Abstract

A 67-year-old woman presented with memory impairment and behavioral changes. Brain MRI indicated hepatic encephalopathy. Abdominal CT scans revealed an intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt that consisted of two shunt tracts to the aneurysmal sac that communicated directly with the right hepatic vein. The large tract was successfully occluded by embolization using the newly available AMPLATZERTM Vascular Plug II and the small tract was occluded by using coils. The patient's symptoms disappeared after shunt closure and she remained free of recurrence at the 3-month follow-up evaluation.

Keywords: Hepatic encephalopathy, Portosystemic shunt, Surgical, Embolization, Therapeutic

INTRODUCTION

Intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt (IPSVS) is a rare vascular abnormality that involves persistent communication between the intrahepatic portal vein and the hepatic venous system via an anomalous intrahepatic venous tract. Since IPSVS typically presents with no apparent symptoms, it often goes undiagnosed until incidental detection on imaging for the evaluation of liver disease is performed. Treatment of IPSVS by shunt closure must be considered when patients with IPSVS present with symptoms, particularly hepatic encephalopathy. Several methods of shunt closure by surgical ligation or embolization using various agents have been reported (1-4).

Among the various embolic agents available, the AMPLATZER™ Vascular Plug II (AVP II; AGA Medical, Plymouth, MN, USA), a second-generation multi-segmented and multi-layered cylindrical device, was developed for optimal embolization. The reported merits of using an AVP instead of coils include more accurate placement, decreased procedure time, and lower migration risk (5-7). The developers claim that its use reduces the time to occlusion compared to that of the conventional AVP. No study has yet investigated the efficacy of using the AVP II in the treatment of adult IPSVS patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Here we present a case of successful embolization in a patient with IPSVS using the AVP II.

CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old woman previously diagnosed with hypothyroidism with no history of liver disease or trauma presented with memory impairment of approximately one-month duration and behavioral changes that had begun three days previously. The patient presented with mild confusion on examination. Laboratory tests revealed an abnormally high ammonia level (149 mmol/L). After treatment with a Duphalac enema, her ammonia level dropped to 34 mmol/L.

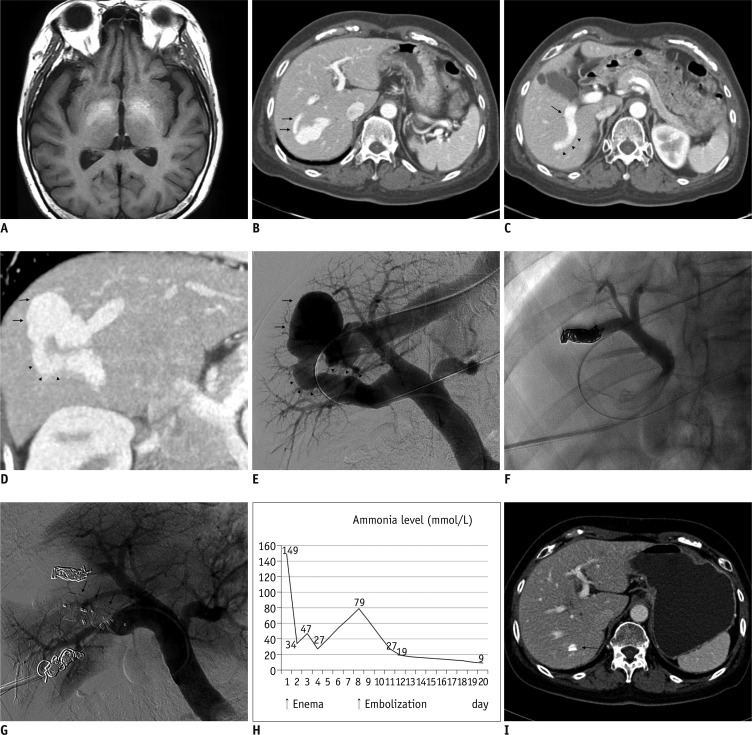

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed high signal intensity in the globus pallidus of the basal ganglia and the cerebral peduncle of the midbrain on T1-weighted imaging, suggestive of hepatic encephalopathy (Fig. 1A). Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen revealed two portovenous shunts involving an aneurysmal sac between the right portal and right hepatic veins with details as follows: a large shunt tract (8-9 mm in diameter, 5 cm in length) communicating from the central portion of the right posterior portal vein to the aneurysmal sac (3.6 × 2.5 cm) and a small shunt tract (4 mm in diameter, 3 cm in length) communicating directly from the right anterior inferior branch to the aneurysmal sac (Fig. 1B-D).

Fig. 1.

67-year-old woman with intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt (IPSVS).

