This study provides new information on fruit ripening of Bursera, from a structural and phenological point of view, we show some development patterns that must be taken into account in future physiological, ecological and management studies.

Abstract

Background and aims

The deterioration of seasonally tropical dry forests will stop with the implementation of management plans for this ecosystem. To develop these plans, we require information regarding aspects such as germination and the presence of ‘empty seeds’ of representative species—like, for example, Bursera, a genus with a high number of endemic species of the Mesoamerican Hotspot—that would enable us to propagate its species. The main purpose of this study is to describe the phenological and structural characteristics of fruits of 12 Bursera species and provide useful data for future studies on germination and seed dispersal, and to acquire new and useful information to understand the phylogenetic relationships of the Burseraceae family.

Methodology

We described the phenology of fruit ripening in 12 species of Bursera. Fruits were collected from the study sites in three different stages of development. The histochemical and anatomical characteristics of fruits of all species were described with the use of inclusion techniques and scanning microscopy.

Principal results

There is a time gap between the development of the ovary and the development of the ovule in the 12 studied species. The exposed pseudoaril during the dispersion stage is an indicator of the seed's maturity and the fruit's viability. The Bursera fruit shows the same structural pattern as that of Commiphora, as well as many similarities with species of the Anacardiaceae family. All species develop parthenocarpic fruits that retain the structural characteristics of the immature fruits: soft tissues rich in nitrogen compounds and few chemical and physical defences. Insects were found mainly inside the parthenocarpic fruits in eight species of Bursera.

Conclusions

The dispersion unit in Bursera consists of a seed, a lignified endocarp that protects the seed, and a pseudoaril that helps attract seed dispersers. The production of parthenocarpic fruits is energy saving; however, it is necessary to evaluate the potential benefits of this phenomenon.

Introduction

Owing to the rapid deterioration of seasonally dry tropical forests (Sánchez-Azofeifa and Portillo-Quintero 2011), we need to select native plant species that will help regenerate this habitat and stop its fragmentation. To do this, it is necessary to know the biology, the ecology, and the propagation and management systems of the new species (Vázquez-Yanes et al. 1999). The genus Bursera is a dominant element of the seasonally tropical dry forest, especially in the Mesoamerican Hotspot (Myers et al. 2000) and specifically in Mexico. There are 106 species of Bursera, 80 of which are endemic to Mexico (Becerra 2005; Rzedowski et al. 2005; Becerra and Venable 2008). In spite of the richness, abundance and endemism of Bursera, the different processes that contribute to the reproductive success of the species, such as dispersion, pollination, competition, herbivory and the sexual system, and the dependence or contribution of each of these factors to their population dynamics, are practically unknown (Traveset 2002). The first step to understanding such a network of processes, and which constitutes the main purpose of this study, is to acquire knowledge of the Bursera fruit as the structure containing the dispersion unit. It will then be possible to develop further studies about germination, seed dispersal and, subsequently, recruitment and seedling survival.

According to descriptions by Rzedowski et al. (2004, 2005), Bursera seeds disperse through the ‘endozoochory syndrome’, which means that the seeds are protected against physical and chemical damage by a hard layer, their pulp is rich in nutrients and their colour contrasts with the colour of the surrounding vegetation (Van der Pijl 1982; Howe and Westley 1988). An obstacle for the propagation and management of Bursera has been the absence of information regarding its germination. The germination rate of the 12 studied species of Bursera was <50 %, mainly due to the presence of ‘empty’ seeds. These results were attributed to the immaturity of the embryo and to genetic factors such as endogamy (Andrés-Hernández and Espinosa-Organista 2002; Bonfil-Sanders et al. 2008). Two other species also showed the presence of ‘empty’ fruits (Verdú and García-Fayos 1998; Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008). These ‘empty’ fruits or seeds have been interpreted as parthenocarpy (the production of seedless fruits) but, excluding Bursera morelensis, the structural characteristics and the ecological role of seeded and seedless fruits remain unknown. Seed development in B. morelensis shows a time gap as regards the development of the ovary. The fertile ovule becomes latent for 7–11 months; the valves in these fruits are completely released, showing a brightly coloured pseudoaril (Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008). This same time gap was reported for Bursera delpechiana and B. medranoana (Srivastava 1968; Cortes 1998). Parthenocarpic fruits in B. morelensis are characterized by their development even in the absence of pollination, and abortion of the ovule is frequently caused by an abnormal growth of the ovary walls which ultimately crush the ovule. Regardless of the abortion of the ovule, the fruit continues its development, although as the stage of seed dispersal approaches, the fruit dries, the valves open partially, rarely falling off completely, and the fruit can remain on the tree even if the next flowering and fructification stages have started. During their development histologically, these fruits have fewer chemical and physical defences than those with seeds (Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008). The same research with B. morelensis suggests that abortion of the ovule can also be caused by insects; these seeds can be recognized by the holes left by the insects when they deposit their eggs or when they abandon the fruit. Bonfil-Sanders et al. (2008) also mention the presence of ‘empty’ seeds, deformed and with holes, although they do not refer to their possible origin. Considering that seeds develop from ovules and that, when mature, they have embryos, endosperm (in most cases) and testa (Esau 1985), the use of the term ‘empty seed’ in the literature is contradictory. The anatomical description of the Bursera fruit, absent in the literature, can contribute to understanding the arrangement of different layers of the pericarp, and to define the composition of the dispersal unit. It can also help to better understand the phylogenetic relationships with other members of the Burseraceae family which, for a long time, have been based on the morphological characteristics of the fruit (Becerra 2003; Daly et al. 2011), and with members of the Anacardiaceae family, to which it is strongly related (Wannan and Quinn 1990; Bachelier and Endress 2009).

Accordingly, the particular objectives of this study were (i) to describe the phenological characteristics of 12 species of Bursera with regard to the production and maturation of the fruit; (ii) to determine whether the fruit of Bursera with seeds has the same structural pattern, by using 12 species that represent the six groups comprising the genus according to Becerra (2003); (iii) to establish whether the ‘empty’ fruits' are parthenocarpic, and to assess their physical and chemical defenses from a histochemical and anatomical perspective; (iv) to determine whether the time lag between the development of the ovule and the development of the ovary is a common phenomenon in the 12 species; and (v) to determine whether the fruits of the 12 species are inhabited by insects, linking their presence to the phenological and structural characteristics of the fruits.

Materials and methods

Twelve species of Bursera trees and shrubs were studied (Table 1). Nine of these species are endemic to México (Rzedowski et al. 2004, 2005). Table 2 shows the characteristics of the collection sites. The fruits of the studied species can be found alone, in pairs, or in small groups. The ovary is bilocular or trilocular (depending on the species), with two ovules per locule. In general, only one seed develops and it will be totally or partially covered by a pseudoaril. Flowering takes place at the beginning of the rainy season between April and June (Rzedowski et al. 2004, 2005; Ramos-Ordoñez and Arizmendi 2011). Fruit production is annual, and the size of the harvest suggests a masting behaviour (Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2010).

Table 1.

