Abstract

The exact aetiology of sigmoid volvulus in Parkinson's disease (PD) remains unclear. A multiplicity of factors may give rise to decreased gastrointestinal function in PD patients. Early recognition and treatment of constipation in PD patients may alter complications like sigmoid volvulus. Treatment of sigmoid volvulus in PD patients does not differ from other patients and involves endoscopic detorsion. If feasible, secondary sigmoidal resection should be performed. However, if the expected surgical morbidity and mortality is unacceptably high or if the patient refuses surgery, percutaneous endoscopic colostomy (PEC) should be considered. We describe an elderly PD patient who presented with sigmoid volvulus. She was treated conservatively with endoscopic detorsion. Surgery was consistently refused by the patient. After recurrence of the sigmoid volvulus a PEC was placed.

Keywords: Colonic dysfunction, Colostomy, Endoscopic treatment, Parkinson’s disease, Sigmoid volvulus

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common in Parkinson's disease (PD) and may give rise to life threatening conditions such as sigmoid volvulus. Early recognition and treatment of constipation in PD patients may alter complications such as sigmoid volvulus. We describe a patient known to have PD with recurrent bowel dilatation associated with sigmoid volvulus. Furthermore, we review the relevant literature concerning volvulus in patients with PD and treatment of this condition.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old female patient was admitted three times within three months to the gastrointestinal ward with recurrent painless abdominal distension. A week before her first admission she noticed progressive abdominal distension. Apart from nausea she experienced no other symptoms.

Her past medical history revealed breast carcinoma for which she had undergone a modified radical mastectomy in 1997 and resection of local recurrence combined with hormonal therapy in 2005. She was also known to have severe PD for more then twenty years. Medication consisted of levodopa/carbidopa and amantadine.

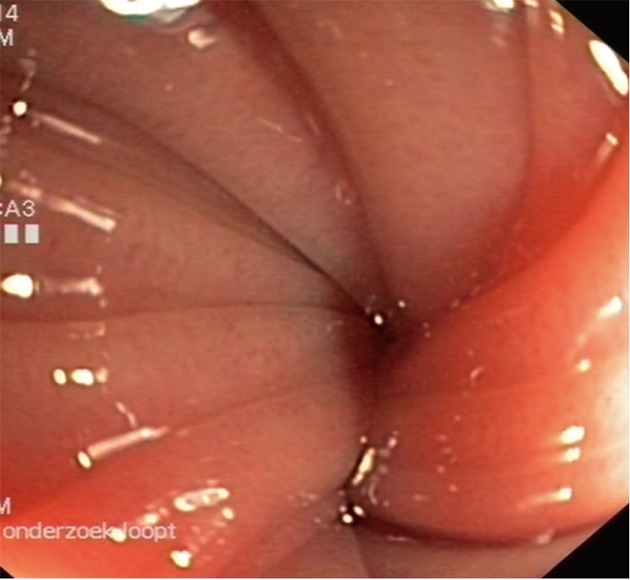

On physical examination at admission the patient was not very ill and had normal vital parameters. Her abdomen was grossly distended and high pitched bowel sounds were heard. The clinical diagnosis of an ileus was made. Laboratory tests were unremarkable without any sign of inflammation. An abdominal X-ray revealed a typical coffee bean-shaped sigmoid with gross dilatation up to 11 cm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Typical "bean-shaped" sigmoid with distension up to 11 cm representing sigmoid volvulus.

