Abstract

Background & Aims: This study was performed to improve the autofluorescence imaging (AFI) in the upper GI tract by applying a new method of normalized autofluorescence (NAFI) obtained via tri-modal imaging. Objective: NAFI may provide lower false positive rate to achieve ultimately better specificity at acceptable sensitivity. Patients and methods: This is a prospective, controlled single-centre study. 18 patients with suspected esophagus or stomach cancer undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were enrolled between February and May 2010. After endoscopy each patient was assigned into one of two groups: (1) non- cancer, including inflammation; (2) cancer group. EGDs were performed using video white light endoscopy, followed by AFI/NAFI. The targeted biopsy samples were taken from the abnormal areas as well as from adjacent mucosa. NAFI was compared versus AFI for cancer diagnostics in terms of specificity and sensitivity. Results: NAFI detected all neoplastic lesions. WLE or NBI detected no additional neoplasia. The AFI displayed mucosal inflammation and carcinomas of esophagus and stomach as dark red color, the normal mucosa background was displayed as light green. The NAFI didn’t differentiate inflamed tissue from normal in majority of cases, but in tumorous mucosa, the cancer areas were detected precisely. AFI shows 100% sensitivity but 50% specificity which correlates with previous literature data. On the other hand, NAFI demonstrated lower sensitivity (88%) but higher specificity compared to AFI (69%). Conclusions: Measuring the NAFI instead of the AFI was found improving the specificity of cancer diagnosis. Use of fiber-optic endoscopes to analyze AFI and possible endoscopic and histological sampling error are the main potential limitations of this method.

Keywords: Autofluorescence imaging, NAFI, endoscopic tri-modal imaging, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, cancer diagnostic

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) neoplasms continue to be one of the leading cancer-related deaths worldwide; therefore early detection of pre-cancerous stages in the upper GI tract is subject to extensive research efforts throughout the world. One of the highest shares in GI malignancies belongs to the upper GI including esophagus and stomach. Furthermore, presence of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) and chronic gastritis increase the risk of malignancy development [1,2].

BE is a known precursor for development of esophageal cancer, and is frequently linked to the pre-existing GERD [3,4]. Patients with BE have a 30-125 fold higher risk of developing cancer of the esophagus than the general population [5]. The early detection and treatment of oesophagus cancer can significantly improve patient survival. When detected early, the curative endoscopic resection may be an option, without the need for surgery [6,7]. Unfortunately, the poor detection of pre-cancer and early stage cancer in BE by WLE is a significant limitation [8].

The sensitivity and positive predictive value of standard EGD for diagnosing BE was reportedly 82% and 34% respectively [9]. The routine protocol of cancer detection at BE prescribes 4-quadrant biopsies taken at regular intervals throughout the BE, and even the most rigorous biopsy protocols may be associated with sampling error [10]. The detection of gastric cancer in different studies showed a sensitivity of 84.2-92% and a specificity of 78-89.7% [7,11-14].

Despite the progressive development of endoscopic modalities, the early detection of superficial neoplasms during routine EGD remains difficult because there are few morphological changes that differentiate malignant from nonmalignant lesions [1]. Accurate diagnosis of tumor extent delineation is sometimes difficult because gastric neoplasms occasionally have flat or isochromatic tumor extensions.

To date, a clinical demand is still high for screening methods to highlight especially early lesions. Such methods as Optical Coherence Tomography [15,16], Laser Scattering Spectroscopy [17], Raman Spectroscopy [18], Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy [19], Chromoendoscopy [20,21], Magnification Chromoendoscopy [22], Infrared Endoscopy [23] and Spectral Imaging, particularly Fluorescence Imaging including Autofluorescence Imaging (AFI) [24,25] and Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) [26] have been successfully applied in the GI tract including esophagus and stomach, for biopsy guidance and microsurgery navigation[27-31]. Recently, WLE, AFI and NBI have been incorporated into one system: endoscopic tri-modal imaging [32,33].

