Abstract

Human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) is a well-known biomarker that is overexpressed in many breast carcinomas. HER2 expression level is an important factor to optimize the therapeutic strategy and monitor the treatment. We used albumin-binding domain-fused HER2-specific Affibody molecules, labeled with AlexaFluor750 dye, to characterize HER2 expression in vivo. Near Infrared optical imaging studies were carried out using mice with subcutaneous HER2-positive tumors. Animals were divided into groups of 5: no treatment, 12 hours and one week after the treatment of the tumors with Hsp90 inhibitor 17-DMAG. The compartmental ligands-receptor model, describing binding kinetics, was used to evaluate HER2-expression from the time sequence of the fluorescence images after the intravenous probe injection. The normalized rate of accumulation (NRA) of the specific fluorescent biomarkers, estimated from this time sequence, linearly correlates with the conventional ex vivo ELISA readings for the same tumor. Such correspondence makes properly arranged fluorescence imaging an excellent candidate for estimating HER2-overexpression in tumors, complementing ELISA and other ex vivo assays. Application of this method to the fluorescence data from HER2-positive xenografts, reveals that the 17-DMAG treatment results in downregulation of HER2. Application of AngioSence750 probe confirmed anti-angiogenic effect of 17-DMAG, found with Affibody-Alexa750 conjugate.

Keywords: Breast cancer, 17-DMAG, HER2 receptors quantification, Fluorescence Imaging, Affibody

INTRODUCTION

Expression of HER2 receptors in several types of epithelial cancers is correlated with poor prognosis. New methods are being developed to target HER2-positive cells. It is clear that the success of HER2-targerted therapies depends on accurate characterization of HER2 expression 1. Therefore, the HER2 status should be consistently assessed in all patients with breast cancer to identify HER2-positive tumors that would qualify the patient for the treatment with currently used therapeutic agents such as trastuzumab. Up to now all available HER2 tests: FISH, ELISA, Immunohistochemistry have been based on ex vivo analysis of breast cancer specimens. Importantly these approaches do not allow real-time monitoring of changes in HER2 expression, essential for development of new HER2- targeting therapies.

Due to its minimal invasiveness, optical imaging presents an attractive option for serial imaging of tumors and monitoring of possible changes of receptor expression during the course of treatment. Reduced fluorescence background and enhanced tissue penetration by near infrared (NIR) light allows detection of targets located at the depth up to several centimeters in the tissues. Recently attention to novel fluorescence imaging techniques has been attracted by an interesting paper 2, where analysis of a time series of images, acquired after injection of an inert dye, allowed precise delineation and identification of major organs of a small animal, using differences in the dye’s in vivo biodistribution dynamics.

We have previously reported Affibody-based bioconjugates for in vivo optical imaging of HER2 3. Data analysis in the framework of compartmental ligands-receptor model revealed correlation between initial rate of accumulation of the fluorescent probe at the tumor and HER2 expression in the cancer cells 4. In this communication, we present a novel approach, based on these findings, to quantify HER2 expression in vivo by minimally invasive procedure. The normalized rate of accumulation (NRA) of the specific fluorescent biomarkers (Affibody), estimated from the time sequence of images, using a compartmental kinetic model, linearly correlates with the readings of a conventional ELISA ex vivo assay of the same tumor. Such relationship makes fluorescence imaging, using specific dyes, an excellent candidate to replace traditional ex vivo assessment of HER2 overexpression in tumors. In vivo character of our approach allows one to monitor the therapy and potentially map the distribution of HER2 receptors over the region of interest (ROI). We were able to reveal a strong correlation between downregulation of HER2 expression in human tumor xenografts treated with 17-DMAG 5, and temporal characteristics of fluorescence images. Corresponding ELISA tests quantitatively confirm these findings. This work may provide new non-invasive means for improved diagnosis and selection of patients for HER2-targeted therapies, and to monitor and estimate possible changes in receptor expression in response to therapeutic interventions.

Near Infrared (NIR) fluorescence optical imaging is already the modality of choice for preclinical studies, because of its minimal invasiveness, allowing multiple scans that are necessary for monitoring possible changes in receptor expression during the treatment. In the future, it may also become useful in the clinical setting. Although limited penetration depth and intrinsic autofluorescence originating from tissue preclude the use of visible light for most in vivo imaging applications, NIR fluorescence increases depth resolution dramatically. Combined with recent advanced mathematical modeling of propagation of light in tissue and technological improvements of sources and detectors, NIR optical imaging becomes feasible for clinical application. Several optical methods and systems available in the clinic today use light that can penetrate more than 5 centimeters deep inside the tissue. 6–13 With NIR fluorescence systems (NIRF) penetration depths, achieved up to now, are smaller, for example, the limit depth of 21 mm of NIRF intraoperative camera system was reported in [Pleijhuis RG, et al., “Near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging in breast-conserving surgery: Assessing intraoperative techniques in tissue-simulating breast phantoms”, EJSO Volume: 37(1) 32-, 2011].

