Abstract

The present study was undertaken to determine the anticancer efficacy of zerumbone (ZER), a sesquiterpene from subtropical ginger, against human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. ZER treatment caused a dose-dependent decrease in viability of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells in association with G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction. ZER-mediated cell cycle arrest was associated with downregulation of cyclin B1, cyclin-dependent kinase 1, Cdc25C, and Cdc25B. Even though ZER treatment caused stabilization of p53 and induction of PUMA, these proteins were dispensable for ZER-induced cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis. Exposure of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells to ZER resulted in downregulation of Bcl-2 but its ectopic expression failed to confer protection against ZER-induced apoptosis. On the other hand, the SV40 immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts derived from Bax and Bak double knockout mice were significantly more resistant to ZER-induced apoptosis. ZER-treated MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells exhibited a robust activation of both Bax and Bak. In vivo growth of orthotopic MDA-MB-231 xenografts was significantly retarded by ZER administration in association with apoptosis induction and suppression of cell proliferation (Ki-67 expression). These results indicate that ZER causes G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and Bax/Bak-mediated apoptosis in human breast cancer cells, and retards growth of MDA-MB-231 xenografts in vivo.

Keywords: breast cancer, zerumbone, p53, PUMA, Bcl-2, Bax, Bak, apoptosis

Introduction

Breast cancer is a major health problem for women worldwide [1] necessitating identification of novel anticancer strategies. Merit of this objective is further enforced as many of the known risk factors associated with breast cancer are not easily modifiable (e.g., genetic predisposition) [2,3]. Dietary compounds owing to their safety have drawn considerable attention in recent years for the discovery of novel cancer preventive and therapeutic agents [4]. Bioactive compounds with preventive efficacy against cancer in preclinical rodent models have now been identified from many edible vegetables, including cruciferous vegetables (e.g., watercress and broccoli) and garlic [4–8]. Moreover, population-based case-control studies continue to support the notion that dietary intake of certain fruits and vegetables may reduce the risk of cancer [9–11].

Zerumbone (2,6,9,9-tetramethylcycloundeca-2,6,10-trien-1-one; hereafter abbreviated as ZER), a monocyclic sesquiterpene derived from tropical ginger Zingiber zerumbet, is one such phytochemical with preventive efficacy in preclinical rodent models of cancer and pancreatitis [12–17]. For example, dietary administration of ZER for 5 weeks caused reduction in the frequency of aberrant crypt foci in association with suppression of cyclooxygenase-2 [12]. Oral feeding of ZER inhibited dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in female ICR mice [13]. ZER treatment was also reported to suppress skin tumor initiation and promotion in ICR mice [14]. ZER administration caused regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in female Balb/c mice prenatally exposed to diethylstilboestrol [18]. Diethylnitrosamine-initiated and 2-acetylaminofluorene-promoted liver carcinogenesis was inhibited by treatment with ZER [19].

Cell culture models have also been used to study anticancer effects of ZER [20–26]. For example, ZER inhibited proliferation of human colonic adenocarcinoma cell lines in association with dysfunction of mitochondria transmembrane leading to apoptotic cell death [20]. Cytotoxic effect of ZER on leukemia cells was found to be mediated through cell cycle arrest and Fas- and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis [21]. In liver cancer HepG2 cells, ZER-induced apoptosis was shown to be independent of p53 but associated with modulation of Bax/Bcl-2 ratio [22]. Despite these advances, however, the mechanisms underlying growth inhibitory and proapoptotic effect of ZER are not fully understood. In the present study, we have addressed this mechanistic gap using MDA-MB-231 (an estrogen-independent cell line with mutant p53) and MCF-7 (an estrogen responsive cell line with wild-type p53) human breast cancer cells as a model.

Materials and methods

Ethics Statement

Use of mice for the studies described herein was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number-1004983).

Reagents

ZER was either purified as described previously [27] or purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Reagents including 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and propidium iodide (PI) were from Sigma-Aldrich, whereas cell culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen-Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Sources of antibodies were as follows: antibodies against Cdc25C, cleaved poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerase (PARP), and p53 were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); anti-cyclin B1, anti-cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1), anti-Bak, anti-Bax, and anti-p53 upregulated mediator of apoptosis (PUMA) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); antibodies against Cdc25B and active Bax (for immunofluorescence microscopy) were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA); anti-Bcl-2 antibody was from Dako-Agilent Technologies (Houston, TX); an antibody specific for detection of active Bak (for immunofluorescence microscopy) was from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA); and anti-actin antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich. MitoTracker Green and Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies were from Invitrogen-Life Technologies. Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection kit was purchased from BD Biosciences. The p53-targeted small interfering RNA (siRNA) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, whereas a control nonspecific siRNA was purchased from Qiagen (Germantown, MD).