AFI endoscopy imaging produces real-time pseudo-color images based on natural tissue. Autofluorescence (AF) emitted by light excitation from endogenous fluorophores such as collagen, elastin, nicotinamide, adenine dinucleotide (NADH), flavins (FAD) and porphyrins [34,35]. This method is able to identify lesions, including malignancies, by detecting differences in tissue fluorescence, thus revealing early carcinomas, not yet detectable by conventional WLE. Because of these properties AFI may potentially improve the identification and characterization of the premalignant lesions in oesophageal and gastric mucosa [35,36]. Despite the reported success for AFI in the respiratory tract and lower GI tract, these approaches are still not specific enough to discover dysplastic or cancer lesions in the esophagus with intestinal metaplastic background [25,37] or flat lesions in the stomach where specificity for AFI varied from author to author from 21% to 69 % (for BE) to 92% (for stomach) [38].

One of the contemporary approaches to improve the specificity and image quality of the AFI diagnostics is to measure an intrinsic AF, the parameter decoupled from the excitation and emission absorption and scattering by biological tissues, as opposed to the state of the art AF technique where the AF is measured as a product of the intrinsic AF, and emission reabsorption and scattering, i.e. so-called measured AF [39,40]. Collecting the intrinsic AF instead of measured by means of the spectroscopy was found enhancing the specificity of cancer diagnostics although the improvement of the sensitivity was found insignificant or even reduced.

The AF is a product of emission re-absorption and intrinsic fluorescence; if the measured AF is normalized over the diffuse reflectance and taking into account the difference between the path lengths of the diffusively reflected and fluoresced photons, one can obtain the intrinsic AF. Receiving a true intrinsic AF image will require spectrally resolved imaging dataset such as hyperspectral imaging collection. Hence, we normalized the green RGB channel of AFI over either the blue or green channels of WLI, or green or blue channels of NBI to finally obtain 4 normalized AF images (NAFI).

The working hypothesis of this study is that such innovation as NAFI may provide lower false positive rate to achieve ultimately better specificity at acceptable sensitivity.

Materials and methods

Patient criteria

Prospectively, 18 patients (12 male, 6 female; median age 63.3 years, age range 51-73 years) undergoing EGD during the period between February and May 2010, were enrolled. The first 6 patients (2 with esophageal adenocarcinoma, 1 with gastric adenocarcinoma, 2 with GERD, 1 with BE with dysplasia) were considered as a pilot group. The pilot data were used to finalize the data collection and data analysis protocols for NAFI and were not included into the final clinical data analysis.

12 patients were examined using both the new technique NAFI and state of the art technique AFI: 2 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, 3 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma, 2 patients with GERD, 2 patients with BE with dysplasia, and 3 patients with normal results of EGD, who were undergoing surveillance procedure because of suspected cancer.

The indications for EGD were as following: suspected or known esophagus or stomach cancer, BE; complains suspicious for acute or chronic gastritis or esophagitis. The diagnoses were made by correlation of patient’s medical history, endoscopy, and histological results of targeted biopsy specimens, taken from suspicious areas. The Montreal classification was used for definition of BE; Los-Angeles classification was used for the diagnosis of GERD [41-43].

The following exclusion criteria were applied: Age < 18 years; unable or unwilling to give informed consent. Further, ionizing radiation therapy to the chest or abdomen within the past six months; chromoendoscopy within the past 7 days; significant upper GI bleeding of any etiology; esophageal candidiasis; chemotherapy for cancer within three months; confocal laser endoscopy with fluorescent photosensitizing drugs within two months.

A signed informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study. The study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the University Erlangen-Nuremberg. During the examination the patients received upon requirement sedation with Midazolam and Pethidin.

Endoscopic procedure

EGDs were performed using WLE followed by AFI endoscopy, using conventional fiber-optic gastroscope (GIF H180) with fluorescence endoscopy system (PinPoint™, Novadaq, Canada) described below in Data collection section [44].

