Abstract

Uremic encephalopathy is a well-known disease with typical MR findings including bilateral vasogenic or cytotoxic edema at the cerebral cortex or basal ganglia. Involvement of the basal ganglia has been very rarely reported, typically occurring in uremic-diabetic patients. We recently treated a patient who had non-diabetic uremic encephalopathy with an atypical lesion distribution involving the supratentorial white matter, without cortical or basal ganglia involvement. To the best of our knowledge, this is only the second reported case of non-diabetic uremic encephalopathy with atypical MR findings.

Keywords: Uremic encephalopathy, Magnetic resonance imaging, Diffusion-weighted imaging

INTRODUCTION

Uremic encephalopathy (UE) may result from multiple metabolic derangements associated with renal failure and is characterized by acute or subacute onset of reversible neurologic symptoms. Previous studies have reported that imaging findings of UE indicate either 1) cortical involvement or 2) basal ganglia (BG) involvement (1-5). UE, involving the cortical region in particular, can cause reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (PRES). BG involvement is quite rare. We recently encountered a case of non-diabetic UE with supratentorial white matter (WM) involvement, without any cortical or BG involvement indicated on MRI. To the best of our knowledge, only one case with atypical Magnetic resonance (MR) findings similar to our case has been reported previously (6). Hence, we report this case along with a literature review.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old man visited the emergency department of our hospital. He presented with subacute onset of right facial palsy and motor weakness of the ipsilateral extremities. On admission, the patient developed acute dysarthria. On the same day, he showed similar symptoms, which spontaneously disappeared within 5 minutes. The patient had no medical history of diabetes mellitus (DM) or hypertension but was born mentally retarded. According to his guardian, he developed dysuria after suffering a bladder injury as a child.

A neurologic examination revealed central-type facial palsy on the right side and mild motor weakness of the right upper and lower limbs (motor grade 4+). Laboratory examinations revealed elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (58.7 mg/dL), creatinine (6.0 mg/dL), and parathyroid hormone (190.3 pg/mL) levels, and a mild decrease in the serum calcium level (6.7 mg/dL). The results of cerebrospinal fluid analysis, blood sugar detection, and other laboratory tests were normal. Electroencephalography did not show epileptiform discharge or electrophysiologic evidence of a conduction defect in either visually evoked potential pathway.