Cell lines, cell survival assay, and analysis of cell cycle distribution

MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and MCF-10A cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained as described by us previously [28]. Wild-type HCT-116 cell line and its isogenic PUMA knockout variant were generously provided by Dr. Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) and cultured in McCoy's 5A modified medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) derived from wild-type (WT) and Bax and Bak double knockout (DKO) mice and immortalized by transfection with a plasmid containing SV40 genomic DNA were generously provided by the late Dr. Stanley J. Korsmeyer (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) and maintained as described previously [29]. Stock solution of ZER was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and diluted with complete media before use. An equal volume of DMSO (final concentration 0.1%) was added to controls. Effect of ZER treatment on cell survival was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion assay as described by us previously [30] or cell proliferation assay using a Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Effect of ZER treatment on cell cycle distribution was determined by flow cytometry after staining the cells with PI as described by us previously [31].

Western blotting

Control and ZER-treated cells were processed for immunoblotting as described by us previously [28–32]. Densitometric quantitation was done using UN-SCAN-IT software version 5.1 (Silk Scientific Corporation, Orem, Utah).

Apoptosis assays

Apoptosis induction was assessed by quantitation of histone-associated DNA fragment release into the cytosol using an ELISA kit from Roche Applied Sciences (Indianapolis, IN) or flow cytometry using Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection kit.

RNA interference

MCF-7 (1.5×105) cells were seeded in six-well plates and transfected at ~50% confluency with 100 nM of p53-targeted siRNA or control siRNA using Oligofectamine. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO (control) or ZER (20 µM) for 24 hours. Cells were collected and processed for western blotting and determination of cell cycle distribution.

Ectopic expression of Bcl-2 by transient transfection

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected at ~50–60% confluency with the empty pSFFV-neo vector or pSFFV vector encoding for Bcl-2 using FuGENE6 transfection reagent. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO or ZER and processed for immunoblotting and measurement of apoptosis and cell viability.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

Effect of ZER on mitochondrial membrane potential was measured using potential-sensitive dye JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions [33].

Immunocytochemical analysis for active Bax and active Bak

MDA-MB-231 or MCF-7 cells (2.5×104 cells/mL) were cultured on coverslips, allowed to attach, and then exposed to DMSO (control) or 20 µM ZER for 8 hours. Immunocytochemical analysis for active Bak and active Bax was performed as described by us previously [29]. The cells were examined under a Leica DC300F microscope at 100× magnification.

Orthotopic xenograft study

Female severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and acclimated for 1 week prior to the start of the experiment. Following 1 week feeding of irradiated AIN-76A diet (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI), exponentially growing MDA-MB231-luc-D3H1 cells (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) were suspended in media and mixed in a 1:1 ratio with Matrigel. A 0.03 mL suspension containing 2.5×106 cells was injected orthotopically in both inguinal mammary fat pads. On the same day, the mice began intraperitoneal administration of either PBS (100 µL) or ZER (0.18 or 0.35 mg ZER/mouse; equates to about 7.5 and 15.7 mg ZER/kg body weight, respectively, in 100 µL PBS) five times/week (Monday through Friday). At the onset of the study, there were 10 mice in each group. Number of effective mice at the conclusion of the study was n=6 for the control group and 0.18 mg ZER/mouse groups and n=7 for the 0.35 mg ZER/mouse group because of premature deaths unrelated to treatment and/or failure of tumor take. In the 0.35 mg ZER/mouse group, tumor grew only on one flank in two mice. Body weights of the mice were recorded weekly.

Detection of apoptotic bodies by TUNEL assay and immunohistochemistry for Ki-67

A portion of the tumor tissue was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4–5 µm thickness. TUNEL staining and immunohistochemical analysis for Ki-67 expression was performed as described by us previously [5–8].

Results

ZER inhibited viability of cultured human breast cancer cells by causing growth arrest

Structure of ZER is shown in Fig. 1a. Viability of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells was decreased significantly upon treatment with ZER in a concentration and time-dependent manner as evidenced by trypan blue dye exclusion assay (Fig. 1b) and cell proliferation assay (results not shown). For example, the IC50 for ZER in MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 hour and 48 hour exposure was 9.9 ± 4.9 µM and 4.2 ± 1.2 µM (n=3), respectively. The IC50 for ZER in MCF-7 cells after 24 hour and 48 hour treatment was 10.1 ± 5.3 and 2.9 ± 0.8 µM (n=3), respectively. Exposure of MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 1c) and MCF-7 cells (results not shown) to ZER resulted in an increase in sub-diploid (indicative of apoptosis) and G2/M fraction that was accompanied by a reduction in G0G1 phase and S phase cells compared with DMSO-treated control. The G2/M phase cell cycle arrest resulting from ZER treatment was maintained when the cells were cultured for an additional 24 hours in the absence of the drug (results not shown). The ZER-induced G2/M phase cell cycle arrest was associated with a marked decrease in protein levels of cyclin B1, Cdk1, Cdc25C, and Cdc25B in both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Zerumbone (ZER) inhibits survival of cultured human breast cancer cells. a Structure of ZER. b Effect of ZER on survival of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells as determined by trypan blue exclusion assay. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). *Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with DMSO-treated control by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. c Cell cycle distribution in MDA-MB-231 cultures after 24 hour treatment with DMSO (control) or the indicated concentrations of ZER. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). *Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with DMSO-treated control by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. d Immunoblotting for cyclin B1, Cdk1, Cdc25C, and Cdc25B using lysates from MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells treated with DMSO or the indicated concentrations of ZER. The blots were re-probed with anti-actin antibody as a loading control. Numbers on top of the immunoreactive bands represent changes in protein levels relative to corresponding DMSO-treated control. Each experiment was performed at least twice and the results were consistent.