Each endoscopy was performed by two experienced endoscopists in a single-center setting and all endoscopic findings for each lesion were mutually agreed upon. After obtaining the image set, biopsy samples were taken from the lesion, as well as from normal adjacent mucosa. The biopsy specimens were evaluated by two pathologists, blinded to the results of AFI and NAFI endoscopy, one of them considered as a gastrointestinal expert. Biopsies were classified according to the Vienna criteria of GI epithelial neoplasia [14]. In case of disagreement between the pathologists, discussion led to a consensus diagnosis. Low-grade and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, as well as invasive neoplasia was defined as neoplasia; lesions diagnosed as indefinite for neoplasia were not considered neoplastic.

The main limitation of our study was that our AFI endoscopy system was applicable only to fiber-optic endoscopes, facilitating reduced spatial resolution as compared to video-endoscopy. Further, the endoscopists were aware of the clinical history of the patients and may have detected the suspicious lesions with WLE that would have been inconspicuous without such awareness. The possibility that certain areas were endoscopically mismatched (endoscopic sampling error) or wrongly sampled (histological sampling error) also can’t be completely excluded, although all lesions and biopsies were carefully documented during the procedure by an assistant on a specially designed scoring sheet.

Data collection

The PINPOINT™ system (Novadaq Technologies Corp, ON, Canada, former Onco-LIFE™, Xillix Technologies Corp, Canada) comprises a switchable light source and dual-camera unit (one 3-color chip CCD and one monochrome ICCD). Illumination for both WLE and fluorescence endoscopy is provided by a super high-brightness mercury lamp (VIP R 150/P24, Osram, Germany). In fluorescence mode, the green portion of the light source emission is suppressed by an optical notch filter, so that the output is a combination of the remaining blue and red light (purple). The excitation purple light is coupled to a fiberoptic endoscope that projects it onto the tissue and collects the fluorescence (green) and diffuse reflectance (red) light.

Normal tissue is displayed as cyan or green, while abnormal tissue is shown as a range of red color, depending on the red-to-green ratio [45]. The shadows consequently displayed as dim or no signal dark patches. The central 16 x 12 pixels are averaged over 4 frames and continuously displayed on the fluorescence image as a numerical color value (NCV). The higher the NCV the lower the fluorescence intensity (associated with neoplasia): hence high NCVs (the threshold was set as NCV>0.9) help confirm the abnormality of lesions seen on the fluorescence image.

The image set was acquired in burst “one by one” mode; each set containing 3 still images of WLE, AFI and NBI of the same tissue spot taken from the same distance and angle, i.e. keeping the measurement geometry constant. Monitoring, triggering and capturing of the video frames was provided using original software created in Matlab (R2007b, Mathworks Inc., USA). Images of 768 x 576 pixel resolution were obtained from the digital video footage, in TIFF format. The manual switching between conventional and fluorescence modes was carried out by the foot pedal.

Image processing

During endoscopy three types of images were taken - WLE, AFI and NBI. The colors of each of these images are encoded via red (R), green (G) and blue (B) channels. Images contained an illuminated circular area of interest (AOI). The approximate radius and coordinates of the center of the AOI within the images were estimated using a rudimentary level approach, i.e. we averaged over all channels of WLE, AFI and NBI which generated a grey-scale image per channel.

We looked at a variety of fractions between individual channels in the AOI. The nonlinear scaling essentially allows inspecting detail that the human eye would not be able to differentiate in the almost unicolor dark images of unscaled pixel wise fractions F.

For the purpose of specifying what looks like cancer to an experienced endoscopist, contours were drawn manually into endoscopic images and grey scale images of NAFI. Then we counted the pixels circumferenced by the contours drawn by the endoscopist in a given image. We considered the lesion identified correctly by NAFI, if within the lesion margins its grey grade intensity differs by more than 10% as opposed to the adjacent tissue (according to the contrast sensitivity of the human eye) and this gradient is represented by more than 10% of the pixels within the observation spot or AOI. This evaluation has been carried out based on a pixel by pixel sensitivity. The sensitivity and specificity preliminary analysis of this study has been performed on patient by patient or image by image (in case we had more than one image per patient) basis using the 10% rule described above as the cancer identification threshold for a given tissue observation AOI.