Morphological characteristics of the fruit in 12 Bursera species and sampling site; nine of them are endemic to Mexico (a). Fruit form; number of valves of the fruit; number of locules in the ovary. Gathered information from Rzedowski et al. (2004, 2005) and Guízar-Nolazco and Sánchez-Vélez (1991).

| Species | Fruit form | Valves | Locules | Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. apteraa | Spherical to ovoid, apiculate | Three | Three | Puebla |

| B. aridaa | Ovoid, apiculate | Three | Three | Puebla |

| B. bicolora | Elongate | Two | Two | Morelos |

| B. bifloraa | Ellipsoid, ovoid | Two | Two | Puebla |

| B. bipinnata | Obovoid | Two | Two | Morelos |

| B. copalliferaa | Oblong capsule | Two | Two | Morelos |

| B. fagaroides | Ovoid to subspherical, slightly apiculate | Three | Three | Puebla |

| B. glabrifoliaa | Ellipsoid to spherical | Two | Two | Morelos |

| B. grandifoliaa | Ellipsoid, ovoid | Three | Three | Morelos |

| B. lancifoliaa | Ovoid | Three | Three | Morelos |

| B. schlechtendalii | Obliquely ovoid, apiculate | Three | Three | Puebla |

| B. submoniliformisa | Ovoid to obovoid | Two | Two | Puebla |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study sites. Information obtained from Férnández (1999), Medina (2000), Gómez-Garzón (2002) and Ceccon and Hernández (2009).

| Site 1 | Site 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Barranca de Muchil alluvial fan, San Rafael Coxcatlán, Tehuacan Valley, Puebla, México | Tembembe river basin, archeological zone of Xochicalco, San Agustín Tetlama, Morelos, México |

| Geographic coordinates | 18°12′ and 18°14′N | 18°48′ and 18° 50′N |

| 97°07′ and 97°09′W | 98° 17′ and 99° 19′W | |

| Altitude (m a.s.l.) | 1000 | 1200–1500 |

| Climate | Dry with summer rains | Warm |

| Mean annual temperature | 25 °C | 21 °C |

| Mean annual rainfall | 394.6 mm | 1000–1500 mm |

| Dry season | November to May | October to May |

| Predominant vegetation | Tropical deciduous forest | Tropical deciduous forest |

| Most important species | Fouqueria formosa, Bursera morelensis, Escontria chiotilla and Pachycereus weberi | Bursera copallifera, Bursera glabrifolia, Pseudosmodingium perniciosum, Ipomoea wolcottiana, Alvaradoa amorphoides and Dodonea viscosa |

Phenology

The phenology of the species was described after six visits to the study sites (2010: February, May, mid-June, end of July and early December; 2011: May 2011). The production periods of leaves, flowers and fruits of female individuals per species (n = 324, minimum 10 trees, maximum 40 trees) were registered after qualitative observations. Species from the state of Puebla had been checked previously (May 2005 to May 2007) (Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008). The flowering period of the species from the state of Morelos was determined after a literature search. The qualitative record of the reproductive period in which the trees were found was obtained during the first two visits. The approximate dates of the rainy season, the approximate amount of fruits produced by the trees and phenological periods were obtained through consultation with the inhabitants of the local community. The species were identified with the help of the literature (Guízar-Nolazco and Sánchez-Vélez 1991; Rzedowski et al. 2004) and local guides. The individuals in places that were difficult to access, or those that were too high up, were viewed through binoculars. The species with fruits—B. aptera, B. arida, B. fagaroides and B. schlechtendalii—were identified and marked from the beginning (February) by the characteristics of the trunk and the presence of fruits. The rest of the species were identified and marked once the flowers and leaves had developed (June).

Fruit features

Three fruit collecting stages were established during the fruiting season 2010–2011: the initial stage of development or when fruit set occurs, a middle stage that considered the latency period of the ovule and the final stage when seed dispersal occurs. The middle stage was defined as the period after the fruit set stage and before dispersal. The four species with fruits in February and May had a middle stage in December. According to the literature and people from the local community, fruit removal in other species began in October and ended in December, so the middle stage was established at late July.

Collections were made in three trees of each species chosen at random in order to determine the structural characteristics of fruits with seeds and of ‘empty’ fruits, as well as the developmental stage of the ovule with regard to the stage of maturation in which the fruit was found. The same trees were used in every collection; we collected 50 fruits per tree, they were fixed with FAA (formol, acetic acid, 96 % ethanol and water 1 : 0.5 : 5 : 3.5) and taken to the laboratory. All fruits were dissected under a stereoscopic microscope and grouped in three different categories after registering the proportion of fruits with ovules or developing embryos, and fruits with an aborted ovule, occupied or not by insects. The occupied fruits were those with insects in any stage of development, or those that had oviposition marks or exit holes. Three samples per category were chosen randomly, embedded in paraffin and slices between 6 and 8 µm cut with a microtome. Approximately 700 glass slides were stained with safranin–fast green in order to describe their characteristics. Five hundred and forty glass slides and different staining methods were used to reveal the presence of starch (Lugol test), tannins (Vanillin test), cutin and suberin (oil red O), lignin (phloroglucinol-HCl) and insoluble polysaccharides and proteins (naphthol black blue-periodic acid-Schiff reagent). A second group of samples was chosen and dried to a critical point, coated with gold and observed under a scanning electron microscope (SEM). All techniques were carried out according to López et al. (2005).

The stained glass slides were observed under a light microscope and a photographic record was created for all the results. Photographs were taken under an optical microscope (Olympus Provis AX70, Tokyo, Japan), a scanning microscope (JEOL Model JSM-5310LV, Tokyo, Japan; magnification 15× to 200 000×), and a stereoscopic microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Additionally, during the seed dispersal period, we collected from the trees (n = 30 fruits per species) fruits with an exposed pseudoaril as well as dry fruits, in order to describe their external characteristics.

Results

Phenology

The species had similar phenological characteristics except for their maturation periods. Two groups were created according to their shared characteristics. The first group (Group A) included B. bicolor, B. biflora, B. bipinnata, B. copallifera, B. glabrifolia, B. grandifolia, B. lancifolia and B. submoniliformis. The second group (Group B) included B. aptera, B. arida, B. fagaroides and B. schlechtendalii. Fruit maturation took place from June to December in Group A, and from June to May in Group B (Table 3). Leaf and flower production in all species took place during the third week of June, 1 week after the beginning of the rainy season. Floral buds, anthetic flowers and young green fruits (yellow fruits in B. aptera) of different sizes were seen in the same individual during this stage. Young fruits reach their final size in July. Fruits in the process of abortion (with brown shades) were seen in both groups. Dry fruits were seen in every visit in Group B, some from February to May which belonged to the 2009–2010 fruiting season. Leaves from the Group A trees began to fall. No abortion was seen in Group B. In species in Morelos, the canopy was slightly destroyed by herbivory. In Puebla, herbivory was seen only in B. submoniliformis. In December, species from Group A had seeds with an exposed pseudoaril, immature fruits and dry fruits; some species of birds were also seen searching for food on the branches and feeding on fruits with an exposed pseudoaril. Ants were seen carrying fruits with an exposed pseudoaril. Trees in Group B had no leaves left, only immature fruits and dry fruits. The dispersal stage was registered in May 2011.

