Abstract

Worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is approximately 50%, with the highest being in developing countries. We compared cure rates and tolerability (SE) of second-line anti-H. pylori levofloxacin/amoxicillin (LA)-based triple regimens vs standard quadruple therapy (QT). An English language literature search was performed up to October 2010. A meta-analysis was performed including randomized clinical trials comparing 7- or 10-d LA with 7-d QT. In total, 10 articles and four abstracts were identified. Overall eradication rate in LA was 76.5% (95% CI: 64.4%-97.6%). When only 7-d regimens were included, cure rate was 70.6% (95% CI: 40.2%-99.1%), whereas for 10-d combinations, cure rate was significantly higher (88.7%; 95% CI: 56.1%-109.9%; P < 0.05). Main eradication rate for QT was 67.4% (95% CI: 49.7%-67.9%). The 7-d LA and QT showed comparable efficacy [odds ratio (OR): 1.09; 95% CI: 0.63-1.87], whereas the 10-d LA regimen was significantly more effective than QT (OR: 5.05; 95% CI: 2.74-9.31; P < 0.001; I2 = 75%). No differences were reported in QT eradication rates among Asian and European studies, whereas LA regimens were more effective in European populations (78.3% vs 67.7%; P = 0.05). Incidence of SE was lower in LA therapy than QT (OR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.18-0.85; P = 0.02). A higher rate of side effects was reported in Asian patients who received QT. Our findings support the use of 10-d LA as a simple second-line treatment for H. pylori eradication with an excellent eradication rate and tolerability. The optimal second-line alternative scheme might differ among countries depending on quinolone resistance.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Second-line treatment, Levofloxacin, Quadruple regimen

INTRODUCTION

Since 1982, when Warren and Marshall first discovered Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in the stomach, eradication of the infection has being recognized as crucial for prevention and treatment of gastroduodenal and more recently even extraintestinal diseases[1-4]. The worldwide prevalence of H. pylori infection is approximately 50%, with the highest being in developing countries[5]. Standard first-line therapy consists of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole[6] and achieves successful eradication in up to 80% of patients. During the past decade, an alarming decrease in eradication rates has been observed[7], mostly due to antibiotic resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole[3,8]. Conversely, resistance to amoxicillin and tetracycline remains a rare occurrence worldwide[9-11]. Choice of a second or even third course of therapy is more controversial[6,9,12-14]. Recently, the concept of cumulative eradication rate has been introduced in treatment of H. pylori infection focusing on final cure rate after one or more courses of treatment. In this perspective, if the overall eradication rate is considered even after four consecutive empirical treatments, 99.5% of patients can be cured[15]. Currently, the recommended second-line regimen is a 7-14-d complex scheme consisting of PPI, bismuth, tetracycline and metronidazole[16,17]. However, bismuth salts, applied to decrease bacterial load, are no longer available in many countries[18]. Eradication rate of the quadruple regimen ranges from 65% to 80% and a high incidence of side effects are noted (up to 50% of patients), with consequently poor compliance[19-22]. For this reason, a triple therapy consisting of PPI, metronidazole and amoxicillin or tetracycline for a minimum of 7 d has been recommended as an alternative[6]. Meanwhile, new drugs, such as levofloxacin, rifabutin, furazolidone and azithromycin have been tested in various combinations and doses to overcome falling eradication rates[13,14,23-31].

Among those, levofloxacin-based second-line schemes represent the most promising alternative[32,33]. In particular, association with amoxicillin has been extensively studied, due to rare H. pylori resistance. Currently, a 10-d triple levofloxacin (250 mg BD)/amoxicillin (LA)-based therapy has been recommended as second-line therapy in Italy, and as third-line empirical treatment by European guidelines[6,16]. However, heterogeneity in terms of dosage, combination and duration of treatment do not allow a definitive conclusion.

Moreover, in consideration of differences in quinolone resistance among countries, the ideal second-line treatment for H. pylori infection may differ between areas, countries and races[10,20,34].

Here we compare eradication rates and tolerability exclusively of second-line anti-H. pylori LA-based triple schemes and standard quadruple therapy (QT) in European and Asian studies, in order to guide clinical decision making.

Studies providing information on use of anti-H. pylori LA-based triple therapy and standard quadruple scheme in second-line were identified through a systematic search in the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases by using various combinations of the terms "H. pylori", "levofloxacin", "amoxicillin", "quadruple", "bismuth", "second-line" and "rescue". Additionally, references of retrieved articles were screened for further studies (cross-referencing). We also performed a full manual search of all review articles, recently published editorials and all retrieved original studies presented at Digestive Disease Week, United European Gastroenterology Week, and European Helicobacter Study Group conferences. In addition, reference lists from relevant identified papers were manually searched. All original research articles and abstracts published until the 31 October 2010 were included. The search was limited to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and studies comparing the two regimens (LA vs QT). Two investigators (Di Caro S and Fini L) independently extracted data by using a structured form. Only data from patients undergoing second-line eradication treatments were included in the analysis. There was a > 95% agreement in data extraction between the two investigators.

The following data were extracted from the articles: first author, year of publication, characteristics of study population (sample size, race, sex, age range and mean of study participants), therapy scheme (drugs, duration of treatment, dosage), intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol eradication rates, incidence of side effects, discontinuation due to side effects.

Study outcomes for the meta-analysis were H. pylori eradication and incidence of adverse effects. Sub-analyses were performed comparing 7-d vs 10-d levofloxacin-based regimens in terms of efficacy and adverse events between European and Asian populations. Eradication rate analysis was based on ITT data. In the tolerability analysis, patients who discontinued treatment due to severe side effects were included.

