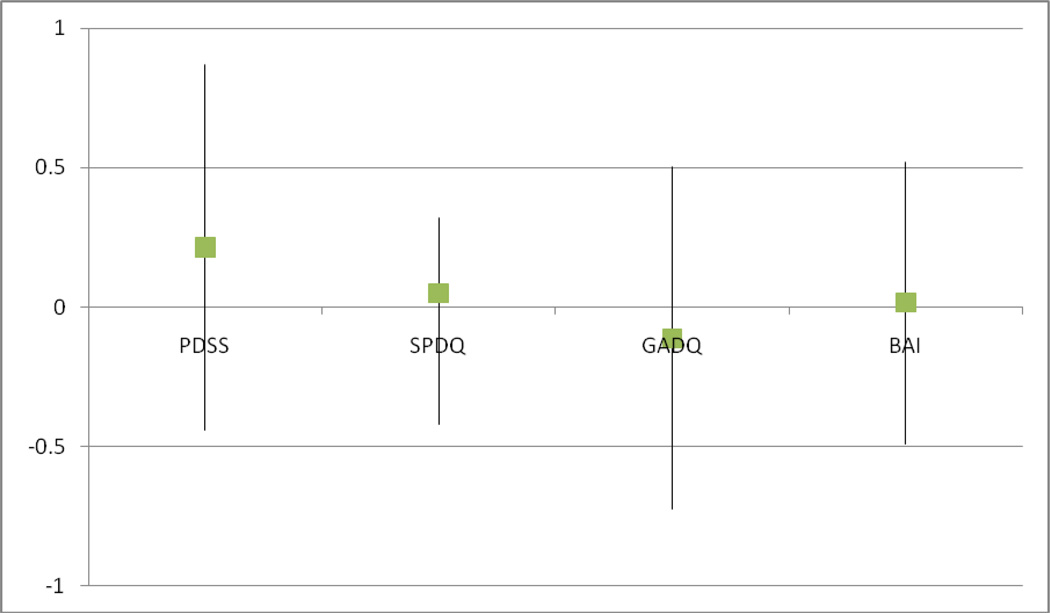

Given that ITT analyses can artificially increase the perception of treatment equivalence/non-inferiority, the self-report data were re-analyzed carrying forward data only if the participant completed the mid-treatment assessment3. These analyses (n CBT = 41, n RLX = 8) showed no significant differences in outcome by Condition, Fs < 0.01 – 0.43, ps = .51 – .95, partial η2s < .001 – .009. Non-inferiority analyses revealed that PDSS, SPDQ, and BAI were equivalent across conditions, while GADQ scores yielded inconclusive results as the 95% CI of the mean difference intersected Δ of −0.6 SD (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Mean difference (box) and 95% confidence intervals (whiskers) for outcome measures using partial (mid-treatment) data carried forward analyses. Note: All scores converted to Z distributions. Boxes above 0.00 represent superior mean outcome for CBT while boxes below 0.00 represent poorer mean outcome for CBT.

Transdiagnostic CBT and Diagnosis

To test the secondary hypothesis that transdiagnostic CBT would not differentially impact participants with varied diagnoses, primary diagnosis was entered into the previous models. As anxiety disorder NOS, specific phobia, and OCD were under-represented in this sample, the subsequent analyses were restricted to participants with primary diagnoses of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and GAD. Modeling of STAI scores yielded similar slope parameters for participants with panic disorder (MLE = −1.22, Wald z = −4.39, p < .001), social anxiety disorder (MLE = −1.02, Wald z = −5.44, p < .001), and GAD (MLE = −1.21, Wald z = − 2.59, p < .001). Constraining slope parameters to be equal improved overall fit (BICFreely Estimated = 3502.77, BICInvariant Slope = 3501.27), suggesting that slopes are invariant across primary diagnoses. Within the ANOVA models, primary diagnosis was unrelated to improvement during CBT across clinician rated measures, ps > .55, or self-reported measures, ps > .07.