In this study we focus on the changes in HER2 expression resulting from the treatment of HER2-positive BT474 tumor xenografts in mice with 17-DMAG. In the current study we have used HER2-specific Affibody molecules which are attractive candidates for NIR optical imaging, because of their high specificity and affinity to HER2, combined with quick clearance from the blood, as shown in previous in vivo imaging studies 14–16.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The HER2-specific Affibody® molecule with albumin binding domain, ABD-(ZHER2:342)2-Cys, which will be called “ABD-affibody” in this paper, was kindly provided by our Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) partner in Sweden (Affibody AB; http://www.affibody.com). All other reagents (750 C5-maleimide and 750 Antibody/Protein 1 mg-labeling kits, 17-DMAG (reconstituted with 0.9% sodium chloride for injection), AngioSense 750) were purchased from the commercial sources.

The ABD-(ZHER2:342)2-Cys Affibody molecules contain a unique C-terminal cysteine residue that allows site-specific labeling 17. This cysteine was used to fluorescently label the Affibody molecules with thiol-reactive AlexaFluor750-maleimide dyes, as described by Zielinski et al. 18.

Cell cultures and animal model

The human breast cancer cell line BT474 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA). BT474 has been chosen as a cell line with the highest HER2 expression level (+3). The cells were grown in a culture media at 37°C at 5% CO2 in a humidified environment using RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Pen/Strep (10,000U penicillin, 10 mg streptomycin). A solution of 0.05% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in PBS was used for cells’ detachment.

Female athymic nude mice (nu/nu genotype, BALB/c (NCR, NCI-Frederick, Frederick, MD), approximately five to eight weeks old, were used for these experiments, as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institutes of Health. In addition, all animal studies were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Animals. The effects of Hsp90 inhibition on the growth of a human breast cancer cell line (BT474) were investigated in a subcutaneous (s.c.) xenograft tumor model. Eight million BT474 cells suspended in 0.1 ml of 50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) were injected subcutaneously into the right shoulder. Mice were randomized and assigned to one of three groups: (i) control, before the treatment; (ii) 12 hours after completion of the treatment; and (iii) 7 days after completion of the treatment. Five and three mice per group were used for receptor quantification and angiogenesis study, respectively. Tumor diameters were measured periodically with calipers, and tumor volumes were calculated (4/3 × Π × length × width × depth/8). Intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 17-DMAG was initiated when mean tumor volume had reached approximately 400 mm3. To monitor the effects of Hsp90 inhibition, two groups of mice were treated with four doses of 17-DMAG (40 mg/kg) 24 h apart. After the experiment had been terminated, mice were euthanized and tumors were extracted for the assessment of the HER2 expression by ELISA.

In vivo near-infrared optical imaging

Fluorescence intensity was quantified using a previously described NIR fluorescence small-animal imager 19. Briefly, the system is based on a time-domain technique, where an advanced time-correlated single-photon counting device is used in conjunction with a high-speed repetition-rate tunable laser to detect individual photons. It contains a photomultiplier tube used as a detector, a temperature-controlled scanning stage with an electrocardiogram and temperature monitoring device for small animals, and a scanning head 10 mm wide and 6mm thick. The scanning head consists of multimode optical fibers that are used to deliver light from an excitation source and an emitted fluorescence signal to detector through the optical switch. The imager has a laser source for fluorescence excitation (λ = 750 nm), an emission filter (λ = 780 nm) for fluorescence detection, and a computer for data analysis. The imager scans in a raster pattern over the skin or other tissue surfaces at close distance of 1 to 2 mm to produce a real-time, two-dimensional image of the region of interest (ROI). A cooled, charge-coupled device (CCD) camera is used to guide the scan to the ROI, and to measure the fluorescence intensity distribution, which helps to locate the tumor inside the tissue. The measurements with the small animal imager were performed in such a manner that the source-detectors head is scanning only over a region of interest (ROI), i.e., tumor or corresponding contralateral area.

To analyze the target-specific accumulation of the imaging probes, mice were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane. Ten micrograms of ABD-affibody-AlexaFluor 750 conjugate was injected intravenously and imaged at several predetermined time points after injection. The mean and standard deviations of the fluorescence signal were calculated by averaging the maximum pixel values over the tumor area and corresponding contralateral site.