ZER caused apoptosis in human breast cancer cells

Fig. 2a shows representative flow histograms for Annexin V-FITC-positive and PI-negative (early apoptotic cells) and Annexin V-FITC-positive and PI-positive (late apoptotic cells) fraction in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cultures treated for 48 hours with DMSO or ZER. Fraction of apoptotic cells was increased markedly upon treatment with ZER (Fig. 2b). Consistent with these results, the ZER-treated MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (24 hour treatment) exhibited a dose-dependent and statistically significant increase in histone-associated DNA fragment release into the cytosol compared with corresponding DMSO-treated controls (Fig. 2c). Finally, apoptosis induction by ZER in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells was confirmed by immunoblotting for cleaved PARP (Fig. 2d). In contrast to MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, ZER treatment (5–50 µM for 24 hours) failed to induce histone-associated DNA fragment release into the cytosol in MCF-10A cells (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicated that breast cancer cells were more sensitive to ZER mediated apoptosis compared with normal cells.

Fig. 2.

Zerumbone (ZER) treatment caused apoptotic cell death in cultured human breast cancer cells. a Representative flow histograms depicting apoptotic fraction (Annexin V-FITC/PI method) in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells treated for 48 hours with DMSO (control) or 40 µM of ZER. b Quantitation of apoptotic fraction (early + late apoptotic cells) enrichment relative to DMSO-treated control in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells treated for 24 or 48 hours with the indicated concentrations of ZER. c Quantitation of histone-associated DNA fragment release into the cytosol in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells treated for 24 hours with DMSO (control) or the indicated concentrations of ZER. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). *Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with DMSO-treated control by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. d Immunoblotting for PARP cleavage using lysates from MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells after 24 or 36 hour treatment with DMSO or ZER (20 or 40 µM). The blots were re-probed with anti-actin antibody as a loading control. Numbers on top of the immunoreactive bands represent changes in protein levels relative to corresponding DMSO-treated control. Each experiment was done at least twice and representative data from one such experiment are shown. The results in different experiments were consistent.

The p53 and PUMA proteins were dispensable for ZER-induced apoptosis

PUMA is a BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family of proapoptotic proteins that facilitates apoptosis by different stimuli [34]. There was a marked increase in the levels of PUMA protein after treatment with ZER in both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3a). Because PUMA is a p53 regulated protein, these results indicated that PUMA induction resulting from ZER treatment involved p53-independent mechanism(s). However, PUMA was dispensable for ZER-mediated apoptosis induction (Fig. 3b) as well as inhibition of cell proliferation (Fig. 3c) as evidenced by analysis in wild-type and PUMA knockout (KO) variants of HCT-116 cells. Likewise, even though ZER treatment resulted in stabilization of p53 protein in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3d), the ZER-induced enrichment of sub-diploid apoptotic fraction (Fig. 3e) as well as G2/M fraction (Fig. 3f) was sustained even after knockdown of the p53 protein by 60%. Based on these observations, we conclude that both p53 and PUMA proteins are dispensable for cellular responses to ZER.

Fig. 3.