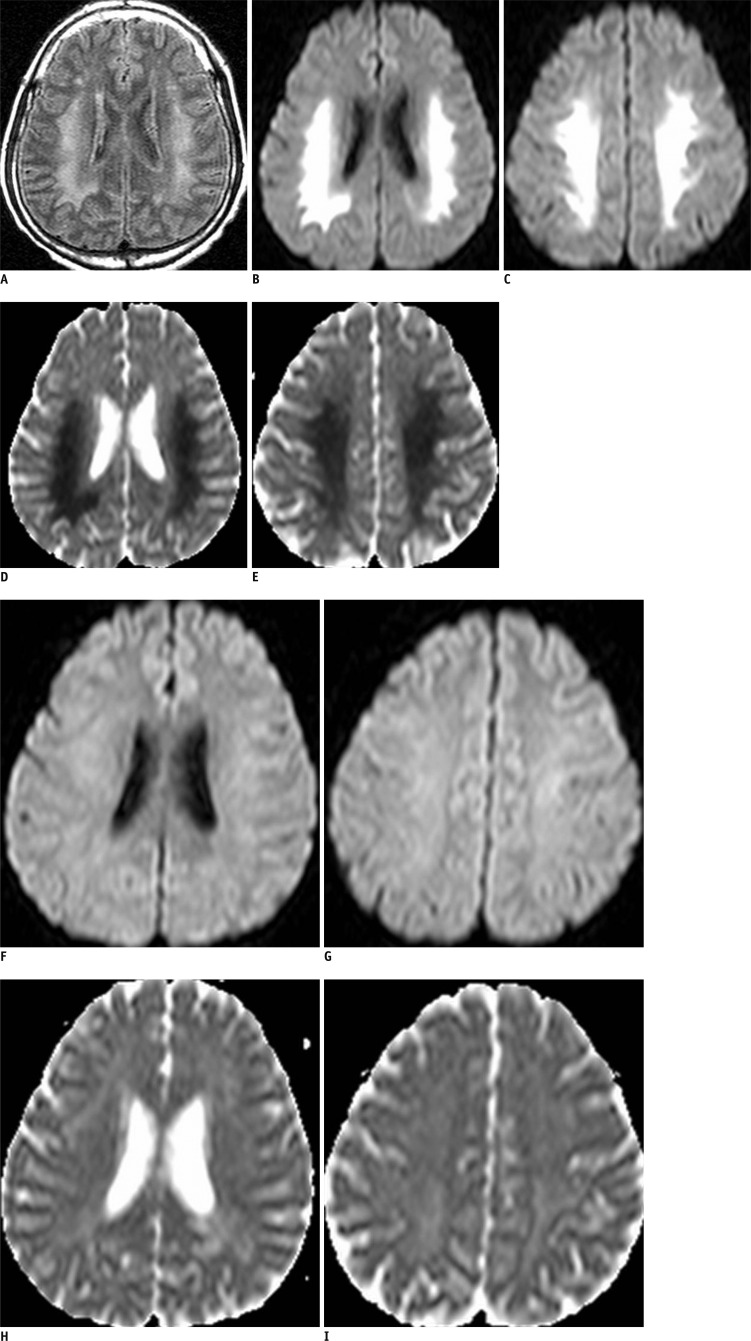

On admission, the patient underwent brain MRI and noncontrast-enhanced abdominal CT. The latter showed chronic obstructive uropathy with a distended bladder, severe hydronephrosis, and dual renal atrophy. The initial T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR images showed bilateral symmetric confluent areas of hyperintense signal alteration involving the supratentorial WM without cortical or BG involvement (Fig. 1A). They also showed diffusion restriction, indicative of cytotoxic edema (Fig. 1B-E).

Fig. 1.

Brain MRI in 36-year-old man with right facial palsy and motor weakness.

Brain MRI performed upon admission. Initial FLAIR reveals confluent high signal intensities of cerebral white mater, sparing cortex and basal ganglia (A). These lesions show high signal intensities on DWI and decreased ADC values (B-E). FLAIR = fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, DWI = diffusion-weighted imaging, ADC = apparent diffusion coefficient. Follow-up magnetic resonance (MR) scan obtained after 7 days, when symptoms had improved. MR images show that lesions, which showed abnormal signal intensities, are completely resolved (F-I).

The patient was hospitalized for treatment and a cystostomy was performed. After 5 days, the neurological symptoms were gradually and completely reversed and the BUN level (29.8 mg/dL) decreased.

Seven days after admission, the patient underwent follow-up MRI, which demonstrated complete resolution of the lesions (Fig. 1F-I).

DISCUSSION

Uremic encephalopathy is a well-known complication in renal failure patients and is characterized by a brain syndrome with various neurologic symptoms resulting from brain edema. These symptoms manifest acutely or subacutely and are usually reversible (1, 2, 5, 6).

According to reports thus far, UE can be classified into 2 types: 1) showing cortical involvement or 2) showing bilateral BG involvement. The former is more common and it is linked to PRES. Cortical involvement may develop in any uremic patient, and DM does not have a great effect on the involvement (1, 5, 6). The latter type is rarer and Asian patients with DM are usually affected by it (1-5). Further, in the cortical type, the radiological manifestation mainly includes vasogenic edema, but in the BG type, it can include vasogenic and cytotoxic edema (7).

The pathogenetic association between the types of UE is unclear. Factors such as uremia, methylguanidine, parathyroid hormone, aluminum, neurotransmitters, brain osmolality, metabolic acidosis, hypo- or hyper-glycemia, changes in cerebral blood flow, and metabolic acidosis have been cited as causes of UE (1, 8-10). Typically, it is a complex combination of these factors that contributes to the pathophysiology of UE rather than any one factor acting alone. Previous works on UE have explained some possible mechanisms: 1) hyperglycemia increases blood-brain barrier permeability in diabetic-uremic patients; 2) increased levels of uremic molecules and toxins may inflict toxic and metabolic injury on brain tissue that has been weakened by microangiopathic changes, energy utilization failures, or vascular autoregulation collapse (BG is particularly vulnerable to toxins); 3) the cerebral oxygen consumption is significantly reduced in uremia, and this may affect focal cellular metabolism and result in cellular edema (1-8).