Table 3.

Phenological characteristics of 12 species of Bursera. Group A includes B. bicolor, B. biflora, B. bipinnata, B. copallifera, B. glabrifolia, B. grandifolia, B. lancifolia and B. submoniliformis. Group B includes B. aptera, B. arida, B. fagaroides and B. schlechtendalii. Species checked at the end of the 2009–2010 fruiting season and during the season 2010–2011. The leaf, flower and fruit production periods, and the number of individuals per species (n = 324, minimum 10, maximum 40 trees) were qualitatively recorded. Species were identified with the help of the literature (Guízar-Nolazco and Sánchez-Vélez 1991; Rzedowski et al. 2004) and local guides.

| February–May | Mid-June | End of July | Beginning of December | May | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Initial | Intermediate | Final | ||

| Group A | Trees without leaves or reproductive structures | Production of leaves and flowers. Fruit set and fruit growth | Latent stage, immature fruits with their final size. Begins the leaf abscission. Dry fruits | Fruit maturation, exposed. Seed dispersal. Dry fruits | Trees without leaves or reproductive structures |

| Stage | Initial | Intermediate | Final | ||

| Group B | Fruit maturation, exposed pseudoaril Seed dispersal. Dry fruits | Leaf and fruit production. Fruit set and fruit growth. Dry fruits | Fruit growth. Latency stage, immature fruits with their final size. Trees with leaves. Dry fruits | Latency stage, immature fruits with their final size. Dry fruits. Leafless trees | Fruit maturation, exposed pseudoaril Seed dispersal. Dry fruits |

Fruit development

The fruit reaches its final size in the first stage of development (fruit set or fruit development) during a period no longer than 2 weeks. In species with a trilocular ovary, one of the ovules develops (rarely two), the locule carrying it expands, while the other two ovules shrink and the remaining ovules are aborted (Fig. 1). Once the fruit has reached its final size, the ovule stops developing and remains without visible changes from 5 to 6 months, in some cases 11 months; therefore, maturation is asynchronous. Subsequently, the ovule restarts its development until it becomes a seed: maturation is a 7-month process. The difference in species with a bilocular ovary is the latency period which lasts 3–4 months; seeds and fruits take <6 months to complete their development. During the seed-dispersal stage, the valves open and fall off, exposing the orange–red or red pseudoaril. In B. bicolor, we found fruits with one developing embryo in each locule; however, we do not know whether these seeds are viable because they are smaller than those that develop as a single seed. Moreover, no open fruits with two seeds were found. In species from Group B, as well as in B. lancifolia, B. grandifolia and B. copallifera, the seed was always completely covered by the pseudoaril. In B. biflora, the pseudoaril covered less than two-thirds of the seed. In the rest of the species (B. bicolor, B. bipinnata, B. submoniliformis and B. glabrifolia), coverage of the pseudoaril was either complete or incomplete. All dissected fruits with an exposed pseudoaril had an embryo, which suggests that fruits need to open the valves in order to ensure the presence of a seed.

Fig. 1.

Cross-sections of the bilocular ovary of B. submoniliformis (A), and a trilocular ovary of B. aptera (B), with a fertile ovule and the placental sept that divides the locule. Scale = 200 μm. fo, fertile ovule; lo, locule; se, septum; fu, funicule ovule. Fruits were collected during the initial stage of development (n = 50 fruits per three trees per species) and fixed with FAA. Fruits were dissected and grouped into three categories (fruits with ovule or embryo in development; fruits with aborted ovules, occupied by insects; and fruits with aborted ovules, unoccupied). Photographs were taken with bright-field illumination.

The characteristic of dry fruits is the absence of an embryo. The remains of an aborted ovule and/or endocarp malformations were found inside these dry fruits. At least one of the valves remains strongly attached to the rest of the fruit. Immature fruits with all the ovules aborted were seen during the three stages of development. These fruits were undetectable at first sight as they show the same morphological characteristics as immature fruits with a developing embryo.

Fruit structure

Once the fruit has reached its final size, the wall of the ovary shows an exocarp, a mesocarp and an endocarp (Fig. 2A), and the next changes correspond to tissue differentiation. The exocarp is parenchymatous, consisting of a cuticle, a monostratified epidermis and a pluristratified subepidermis (Fig. 2B). During this stage, the mesocarp has two layers; the external one is parenchymatic, characterized by the presence of resin canals associated with vascular bundles (Fig. 2C). The internal mesocarp consists of a series of 5–10 small cells (depending on the species), which conform to the dehiscent zone of the fruit, and that originate the pseudoaril when they divide. This division was more evident in species with an incomplete pseudoaril. The internal mesocarp and the endocarp are separated by a stratum of cells with calcium oxalate crystals (Fig. 2D). The endocarp consists of several strata of sclerenchymatous cells which become enlarged, lose their content and rapidly widen the walls; we then have a stratum of parenchymatic cells and, finally, we see the pluristratified internal epidermis (Fig. 2D). The structural characteristics of the ovary walls in immature fruits with an aborted ovule were the same as those described above; therefore, the presence of tissues with no indication of abscission, and the absence of a seed confirm the phenomenon of parthenocarpy in all the species.

Fig. 2.

Cross-sections of the ovary of Bursera during the initial stage of development. (A) Wall of the pericarp of B. biflora with the general characteristics of 12 studied species; scale = 200 μm. (B) Exocarp of B. arida; scale = 25 μm. (C) Mesocarp of B. schlechtendalii; scale = 100 μm. (D) Endocarp and mesocarp of B. submoniliformis, the oval indicates the area where the internal mesocarp divides to give way to the pseudoaril; scale = 100 μm. Abbreviations: ex, exocarp; me, mesocarp; en, endocarp; rc, resiniferous canal; vb, vascular bundles; dz, dehiscence zone; tr, trichome; cu, cuticle; ep, epidermis; sep, subepidermis; pc, parenchymatic cells; ps, pseudoaril; cc, crystalliferous cells. Fruits were collected during the initial stage of development (n = 50 fruits per three trees per species), and fixed with FAA. Photographs were taken with bright-field illumination in (A), (B) and (D), and phase-contrast illumination in (C).