The meta-analysis was performed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses 2009 guidelines. Odds ratio (OR) was used as a measure of association, and summary ORs along with 95% CI were calculated based on a random-effects model using the DerSimonian and Laird methods. Heterogeneity was evaluated to establish if any clinical, methodological, or statistical variability existed among studies included. If significant heterogeneity existed, the random-effects model was used. Also, inconsistency statistic (I2) was calculated to evaluate level of heterogeneity (0%-30%: homogeneity; 30%-50%: moderate heterogeneity; 50%-80%: substantial heterogeneity; > 80%: considerable heterogeneity). A pooled analysis was used to assess differences between levofloxacin regimens (7 d vs 10 d) and study populations. All statistical tests were two-sided and conducted at a significance level of 0.05. Independent academic biostatisticians from Baylor University Medical Center (Daoud Y) performed the statistical analysis. Data were analyzed with Review Manager (RevMan) 5.1 developed by the Cochrane collaboration.

TEN-DAY LEVOFLOXACIN SECOND-LINE SCHEMES DISPLAY SIGNIFICANTLY HIGHER ERADICATION RATE AND LOWER INCIDENCE OF SIDE EFFECTS

Out of 79 titles initially generated by literature searches, 14 studies (10 articles and four abstracts) fulfilling the inclusion criteria were eligible for our analysis. All studies were published from September 2003 to May 2009 and included 677 patients in the LA-based triple therapy group and 608 subjects in the QT group. First-line therapy was a standard triple anti-H. pylori scheme. Tolerability data were available in seven articles. Demographic and clinical data of patients available are reported in Table 1. Studies were divided into two categories based on ethnicity of the study population (Asian and Caucasian population). In all studies, H. pylori infection was determined by 13C urea breath test (UBT), rapid urea test, histology or culture before treatment, and histology and/or 13C-UBT after administration of eradication therapy. Heterogeneity of data available on levofloxacin dose, ranging from 300 mg/d to 1 g/d (Table 1), does not allow a definitive conclusion.

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients, extracted from the published papers (n = 9)

| Ref. | Pts | Days of tp | Test confirming infection | Test confirming eradication |

Age (yr) |

Male (%) |

Smokers (%) |

Clinic (%) |

||||

| L+ A | Q | L + A | Q | L + A | Q | L + A | Q | |||||

| Nista et al[21] | 140 | 10 | UBT and/or biopsy | UBT | 47 ± 10 | 48 ± 10 | 47 | 49 | NA | NA | UD = 37; DD = 33; RD = 30 | UD = 40; DD = 34; RD = 26 |

| Perri et al[29] | 113 | 7 | UBT | UBT | 46 ± 16 | 45 ± 15 | 48 | 47 | 17 | 20 | N = 63; OE = 3; G = 9; GU = 3; D = 10; DU = 9; O = 3 | N = 67; OE = 5; G = 2; GU = 0; D = 19; DU = 5; O = 2 |

| Bilardi et al[39] | 90 (40) | 10 | UBT and/or biopsy | UBT | 56 ± 10 | 54 ± 13 | 30 | 35 | 64 | 52 | NA | NA |

| Gisbert et al[28] | 500 (150) | 7-10 | UBT | UBT | 48 ± 131 | 391 | 231 | FD = 76; DU = 241 | ||||

| Lee et al[80] | 126 (23) | 7 | Rapid urea test | UBT | 50 ± 141 | 631 | 241 | GU = 44; DU = 32; GA = 11; A = 3; F = 1; FD = 9 | ||||

| Wong et al[19] | 106 (61) | 7 | Rapid urea test and/or biopsy | UBT | 47 ± 121 | 45 ± 131 | 441 | 421 | 201 | 191 | N = 64; E = 6; GU = 6; DU = 24 | N = 77; E = 8; GU = 0; DU = 15 |

| Zhang et al[37] | 95 | 7 | 49 | NA | NA | NA | NA | GU/DU = 24; G = 62; GA = 14 | ||||

| Jung et al[42] | 76 | 7 | Rapid urea test and/or UBT | Rapid urea test or UBT | 48 ± 12 | 50 ± 10 | 58 | 58 | NA | NA | GU = 39; DU = 32; GA = 10; G = 19 | GU = 38; DU = 33; GA = 18; G = 11 |

| Kuo et al[41] | 166 | 7 | Rapid urea test and/or biopsy or culture | Rapid urea test and/or biopsy or UBT | 50 ± 12 | 49 ± 14 | 53 | 48 | 14 | 12 | GU = 23; DU = 41; G = 36 | GU = 25; DU = 40; G = 35 |

Demographic data were reported together for both arms. In studies including patients after failure of more than one therapy, extrapolated data on patients pre-treated in second-line are reported in parenthesis; in those cases demographic data are referred to the entire study population. Pts: Patients (total number); L + A: Levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based therapy; Days of therapy (tp): Duration of L + A scheme; UBT: Urea breath test; Q: Quadruple standard therapy; UD: Ulcer-like dyspepsia; DD: Dysmotility-like dyspepsia; RD: Reflux-like dyspepsia; N: Normal; OE: Esophagitis; G: Gastritis; GU: Gastric ulcer; D: Duodenitis; O: Other; FD: Functional dyspepsia; DU: Duodenal ulcer; A: Adenoma; E: Erosion; GA: Gastric atrophy; F: Family history; NA: Not available.

Data on comparison of second-line levofloxacin-based triple regimens to bismuth-based QT after failure of one cycle of eradication therapy are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Levofloxacin-based second-line therapies vs quadruple bismuth-based regimens for Helicobacter pylori treatment

| Ref. | Ethnicity | Scheme |

Success |

Side effects |

Discontinuing therapy because of side effects |

||||||||

| Yes | Total | Completing | ITT % | PP % | Yes | Total | % | Yes | Total | % | |||

| Nista et al[21] | Caucasian | LAR (10 d; L: 500 mg OD) | 66 | 70 | 70 | 94.3 | 94.3 | 7 | 70 | 10.0 | 0 | 70 | 0.0 |

| Q07 | 44 | 70 | 64 | 62.9 | 68.8 | 15 | 70 | 21.4 | 5 | 70 | 7 | ||

| Perri et al[29] | Caucasian | LAP (7 d; L: 500 mg OD) | 37 | 58 | 56 | 63.8 | 66.1 | 3 | 58 | 5.2 | 1 | 58 | 1.7 |