A. T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing high signal intensity in globus pallidus of basal ganglia. B. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showing small shunt tract (arrows) communicating directly from right anterior portal branch to aneurysmal sac of IPSVS and hepatic vein. C. Axial CT scan showing large shunt tract (arrowheads) communicating from central portion of right posterior portal vein (arrow). D. Oblique reformatted CT scan showing aneurysmal sac (arrows) of IPSVS and large shunt tract (arrowheads) communicating from right posterior portal vein. E. Pre-embolization direct portogram showing aneurysmal sac of IPSVS (arrows) and large diameter of shunt tract (arrowheads). F. Spot image showing embolization of small shunt tract using coils via 5-Fr catheter. G. Post-embolization portogram showing no abnormal blood flow through shunt or AMPLATZER™ Vascular Plug II (AVP II) devices (arrows). H. Graph showing changes in serum ammonia level. Three days after procedure, serum ammonia level decreased to within normal range. I. Axial CT scan three months after procedure showing margin of AVP II (arrow) and obliteration of IPSVS and aneurysmal sac.

Based on these findings, the cause of the patient's encephalopathy was diagnosed as IPSVS, and shunt embolization was determined to be the appropriate treatment. An ultrasound-guided puncture of the right internal jugular vein was initially performed in preparation for a transjugular transvenous approach to embolization. However, the 5-Fr catheter (Cobra®; Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA) could not be safely advanced to the main portal vein due to kinking and distortion of the catheter in the aneurysmal sac. We were concerned about laceration of the aneurysmal sac due to increasing pressure on the sac wall; therefore, we changed to the transhepatic approach.

To access the portal system, ultrasound-guided transhepatic direct puncture of the right posterior branch of the portal vein was performed using a 21-gauge needle through the right intercostal space, while a 0.018-inch wire was inserted into the portal vein trunk. A pair of coaxially mounted catheters was advanced over the 0.018-inch wire; after exchange to a 0.035-inch guide wire, a 6-Fr sheath (Flexor Check-Flo Introducer®; Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA) was finally inserted into the portal vein along the guide wire. A 5-Fr catheter (Cobra®; Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA) was inserted into the main portal vein for performing direct portography and measuring portal vein pressure. The mean portal venous pressure was 13 mm Hg. A direct portogram confirmed the presence of IPSVS, revealing two shunt tracts from the portal vein (Fig. 1E). We measured the size and length of the two shunt tracts from a right oblique view using the measuring program of the angiographic equipment. Based on the CT and angiographic findings, we decided to use coils for the embolization of the small tract and AVP II for the embolization of the large tract.

We performed embolization of the small shunt tract by inserting a 5-Fr catheter into it through the anterior portal vein via the transhepatic route; embolization was then performed using three coils (Nester® embolization coil; Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA) (Fig. 1F). We performed embolization of the large shunt tract was performed by carefully advancing a 6-Fr long sheath into this shunt tract along a guide wire and then deploying the AVP II (12 mm in diameter) from the aneurysmal sac side of the tract. We first placed three consecutive AVP II devices to reduce procedure time and increase placement precision and then waited for 12 minutes. However, portography showed persistent flow into the aneurysmal sac, and additional AVP II devices were placed into the remnant tract. Complete occlusion of the large shunt tract was ultimately achieved with the use of five AVP-II devices.

Post-embolization portography via a 5-Fr catheter revealed the absence of blood flow through the shunt, confirming complete occlusion. Measurement of portal venous pressure after embolization revealed markedly increased pressure in the main portal vein from 13 mm Hg to 27 mm Hg. After occlusion was confirmed, eight coils were carefully inserted into the sheath's parenchymal tract to prevent massive bleeding (Fig. 1G).

Three days after the procedure, laboratory tests indicated that the patient's serum ammonia level had decreased to within the normal range (Fig. 1H), while physical examination revealed complete remission of all symptoms related to hepatic encephalopathy. The patient was discharged four days after the procedure with no complications. Follow-up CT scanning three months after the procedure indicated occlusion of the IPSVS and collapse of the aneurysmal sac (Fig. 1I). Upon patient examination and consultation, we found no symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy or portal hypertension.

DISCUSSION

Intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt is a rare vascular malformation involving persistent communication between the portal vein and the hepatic vein that poses the risk of hepatic encephalopathy. Although neuroimaging has limited value in the diagnosis of IPSVS, it is useful in the differential diagnosis of diseases that share clinical features with IPSVS, such as stroke, encephalitis, and metabolic encephalopathies. MRI of the brains of patients with hepatic encephalopathy typically reveals bilateral high T1 signal intensity in the globus pallidus and the anterior midbrain. The occurrence of hepatic encephalopathy has been found to increase with age, likely due to decreasing brain tolerance of toxic metabolites with aging (1, 2, 8, 9). Several authors have argued that the seriousness of an IPSVS case depends upon patient age and shunt ratio; thus, they recommend the use of Doppler ultrasonography and abdominal CT scanning to determine IPSVS size, shape, and type, all of which are important considerations in determining a treatment plan (1, 3).