Results

After normalization of AF, in a per patient analysis, we evaluated images of 12 patients in total: 2 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, 2 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma, 1 patient with acute ulcerated gastritis, 2 patients with GERD, 2 patients with BE with dysplasia, and 3 patients with normal results of EGD.

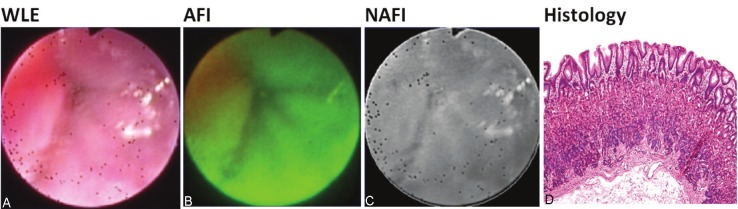

In general, mucosal inflammation and carcinomas of esophagus and stomach appeared as similar shade dark red color on the AFI images, the normal mucosa background was displayed as cyan or light green (Figure 1A-C). We did not evaluate shades of green color with regard to chronic inflammation in this study, as this work was done by other groups [36]. NAFI images were displayed in scale of grey. Image sets representative of those made during the examination are shown in Figures 2, 3 and 4.

Figure 1.

A-D: Appearance of normal gastric mucosa in WLE, AFI, NAFI and histology.

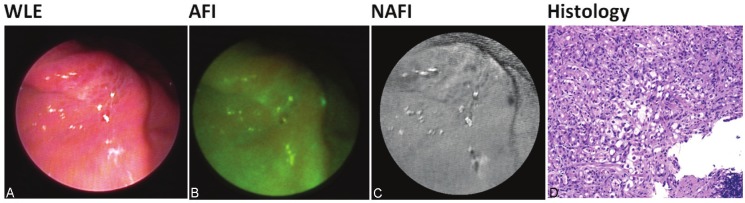

Figure 2.

A-D: Patient with gastric signet ring cell carcinoma. Both AFI and NAFI detected the cancer. Histologicalexamination revealed signet ring cell carcinoma (D).

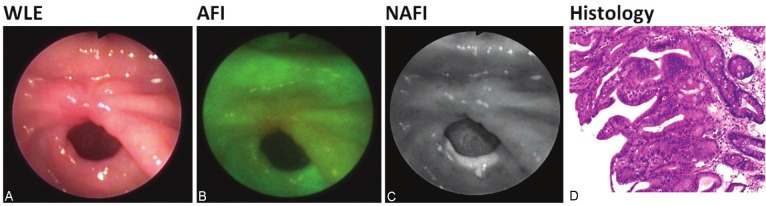

Figure 3.

A-D: Patient with gastric adenocarcinoma removed in early stage using ESD technique 2 months prior tothis surveillance EGD. Macroscopically, the pyloric mucosa at the site of the previously excised early gastric cancershowed redness with a prominent edematous pit pattern. WLE shows a red spot at the site of prior cancer. AFIhighlighted a wider area. NAFI displayed a much smaller spot as compared to WLE, but suspected neoplasia. Histologicalexamination showed villous glandular architecture with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia with interveningintestinal metaplasia.

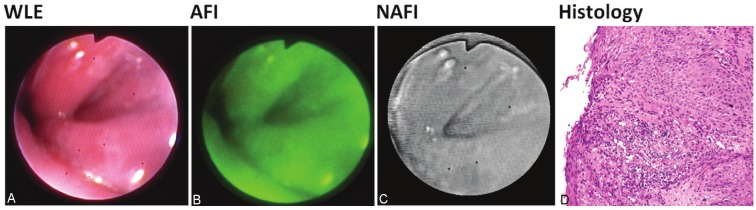

Figure 4.

A-D: Patient with reflux esophagitis; Grade C (LA Classification). Inflammation area can be observed aroundZ-line. WLE and AFI both displayed tongue-shaped patchy inflammation. NAFI recognized the area of inflammationin WLE again as a normal tissue. Histological examination showed superficial erosion with prominent acanthosis ofthe adjacent mucosa consistent with erosive esophagitis.