| Q07 | 46 | 55 | 51 | 83.6 | 90.2 | 17 | 55 | 30.9 | 3 | 55 | 5.5 | ||

| Orsi et al1[38] | Caucasian | LAR (12 d; L: 500 mg OD) | 43 | 50 | 47 | 86.0 | 89 | 4 | 47 | 8.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Q07 | 44 | 50 | 44 | 88.0 | 91 | 11 | 44 | 25 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Bilardi et al[39] | Caucasian | LAP (10 d; L: 250 mg BD) | 16 | 23 | NA | 69.6 | NA | - | - | - | 1 | 44 | |

| Q07 | 6 | 17 | NA | 35.3 | NA | - | - | - | 1 | 46 | |||

| Nista et al1[35] | Caucasian | LAE (10 d; L: 500 mg OD) | 26 | 30 | 30 | 86.7 | 86.7 | - | - | - | |||

| Q07 | 25 | 35 | 31 | 71.4 | 80.6 | - | - | - | |||||

| Nista et al1[36] | Caucasian | LAR (10 d; L: 500 mg OD) | 42 | 46 | 46 | 91.3 | 91.3 | - | - | - | |||

| LAR (7 d; L: 500 mg OD) | 37 | 50 | 50 | 74.0 | 74.0 | - | - | - | |||||

| Q07 | 34 | 50 | 46 | 68 | 73.9 | - | - | - | |||||

| Gisbert et al[28] | Caucasian | LAO (7 or 10 d; L: 500 mg BD) | 83 | 112 | NA | 74 | NA | 39 | 112 | 34.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| Q07 | 21 | 38 | NA | 55 | NA | 6 | 38 | 15.8 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Wong et al1[44] | Asian | LALa (7 d; L: 500 mg BD) | 21 | 33 | NA | 63.6 | NA | - | - | - | |||

| Q07 | 22 | 30 | NA | 73.3 | NA | - | - | - | |||||

| Lee et al[80] | Asian | LAR (10 d; L: 200 mg BD) | 5 | 9 | 8 | 55.6 | 62.5 | - | - | - | |||

| Q07 | 4 | 14 | 10 | 28.6 | 40.0 | - | - | - | |||||

| Wong et al[19] | Asian | LALa (7 d; L: 500 mg BD) | 19 | 31 | NA | 61.3 | NA | 18 | 542 | 33.3 | NA | NA | NA |

| Q07 | 26 | 30 | NA | 86.7 | NA | 21 | 522 | 40.4 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Zhang et al[43] | Asian | LAE (7 d; L: 500 mg OD) | 42 | 49 | NA | 85.7 | NA | ||||||

| Q07 | 30 | 44 | NA | 68.2 | NA | ||||||||

| Zhang et al[37] | Asian | LAE (7 d; L: 500 mg OD) | 42 | 48 | 46 | 87.5 | 91.3 | 7 | 48 | ||||

| Q07 | 33 | 47 | 34 | 70.2 | 97.0 | 15 | 47 | ||||||

| Jung et al[42] | Asian | LAP (7 d; L: 300 mg BD) | 16 | 31 | 30 | 51.6 | 53.3 | 3 | 30 | 10.0 | 0 | 31 | 0.0 |

| Q07 | 22 | 45 | 35 | 48.9 | 62.9 | 11 | 35 | 31.4 | 1 | 45 | 2.2 | ||

| Kuo et al[41] | Asian | LAE (7 d; L: 500 mg OD) | 58 | 83 | 77 | 69.9 | 75.3 | 10 | 80 | 12.5 | 1 | 83 | |

| Q07 | 53 | 83 | 63 | 63.9 | 84.1 | 25 | 71 | 35.2 | 5 | 83 | |||

1Data arisen from abstract publication;

side effects calculated on the entire study population (not stratified for number of failed previous therapy). L: Levofloxacin; OD: Once daily; BD: Twice daily; LA/La: Levofloxacin/Lansoprazole; ITT: Intention-to-treat eradication rates; PP: Per-protocol; NA: Not available; LAR: Levofloxacin/amoxicillin/rabeprazole; LAO: Levofloxacin/amoxicillin/omeprazole; LAE: Levofloxacin/amoxicillin/esomeprazole; LAP: Levofloxacin/amoxicillin/pantoprazole.

In our analysis, we extrapolated exclusively the data matching our strict inclusion criteria. We also re-calculated all the eradication percentages from the included studies. In all cases, the results matched the reported data, except one.

In an Italian population study, 10-d levofloxacin-based triple scheme in association with either amoxicillin or tinidazole, was superior to both 7-d and 14-d QT. Specifically, triple therapy eradication rates were 94% with amoxicillin vs 63% and 68% at 7 d and 14 d, respectively for QT. A high incidence of adverse events (33%) was observed in the 14-d QT group, although the same scheme administered for 7 d was well tolerated. Dropouts and severe adverse events were observed exclusively in the quadruple regimen[21]. The same authors compared two 10-d levofloxacin-based (500 mg OD) triple schemes in combination with either amoxicillin or azithromycin with the standard QT regimen. Eradication rates of levofloxacin-based groups were higher, even if not significantly, compared with standard QT (86.6% and 71.4%, respectively), but incidence of side effects was significantly lower (26.6% vs 60%). Dropouts occurred only in the QT group[35,36].

In terms of duration of treatment, the same researchers compared efficacy and tolerability of 7 d and 10 d levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based treatment to 7 d QT, demonstrating a higher cure rate for the triple 10-d levofloxacin regimen (91.3%) compared to both the 7-d levofloxacin-based or QT regimen (74% and 68%, respectively), with optimal tolerability[35,36]. Zhang et al[37] also confirmed similar results.

Orsi et al[38] have studied efficacy of a 12-d treatment course by comparing the levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based regimen with QT. Both regimens were equally effective (86% vs 88%) but the triple regimen was better tolerated (incidence of side effects: 8.6% vs 24%).