Estimates of HER2 receptor expression in vivo

We have previous shown that if dissociation rate constant koff is low enough to disregard ligand-receptor dissociation during the observation period, these variations can be approximated by the following function 20:

| (1) |

where in accordance with the kinetic model 20, parameter a is proportional to the total concentration of HER2 receptors in the tumor i.e., HER2 expression, while parameter b is proportional to the binding rate of fluorescent ligands with HER2 receptors and concentration of free ligands in the tumor tissue. Thus, initial rate of accumulation (in other words, binding) of HER2-specific fluorescent ligands at early times (t ≃ t1 =3h after the probe injection) is proportional to HER2 expression and concentration of free ligands in tissue, we normalize the time series data for different tumors to the same initial level, say unity, by dividing all intensity points for each case by a corresponding value of intensity (I (t1) ) before comparing observed accumulation rates of specific marker (describe in detail elsewhere 20). The derivative , presenting normalized initial rate of accumulation (NRA) obtained by fitting the normalized in vivo experimental fluorescence data to the model.

Current studies compared estimated NRA of several tumors (all 3+ BT474) with corresponding readings of ELISA assay, obtained ex vivo for the same tumor to quantify HER2 expression in vivo. For simplicity and to reduce potential problems, related to possible changes in HER2 overexpession during treatment with 17-DMAG, we limit our analysis to early-time imaging data 3h ≤ t ≤ 14h, when the saturation in the binding of our Affibody probe to HER2 is small, i.e. to the first approximation, fluorescence intensity from the tumor increases almost linearly at this time range.

Monitoring tumor vascularity

Tumor vascularity was imaged using AngioSense 750 (VisEn Medical, Inc., Bedford, MA). Anesthetized mice were injected intravenously with 2 nmol of AngioSense 750 in 150 μl of saline and imaged at predetermined time points. The fluorescence signal mean and standard deviation were calculated by averaging the maximum pixel values over the tumor area and corresponding contralateral side at different time points after the injection.

ELISA

Animals were sacrificed at the pre-determined time point after the series of optical imaging sessions. Tumor tissue was extracted and was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in −80°C. Tumor tissue was homogenized in a suspension buffer supplemented with proteases inhibitor mixture (Complete stop- Roche) and EDTA (5 mM), followed by HER2 extraction. Both receptor retrieval and HER2 ELISA were performed according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer, using serial dilutions of recombinant HER2 protein as standards. HER2 concentration is expressed in ng of HER2 per mg of total protein.

RESULTS

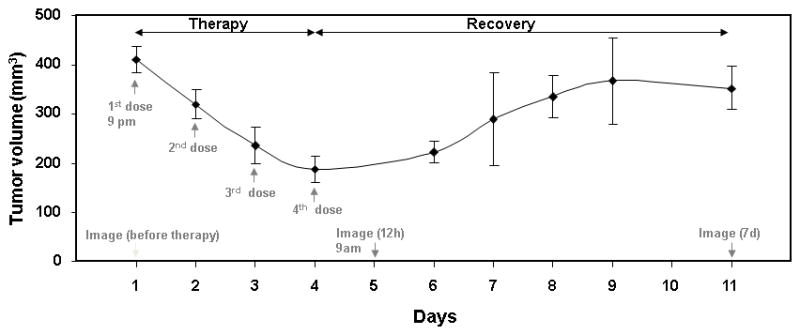

Application of 17-DMAG resulted in considerable reduction of the tumor size (~50%), as illustrated by figure 1. However, after the course of treatment (4 doses of 40 mg/kg 24 h apart) had been completed, the tumor quickly recovered, reaching almost its pre-treatment dimensions after one week. For half of the treated mice, a sequence of fluorescence images was obtained, starting 12 h after the course of treatment with 17-DMAG, when the effect of therapy is close to maximal. Another half of the treated mice was imaged, starting 7 days after the course of treatment, when the tumor had already recovered. The whole temporal sequence of the treatment/imaging experiments is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Tumor volumes before and at different time points after the course of treatment (n = 10 mice). Mice were treated with 4 doses of 17-DMAG 24 h apart. With the first dose of treatment, tumor volume started to reduce, but after the course of treatment, the tumor started to regrow to its original volume. To monitor the variations in the HER2 overexpression specific marker, Affibody-Alexa Fluor 750 conjugate was injected through the tail vein before, and 12 h and 7 d after the course of treatment.