In most reported cases, lesions on neuroimaiging and symptoms disappeared when uremia was treated. One patient, in particular, showed residual neurologic impairments characterized as cystic degeneration at the medial BG (globus pallidus) on a follow-up MR scan and very low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values on the initial MR scan (2). Some previous reports suggest that the long term prognosis of UE is not good because many patients die or require prolonged intensive care because of the complications related to UE but not UE itself. Also, prognoses of patients who have UE with BG involvement and very low ADC values, or diabetic UE, are poorer (1, 2).

The MRI results of our case were unlike those of most reported cases (1-5, 7, 8). Our case showed bilateral confluent reversible cytotoxic edema at the cerebral WM and did not involve the cortex or BG. Moreover, our patient had facial palsy and transient ipsilateral motor weakness instead of the typical changes in mental status or movement symptoms. In the past, only one other case had similar reports of subacute onset of facial palsy and nonfluent aphasia (6). Excluding that case and ours, all the cases documented to date involved diabetic uremic patients. Several conditions including delayed anoxic encaphlopathy, hypoglycemia, extrapontine myelinolysis, toxic encephalopathy, and metabolic acidosis present similar imaging findings. However, these conditions are associated with specific laboratory findings or clinical history. In our case, the patient did not have hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, and any history of anoxia or exposure to toxins. Therefore, we could exclude the effect of other conditions. On the basis of the symptoms presented here, we believe our findings are divergent from the two known types of UE.

Thus, we propose that UE can be classified into 3 types on the basis of radiological manifestations: 1) the cortical type, which is the most common, 2) the BG type, which is uncommon and usually develops in diabetic-uremic patients, and 3) the atypical or WM type, which is the rarest. UE may develop in non-diabetic uremic patients with different neurologic symptoms such as facial palsy. Moreover, non-diabetic UE can show unique and atypical imaging findings. Even these lesions are considered cytotoxic edema. However, if adequate treatment, including removal of uremic toxins and correction of metabolic acidosis, is provided, complete neurological and radiological recovery can be achieved.

References

- 1.Wang HC, Cheng SJ. The syndrome of acute bilateral basal ganglia lesions in diabetic uremic patients. J Neurol. 2003;250:948–955. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-1122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim TK, Seo SI, Kim JH, Lee NJ, Seol HY. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the syndrome of acute bilateral basal ganglia lesions in diabetic uremia. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1267–1270. doi: 10.1002/mds.20932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raskin NH. Neurological complications of renal failure. In: Aminoff MJ, editor. Neurology and general medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. pp. 303–319. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raskin NH, Fishman RA. Neurologic disorders in renal failure (first of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1976;294:143–148. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197601152940306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang HC, Brown P, Lees AJ. Acute movement disorders with bilateral basal ganglia lesions in uremia. Mov Disord. 1998;13:952–957. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prüss H, Siebert E, Masuhr F. Reversible cytotoxic brain edema and facial weakness in uremic encephalopathy. J Neurol. 2009;256:1372–1373. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon CH, Seok JI, Lee DK, An GS. Bilateral basal ganglia and unilateral cortical involvement in a diabetic uremic patient. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111:477–479. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okada J, Yoshikawa K, Matsuo H, Kanno K, Oouchi M. Reversible MRI and CT findings in uremic encephalopathy. Neuroradiology. 1991;33:524–526. doi: 10.1007/BF00588046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akmal M, Goldstein DA, Multani S, Massry SG. Role of uremia, brain calcium, and parathyroid hormone on changes in electroencephalogram in chronic renal failure. Am J Physiol. 1984;246(5 Pt 2):F575–F579. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1984.246.5.F575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biasioli S, D'Andrea G, Chiaramonte S, Fabris A, Feriani M, Ronco C, et al. The role of neurotransmitters in the genesis of uremic encephalopathy. Int J Artif Organs. 1984;7:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]