A drastic difference in eradication rates were observed in another Italian study in which the levofloxacin-based triple and quadruple regimens achieved an eradication rate of 70% vs 35%, respectively, in second-line, even if patients were given a full-dose course of PPI for 1 wk prior to bismuth therapy. Interestingly, levofloxacin-based triple regimen was successful in most patients with both metronidazole- and clarithromycin-resistant strains, whereas QT was less effective, particularly when metronidazole resistance occurred[39].

Bilardi et al[39] used LA-based triple therapy both in first- and second-line compared to standard first-line triple and quadruple second-line regimens, respectively. In first-line, eradication rate of levofloxacin-based and standard triple regimen was 69.8% and 74%, respectively, while as rescue regimen, levofloxacin-based therapy achieved an eradication rate of 62.5% compared to 40% for the standard QT regimen.

Gisbert et al[40] compared 7-d levofloxacin-based therapy with a quadruple ranitidine bismuth citrate-based regimen and reported an identical eradication rate of 68% for both regimens, with similar incidence of side effects (38% vs 36%, respectively). Nevertheless, the antisecretory activity of ranitidine might have contributed to the eradication rate in the QT regimen. Conversely, dose of levofloxacin (500 mg BD) and duration (7 d) of treatment might have affected efficacy (shorter treatment) and tolerance (high dosage) in the triple regimen[40].

In the study by Kuo et al[41], levofloxacin triple regimen and QT eradication rates were 69.9% vs 63.9%, respectively, and although compliance was similar, incidence of side effects was 12.6% in the LA vs 35.2% in the QT groups. In this study, levofloxacin resistance was analyzed and was a crucial predictor for eradication failure (21.2% of patients).

In a Korean trial, 7 d levofloxacin-based therapy and standard QT achieved comparable but low cure rates (51.6% vs 48.9%), even if the triple regimen was better tolerated (adverse events incidence: 10% vs 31.4%)[42]. Another Asian trial confirmed the high cure rate of levofloxacin-based therapy for 7 d (85.7%)[43].

Finally, few studies have demonstrated superiority of the recommended QT regimen compared with the levofloxacin triple regimen. QT was superior to levofloxacin-based regimen for persistent H. pylori infection in the study conducted by Perri et al[29] (eradication rate: 63% in the levofloxacin group). In this trial bismuth- and ranitidine/bismuth citrate-based QT regimens achieved a cure rate of 83% and 85%, respectively, although a higher incidence of side effects was observed in the bismuth-treated group (30.9% vs 5.1%). Conversely, adverse events occurred in 3.3% of patients treated with levofloxacin.

Wong et al[44] reported an eradication rate of 73% and 64% in second-line for QT and levofloxacin-based regimens, respectively. Similarly, in a study conducted in Hong Kong, second-line 7-d triple levofloxacin-based therapy achieved an eradication rate of 61% vs 87% with QT, due to resistance to levofloxacin (18% of patients)[19]. However, the study included a small sample of refractory patients and eradication rate was superior in subjects in the LA group with dual resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin respect to antibiotics resistant patients in Q group (79% vs 65%, respectively). However, treatment choice was based on antibiotic susceptibility testing and might not reflect common clinical practice[19].

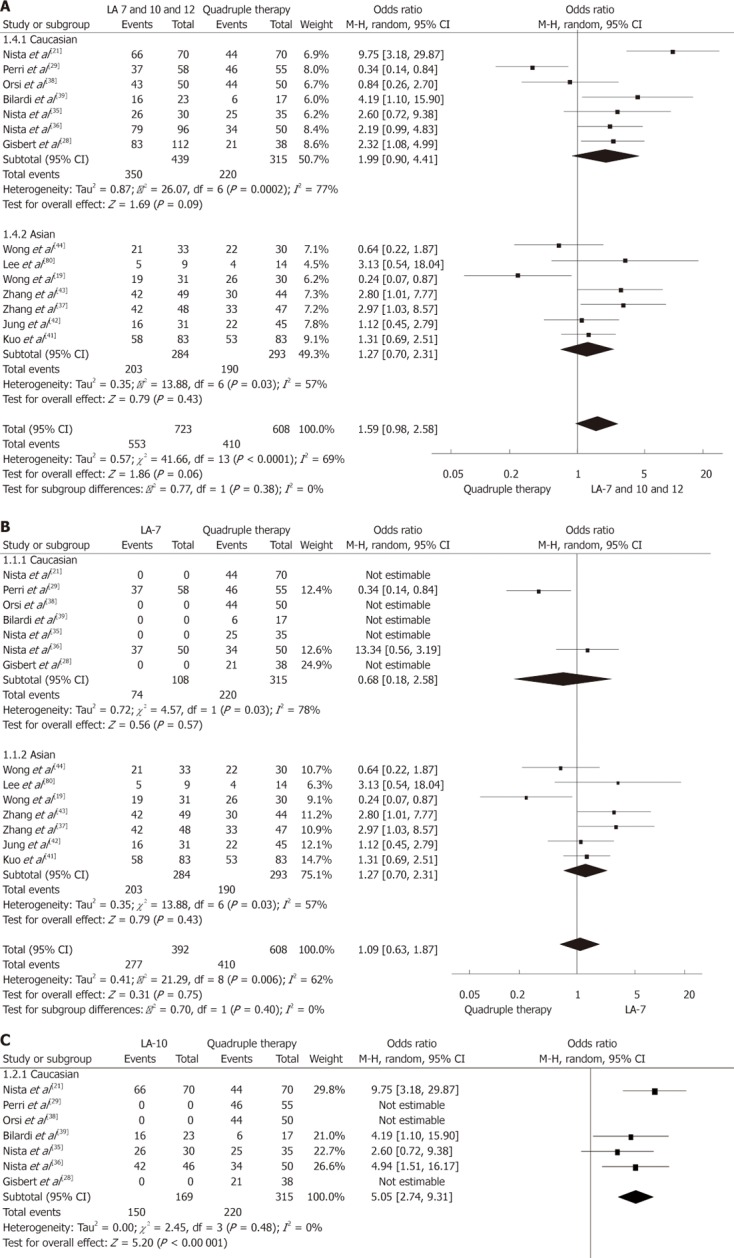

Results of our meta-analysis are summarized in Figure 1. Overall eradication rate (pooled data) with levofloxacin was 76.5% (95% CI: 54.4%-97.6%). When exclusively 7-d regimens were included, cure rate was 70.6% (95% CI: 40.2%-99.1%), whereas for the 10-d regimen, eradication rate was significantly higher (88.7%; 95% CI: 56.1%-109.9%; P < 0.05). Mean eradication rate for QT was 67.4% (95% CI: 42.4%-91.6%).