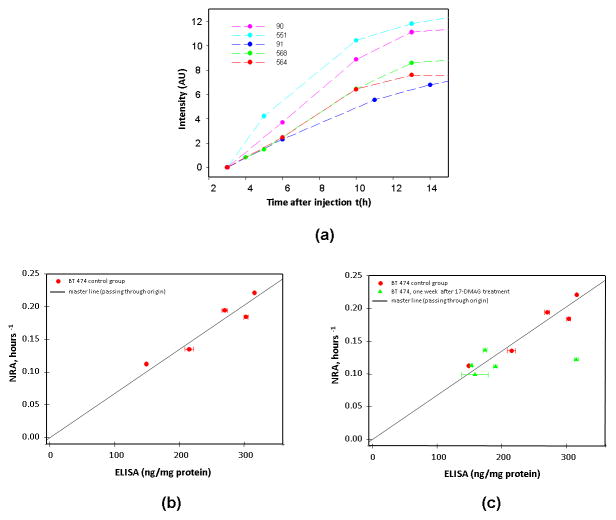

We have processed the data of all three groups of mice (untreated, 12h and 7d after the treatment) using our model described in 20 (see also Method section of this paper) and compared the found value of normalized rate of accumulation (NRA) with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) readings for corresponding xenografts. In figure 2a we present time courses of fluorescence intensities at the tumor, excluding the free ligand in blood contribution for 5 mice in the control group (i.e., untreated animals), obtained over a time range t~2.5h to14h after probe injection. The intensity values represent the normalized data for all mice to the same initial level of unity at time t1 = 3h after injection. Both NRA calculations and ELISA tests were performed completely independently. ELISA measurements have shown large variations in HER2 overexpression for the BT474 xenografts between individual mice in the control group (n = 5): 250±69 ng/mg of protein with observed maximum value of 315 ng/mg, being more than twice the minimum one (~148 ng/mg). Figure 2b, demonstrates the observed linear dependence between NRA and ELISA value of individual mouse tumors (n = 5), passing through the origin (zero intercept). Corresponding p-value for the test of the null hypotheses is equal to 1.25×10−5, showing that the found slope of this line is significantly different from zero from statistical point of view. Moreover, according to Akaike information criterion (AIC) the statistical model with zero intercept (AIC=47.9) is better than the linear regression with the intercept, as a fitting parameter (AIC=49.9) [M.J. Crawley “Statistics: An Introduction using R, Exercises, 4. Regression, http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/pls/portallive/docs/1/1171920.PDF]. We believe that this zero intercept linear relation can be considered as a master line, allowing one to predict ex vivo ELISA reading of HER2 overexpression for a specific tumor.

Figure 2.

a. Intensity values (tumor-contralateral) from control group (n = 5 mice/group)

b. Correlation between the Normalized Rate of Accumulation (NRA) of the fluorescent biomarker (Affibody-Alexa Fluor 750), from control group of mice with tumor BT474 and ELISA measurements obtained from the same tumor.

c. Correlation between the NRA and ELISA measurements from treatment group (n=5 mice/group) at 7days after the course of treatment, comparing to the control group. In both measurements HER2 overexpression and range of its variations are smaller as compare to control group.

As a test we used a third group of mice that has been imaged seven days after the course of treatment with 17-DMAG, when the tumor and related vascularization had progressed back to the pre-treatment level. For this group, our analysis shows much smaller variations in the NRA values from mouse to mouse (~12%), compared to the control group (see figure 2c). However, ELISA results seem to indicate that almost all data points occupy a narrow range: 168±16.7 ng/mg (i.e., with relative variation < 10%). The only observed exception presents a case of tumor with very high ELISA reading for HER2 overexpression (313 ng/mg, this is almost twice lower than recorded for the other mice in the group), making it an outlier according to the statistical outlier test (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). If we apply our master line, based on the control group, we would get an expected average reading of ELISA 172±20.4 ng/mg for the whole group or 170±23.1 ng/mg, if exclude mentioned above ELISA outlier. Both values are close to ELISA results, excluding outlier.