p53 and PUMA are dispensable for zerumbone (ZER)-induced apoptosis. a Immunoblotting for PUMA (p53 upregulated mediator of apoptosis) using lysates from MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells after 24 or 36 hour treatment with DMSO or ZER (20 or 40 µM). The blots were re-probed with anti-actin antibody as a loading control. Numbers on top of the immunoreactive bands represent changes in protein levels relative to corresponding DMSO-treated control. b Quantitation of apoptotic fraction (early + late apoptotic cells) in wild-type HCT-116 cells (WT) and PUMA knockout HCT-116 cells (PUMA KO) following 48 hour treatment with DMSO or indicated concentrations of ZER. Quantitation relative to DMSO-treated WT HCT-116 cells is shown. c Effect of ZER treatment on proliferation of wild-type HCT-116 cells (WT) and PUMA knockout HCT-116 cells (PUMA KO) after 48 hour treatment with DMSO or the indicated concentrations of ZER as determined by cell proliferation assay. Quantitation relative to DMSO-treated WT HCT-116 cells is shown. In panels b and c, data represent mean ± SD (n=3). Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with respective to acorresponding DMSO-treated control and bbetween WT and PUMA KO HCT-116 cells by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. d Immunoblotting for p53 protein using lysates from MCF-7 cells transiently transfected with a nonspecific control siRNA and p53-targeted siRNA and treated for 24 hours with either DMSO (control) or 20 µM of ZER. Quantitation relative to control siRNA transfected cells treated with DMSO is shown above bands. Percentage of (e) sub G0G1 fraction and (f) G2/M fractions in MCF-7 cells transiently transfected with control siRNA and p53-targeted siRNA and treated for 24 hours with DMSO (control) or 20 µM of ZER. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). aSignificantly different (P<0.05) compared with DMSO-treated control by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. Each experiment was done at least twice and the results were consistent.

Bcl-2 overexpression failed to confer protection against ZER-induced apoptosis

Because ZER was previously shown to modulate levels of Bcl-2 protein in liver cancer cells [22], we determined its role in breast cancer cell apoptosis by ZER. As can be seen in Fig. 4a, ZER treatment (20 or 40 µM for 24 and 36 hours) resulted in a decrease in protein levels of Bcl-2 in both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells. Transient transfection of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells with Bcl-2 plasmid resulted in 25- and 2.2-fold increase in its protein level, respectively, compared with corresponding empty vector-transfected control cells (Fig. 4b). However, ectopic expression of Bcl-2 failed to abolish ZER-mediated cleavage of PARP (Fig. 4b), histone-associated DNA fragment release into the cytosol (Fig. 4c) or inhibition of cell survival (Fig. 4d). Even though % survival upon treatment with ZER in vector transfected control MDA-MB-231 cells appeared different from that in Bcl-2 overexpressing cells, the difference was not significant in any of the 3 independent experiments (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 4.

Bcl-2 overexpression failed to confer protection against zerumbone (ZER)-induced apoptosis. Immunoblotting for (a) Bcl-2 in control and ZER-treated MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells and (b) Bcl-2 and cleaved PARP in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells transiently transfected with pSFFV-neo empty vector or pSFFV vector encoding for Bcl-2 and treated for 24 hours with DMSO or the indicated concentrations of ZER. Numbers on top of the immunoreactive bands represent changes in protein levels relative to corresponding DMSO-treated control (panel a) or empty vector transfected cells treated with DMSO (panel b). c Quantitation of histone-associated DNA fragment release into the cytosol, and (d) cell survival in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells transiently transfected with empty vector or pSFFV vector encoding for Bcl-2 and treated for 24 hours with DMSO or the indicated concentrations of ZER. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). Quantitation relative to DMSO-treated empty vector transfected cells is shown. Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with arespective DMSO-treated control and bbetween empty vector transfected and Bcl-2 overexpressing cells by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. Each experiment was done at least twice and representative data from one such experiment are shown.