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis comparing the efficacy of anti-Helicobacter pylori levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based triple therapy vs quadruple therapy 7-10 or 12 d (A), 7 d (B), 10 d (C) levofloxacin/amoxicillin regimens were considered. CI: Confidence interval; LA: Levofloxacin/amoxicillin.

The meta-analysis showed a trend indicating superiority of any LA regimens (7, 10 or 12 d) to QT (OR: 1.59; 95% CI: 0.98-2.58; P = 0.06; Figure 1A). Both 7-d LA and QT regimens showed comparable efficacy (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.63-1.87; P = 0.40; Figure 1B), whereas the 10-d LA regimen was significantly more effective (OR: 5.05; 95% CI: 2.74-9.31; P < 0.00 001; Figure 1C).

No differences were reported in QT eradication rates between Asian and European studies, whereas LA regimens were more effective in Caucasians (78.3% vs 67.7%; P = 0.05). Of note, if data on comparison between LA and QT regimens were stratified by ethnicity (Figure 1A), any levofloxacin regimen was more effective in the Caucasian population (P = 0.09). Those findings were not confirmed when only 7-d levofloxacin regimens were included (Figure 1B). No data were available on 10-d levofloxacin regimens in Asian populations (Figure 1C).

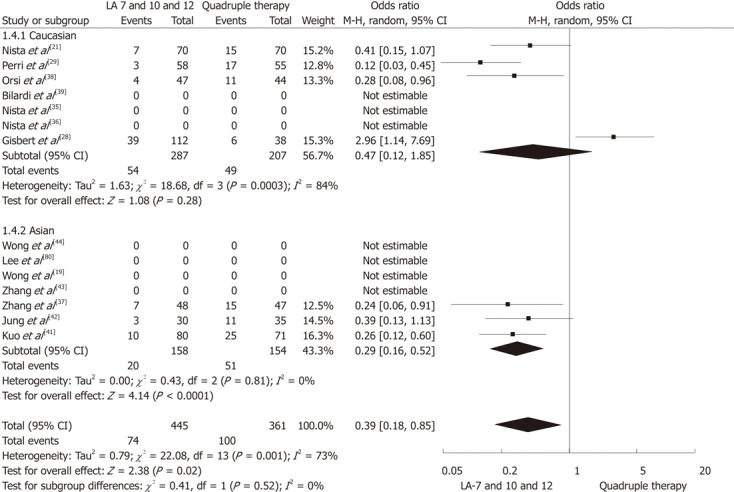

Mean incidence of side effects (pooled data) was lower in LA regimens (13.7%, 95% CI: 12%-24%) compared with standard QT (27.2%, 95% CI: 24%-34%). The OR for this comparison was 0.39 (95% CI: 0.18-0.85; P = 0.02) at meta-analysis (Figure 2). When incidence of side effects (pooled data) was stratified by ethnicity, no differences were registered between the two geographical areas for the levofloxacin regimens (14.8% vs 12.1%, respectively in Europe and Asia), whereas a slightly higher rate was reported in the Asian population treated with QT (32.5% vs 23.3%, P = 0.09). Moreover, the lower risk of occurrence of side effects in the levofloxacin arms overall was mainly due to the Asian studies contribution.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis comparing the incidence of side effects with levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based triple therapy vs quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. CI: Confidence interval; LA: Levofloxacin/amoxicillin.

DISCUSSION

Antibiotic resistance is the main cause of failure in curing H. pylori infection[45-49]. Other factors determining eradication rate are: H. pylori strain, patient compliance, and properties of drugs administered[2].

Levofloxacin, a second-generation fluoroquinolone, with a broad spectrum of activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria[50-52], is a recognized antimicrobial alternative to the standard antibiotics used to treat H. pylori infection. Levofloxacin is mainly indicated to treat infections of respiratory and genitourinary tract, skin and skin structures[33,51,53-55]. In recent years, its role has been successfully extended to treatment of H. pylori infection and has been included as treatment of choice in guidelines[15,33,56]. Its optimal tolerance spectrum, with the most frequent adverse events being nausea and diarrhea, makes it a safe alternative[57]. Only a few cases of QTc prolongation, seizures, glucose disturbances and tendonitis have been reported[33,51,56]. Although primary resistance is infrequent, resistance to quinolones is easily acquired in areas of high consumption[58]. In Asian countries, levofloxacin resistance has recently increased[59,60]. In particular, in Hong Kong, Korea and Japan, estimated H. pylori resistance rates for levofloxacin are 11.5%, 21.5% and 15% respectively[61,62]. In the Chinese adolescent population, all H. pylori strains were found to be resistant to levofloxacin[63,64]. In Europe, such as Spain, France, Netherlands, Austria and Portugal, fluoroquinolone resistance is less than 10%[65-69]. However, despite a reported levofloxacin resistance rate of 18%, Italian guidelines recommend levofloxacin regimens for second-line therapy, with optimal results[16]. Moreover, antibiotic resistance testing is not routinely performed to guide prescription. Therefore, even if widely used, published data on levofloxacin-based regimens for H. pylori eradication are extremely heterogeneous. Differences in dosages, length of treatment, drug combination, patients’ demographic characteristics, and previous courses of therapy, preclude a definitive conclusion.