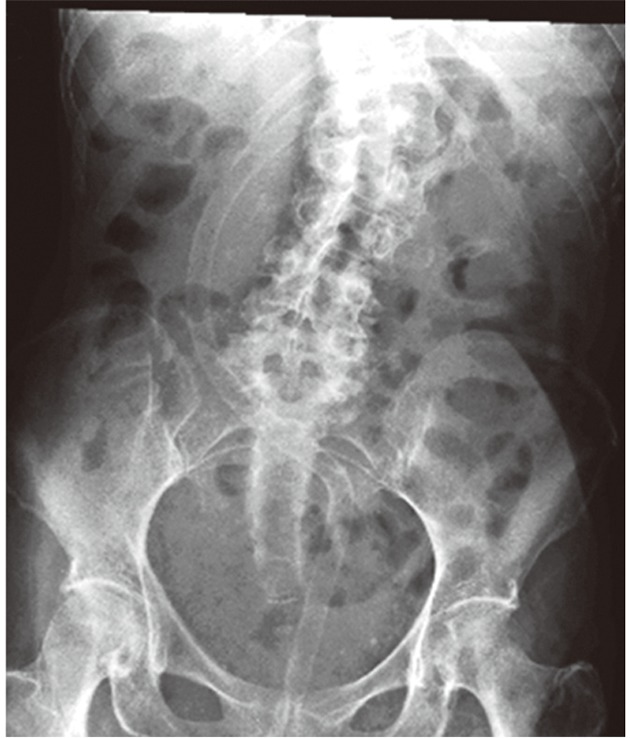

The patient was treated with enemas and laxatives. A colonoscopy was performed which did not reveal any mucosal irregularities. At 40 cm from the anus a strangulation of the sigmoid was seen with proximal dilatation of the colon which is pathognomonic for volvulus (Figure 2). Surgical treatment was repeatedly considered but consistently refused by the patient. Decompression of the colon was finally established by a large (11 French) cannula inserted proximal from the evident torsion of the sigmoid (Figure 3). Ten days after admission the patient was discharged in good clinical condition.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic image of torsion of sigmoid: "Toffee-sign".

Figure 3.

Colonic dilatation resolved after endoscopic detorsion with large bore rectal tube placement.

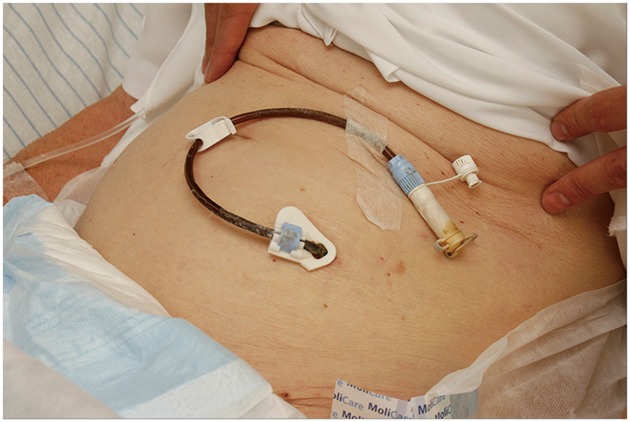

However, two months later she was readmitted with a recurrence of sigmoid volvulus. For the second time, conservative treatment with endoscopic derotation of the affected sigmoid and placement of a cannula for decompression was performed. To prevent further recurrence, a percutaneous endoscopic colostomy (PEC) was placed in the distal colon to achieve fixation to the abdominal wall (Figure 4). No complications occurred. The patient was discharged a few days later. Two years later she was admitted with a third recurrence of sigmoid volvulus and was again successfully treated with endoscopic derotation. The patient still persists in her wish not to be operated on.

Figure 4.

Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy has been placed.

DISCUSSION

Colonic dysfunction in PD

Parkinsonism is an extrapyramidal syndrome with symptoms consisting of a variable combination of general rigidity, disturbance of posture, gait and tremor. The signs of this chronic and progressive disease, affecting mostly people of sixty-five years and older, are caused by loss of nerve cells in the pigmented substantia nigra pars compacta and the locus coeruleus in the midbrain. Apart from typical parkinsonian features as mentioned above, gastrointestinal symptoms are common, especially motility disorders, varying from swallowing disorders, gastroparesis to bowel dysmotility and anorectal dysfunction[1-3]. Constipation is one of the most common gastrointestinal features in PD patients. Constipation may even precede typical symptoms 10 or 20 years before the onset of PD[4-7]. Several reports have revealed that constipation occurs in up to 50% of patients with PD. The severity of constipation seems be directly related to the severity and duration of PD[1].