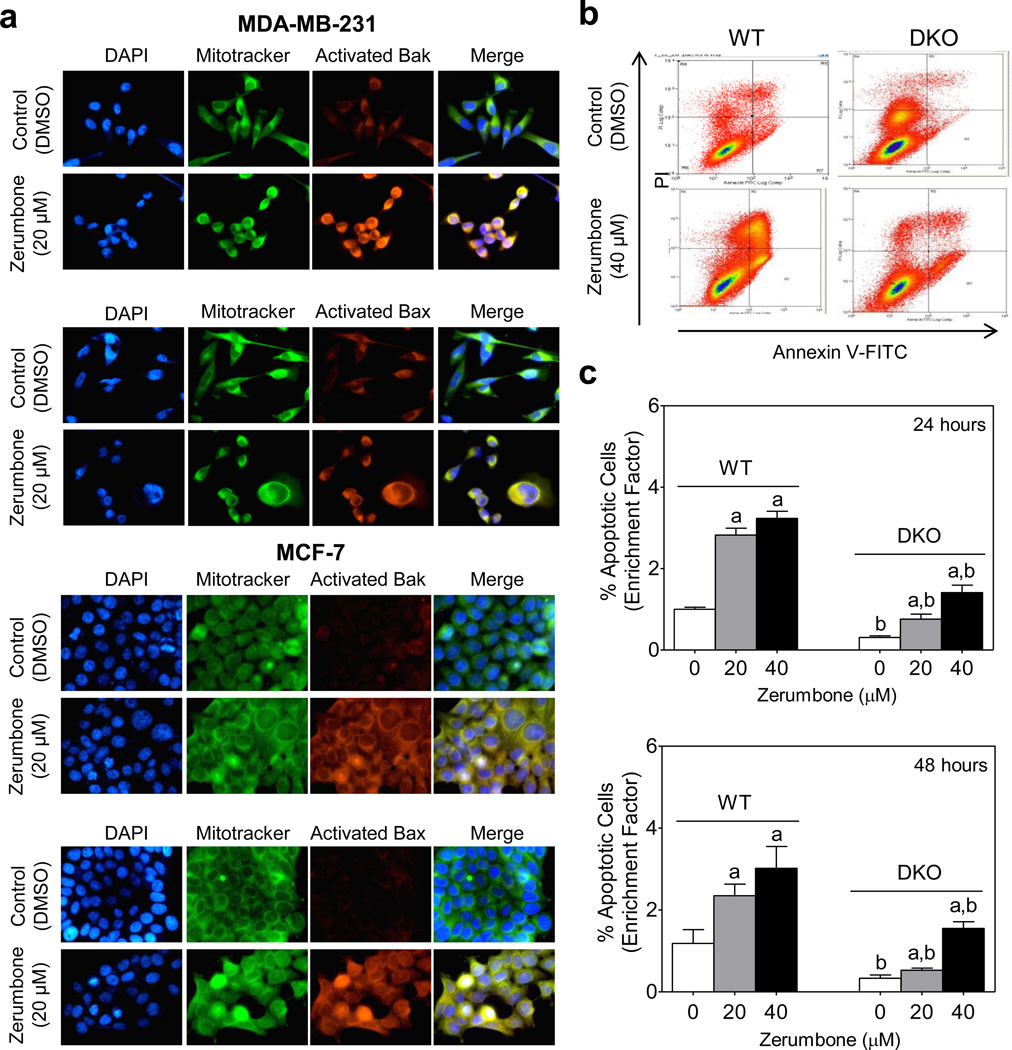

ZER-induced apoptosis was mediated by activation of Bax and Bak

We next studied potential involvement of multidomain proapoptotic proteins Bax and Bak in ZER-induced apoptosis. The protein levels of Bax and Bak were only modestly increased upon treatment of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells with ZER (Fig. 5a). Many apoptogenic signals promote conformational change (activation) of Bax and Bak which in turn causes their oligomerization to induce pores in the outer membrane resulting in a loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential followed by cell death [35,36]. As shown in Fig. 5b, ZER treatment caused collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential as evidenced by accumulation of monomeric JC-1 (green fluorescence). We performed immunocytochemistry to determine activation of Bax and Bak in cells treated with 20 µM of ZER (8 hours) using antibodies specific for detection of active Bax (6A7; BD Biosciences) and active Bak (AM03; Calbiochem). The ZER treatment caused activation of Bax and Bak in both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells as evidenced by merging of the Bax- or Bak-associated red fluorescence and MitoTracker Green-associated fluorescence leading to appearance of yellow-orange color, which was rare in DMSO-treated control cells (Fig. 6a). The ZER treated MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells also showed change in the appearance of mitochondrial network, as mitochondria that normally have an elongated structure acquired a rounded shape with closely packed stacks (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 5.

Zerumbone (ZER) causes collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential in breast cancer cells. a Immunoblotting for Bak and Bax using lysates from MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells after 24 or 36 hour treatment with DMSO or ZER (20 or 40 µM). Numbers on top of the immunoreactive bands represent changes in protein levels relative to corresponding DMSOtreated control. b Quantitation of monomeric JC-1-associated green fluorescence by flow cytometry in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells after 16 or 24 hour treatment with DMSO or ZER (20 or 40 µM). Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). *Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with DMSO-treated control by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. Each experiment was done at least twice and representative data from one such experiment are shown.

Fig. 6.

Critical role for Bax and Bak in zerumbone (ZER)-induced apoptosis. a Fluorescence microscopy for analysis of active Bax and Bak in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells after 8 hour treatment with DMSO or 20 µM of ZER. Staining for mitochondria (MitoTracker Green) and activated Bak or Bax is indicated by green and red colors, respectively. b Representative flow histograms depicting apoptotic fraction quantitation in SV40 immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) derived from wild-type mice (WT) and Bak and Bax double knockout (DKO) mice after 24 hour treatment with DMSO or indicated concentration of ZER. c Quantitation of apoptotic cells (Annexin V-FITC/PI method) in SV40 immortalized MEFs derived from wild type mice (WT) and Bak-Bax double knockout (DKO) mice. The MEF were treated for 24 or 48 hours with DMSO (control) or the indicated concentrations of ZER and processed for flow cytometry. Quantitation relative to DMSO-treated WT MEF is shown. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with arespective DMSO-treated control and bbetween WT and DKO by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. Each experiment was done at least twice and representative data from one such experiment are shown.