In case of mucosal inflammation, AFI shows wide patchy redness and rarely displays it precisely. NAFI doesn’t differentiate inflamed tissue from normal in majority of cases. In tumorous mucosa, shown by AFI, NAFI in most cases displays the cancer area more accurately, which was confirmed by histological results of biopsy specimens. However, the quantitative pixel by pixel comparative analysis of NAFI versus AFI diagnostics is not considered in this paper. In terms of precision of tumor recognition by NAFI, there was no significant difference between esophagus and stomach cancer.

In both patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus we could identify the presence of carcinoma using WLE. AFI showed normal mucosa as light green shade and cancerous tissue as dark red in both cases. In case the adjacent to cancer mucosa displayed on WLE inflammation signs, AFI showed it as a similar dark red shade. NAFI delineated tumor borders very precisely in one case and recognized beginning of the cancerous area as a normal tissue using WLE in another patient (Figure 2A-C). Histological examination revealed in both cases focal replacement of the normal squamous epithelial cells by atypical crowded squamous epithelial cells that have lost normal polarity and layering extending to the most superficial cell layer indicating high-grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasia associated with invasive moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 2D).

Two further patients exhibited gastric adenocarcinoma. In one case the tumor could be identified very easily using WLE; the results were confirmed both by AFI and NAFI (Figure 2A-C). Histological examination revealed diffuse infiltration of the lamina propria mucosae by large polygonal cells filled with intracytoplasmic mucin and having atypical eccentric nuclei. These atypical cells stained strongly positive with the Periodic Schiff (PAS) and Alcian blue stain consistent with signet ring cell carcinoma (Figure 2D).

The next patient (Figure 3A-D) came to the surveillance EGD after the early gastric adenocarcinoma was removed using endoscopic submucosa dissection technique 2 months prior to this examination. WLE and AFI recognized big reddish spot where the tumor was removed. In contrast, NAFI displayed a spot, much smaller. Histological examination of the area identified by NAFI showed villous architecture of the glands with elongated hyperchromatic atypical stratified nuclei indicating low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia with intervening islands of intestinal metaplasia. The histology of biopsy specimens, taken from the area, delineated by AFI only showed normal mucosa, without any signs of malignancy.

The WLE suspected gastric ulcer in one patient, was not recognized by AFI. However, NAFI contoured ulcers precisely, but recognized them as a cancer. Histological examination showed fragments of florid peptic ulceration. The intact mucosa exhibited villous architecture and replacement of the foveolar epithelial cells and the mucous glands by mature goblet cells indicating intestinal metaplasia. There was no evidence of intraepithelial neoplasia or invasive cancer.

In one patient with erosive reflux esophagitis, AFI showed inflammation as patchy redness; in contrast to it, NAFI recognized in this and in general, the inflamed tissue as normal (Figure 4A-C). Histological examination showed focal superficial epithelial loss covered by fibrinous exsudate containing granulocytes. The adjacent mucosa displayed prominent acanthosis of the squamous epithelium with elongated rete pegs (Figure 4D).

The ROC analyses and statistical classification were performed for control (inflammation plus normal) vs. cancer group, based on per patient/AOI analysis. The results are summarized in Table 1 and show 100% sensitivity but 50% specificity for AFI which correlates with previous literature data of high false positive outcome. NAFI demonstrated lower sensitivity (88%) but higher specificity compare to AFI (69%).

Table 1.

Sensitivity and specificity data of both AFI and NAFI methods

| TN | TP | FN | FP | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFI | 11 | 7 | 0 | 11 | 100 % | 50 % |

| NAFI | 11 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 88 % | 69 % |

AFI shows 100% sensitivity but 50% specificity which correlates with previous literature data of high false positive outcome of AFI. NAFI demonstrated lower sensitivity (88%) but higher specificity compare to AFI (69%). AFI, Autofluorescence imaging; NAFI, normalized autofluorescence imaging.

