Abstract

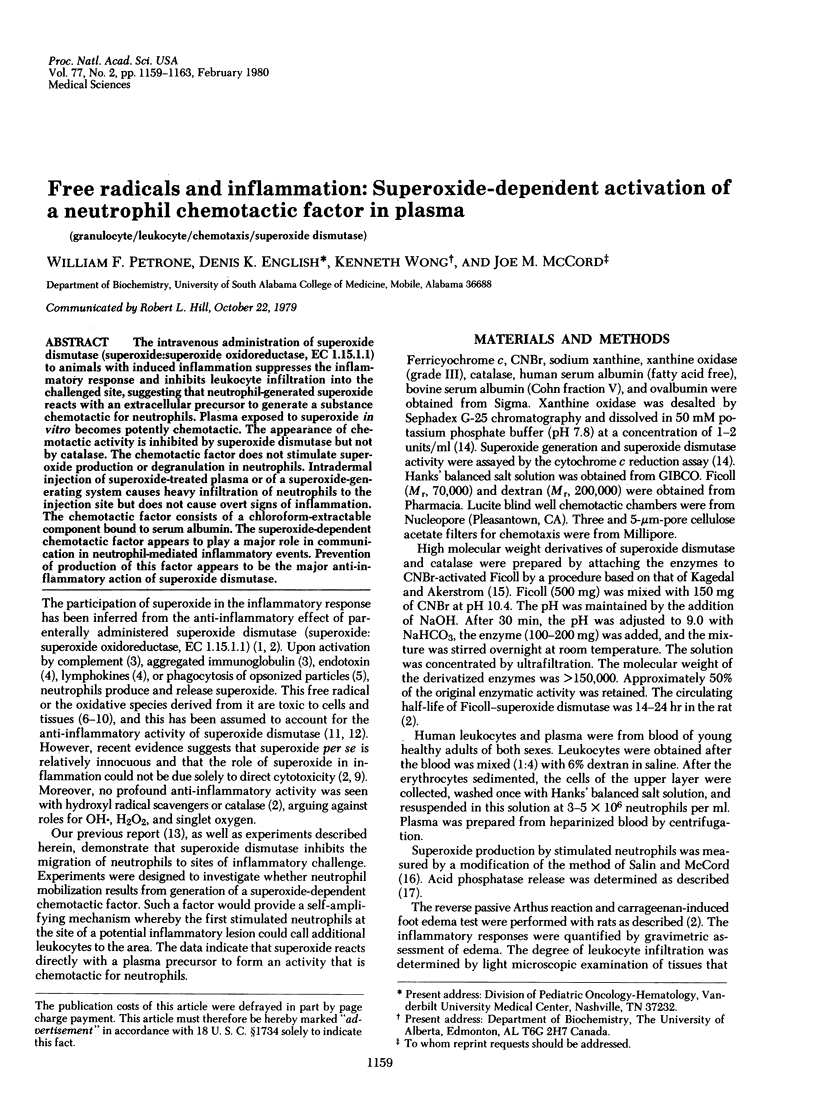

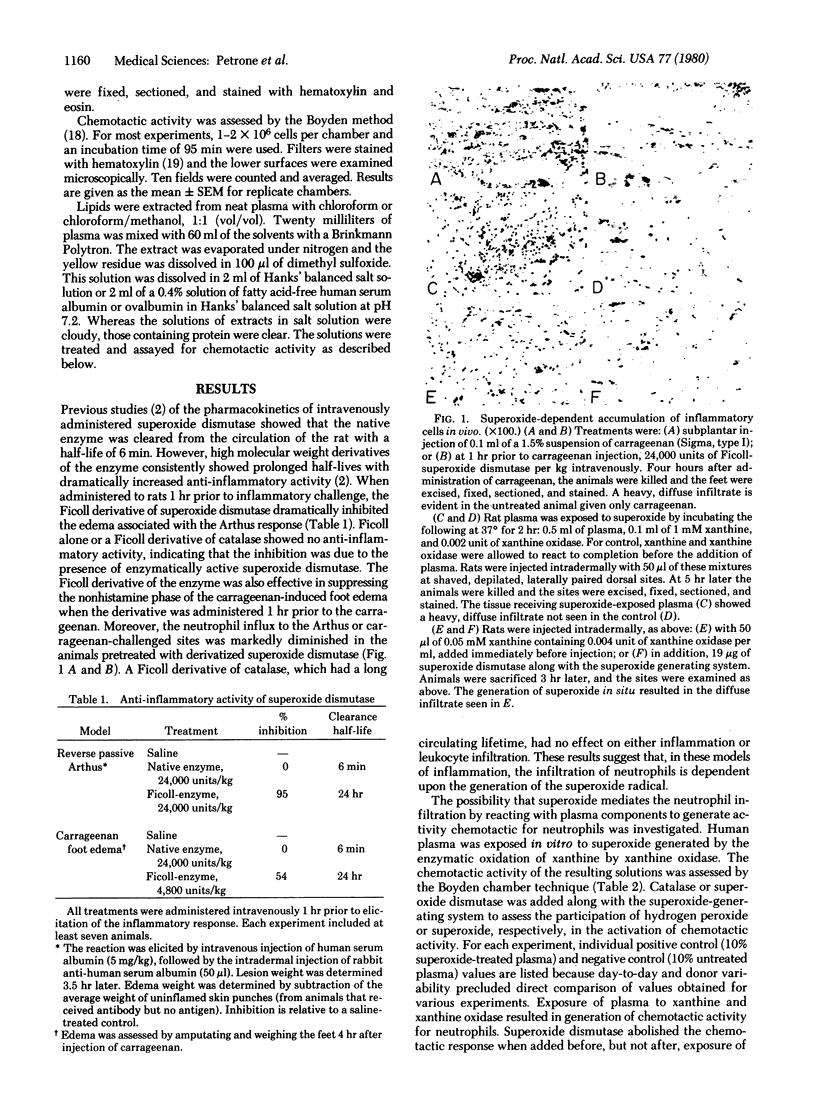

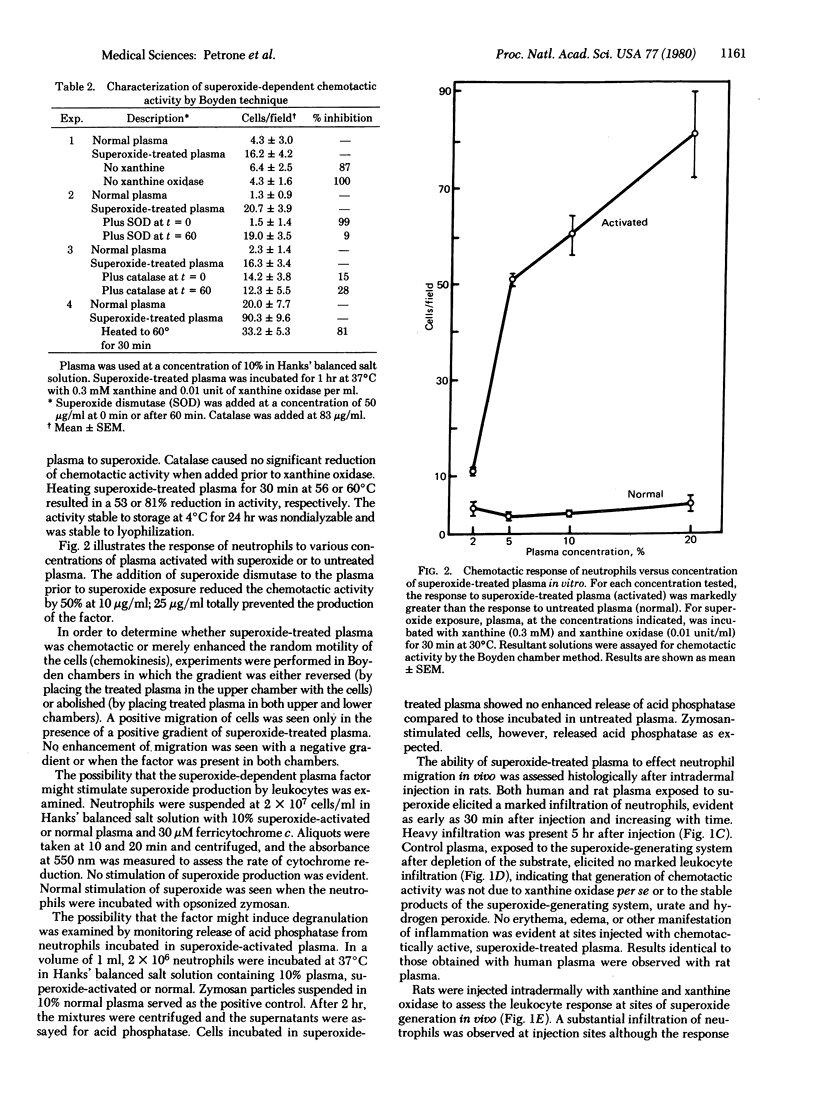

The intravenous administration of superoxide dismutase (superoxide:superoxide oxidoreductase, EC 1.15.1.1) to animals with induced inflammation suppresses the inflammatory response and inhibits leukocyte infiltration into the challenged site, suggesting that neutrophil-generated superoxide reacts with an extracellular precursor to generate a substance chemotactic for neutrophils. Plasma exposed to superoxide in vitro becomes potently chemotactic. The appearance of chemotactic activity is inhibited by superoxide dismutase but not by catalase. The chemotactic factor does not stimulate superoxide production or degranulation in neurtrophils. Intradermal injection of superoxide-treated plasma or of a superoxide-generating system causes heavy infiltration of neutrophils to the injection site but does not cause overt signs of inflammation. The chemotactic factor consists of a chloroform-extractable component bound to serum albumin. The superoxide-dependent chemotactic factor appears to play a major role in communication in neutrophil-mediated inflammatory events. Prevention of production of this factor appears to be the major anti-inflammatory action of superoxide dismutase.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BOYDEN S. The chemotactic effect of mixtures of antibody and antigen on polymorphonuclear leucocytes. J Exp Med. 1962 Mar 1;115:453–466. doi: 10.1084/jem.115.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M., Curnutte J. T., Kipnes R. S. Biological defense mechanisms. Evidence for the participation of superoxide in bacterial killing by xanthine oxidase. J Lab Clin Med. 1975 Feb;85(2):235–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M., Kipnes R. S., Curnutte J. T. Biological defense mechanisms. The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J Clin Invest. 1973 Mar;52(3):741–744. doi: 10.1172/JCI107236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Perez J. L., Goldyne M. E., Winkelmann R. K. Prostaglandins and chemotaxis: enhancement of polymorphonuclear leukocyte chemotaxis by prostaglandin F2alpha. J Invest Dermatol. 1976 Mar;66(3):149–152. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12481893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl E. J., Gorman R. R. Chemotactic and chemokinetic stimulation of human eosinophil and neutrophil polymorphonuclear leukocytes by 12-L-hydroxy-5,8,10-heptadecatrienoic acid (HHT). J Immunol. 1978 Feb;120(2):526–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl E. J., Woods J. M., Gorman R. R. Stimulation of human eosinophil and neutrophil polymorphonuclear leukocyte chemotaxis and random migration by 12-L-hydroxy-5,8,10,14-eicosatetraenoic acid. J Clin Invest. 1977 Jan;59(1):179–183. doi: 10.1172/JCI108617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein I. M., Roos D., Kaplan H. B., Weissmann G. Complement and immunoglobulins stimulate superoxide production by human leukocytes independently of phagocytosis. J Clin Invest. 1975 Nov;56(5):1155–1163. doi: 10.1172/JCI108191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kågedal L., Akerström S. Binding of covalent proteins to polysaccharides by cyanogen bromide and organic cyanates. I. Preparation of soluble glycine-, insulin- and ampicillin-dextran. Acta Chem Scand. 1971;25(5):1855–1859. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.25-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle F., Michelson A. M., Dimitrijevic L. Biological protection by superoxide dismutase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973 Nov 16;55(2):350–357. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)91094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M. Free radicals and inflammation: protection of synovial fluid by superoxide dismutase. Science. 1974 Aug 9;185(4150):529–531. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4150.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M., Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J Biol Chem. 1969 Nov 25;244(22):6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M., Fridovich I. The biology and pathology of oxygen radicals. Ann Intern Med. 1978 Jul;89(1):122–127. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-1-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson A. M., Buckingham M. E. Effects of superoxide radicals on myoblast growth and differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974 Jun 18;58(4):1079–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(74)80254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra H., Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase and the oxygen enhancement of radiation lethality. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1976 Oct;176(2):577–581. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S., Lynn W. S. Lipid chemotaxins isolated from culture filtrates of Escherichia coli and from oxidized lipids. Inflammation. 1977 Mar;2(1):47–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00920874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin M. L., McCord J. M. Free radicals and inflammation. Protection of phagocytosine leukocytes by superoxide dismutase. J Clin Invest. 1975 Nov;56(5):1319–1323. doi: 10.1172/JCI108208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin M. L., McCord J. M. Superoxide dismutases in polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Clin Invest. 1974 Oct;54(4):1005–1009. doi: 10.1172/JCI107816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. W., Hollers J. C., Patrick R. A., Hassett C. Motility and adhesiveness in human neutrophils. Effects of chemotactic factors. J Clin Invest. 1979 Feb;63(2):221–229. doi: 10.1172/JCI109293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. J., Mehl K. S., Pryor W. A. The role of the superoxide anion in the xanthine oxidase-induced autoxidation of linoleic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978 Aug 14;83(3):927–932. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner S. R., Campbell J. A., Lynn W. S. Polymorphonulcear leukocyte chemotaxis toward oxidized lipid components of cell membranes. J Exp Med. 1975 Jun 1;141(6):1437–1441. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.6.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaes G. On the mechanisms of bone resorption. The action of parathyroid hormone on the excretion and synthesis of lysosomal enzymes and on the extracellular release of acid by bone cells. J Cell Biol. 1968 Dec;39(3):676–697. doi: 10.1083/jcb.39.3.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Albumin and "total globulin" fractions of blood. Adv Clin Chem. 1965;8:237–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]