Discussion

Transdiagnostic models and treatments appear to be gaining interest for anxiety disorders (Erickson et al., 2007; Norton, 2008; Schmidt et al., this issue), eating disorders (Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, 2003), and, more generally, negative affective syndromes (Barlow, Allen, & Choate, 2004; McEvoy & Nathan, 2007). Data published thus far suggests considerable improvement among those receiving transdiagnostic CBT for anxiety, and comparisons of effect sizes to those obtained from other treatment trials suggests that the improvement is similar to that seen in diagnosis-specific treatments (McEvoy & Nathan, 2007). Despite this, no published randomized clinical trials have directly compared the efficacy of transdiagnostic CBT to other established treatment conditions. As a result, the current study was designed to compare the efficacy of a transdiagnostic CBT treatment for anxiety disorders to a comprehensive relaxation training program.

Data were obtained from 87 treatment initiators randomly assigned to either a transdiagnostic group CBT or a comprehensive relaxation training program. The primary aim of the study was to compare efficacy and, consistent with hypothesis, results generally converged on the conclusion that transdiagnostic CBT and RLX showed statistically equivalent and significant efficacy. Evidence of at least equal efficacy was observed across clinician-rated measures, session-by-session self-report measures, as well as self-reported assessments completed both at pre- and post-treatment. Computation of an effect size estimate from the session-by-session measures (d = 1.43) suggests that the transdiagnostic CBT had an effect that is similar to average effects from diagnosis-specific CBT protocols (d = 1.58; Norton & Price, 2007), and consistent with previous trials of this protocol (Norton & Hope, 2005; Norton, 2008).

A secondary aim of the study was to examine differential efficacy of the transdiagnostic CBT by primary and comorbid diagnosis. Consistent with the hypothesis, no evidence of differential efficacy of the transdiagnostic CBT intervention was observed across diagnoses. This lack of differential effects by diagnosis is consistent with transdiagnostic models of anxiety (Barlow, 2000; Norton, 2006) and previous data reported by Norton (2008). The current study was not designed to compare outcomes in RLX by diagnosis, and was therefore not powered to evaluate the differential efficacy of relaxation training.

Together, the results of the study provide additional support for the efficacy of transdiagnostic anxiety treatments, as it showed effects at least as strong as another established treatment model, and demonstrated much lower rates of attrition. Even so, additional research into the long term comparative efficacy at follow-up, as well as the impact of targeting established risk variables in CBT but not RLX on relapse and return of fear is necessary. While steps were taken to maximize the validity of the current trial, several limitations must be considered. First, no “attention placebo” condition was implemented. It, therefore, cannot be ruled out that the equivalence in outcome between the two treatment conditions arose due to common factors. Given the high effect sizes, well-documented superiority of cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders over most other treatment approaches, and the established efficacy of relaxation training for many anxiety disorders, this appears unlikely. Even so, future studies of transdiagnostic anxiety treatments should consider the inclusion of an “attention placebo” or “nonspecific” treatment condition to examine explore the specific and non-specific contributions to anxiety reduction.

Second, although clinician-rated measurements such as the ADIS or CGI are commonly seen as the gold-standard for assessing outcomes, they, like self-report instruments, are based in part on the client’s description of their symptoms and distress. Behavioral or cognitive assessments, such as a behavioral approach test or the emotional Stroop test, respectively, would provide ideal corroborating evidence. However, given the heterogeneity of specific fears in transdiagnostic treatments, development of a test that is not differentially sensitive would be extremely difficult. That is, there is no evidence that behavioral approach tests of a 3-minute speech or approaching a spider would be psychometrically equivalent. Even so, future trials examining transdiagnostic treatments should strive to obtain evidence of treatment efficacy that does not rely solely on client report and clinician judgment.

A third limitation of the study was the limited profile of primary diagnoses in the current sample. Despite advertisement and recruitment efforts to obtain a diagnostically-diverse sample of individuals with anxiety disorders, nearly all of the sample had primary diagnoses of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder. While specific phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder were represented among comorbid diagnoses, and no evidence was observed suggesting differential efficacy based on these diagnoses, care should be taken in generalizing these results to individuals with primary diagnoses of OCD, PTSD, and specific phobias.