The present study included only studies comparing cure rate and tolerability of standard QT regimen to 7 or 10 d combination of LA-based triple therapy in second-line, to provide guidance in clinical practice. In accordance with previous reports[70-72], our data showed that 7 d LA-based triple regimen and QT achieved similar efficacy results, whereas LA-based regimen administered for 10 d was more effective than QT. Thus, tolerability was optimal in LA-based triple therapy and patients experienced a lower rate of adverse events compared to patients treated with standard QT, with the exception of a single discordant study[28]. However, in a multicenter study, the same author reported remarkably superior tolerability using a 10-d levofloxacin-based regimen[38,40].

In previous studies, dose of quinolone appeared the crucial factor influencing the incidence of side effects[70,71,73]. In most studies included in the analysis, levofloxacin has been administered at a dosage of 500 mg daily. Interestingly, a higher incidence of side effects was registered in one of the trials using 1 g in two divided doses[28].

Statistical comparison of side effects experienced in 7-d vs 10-d groups was not consistent due to the structure of the selected studies. With the exception of the study by Gisbert et al[28], tolerability was excellent in all other trials using levofloxacin-based regimens for 10 d or longer. Probably, acceptance of LA therapy depends on the simplicity of the therapeutic regimen itself. Although a new preparation of single three-in-one capsules containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline has been recently proposed in first-line[74], QT still consists of a complex scheme (12 pills/d), and bismuth salts are no longer available in many countries. On the contrary, levofloxacin-based therapy appears simple (5 pills/d), effective (10-d regimen eradication rate: 88.7%) and safe (overall side effects incidence: 13.7%). Duration of treatment appeared the unique factor influencing the efficacy[75].

Nevertheless, considering that the ideal for H. pylori infection might differ between areas, countries and races[76-78], we performed an additional analysis on efficacy in different parts of the world.

In a sub-analysis comparing Asian and European trials, QT was equally effective, while LA-based regimens were more effective in the European population. Differences in efficacy rates between Asian and European populations using LA-based schemes might be explained with primary antibiotic resistance and/or genetic background. The meta-analysis showed that the LA-based regimen was more effective in Caucasians only when any regimen was included. However, 10-d levofloxacin-based treatment has never been tested in Asian countries and efficacy increases with duration of treatment, therefore, it is difficult to establish whether differences reported depended on ethnicity or duration of therapy.

Regarding incidence of side effects, ethnicity appeared to affect tolerability of QT compared with LA-based therapy in Asian populations. However, the single outlier among European trials might bias this finding.

Apart from levofloxacin, other regimens containing fluoroquinolones have been proposed both in first- and second-line H. pylori treatment. Among these, moxifloxacin-based regimens appear interesting (eradication rate up to 90% and 70%, respectively in first and second-line[72,75,79]. With respect to levofloxacin, moxifloxacin has been relatively more recently introduced on the market, with a consequent possibly lower rate of antibiotic resistance. However, it is more expensive. Nevertheless, no conclusive recommendations can be issued on which fluoroquinolone should be used because there are no trials comparing the two drugs.

Our results are in accordance with previous meta-analyses assessing efficacy and safety of second-generation fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin and moxifloxacin[13,71,72,79], for H. pylori eradication. However, compared to previous studies, our study included the most up to date collection of RCTs and most importantly, compared exclusively second-line treatments and analyzed geographical stratification.

Our meta-analysis had several limitations, mainly due to heterogeneity among trials (different dosing schedules and duration of treatment). Sub-analyses were mainly affected by the small sample size for each category. Finally, the lack of data available on use of 10 d LA-based therapy in Asian populations did not allow a definitive conclusion about the influence of ethnicity on treatment success. Moreover, considering the suboptimal tolerance of QT in Asian populations, alternative strategies, such as 10 d LA-based therapy, and randomized trials in this geographic setting would be desirable.

In our analysis, we selected exclusively RCTs comparing LA-based triple regimens to standard QT to provide practical useful data on a specific treatment to use as rescue regimen of choice due to the rare H. pylori resistance to amoxicillin.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis strongly supports the use of 10 d LA-based triple regimen as a simple (5 pills/d) second-line treatment for H. pylori eradication, with an excellent eradication rate and tolerability profile in comparison to standard recommended QT in Asian and European countries. Nevertheless, quinolone resistance monitoring in different geographical areas is required.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Dr. Shahab Abid, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Aga Khan University, Stadium Road, PO Box 3500, Karachi 74800, Pakistan; Siegfried Wagner, Professor, Medizinische Klinik II, Klinikum Deggendorf, Perlasberger Str. 41, 94469 Deggendorf, Germany