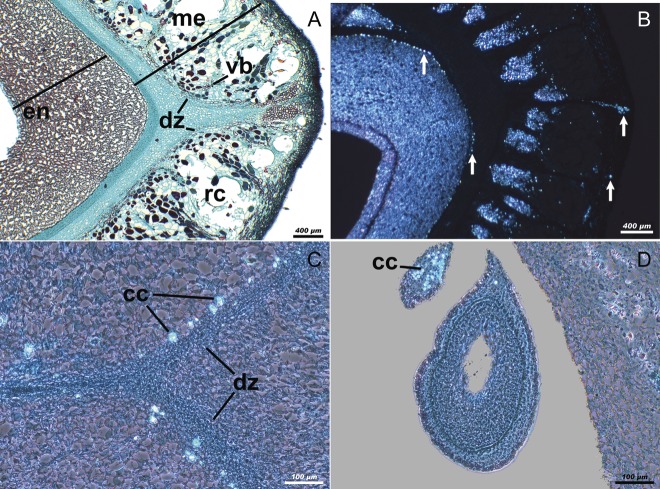

Cells with secondary walls on the exocarp and endocarp were seen during the intermediate stage. Also seen was the production of calcium oxalate crystals in different areas of the ovary (Fig. 3A). The disposition and amount of crystals were different depending on the species as well as the presence/absence of a developing ovule (Table 4). Nevertheless, it was possible to see them in the area of union of the carpels attached, the subepidermis and to the most internal stratum of the mesocarp in all the species (Fig. 3B). Other zones with crystals were the external mesocarp, dehiscent area (Fig. 3C), funicule of the viable ovule, placental sept, viable ovule and abortive ovules (Fig. 3D). Most crystals were found in the placental sept and the funicule of the ovule, but in some of the species, like B. copallifera and B. fagaroides, they were seen in the external mesocarp, while in other species, like B. aptera and B. glabrifolia, they were found in the dehiscent area or in the internal mesocarp. The viable fruits (with a developing ovule) in B. bicolor, B. copallifera and B. schlechtendalii had crystals in the abortive ovules. The amount of crystals was very small during the initial stage of development and they would usually be on their own; nevertheless, during the intermediate stage, small groups of about five or six crystals, and sometimes even more, were seen. Fewer crystals were seen in parthenocarpic fruits of all species in relation to the density of the fruits with seed (Table 4). In viable fruits of B. arida, the larger crystals were seen in the subepidermis and the external mesocarp, and sometimes they were invading the internal mesocarp (Fig. 4A), while no crystals were seen in parthenocarpic fruits.

Fig. 3.

Cross-section of the ovary of Bursera during the intermediate stage. (A) Pericarp of B. grandifolia showing cells with secondary walls; scale = 400 μm. (B) Pericarp of B. copallifera showing the disposition of the calcium oxalate crystals (arrows) found in 12 studied species; scale = 400 μm. (C) Crystals in the dehiscence area of B. glabrifolia; scale = 100 μm. (D) Abortive ovules of B. schlechtendalii; scale = 100 μm. ex, exocarp; me, mesocarp; en, endocarp; rc, resiniferous canal; dz, dehiscence zone; cc, crystalliferous cells. Fruits were collected during the intermediate stage of development (n = 50 fruits per three trees per species) and fixed with FAA. Photographs were taken with bright-field illumination in (A), cross-polarized light illumination in (B) and phase-contrast illumination in (C) and (D).

Table 4.

Distribution and amount of calcium oxalate crystals in fruits with seeds (S) and parthenocarpic fruits (P), in the intermediate stage of maturation. They are represented by the presence and proportion of crystals in each structure: (+) solitary or in pairs, (++) in groups of four to six, (+++) in groups of more than seven crystals. Fruits were collected during the intermediate development stage (n = 50 fruits per three trees per species) and fixed in FAA. Slices were viewed with cross-polarized light illumination and phase-contrast illumination. At least three repetitions were made for each type of fruit for each species.

| Species | Outer mesocarp |

Dehiscence zone |

Septum |

Ovule funicule |

Viable ovule |

Aborted ovules |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | P | S | P | S | P | S | P | S | S | P | |

| B. aptera | ++ | + | ++ | − | ++ | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| B. arida | ++ | + | − | − | +++ | + | ++ | + | − | − | + |

| B. bicolor | − | − | − | − | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| B. biflora | − | − | − | − | ++ | + | ++ | + | − | − | − |

| B. bipinnata | ++ | − | − | − | ++ | + | ++ | + | + | − | − |

| B. copallifera | ++ | ++ | − | − | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| B. fagaroides | ++ | − | − | − | ++ | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. glabrifolia | ++ | − | ++ | − | +++ | ++ | + | + | − | − | − |

| B. grandifolia | − | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | − | − | − |

| B. lancifolia | + | − | ++ | − | +++ | − | ++ | + | − | − | − |

| B. schlechtendalii | + | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ |

| B. submoniliformis | − | − | − | − | +++ | + | +++ | − | − | − | − |

Fig. 4.

(A) Group of calcium oxalate crystals (druses), accompanied by tannins on the exocarp and external mesocarp of B. arida during the dispersal stage; scale = 50 μm. (B) Sclerenchymatic cells associated with vascular bundles on the mesocarp of B. bipinnata; scale = 200 μm. (C) Cell of multilaminated wall of the lignified endocarp of B. aptera; scale = 1 μm. Abbreviations: me, mesocarp; sep, subepidermis; en, endocarp; d, druses; tc, tanniniferous cells; ps, pseudoaril; sc, sclerenchymatic cells; dz, dehiscence zone; rc, resiniferous canal; is, intracellular space; mw, multilamellar wall. Fruits were collected during the final development stage (n = 50 fruits per three trees per species). In (A) and (B), the fruits were fixed with FAA and imbibed in paraffin; photographs were taken with bright-field illumination. In (C), fruits were dried to a critical point and covered in gold, SEM micrograph.

While the viable ovule remains with no apparent changes, groups of sclerified cells, associated with the vascular bundles, were seen in the internal mesocarp (Fig. 4B). The endocarp lignifies, forming a very hard structure that consists of a network of cells with a very thick multi-laminated wall that strongly reduces the cell light (Fig. 4C). The endocarp's hardness is tightly related to the presence of the embryo, and it is this tissue that provides the necessary protection to the seed, as the testa is soft tissue and can easily be broken (Fig. 5). During the dispersal stage, the exocarp and the external mesocarp separate from the rest through the dehiscence zone, which permits sight of the pseudoaril, which can be seen in trees and is part of the pericarp enclosing the seed. The exposed portion of the endocarp, extremely hard and bright black even in fruits with an incomplete pseudoaril, can be seen.

Fig. 5.

(A) Fruit of B. arida with a developing embryo; scale = 100 μm. (B) Higher magnification of the box marked in (A), showing the detail of the seed's cover; scale = 10 μm. Abbreviations: em, embryo; sco, seed coat; en, endocarp. Fruits were collected during the final development stage (n = 50 fruits per three trees). Fruits were dried to a critical point and covered in gold, SEM micrographs.

Two patterns related to the development of the endocarp were found in parthenocarpic fruits. In the first one, the cells of the endocarp multiply in an abnormal fashion. Subsequently, they enlarge, filling the locule and crushing the viable or the aborted ovule; only some areas lignify and develop a relatively hard tissue (Fig. 6A). On the contrary, lignification of the endocarp of a viable fruit in a similar or later stage of development complicates the histological processing of the sample; therefore, the pericarp and the delimitation of the layers is better seen with a SEM (Fig. 6B). In the second development pattern of the endocarp in a parthenocarpic fruit, the cells of the endocarp collapse and originate a soft tissue even in the first stages of development (Fig. 6C), contrasting with the cell organization of the viable fruit (Fig. 6D). In both cases of abortion of the ovule, the mesocarp and exocarp showed the same characteristics as the viable fruit (Fig. 6B and D). No starch was found in the tissues; the cuticles had cutine and suberine. Complex carbohydrates and proteins were found distributed along the wall of the ovary during the initial stage of development of all fruits. When the viable fruit starts maturing, the endocarp consists of lignin and proteins. Nevertheless, in parthenocarpic fruits, the absence of lignin produces a much softer protein-rich tissue (Fig. 6E and F).