Contribution of Bax and Bak in apoptotic response to ZER was confirmed by comparing sensitivities of SV40 immortalized MEF derived from WT and DKO (Bax and Bak double knockout) mice. The ZER treatment (20 or 40 µM for 24 or 48 hours) caused a dose-dependent increase in the apoptotic cells in both WT and DKO MEF, but the apoptosis was significantly more pronounced in the WT MEF than in the DKO (Fig. 6b,c). Collectively, these results indicated that: (a) ZER treatment caused activation of both Bax and Bak, and (b) Bax and Bak deficiency conferred significant protection against ZER-induced apoptosis in immortalized MEF. The WT and DKO MEF is a better cellular model to test the role of Bax and Bak over RNA interference which often fails to produce complete knockdown if simultaneously attempted for more than one protein.

ZER administration inhibited growth of MDA-MB-231 xenografts

We determined the effect of ZER administration on growth of MDA-MB-231 cells implanted orthotopically in mammary fat pads of female SCID mice. The ZER concentrations used in the present study were within the range utilized in previous animal studies [18,19]. The initial and final body weights of the control and ZER-treated mice did not differ significantly (Fig. 7a). In this experiment, luciferase expressing MDA-MB-231 (clone Luc D3H1) cells were used with the intention to image the mice as well as to quantify bioluminescence. However, this was not possible because the number of effective mice was smaller than initially planned and due to variability inherent to bioluminescence (results not shown). Nevertheless, the average wet weight of the tumor after sacrifice of the animals was significantly lower in the 0.18 mg ZER/mouse group compared with control group (Fig. 7b). The difference between the control group and the 0.35 mg ZER/mouse group did not reach statistical significance due to large data scatter in the later. Nevertheless, these results demonstrated in vivo efficacy of ZER against MDA-MB-231 xenografts.

Fig. 7.

Zerumbone (ZER) administration inhibits growth of MDA-MB-231-luc-D3H1 cells in vivo. a Average initial and final body weight of the control and ZER treated mice. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=6 for the control and 0.18 mg/mouse groups and n=7 for the 0.35 mg/mouse group). b Tumor wet weight in control mice (n=12, six mice with tumors on both sides) and those treated with 0.18 mg ZER/mouse (n=12, six mice with tumors on both sides) and 0.35 mg ZER/mouse (n=12, even though there were 7 mice in this group, the tumors in two mice grew only on one side). Results shown are mean ± SD. *Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with control by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. c TUNEL-positive apoptotic bodies in representative tumor section of a control mouse and a mouse of the 0.35 mg/mouse group (×200 magnification). Results shown are mean (n=7). *Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with control by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. d Ki-67 expression in representative tumor section of a control mouse and a mouse of the 0.35 mg/mouse group (×200 magnification). Results shown are mean (n=7). *Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with control by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test.

ZER administration increased apoptosis and inhibited cell proliferation in the MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts

ZER administration resulted in a statistically significant increase in number of apoptotic bodies in the tumor as visualized by TUNEL assay (Fig. 7c). In addition, expression of proliferation marker Ki-67 [37] was significantly lower in the tumors of ZER-treated mice compared with those of control mice and the difference was significant at the 0.35 mg ZER/mouse group (Fig. 7d).

Discussion

Results presented herein indicate that ZER treatment inhibits survival of human breast cancer cells regardless of the estrogen responsiveness or the p53 status. Growth inhibitory effect of ZER is associated with cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction. Activity of ZER against breast cancer is not restricted to cultured cells as growth of MDA-MB-231 xenografts in vivo is significantly retarded by ZER administration. Consistent with cellular data, antitumor effect of ZER in vivo is accompanied by reduced cell proliferation as evidenced by Ki-67 expression and increased apoptosis. Moreover, ZER administration is well tolerated by the mice and does not cause weight loss or any other side effects. Prevention of induced cancers in rodents by ZER has been documented previously [12,14,16], but the present study is the first published report showing in vivo efficacy of this compound against transplanted breast cancer cells. These observations provide impetus for future in vivo evaluation of ZER for prevention of mammary cancer in preclinical models to justify its clinical investigation as a chemopreventive agent. In this context, it is important to mention that addition of a different variety of ginger (Z officinale) (1.5 g/d in three divided doses every 8 hours) to standard antiemetic therapy (granisetron plus dexamethasone) in patients with advanced breast cancer effectively reduces the prevalence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting [38]. In a phase II study, ginger root extract decreased eicosanoids in colon mucosa in people at normal risk for colorectal cancer [39].