Finally, rates of attrition in the current study were high for a clinical trial, particularly in the RLX condition (57.1%). No explanation for this level of attrition is available, although it does not appear that participants discontinued due to symptom relief as those discontinuing from RLX still showed elevated STAI scores from their final attended session (M = 42.17, sd = 16.21). Attrition in the transdiagnostic CBT condition (29.7%) was also high, although not incongruent with other transdiagnostic treatments using similar broad inclusion criteria (e.g., 31% in Erickson et al., 2007; 40% in McEvoy & Nathan, 2007). Similarly, those who discontinued CBT also had high STAI scores from their last attended session (M = 50.79, sd = 12.37) suggesting they did not discontinue due to symptom remission either.

Limitations aside, the results of this study add to a growing evidence based supporting the efficacy of transdiagnostic CBT for anxiety disorders. Most previous trials have used no controls (Erickson, 2003; Norton, 2008), no-treatment or delayed-treatment controls (Erickson et al., 2007; Norton & Hope, 2005), or benchmarking strategies (McEvoy & Nathan, 2007) to establish efficacy. The current study is the first to incorporate an active treatment comparison condition: a comprehensive relaxation training program. Given that efficacy was at least equivalent to RLX, equivalent credibility, lack of differential efficacy by diagnosis, and lower rates of discontinuation, continued investigation and utilization of transdiagnostic anxiety treatments appears warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an NIMH Mentored Research Scientist Development Award (1K01MH073920).

Appendix A

CONSORT Checklist.

|

PAPER SECTION And topic |

Item | Descriptor | Reported on Page # |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE & ABSTRACT | 1 | How participants were allocated to interventions | 1, 2 |

|

INTRODUCTION Background |

2 | Scientific background and explanation of rationale. | 3–9, 12 |

|

METHODS Participants |

3 | Eligibility criteria for participants and the settings and locations where the data were collected. | 9,10 |

| Interventions | 4 | Precise details of the interventions intended for each group and how and when they were actually administered. | 13–14 |

| Objectives | 5 | Specific objectives and hypotheses. | 8–9 |

| Outcomes | 6 | Clearly defined primary and secondary outcome measures and, when applicable, any methods used to enhance the quality of measurements | 10–12 |

| Sample size | 7 | How sample size was determined and, when applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping rules. | 9–10 |

| Randomization -- Sequence generation | 8 | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence, including details of any restrictions | 10 |

| Randomization -- Allocation concealment | 9 | Method used to implement the random allocation sequence | 10 |

| Randomization -- Implementation | 10 | Who generated the allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to their groups. | 10 |

| Blinding (masking) | 11 | Whether or not participants, those administering the interventions, and those assessing the outcomes were blinded to group assignment. If done, how the success of blinding was evaluated. | 13,18 |

| Statistical methods | 12 | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary outcome(s); Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses. | 15–16 |

|

RESULTS Participant flow |

13 | Flow of participants through each stage Describe protocol deviations from study as planned, together with reasons. | 9–10,36 |

| Recruitment | 14 | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up. | 9 |

| Baseline data | 15 | Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of each group. | 9–10, 17 |

| Numbers analyzed | 16 | Number of participants (denominator) in each group included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by "intention-to-treat". | 9–10, 15–16 |

| Outcomes and estimation | 17 | For each primary and secondary outcome, a summary of results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision | 18–21 |

| Ancillary analyses | 18 | Address multiplicity by reporting any other analyses performed | 17, 20–21 |

| Adverse events | 19 | All important adverse events or side effects in each intervention group. | n/a |

|

DISCUSSION Interpretation |

20 | Interpretation of the results | 21–24 |

| Generalizability | 21 | Generalizability (external validity) of the trial findings. | 24 |

| Overall evidence | 22 | General interpretation of the results in the context of current evidence. | 21–24 |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of the University of Houston Moores School of Music, bass-baritone Timothy Jones, DMA, and Reynaldo Ochoa, DMA, in producing the relaxation CD used in this study.