Fig. 6.

(A) Proliferation of the endocarp filling the locule in the parthenocarpic fruit of B. arida; scale = 400 μm; safranin–fast green staining. (B) Viable fruit of B. schlechtendalii with a developing ovule and normal pericarp; scale = 1 mm. (C) Parthenocarpic fruit of B. lancifolia with a collapsed endocarp and infertile ovules; scale = 200 μm. (D) Viable fruit of B. bicolor in early development stages. (E and F) Result of the lignin test on the parthenocarpic fruit (E) and viable fruit (F) of B. arida, the positive result in (F) is characterized by the strongly black-tinted cell walls. Abbreviations: enp, proliferation of endocarp; lo, locule; fo, fertile ovule; io infertile ovule; me, mesocarp; ps, pseudoaril; en, endocarp; l-en, lignified endocarp. Fruits were collected during the initial and intermediate stages of development (n = 50 fruits per three trees per species), and fixed with FAA. Fruits were dissected and grouped into three categories (fruits with ovule or embryo in development, and fruits with aborted ovule, occupied, or not, by insects). For the lignin test in (C) and (D), we used phloroglucinol-HCl previously deparaffinated with gradual ethanols (López et al. 2005). Photographs were taken with bright-field illumination in (A), (C), (E) and (F); photographs of scanning microscopy (15× to 200 000×) in (B) and (D).

Tannins were found in all of the species, their distribution and amount varied in relation to the species and the age of the fruit. These are produced during the latency stage of the fruit, mainly in the subepidermis, the external mesocarp and the ovule, and persist during the dispersal stage. Species in Group B had more tannins than those in Group A. This difference was also seen among the types of fruits produced, as the parthenocarpic fruits had much less tannins than those with seeds. In fact, no tannins were found in parthenocarpic fruits of B. aptera. The apparent latency of the ovule is interrupted and it is possible to see embryos in the first stages of development; this was seen mainly during the dispersal stage in fruits that were still indehiscent but whose colouration indicated they were near maturation, i.e. when the green exocarp started acquiring a reddish (in most species), purple (in B. fagaroides) or orange–yellow (in B. aptera) colouration. During the same stage, fruits in Group B had an abnormally developed endocarp and an ovule with not enough space to develop after its activity had re-initiated. These results indicate that fruits of all species develop while the ovule remains in an apparent state of latency.

Fruits and insects

All species had parthenocarpic fruits; the proportion varied between species, and no general pattern between production and maturation stage was found (Table 5). In B. arida, B. biflora and B. grandifolia, the proportion of parthenocarpic fruits increased from the first stage to the third. In B. aptera, B. schlechtendalii, B. copallifera, B. lancifolia and B. bicolor, the percentage of fruits increased during the second stage compared with the first stage, but decreased during seed dispersal, while in B. fagaroides, B. bipinnata and B. glabrifolia, the opposite pattern was seen. Finally, in B. submoniliformis, the percentage of these fruits showed a decreasing tendency.

Table 5.

Average percentage of parthenocarpic fruits with/without insects recorded during the initial, intermediate and final development stages. Species were arranged by group, and the percentage of parthenocarpic fruits without insects during the initial stage. Fruits were collected and fixed in FAA (n = 50 fruits per tree per species per stage). Collection took place during the 2010–2011 fructification season.

| Stage | Initial |

Middle |

Final |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without insects | Occupied by insects | Without insects | Occupied by insects | Without insects | Occupied by insects | |

| B. aptera | 42.68 | 0.64 | 45.54 | 0.59 | 14.62 | 0.66 |

| B. fagaroides | 14.9 | 0 | 9.84 | 0 | 12.66 | 1.33 |

| B. arida | 7.94 | 0 | 23.94 | 0 | 26.66 | 0 |

| B. schlechtendalii | 1.79 | 0 | 3.34 | 0.95 | 1.33 | 0 |

| B. bipinnata | 13.79 | 13.79 | 5.45 | 3.63 | 7.9 | 3 |

| B. glabrifolia | 8 | 0 | 5.17 | 0 | 11.74 | 2.26 |

| B. submoniliformis | 6.01 | 6.01 | 3.73 | 0 | 2.87 | 0 |

| B. copallifera | 3.69 | 3.69 | 15.83 | 1.6 | 4.33 | 0 |

| B. lancifolia | 2.61 | 0 | 11.59 | 2.89 | 7.9 | 0 |

| B. biflora | 0.53 | 0 | 11.31 | 0 | 41.35 | 0 |

| B. bicolor | 0 | 0 | 6.89 | 0 | 6.33 | 0 |

| B. grandifolia | 0 | 0 | 1.56 | 0 | 5.13 | 0 |

The four species with fruits unoccupied by insects were B. arida, B. bicolor, B. biflora and B. grandifolia. Three species of Group B had fruits with insects. These fruits were parthenocarpic and full of tissue, and abortion of the ovule took place before occupation by insects as in some cases the ovule was intact, immersed in the tissue or else had stopped its development during the very early stages (Fig. 7). Also, five species of Group A had insects in some stage of development. All of these fruits had an aborted ovule; nevertheless, during the initial and intermediate stages, it was impossible to determine whether the abortion had been caused by an insect or had taken place before insect occupation. In the following data interpretation, we assume that these fruits were parthenocarpic because the walls of the ovary had the characteristics described above. The insects found were wasps in the three stages: larvae, pupae and adults (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea), as well as pupae of coleoptera (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae).

Fig. 7.

Fruits of Bursera occupied by insects (arrowheads). (A) Fruit of B. aptera with two pairs of aborted ovules (arrows), indicating an abortion during the very early stages of development. (B) Fruit of B. aptera with the locule full of tissue and an adult wasp in its interior. (C) Fruit of B. bipinnata with a pupa of a beetle; the line indicates the width of the cocoon. Scale = 1 mm. Fruits were collected during the initial stage (B. bipinnata) and final stage of development (B. aptera, n = 50 fruits per three trees). Fruits were dried to a critical point and covered with gold, SEM photographs.

The average number of occupied fruits was below or the same as the proportion of unoccupied fruits in the three stages (Table 5). In species of Group A (except B. glabrifolia), occupation was higher during the initial stage, while species in Group B had more insects towards the dispersion stage. In B. schlechtendalii, a wasp larva was found during the intermediate stage. This larva was in a state of decomposition in the mesocarp; the ovule and the lignified endocarp looked undamaged. This phenomenon was also seen in B. bipinnata during the dispersal stage, a fact which suggests that the lignified endocarp is one of the strongest defenses against insects.

Discussion

Fruiting phenology

The phenology of the studied species was very similar to that of B. morelensis and other species of trees typical of dry seasonal tropical forests (Bullock and Solís-Magallanes 1990; Borchert et al. 2004; Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008). The development of the fruit showed the same pattern described for B. morelensis and Canarium oleosum (Wannan and Quinn 1990; Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008), in which only the locule that will contain the seed develops. The results suggest that the lack of synchronicity between the development of the ovary and the development of the seed is another characteristic of the genus Bursera, as this takes place in the 12 studied species, besides B. delpechiana, B. medranoana and B. morelensis (Srivastava 1968; Cortes 1998; Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008).