There is a multiplicity of factors contributing to constipation in PD patients. Reduced physical activity and a decrease in swallowing saliva may play a role in constipation. Antiparkinsonian drugs are thought to contribute to diminished bowel motions[8], although an association between constipation and PD was noted even before the introduction of antiparkinsonian drugs by Parkinson in 1817. Several studies did not confirm the correlation between medication and delayed colonic transit time[1,9]. In PD, colonic transit time is prolonged in all segments of the colon[8-11]. Defecation itself can be impaired by decreased phasic rectal contractions, weak abdominal strain and/or paradoxical sphincteric contractions during defecation[10]. However, the exact pathophysiology of autonomic gut dysfunction remains obscure.

Constipation may result from both peripheral as well as central nerves. Depletion of dopamine-containing neurons in the central nervous system is a basic defect in PD. On the other hand, a substantial decrease in dopaminergic myenteric neurons has been documented[12]. Deposition of intracytoplasmic hyaline inclusions, so-called Lewy bodies, can be found not only centrally in the pigmented nuclei but also in the myenteric and submucosal plexus[13]. Conditions associated with constipation in PD patients include megacolon and sigmoid volvulus[14,15].

Volvulus and PD

In sigmoid volvulus there is twisting of the sigmoid around its mesenteric axis. Apart from obstruction it may also involve strangulation of the main vessels at the base of the affected mesentery. Sigmoid volvulus is the third leading cause of large bowel obstruction in adults and is even more common in the elderly[16-18]. It can be a life threatening condition with high mortality rates of up to 50%[19].

The incidence of sigmoid volvulus in PD is not known. Only a few reports have been published concerning this association[14,20-22]. A longstanding history of constipation is, amongst anatomic variations and neuropsychiatric diseases, one of the risk factors for the development of volvulus because of an abnormally loaded loop of bowel[23,24]. The diagnosis of volvulus is based on physical examination in combination with an abdominal X-ray revealing a typical "coffee bean" shaped sigmoid. In the majority of cases no further investigation is required to confirm the diagnosis of volvulus[25]. If there is any doubt about possible obstructive disease, an abdominal computed tomography-scan can be considered. However, colonoscopy is the most favourable diagnostic tool to visualize obstructive colonic moments. The endoscopic picture of volvulus shows a pinpoint lumen with wrenched sides. When passing the pinpoint opening one sees a grossly dilated lumen (Figure 2). In the case of volvulus, endoscopy allows immediate treatment.

Management of sigmoid volvulus

Awareness of the high incidence of gastrointestinal disorders, and especially constipation, in PD patients is mandatory in order to recognise a condition such as sigmoid volvulus. The question remains as to whether the aetiology of sigmoid volvulus in this specific group of patients is different. If constipation is the main cause, the primary focus should be on medical prophylactic treatment with laxatives. However, if patients with PD have redundant sigmoid, surgery remains the first choice of treatment. No data have been published related to this question. Even for volvulus in general, the published data are too scarce to allow high level evidence-based judgement.

Early aggressive treatment of constipation with dietary adjustments, physiotherapy, bulk-forming agents and laxatives should be the aim in all PD patients. The prokinetic agent, cisapride, has been shown to reduce colonic transit time in PD patients, but seemed to be ineffective after long-term use[9] and is no longer regularly available. Tegaserod, a 5-hydroxytryptamine type 4 agonist, has shown to improve bowel movement frequency and stool consistency[26]. In addition, improvement in subjective experience of symptoms by PD patients has been observed[27]. Further trials are not expected since this drug was also withdrawn because of an increased risk of serious cardiovascular adverse events.

In patients with alarming signs of possible necrosis or perforation, immediate surgical intervention is needed. When symptoms are mild and not worrisome, urgent endoscopic detorsion should be considered as the first choice of treatment[16,25,28]. Endoscopy enables direct assessment of the viability of the colonic mucosa. Although endoscopic detorsion has high recurrence rates, varying from 3.3% to over 60%[29,30] , it is a relatively safe procedure with mortality rates of 1%-3%[29,31].