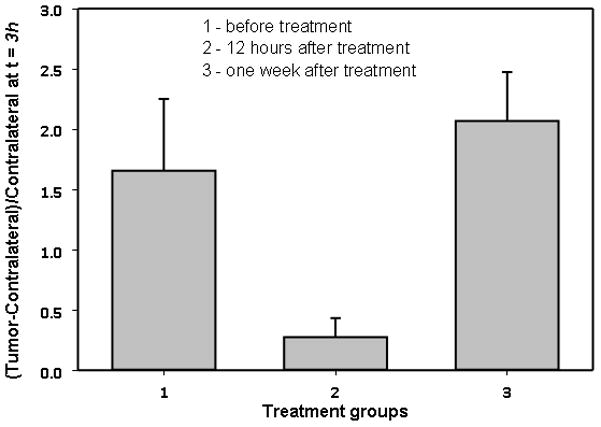

We like to mention that before analyzing the data for the 17-DMAG treated sub-samples of mice, we needed to verify our initial assumption that at early times t ~ t1 = 3h the fluorescent signal comes mostly from the free ligands in the blood. 17-DMAG therapy can potentially reduce the extra vasculature and corresponding additional blood volume, developed by the tumor angiogenesis. To analyze this effect, we have calculated the difference between the tumor and contralateral intensities at time t1 = 3h, normalized to the corresponding contralateral value. The same procedure was repeated for each experimental group: control, 12 h, and one week after the completion of treatment. Figure 3, presenting these ratios, demonstrate drastic variations between sub-samples: 12 h after treatment, the average ratio is reduced by 6.1 times, relative to the control group, while a week after therapy, it is much closer to that of the control group (actually ~25% higher). These variations should be related to observed changes in the tumor status after the therapy. At 12 h the effect of treatment is close to maximum, while after one week, the tumor seems to return to its pre-treatment state (see figure 1). It is not surprising that blood volume related to tumor vasculature is being restored to a level close to that of before treatment.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence intensity (Affibody-Alexa Fluor Conjugate) tumor-contralateral at early times (t=3h) assumed to originate from extra blood in the tumor area. Angiogenesis in the tumor area is suppressed at ~12 hours after the course of treatment.

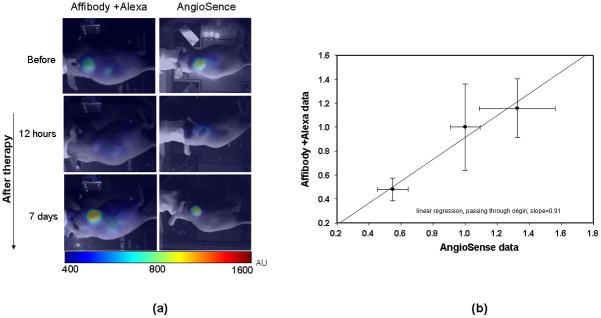

A natural explanation of such correlation is the blood origin of the early signal from the probe combined with an anti-angiogenic effect of the drug that suppresses extra vasculature immediately after treatment but, a week after the completion of the 17-DMAG therapy, the tumor’s size and corresponding angiogenesis return to their pre-treatment level. To substantiate this hypothesis, we performed independent in vivo measurements of the changes in tumor vasculature before and after treatment, using AngioSense 750 as shown in figure 4a. It was shown that this high molecular weight (250 kDa), fluorescent probe remains localized in the circulation for an extended time and reflects vascular network development in the organs. Moreover, vascular leakage contributes to an increased accumulation of the probe in tumor volume. We did find a strong correlation between the early signal from ABD-affibody-AlexaFluor 750 and the results obtained with AngioSense 750, as shown in figure 4b, where the normalized fluorescence intensities, observed at t1 = 3h with both contrast agents are presented for all three groups of mice (normalization is performed to an average intensity of the pre-treatment group). Thus, the application of the Affibody-Alexa Fluor 750 conjugate allows us not only to obtain information about the HER2 receptors overexpression, but also to assess anti-angiogenic properties of anti-cancer drugs in vivo, as shown in this study for 17-DMAG, which is known to affect angiogenesis 21. It is worth to note that, while the intensities, originating from the blood circulation, are relatively close for the control group and the group of mice, observed one week after the treatment (difference ~16%), blood volume in the tumor was reduced by ~2.1 times 12 hours after the treatment.

Figure 4.

a. Intensity distribution after injecting Angiosense through the tail vein before, and 12h and 7d after the course of treatment.

b. Correlation between Affibody- Alexa Fluor conjugate and AngioSence in tumor area after subtracting contralateral side at 3h after injecting through tail vein.