The present study shows that breast cancer cells are arrested in G2/M phase of the cell cycle after treatment with ZER. While these observations are consistent with literature data showing G2/M phase cell cycle arrest in ZER-treated leukemia, ovarian and cervical cancer cells [15,25], our data also indicates that the cell cycle arrest resulting from ZER exposure is irreversible. The G2/M progression is regulated by a kinase complex consisting of cyclin B1 and Cdk1 [40] and ZER treatment down regulates both these proteins. Downregulation of cyclin B1 and Cdk1 upon treatment with ZER has also been observed in leukemia cells [15]. The Cdc25 family phosphatases play an important role in activation of the cyclin B1/Cdk1 complex. The ZER-treated cells exhibit a decrease in protein levels of both Cdc25B and Cdc25C (present study). However, the cell cycle arrest resulting from ZER treatment is not dependent on p53, which is a therapeutic advantage because this tumor suppressor is often mutated in human cancers including breast cancer [41].

The present study indicates that PUMA protein, which is involved in regulation of apoptosis by different stimuli including some natural products [34,42], is dispensable for apoptosis induction by ZER. Likewise, unlike certain other proapoptotic agents [30], Bcl-2 overexpression has no meaningful impact on ZER-induced apoptosis. We also demonstrate that ZER causes activation of Bax and Bak but has only modest effect on their protein levels. Effect of ZER on Bak level or activation has not been examined previously to the best of our knowledge, but in leukemia cells ZER treatment had no effect on Bax protein expression [21]. A critical role for Bax in apoptosis induction by ZER has been reported in human colon cancer cells [24]. The ZER-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells is associated with reactive oxygen species production [24]. Interestingly, examples exist to illustrate critical role of reactive oxygen species in Bax activation and apoptosis induction by some stimuli, including natural products phenethyl isothiocyanate (a constituent of watercress) and Withaferin A (a small molecule derived from a medicinal plant used in India) [43–45]. It is possible that Bax and Bak activation by ZER in breast cancer cells is linked to production of reactive oxygen species. Further work is needed to experimentally verify this possibility

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure:

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 CA142604-03 and RO1 CA129347-06 (to SVS). This research project used the Animal Facility and the Tissue and Research Pathology Facility that were supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health under award number P30 CA047904.