Structure

The structure and differentiation of the pericarp of Bursera show an immense similarity to those of the genus Commiphora published by Van der Walt (1975), suggesting a morphologic sinapomorphy. Nevertheless, ontogenetic studies are necessary to demonstrate this (Thulin et al. 2008; Daly et al. 2011). The resiniferous canals associated with the vascular bundles in the external mesocarp are a characteristic shared by the 12 species and by Canarium oleosum (Wannan and Quinn 1990). The endocarp with sclereids is also a characteristic of C. oleosum, Spondiadoideae and Anacardioideae (Anacardiaceae), supporting Wannan and Quinn (1990), who suggested that it is a plesiomorphic characteristic in the Anacardiaceae family.

From a structural point of view, the viable and parthenocarpic fruits of Bursera are similar, as is the case with Schinopsis balansae (Anacardiaceae) (González and Vesprini 2010). Nevertheless, the difference with our study lies in the observation that the parthenocarpic fruits keep the characteristics of the immature fruits, such as the soft tissue with a high availability of nitrogen compounds, and a limited production of secondary metabolites.

According to Dickie and Stuppy (2003), besides its mechanical purpose, the seed cover, or a part of it, can develop structures that will help dispersion, such as a brightly coloured pulp (aril) that will attract dispersers. Results indicate that the protective role of the testa has been transferred to the endocarp, like in Anacardiaceae (Corner 1976; Wannan and Quinn 1990), and the attractive tissue is the pseudoaril, thus named because it is part of the fruit and not of the seed (Font-Quer 1953). As a consequence, the unit of dispersion of the species studied consists of the seed, the endocarp and the pseudoaril or internal mesocarp. No external differences between the immature viable fruits and the immature perthenocarpic fruits were found. Nevertheless, the data indicate that the exposed pseudoaril is a sign of maturity of the seed, as suggested by Andrés-Hernández and Espinosa-Organista (2002), apart from being a characteristic of the viability of the fruit, like in B. morelensis (Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008; Ramos-Ordoñez and Arizmendi 2011).

Bursera glabrifolia provided an interesting piece of information: two-thirds of its pseudoaril, sometimes all of it, covering the pyrene, the same as in the Copallifera group in which B. submoniliformis, B. bipinnata, B. bicolor and B. copallifera are found (Becerra 2003). Molecular phylogeny assembles B. glabrifolia with B. biflora, and other species, in the Glabrifolia group, in which less than two-thirds of the pyrene is covered by the pseudoaril (Becerra 2003). Toledo (1982) included the pseudoaril as a taxonomic character in a study of the species in the state of Guerrero, México; thus, in this context, it would be useful to do a revision of the morphological characteristics that fit the most recent results on the phylogeny of the genus (De-Nova et al. 2012).

Parthenocarpy

Results show that parthenocarpy might be a common phenomenon in Bursera and can take place during any stage of development, as has been suggested by Ramos-Ordoñez et al. (2008) and Srivastava (1968). It is also possible that parthenocarpy is a plesiomorphic character present in a common ancestor of both the Burseraceae and the Anacardiaceae families, selected for an unknown reason, and that has remained thus to this day (Verdú and García-Fayos 1998; Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008). The abortion of the ovule and the absence of tissue in the locule seen in species with short ripening or maturation periods are very similar to those of Pistacia lentiscus, another parthenocarpic species of the Anacardiaceae family in which fruits with remains of the funicule or of aborted embryo have been reported (Jordano 1988). The abnormal development of the pericarp, common in species with longer periods of maturation or ripening, coincides with what has been described for B. morelensis (Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008). This phenomenon is well known in artificially manipulated crops such as citrus plants. Parthenocarpy could therefore be related to a hormonal imbalance, as is the case with such crops (Gillaspy et al. 1993; Varoquaux et al. 2000).

Insects and fruits

The presence of insects in the fruits seems to be related to diminished physical and chemical defenses as well as to nutrient availability; both of these factors are also influenced by the period of time the fruits take before they mature. The tannins, lignin and calcium oxalate crystals are known to reduce the palatability of the tissues, inhibit the digestion of carbohydrates, reduce the growth rate of many insects and harden plant tissues (Franceschi and Horner 1980; Rosenthal and Berenbaum 1991; Weeb 1999; Molano-Flores 2001; Strauss and Zangerl 2002). For many plant species, therefore, predation of fruits and/or seeds by insects is related to scarce chemical and physical defenses (Zangerl et al. 1991; Hulme and Benkman 2002). In addition, species that retain their fruits for long periods of time have more defences than those species with short maturation periods (Stiles 1980). All this would explain why more insects were found during the first stages of development and in parthenocarpic fruits. It also explains the variation found in the production of secondary metabolites between the initial stage and the intermediate stage, and why the species of Group A had less tannins those in Group B.

Those insects that did not trespass into the lignified endocarp have already been described in another study on B. morelensis (Barranco-Salazar 2011). In that study, the endocarp moved inwards, reducing the locule, which had the embryo with no indications of abortion. The space left by the movement was occupied by a larva that fed on the mesocarp. This suggests that the lignified endocarp of Bursera is the best, and maybe the last, defence against insect predation during the development of the embryo.

Because of the scarce information on Neo Tropical phytofagous entomofauna (V. Hernández-Ortiz, Instituto de Ecología A.C. México, pers. commun.), as well as the small number of specimens obtained, we can only speculate on the possible interactions of the insects found. The superfamily Chalcidoidea is characterized for grouping a large number of parasitoid insects (Gencer 2004). Nevertheless, in this and other studies on Bursera (Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008; Barranco-Salazar 2011), no evidence has been found on wasps as parasites of another insect inside the fruit. There is the possibility that, when they do not find their primary food, the parasitoid eats other resources (Fletcher et al. 1994) such as the embryo and/or pericarp of Bursera (Barranco-Salazar 2011). The availability of nitrogenated compounds in immature and parthenocarpic fruits of Bursera could mean they are a food resource for the larvae until they become adults (Saiz et al. 1987). This result could also explain why granivorous birds eat parthenocarpic fruits of B. morelensis (Ramos-Ordoñez and Arizmendi 2011), as the removal of these fruits coincides with the reproductive stage of the birds, just when the protein demand is high (Ramos-Ordoñez 2009; Barranco-Salazar 2011).

The results do not enable us to determine whether seed predation by insects is reduced by the production of parthenocarpic fruits, as is the case with other plants (Coetzee and Giliomee 1987; Zangerl et al. 1991; Traveset 1993; Ziv and Bronstein 1996; Verdú and García-Fayos 2001; Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2008). We suggest a detailed monitoring to determine the time intervals in the development, as well as enlarging the fruit sample, as our sample (50 fruits per three trees per species) is small if one considers that individual trees can produce harvests that range from a few hundred to several thousand fruits (Ramos-Ordoñez et al. 2010), and that populations can be very abundant. In species of Group A, in particular, it is necessary to carry out experiments that exclude the insects, in order to determine the real proportion of parthenocarpic fruits produced and occupied.