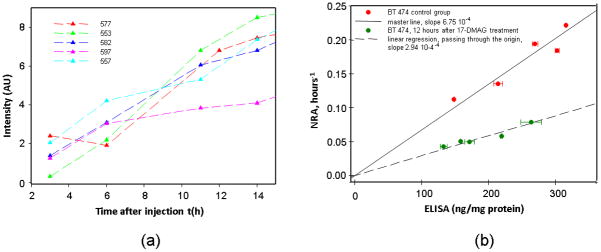

In accordance with the observed changes in tumor vascularization after treatment, there is no need to exclude an additional effect of free ligands in the tumor vasculature of animals imaged 12h after treatment with 17-DMAG. Therefore, for this group of mice (imaged 12 h post-treatment), we should modify accordingly the data processing that we have used so far. Observed differences between tumor and contralateral intensity measurements in the second group of mice (12 h after the course of the treatment) for 3h ≤ t ≤ 14h are presented in figure 5a. The NRA of fluorescence intensity growth at the tumor side have been calculated according to our modified kinetic model, i.e., under an assumption of no additional blood circulation in the tumor area, and have been compared with ex vivo ELISA readings on HER2 overexpression, measured for the same tumor. For the 17-DMAG-treated mice 12 h after treatment, corresponding ELISA readings are on average 33% lower than those for the control group: 189±52 ng/mg with a similar relative variance of ~28%. The results clearly indicate good linear correlation between NRA and ELISA readings (NRA relative variance ~25%) as shown in figure 4b. However, the slope of NRA-ELISA dependence (modified master line) is ~2.2 times smaller, likely reflecting observed ~2.1 times reduction in the mean blood volume at the tumor site, because NRA should be proportional to available concentration of free ligands at the tumor site.

Figure 5.

a. Intensity values (tumor-contralateral) from treatment group (12 h after the course of treatment) (n = 5 mice/group)

b. Correlation between the NRA and ELISA measurements obtained from treatment group (n = 5 mice/group) at 12 h after the course of treatment. (modified procedure; no additional blood circulation in the tumor area is assumed). For the 17-DMAG-treated mice 12 h after treatment, the slope of NRA-ELISA dependence (modified master line) is ~2.2 times smaller.

DISCUSSION

Application of molecular imaging to assess in vivo expression of HER2 is crucial for the success of HER2 targeted therapies 22. Several recent reports address the problem with the currently used ex vivo methods of HER2 assessment 1,4 and propose the alternative molecular imaging-based approaches such as PET 22–23. A novel approach to evaluate in vivo HER2 receptor expression levels in the tumor using Affibody-based fluorescent probes was suggested in our previous work 20. The temporal variations of the fluorescence signal, originating from the tumor xenograft, were analyzed within the framework of a three-compartment kinetic model, incorporating the signals from free ligands in blood plasma, free ligands in tissue, and HER2-bound ligands. From the measurements at the contralateral side, it was established that concentration of the free ligand in the bloodstream soon after tail vein injection of the contrast agent is well described by a single exponential decay with characteristic time of ~27 h. On the other hand, binding of the HER2-targeted fluorescence contrast agent to HER2 receptors in the tumor area has been clearly observed. Moreover, a sequence of 8–9 fluorescence images, starting 3 h after injection, (4–5 of them obtained at the early stages of fluorophore accumulation t ≤ 21h ) allowed us to estimate slope of the increasing fluorescence intensity in the tumor at an early time after injection (accumulation phase of the probe). This parameter showed a good linear correlation with quantitative HER2 amplification/overexpression data obtained for three types of HER2 positive breast carcinomas (BT474, MDA-MB361, MCF7) with different levels of HER2 overexpression (ranging from 1+ to3+) as measured by conventional ex vivo techniques FISH and ELISA. Moreover, the analysis limited only to the slope values obtained for BT474 xenografts also show very good linear correlation with ELISA readings, obtained independently ex vivo for the corresponding individual tumors.

In this study we have extended our analysis of HER2 expression to monitor in vivo the response of HER2-positive tumors (BT474) to a new anti-cancer agent, 17-DMAG, known to reduce the HER2 expression in treated tumors. As a standard control, we have used ex vivo assessment of HER2 protein concentration in the same tumors by ELISA. We have found a good linear correlation between ELISA readings and initial slopes of the increase of signal intensity in the tumor area, obtained from fitting our original kinetic model 20 to the observed time courses of fluorescence intensities, not only for the control group of mice, but also for the mice imaged 12 h after treatment, when additional vascularization in the tumor area becomes negligible due to the effect of the drug. The latter condition is substantiated by our direct measurements with AngioSense 750 dye. For the mice imaged one week after the treatment, both ELISA data and the initial slopes were in a very narrow range, when tumor progressed back to its pre-treatment status, after exclusion of one ELISA outlier from the analysis. Our results showed that analysis of temporal changes in tumor-associated fluorescence following i.v. injection of ABD-affibody-AlexaFluor probe allows quantification of HER2 expression in the individual tumors in vivo.