Due to the limited representation of primary OCD, anxiety disorder NOS, PTSD, and specific phobia in the current sample, only participants with primary diagnoses of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and GAD were compared in these analyses by diagnosis.

The mid-treatment assessment did not include the ADDQ or any clinician-rated measures; these measures are, therefore, not presented.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. revised. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Crino R, Hunt C, Lampe L, Page A. The treatment of anxiety disorders. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Antony MM, Orsillo SM, Roemer L. Practitioner's guide to empirically based measures of anxiety. New York: Plenum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arntz A. Cognitive therapy versus applied relaxation as treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:633–646. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Unraveling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory. American Psychologist. 2000;55:1247–1263. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.11.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JG, Stanley MA, Baldwin LE, Deagle EA, III, Averill PM. Comparison of cognitive therapy and relaxation training for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:818–826. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DA, Borkovec TD. Progressive relaxation training: A manual for the helping profession. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Abel JA, Newman H. Effects of psychotherapy on comorbid conditions in generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:479–483. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;59:333–340. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Newman MG, Pincus A, Lytle R. A component analysis of cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder and the role of interpersonal problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:288–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Antony MM, Barlow DH. Diagnostic comorbidity in panic disorder: Effect on treatment outcome and course of comorbid diagnoses following treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:408–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:585–599. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Barlow DH. Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV (Adult Version) Albany, NY: Graywind; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler G, Cullington A, Munby M, Amies P, Gelder M. Exposure and anxiety management in the treatment of social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:642–650. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.4.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124:3–21. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A, Middleton H, Anastasaides P, Gelder M. A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation, and imipramine in panic disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;164:759–769. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Antony MM, Barlow DH. Mastery of your specific phobia. Albany, New York: Graywind; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of your anxiety and panic. New York: Oxford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Barlow DH, Zinbarg RE. Mastery of your anxiety and worry. Albany, NY: Graywind; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Rowe M, Lewin M, Noriega-Dimitri R. Interoceptive exposure versus breathing retraining within cognitive behavioural therapy for panic disorder with agoraphobia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1997;36:85–99. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruiter C, Ryken H, Garssen B, Kraaimaat F. Breathing retraining, exposure and a combination of both, in the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1989;27:647–655. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson DH. Group cognitive behavioural therapy for heterogeneous anxiety disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2003;32:179–186. doi: 10.1080/16506070310001686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson DH, Janeck A, Tallman K. Group cognitive-behavioral group for patients with various anxiety disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1205–1211. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:509–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;21:311–324. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PL, Durham RC. Recovery rates in generalized anxiety disorder following psychological therapy: An analysis of clinically significant change in the STAIT across outcome studies since 1999. Psychological Medicine. 1990;29:1425–1434. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Mastery of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Albany: Graywind; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Dancu CV, Hembree EA, Jaycox LH, Meadows EA, Street GP. A comparison of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training, and their combination for reducing posttraumatic stress disorder in female assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:194–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greist JH, Marks IM, Baer L, Kobak KA, Wenzel KW, Hirsch J. Behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder guided by a computer or by a clinician compared with relaxation as a control. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63:138–145. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D. An introduction to growth modeling. In: Kaplan D, editor. The Sage Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 215–234. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Dodge CS, Hope DA, Kennedy CR, Zollo LJ, Becker RE. Cognitive behavioral group treatment for social phobia: Comparison with a credible placebo. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Smits JAJ. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:621–632. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Juster H, Turk CL. Managing social anxiety and social phobia. Albany, NY: Graywind; 2000. (Client Manual). [Google Scholar]