Abbreviations

- ZER

zerumbone

- DAPI

4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- PI

propidium iodide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- PUMA

p53 upregulated mediator of apoptosis

- PARP

poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- JC-1

5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

AS, JAA, AM, and SVS declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hulka BS, Moorman PG. Breast cancer: hormones and other risk factors. Maturitas. 2001;38:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelsey JL, Gammon MD, John EM. Reproductive factors and breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:36–47. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surh YJ. Cancer chemoprevention with dietary phytochemicals. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:768–780. doi: 10.1038/nrc1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh SV, Powolny AA, Stan SD, et al. Garlic constituent diallyl trisulfide prevents development of poorly differentiated prostate cancer and pulmonary metastasis multiplicity in TRAMP mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9503–9511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh SV, Warin R, Xiao D, Powolny AA, et al. Sulforaphane inhibits prostate carcinogenesis and pulmonary metastasis in TRAMP mice in association with increased cytotoxicity of natural killer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2117–2125. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powolny AA, Bommareddy A, Hahm ER, et al. Chemopreventative potential of the cruciferous vegetable constituent phenethyl isothiocyanate in a mouse model of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:571–584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh SV, Kim SH, Sehrawat A, et al. Biomarkers of phenethyl isothiocyanate-mediated mammary cancer chemoprevention in a clinically relevant mouse model. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1228–1239. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michaud DS, Spiegelman D, Clinton SK, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of bladder cancer in a male prospective cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:605–613. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen JH, Kristal AR, Stanford JL. Fruit and vegetable intakes and prostate cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:61–68. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowke JH, Chung FL, Jin F, et al. Urinary isothiocyanate levels, brassica, and human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3980–3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka T, Shimizu M, Kohno H, et al. Chemoprevention of azoxymethane-induced rat aberrant crypt foci by dietary zerumbone isolated from Zingiber zerumbet. Life Sci. 2001;69:1935–1945. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murakami A, Hayashi R, Tanaka T, et al. Suppression of dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice by zerumbone, a subtropical ginger sesquiterpene, and nimesulide: separately and in combination. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murakami A, Tanaka T, Lee JY, et al. Zerumbone, a sesquiterpene in subtropical ginger, suppresses skin tumor initiation and promotion stages in ICR mice. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:481–490. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang GC, Chien TY, Chen LG, Wang CC. Antitumor effects of zerumbone from Zingiber zerumbet in P-388D1 cells in vitro and in vivo. Planta Med. 2005;71:219–224. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim M, Miyamoto S, Yasui Y, et al. Zerumbone, a tropical ginger sesquiterpene, inhibits colon and lung carcinogenesis in mice. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:264–271. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabolcs A, Tiszlavicz L, Kaszaki J, et al. Zerumbone exerts a beneficial effect on inflammatory parameters of cholecystokinin octapeptide-induced experimental pancreatitis but fails to improve histology. Pancreas. 2007;35:249–255. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e318070d791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdelwahab SI, Abdul AB, Devi N, et al. Regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia by zerumbone in female Balb/c mice prenatally exposed to diethylstilboestrol: involvement of mitochondria-regulated apoptosis. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2010;62:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taha MM, Abdul AB, Abdullah R, Ibrahim TA, et al. Potential chemoprevention of diethylnitrosamine-initiated and 2-acetylaminofluorene-promoted hepatocarcinogenesis by zerumbone from the rhizomes of the subtropical ginger (Zingiber zerumbet) Chem Biol Interact. 2010;186:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami A, Takahashi D, Kinoshita T, et al. Zerumbone, a Southeast Asian ginger sesquiterpene, markedly suppresses free radical generation, pro-inflammatory protein production, and cancer cell proliferation accompanied by apoptosis: the alpha, beta-unsaturated carbonyl group is a prerequisite. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:795–802. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xian M, Ito K, Nakazato T, et al. Zerumbone, a bioactive sesquiterpene, induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in leukemia cells via a Fas- and mitochondria-mediated pathway. 2007;98:118–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakinah SA, Handayani ST, Hawariah LP. Zerumbone induced apoptosis in liver cancer cells via modulation of Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. Cancer Cell Int. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sung B, Jhurani S, Ahn KS, et al. Zerumbone down-regulates chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression leading to inhibition of CXCL12-induced invasion of breast and pancreatic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8938–8944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yodkeeree S, Sung B, Limtrakul P, Aggarwal BB. Zerumbone enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the induction of death receptors in human colon cancer cells: evidence for an essential role of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6581–6589. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdelwahab SI, Abdul AB, Zain ZN, Hadi AH. Zerumbone inhibits interleukin-6 and induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in ovarian and cervical cancer cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;12:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang S, Liu Q, Liu Y, et al. Zerumbone, a southeast Asian ginger sesquiterpene, induced apoptosis of pancreatic carcinoma cells through p53 signaling pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:936030. doi: 10.1155/2012/936030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murakami A, Takahashi M, Jiwajinda S, et al. Identification of zerumbone in Zingiber zerumbet Smith as a potent inhibitor of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced Epstein-Barr virus activation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999;63:1811–1812. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao D, Vogel V, Singh SV. Benzyl isothiocyanate-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells is initiated by reactive oxygen species and regulated by Bax and Bak. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2931–2945. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi S, Singh SV. Bax and Bak are required for apoptosis induction by sulforaphane, a cruciferous vegetable-derived cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2035–2043. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao D, Choi S, Johnson DE, et al. Diallyl trisulfide-induced apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells involves c-Jun N-terminal kinase and extracellular-signal regulated kinase-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2. Oncogene. 2004;23:5594–5606. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herman-Antosiewicz A, Singh SV. Checkpoint kinase 1 regulates diallyl trisulfide-induced mitotic arrest in human prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28519–28528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao D, Srivastava SK, Lew KL, et al. Allyl isothiocyanate, a constituent of cruciferous vegetables, inhibits proliferation of human prostate cancer cells by causing G2/M arrest and inducing apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:891–897. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cossarizza A, Baccarani-Contri M, Kalashnikova G, Franceschi C. A new method for the cytofluorimetric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potentials using the J-aggregate forming lipophilic cation 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;197:40–45. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu J, Zhang L. PUMA, a potent killer with or without p53. Oncogene. 2008;27:S71–S83. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mikhailov V, Mikhailova M, Degenhardt K, et al. Association of Bax and Bak homo-oligomers in mitochondria. Bax requirement for Bak reorganization and cytochrome c release. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5367–5376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:311–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panahi Y, Saadat A, Sahebkar A, et al. Effect of ginger on acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a pilot, randomized, open-label clinical trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:204–211. doi: 10.1177/1534735411433201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zick SM, Turgeon DK, Vareed SK, et al. Phase II study of the effects of ginger root extract on eicosanoids in colon mucosa in people at normal risk for colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1929–1937. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartwell LH, Kastan MB. Cell cycle control and cancer. Science. 1994;266:1821–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7997877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freed-Pastor WA, Prives C. Mutant p53: one name, many proteins. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1268–1286. doi: 10.1101/gad.190678.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antony ML, Kim SH, Singh SV. Critical role of p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis in benzyl isothiocyanate-induced apoptotic cell death. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi H, Chen J, Bhalla K, Wang HG. Regulation of Bax activation and apoptotic response to microtubule-damaging agents by p53 transcription-dependent and - independent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39431–39437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao D, Powolny AA, Moura MB, et al. Phenethyl isothiocyanate inhibits oxidative phosphorylation to trigger reactive oxygen species-mediated death of human prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26558–26569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hahm ER, Moura MB, Kelley EE, et al. Withaferin A-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells is mediated by reactive oxygen species. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]