Discussion

In our present study, we examined a new technique (NAFI), which was developed by normalizing the green imaging RGB channel of AFI over the green channel of the white light. We have evidence that the NAFI technique more precisely detects neoplasia as shown by the increased specificity compared to AFI.

With regard to specificity, some recent studies on AFI showed different results. Ohkawa et al investigated 109 gastric lesions using AFI, where all of 56 neoplastic lesions and 87.5% of adenomas were recognized as having abnormal AF images [46]. Aida et al investigated the clinicopathological features of early gastric carcinoma to improve the efficacy of endoscopic screening for the detection and showed 87.2% of the detection rate for WLE. The study showed specificity of 49.1% and sensitivity of 96.4% for the AFI technique. Asaoka et al compared WLE and AFI in screening for BE, and found that BE can be easily distinguished from normal mucosa on AFI by gray color vs. green of normal tissue [47]. Kato et al described that gastric carcinomas of the elevated type were found to appear purple, although depressed type had green color [11].

These observations are consistent with our study, where AFI showed 50% specificity for cancer group and a sensitivity of 100%. However the specificity of NAFI was 69% implicating that NAFI increases specificity. In contrast, the results of sensitivity analysis displayed a lower sensitivity of NAFI compared to AFI (88% vs. 100%).

In future, the further development of NAFI could be useful as an adjunct for routine EGD, because it does not require a troublesome dye spraying procedure like in case of chromoendoscopy, can be facilitated in real time, and provides a considerable specificity improvement.

In conclusion, this report is the first to describe the new method of normalized AFI, which instead of the state of the art AFI was found improving the specificity of cancer diagnostics. The aim of this study was to assess the feasibility of using NAFI for the detection of neoplasia in upper GI tract in a single- center setting. The data of this study will be assessed in an upcoming prospective randomized study, establishing feasibility of NAFI in a setting of high-resolution video endoscopy, aiming to clarify the true diagnostic potential of this new method for the detection of GI tract cancer.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding of the Erlangen Graduate School in Advanced Optical Technologies (SAOT) by the German National Science Foundation (DFG) in the framework of the excellence initiative.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- AFI