To avoid potential complications due to variations in HER2 expression, related to treatment itself, and to reduce time window of fluorescence measurements required for reliable fitting of the kinetic model to the data, we have limited our analysis to temporal changes of signal in a much narrower range 3h≤t≤14h after the injection of Affibody conjugate than our previous analysis mentioned in Chernomordik et al 20. Good linear correlations between these values for individual mice were found for the first two groups of mice; the third group is also consistent with linear regression for the control group after exclusion of the above-mentioned outlier in ELISA readings.

The observed correlations suggest that our method can be used as a basis to estimate HER2 overexpression in vivo. The shorter required range of data collection, considered here is advantageous: it is easier to collect necessary data during a shorter period of time, and the method is applicable when no extended-time data are practically available. It should be noted that for other fluorescent dyes, the accumulation of the dye in the tumor can proceed much faster than for the ABD-affibody-AlexaFluor conjugate. In such a case, it would be harder to get accurate time sequences of fluorescence signal measurements during only the dye accumulation phase and the data, obtained at the probe saturation stage, would be needed for an accurate quantification of HER2 overexpression.

Analysis of the therapeutic effect of the anti-cancer drugs would not be complete without addressing their potential effect on the angiogenesis in the tumor area. Using early-time data (~3h after injection of fluorescent contrast agent), when, according to our model, almost all fluorescence in the tumor area comes from the free ligands in the blood circulation, we have shown by in vivo measurements that 17-DMAG has a strong anti-angiogenesis effect in the treatment of BT474 carcinoma, as it has been demonstrated earlier by other methods in the literature for other cases 24–25. Our findings are substantiated by independent direct measurements of fluorescence, using vasculature-specific contrast agent AngioSense 750. These results indicated that temporal variations of fluorescence intensities after injection of HER2-specific markers can be used not only to quantify HER2 expression in tumors before and after treatment, but also to provide information regarding the anti-angiogenic properties of a compound and, thereby, further validating the choice of neo-adjuvant therapy.

We have shown that the compartmental ligands-receptor model can be used to estimate HER2 expression from data obtained by NIR optical imaging of ABD-affibody-based, HER2-specific probes. Normalized rate of accumulation (NRA), characterizing the temporal dependence of the fluorescence intensity detected in the tumor, linearly depends on the HER2 expression, as measured ex vivo by an ELISA assay for the same tumor. Thus, for a given instrumentation and target (mouse in these pre-clinical studies) we should first obtain the master line, similar to one described above. Being minimally invasive, suggested methodology can be used to assess/monitor HER2 overexpression before and after treatment, using corresponding master line. It allowed us to detect the downregulation of HER2 expression in human tumor xenografts treated with 17-DMAG. We have also observed that, up to 3 h post-injection, most of the probe is in the blood circulation, and the detected signal at this point is proportional to the blood volume as measured by AngioSense 750. Our results suggest that optical imaging using Affibody-ABD-based probes, combined with mathematical modeling, is a promising tool for noninvasive monitoring of the possible effect of therapeutic intervention on receptor expression and tumor vasculature. It should be noted that our focus on analysis of signal changes as a function of time, does not involve high-resolution mapping of the ROI and sophisticated 3-D reconstruction algorithms (that up to now have not been successfully realized for clinical studies). While limited in its scope to evaluation of overexpression of specific receptors in the tumor area (i.e. in the region with highest fluorescence intensity, originating from specific markers), it is much less sensitive to many uncertainties, characteristic for deep tissue imaging, and can be useful for “optical biopsy” of the tumor in vivo, for example, for patient selection or to monitor the response to therapy. Our approach is based on comparison of fluorescent images of the ROI, obtained at subsequent time points after injection of the contrast agent. Under the reasonable assumption that optical properties of the tissue/tumor and imaging geometry are not changed after injection (at least for ~30–70 h in the considered case of mouse imaging), the attenuation coefficient, related to photon migration in the turbid media, stays the same. Therefore, one can expect that after initial curve normalization at t = t1 (see above) variations in fluorescence intensities due to a specific marker are determined by kinetics of its binding to corresponding receptors and/or its washout from the blood circulation.