- Jang KL. The behavioral genetics of psychopathology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jerremalm A, Jansson L, Öst L-G. Cognitive and physiological reactivity and the effects of different behavioral methods in the treatment of social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:171–180. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC. Coping Cat workbook. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ledley DR, Heimberg RG, Hope DA, Hayes SA, Zaider TI, Van Dyke M, Turk CL, Kraus C, Fresco DM. Efficacy of a manualized and workbook-driven individual treatment for social anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2009;40:414–424. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin PW, Silverman WK, Weems CF, Markham MR, Kurtines WM. Treating a heterogeneous set of anxiety disorders in youth with group cognitive behavioral therapy: A partially nonconcurrent multiple-baseline evaluation. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33:163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Marks I, Lovell K, Noshirvani H, Livanou M, Thrasher S. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder by exposure and/or cognitive restructuring. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:317–325. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Nathan P. Effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for diagnostically heterogeneous groups: A benchmarking study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:344–350. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Nathan P, Norton PJ. Efficacy of transdiagnostic treatments: A review of published outcome studies and future research directions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Moses EB, Barlow DH. A new unified treatment approach for emotional disorders based on emotion science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. In: Marsden P, editor. Sociological Methodology. Vol. 1995. 1995. pp. 216–316. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Clinical global impressions scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:839–843. [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Kachin KE, Zuellig AR, Constantino MJ, Cashman L. The social phobia diagnostic questionnaire: Preliminary validation of a new self-report diagnostic measure of social phobia. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:623–635. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ. An open trial of a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral group therapy for anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ. Toward a clinically-oriented model of anxiety disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2006;35:88–105. doi: 10.1080/16506070500441561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Hayes SA, Hope DA. Effects of a transdiagnostic group treatment for anxiety on secondary depressive disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;20:198–202. doi: 10.1002/da.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Hope DA. The “Anxiety Treatment Protocol”: A Group Case Study Demonstration of a Transdiagnostic Group CBT for Anxiety Disorders. Clinical Case Studies. 2008;7:538–554. [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Hope DA. Preliminary evaluation of a broad-spectrum cognitive-behavioral group therapy for anxiety. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2005;36:79–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Hope DA. Anxiety treatment program: Therapist manual. 2002 Unpublished treatment manual. [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Philipp LM. Transdiagnostic approaches to the treatment of anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, and Training. 2008;45:214–226. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Price EP. A meta-analytic review of cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome across the anxiety disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:521–531. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253843.70149.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Robinson CM. Development and evaluation of the Anxiety Disorder Diagnostic Questionnaire. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2010;39:137–149. doi: 10.1080/16506070903140430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst LG, Westling BE. Applied relaxation vs. cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:145–158. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)e0026-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst LG, Westling BE, Hellstrom K. Applied relaxation, exposure in vivo and cognitive methods in the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31:383–394. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90095-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson R. Changeways: Relaxation programme. Vancouver, BC: Changeways Clinic; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Persons JB, Tompkins MA. Cognitive-behavioral case formulation. In: Eels TD, editor. Handbook of psychotherapy case formulation. New York: Guilford; 1997. pp. 314–339. [Google Scholar]

- Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJW. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: An extension of the CONSORT statement. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1152–1160. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims: A treatment manual. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Borkovec M, Posa S, Borkovec TD. A self-report diagnostic measure of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1995;26:345–350. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(95)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Buckner JD, Pusser A, Woolaway-Bickel K, Preston JL. Randomized controlled trial of False Safety Behavior Elimination Therapy (F-SET): A unified cognitive behavioral treatment for anxiety psychopathology. Behavior Therapy. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.02.004. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Woolaway-Bickel K, Trakowski J, Santiago H, Storey J, Koselka M, Cook J. Dismantling cognitive-behavioral treatment for panic disorder: Questioning the utility of breathing retraining. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psycholology. 2000;68:417–424. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, Gorman JM, Papp LA. Multicenter Collaborative Panic Disorder Severity Scale. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1571–1575. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Luschene RE, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for adults. Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer PJ, Seivewright N, Murphys S, Ferguson B, Kingdon D, Barczak B, et al. The Nottingham study of neurotic disorder: Comparison of drug and psychological treatments. Lancet. 1988;2:235–240. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens BL. Choosing an equivalence limit for noninferiority or equivalence studies. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2002;23:2–4. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Horowitz JD, Powers MB, Telch MJ. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1021–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollo L, Dodge C, Kennedy C, Heimberg R, Becker R. Treatment of social phobia: A manual for the conduct of educational-supportive psychotherapy groups. (unpublished). Unpublished treatment manual. [Google Scholar]