Autofluorescence imaging

- AOI

area of interest

- BE

Barrett’s esophagus

- ETMI

Endoscopic tri-modal imaging

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- GI

gastrointestinal

- GERD

gastro-esophageal reflux disease

- NAFI

normalized autofluorescence imaging

- Video-WLE

video white light endoscopy

- WLE

white light endoscopy

- NBI

narrow band imaging

References

- 1.Uedo N, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Yamada T, Ogiyama H, Imanaka K, Sugimoto N, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Narahara H, Ishiguro S. A novel videoendoscopy system by using autofluorescence and reflectance imaging for diagnosis of esophagogastric cancers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correa P. Chronic gastritis as a cancer precursor. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1984;104:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skinner DB, Walther BC, Riddell RH, Schmidt H, Iascone C, DeMeester TR. Barrett’s esophagus. Comparison of benign and malignant cases. Ann Surg. 1983;198:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198310000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hameeteman W, Tytgat GN, Houthoff HJ, van den Tweel JG. Barrett’s esophagus: development of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1249–1256. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(89)80011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bytzer P, Christensen PB, Damkier P, Vinding K, Seersholm N. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and Barrett’s esophagus: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ang TL, Khor CJ, Gotoda T. Diagnosis and endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Singapore Med J. 2010;51:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tougeron D, Michel P. [Gastric tumors] . Rev Prat. 2010;60:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dacosta RS, Wilson BC, Marcon NE. Spectroscopy and fluorescence in esophageal diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:41–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eloubeidi MA, Provenzale D. Does this patient have Barrett’s esophagus? The utility of predicting Barrett’s esophagus at the index endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:937–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.990_m.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falk GW, Rice TW, Goldblum JR, Richter JE. Jumbo biopsy forceps protocol still misses unsuspected cancer in Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:170–176. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato M, Uedo N, Ishihara R, Kizu T, Chatani R, Inoue T, Masuda E, Tatsumi K, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Iishi H, Tomita Y, Tatsuta M. Analysis of the color patterns of early gastric cancer using an autofluorescence imaging video endoscopy system. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pohl J, Pech O, May A, Manner H, Ell C. Endoscopic resection of early esophageal and gastric neoplasias. Dig Dis. 2008;26:285–290. doi: 10.1159/000177010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato M, Kaise M, Yonezawa J, Goda K, Toyoizumi H, Yoshimura N, Yoshida Y, Kawamura M, Tajiri H. Trimodal imaging endoscopy may improve diagnostic accuracy of early gastric neoplasia: a feasibility study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Flejou JF, Geboes K, Hattori T, Hirota T, Itabashi M, Iwafuchi M, Iwashita A, Kim YI, Kirchner T, Klimpfinger M, Koike M, Lauwers GY, Lewin KJ, Oberhuber G, Offner F, Price AB, Rubio CA, Shimizu M, Shimoda T, Sipponen P, Solcia E, Stolte M, Watanabe H, Yamabe H. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251–255. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li XD, Boppart SA, Van Dam J, Mashimo H, Mutinga M, Drexler W, Klein M, Pitris C, Krinsky ML, Brezinski ME, Fujimoto JG. Optical coherence tomography: advanced technology for the endoscopic imaging of Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2000;32:921–930. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poneros JM, Brand S, Bouma BE, Tearney GJ, Compton CC, Nishioka NS. Diagnosis of specialized intestinal metaplasia by optical coherence tomography. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:7–12. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace MB, Perelman LT, Backman V, Crawford JM, Fitzmaurice M, Seiler M, Badizadegan K, Shields SJ, Itzkan I, Dasari RR, Van Dam J, Feld MS. Endoscopic detection of dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus using light-scattering spectroscopy. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:677–682. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.16511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfau PR, Sivak MV Jr. Endoscopic diagnostics. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:763–781. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiesslich R, Neurath MF. Endoscopic confocal imaging. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S58–60. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connor MJ, Sharma P. Chromoendoscopy and magnification endoscopy in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2003;13:269–277. doi: 10.1016/s1052-5157(03)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wo JM, Ray MB, Mayfield-Stokes S, Al-Sabbagh G, Gebrail F, Slone SP, Wilson MA. Comparison of methylene blue-directed biopsies and conventional biopsies in the detection of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a preliminary study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:294–301. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma P, Weston AP, Topalovski M, Cherian R, Bhattacharyya A, Sampliner RE. Magnification chromoendoscopy for the detection of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2003;52:24–27. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieber CA, Urayama S, Rahim N, Tu R, Saroufeem R, Reubner B, Demos SG. Multimodal near infrared spectral imaging as an exploratory tool for dysplastic esophageal lesion identification. Opt Express. 2006;14:2211–2219. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haringsma J, Tytgat GN. Fluorescence and autofluorescence. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;13:1–10. doi: 10.1053/bega.1999.