The routes used for shunt closure by embolization include the transileocolic, percutaneous transhepatic, and retrograde transcaval approaches (4). In the present case, we initially decided on a transcaval approach via the right internal jugular vein; however, after finding that the catheter and sheath could not be safely advanced into the main portal vein via the large shunt tract, so we used a percutaneous transhepatic approach. The most serious potential complication of this approach is massive intraperitoneal bleeding, which Lee et al. (10) reported after performing successful tract embolization. However, these authors used Gelfoam slurry (Spong ostan®; Johnson and Johnson, Ferrosan, Soeborh, Denmark), which cannot prevent peritoneal bleeding associated with high portal vein pressure. Intraperitoneal bleeding can be prevented by closing the sheath's parenchymal tract with a permanent embolic agent such as coils (4), as evidenced in this case.

The selection of an embolic agent from among the many types available, including coils, Gelfoam® particles, and polyvinyl alcohol, should be based on shunt size and morphology. We chose to use coils to treat the small shunt tract in this case based on reports of successful use of coils to treat small-diameter shunt tracts (2, 4). However, using embolic materials, including coils, in large shunt tracts poses the risk of material migration and subsequent distal embolization at an unwanted site, such as a pulmonary artery. To avoid this risk and considering reports that use of AVP, a self-expanding cylindrical device made of nitinol wire mesh, is more likely to result in successful embolization of large-diameter vessels, we chose to use the AVP II to perform embolization of the large shunt (5, 6, 10).

Although the AVP II developers claim that it significantly reduces time to occlusion compared to the earlier AVP models, the use of five AVP II devices was required to completely pack the large shunt in this case. As indicated by this result, the need to use multiple devices could be the primary weakness of the AVP II as an embolic material. Zhu et al. (6) reported that AVP devices required additional embolic material for splenic arterial embolization in 78% of patients five minutes after the initial AVP placement. Ringe et al. (7) reported that 1-3 AVP plugs were needed for portal vein embolization. Combined use of AVP II devices and embolization coils can reduce the number of required AVP II devices, but this approach requires longer procedure time and is technically difficult, particularly in large-diameter, short-length vessels.

In this case, the patient's portal pressure rose significantly after embolization due to sudden shunt blockage. Such a rise in portal pressure has the potential to produce portal hypertension-related symptoms such as ascites and variceal bleeding. Therefore, patient follow-up after embolization is required for the detection of portal hypertension (2).

Successful embolization of the patient with IPSVS described here indicates that the AVP II effectively occludes large-diameter shunts that manifest symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy.

References

- 1.Tsitouridis I, Sotiriadis C, Michaelides M, Dimarelos V, Tsitouridis K, Stratilati S. Intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunts: radiological evaluation. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2009;15:182–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiraoka A, Kurose K, Hamada M, Azemoto N, Tokumoto Y, Hirooka M, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy due to intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt successfully treated by interventional radiology. Intern Med. 2005;44:212–216. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oguz B, Akata D, Balkanci F, Akhan O. Intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt: diagnosis by colour/power Doppler imaging and three-dimensional ultrasound. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:487–490. doi: 10.1259/bjr/65168282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanoue S, Kiyosue H, Komatsu E, Hori Y, Maeda T, Mori H. Symptomatic intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt: embolization with an alternative approach. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:71–78. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.1.1810071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boixadera H, Tomasello A, Quiroga S, Cordoba J, Perez M, Segarra A. Successful embolization of a spontaneous mesocaval shunt using the Amplatzer Vascular Plug II. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:1044–1048. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9739-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu X, Tam MD, Pierce G, McLennan G, Sands MJ, Lieber MS, et al. Utility of the Amplatzer Vascular Plug in splenic artery embolization: a comparison study with conventional coil technique. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34:522–531. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9957-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ringe KI, Weidemann J, Rosenthal H, Keberle M, Chavan A, Baus S, et al. Transhepatic preoperative portal vein embolization using the Amplatzer Vascular Plug: report of four cases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:1245–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rovira A, Alonso J, Córdoba J. MR imaging findings in hepatic encephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1612–1621. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hegde AN, Mohan S, Lath N, Lim CC. Differential diagnosis for bilateral abnormalities of the basal ganglia and thalamus. Radiographics. 2011;31:5–30. doi: 10.1148/rg.311105041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SA, Lee YS, Lee KS, Jeon GS. Congenital intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt and liver mass in a child patient: successful endovascular treatment with an amplatzer vascular plug (AVP) Korean J Radiol. 2010;11:583–586. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2010.11.5.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]