Birds feeding on fruits were seen in both study sites, suggesting there is a plant–bird interaction. It is important to examine whether this interaction plays an important role in the reproduction of the different species, as has previously been seen in B. morelensis, as well as the effect of endozoochory in germination, and of parthenocarpy in the removal of fruits (Ramos-Ordoñez 2009; Barranco-Salazar 2011; Ramos-Ordoñez and Arizmendi 2011). It is also important to determine whether the presence of insects in the fruits has negative effects in dispersion by frugivorous animals (Jordano 1987; Garcia et al. 1999). In spite of being adapted for dispersion by birds, many seeds fall to the ground (barochory), increasing the possibility of secondary dispersion as another important mechanism by which the seeds are taken to favourable sites for their germination. It is necessary to determine which animal species participate in this process, and what their contribution is in the establishment of the seedlings, a key process in dry tropical seasonal forests (Verdú and Valiente-Banuet 2008). This information will help us to understand the intricate web of processes that are needed to sustain a plant community, and will contribute to ecological restoration plans, as is the case with other species (Fink et al. 2009; Heleno et al. 2010; Howe et al. 2010).

Conclusions and forward look

The anatomical description of the fruit helps one to better understand the phylogenetic relationship between the Burseraceae and the Anacardiaceae families, while the phenological characteristics of the maturation process constitute a useful tool in future studies of ecological aspects such as germination and seed dispersal. The presence of insects in fruits of eight of the 12 species seems to be related to the structural characteristics of immature and parthenocarpic fruits. Nevertheless, a more detailed analysis of this interaction is necessary. Parthenocarpy is represented in the two sections into which the genus Bursera is divided; production of seedless fruits is energy saving for the plant because, on the one hand, it takes place during the early stages of development and, on the other, the production of defence structures and compounds stops. In this context, we need further studies that will determine the ecological role of these fruits and their impact on the reproductive success of the species.

Sources of funding

Financial support was provided by the internal budget of the Laboratorio de Desarrollo de Plantas to J. Márquez-Guzmán, Facultad de Ciencias, PAPIIT IN217511-3 project to M. C. Arizmendi, FES Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA, UNAM) postdoctoral fellowship to M. F. Ramos-Ordoñez.

Contributions by the authors

All the authors contributed to a similar extent overall.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dra. Silvia Espinosa and Master in Photography. Ana Isabel Bieler from the Laboratory of Microscopía Electronica de Barrido and Microcine, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for microscopy technical assistance. We thank Master in Sciences. R. Wong, M. en C. M. Pérez-Pacheco, Biologist M. Espinosa-Sanchez and Biol. S. Gómez-Sanchez for their technical assistance. We thank Biol. C. Machuca and M. López-Carrera for assistance in the field. We thank two anonymous reviewers for the revision of an earlier draft of the manuscript. We thank J. Bain for text translation.

References

- Andrés-Hernández AR, Espinosa-Organista D. Morfología de plántulas de Bursera Jacq. ex L. (Burseraceae) y sus implicaciones filogenéticas. Boletin de la Sociedad Botánica de México. 2002;70:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelier J, Endress P. Comparative floral morphology and anatomy of Anacardiaceae and Burseraceae (Sapindales), with a special focus on gynoecium structure and evolution. American Journal of the Linnean Society. 2009;159:499–571. [Google Scholar]

- Barranco-Salazar A. Dispersores potenciales de Bursera morelensis en Santa María Tecomavaca, Oaxaca, México. México: Tesis de Licenciatura, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra JX. Evolution of Mexican Bursera (Burseraceae) inferred from ITS, ETS, and 5S nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2003;26:300–309. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(02)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra JX. Timing the origin and expansion of the Mexican tropical dry forest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2005;102:10919–10923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409127102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra JX, Venable DL. Sources and sinks of diversification and conservation priorities for the Mexican tropical dry forest. PLoS ONE. 2008 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003436. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfil-Sanders C, Cajero-Lázaro I, Evans RY. Germinación de semillas de seis especies de Bursera del centro de México. Agrociencia. 2008;42:827–834. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert R, Meyer SA, Felger RS, Porter-Bolland L. Environmental control of flowering periodicity in Costa Rican and Mexican tropical dry forests. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2004;13:409–425. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock SH, Solís-Magallanes A. Phenology of canopy trees of a tropical deciduous forest in Mexico. Biotropica. 1990;22:22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccon E, Hernández P. Seed rain dynamics following disturbance exclusion in a secondary tropical dry forest in Morelos, Mexico. Revista De Biologia Tropical. 2009;57:257–269. doi: 10.15517/rbt.v57i1-2.11319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee JH, Giliomee JH. Seed predation and survival in the infructescences of Protea repens (Proteaceae) The South African Journal of Botany. 1987;53:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Corner EJH. The seeds of dicotyledons. London: Cambridge University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes A. Biología reproductiva de Bursera medranoana Rzedowski & Ortiz (Burseraceae), una especie de origen híbrido. México: Tesis de Licenciatura, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Daly DC, Harley MM, Martínez-Habibe MC, Weeks A. Burseraceae. In: Kubitzki K, editor. Flowering plants. Eudicots. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 76–104. [Google Scholar]

- De-Nova JA, Medina R, Montero JC, Weeks A, Rosell JA, Olson ME, Eguiarte LE, Magallón S. Insights into the historical construction of species-rich Mesoamerican seasonally dry tropical forests: the diversification of Bursera (Burseraceae, Sapindales) New Phytologist. 2012;193:276–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickie JB, Stuppy WH. Seed and fruit structure: significance in seed conservation operations. In: Smith RD, Dickie JB, Linington SH, Pritchard HW, Probert RJ, editors. Seed conservation: turning science into practice. London: The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; 2003. pp. 252–279. [Google Scholar]

- Esau K. Anatomía vegetal. 3rd edn. Barcelona: Omega; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández N. Análisis de la dinámica de comunidades vegetales con relación a la evolución del paisaje en la zona semiárida de Coxcatlán, Puebla. Caso: Abanico aluvial de la Barranca del Muchil. México: Tesis de Maestría, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fink RD, Lindell CA, Morrison EB, Zahawi RA, Holl KD. Patch size and tree species influence the number and duration of birds visits in forest restoration plots in Southern Costa Rica. Restoration Ecology. 2009;17:479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JP, Hughes JP, Harvey I. Life expectancy and egg load affect oviposition decisions of a solitary parasitoid. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences. 1994;258:163–167. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font-Quer P. Diccionario de botánica. Barcelona, Spain: Labor; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi VR, Horner HT. Calcium oxalate crystals in plants. Botanical Review. 1980;46:361–427. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D, Zamora R, Gomez JM, Hodar JA. Bird rejection of unhealthy fruits reinforces the mutualism between juniper and its avian dispersers. Oikos. 1999;85:536–544. [Google Scholar]