Further experiments are needed to investigate the limitations of the future clinical version of our system, in particular, the maximum distance between the imager head and the tumor to get quantitative fluorescence information under different experimental conditions. If sensitivity and spatial resolution of the imaging instrumentation are sufficient, suggested method likely to be applicable even to map HER2 overexpression at the main tumor and characterize some metastatic tumors (excluding distant metastases in the bones, lungs etc.). Potential targets of the proposed approach may include, for example, axillary lymph nodes, where cancer cells have spread, if these nodes are not deeper than the penetration depth limit of the NIR system.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure of authors: This research is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Allison M. Biomarker-led adaptive trial blazes a trail in breast cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:383–384. doi: 10.1038/nbt0510-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillman EM, Moore A. All-optical anatomical co-registration for molecular imaging of small animals using dynamic contrast. Nat Photonics. 2007;1:526–530. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2007.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allred DC. Biomarkers predicting recurrence and progression of ductal carcinoma in situ treated by lumpectomy alone. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:585–587. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips KA, Marshall DA, Haas JS, et al. Clinical practice patterns and cost effectiveness of human epidermal growth receptor 2 testing strategies in breast cancer patients. Cancer. 2009;115:5166–5174. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meric-Bernstam F, Hung MC. Advances in targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 signaling for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6326–6330. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dierkes T, Grosenick D, Moesta KT, et al. Reconstruction of optical properties of phantom and breast lesion in vivo from paraxial scanning data. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:2519–2542. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/11/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grosenick D, Moesta KT, Moller M, et al. Time-domain scanning optical mammography: I. Recording and assessment of mammograms of 154 patients. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:2429–2449. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/11/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grosenick D, Moesta KT, Wabnitz H, et al. Time-domain optical mammography: initial clinical results on detection and characterization of breast tumors. Appl Opt. 2003;42:3170–3186. doi: 10.1364/ao.42.003170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grosenick D, Wabnitz H, Moesta KT, et al. Concentration and oxygen saturation of haemoglobin of 50 breast tumours determined by time-domain optical mammography. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:1165–1181. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/7/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosenick D, Wabnitz H, Moesta KT, et al. Time-domain scanning optical mammography: II. Optical properties and tissue parameters of 87 carcinomas. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:2451–2468. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/11/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Intes X. Time-domain optical mammography SoftScan: initial results. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ntziachristos V, Yodh AG, Schnall M, et al. Concurrent MRI and diffuse optical tomography of breast after indocyanine green enhancement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2767–2772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040570597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinneberg H, Grosenick D, Moesta KT, et al. Scanning time-domain optical mammography: detection and characterization of breast tumors in vivo. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2005;4:483–496. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer-Marek G, Kiesewetter DO, Capala J. Changes in HER2 expression in breast cancer xenografts after therapy can be quantified using PET and (18)F-labeled affibody molecules. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1131–1139. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramer-Marek G, Kiesewetter DO, Martiniova L, et al. [18F]FBEM-Z(HER2:342)-Affibody molecule-a new molecular tracer for in vivo monitoring of HER2 expression by positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1008–1018. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0658-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lofblom J, Feldwisch J, Tolmachev V, et al. Affibody molecules: engineered proteins for therapeutic, diagnostic and biotechnological applications. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2670–2680. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundberg E, Hoiden-Guthenberg I, Larsson B, et al. Site-specifically conjugated anti-HER2 Affibody molecules as one-step reagents for target expression analyses on cells and xenograft samples. J Immunol Methods. 2007;319:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zielinski R, Lyakhov I, Jacobs A, et al. Affitoxin--a novel recombinant, HER2-specific, anticancer agent for targeted therapy of HER2-positive tumors. J Immunother. 2009;32:817–825. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181ad4d5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassan M, Riley J, Chernomordik V, et al. Fluorescence lifetime imaging system for in vivo studies. Mol Imaging. 2007;6:229–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chernomordik V, Hassan M, Lee SB, et al. Quantitative analysis of HER2 receptors expression in vivo by near-infrared optical imaging. Molecular Imaging. 2010;9:192–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaur G, Belotti D, Burger AM, et al. Antiangiogenic properties of 17-(dimethylaminoethylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin: an orally bioavailable heat shock protein 90 modulator. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4813–4821. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouchelouche K, Capala J. ‘Image and treat’: an individualized approach to urological tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22:274–280. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283373d5c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tolmachev V. Imaging of HER-2 overexpression in tumors for guiding therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2999–3019. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Candia P, Solit DB, Giri D, et al. Angiogenesis impairment in Id-deficient mice cooperates with an Hsp90 inhibitor to completely suppress HER2/neu-dependent breast tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12337–12342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2031337100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanderson S, Valenti M, Gowan S, et al. Benzoquinone ansamycin heat shock protein 90 inhibitors modulate multiple functions required for tumor angiogenesis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:522–532. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]