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snaith A, El-Omar EM. Helicobacter pylori: host genetics and disease outcomes. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;2:577–585. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vakil N, Megraud F. Eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:985–1001. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sachs G, Scott DR. Helicobacter pylori: Eradication or Preservation. F1000 Med Rep. 2012;4:7. doi: 10.3410/M4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alakkari A, Zullo A, O’Connor HJ. Helicobacter pylori and nonmalignant diseases. Helicobacter. 2011;16 Suppl 1:33–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zullo A, Perna F, Hassan C, Ricci C, Saracino I, Morini S, Vaira D. Primary antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated in northern and central Italy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1429–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mégraud F. Detection of Helicobacter pylori and its sensitivity to antibiotics. A step forward in the use of molecular methods. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2007;31:790–791. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(07)73965-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egan BJ, Katicic M, O’Connor HJ, O’Morain CA. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2007;12 Suppl 1:31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Megraud F. Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2007;56:1502. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.132514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolle K, Malfertheiner P. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1863–1873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gisbert JP. “Rescue” regimens after Helicobacter pylori treatment failure. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5385–5402. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham DY. Efficient identification and evaluation of effective Helicobacter pylori therapies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gisbert JP, Bermejo F, Castro-Fernández M, Pérez-Aisa A, Fernández-Bermejo M, Tomas A, Barrio J, Bory F, Almela P, Sánchez-Pobre P, et al. Second-line rescue therapy with levofloxacin after H. pylori treatment failure: a Spanish multicenter study of 300 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:71–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caselli M, Zullo A, Maconi G, Parente F, Alvisi V, Casetti T, Sorrentino D, Gasbarrini G. “Cervia II Working Group Report 2006”: guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Italy. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malfertheiner P, Mégraud F, O’Morain C, Hungin AP, Jones R, Axon A, Graham DY, Tytgat G. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht 2-2000 Consensus Report. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:167–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klotz U. Pharmacokinetic considerations in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;38:243–270. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200038030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong WM, Gu Q, Chu KM, Yee YK, Fung FM, Tong TS, Chan AO, Lai KC, Chan CK, Wong BC. Lansoprazole, levofloxacin and amoxicillin triple therapy vs. quadruple therapy as second-line treatment of resistant Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:421–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perna F, Zullo A, Ricci C, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. Levofloxacin-based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori re-treatment: role of bacterial resistance. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:1001–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nista EC, Candelli M, Cremonini F, Cazzato IA, Di Caro S, Gabrielli M, Santarelli L, Zocco MA, Ojetti V, Carloni E, et al. Levofloxacin-based triple therapy vs. quadruple therapy in second-line Helicobacter pylori treatment: a randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:627–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischbach LA, van Zanten S, Dickason J. Meta-analysis: the efficacy, adverse events, and adherence related to first-line anti-Helicobacter pylori quadruple therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1071–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasbarrini A, Lauritano EC, Nista EC, Candelli M, Gabrielli M, Santoro M, Zocco MA, Cazzato A, Finizio R, Ojetti V, et al. Rifaximin-based regimens for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a pilot study. Dig Dis. 2006;24:195–200. doi: 10.1159/000090330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guslandi M. Review article: alternative antibacterial agents for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1543–1547. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cammarota G, Cianci R, Cannizzaro O, Martino A, Fedeli P, Lecca PG, di Caro S, Cesaro P, Branca G, Gasbarrini G. High-dose vs low-dose clarithromycin in 1-week triple therapy, including rabeprazole and levofloxacin, for Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:110–114. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200402000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Francesco V, Ierardi E, Hassan C, Zullo A. Furazolidone therapy for Helicobacter pylori: is it effective and safe? World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1914–1915. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fung HB, Doan TL. Tinidazole: a nitroimidazole antiprotozoal agent. Clin Ther. 2005;27:1859–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gisbert JP, Gisbert JL, Marcos S, Jimenez-Alonso I, Moreno-Otero R, Pajares JM. Empirical rescue therapy after Helicobacter pylori treatment failure: a 10-year single-centre study of 500 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:346–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perri F, Festa V, Merla A, Barberani F, Pilotto A, Andriulli A. Randomized study of different ‘second-line’ therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection after failure of the standard ‘Maastricht triple therapy’. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:815–820. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osato MS, Reddy SG, Piergies AA, Bochenek WJ, Testa RT, Graham DY. Comparative efficacy of new investigational agents against Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:487–492. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vítor JM, Vale FF. Alternative therapies for Helicobacter pylori: probiotics and phytomedicine. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;63:153–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson VR, Perry CM. Levofloxacin : a review of its use as a high-dose, short-course treatment for bacterial infection. Drugs. 2008;68:535–565. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wimer SM, Schoonover L, Garrison MW. Levofloxacin: a therapeutic review. Clin Ther. 1998;20:1049–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JM, Kim JS, Kim N, Jung HC, Song IS. Distribution of fluoroquinolone MICs in Helicobacter pylori strains from Korean patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:965–967. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nista EC, Candelli M, Fini L, Cazzato IA, Finizio R, Laurkano C, Cammarota C, Martino A, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. 10 days levofloxacin based triple therapy in second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(4 Suppl 2):A–74. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nista EC, Candelli M, Santoro M, Cazzato IA, Finizio R, Fini L, Ojetti V, Zocco MA, Gabrielli M, Santarelli L, et al. Levofloxacin base triple therapy in second-line treatment for H. pylori eradication: Update. Gastroeneterology. 2005;128:A–63. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Wu J, Jia YG. Rescue regimen after Helicobacter pylori eradication failure with triple therapy. Chin J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;24:361–363. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orsi P, Pinazzi O, Aragona G, Di Mario F. Rabeprazole/levofloxacin based triple therapy as a salvatage treatment after failure of H. pylori eradication with standard regimens. Helicobacter. 2003;8:339–493. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bilardi C, Dulbecco P, Zentilin P, Reglioni S, Iiritano E, Parodi A, Accornero L, Savarino E, Mansi C, Mamone M, et al. A 10-day levofloxacin-based therapy in patients with resistant Helicobacter pylori infection: a controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gisbert JP, Gisbert JL, Marcos S, Moreno-Otero R, Pajares JM. Levofloxacin- vs. ranitidine bismuth citrate-containing therapy after H. pylori treatment failure. Helicobacter. 2007;12:68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo CH, Hu HM, Kuo FC, Hsu PI, Chen A, Yu FJ, Tsai PY, Wu IC, Wang SW, Li CJ, et al. Efficacy of levofloxacin-based rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection after standard triple therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:1017–1024. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung HS, Shim KN, Baik SJ, Na YJ, Kang MJ, Jung JM, Ha CY, Jung SA, Yoo K. [Efficacy of levofloxacin-based triple therapy as second-line Helicobacter pylori eradication] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;51:285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Wu J, Jia YG. Observation on effect of levofloxacin-based therapy as a salvage therapy to Helicobacter pylori. Chin J Dig. 2007;19:320–321. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong WM, Wong WM, Chu KM, Yee YK. Randomized controlled trial of lansoprazole, levofloxacin and amoxycillin tryple therapy vs lansoprazole-based quadruple therapy as a rescue treatment after failure of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication with standard triple therapies. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl VI):A–124. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selgrad M, Malfertheiner P. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:565–570. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32834bb818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selgrad M, Bornschein J, Malfertheiner P. Guidelines for treatment of Helicobacter pylori in the East and West. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9:581–588. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chuah SK, Tsay FW, Hsu PI, Wu DC. A new look at anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3971–3975. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i35.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Francesco V, Giorgio F, Hassan C, Manes G, Vannella L, Panella C, Ierardi E, Zullo A. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:409–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNulty CA, Lasseter G, Shaw I, Nichols T, D’Arcy S, Lawson AJ, Glocker E. Is Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance surveillance needed and how can it be delivered? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1221–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McNulty CA Levofloxacin. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2008;88:119–121. doi: 10.1016/S1472-9792(08)70013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Croom KF, Goa KL. Levofloxacin: a review of its use in the treatment of bacterial infections in the United States. Drugs. 2003;63:2769–2802. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363240-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Connor A, Gisbert JP, McNamara D, O’Morain C. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection 2011. Helicobacter. 2011;16 Suppl 1:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Albertson TE, Dean NC, El Solh AA, Gotfried MH, Kaplan C, Niederman MS. Fluoroquinolones in the management of community-acquired pneumonia. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:378–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schiller DS, Parikh A. Identification, pharmacologic considerations, and management of prostatitis. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu HH. Safety profile of the fluoroquinolones: focus on levofloxacin. Drug Saf. 2010;33:353–369. doi: 10.2165/11536360-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Di Caro S, Zocco MA, Cremonini F, Candelli M, Nista EC, Bartolozzi F, Armuzzi A, Cammarota G, Santarelli L, Gasbarrini A. Levofloxacin based regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1309–1312. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sprandel KA, Rodvold KA. Safety and tolerability of fluoroquinolones. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;Suppl 3:S29–S36. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(03)90027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carothers JJ, Bruce MG, Hennessy TW, Bensler M, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, Hurlburt DA, Parkinson AJ, Coleman JM, McMahon BJ. The relationship between previous fluoroquinolone use and levofloxacin resistance in Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e5–e8. doi: 10.1086/510074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katelaris PH. Helicobacter pylori: antibiotic resistance and treatment options. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1155–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, Ang TL, Hunt R, Talley NJ, Lam SK, Xiao SD, Tan HJ, Wu CY, et al. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1587–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyachi H, Miki I, Aoyama N, Shirasaka D, Matsumoto Y, Toyoda M, Mitani T, Morita Y, Tamura T, Kinoshita S, et al. Primary levofloxacin resistance and gyrA/B mutations among Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Helicobacter. 2006;11:243–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee CC, Lee VW, Chan FK, Ling TK. Levofloxacin-resistant Helicobacter pylori in Hong Kong. Chemotherapy. 2008;54:50–53. doi: 10.1159/000112416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang LP, Zhuang ML, Gu CP. [Antimicrobial resistance of 36 strains of Helicobacter pylori in adolescents] Zhongguo Dangdai Erke Zazhi. 2009;11:210–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu G, Xu X, He L, Ding Z, Gu Y, Zhang J, Zhou L. Primary antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori isolated from Beijing children. Helicobacter. 2011;16:356–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cabrita J, Oleastro M, Matos R, Manhente A, Cabral J, Barros R, Lopes AI, Ramalho P, Neves BC, Guerreiro AS. Features and trends in Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance in Lisbon area, Portugal (1990-1999) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:1029–1031. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fujimura S, Kato S, Iinuma K, Watanabe A. In vitro activity of fluoroquinolone and the gyrA gene mutation in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from children. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:1019–1022. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heep M, Kist M, Strobel S, Beck D, Lehn N. Secondary resistance among 554 isolates of Helicobacter pylori after failure of therapy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:538–541. doi: 10.1007/s100960000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cuadrado-Lavín A, Salcines-Caviedes JR, Carrascosa MF, Mellado P, Monteagudo I, Llorca J, Cobo M, Campos MR, Ayestarán B, Fernández-Pousa A, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to six antibiotics currently used in Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:170–173. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vécsei A, Kipet A, Innerhofer A, Graf U, Binder C, Gizci H, Hammer K, Bruckdorfer A, Huber WD, Hirschl AM, et al. Time trends of Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in children living in Vienna, Austria. Helicobacter. 2010;15:214–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gisbert JP, Morena F. Systematic review and meta-analysis: levofloxacin-based rescue regimens after Helicobacter pylori treatment failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saad RJ, Schoenfeld P, Kim HM, Chey WD. Levofloxacin-based triple therapy vs bismuth-based quadruple therapy for persistent Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Y, Huang X, Yao L, Shi R, Zhang G. Advantages of Moxifloxacin and Levofloxacin-based triple therapy for second-line treatments of persistent Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta analysis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2010;122:413–422. doi: 10.1007/s00508-010-1404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tursi A, Elisei W, Giorgetti G, Picchio M, Brandimarte G. Efficacy, tolerability, and factors affecting the efficacy of the sequential therapy in curing Helicobacter pylori infection in clinical setting. J Investig Med. 2011;59:917–920. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0b013e318217605f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Malfertheiner P, Bazzoli F, Delchier JC, Celiñski K, Giguère M, Rivière M, Mégraud F. Helicobacter pylori eradication with a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole vs clarithromycin-based triple therapy: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:905–913. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Di Caro S, Franceschi F, Mariani A, Thompson F, Raimondo D, Masci E, Testoni A, La Rocca E, Gasbarrini A. Second-line levofloxacin-based triple schemes for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bruce MG, Maaroos HI. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2008;13 Suppl 1:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goh KL, Chan WK, Shiota S, Yamaoka Y. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and public health implications. Helicobacter. 2011;16 Suppl 1:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hori K, Miwa H, Matsumoto T. Efficacy of 2-week, second-line Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy using rabeprazole, amoxicillin, and metronidazole for the Japanese population. Helicobacter. 2011;16:234–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cheng HC, Chang WL, Chen WY, Yang HB, Wu JJ, Sheu BS. Levofloxacin-containing triple therapy to eradicate the persistent H. pylori after a failed conventional triple therapy. Helicobacter. 2007;12:359–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee JH, Hong SP, Kwon CI, Phyun LH, Lee BS, Song HU, Ko KH, Hwang SG, Park PW, Rim KS, et al. [The efficacy of levofloxacin based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;48:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]