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kara MA, Smits ME, Rosmolen WD, Bultje AC, Ten Kate FJ, Fockens P, Tytgat GN, Bergman JJ. A randomized crossover study comparing light-induced fluorescence endoscopy with standard videoendoscopy for the detection of early neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:671–678. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kara MA, Peters FP, Fockens P, ten Kate FJ, Bergman JJ. Endoscopic video-autofluorescence imaging followed by narrow band imaging for detecting early neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Early gastric cancer: endoscopy, laparoscopy and surgery. Asian J Surg. 2003;26:1–3. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aida K, Yoshikawa H, Mochizuki C, Mori A, Muto S, Fukuda T, Otsuki M. Clinicopathological features of gastric cancer detected by endoscopy as part of annual health checkup. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:632–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kadowaki S, Tanaka K, Toyoda H, Kosaka R, Imoto I, Hamada Y, Katsurahara M, Inoue H, Aoki M, Noda T, Yamada T, Takei Y, Katayama N. Ease of early gastric cancer demarcation recognition: a comparison of four magnifying endoscopy methods. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1625–1630. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otani A, Amano Y, Koshino K, Takahashi Y, Mishima Y, Imaoka H, Moriyama I, Ishimura N, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Is autofluorescence imaging endoscopy useful for determining the depth of invasion in gastric cancer? Digestion. 2010;81:96–103. doi: 10.1159/000252767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otsuka Y, Niwa Y, Ohmiya N, Ando N, Ohashi A, Hirooka Y, Goto H. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy in the diagnosis of early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2004;36:165–169. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Broek FJ, Fockens P, van Eeden S, Reitsma JB, Hardwick JC, Stokkers PC, Dekker E. Endoscopic tri-modal imaging for surveillance in ulcerative colitis: randomised comparison of high-resolution endoscopy and autofluorescence imaging for neoplasia detection; and evaluation of narrow-band imaging for classification of lesions. Gut. 2008;57:1083–1089. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.144097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curvers WL, Singh R, Song LM, Wolfsen HC, Ragunath K, Wang K, Wallace MB, Fockens P, Bergman JJ. Endoscopic tri-modal imaging for detection of early neoplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus: a multi-centre feasibility study using high-resolution endoscopy, autofluorescence imaging and narrow band imaging incorporated in one endoscopy system. Gut. 2008;57:167–172. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.134213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falk GW. Autofluorescence endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haringsma J, Tytgat GN, Yano H, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Ogihara T, Watanabe H, Sato N, Marcon N, Wilson BC, Cline RW. Autofluorescence endoscopy: feasibility of detection of GI neoplasms unapparent to white light endoscopy with an evolving technology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:642–650. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.114419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoue T, Uedo N, Ishihara R, Kawaguchi T, Kawada N, Chatani R, Kizu T, Tamai C, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Tomita Y, Toth E. Autofluorescence imaging videoendoscopy in the diagnosis of chronic atrophic fundal gastritis. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egger K, Werner M, Meining A, Ott R, Allescher HD, Hofler H, Classen M, Rosch T. Biopsy surveillance is still necessary in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus despite new endoscopic imaging techniques. Gut. 2003;52:18–23. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi M, Tajiri H, Seike E, Shitaya M, Tounou S, Mine M, Oba K. Detection of early gastric cancer by a real-time autofluorescence imaging system. Cancer Lett. 2001;165:155–159. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bard MP, Amelink A, Skurichina M, den Bakker M, Burgers SA, van Meerbeeck JP, Duin RP, Aerts JG, Hoogsteden HC, Sterenborg HJ. Improving the specificity of fluorescence bronchoscopy for the analysis of neoplastic lesions of the bronchial tree by combination with optical spectroscopy: preliminary communication. Lung Cancer. 2005;47:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ntziachristos V, Turner G, Dunham J, Windsor S, Soubret A, Ripoll J, Shih HA. Planar fluorescence imaging using normalized data. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:064007. doi: 10.1117/1.2136148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neumann H, Monkemuller K, Kandulski A, Malfertheiner P. Dyspepsia and IBS symptoms in patients with NERD, ERD and Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Dis. 2008;26:243–247. doi: 10.1159/000121354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. quiz 1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dent J. Endoscopic grading of reflux oesophagitis: the past, present and future. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:585–599. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Douplik A, Chen D, Akens MK, Zanati S, Cirocco M, Bassett N, Marcon NE, Fengler J, Wilson BC. Assessment of photobleaching during endoscopic autofluorescence imaging of the lower GI tract. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42:224–231. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Douplik A, Leong WL, Easson AM, Done S, Netchev G, Wilson BC. Feasibility study of autofluorescence mammary ductoscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14:044036. doi: 10.1117/1.3210773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohkawa A, Miwa H, Namihisa A, Kobayashi O, Nakaniwa N, Ohkusa T, Ogihara T, Sato N. Diagnostic performance of light-induced fluorescence endoscopy for gastric neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2004;36:515–521. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asaoka D, Nagahara A, Oguro M, Kurosawa A, Osada T, Kawabe M, Hojo M, Yoshizawa T, Otaka M, Ogihara T, Watanabe S. Utility of autofluorescence imaging videoendoscopy in screening for Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2009;41(Suppl 2):E113. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]