- Gencer L. A study on the chalcidoid (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) parasitoids of leafminers (Diptera: Agromyzidae) in Ankara Province. Turkish Journal of Zoology. 2004;28:119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gillaspy G, Ben-David H, Gruissem W. Fruits: a developmental perspective. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1439–1451. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.10.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Garzón A. Caracterización del medio físico de la cuenca del río Tembembe empleando sistemas de información geográfica. México: Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua; 2002. Laboratorio de Sistemas de Información Geográfica del SIG CUENCAS. [Google Scholar]

- González AM, Vesprini JL. Anatomy and fruit development in Schinopsis balansae (Anacardiaceae) Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid. 2010;67:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Guízar-Nolazco E, Sánchez-Vélez A. Guía para el reconocimiento de los principales árboles del Alto Balsas. México: Universidad Autónoma Chapingo; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Heleno R, Lacerda I, Ramos JA, Memmott J. Evaluation of restoration effectiveness: community response to the removal of alien plants. Ecological Applications. 2010;20:1191–1203. doi: 10.1890/09-1384.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe H, Westley LC. Ecological relationships of plants and animals. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Howe HF, Urincho-Pantaleon Y, de la Peña-Domene M, Martínez-Garza C. Early seed fall and seedling emergence: precursors to tropical restoration. Oecologia. 2010;164:731–740. doi: 10.1007/s00442-010-1669-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme PE, Benkman CW. Granivory. In: Herrera CM, Pellmyr O, editors. Plant–animal interactions: an evolutionary approach. Blackwell: Oxford; 2002. pp. 132–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jordano P. Avian fruit removal: effects of fruit variation, crop size, and insect damage. Ecology. 1987;68:1711–1723. doi: 10.2307/1939863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordano P. Polinización y variabilidad de la producción de semillas en Pistacia lentiscus L. (Anacardiaceae) Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid. 1988;45:213–231. [Google Scholar]

- López CML, Márquez J, Murguía G. Técnicas para el estudio del desarrollo en angiospermas. 2 edn. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Medina JS. Determinación del vigor reproductivo de Stenocereus stellatus (Cactaceae) a lo largo de una cronosecuencia edáfica en un abanico aluvial en Coxcatlán, Valle de Tehuacán. México: Tesis de Licenciatura, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Molano-Flores B. Herbivory and concentrations affect calcium oxalate crystal formation in leaves of Sida (Malvaceae) Annals of Botany. 2001;88:387–391. [Google Scholar]

- Myers N, Mittermeier R, Mittermeier C, da Fonseca G, Kent J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 2000;403:853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Ordoñez MF. México: 2009. Dispersión biótica de semillas y caracterización de los frutos de Bursera morelensis en el Valle de Tehuacan, Puebla. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Ordoñez MF, Arizmendi MC. Parthenocarpy, attractiveness and seed predation by birds in Bursera morelensis. Journal of Arid Environments. 2011;75:757–762. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Ordoñez MF, Márquez-Guzmán J, Arizmendi MC. Parthenocarpy and seed predation by insects in Bursera morelensis. Annals of Botany. 2008;102:713–722. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Ordoñez MF, Márquez-Guzmán J, Arizmendi MC. Parthenocarpy and seed production in Burseraceae. In: Ramawat KG, editor. Desert plants. Biology and biotechnology. Berlin: Springer; 2010. pp. 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal GA, Berenbaum MR. Herbivores: their interaction with secondary plant metabolites. New York: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rzedowski J, Medina R, Calderón G. Las especies de Bursera (Burseraceae) en la cuenca superior del Río Papaloapan (México) Acta Botanica Mexicana. 2004;66:23–151. [Google Scholar]

- Rzedowski J, Medina R, Calderón G. Inventario del conocimiento taxonómico, así como de la diversidad y del endemismo regionales de las especies mexicanas de Bursera (Burseraceae) Acta Botanica Mexicana. 2005;70:85–111. [Google Scholar]

- Saiz F, Daza M, Casanova D. Relaciones fenológicas entre Pseudopachymerina spinipes (Bruchidae) y Acacia caven (Leguminosae) Anales del Museo de Historia Natural de Valparaíso. 1987;18:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Azofeifa A, Portillo-Quintero C. Extent and drivers of change of neotropical seasonally dry forests. In: Dirzo R, Young H, Mooney H, Ceballos G, editors. Seasonally dry tropical forests. Ecology and conservation. Washington, USA: Island Press; 2011. pp. 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava GN. Male and female gametophytes and development of the seeds in Bursera delpechiana Poiss. Journal of the Indian Botanical Society. 1968;47:53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles EW. Patterns of fruit presentation and seed dispersal in bird-disseminated woody plants in the eastern deciduous forest. American Naturalist. 1980;116:670–685. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SY, Zangerl AR. Plant–insect interactions in terrestrial ecosystems. In: Herrera CM, Pellmyr O, editors. Plant–animal interactions: an evolutionary approach. Blackwell: Oxford; 2002. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Thulin M, Beier BA, Razafimandimbison SG, Banks HI. Ambilobea, a new genus from Madagascar, the position of Aucoumea, and comments on the tribal classification of the frankincense and myrrh family. Nordic Journal of Botany. 2008;26:218–229. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo C. El género Bursera en el estado de Guerrero. México: Tesis de Licenciatura, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Traveset A. Deceptive fruits reduce insect seed predation in Pistacia terebinthus L. Evolutionary Ecology. 1993;7:357–361. [Google Scholar]

- Traveset A. Consecuencias de la ruptura de mutualismos planta-animal para la distribución de especies vegetales en las Islas Baleares. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural. 2002;75:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Pijl L. Principles of dispersal in higher plants. Berlin: Springer; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Walt J. The fruit of Commiphora. Boissiera. 1975;24:325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Varoquaux F, Blanvillain R, Delseny M, Gallois P. Less is better: new approaches for seedless fruit production. Trends in Biotechnology. 2000;18:233–242. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(00)01448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Yanes C, Batis-Muñoz AI, Alcocer-Silva MI, Gual-Díaz M, Sánchez-Dirzo C. Árboles y arbustos potencialmente valiosos para la restauración ecológica y la reforestación. México: CONABIO-Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Verdú M, García-Fayos P. Ecological causes, function, and evolution of abortion and parthenocarpy in Pistacia lentiscus (Anacardiaceae) Canadian Journal of Botany. 1998;76:134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Verdú M, García-Fayos P. The effect of deceptive fruits on predispersal seed predation by birds in Pistacia lentiscus. Plant Ecology. 2001;156:245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Verdú M, Valiente-Banuet A. The nested assembly of plant facilitation networks prevents species extinctions. The American Naturalist. 2008 doi: 10.1086/593003. doi:10.1086/593003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannan B, Quinn C. Pericarp structure and generic affinities in the Anacardiaceae. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 1990;102:225–252. [Google Scholar]

- Weeb MA. Cell-mediated crystallization of calcium oxalate in plants. The Plant Cell. 1999;11:751–761. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.4.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangerl AR, Berenbaum MR, Nitao JK. Parthenocarpic fruits in wild parsnip: decoy defence against a specialist herbivore. Evolutionary Ecology. 1991;5:136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ziv Y, Bronstein JL. Infertile seeds of Yucca schottii: a beneficial role for the plant in the yucca–yucca moth mutualism? Evolutionary Ecology. 1996;10:63–76. [Google Scholar]