In cases of successful endoscopic detorsion, semi-elective sigmoidectomy can be performed. This allows an appropriate workup to achieve optimal preoperative conditions. Mortality rates vary between 0% and 10%[16,23,32,33].

In recurrent volvulus, surgery is the first choice of treatment as endoscopy in recurrent volvulus is accompanied by a raised mortality rate of up to 20%[16]. However, surgical treatment in the acute phase of volvulus is also known to have high mortality[16,17,23,29,31].

There are several surgical options to treat volvulus, ranging from operative detorsion alone to retroperitoneal fixation and partial resection with or without primary anastomosis. Detorsion alone has a very high recurrence rate of up to 74%[16,31].

Resection performed with primary anastomosis is advocated by some authors as it has the advantage of avoiding a second operation to restore continuity[25,28,32]. Mortality in this group ranges from 0%-19%[23,28,33]. If the expected surgical morbidity and mortality is unacceptably high or if patients refuse surgery, as in our case, PEC can be considered. Under endoscopic vision, a tube is placed percutaneously in the distal colon. This allows fixation of the colon to the abdominal wall and if necessary offers direct access for laxatives and desufflation. Complications following PEC such as infection, faecal leakage and buried internal bolster can cause significant morbidity, but is a good alternative in selected cases[34,35]. There are few available publications on recurrence rate after PEC[34,35].

In conclusion, gastrointestinal dysfunction is a common feature in elderly patients, and especially in those affected by PD. Patients with chronic constipation are more likely to develop a complication like sigmoid volvulus. The association between sigmoid volvulus and PD has been described previously. There are no data available suggesting different treatment for sigmoid volvulus in PD patients. In general, endoscopic detorsion can be performed as the first choice of treatment in acute sigmoid volvulus if signs of an acute abdomen are absent. This should be followed by resection at a later stage if the condition of the patient allows surgical intervention. However, if there are signs of gangrene, an emergency operation is the only therapeutic option and endoscopic treatment should not delay surgery. PEC is an alternative treatment for selected cases if surgical intervention is not an option.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Dr. Ali Harlak, Department of General Surgery, Gulhane Military Medical Academy, GATA Genel Cerrahi AD, 06018 Ankara, Turkey

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.Edwards LL, Pfeiffer RF, Quigley EM, Hofman R, Balluff M. Gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1991;6:151–156. doi: 10.1002/mds.870060211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siddiqui MF, Rast S, Lynn MJ, Auchus AP, Pfeiffer RF. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: a comprehensive symptom survey. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;8:277–284. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(01)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards LL, Quigley EM, Harned RK, Hofman R, Pfeiffer RF. Characterization of swallowing and defecation in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards LL, Quigley EM, Pfeiffer RF. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: frequency and pathophysiology. Neurology. 1992;42:726–732. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakakibara R, Shinotoh H, Uchiyama T, Sakuma M, Kashiwado M, Yoshiyama M, Hattori T. Questionnaire-based assessment of pelvic organ dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Auton Neurosci. 2001;92:76–85. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, White LR, Masaki KH, Tanner CM, Curb JD, Grandinetti A, Blanchette PL, Popper JS, Ross GW. Frequency of bowel movements and the future risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57:456–462. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savica R, Rocca WA, Ahlskog JE. When does Parkinson disease start? Arch Neurol. 2010;67:798–801. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwab RS, England AC. Parkinson’s disease. J Chronic Dis. 1958;8:488–509. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(58)90006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jost WH. Gastrointestinal motility problems in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Effects of antiparkinsonian treatment and guidelines for management. Drugs Aging. 1997;10:249–258. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199710040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakakibara R, Odaka T, Uchiyama T, Asahina M, Yamaguchi K, Yamaguchi T, Yamanishi T, Hattori T. Colonic transit time and rectoanal videomanometry in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:268–272. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jost WH, Schimrigk K. Constipation in Parkinson’s disease. Klin Wochenschr. 1991;69:906–909. doi: 10.1007/BF01798536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singaram C, Ashraf W, Gaumnitz EA, Torbey C, Sengupta A, Pfeiffer R, Quigley EM. Dopaminergic defect of enteric nervous system in Parkinson‘s disease patients with chronic constipation. Lancet. 1995;346:861–864. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kupsky WJ, Grimes MM, Sweeting J, Bertsch R, Cote LJ. Parkinson’s disease and megacolon: concentric hyaline inclusions (Lewy bodies) in enteric ganglion cells. Neurology. 1987;37:1253–1255. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.7.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caplan LH, Jacobson HG, Rubinstein BM, Rotman MZ. Megacolon and volvulus in parkinson’s disease. Radiology. 1965;85:73–79. doi: 10.1148/85.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewitan A, Nathanson L, Slade WR. Megacolon and dilatation of the small bowel in parkinsonism. Gastroenterology. 1951;17:367–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grossmann EM, Longo WE, Stratton MD, Virgo KS, Johnson FE. Sigmoid volvulus in Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:414–418. doi: 10.1007/BF02258311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dülger M, Cantürk NZ, Utkan NZ, Gonullu NN. Management of sigmoid colon volvulus. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1280–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avots-Avotins KV, Waugh DE. Colon volvulus and the geriatric patient. Surg Clin North Am. 1982;62:249–260. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)42684-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madiba TE, Thomson SR. The management of sigmoid volvulus. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2000;45:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenthal MJ, Marshall CE. Sigmoid volvulus in association with parkinsonism. Report of four cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:683–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb04346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delpre G, Kadish U, Wolloch Y. [Volvulus of the sigmoid colon and ischemic colitis in Parkinson’s disease: the same complication?] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14:286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handwerker J, Raptopoulos VD. A medical mystery: dilated bowel--the answer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1381–1382. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc076078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson JR, Lee D. The management of acute sigmoid volvulus. Br J Surg. 1981;68:117–120. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800680217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonnenberg A, Tsou VT, Müller AD. The „institutional colon“: a frequent colonic dysmotility in psychiatric and neurologic disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renzulli P, Maurer CA, Netzer P, Büchler MW. Preoperative colonoscopic derotation is beneficial in acute colonic volvulus. Dig Surg. 2002;19:223–229. doi: 10.1159/000064217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan JC, Sethi KD. Tegaserod in constipation associated with Parkinson disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2007;30:52–54. doi: 10.1097/01.WNF.0000240942.21499.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan KL, Staffetti JF, Hauser RA, Dunne PB, Zesiewicz TA. Tegaserod (Zelnorm) for the treatment of constipation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21:115–116. doi: 10.1002/mds.20666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sule AZ, Iya D, Obekpa PO, Ogbonna B, Momoh JT, Ugwu BT. One-stage procedure in the management of acute sigmoid volvulus. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1999;44:164–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oren D, Atamanalp SS, Aydinli B, Yildirgan MI, Başoğlu M, Polat KY, Onbaş O. An algorithm for the management of sigmoid colon volvulus and the safety of primary resection: experience with 827 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:489–497. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0821-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martínez Ares D, Yáñez López J, Souto Ruzo J, Vázquez Millán MA, González Conde B, Suárez López F, Alonso Aguirre P, Vázquez Iglesias JL. Indication and results of endoscopic management of sigmoid volvulus. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2003;95:544–548, 544-548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutcliffe MM. Volvulus of the sigmoid colon. Br J Surg. 1968;55:903–910. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800551207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lau KC, Miller BJ, Schache DJ, Cohen JR. A study of large-bowel volvulus in urban Australia. Can J Surg. 2006;49:203–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turan M, Sen M, Karadayi K, Koyuncu A, Topcu O, Yildirir C, Duman M. Our sigmoid colon volvulus experience and benefits of colonoscope in detortion process. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2004;96:32–35. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082004000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowlam S, Watson C, Elltringham M, Bain I, Barrett P, Green S, Yiannakou Y. Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy of the left side of the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baraza W, Brown S, McAlindon M, Hurlstone P. Prospective analysis of percutaneous endoscopic colostomy at a tertiary referral centre. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1415–1420. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]